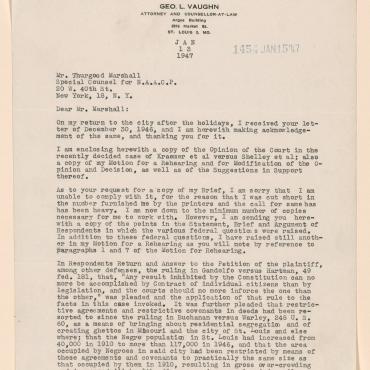

Freedom Rides

May 4, 1961 to December 16, 1961

During the spring of 1961, student activists from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) launched the Freedom Rides to challenge segregation on interstate buses and bus terminals. Traveling on buses from Washington, D.C., to Jackson, Mississippi, the riders met violent opposition in the Deep South, garnering extensive media attention and eventually forcing federal intervention from John F. Kennedy ’s administration. Although the campaign succeeded in securing an Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) ban on segregation in all facilities under their jurisdiction, the Freedom Rides fueled existing tensions between student activists and Martin Luther King, Jr., who publicly supported the riders, but did not participate in the campaign.

The Freedom Rides were first conceived in 1947 when CORE and the Fellowship of Reconciliation organized an interracial bus ride across state lines to test a Supreme Court decision that declared segregation on interstate buses unconstitutional. Called the Journey of Reconciliation, the ride challenged bus segregation in the upper parts of the South, avoiding the more dangerous Deep South. The lack of confrontation, however, resulted in little media attention and failed to realize CORE’s goals for the rides. Fourteen years later, in a new national context of sit-ins , boycotts, and the emergence of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Freedom Rides were able to harness enough national attention to force federal enforcement and policy changes.

Following an earlier ruling, Morgan v. Virginia (1946), that made segregation in interstate transportation illegal, in 1960 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Boynton v. Virginia that segregation in the facilities provided for interstate travelers, such as bus terminals, restaurants, and restrooms, was also unconstitutional. Prior to the 1960 decision, two students, John Lewis and Bernard Lafayette , integrated their bus ride home from college in Nashville, Tennessee, by sitting at the front of a bus and refusing to move. After this first ride, they saw CORE’s announcement recruiting volunteers to participate in a Freedom Ride, a longer bus trip through the South to test the enforcement of Boynton . Lafayette’s parents would not permit him to participate, but Lewis joined 12 other activists to form an interracial group that underwent extensive training in nonviolent direct action before launching the ride.

On 4 May 1961, the freedom riders left Washington, D.C., in two buses and headed to New Orleans. Although they faced resistance and arrests in Virginia, it was not until the riders arrived in Rock Hill, South Carolina, that they encountered violence. The beating of Lewis and another rider, coupled with the arrest of one participant for using a whites-only restroom, attracted widespread media coverage. In the days following the incident, the riders met King and other civil rights leaders in Atlanta for dinner. During this meeting, King whispered prophetically to Jet reporter Simeon Booker, who was covering the story, “You will never make it through Alabama” (Lewis, 140).

The ride continued to Anniston, Alabama, where, on 14 May, riders were met by a violent mob of over 100 people. Before the buses’ arrival, Anniston local authorities had given permission to the Ku Klux Klan to strike against the freedom riders without fear of arrest. As the first bus pulled up, the driver yelled outside, “Well, boys, here they are. I brought you some niggers and nigger-lovers” (Arsenault, 143). One of the buses was firebombed, and its fleeing passengers were forced into the angry white mob. The violence continued at the Birmingham terminal where Eugene “Bull” Connor ’s police force offered no protection. Although the violence garnered national media attention, the series of attacks prompted James Farmer of CORE to end the campaign. The riders flew to New Orleans, bringing to an end the first Freedom Ride of the 1960s.

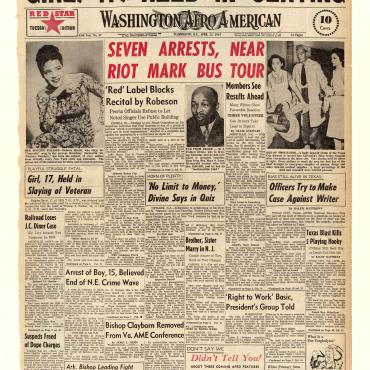

The decision to end the ride frustrated student activists, such as Diane Nash , who argued in a phone conversation with Farmer: “We can’t let them stop us with violence. If we do, the movement is dead” (Ross, 177). Under the auspices and organizational support of SNCC, the Freedom Rides continued. SNCC mentors were wary of this decision, including King, who had declined to join the rides when asked by Nash and Rodney Powell. Farmer continued to express his reservations, questioning whether continuing the trip was “suicide” (Lewis, 144). With fractured support, the organizers had a difficult time securing financial resources. Nevertheless, on 17 May 1961, seven men and three women rode from Nashville to Birmingham to resume the Freedom Rides. Just before reaching Birmingham, the bus was pulled over and directed to the Birmingham station, where all of the riders were arrested for defying segregation laws. The arrests, coupled with the difficulty of finding a bus driver and other logistical challenges, left the riders stranded in the city for several days.

Federal intervention began to take place behind the scenes as Attorney General Robert Kennedy called the Greyhound Company and demanded that it find a driver. Seeking to diffuse the dangerous situation, John Seigenthaler, a Department of Justice representative accompanying the freedom riders, met with a reluctant Alabama Governor John Patterson . Seigenthaler’s maneuver resulted in the bus’s departure for Montgomery with a full police escort the next morning.

At the Montgomery city line, as agreed, the state troopers left the buses, but the local police that had been ordered to meet the freedom riders in Montgomery never appeared. Unprotected when they entered the terminal, riders were beaten so severely by a white mob that some sustained permanent injuries. When the police finally arrived, they served the riders with an injunction barring them from continuing the Freedom Ride in Alabama.

During this time, King was on a speaking tour in Chicago. Upon learning of the violence, he returned to Montgomery, where he staged a rally at Ralph Abernathy ’s First Baptist Church. In his speech, King blamed Governor Patterson for “aiding and abetting the forces of violence” and called for federal intervention, declaring that “the federal government must not stand idly by while bloodthirsty mobs beat nonviolent students with impunity” (King, 21 May 1961). As King spoke, a threatening white mob gathered outside. From inside the church, King called Attorney General Kennedy, who assured him that the federal government would protect those inside the church. Kennedy swiftly mobilized federal marshals who used tear gas to keep the mob at bay. Federal marshals were later replaced by the Alabama National Guard, who escorted people out of the church at dawn.

