Screen Rant

Star trek voyager's chakotay native american controversy explained.

Star Trek: Voyager had good intentions by introducing a Native American character, but Commander Chakotay was flawed due to a consultant’s deception.

Star Trek: Voyager had good intentions by introducing a Native American character, but Commander Chakotay (Robert Beltran) was flawed due to a consultant’s deception. An important aspect of Star Trek 's legacy has always been its efforts to portray a diverse future, one where people of all races and creeds come together to form a better version of humanity. Star Trek: The Original Series featured the first interracial kiss on American television, while Star Trek: Discovery does tremendous work in its portrayal of gay and non-binary characters.

Star Trek: Voyager looked to continue that tradition of inclusivity by featuring the first Starfleet crew member of Native American descent. Beltran was ultimately cast in the role of Chakotay, a former Maquis operative who joined forces with Captain Kathryn Janeway (Kate Mulgrew) and her crew after they ended up stranded in the Delta Quadrant. Voyager 's producers' hearts were in the right place, but Chakotay ended up something of a failed character, partially due to an infamous conman who tainted the character's early development.

Related: Voyager Killed Off Its Most Interesting Character Too Soon

Voyager's Chakotay Native American Controversy Explained

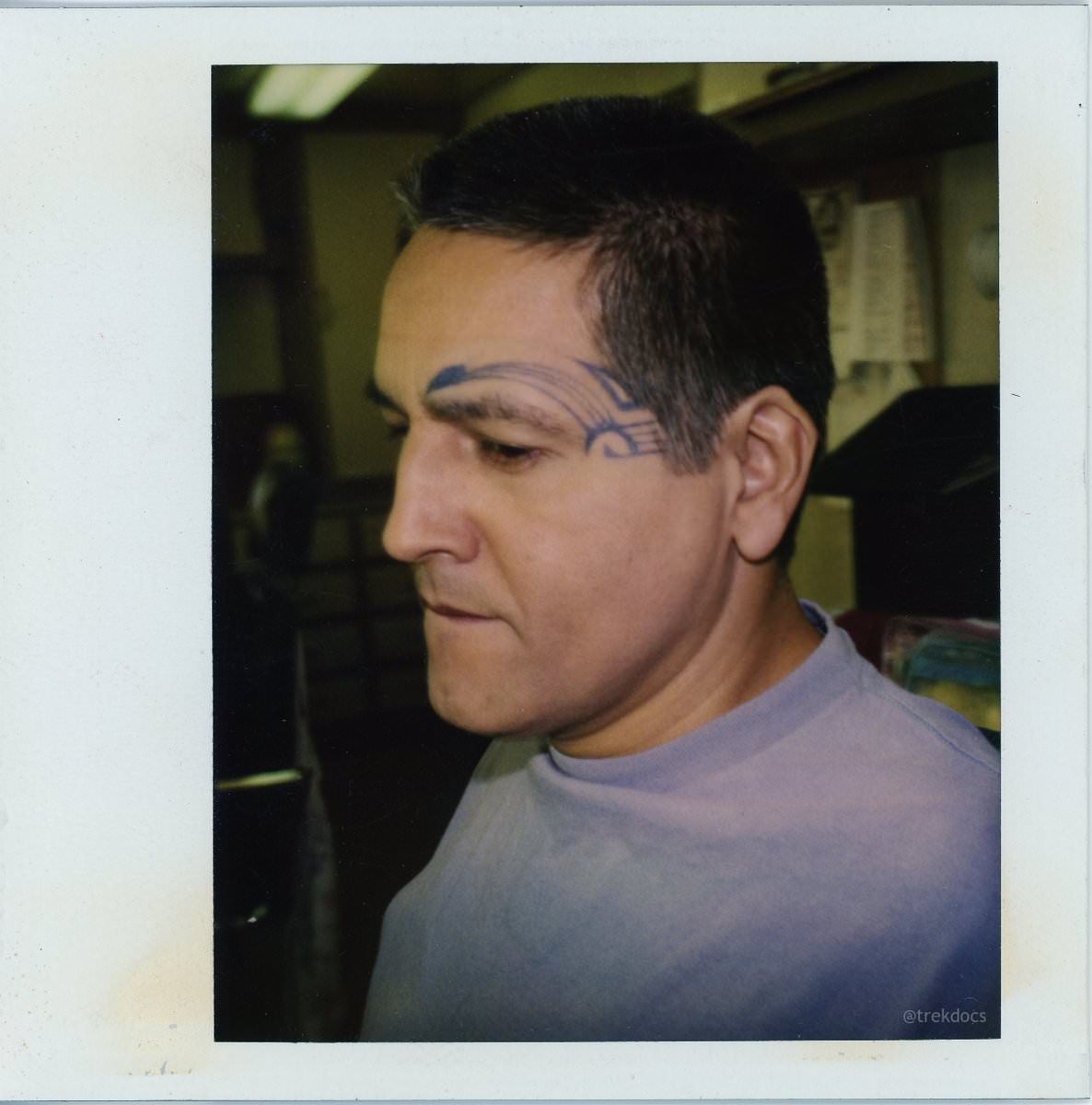

Star Trek: Voyager 's producers decided to make Chakotay's Native American background a key part of the character's personality. To get a better understanding of Native American heritage, the Voyager producers enlisted writer and journalist Jamake Highwater, a nationally recognized Native American authority who wrote books and produced TV series about his supposed heritage. Highwater was eventually exposed as a fraud; born Jackie Marks, he was of Eastern European descent and had no ties to the Cherokee people as he had long claimed.

Highwater's insights into the character proved to be shallow and stereotypical, hamstringing one of Star Trek: Voyager 's main characters before the show ever aired. Voyager 's producers seemed to realize Chakotay was not particularly working as a character, and he would slowly become a smaller presence on the series as the years went on. While it wasn't the only factor working against him, Highwater's contribution to Chakotay did real damage to the character.

Why Chakotay Was A Voyager Missed Opportunity

Chakotay stands as a serious missed opportunity for Star Trek: Voyager , and he was arguably the least compelling First Officer in all of Star Trek . Chakotay was in many ways the embodiment of Voyager 's overall problems, a bland character who felt like a poor copy of other, better Star Trek characters. There were opportunities to improve the character, such as introducing some tension between his Maquis refugees and the Voyager's largely Starfleet crew , but it never happened.

Robert Beltran was notoriously vocal about his misgivings with Voyager 's writing staff during the show's production, taking seemingly any opportunity to cut them down in the press and complain about the lack of character development for Chakotay. Beltran wasn't wrong, but his public comments likely had the opposite effect of what he intended, alienating the show's creative staff and leaving them less willing to develop Chakotay. Star Trek: Voyager had the right idea with Chakotay, but the execution was never quite there.

More: Voyager's Tuvok Was Almost TNG's Geordi

06 “A Cuchi Moya!” — Star Trek’s Native Americans

For decades, Science Fiction had offered those involved in a cultural phenomenon stigmatized as escapist entertainment the opportunity to playfully work through their visions of the future, exploring both scenarios they might hope for and those they were deeply afraid of. Against this background, it is not surprising that particularly people marginalized by the current social order use fantastic fictions to either unmask present socio-cultural practices as oppressive or to imagine alternative ways of living where they would be no longer disenfranchised.

The catchy Aliens and Others , title of Jenny Wolmark’s fine study of feminist Science Fiction, 1 points to the way in which the genre-specific trope of the alien has typically been employed as a projection space for the racial or sexual Other. The possibility SF thus offers to defamiliarize the heavily politicized positions of those who are racially, ethnically, or sexually “different” can entail liberatory as well as oppressive effects, as the genre can, on the one hand, provide fresh and new perspectives on discourses so overdetermined by history and politics, while it, on the other, allows a mainstream culture to displace and repress its own social guilt and responsibility.

Instead of examining the metaphorical association between aliens and Others or the ways in which minority authors have used the figure of the alien, I would like to address the representational practices of a decidedly mainstream SF “text”: Star Trek , the multi-media franchise born in 1965 as a short-lived television series ( Star Trek: The Original Series—TOS, 1965-69) which has grown to see three more televisual incarnations ( Star Trek: The Next Generation—STNG, 1987-94 ; Star Trek: Deep Space Nine—DS9 , 1993-99; and Star Trek: Voyager—VOY, since 1995) as well as nine feature films, numerous novels, computer games, etc. Star Trek particularly invites an investigation of its representations of “aliens and Others” for two reasons: first, the show is tremendously popular. According to a 1991 survey, 53% of all Americans classify themselves as Star Trek fans. 2 A search of the World Wide Web on a random day produced 376,512 sites related to Star Trek , the Helsinki-based page “Women of Star Trek” or the “Church of Shatnerology.”