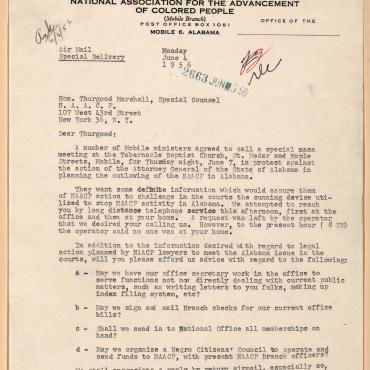

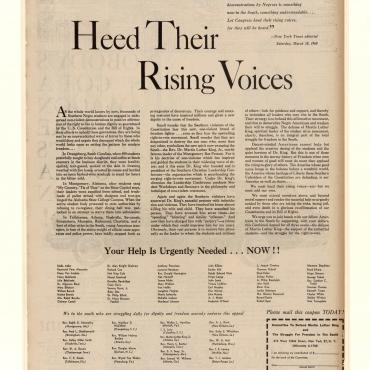

As the violence and federal intervention propelled the freedom riders to national prominence, King became one of the major spokesmen for the rides. Some activists, however, began to criticize King for his willingness to offer only moral and financial support but not his physical presence on the rides. In a telegram to King the president of the Union County National Association for the Advancement of Colored People branch in North Carolina, Robert F. Williams , urged him to “lead the way by example.… If you lack the courage, remove yourself from the vanguard” ( Papers 7:241–242 ). In response to Nash’s direct request that King join the rides, King replied that he was on probation and could not afford another arrest, a response many of the students found unacceptable.

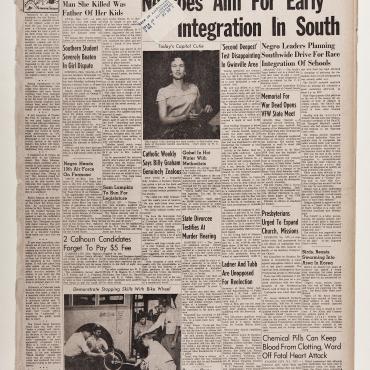

On 29 May 1961, the Kennedy administration announced that it had directed the ICC to ban segregation in all facilities under its jurisdiction, but the rides continued. Students from all over the country purchased bus tickets to the South and crowded into jails in Jackson, Mississippi. With the participation of northern students came even more press coverage. On 1 November 1961, the ICC ruling that segregation on interstate buses and facilities was illegal took effect.

Although King’s involvement in the Freedom Rides waned after the federal intervention, the legacy of the rides remained with him. He, and all others involved in the campaign, saw how provoking white southern violence through nonviolent confrontations could attract national attention and force federal action. The Freedom Rides also exposed tactical and leadership rifts between King and more militant student activists, which continued until King’s death in 1968.

Arsenault, Freedom Riders , 2006.

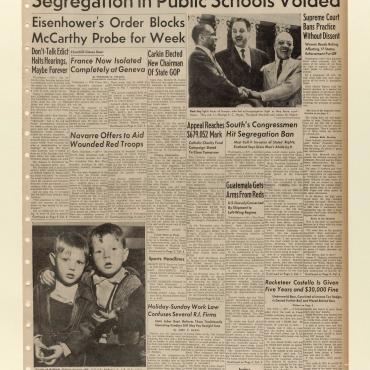

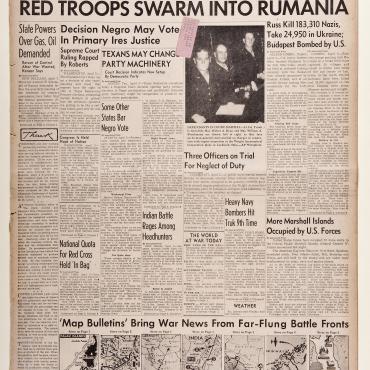

“Bi-Racial Group Cancels Bus Trip,” New York Times , 16 May 1961.

Carson, In Struggle , 1981.

Garrow, Bearing the Cross , 1986.

King, Statement Delivered at Freedom Riders Rally at First Baptist Church, 21 May 1961, MMFR .

Lewis, Walking with the Wind , 1998.

Peck, Freedom Ride , 1962.

Ross, Witnessing and Testifying , 2003.

Williams to King, 31 May 1961, in Papers 7:241–242 .

Freedom Riders end racial segregation in Southern U.S. public transit, 1961

Wave of campaigns, time period, location city/state/province, location description.

- An Example of Paradox of Repression

- Included Participation by More Than One Social Class

Methods in 1st segment

- Did this in locations where violent resistance not encountered

Methods in 2nd segment

Methods in 3rd segment, methods in 4th segment, methods in 5th segment, methods in 6th segment, segment length, notes on methods, external allies, involvement of social elites, nonviolent responses of opponent, campaigner violence, repressive violence, classification, group characterization, groups in 1st segment, success in achieving specific demands/goals, total points, notes on outcomes, database narrative.

In 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) conducted a “Journey of Reconciliation” to direct attention toward racial segregation in public transportation in the Southern U.S.A. Although this initial freedom ride campaign was not regarded as a great success during its time, it inspired the 1961 Freedom Rides that fueled the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

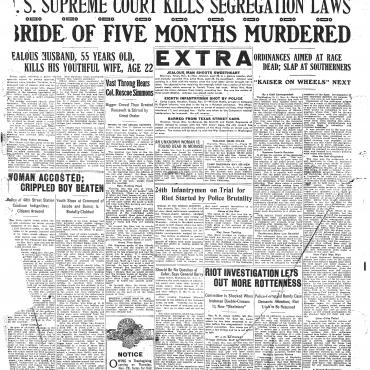

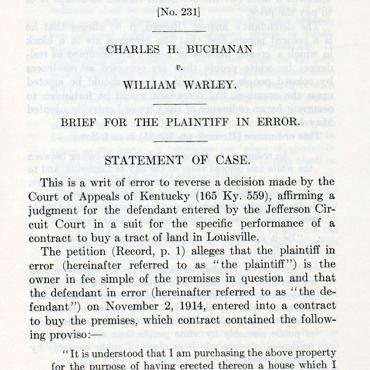

CORE’s strategy was to take advantage of two new Supreme Court rulings. Boynton vs. Virginia was a court case from 1958 involving a Howard University law student who was arrested for attempting to desegregate the whites-only Trailways bus terminal restaurant in Richmond, Virginia. The Supreme Court overturned Boynton’s conviction and ruled that state laws mandating segregation in waiting rooms, lunch counters, and restroom facilities for interstate passengers were unconstitutional. The ruling also extended an earlier case, Morgan vs. Commonwealth of Virginia, which ruled that legally enforcing segregation on interstate buses and trains was unconstitutional.

Despite these two Supreme Court rulings, in 1961 African Americans were still harassed on interstate buses and facilities were segregated. President John F. Kennedy had just entered the White House and, even though he was preoccupied by the Cold War with the Soviet Union, CORE expected that he could be pressured by nonviolent direct action to enforce the civil rights of African Americans.

Led by CORE Director James Farmer, the first team of thirteen volunteer Freedom Riders left Washington, D.C., on 4 May 1961, heading south. Most of the riders were in their 40s and 50s. Before leaving they got intensive training including role-plays. As an interracial group their intention was to sit wherever they wanted on buses and trains as well as to demand unrestricted access to terminal restaurants and waiting rooms.

The Riders encountered little resistance in Virginia, but some were arrested in North Carolina. They met physical violence in Rock Hill, South Carolina, as well as arrests, and proceeded on to Georgia.

Police in Birmingham, Alabama decided to use violence to stop the campaign when it reached their state and chose Anniston for their first battle. They agreed that the Ku Klux Klan (a white terrorist organization) would be encouraged to attack the activist team. On 14 May, Mother’s Day, a mob of Ku Klux Klansmen attacked the first of the two buses that carried Freedom Riders, slashing its tires, following up by firebombing the bus in the rear. The mob held the front bus door shut, apparently hoping to burn the riders to death, but the Riders were able to escape. As the riders exited the bus they were viciously beaten. Highway patrolmen then appeared to prevent the Riders from being killed.

That night in Birmingham, the hospitalized Riders from the first bus narrowly escaped renewed attacks by a mob.

The second bus, on reaching its stop in Anniston, was boarded by eight Klansmen who beat the Freedom Riders and left them semi-conscious. The bus continued on to Birmingham, where it was again attacked at the bus terminal by a mob with baseball bats, iron pipes and bicycle chains. One member of the mob was an FBI informant.

When US Attorney General Robert Kennedy was informed of the bus burning and beatings, he urged CORE to exercise restraint. Refusing the advice, the Freedom Riders decided to continue on to Montgomery where another mob waited for them; at that point, however, bus drivers refused to drive them anywhere.

In Nashville, Tennessee, where a major black student-led sit-in campaign had previously achieved victory (see “Nashville students sit-in for U.S. civil rights, 1960”), leader Diane Nash organized fellow members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to continue the Freedom Ride that was stalled in Birmingham. A new set of ten Riders took the bus from Nashville to Birmingham where they were promptly arrested and jailed by Police commissioner Bull Connor.

Despite howling mobs around the Birmingham bus station, additional SNCC members were able to get on a bus on May 20 and head toward Montgomery at 90 miles an hour accompanied by the Alabama Highway Patrol. Once in Montgomery the Highway Patrol left them and they were beaten with baseball bats and iron pipes by a white mob. Ambulances were called but refused to take the wounded to the hospital. The riders were rescued by local blacks.

Late that night a mob of thousands of whites surrounded a black church in Montgomery where the Freedom Riders and locals were holding a meeting. As the mob began to attack the church, the black citizens, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., responded with prayer and hymns. King attempted to address the white mob but returned to the church after being showered with bricks.

In the meantime, more volunteers arrived in Montgomery from CORE and SNCC to continue the rides. Faced with the campaign’s continuing against the Kennedys’ advice, the U.S. administration apparently felt forced to intervene, gaining promises from the governors of Alabama and Mississippi to reduce the level of mob violence, although the agreement allowed the governors to continue to arrest the Freedom Riders – in violation of federal law.

On 24 May the Freedom Riders continued on toward Jackson, Mississippi, where they were arrested when they tried to use the white-only facilities in the bus terminal. Some Freedom Riders left behind in Montgomery were arrested for violating local segregation laws.

The Kennedys again asked for a “cooling off period” and showed no intention of enforcing the Supreme Court’s view of black rights. The organizations now backing the campaign—CORE, SNCC, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)—decided to defy the Kennedys and continue the campaign throughout the summer if need be. During June, July, August, September more than 60 Freedom Rides traveled across the South, most of them ending in Mississippi.

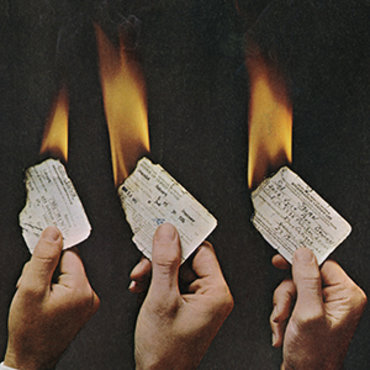

The riders who got to Jackson were arrested -- more than 300 in total (out of an estimated total of 450 riders in all). Most of the activists were male, under 30, and about evenly divided between black and white. Once arrested most riders staged a “jail-in” rather than use a provision for bail or fines; their strategy was to fill the jails and state prisons, stressing the treasury of the state of Mississippi.

The white-owned national mass media mostly presented a negative image of the Riders and editorials condemned the Freedom Rides through the long, hot summer. Despite this, there was increasing criticism expressed internationally toward the federal unwillingness to enforce the law. The expanding campaign of direct action increased the pressure on the states and the federal government.

As U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy was the chief law enforcement official in the nation, he eventually found a legal mechanism he could use to end the campaign, pressing the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to enforce integration.

The new ICC policy took effect 1 November. Black passengers could sit anywhere on buses, trains, or terminal lunch counters. “White” and “colored” signs were removed from the toilets and drinking fountains. African Americans living in states still dominated by the Ku Klux Klan and White Citizens Councils began to envision major change and prepare for the campaigns of the future. They had seen that, regardless of the intimidation and violence directed towards the Freedom Riders, the activist teams had all continued to defy segregation with a nonviolent discipline. The riders sang songs, made signs, and refused to move even though facing arrest, assault, and possible death.

Three years after the first Freedom Ride, the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, outlawing segregation in public facilities in all parts of the United States.

The freedom rides were influenced by a 1947 CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) freedom ride known as “The Journey of Reconciliation.” (1)

Additional Notes

Name of researcher, and date dd/mm/yyyy.