The Star Trek shows can be seen virtually all around the globe, in countries ranging from the Czech Republic to South Africa or Indonesia. This popularity evidences that Star Trek speaks to the sensibilities of a considerable portion of (not only) the American public and routinely exposes many people to its narrations. The second reason why Star Trek particularly proposes itself for the kind of interrogation I am about to engage in lies in the fact that the program has always marketed itself as multicultural. The show has, since its inception in the mid 1960s, presented itself to its audiences as a Science Fiction program that explicitly sets out to compose a future in which people of all races, species and genders live together harmoniously. Gene Roddenberry, the man who created Star Trek , cast himself in the role of a visionary whose quotable insights into the destiny of the human “race” became the core of the program’s market identity. Among such often quoted soundbites were, for example:

Intolerance in the 23rd century? Improbable! If man survives that long, he will have learned to take a delight in the essential differences between men and between cultures, 3

Diversity contains as many treasures as those waiting for us on other worlds. We will find it impossible to fear diversity and to enter the future at the same time. 4

Star Trek’s effort to construct for itself a multicultural image can be traced to primarily two strategies. First, the program has been striving for a diverse cast of characters, from TOS ’ featuring a Black woman and an Asian man among its bridge crew, to DS9 and VOY showcasing an African American (male) and a (White) female in their respective Captain’s seats. The second strategy lies in the kinds of stories Star Trek chooses to tell. With reliable regularity, the program features self-conscious “issue”-episodes that are obviously designed to tell a parable on current political issues. These episodes follow a typical pattern in projecting real-life racial (or other) issues onto alien species. In “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”, the crew of the Enterprise encounter the humanoid alien Lokai, whose face is half black and half white, and who is apparently on the run in a stolen shuttlecraft. Soon, a law enforcement officer, Bele, comes hunting after Lokai. The two look exactly alike, only Lokai is white on the right side of his body and black on the left, while Bele’s colors are distributed the other way around. When Lokai urgently pleads with the Enterprise-crew to grant him political asylum, they learn that the aliens’ planet is riven by a deadly race-war, a war which, by the episode’s end, will have killed all life on the planet. When confronted with the madness of an ultimately genocidal hatred, the crew of the Enterprise tries to make sense of it by putting the conflict in the context of their own (human) history:

Chekov: There was persecution on earth once. I remember reading about it in my history class. Sulu: Yes, but it happened way back in the 20th century. There is no such primitive thinking today.

The episode is thus able to address the late 1960s’ reality of brutal race riots in a safe and unthreatening context. It simplifies the complex structure of race relations by locating the source of all tensions in each race’s dislike of the other’s physical appearance, a difference the episode seemingly strives to make as superficial and ludicrous as possible. The dialogue between Chekov and Sulu then affirms that humanity has long overcome this state of racial prejudice, thus casting themselves in a role of enlightened superiority. In striking similarity to the (ideo-)logic of the colonial encounter, the crew of the Enterprise attempt to educate and save the “primitive” aliens, yet they remain unsuccessful. The episode concludes with disquieting and unresolvedly painful images of an eventually genocidal race war.

Considering this general representational practice, the rare cases in which Star Trek does not follow its own rule deserve particular attention. One such exception is that Star Trek addresses one, and only one, ethno-racial group directly—Native Americans. In his The White Man’s Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present ,Robert Berkhofer’s proceeds from the premise that “Native Americans were and are real, but [that] the Indian was a White invention and still remains largely a White image, if not a stereotype.” 5 to trace the trajectory of that image from the first colonial encounters to 20th century cultural productions. His analyses provides a frame of reference to judge how far Star Trek ’s representational practices perpetuate or challenge a traditional image-making which, as Berkhofer outlines, has been heavily involved in the colonial business of dis-empowering the Other.

The only ethno-racial group the program addresses in non-defamiliarized form is not African Americans (the largest “racial minority” in the United States) or Latinos (the fastest-growing “minority”) but Native Americans, a group with minimal visibility and demographic impact, yet of considerable cultural presence. Star Trek ’s choice of Native Americans becomes even more interesting when one takes into consideration that the program explicitly hails from the cultural tradition of the Western—both Roddenberry’s oft-quoted description of Trek as “ Wagon Train to the stars” and TOS ’ and STNG ’s designation of space as the “final Frontier” in their respective title sequences evidence this cultural association. “Indians” emerge from this context as a group that evokes a highly idealized and distorted image of one period in American history, mostly set in the 19th century, that mainstream American culture nostalgically yearns for as a cultural scenario that epitomizes “America” like no other. On the other hand, however, Native Americans also represent the United States’ history as a colonizer, a history the cultural narratives of the Frontier repress just as vehemently as Star Trek represses the colonial implications in its own narrative framework of interstellar “exploration.”

Three episodes cover the whole range of Trek ’s representation of Native Americans from the earliest instance in Star Trek: The Original Series to Star Trek: Voyager ’s recurring Native American character, Commander Chakotay. First, in TOS “The Paradise Syndrome,” the Enterprise arrives on an alien planet, where an accident wipes out Capt. Kirk’s memory. He is soon after found by the planet’s inhabitants who resemble Earth’s Native Americans. Due to the circumstances of Kirk’s sudden appearance, the tribe takes him for a god and adopts him into their community. The amnesic Captain, taking on the name “Kirok”, for a time enjoys the simple life, he gets married and is happy to learn that his wife is pregnant. After a while, however, the tribe find out that “Kirok” does not have supernatural powers, and they stone him and his wife. In the last minute, the Enterprise, having finally found its Captain, steps in and beams the two away from the site of their execution, yet while Kirk can be saved, his wife and unborn child die.

Although standing apart from the other, later episodes featuring Native Americans which are all linked through a common narrative thread, the episode introduces important aspects of Star Trek ’s representation of Native Americans, a representational practice that quite clearly continues traditional Western image-making of the “Indian.” The Native American tribe, 6 whose presence the narrative rather clumsily explains as being brought there by some mysterious aliens who wanted to save them from extinction, serves as the symbolic counterpoint to the technologically and socially advanced life on a starship. The social “evolution” Trek so stresses for humanity seems not to take place within Native American culture—the tribe’s way of life in the 23rd century still resembles that of the 19th century, i.e. of the brief historical period from which the cultural image of the „Indian“ originates and to which popular representations obsessively return. 7 The image the episode draws of Native Americans clearly hails from the notion of the “noble savage,”the “positive” version of the dichotomous Western image of the “Indian.” 8 It entails a romantic yearning for the simple life Native Americans come to represent, a life decidedly free of technology and complex social structures, while at the same time marking that way of life as clearly inferior (and therefore doomed to extinction).

The episode evokes this inferiority in several ways, employing well-established cultural strategies. For example, it is quite typical that the White individual coming into the Native American tribe “naturally” takes on a leadership position, thus implying that, even without any of the institutional power he might be able to draw on in his “civilized” life, his superiority is so obvious that even the “natives” notice it. In addition, the apparent lack of social development the episode implies also designates Native Americans as inferior to a humanity as imagined by Star Trek which, it becomes painfully obvious here, does not include every human community. This aspect of the tribe’s image is particularly important, not only because it makes Native Americans different from the core group in Star Trek ’s most central social quality, but also because it rules out the possibility of Native Americans ever joining the core group. A community that is unable to adapt to changing social and technological conditions, it seems to be the lesson in Social Darwinism the episode inevitably entails, will have to die sooner or later.

Taking the thus highly conservative “The Paradise Syndrome” as a point of reference, it is interesting to look at the ways in which subsequent episodes both perpetuate and change Star Trek: The Original Series ’ representational practices. Chronologically, the next episode is STNG ’s “Journey’s End,” in which the Enterprise is ordered to remove a community of Native Americans from a planet on which they had settled. This time, the episode gives a more elaborate explanation of the tribe’s presence on the alien planet: The community left Earth many years ago in order to search for land where they could build a new home. 9 The episode makes clear that the Native Americans had to go on that journey only because they had been robbed of their homeland and that they were looking not just for any piece of land but for one with which they could enter a spiritual relationship as they had done with their original homeland.

Looking more closely at the role in which the episode thus casts Native Americans reveals a highly interesting colonial narrative. “Journey’s End” is able to address colonialism directly—an issue it uneasily strives to reject in the subplot concerning Capt. Picard 10 —only in a narrative that, first, draws on the Native Americans’ role in a historical colonial encounter, and that then imagines a scenario in which it reverses that role. More specifically, the episode can only develop a convincing narrative of a colonizer who refuses to give up the land of which he has taken possession by casting a group in the role of colonizer which has previously undergone the experience of being colonized. Within Star Trek ’s multicultural framework, Native Americans emerge as (possibly) the only group who can explicitly act as colonizer and still motivate audience sympathies.

There is another subplot in “Journey’s End” that points to a second narrative function Native Americans serve in Star Trek ’s contemporary multicultural economy. When the Enterprise becomes involved in the business of re-locating the tribe, Wesley Crusher, the son of the ship’s doctor, happens to be on board. Currently training to become a Starfleet officer, Wesley is in a deep personal crisis concerning what he wants to do with his life, a crisis that manifests itself in rebellious behavior against authorities as well as against his friends. A member of the Native American tribe takes interest in him, who later turns out to be the alien “the traveler” who had predicted for Wesley an extraordinary future several years ago and who had now returned to take Wesley with him on a search for new levels of existence. Significantly, then, this alien, who represents one of Star Trek ’s most esoteric storylines, chooses a Native American identity to motivate the discontent White teenager Wesley Crusher to pay attention to his spiritual self. Even more so, once Wesley has made the decision to join the traveler in search for places “where thought and energy meet,” the alien instructs Wesley to begin his studies in the Native American community because they supposedly have special insights that could lead him on the right path.

Native Americans clearly take up the function of spiritual mediator here. They thus fill a void in the image of Star Trek ’s core group, which the program so insists on imagining as rational and forward-looking that there seems to be no room for developing a spiritual identity. This phenomenon allows two conclusions concerning Trek ’s representational politics. First, it points to contemporary multi-culturalism’s need for spirituality, a need that apparently grows more urgent the more the multicultural core group stresses its own tolerance, which is a decidedly rational concept. Second, it illustrates how multi-culturalism is still incapable of fusing that spirituality and rationality. Spirituality needs to be represented by some ethnic Other, a role, Star Trek demonstrates, that Native Americans still fit exceedingly well. The fact that the rational self can never be spiritual, however, inevitably implies that the spiritual Other also cannot be rational. This conclusion not only imposes itself by conversion, but also because, otherwise, the Other would be superior to the member of the Eurocentric core group, a hierarchical distribution Star Trek ’s evolutionary logic has certainly not intended. Traditional White images of the “Indian” silence any suspicions of aboriginal superiority by making sure to mention the natives’ impending genocide, a narrative element that not only produces the sentimental effect desired by the romantic genre in which the texts are typically written, but which also clearly states that spirituality is a luxury in the evolutionary struggle for existence. Star Trek , symptomatically, employs that element as well. In both episodes the Native Americans are under threat and need the help of the Federation in order to survive. In “The Paradise Syndrome”, the planet on which the tribe lives is about to be destroyed by an asteroid and only the Enterprise’s technological know-how can prevent the catastrophe. In “Journey’s End” Picard gets his only moments as the forceful and determined leader he usually is when he protects the Native Americans from the violent Cardassians under whose jurisdiction the tribe’s settlement now falls. Star Trek ’s multicultural imaginary thus perpetuates central elements of traditional White narratives of the “Indian,” which maintain that the “Indian” only stays “Indian” as long as he remains untouched by civilization, a logic which, in itself, already dooms Native Americans to extinction:

Since Whites primarily understood the Indian as an antithesis to themselves, the civilization and Indianness as they defined them would forever be opposites. […] If the Indian changed through the adoption of civilization as defined by Whites, then he was no longer truly Indian according to the image […]. 11

Although Star Trek seems to be aware of the ludicrousness of a Native American culture that remains unchanged through centuries of dramatic social and technological development, the program still cannot shed the mutually exclusive logic of the rationality versus spirituality binarism. Already “Journey’s End” attempts to update the Native American culture it imagines by having the members of the tribe not just encounter their own spirits in their vision-rituals but also the gods of other species. The effort to portray a Native American culture that convincingly fits in the 24th century becomes even more obvious in the context of Commander Chakotay. That VOY -character initially does appears to personify the synthesis of rationality and spirituality: He is a Starfleet officer, obviously capable of functioning in such a highly advanced en-vironment, yet he holds on to his “Indian roots.” This synthesis particularly manifests itself in the character’s visual appearance, wearing a Starfleet uniform yet having his “In-dianness” marked by a facial tattoo. Counterbalancing this interesting visual coding, however, is Chakotay’s recurring narrative function as, again, the ship’s spiritual authority. Whenever Capt. Janeway is in doubt concerning the decisions she has to make, she consults with Chakotay to, quite literally, borrow his spiritual helpers. Filmic codes mark these vision quest scenes as extraordinary, standing apart from the rest of VOY ’s televisual narrations: the ritual words Chakotay speaks, “A Cuchi Moya,” remain in what appears to be his native language—a rather surprising phenomenon con-sidering Star Trek ’s ever-present “Universal Translator” which automatically translates even the most distant alien language into convenient English—and the scenes are accompanied by a specific musical theme featuring panpipes, an instrument most popularly associated with South American Indians. The scenes thus not only establish a clear contrast to the program’s otherwise “rational” storylines, but they also employ, again, well-worn imagery to evoke romantic stereotypes of the “Indian.” Although Star Trek: Voyager hence makes an explicit effort to draw a more nuanced picture of Native American spirituality, the program is still unwilling to complicate the binary construction of the spiritual versus the rational.

I want to use the character of Chakotay to address another problematic aspect of Native American representations: casting. As Berkhofer observes, film producers (until quite recently) frequently hired White and Asian actors to play “Indian” roles, and if they did cast Native American actors “for background action,” 12 they did so completely insensitive to tribal affiliations. I would even extend Berkhofer’s observations in claiming that—until the large-scale success of Dances With Wolves (1990) severely challenged mainstream audiences’ viewing habits—actors and actresses who were marked by any ethno-racial difference could play the “Indian.” For example, the only “Indian” entire generations of German audiences could see—the Karl May character “Winnetou” featured in several German films made in the 1960s—was played by a White French actor. Along precisely the same lines, Miramanee, “Kirok”’s short-term wife in “Paradise Syndrome,” was played by an actress by the name of Sabrina Scharf.

When developing the figure of Chakotay, VOY ’s producers seemed to have been aware of these as well as other flaws in traditional representations of Native Americans and they were apparently determined to draw a more correct image. This effort becomes evident in that the VOY production team not only hired a science consultant—as had been the rule since STNG —but that they also hired an expert, Jamake Highwater, to check each script for accuracy concerning Native American issues. 13 Despite such obvious efforts not to repeat the ignorant White images of Native Americans of the past, however, VOY did perpetuate traditional patterns in casting the character of Chakotay.

First of all, while clearly striving to mark Chakotay as Native American, writers and producers seemingly regarded the character’s tribal affiliation as only marginal to the figure’s identity. Initially, Chakotay’s tribal ancestry remained unresolved for a long time. 14 It was then decided upon as Sioux (the Plains Indian again), to be soon after changed to Hopi, to be finally left open again. Indeed, VOY began employing the character of Chakotay as precisely that kind of generic “Indian,” referring to him only as being “‘from a colony of American Indians.’” 15 One contributor to the <[email protected]> discussion group summarizes many viewers’ dissatisfaction with seeing, once more, a generic “Indian”:

[…T]he show can be faulted for not creating a tribal identity for Chakotay, which would help frame him a little better. All we know about his culture is that he has a tattoo, a spirit guide, and uses a machine to imitate the effects of peyote. Also, haunting, “native” reed in-struments play on those rare occasions we get to see his private living space […].

It was not until audience pressure concerning another representational faux-pas forced the production team to write a specific tribal heritage into the character that this generic Indian-ness was specified.