- Corrections

Freedom Rides of 1961: Challenging Segregation in the American South

The Freedom Rides of 1961 was a nonviolent protest campaign that challenged the segregation of interstate travel facilities by riding interstate buses through the Deep South.

Despite the US Supreme Court decision that deemed segregation in specific facilities for interstate travelers unconstitutional in 1960, segregation laws in the Deep South were still strongly enforced. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized the Freedom Rides of 1961 to challenge the federal government to take a stand and intervene as Jim Crow laws still ruled over the South.

Organizing the Freedom Rides of 1961

An initial attempt of the Freedom Rides was made by CORE in 1947 after the 1946 Morgan v. Virginia case deemed segregation in interstate transportation unconstitutional. However, the campaign, known as the Journey of Reconciliation, was not very successful as it did not receive the national media attention it needed to support the protest’s goals. In the midst of various Civil Rights Movement protests, CORE decided it was time to launch the new Freedom Rides of 1961 campaign.

The Freedom Riders planned to leave from Washington DC on May 4, 1961 to take a 13-day interstate bus trip down through the southern states. The goal was to challenge the segregation of the interstate bus terminal facilities and see if the southern states would integrate while they visited major cities throughout the South. The Riders were divided into two groups: one group rode on a Trailways bus, while the other rode on a Greyhound bus.

Before the Riders left for their trip, they participated in training that involved role-play so they were prepared for the type of behaviors they would face when encountering angry segregationists. An itinerary was created for the trip with New Orleans, Louisiana as the final destination. Once the Riders reached New Orleans, they planned on holding a rally that would also celebrate the seventh anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Who Were the Freedom Riders?

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

The Freedom Riders was an interracial group that consisted of student and civil rights activist volunteers. The original group of the 1961 Freedom Riders included 13 civil rights activists from varying backgrounds. James Farmer was the director of CORE and led the first group of Freedom Riders. Some of the members included John Lewis, James Peck, Genevieve Hughes Houghton, and Mae Francis Moultrie. More riders joined throughout the campaign.

James Peck was the only member of the original group who also participated in the Journey of Reconciliation campaign in 1947, including civil rights leader Bayard Rustin . As the Freedom Rides of 1961 began to gain national attention, more activists became inspired to join in the campaign. Many activists were students who sacrificed graduating from college in order to participate.

Freedom Riders Meet Violence in the Deep South

The first few stops in Richmond, Virginia and Greensboro, North Carolina went well for the Riders. Some of the Riders had hopes that residents in the areas they stopped would integrate facilities while they were there, and some did. However, once they reached Rock Hill, South Carolina and traveled further south, violence became a common welcoming from angry white mobs.

While stopped at the Greyhound bus terminal in Rock Hill, John Lewis attempted to sit in a “whites-only” waiting room and was beaten by a mob. Martin Luther King met with the Riders during their journey in Atlanta, Georgia. He allegedly told one of the reporters traveling with the Riders, Simeon Booker, they would “ never make it through Alabama .”

The statement made by King held some truth. The Greyhound bus was met by an angry white mob upon their arrival in Anniston, Alabama on May 14, 1961. Once the bus came to a stop, the mob attacked the bus and slashed the tires. When the bus tried to drive away, a car zig-zagged in front of it to try and slow them down until the bus was forced to stop due to the flat tires.

The mob approached the bus again and began breaking the windows before throwing a firebomb in from the back window. The bus quickly became engulfed in flames with the passengers still inside, choking on the thick smoke. Once the Riders could burst through the front doors, they fled out of the bus only to be met with beatings by the mob. A state trooper eventually arrived, firing a single shot in the air to disperse the crowd.

Brutality Continues in Birmingham, Alabama

The Trailways bus managed to make it to Birmingham, Alabama, which was expected to be one of the most dangerous stops on the trip. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) of Alabama put out an announcement about the Freedom Rides of 1961 and managed to rally hundreds of segregationists for the Riders’ arrival. By this time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation was well aware of the violence that had taken place in Anniston but did not intervene.

When the Trailways bus stopped at the Birmingham Trailways Station on May 15, a massive brawl broke out. The Riders were severely beaten, and many were hospitalized. When they were released from the hospital the following day, they could not find a bus driver willing to drive them to Montgomery and were stranded. The violence in Alabama was covered by national media outlets, forcing federal authorities to intervene. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy called on his special assistant, John Seigenthaler, to travel to Birmingham to help the Riders get out of Alabama.

Seigenthaler coordinated with the airlines to allow the Riders to quickly board a flight to New Orleans. The Riders thought that the Freedom Rides of 1961 were over as they were unable to reach Montgomery, Alabama and Jackson, Mississippi. However, student activists from Nashville and surrounding areas were following the events of the Freedom Riders and decided to join the campaign to complete the trip.

Federal & State Officials Failed to Support the Freedom Riders

The Kennedy administration and federal officials were heavily criticized for their lack of enforcement of the new federal laws in the Deep South . John F. Kennedy was more focused on the Cold War at the time and found the Civil Rights Movement to be an afterthought. The only reason the federal government got involved in the Freedom Rides of 1961 was due to the news coverage that led the events of the rides to gain attention internationally. The lack of federal law enforcement became an embarrassment for John F. Kennedy and his administration.

The Alabama Governor, John Peterson, failed to take action when violence first erupted when the Greyhound bus was attacked in Anniston. The FBI’s director, J. Edgar Hoover, refused to allow agents to get involved and ordered them only to observe the events that took place during the Freedom Rides. He was fully aware of the KKK riot that was waiting for the Freedom Riders in Birmingham, Alabama and did not relay this information to Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Hoover had no desire to use FBI resources to help de-escalate the riots in the Deep South.

Robert F. Kennedy was responsible for sending special assistant John Seigenthaler to help the Freedom Riders get out of Birmingham and to New Orleans. He also proposed the ban of segregation on interstate buses and facilities in September, which would take effect two months later.

Second Wave of the 1961 Freedom Rides

Student civil rights activists in Nashville, Tennessee refused to let the violent segregationist mobs immobilize the Freedom Rides of 1961. Diane Nash and other university students organized to send reinforcements to Montgomery to finish the Freedom Rides of 1961. Nash was the coordinator of the group, and ten volunteers were selected.

Seigenthaler received word that more Freedom Riders were on their way to Alabama. He contacted Nash to convince her to call off the campaign and warned her of the dangers the Riders would face upon their arrival. Nash responded by telling Seigenthaler they were aware of the consequences and had signed their last will and testament before departing.