This second faux-pas concerns the actor casted to play Chakotay. Robert Beltran is Mexican American, and although he tried to justify his playing an “Indian” role by evoking the Mestizo heritage of many Mexicans, 16 many viewers experienced his presence as “yet another non-Indian actor […] in a part that is identifiably Indian and uses trappings from the culture.” 17 Only very gradually, and at Beltran’s own suggestion, did the producers effectively solve the problem of their own casting decision by specifying Chakotay’s tribal affiliation as “south of border”, i.e. Mayan, Aztec or Inca. 18

Although VOY thus explicitly sets out to draw an image of Native Americans that satisfies audience’s heightened sensitivities regarding the accuracy of such representations, the program clearly fails in its own project of political correctness. In this context, it is ironic that the only moments in which VOY ’s narrations do lastingly disrupt traditional re-presentational politics lie outside of the type of self-conscious multicultural discourse to which Star Trek usually subscribes. This lasting disruption is achieved when VOY uses humor to address stereotypes of Native Americans. Two such instances exemplify the mechanisms at work. First, in VOY ’s pilot episode, “The Caretaker,” Tom Paris tries to save Chakotay’s life in an extremely tight situation. While Chakotay attempts to dissuade Paris from risking his own life, Paris jokes about how, if he succeeds, Chakotay would be forever in his debt. To his question, “Isn’t that some Indian custom?” Chakotay replies, “Wrong tribe!”. Second, in the two-part episode “Basics,” the starship Voyager falls into the hands of the hostile Kazons, who maroon the crew on an inhospitable planet. Being robbed of all their technology, the crew has to struggle with the most quotidian problems in order to survive. They, first of all, try to make a fire. When they remain unsuccessful for a long time, Chakotay remarks dispiritedly that he was the only Indian for light-years around and not even capable of making a fire.

In both these scenes, humor is used to relax a tense situation. The scenes do not set out to address Native American culture, they rather evoke “Indianness” in a mere functional way, almost incidentally. In order to achieve this effect of relaxation, the scenes bring up specific stereotypes of Native Americans, which the “real” Indian Chakotay then proves wrong. He does that, in the first scene, by pointing to the great diversity of existing Native American cultures in contrast to the generic “Indian” culture the stereotypical image holds on to, and in the second scene, by demonstrating that the skills stereotypically ascribed to Native Americans belong to a specific historical environment and that they do get lost once they are no longer practiced.

The scenes are effective in challenging the logic of traditional image-making for two reasons. First, they manage to address and effectively critique central problems in the cultural image of the “Indian” which Star Trek: Voyager could not prevent itself from repeating. And, second, the critique works in these scenes precisely because they leave the self-conscious multicultural mode the series otherwise adheres to. The scenes are among the few moments when Star Trek allows itself to acknowledge the existence of cultural stereotypes among its own core group, something the program is only able to do—without disrupting Trek ’s very premise—in a humorous mode. The laughter these scenes produce allows the core-group-identified audience to interrogate their own prejudice in a context that is unthreatening yet that clearly endorses the Native American point of view, as, to put it casually, the laughs are on the ignorant Whites.

In conclusion, an analysis of Native Americans as “non-estranged Others” reveals symptomatic features of Star Trek ’s imagination of core- and marginalized groups. This imagination is a decidedly complex one, negotiating between traditional representational practices, to which both producers and audiences are accustomed, and Star Trek ’s own multicultural image. Out of this ideological tension, Star Trek ’s re-presentational politics emerge as a constantly up-dated version of a Western imaginary in which Native Americans continue to merely serve a symbolic function for a decidedly White core culture, providing a projection space in which those of that core culture’s needs and desires that would disrupt the group’s self-image can be played out. These needs and desires encompass the yearning for a spirituality that has been written out of White identity in the process of its multiculturalization, or the need for a cultural referent that allows the core culture to still imagine certain narrative constellations typical of the Science Fiction genre, such as the sympathetic colonizer, when the group’s self-imposed multicultural conscience marks these as taboo. Thus, although the visual surface of Star Trek ’s representational practices does adapt to changing audience sensibilities, the representational politics remain essentially unchanged. The program can truly challenge that politics only in those moments when it leaves its own safely contained multicultural logic in humorous narrations that transgress the limitations of a marketable political correctness.

1 Jenny Wolmark, Aliens and Others: Science Fiction, Feminism and Postmodernism (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1994).

2 Quoted in: John Tulloch and Henry Jenkins, Science Fiction Audience: Watching Doctor Who and Star Trek (New York: Routledge, 1995) 4.

3 Stephen E. Whitfield and Gene Roddenberry, The Making of Star Trek (New York: Ballantine, 1968) 40.

4 Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman, Creating The Next Generation (London: Boxtree, 1995) 128.

5 Robert F. Berkhofer, The White Man‘s Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present (New York: Vinatge Books, 1979) 3.

6 Judging from the paraphernalia the episode features, the tribe appears to belong to the family of the Sioux, the one Native American culture “Indians” have stereotypically been reduced to. See Berkhofer, The White Man’s Indian , 89-90.

7 See Berkhofer, The White Man’s Indian , 97.

8 For a succinct discussion of the “good Indian”—“bad Indian” dichotomy, see Berkhofer, The White Man’s Indian , 28-30.

9 This episode as well as later ones suggest that this tribe was not the only one to leave Earth. The implied question then, whether there are still any Natives Americans left on Earth, dangerously writes a late “success” into the history of the colonial genocide in North America.

10 It is revealed that Picard, who uneasily agredees to remove the tribe in order to prevent a large-scale interplanetary war, has an ancestor who participated in brutally putting down the Pueblo revolt of 1618. While the episode thus evokes historical guilt, it has, at the same time, Picard reject this responsibility, a point of view the narrative clearly endorses.

11 Berkhofer, The White Man’s Indian , 29.

12 Ibid., 103.

13 Stephen Edward Poe, Star Trek Voyager : A Vision of the Future (New York: Pocket, 1998) 288.

14 Ibid. , 206.

15 Ibid. , 221.

16 Ibid. , 302.

17 Quoted from a contribution to the online-discussion-group <[email protected]>.

Suggested Citation

Star Trek: 10 Things You Never Knew About Chakotay

He was Star Trek: Voyager's leading Maquis-turned-Officer, but how well do we really know Chakotay?

Chakotay was a first in many ways for Star Trek. He was an officer who had left the service, only to return when the situation demands. He was to have touched the lives of many regular names and faces, and also serve as an ambassador for Native American people in the franchise. The genesis of his character is both fascinating, and riddled with issues.

Originally introduced, albeit not by name (or appearance) in Star Trek: The Next Generation, Chakotay was one of the main characters in Voyager for its first few seasons, before settling into more of a supporting role once season four dawned. Robert Beltran, who played him, has never been shy in airing his opinions on Chakotay's journey, or lack thereof.

However, with both the actor and character confirmed as returning in a recurring role for Star Trek: Prodigy, now is the time to revisit not only the genesis of Starfleet and the Maquis' #1 in the Delta Quadrant, but also where the character ended up by the time that Star Trek: Voyager came to a close. What's next for the man who made the term Acoochimoya famous?

10. He Was The First

The character who became Chakotay was one of the first sketched ideas for the then-unnamed Star Trek: Voyager. He was inspired by the positive response to the character of Uhura in the Original Series and more specifically the positive representation for African-American people that came with the character.

'Chakotay' was to serve in this same role for Native American people, though it took quite a while to settle on exactly how best to depict him. Initially, the Tribe from which he originated wasn't chosen, and he was a far more 'mystical' man. He was also written to have a prior connection with Captain Janeway.

That element was dropped, as was much of his mysticism. The character bible switched the word 'mystic' to 'complex' instead. It also changed another aspect, namely in that it hadn't been him specifically that chose to abandon Earth, but his people as a whole. That way, his return to Starfleet was, for a time, a means of differentiating himself from his Tribe.

The writers settled on Chakotay's people being descendants of the Rubber Tree People, which was later explored in the episode Tattoo.

Writer. Reader. Host. I'm Seán, I live in Ireland and I'm the poster child for dangerous obsessions with Star Trek. Check me out on Twitter @seanferrick

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Star Trek: Voyager

Pulled to the far side of the galaxy, where the Federation is seventy-five years away at maximum warp speed, a Starfleet ship must cooperate with Maquis rebels to find a way home. Pulled to the far side of the galaxy, where the Federation is seventy-five years away at maximum warp speed, a Starfleet ship must cooperate with Maquis rebels to find a way home. Pulled to the far side of the galaxy, where the Federation is seventy-five years away at maximum warp speed, a Starfleet ship must cooperate with Maquis rebels to find a way home.

- Rick Berman

- Michael Piller

- Jeri Taylor

- Kate Mulgrew

- Robert Beltran

- Roxann Dawson

- 427 User reviews

- 26 Critic reviews

- 33 wins & 84 nominations total

Episodes 168

Photos 2084

- Capt. Kathryn Janeway …

- Cmdr. Chakotay …

- Lt. B'Elanna Torres …

- Lt. Tom Paris …

- The Doctor …

- Lt. Tuvok …

- Ensign Harry Kim …

- Lt. Ayala …

- Voyager Computer …

- Seven of Nine …

- William McKenzie …

- Naomi Wildman

- Ensign Brooks

- Science Division Officer …

- Jeri Taylor (showrunner)

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Stellar Photos From the "Star Trek" TV Universe

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia When auditioning for the part of the holographic doctor, Robert Picardo was asked to say the line "Somebody forgot to turn off my program." He did so, then ad-libbed "I'm a doctor, not a light bulb" and got the part.

- Goofs There is speculation that the way the Ocampa are shown to have offspring is an impossible situation, as a species where the female can only have offspring at one event in her life would half in population every generation, even if every single member had offspring. While Ocampa females can only become pregnant once in their lifetime, if was never stated how many children could be born at one time. Kes mentions having an uncle, implying that multiple births from one pregnancy are possible.

Seven of Nine : Fun will now commence.

- Alternate versions Several episodes, such as the show's debut and finale, were originally aired as 2-hour TV-movies. For syndication, these episodes were reedited into two-part episodes to fit one-hour timeslots.

- Connections Edited into Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: Inter Arma Enim Silent Leges (1999)

User reviews 427

- breckstewart

- Apr 14, 2019

- How many seasons does Star Trek: Voyager have? Powered by Alexa

- Why do the Nacelles of the Voyager pivot before going to warp?

- Is it true there is a costume error in the first season?

- How many of Voyager's shuttles were destroyed throughout the course of the show?

- January 16, 1995 (United States)

- United States

- Heroes & Icons

- Memory Alpha, the Star Trek wiki

- Star Trek: VOY

- Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant - 6100 Woodley Avenue, Van Nuys, Los Angeles, California, USA

- Paramount Television

- United Paramount Network (UPN)

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Technical specs

- Runtime 44 minutes

- Dolby Digital

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed

Star Trek | How Roddenberry's Future Failed Native Americans

Despite its noble intentions, from 'Kirok' to Chakotay, the Star Trek franchise has failed Native Americans at almost every turn.

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share via Email

The Star Trek shows can be seen virtually all around the globe, in countries ranging from the Czech Republic to South Africa or Indonesia. The show has, since its inception in the mid-1960s, presented itself to audiences as a science fiction program that explicitly sets out to compose a future in which people of all races, species, and genders live together harmoniously.

Gene Roddenberry, the man who created Star Trek , cast himself in the role of a visionary whose quotable insights into the destiny of the human “race” became the core of the program’s market identity. Among such often quoted soundbites were, for example:

“Intolerance in the 23rd century? Improbable! If man survives that long, he will have learned to take a delight in the essential differences between men and between cultures.” - Gene Roddenberry, qouted in The Making of Star Trek (1968).

"Diversity contains as many treasures as those waiting for us on other worlds. We will find it impossible to fear diversity and to enter the future at the same time." - Gene Roddenberry, quoted in Creating The Next Generation (1995).

Star Trek ’s effort to construct for itself a multicultural image can be traced to primarily two strategies. First, the program has been striving for a diverse cast of characters, from The Original Series featuring a Black woman and an Asian man among its bridge crew, to Deep Space Nine and Voyager showcasing an African American (male) and a (White) female in their respective captain’s seats. The second strategy lies in the kinds of stories Star Trek chooses to tell. With reliable regularity, the program features self-conscious ‘issue’-episodes that are obviously designed to tell a parable on current political issues.

These episodes follow a typical pattern in projecting real-life racial (or other) issues onto alien species. In ‘Let That Be Your Last Battlefield’ ( TOS – S3, Ep15), the crew of Enterprise encounter the humanoid alien Lokai, whose face is half black and half white, and who is apparently on the run in a stolen shuttlecraft. Soon, a law enforcement officer, Bele, comes hunting after Lokai. The two look exactly alike, only Lokai is white on the right side of his body and black on the left, while Bele’s colors are distributed the other way around. When Lokai urgently pleads with the Enterprise crew to grant him political asylum, they learn that the aliens’ planet is riven by a deadly race war, a war which, by the episode’s end, will have killed all life on the planet. When confronted with the madness of ultimately genocidal hatred, the crew of Enterprise tries to make sense of it by putting the conflict in the context of their own (human) history:

Chekov: There was persecution on Earth once. I remember reading about it in my history class. Sulu: Yes, but it happened way back in the 20th century. There is no such primitive thinking today. - ‘Let That Be Your Last Battlefield’ , The Original Series – S3, Ep15.

The episode is thus able to address the late 1960s’ reality of brutal race riots in a safe and unthreatening context. It simplifies the complex structure of race relations by locating the source of all tensions in each race’s dislike of the other’s physical appearance, a difference the episode seemingly strives to make as superficial and ludicrous as possible. The dialogue between Chekov and Sulu then affirms that humanity has long overcome this state of racial prejudice, thus casting themselves in a role of enlightened superiority. In striking similarity to the (ideo-)logic of the colonial encounter, the crew of Enterprise attempt to educate and save the “primitive” aliens, yet they remain unsuccessful. The episode concludes with disquieting and unresolvedly painful images of an eventually genocidal race war.

Considering this general representational practice, the rare cases in which Star Trek does not follow its own rule deserve particular attention. One such exception is that Star Trek addresses one, and only one, ethno-racial group directly—Native Americans.

Paradise Lost

Star Trek ’s choice becomes even more interesting when one takes into consideration that the program explicitly hails from the cultural tradition of the Western—both Roddenberry’s oft-quoted description of Star Trek as “Wagon Train to the stars” and TOS ’ and The Next Generation’s designation of space as “the final frontier” in their respective title sequences evidence this cultural association. Indigenous Americans emerge from this context as a group that evokes a highly idealized and distorted image of one period in American history, mostly set in the 19th century, that mainstream American culture nostalgically yearns for as a cultural scenario that epitomizes ‘America’ like no other. On the other hand, however, Native Americans also represent the United States’ history as a colonizer, a history the cultural narratives of the frontier repress just as vehemently as Star Trek represses the colonial implications in its own interstellar “exploration.”

Three episodes cover the whole range of Star Trek ’s representation of Native Americans from the earliest instance in Star Trek: The Original Series to Star Trek: Voyager ’s recurring Native American character, Commander Chakotay. First, in TOS ‘The Paradise Syndrome’ (S3, Ep3), Enterprise arrives on an alien planet, where an accident wipes out Captain Kirk’s memory. He is soon after found by the planet’s inhabitants who resemble Earth’s Native Americans. Due to the circumstances of Kirk’s sudden appearance, the tribe takes him for a god and adopts him into their community. The amnesic captain, taking on the name ‘Kirok’ for a time enjoys the simple life, he gets married and is happy to learn that his wife is pregnant. After a while, however, the tribe finds out that ‘Kirok’ does not have supernatural powers, and they stone him and his wife. At the last minute, Enterprise, having finally found its Captain, steps in and beams the two away from the site of their execution, yet while Kirk can be saved, his wife and unborn child die.

Although standing apart from the other, later episodes featuring Native Americans which are all linked through a common narrative thread, the episode introduces important aspects of Star Trek ’s representation of Native Americans, a representational practice that quite clearly continues traditional Western image-making of the ‘Indian’. The Native American tribe (inspired to some extent by the popular image of the Sioux people), whose presence the narrative rather clumsily explains as being brought there by some mysterious aliens who wanted to save them from extinction, serves as the symbolic counterpoint to the technologically and socially advanced life on a starship. The social ‘evolution’ Star Trek so stresses for humanity seems not to take place within Native American culture—the tribe’s way of life in the 23rd century still resembles that of the 19th century.

The image the episode draws of Native Americans clearly hails from the racist notion of the ‘noble savage’ – the ‘positive’ version of the Western image of the ‘Indian’. It entails a romantic yearning for the simple life Native Americans come to represent, a life decidedly free of technology and complex social structures, while at the same time marking that way of life as clearly inferior (and therefore doomed to extinction).

The episode evokes this inferiority in several ways, employing well-established cultural strategies. For example, it is quite typical that the White individual coming into the Native American tribe ‘naturally’ takes on a leadership position, thus implying that, even without any of the institutional power he might be able to draw on in his ‘civilized’ life, his superiority is so obvious that even the ‘native’ notice it. In addition, the apparent lack of social development the episode implies also designates Native Americans as inferior to humanity as imagined by Star Trek . This aspect of the tribe’s image is particularly important, not only because it makes Native Americans different from the core group in Star Trek ’s most central social quality, but also because it rules out the possibility of Native Americans ever joining the core group. A community that is unable to adapt to changing social and technological conditions, it seems to be the lesson in Social Darwinism the episode inevitably entails, will have to die sooner or later.