The Nashville Freedom Riders’ trip ended when they were immediately arrested upon arrival in Jackson, Mississippi. Several reinforcements of Riders followed, who were also arrested and sent to the Parchman State Penitentiary . Despite the arrests, activists who were inspired by the original Riders and those who left out of Nashville decided to follow their lead. Some of the Riders saw the arrests as an opportunity to flood the jails in Mississippi and put a strain on the state’s resources needed to hold all of the Riders.

Successes of the Freedom Rides of 1961

The Freedom Rides of 1961 was one of the most successful nonviolent protest campaigns of the Civil Rights Movement. The Freedom Riders were able to get the attention of national media outlets and gain further support for the movement. The Rides forced the Kennedy administration to acknowledge the violence that civil rights activists were facing in the Deep South. Other countries were appalled to see that the US government was failing to enforce the policies that officials had implemented.

The Freedom Rides of 1961 resulted in the ban of segregation laws in interstate travel facilities, including buses, restrooms, water fountains, and lunch counters. The Interstate Commerce Commission officially banned segregation of interstate travel facilities within their jurisdiction on November 1, 1961. This was a major stepping stone in the Civil Rights Movement, as the Freedom Rides took place just three years before segregation would be outlawed in all public facilities upon the implementation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Cold War: Sociocultural Effects in the United States

By Amy Hayes BA History w/ English minor Amy is a contributing writer with a passion for historical research and the written word. She holds a BA in history from Old Dominion University with a concentration in English. Amy grew up in the historic state of Virginia and quickly became fascinated by the intricate details of how people, places, and things came to be. She specializes in topics on American history, Ancient and Medieval England, law, and the environment.

Frequently Read Together

Benefits & Rights: World War II’s Sociocultural Impact

Bayard Rustin: The Man Behind the Curtain of the Civil Rights Movement

Gee’s Bend Quilts: Objects of Cultural Identity in the American South

- Modern History

The 1961 Freedom Riders' fight against segregation in America

In 1961, a group of black and white civil rights activists rode buses throughout the American South to challenge segregation laws.

This brave act is known as the Freedom Rides. The Freedom Riders were met with violence and hatred, but they refused to back down.

Their courage helped bring about change and paved the way for future civil rights victories.

In 1946, the Supreme Court’s Morgan v. Virginia court decision ruled that segregated interstate bus travel was unconstitutional.

However, this decision was not enforced, and segregated travel continued unabated.

Then, following the arrest of Rosa Parks , the Montgomery Bus Boycott occurred in 1955-1956.

This successful boycott, which was led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. , resulted in the desegregation of Montgomery’s bus system.

Then, in 1960, another supreme court decision, called Boynton v. Virginia found that segregation in interstate bus terminals was also unconstitutional.

This decision should have put an end to segregated travel, but again, it was not enforced.

This created a problem for the civil rights movement because it now had to find a way to challenge segregation laws without breaking any laws.

The solution was the Freedom Rides.

Activists from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) decided to test the new law by riding buses through the American South.

They would start in Washington, D.C., and ride through Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.

The Freedom Riders would use both “white” and “colored” restrooms and lunch counters at bus terminals along the way.

The journey begins

The Freedom Rides began on the 4th of May, 1961, when thirteen protestors, seven black and six whites, boarded two Greyhound buses in Washington D.C.

They intended to arrive in New Orleans on May 17 to celebrate the anniversary of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education court ruling that found that segregated public schools were unconstitutional.

The start of the journey was relatively uneventful. They faced no problems as they drove through the states of Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia.

The first negative experience occurred on the 12th of May when they had stopped at a Greyhound bus terminal at Rock Hill, South Carolina.

Three of the riders were attacked for attempting to use the “whites only” restroom. Despite the violence, they continued on.

In Anniston

The Freedom Riders arrived in Alabama on May 14th. They were met with a large crowd of around 200 angry white people at the bus terminal in Anniston.

The crowd was armed with iron bars, clubs, and chains. Fearing for his passengers' safety, the driver chose to drive past the station, but the crowd followed.

The bus had to stop at a gas station about 6 miles outside of Anniston when the tires went flat.

The crowd attacked the bus, slashed its tires, and threw a fire bomb inside. The bomb exploded, and the riders had to escape through the windows as the mob outside beat them.

Fortunately, all passengers managed to escape before the bus burst into flames.

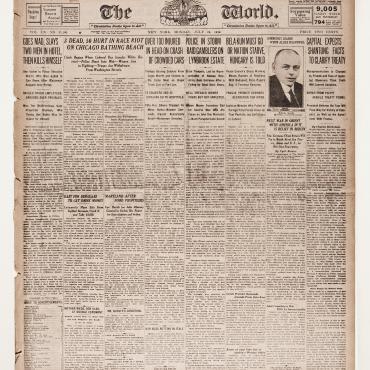

Photographs of the burning Greyhound bus, which had been taken by journalists who were following the protest, were published on front pages of newspapers around the country.

This drew national and international attention to their cause and created sympathy for their plight.

In Birmingham

The Freedom Riders arrived in Birmingham on 17th of May where they were again met by an angry mob.

The police did nothing to stop the violence, and the riders were beaten with clubs and chains. Some of them were hospitalised with serious injuries.

Despite the violence, all of the riders were arrested for defying segregation laws and “breaching the peace”.

The Freedom Riders spent two weeks in jail before the US Attorney General, Robert Kennedy, (brother of President John F. Kennedy) negotiated with the Governor of Alabama for their release.

Once freed, Kennedy also arranged for a police escort to protect their bus until they reached the city of Montgomery.

At the Montgomery bus station, the state troopers left the protestors, as local police were to take over the escort role for freedom riders.

However, the police never arrived. Without protection, the riders were attacked and beaten again. In response, President Kennedy sent 400 US Marshalls to provide protection for the final stage of their journey.

On the 24th of May 1961, the Freedom Riders arrived in Jackson, Mississippi. They were arrested for attempting to use white facilities and were charged for trespassing.

On the 29th of May 1961, the president announced a ban on segregation in all bus facilities.

The new ban took effect on the 1st of November 1961, which brought the Freedom Rides to an end.

Significance

The Freedom Rides helped bring about change by raising awareness of segregation laws in the American South.

They also showed that there was a need for better enforcement of these laws. The courage of the Freedom Riders inspired others to take a stand against segregation and helped pave the way for future civil rights victories.

One of the most famous of the Freedom Riders was John Lewis. He later went on to become a US Congressman and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011.