Fellow Travelers

Taking the highly conservative ‘The Paradise Syndrome’ as a point of reference, it is interesting to look at the ways in which subsequent episodes both perpetuate and change Star Trek: The Original Series’ representational practices. Chronologically, the next episode is The Next Generation’s ‘Journey’s End’ (S7, Ep20), in which Enterprise is ordered to remove a community of Native Americans from a planet on which they had settled. This time, the episode gives a more elaborate explanation of the tribe’s presence on the alien planet: The community left Earth many years ago in order to search for land where they could build a new home. The episode makes clear that the Native Americans had to go on that journey only because they had been robbed of their homeland and that they were looking not just for any piece of land but for one with which they could enter a spiritual relationship as they had done with their original homeland.

Looking more closely at the role in which the episode casts Native Americans reveals a highly interesting colonial narrative. ‘Journey’s End’ is able to address colonialism directly—an issue it uneasily strives to reject in the subplot concerning Captain Picard — only in a narrative that, first, draws on the Native Americans’ role in a historical colonial encounter, and that then imagines a scenario in which it reverses that role. More specifically, the episode can only develop a convincing narrative of a colonizer who refuses to give up the land of which he has taken possession by casting a group in the role of the colonizer who has previously undergone the experience of being colonized. Within Star Trek ’s multicultural framework, Native Americans emerge as (possibly) the only group who can explicitly act as colonizers and still motivate audience sympathies.

There is another subplot in ‘Journey’s End’ that points to a second narrative function Native Americans serve in Star Trek ’s contemporary multicultural economy. When Enterprise becomes involved in the business of re-locating the tribe, Wesley Crusher, the son of the ship’s doctor, happens to be on board. Currently training to become a Starfleet officer, Wesley is in a deep personal crisis concerning what he wants to do with his life, a crisis that manifests itself in rebellious behavior against authorities as well as against his friends. A member of the Native American tribe takes interest in him, who later turns out to be the alien ‘the Traveler’ who had predicted for Wesley an extraordinary future several years ago and who had now returned to take Wesley with him on a search for new levels of existence.

Significantly, then, this alien, who represents one of Star Trek ’s most esoteric storylines, chooses a Native American identity to motivate the discontent white teenager Wesley Crusher to pay attention to his spiritual self. Even more so, once Wesley has made the decision to join the Traveler in search for places “where thought and energy meet,” the alien instructs Wesley to begin his studies in the Native American community because they supposedly have special insights that could lead him on the right path.

Native Americans clearly take up the function of spiritual mediator here. They fill a void in the image of Star Trek ’s core group, which the program so insists on imagining as rational and forward-looking that there seems to be no room for developing a spiritual identity. This phenomenon allows two conclusions concerning Trek ’s representational politics. First, it points to contemporary multiculturalism’s need for spirituality, a need that apparently grows more urgent the more the multicultural core group stresses its own tolerance, which is a decidedly rational concept. Second, it illustrates how multiculturalism is still incapable of fusing that spirituality and rationality.

Spirituality needs to be represented by some ethnic Other, a role, Star Trek demonstrates, that Native Americans still fit exceedingly well. The fact that the rational self can never be spiritual, however, inevitably implies that the spiritual Other also cannot be rational. This conclusion not only imposes itself by conversion, but also because, otherwise, the Other would be superior to the member of the Eurocentric core group, a hierarchical distribution Star Trek’s evolutionary logic has certainly not intended. Traditional White images of the ‘Indian’ silence any suspicions of aboriginal superiority by making sure to mention the natives’ impending genocide, a narrative element that not only produces the sentimental effect but also clearly states that spirituality is a luxury in the evolutionary struggle for existence.

A Cuchi Moya

Although Star Trek seems to be aware of the ludicrousness of a Native American culture that remains unchanged through centuries of dramatic social and technological development, the program still cannot shed the mutually exclusive logic of rationality versus spirituality. Already ‘Journey’s End’ attempts to update the Native American culture it imagines by having the members of the tribe not just encounter their own spirits in their vision rituals but also the gods of other species. The effort to portray a Native American culture that convincingly fits in the 24th century becomes even more obvious in the context of Commander Chakotay.

That Voyager character initially does appears to personify the synthesis of rationality and spirituality: He is a Starfleet officer, obviously capable of functioning in such a highly advanced environment, yet he holds on to his ‘Indian’ roots. This synthesis particularly manifests itself in the character’s visual appearance, wearing a Starfleet uniform yet having his ‘Indianness’ marked by a facial tattoo. Counterbalancing this interesting visual coding, however, is Chakotay’s recurring narrative function as, again, the ship’s spiritual authority. Whenever Captain Janeway is in doubt concerning the decisions she has to make, she consults with Chakotay to, quite literally, borrow his spiritual helpers.

Cliches mark these vision quest scenes as extraordinary, standing apart from the rest of Voyager’ the ritual words Chakotay speaks, ‘A Cuchi Moya’, remain in what appears to be his native language—a rather surprising phenomenon considering Star Trek ’s ever-present Universal Translator which automatically translates even the most distant alien language into convenient English—and the scenes are accompanied by a specific musical theme featuring panpipes, an instrument most popularly associated with South American Indians. The scenes thus not only establish a clear contrast to the program’s otherwise ‘rational’ storylines, but they also employ, again, well-worn imagery to evoke romantic stereotypes of the ‘Indian’. Although Star Trek: Voyager hence makes an explicit effort to draw a more nuanced picture of Native American spirituality, the program is still unwilling to complicate the binary of the spiritual versus the rational.

The character of Chakotay also surfaces another problematic aspect of Native American representation: casting. For much of film and TV history, producers (until quite recently) frequently hired white and Asian actors to play ‘Indian’ roles, and if they did cast Native American actors “for background action,” they did so completely insensitive to tribal affiliations.

When developing the figure of Chakotay, Voyager ‘s producers seemed to have been aware of these as well as other flaws in traditional representations of Native Americans, and they were apparently determined to draw a more correct image. This effort becomes evident in that the Voyager production team not only hired a science consultant—as had been the rule since The Next Generation —but that they also hired an expert, Jamake Highwater, to check each script for accuracy concerning Native American issues. Despite such obvious efforts not to repeat the ignorant white images of Native Americans of the past, Voyager did perpetuate traditional patterns in casting the character of Chakotay.

First of all, while clearly striving to mark Chakotay as Native American, writers and producers seemingly regarded the character’s tribal affiliation as only marginal to the figure’s identity. Initially, Chakotay’s tribal ancestry remained unresolved for a long time. It was then decided upon as Sioux (the Plains Indian again), to be soon after changed to Hopi, to be finally left open again. Indeed, Voyager began employing the character of Chakotay as precisely that kind of generic ‘Indian’, referring to him only as being “‘from a colony of American Indians.’” One contributor to the <[email protected]> discussion group summarizes many viewers’ dissatisfaction with seeing, once more, a generic ‘Indian’:

[…T]he show can be faulted for not creating a tribal identity for Chakotay, which would help frame him a little better. All we know about his culture is that he has a tattoo, a spirit guide, and uses a machine to imitate the effects of peyote. Also, haunting, “native” reed in-struments play on those rare occasions we get to see his private living space […].

It was not until audience pressure concerning another representational faux-pas forced the production team to write a specific tribal heritage into the character that this generic ‘Indian’-ness abated.

This second faux-pas concerns the actor cast to play Chakotay. Robert Beltran is Mexican-American, and although he tried to justify his playing an ‘Indian’ role by evoking the Mestizo (mixed European/indigenous) heritage of many Mexicans, many viewers experienced his presence as “yet another non-Indian actor […] in a part that is identifiably Indian and uses trappings from the culture.” Only very gradually, and at Beltran’s own suggestion, did the producers effectively solve the problem of their own casting decision by specifying Chakotay’s tribal affiliation as “south of border”, i.e. Mayan, Aztec, or Inca.

Back to Basics

Although Voyager explicitly sets out to draw an image of Native Americans that satisfies the audience’s heightened sensitivities regarding representation, the program clearly fails in its own project. In this context, it is ironic that the only moments in which Voyager does lastingly disrupt traditional representational politics lie outside of the type of self-conscious multicultural discourse to which Star Trek usually subscribes. This is achieved when Voyager uses humor to address stereotypes of Native Americans. Two such instances exemplify the mechanisms at work. First, in the pilot episode, ‘The Caretaker’ (S1, Ep1), Tom Paris tries to save Chakotay’s life in an extremely tight situation. While Chakotay attempts to dissuade Paris from risking his own life, Paris jokes about how, if he succeeds, Chakotay would be forever in his debt.

Chakotay: You get on those stairs, they’ll collapse! We’ll both die! Paris: Yeah? But on the other hand, if I save your butt your life belongs to me. Isn’t that some kind of Indian custom? Chakotay: Wrong tribe. - Star Trek: Voyager , ‘Caretaker’ – S1, Ep1.

Second, in the two-part episode ‘Basics’ (S2, Ep26-S3, Ep1), Voyager falls into the hands of the hostile Kazons, who maroon the crew on an inhospitable planet. Being robbed of all their technology, the crew has to struggle with the most quotidian problems in order to survive. They, first of all, try to make a fire. When they remain unsuccessful for a long time, Chakotay remarks dispiritedly that he was the only Indian for light-years around and not even capable of making a fire.

In both these scenes, humor is used to relax a tense situation. The scenes do not set out to address Native American culture, they rather evoke ‘Indianness’ in a merely functional way, almost incidentally. In order to achieve this effect of relaxation, the scenes bring up specific stereotypes of Native Americans, which the ‘real’ Indian Chakotay then proves wrong. He does that, in the first scene, by pointing to the great diversity of existing Native American cultures in contrast to the generic ‘Indian’ culture the stereotypical image holds on to, and in the second scene, by demonstrating that the skills stereotypically ascribed to Native Americans belong to a specific historical environment and that they do get lost once they are no longer practiced.

The scenes are effective in challenging the logic of traditional image-making for two reasons. First, they manage to address and effectively critique central problems in the cultural image of the ‘Indian’ which Star Trek: Voyager could not prevent itself from repeating. And, second, the critique works in these scenes precisely because they leave the self-conscious multicultural mode the series otherwise adheres to. The scenes are among the few moments when Star Trek allows itself to acknowledge the existence of cultural stereotypes among its own core group, something the program is only able to do—without disrupting Star Trek ’s very premise—in a humorous mode. The laughter these scenes produce allows the core-group-identified audience to interrogate their own prejudice in a context that is unthreatening yet that clearly endorses the Native American point of view, as, to put it casually, the laughs are on the ignorant.

Brad Wright's Conversations in Sci-Fi: The Wright Cut

Brad wright's conversations in sci-fi (abridged), cgi fridays, star trek | a history of starfleet uniforms from fashion disasters to gender equality, upcoming events, brad wright: how to recharge your creativity, teryl rothery: embracing mental health as a fandom - part 5, basingstoke comic con collaboration.

Voyager’s Native American consultant was a fraud

By rachel carrington | feb 26, 2021.

Commander Chakotay, portrayed by Robert Beltran, on Star Trek: Voyager was of Native American descent, but the actor himself is a Mexican American. So it makes perfect sense that the series would hire a Native American to help shape the character of Chakotay. So a man known as Jamake Highwater was brought on board. Highwater claimed that he was of American Indian ancestry, particularly Cherokee, and he was hired for his “Native-American expertise.”

But Jamake Highwater’s real name was Jackie Marks, and he was born in Los Angeles, CA with Jewish ancestry. But, for some reason, he began referring to himself as Highwater in the 1960s, and he became nationally known as an American Indian writer. PBS even adapted his book, The Primal Mind: Vision and Reality in Indian America, as the basis of a documentary about Native American culture, The Primal Mind (1984).

But in 1984, his claims of being Native American began to unravel, but that didn’t stop Marks from continuing his career, and that career actually had a detrimental affect on Beltran’s character. Heavy.com reports that “The development of the Chakotay character, overseen by Highwater, was complicated. Chakotay’s tribal affiliation changed multiple times during early production. According to A Vision of the Future, an analysis of Star Trek: Voyager by Stephen Edward Poe, notes that Chakotay was variously a Sioux, a Hopi, and a Native American with no tribal affiliation during early drafts of the Caretaker pilot script.”

Clearly, Marks couldn’t help enrich Chakotay’s character because he had no personal knowledge of Native Americans, their beliefs, or their customs. Unfortunately, that led to Chakotay simply carrying a label. And that hurt the character’s development. with some fans calling him “a Native American stereotype.”

It’s unknown how Marks obtained his position with Voyager or even if he passed a background check. However he pulled off this monumental scam, for a while, he succeeded. Marks passed away in 2001 with no mention of his Native American ancestry in his obituary.

Next. A first time viewer’s review of Star Trek: Voyager. dark

Jamake Highwater

- View history

"Jamake Highwater" ( 13 February 1931 – 3 June 2001 ; age 70), born Jackie Marks , served as a consultant on Native American culture to Star Trek: Voyager . Though he claimed American Indian ancestry, he was in fact of Eastern European Jewish background. "Highwater" was heavily criticized by actual American Indians for his writings, which typically contained stereotypical and inaccurate depictions of Indian culture. ( A Vision of the Future - Star Trek: Voyager , p.199)

Work on Voyager [ ]

Marks, in his fake identity as "Jamake Highwater", was hired as a consultant on Star Trek: Voyager to advise the producers on Native American culture. His work influenced the development of the Chakotay character, including key details such as animal guides, vision quests and more. One such example is that Michael Piller consulted with him before writing the animal guide subplot for " The Cloud ".

External link [ ]

- Jamake Highwater at Wikipedia

Star Trek: Voyager's Janeway Becoming Ripley From Alien Explained By Producer

- Captain Janeway's "Ripley" moments in "Macrocosm" left a notable impact on Star Trek: Voyager.

- Brannon Braga didn't intend to copy Alien with "Macrocosm," instead wanting to create a dialogue-light episode.

- "Macrocosm" allowed Janeway to showcase new action-hero qualities while retaining her core characteristics.

Star Trek: Voyager 's Executive Producer Brannon Braga explained his real inspiration behind the episode where Captain Janeway (Kate Mulgrew) becomes Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) from Alien . Although both Voyager and Alien are science fiction, there are a lot of differences between the Star Trek and Alien franchises. While Alien focuses on blending horror and suspense with its sci-fi elements, Star Trek almost always takes a more optimistic approach to the future. However, there are occasionally Star Trek episodes that take on more of a horror twist .

One such episode was Voyager season 3, episode 12, "Macrocosm," where an alien virus managed to take over the USS Voyager, mutating to grow at least a meter in length and then proceeding to make Voyager 's cast of characters very sick. As the lone un-infected, Captain Janeway was forced to mount a guerrilla attack on the viruses while the Doctor (Robert Picardo) worked on finding a cure. Along with similar premises, "Macrocosm" seemed to take a lot of influence from Alien , especially in how it portrayed Janeway as its heroine.

Every Upcoming Star Trek Movie & TV Show

Star trek: voyagers janeway alien episode explained by executive producer, braga's intention wasn't actually to copy alien.

Despite Janeway's crusade against the viruses in "Macrocosm" often being compared to Ellen Ripley, Brannon Braga, who wrote the episode's story, claimed it wasn't his intention to create a tribute to Alien . In an interview with Cinefantastique around the time of the episode's release, Braga stated that "Macrocosm" actually rose out of a desire to do a solo character story with very little dialogue , and implied that any comparisons between Janeway and Ripley were completely unintentional. Read Braga's full quote below:

"Sometimes Star Trek can be a little high-and-mighty, talky, moralistic. Sometimes it's just time to have fun. The intention actually began, on my part, to do an episode with no dialogue. I wanted to just do a purely cinematic episode with Janeway and a bunch of weird creatures, these macroviruses, viruses as life-sized creatures. Unfortunately it was impossible to do, and I ended up having to put a couple of acts of dialogue in. I just wanted to do something that felt and looked and smelled differently than most shows. It was not an attempt to make Janeway look like Ripley."

Despite Braga's protestations, it is hard not to see the numerous similarities between Janeway and Sigourney Weaver's iconic Alien role in "Macrocosm." Stripped down to her uniform's undershirt and equipped with a large phaser rifle for defense, Janeway embodied the recognizable sci-fi "final girl" aesthetic popularized by Weaver's portrayal of Ripley in the first Alien film from 1979 . Given what a recognizable character Ripley is thanks to Alien 's popularity, it's no wonder that "Macrocosm" became such a memorable episode of Voyager after it aired.

Why Captain Janeways Ripley Moments In Star Trek: Voyager Are Still So Popular

"macrocosm's" version of janeway is still extremely well-liked.

Despite not being one of Voyager 's most popular episodes, Janeway's "Ripley" scenes in "Macrocosm" left an indelible mark on the series. This is likely due to what a departure Janeway's actions and aesthetic were from how she was usually portrayed on Voyager . "Macrocosm" allowed Janeway to be a true action hero , showing that she was able to handle more than just the scientific and diplomatic aspects of being a Captain.