The Freedom Rides were an important moment in the American Civil Rights Movement.

They showed that there was a need for better enforcement of civil rights laws and inspired others to take a stand against segregation.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

- Earth and Environment

- Literature and the Arts

- Philosophy and Religion

- Plants and Animals

- Science and Technology

- Social Sciences and the Law

- Sports and Everyday Life

- Additional References

- Encyclopedias almanacs transcripts and maps

Freedom Rides

Initially organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1961, the Freedom Rides were trips made by interracial groups riding throughout the South on buses. Freedom Rides attempted to galvanize the U.S. Justice Department into enforcing federal desegregation laws in interstate travel, especially in bus and train terminals. White riders sat on the back of the bus, and black riders on the front, challenging long-standing southern racist transportation practices. Once at the terminal, white Freedom Riders proceeded to the "black" waiting room, while blacks attempted to use the facilities in the "white" waiting room.

Freedom Rides were a continuation of the student-led sit-in movement that was sparked in February 1, 1960, by four African-American college freshmen in Greensboro, North Carolina . When these students remained at a Wool-worth's lunch counter after being refused service, they inspired hundreds of similar nonviolent student demonstrations. Essentially, Freedom Rides took the tradition of sitins on the road.

The idea for the 1961 Freedom Rides was conceived by Tom Gaither, a black man, and Gordon Carvey, a white man, who were field secretaries of CORE. In light of the 1960 Boynton v. Virginia Supreme Court judgment that banned segregation in bus and train terminals, Gaither and Carvey decided that compliance with the law should be gauged. The two activists were also inspired by the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation. Motivated by another Supreme Court ruling, the Journey of Reconciliation was made by an interracial group of sixteen activists that traveled through the South to test Morgan v. Virginia , the 1946 federal case that resulted in the legal ban of segregation on interstate buses and trains. In the spirit of the Journey of Reconciliation, CORE began organizing and planning for the first Freedom Rides.

In early 1961, CORE, headed by its director and cofounder, James Farmer (1920 – 1999), began carefully selecting the thirteen original Freedom Riders . The chosen group comprised seven blacks and six whites, from college students to civil rights veterans, including a Journey of Reconciliation participant, the white activist James Peck. The journey for the riders began on May 4 from Washington D.C. to Atlanta, Georgia, on two buses. The plan was to continue through Alabama, Mississippi, and finally to New Orleans , Louisiana, on May 17 for a desegregation rally.

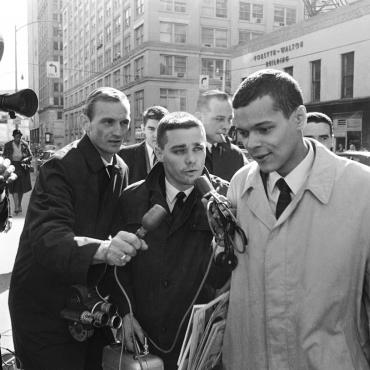

The first episode of violence occurred in Rock Hill, South Carolina , where twenty-one-year old John Lewis (b. 1940), the future Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) national chairman and U.S. congressman, and Albert Bigelow, an elderly white pacifist, were knocked unconscious by young white men. On May 14, 1961, the Freedom Riders boarded a Greyhound bus and a Trailways bus in Atlanta and headed for Birmingham, Alabama. The Trailways bus met six Ku Klux Klansmen in Anniston, Alabama, who threw the African Americans into seats in the back of the bus and hit two white riders on the head. In Birmingham, the bus encountered about twenty men with pipes who beat the riders when they disembarked.

In Anniston, the Greyhound bus faced two hundred angry whites. The bus retreated, but its tires were slashed. Once the tires blew out, a firebomb was tossed into the bus. The riders managed to escape before the bus went up in flames. The following day, another mob prevented the Freedom Riders from boarding a bus in Birmingham. With the help of John Seigenthaler, Attorney General Robert Kennedy's administrative assistant, the riders took a plane to New Orleans instead. The bus journey was continued under the leadership of SNCC, with the coordination efforts of SNCC members Diane Nash and John Lewis .

The Birmingham police commissioner, "Bull" Connor, used many tactics, including incarceration, to try to stop the students, but to no avail. Finally, the governor of Alabama, John Patterson, very reluctantly promised Robert Kennedy to protect the riders. As the new Freedom Riders left for Montgomery on May 20, 1961, it appeared that Governor Patterson had kept his word. However, by the time the bus arrived in Montgomery, all forms of police protection had disappeared. A mob of over one thousand whites viciously attacked the riders and Seigenthaler.

On May 24, twenty-seven determined Freedom Riders, with the protection of National Guardsmen, headed for Jackson, Mississippi. In Mississippi, they were arrested and jailed for sixty days. A new group of riders came to Jackson, and they were also arrested. Eventually, 328 Freedom Riders were incarcerated in Jackson. As per their philosophy, the riders chose jail over bail.

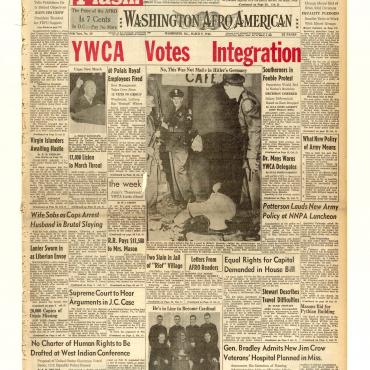

The Freedom Rides brought international attention to the southern struggle for desegregation, which put pressure on the authorities. Finally, on November 1, 1961, a huge victory for the Freedom Riders and all integrationists was won when the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) made segregated travel facilities illegal.

See also Civil Rights Movement , U.S. ; Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) ; Farmer, James ; Lewis, John ; Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

Bibliography

Farmer, James. Lay Bare the Heart: An Autobiography of the Civil Rights Movement . New York : Arbor House, 1985.

Hampton, Henry, and Steve Fayer. Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s through the 1980s. New York : Bantam Books, 1990.

Meier August, and Elliot Rudwick. CORE: A Study in the Civil Rights Movement, 1942 – 1968. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Peck, James. Freedom Ride. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962.

Zinn, Howard. SNCC: The New Abolitionists. Boston: Beacon Press, 1965.

jessica l. graham (2001)

Cite this article Pick a style below, and copy the text for your bibliography.

" Freedom Rides . " Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History . . Encyclopedia.com. 15 Apr. 2024 < https://www.encyclopedia.com > .

"Freedom Rides ." Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History . . Encyclopedia.com. (April 15, 2024). https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/freedom-rides

"Freedom Rides ." Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History . . Retrieved April 15, 2024 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/freedom-rides

Citation styles

Encyclopedia.com gives you the ability to cite reference entries and articles according to common styles from the Modern Language Association (MLA), The Chicago Manual of Style, and the American Psychological Association (APA).

Within the “Cite this article” tool, pick a style to see how all available information looks when formatted according to that style. Then, copy and paste the text into your bibliography or works cited list.

Because each style has its own formatting nuances that evolve over time and not all information is available for every reference entry or article, Encyclopedia.com cannot guarantee each citation it generates. Therefore, it’s best to use Encyclopedia.com citations as a starting point before checking the style against your school or publication’s requirements and the most-recent information available at these sites:

Modern Language Association

http://www.mla.org/style

The Chicago Manual of Style

http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html

American Psychological Association

http://apastyle.apa.org/

- Most online reference entries and articles do not have page numbers. Therefore, that information is unavailable for most Encyclopedia.com content. However, the date of retrieval is often important. Refer to each style’s convention regarding the best way to format page numbers and retrieval dates.

- In addition to the MLA, Chicago, and APA styles, your school, university, publication, or institution may have its own requirements for citations. Therefore, be sure to refer to those guidelines when editing your bibliography or works cited list.

More From encyclopedia.com

About this article, you might also like.

- Newton Girl Jailed in Mississippi with Eight Freedom Fighters

- Freedom, Intellectual

- Freedom Summer

- Mississippi Freedom Schools

- The Civil Rights Movement

- BOSMAJIAN, Haig

- Freedom of Assembly

NEARBY TERMS

Freedom Riders

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how and why various groups responded to calls for the expansion of civil rights from 1960 to 1980

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with The March on Birmingham Narrative; the Black Power Narrative; the Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” 1963 Primary Source; the Martin Luther King Jr., “I Have a Dream,” August 28, 1963 Primary Source; the Civil Disobedience across Time Lesson; the The Music of the Civil Rights Movement Lesson; and the Civil Rights DBQ Lesson to discuss the different aspects of the civil rights movement during the 1960s.

After World War II, the civil rights movement sought equal rights and integration for African Americans through a combination of federal action and local activism. One specific area the movement attempted to change was the segregation of interstate travel. In Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946), the Supreme Court had ruled that segregated seating on interstate buses was unconstitutional, but the ruling was largely ignored in southern states.

In 1960, the Supreme Court followed up on its earlier decision and ordered the integration of interstate buses and terminals. In 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which had been formed in 1942, appointed a new national director, James Farmer. Farmer’s idea for a freedom ride to desegregate interstate buses was inspired by the college students who had launched the recent spontaneous and nonviolent sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters, starting in Greensboro, North Carolina. These sit-ins had soon spread to 100 cities across the South. Farmer decided to have an interracial group ride the buses from Washington, DC, to New Orleans to commemorate the anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education case.

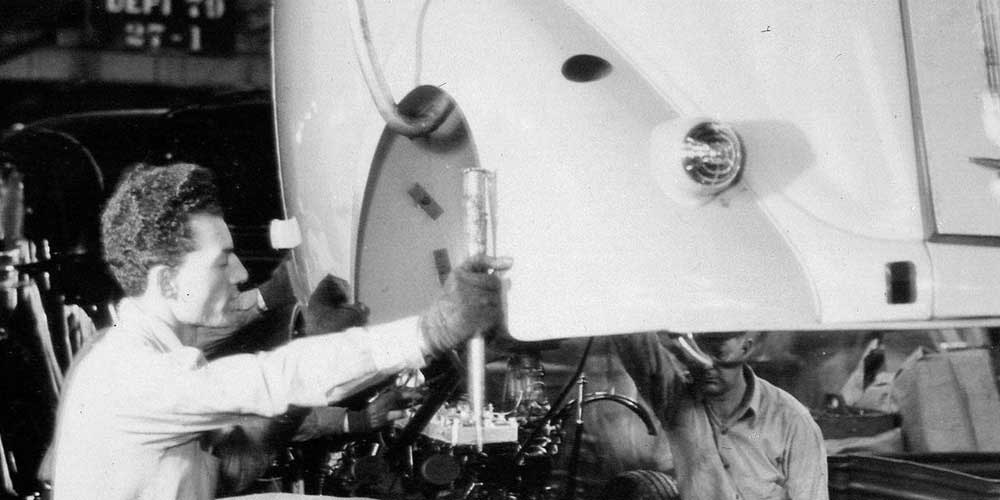

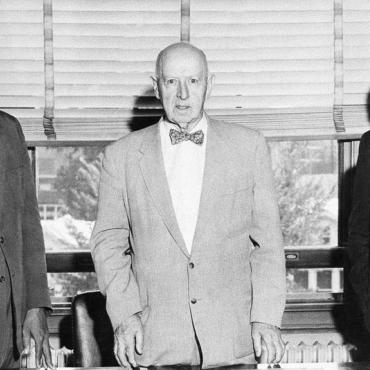

James Farmer was a leader in the civil rights movement and, in 1961, helped organize the first freedom ride.

Members of CORE sent letters to President Kennedy, his brother Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) director J. Edgar Hoover, the chair of the Interstate Commerce Commission, and the president of the Greyhound Corporation announcing their intentions to make the ride and hoping for protection. CORE decided to move forward despite receiving no response.

The 13 recruits underwent three days of intensive training in the philosophy of nonviolence, role playing the difficult situations they could expect to encounter. On May 4, 1961, six of the riders boarded a Greyhound bus and seven took a Trailways bus, planning to ride to New Orleans. The riders knew they would face racial epithets, violence, and possibly death. They hoped they had the courage to face the trial nonviolently in their fight for equality.

The riders challenged the segregated bus seating, with black participants riding in the “white” sections and riders of both races using segregated lunch counters and restrooms in the Virginia cities of Fredericksburg, Richmond, Farmville, and Lynchburg, but no one seemed to care. After they crossed into North Carolina, one of the black riders was arrested trying to get a shoeshine at a whites-only chair in Charlotte but was soon released. The group faced physical violence for the first time in Rock Hill, South Carolina: John Lewis, a black college student; Albert Bigelow, an older white activist; and Genevieve Hughes, a young white woman, were all assaulted before they were rushed to safety by a local black pastor. Two more riders were arrested and released in Winnsboro, and two riders had to interrupt the ride for other commitments, but four new riders joined.