However, Janeway never lost what made her such a popular character in the first place, including her stubborn determination and fierce loyalty to her crew. Her nearly single-handed defeat of the macrovirus perfectly demonstrated how far she was willing to go to make sure everyone under her protection was safe. The macrovirus itself also likely contributed to the episode's popularity , and demonstrated its longevity when it was brought back as part of Star Trek: Lower Decks ' tribute episode to Voyager , "Two-vix." Lower Decks helped remind audiences just how iconic "Macrocosm" was for Star Trek: Voyager season 3.

Source: Cinefantastique , Vol. 29

Star Trek: Voyager is available to stream on Paramount+ Alien is available to stream on Hulu

Star Trek: Voyager

The fifth entry in the Star Trek franchise, Star Trek: Voyager, is a sci-fi series that sees the crew of the USS Voyager on a long journey back to their home after finding themselves stranded at the far ends of the Milky Way Galaxy. Led by Captain Kathryn Janeway, the series follows the crew as they embark through truly uncharted areas of space, with new species, friends, foes, and mysteries to solve as they wrestle with the politics of a crew in a situation they've never faced before.

Cast Jennifer Lien, Garrett Wang, Tim Russ, Robert Duncan McNeill, Roxann Dawson, Robert Beltran, Kate Mulgrew, Jeri Ryan, Ethan Phillips, Robert Picardo

Release Date May 23, 1995

Genres Sci-Fi, Adventure

Network UPN

Streaming Service(s) Paramount+

Franchise(s) Star Trek

Writers Kenneth Biller, Jeri Taylor, Michael Piller, Brannon Braga

Showrunner Kenneth Biller, Jeri Taylor, Michael Piller, Brannon Braga

Rating TV-PG

Where To Watch Paramount+

Alien (1979)

Alien is a sci-fi horror-thriller by director Ridley Scott that follows the crew of a spaceship known as the Nostromo. After the staff of the merchant's vessel perceives an unknown transmission as a distress call, its landing on the source moon finds one of the crew members attacked by a mysterious lifeform, and they soon realize that its life cycle has merely begun.

Director Ridley Scott

Release Date June 22, 1979

Studio(s) 20th Century Fox

Distributor(s) 20th Century Fox

Writers Dan O'Bannon

Cast John Hurt, Sigourney Weaver, Yaphet Kotto, Veronica Cartwright, Tom Skerritt, Ian Holm, Harry Dean Stanton

Runtime 117 minutes

Genres Sci-Fi, Thriller, Horror

Franchise(s) Alien

Sequel(s) Alien: Covenant, Aliens, Prometheus, Alien Resurrection, Alien 3

Budget $11 million

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Star Trek: Voyager's producers decided to make Chakotay's Native American background a key part of the character's personality.To get a better understanding of Native American heritage, the Voyager producers enlisted writer and journalist Jamake Highwater, a nationally recognized Native American authority who wrote books and produced TV series about his supposed heritage.

Chakotay / tʃ ə ˈ k oʊ t eɪ / is a fictional character who appears in each of the seven seasons of the American science fiction television series Star Trek: Voyager.Portrayed by Robert Beltran, he was First Officer aboard the Starfleet starship USS Voyager, and later promoted to Captain in command of the USS Protostar in Star Trek: Prodigy.The character was suggested at an early stage of ...

Captain Chakotay was a 24th century Human male of Native American descent who served as a Starfleet officer before joining the Maquis. After his ship, the Val Jean, was transported and subsequently destroyed in the Delta Quadrant, he joined the crew of the starship USS Voyager as its first officer under Captain Kathryn Janeway during their seven-year journey back to Earth. (VOY: "Caretaker ...

Indian Country Today reports that Highwater was first outed in 1984. Despite being called out as a fake Native American in the mid-1980s, Highwater was still somehow able to get a job on Star Trek ...

The scenes thus not only establish a clear contrast to the program's otherwise "rational" storylines, but they also employ, again, well-worn imagery to evoke romantic stereotypes of the "Indian." Although Star Trek: Voyager hence makes an explicit effort to draw a more nuanced picture of Native American spirituality, the program is ...

Jamake Highwater (born Jackie Marks, also known as Jay or J Marks; 14 February 1931 - June 3, 2001) was an American writer and journalist of Eastern European Jewish ancestry who mispresented himself as Cherokee.. In the late 1960s, Marks assumed a pretendian identity, claiming to be Cherokee, and used the name "Jamake Highwater" for his writings. As Highwater, he wrote and published more ...

Khan Noonien Singh is a fictional character in the Star Trek science fiction franchise, who first appeared as the main antagonist in the Star Trek: The Original Series episode "Space Seed" (1967), and was portrayed by Ricardo Montalbán, who reprised his role in the 1982 film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.In the 2013 film Star Trek Into Darkness, he is portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch.

Chakotay's tribe was a group of Native Americans who occupied a planetary colony in the Cardassian Demilitarized Zone. Though the origins of their heritage was lost for centuries, it was eventually confirmed they partially descended from the ancient Rubber Tree People. The tribe was descended from the ancient Rubber Tree People of the Central American jungle. According to ancient myth, the Sky ...

Cathexis: Directed by Kim Friedman. With Kate Mulgrew, Robert Beltran, Roxann Dawson, Jennifer Lien. An encounter with a peculiar nebula suddenly leaves Chakotay brain dead and unconscious. The crew is left with a mysterious but powerful force of energy onboard that can take over the minds of the crew members.

Nightingale: Directed by LeVar Burton. With Kate Mulgrew, Robert Beltran, Roxann Dawson, Robert Duncan McNeill. When the Delta Flyer comes to the aid of a medical transport, Harry Kim gets his first command.

October 25th, 2021. Paramount. Chakotay was a first in many ways for Star Trek. He was an officer who had left the service, only to return when the situation demands. He was to have touched the ...

With a plethora of new 'Star Trek' shows, a return to the Delta Quadrant was inevitable. And we have that return in the form of the all-ages CGI series Star Trek: Prodigy. Set after the events of Star Trek: Voyager (and, indeed, Star Trek: Nemesis) Prodigy sees the return of the Delta Quadrant and a few familiar faces from its past as well.

Star Trek: Voyager: Created by Rick Berman, Michael Piller, Jeri Taylor. With Kate Mulgrew, Robert Beltran, Roxann Dawson, Robert Duncan McNeill. Pulled to the far side of the galaxy, where the Federation is seventy-five years away at maximum warp speed, a Starfleet ship must cooperate with Maquis rebels to find a way home.

An expanded version of my Indian Comics Irregular essay Star Trek Voyager: Chakotay:. On UPN's Star Trek: Voyager, Robert Beltran played Chakotay, a Native American who attended Starfleet Academy before joining the rebel Maquis. The standard view is that Chakotay, the first continuing Native character in a Trek series, was an uplifting role model.

(A Vision of the Future - Star Trek: Voyager, p.199) In an interview with Robert Fletcher - published as part one of "The Star Trek Costumes", in the February 1980 edition of Fantastic Films - the Shamin priests seen in Star Trek: The Motion Picture were described as "like the society of America's western Indian civilizations", despite no ...

Star Trek: Voyager is an American science fiction television series created by Rick Berman, Michael Piller and Jeri Taylor.It originally aired from January 16, 1995, to May 23, 2001, on UPN, with 172 episodes over seven seasons.It is the fifth series in the Star Trek franchise. Set in the 24th century, when Earth is part of a United Federation of Planets, it follows the adventures of the ...

In Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, there is a ship commanded by an Indian captain, the U.S.S. Yorktown. His name is Captain Joel Randolph. His ship has been disabled when it encountered the alien probe. He talks about the solar sail they are crafting and the high hopes they have for it.

Three episodes cover the whole range of Star Trek 's representation of Native Americans from the earliest instance in Star Trek: The Original Series to Star Trek: Voyager 's recurring Native American character, Commander Chakotay. First, in TOS 'The Paradise Syndrome' (S3, Ep3), Enterprise arrives on an alien planet, where an accident ...

Chakotay is often criticized for the inaccuracy of his character's Native American background and tradition. In our world, this is because the writers were getting notes on Indian culture from a charlatan who made a lot of money lying to people about being a Native American. Chakotay's fake tribe, the Anurabi, are from the jungles of Latin ...

PBS even adapted his book, The Primal Mind: Vision and Reality in Indian America, as the basis of a documentary about Native American culture, The Primal Mind (1984). ... According to A Vision of the Future, an analysis of Star Trek: Voyager by Stephen Edward Poe, notes that Chakotay was variously a Sioux, a Hopi, and a Native American with no ...