On May 6, while the rides continued, the attorney general delivered a major civil rights address promising that the Kennedy administration would enforce civil rights laws. Though he seemed more concerned with America’s image abroad during the Cold War, he stated that the administration “will not stand by and be aloof.” The freedom rides presented an opportunity for the attorney general to fulfill that promise.

Attorney General Robert Kennedy was a supporter of enforcing federal civil rights laws. He spoke to CORE in 1963, outside the Justice Department in Washington, DC.

In Augusta and Atlanta, Georgia, the riders ate at desegregated lunch counters and sat in desegregated waiting rooms. They were discovering that different communities throughout several southern states had different racial mores. They met with Martin Luther King Jr., who shared intelligence he had about impending violence in Alabama. A Birmingham police sergeant, Tom Cook, and the public safety commissioner, Bull Connor, were in league with the local Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which was planning a violent reception for the riders in that city. Cook and Connor had agreed that the mob could beat the riders for about 15 minutes before they would send the police and make a show of restoring order. The FBI had informed the attorney general, but neither acted to protect the riders or even to inform them of what awaited them.

The Greyhound bus departed Atlanta on the morning of May 14. The first group reached a stop in Anniston, Alabama, where an angry mob of whites armed with guns, bats, and brass knuckles surrounded the bus. Two undercover Alabama Highway Patrol officers on the bus quickly locked the doors, but members of the crowd smashed its windows. The Anniston police temporarily restored order and the bus left, trailed by 30 to 40 cars that then surrounded it and forced it to stop. Suddenly, a member of the crowd hurled flaming rags into the bus, and it exploded into flames. The riders climbed out through windows and the doors, barely escaping with their lives. The mob assaulted them and used a baseball bat on the skull of a young black male, Hank Thomas, before an undercover officer fired his gun into the air and a fuel tank exploded, dispersing the crowd. The riders went to the hospital, where they were refused care and were driven in activists’ cars to Birmingham.

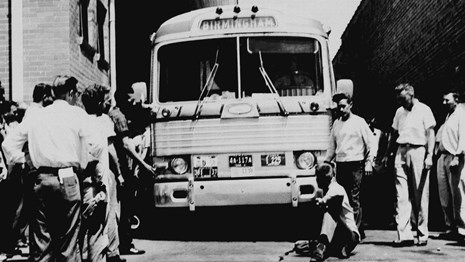

A Greyhound bus carrying freedom riders was firebombed by an angry mob while in Anniston, Alabama, in 1961. Forced to evacuate, the passengers were then assaulted. (credit: “Freedom Riders Bus Attack” by Federal Bureau of Investigation)

The riders on the Trailways bus were terrorized by KKK hoodlums who boarded in Atlanta. At first, the white supremacists merely taunted the riders with warnings about the violence that awaited them in Birmingham, but when the riders sat in the white section of the bus, horrific violence erupted. Two riders were punched in the face and knocked to the floor where they were repeatedly kicked and beaten into unconsciousness. Two other riders tried to intervene peacefully and suffered the same fate. They were dragged to the back of the bus and dumped there.

Bull Connor carried out his plan not to post officers at the Birmingham bus station, with the excuse that it was Mother’s Day. Consequently, another large mob awaited the riders and forced them off the bus and assaulted them. Riders Ike Reynolds and Charles Person were knocked down and bloodied by a series of vicious blows. An older white rider, Jim Peck, was struck in the head several times, opening a wound that required 53 stitches. Peck later told a reporter that he endured the violence courageously to “show that nonviolence can prevail over violence.” The police finally showed up after the allotted 15 minutes but made no arrests. Other riders escaped, and they all met at Reverend Fred Shuttleworth’s church.

Americans across the country learned about the violence as the images of burning buses and beaten riders were broadcast on television and printed in newspapers. President Kennedy was preparing for a foreign summit and wanted the freedom riders to stop causing controversy. Attorney General Kennedy tried to persuade the Alabama governor, John Patterson, to protect the riders but was frustrated in the attempt. Also exasperated by Greyhound’s unwillingness to provide a new bus for the riders, the attorney general sent one federal official, John Seigenthaler, to the riders in Birmingham.

The riders planned to go to Montgomery and continue to New Orleans but could not find a bus. They reluctantly settled on flying to their final destination but had to wait out bomb threats before quietly boarding a flight. Although the CORE freedom ride was over, Diane Nash, a black student at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, was inspired by their example. She coordinated additional freedom rides to desegregate interstate travel, which immediately proceeded from Nashville to Birmingham to finish the ride.

On Wednesday, the new group of riders were met at the Birmingham terminal by the police, who quickly arrested them. The riders went on a hunger strike in jail and were dumped on the side of the road more than 100 miles away in Tennessee before sunrise on Friday. However, they simply drove back to Birmingham, where they attempted to board a bus for Montgomery, but the terrified driver refused to let them on. The Kennedy administration negotiated a settlement in which the state police were to protect the bus bound for Montgomery.

The bus pulled into the Birmingham station, but the police cars disappeared. The freedom riders faced another horrendous scene: a crowd armed with bricks, pipes, baseball bats, and sticks yelling death threats. A young white man, Jim Zwerg, stepped off the bus first and was dragged down into the mob and knocked unconscious. Two female riders were pummeled, one by a woman swinging a purse and repeatedly hitting her in the head, the other by a man punching her repeatedly in the face.

Seigenthaler attempted to rescue the women by putting them into his car and driving away, but he was dragged from the car and knocked unconscious with a pipe and kicked in the ribs. A young black rider, William Barbee, was beaten into submission with a baseball bat and suffered permanent brain damage. A black bystander was even set afire after having kerosene thrown on him. The mayhem ended when a state police officer fired warning shots into the ceiling of the station. All the riders needed medical attention and were rushed to a local hospital.

That night, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Montgomery. Protected by a ring of federal marshals, King addressed a mass rally at First Baptist Church. He told the assembly, “Alabama will have to face the fact that we are determined to be free. The main thing I want to say to you is fear not, we’ve come too far to turn back . . . We are not afraid and we shall overcome.” Meanwhile, a white riot had erupted outside the church, and congregants spent the night inside.

A compromise was worked out two days later to get the riders out of Alabama and send them to Mississippi. A total of 27 freedom riders boarded the buses safely, accompanied by the Alabama National Guard, which, to the riders, defeated the purpose of challenging segregated seating on the bus. They were all arrested in Jackson in the bus depot for violating segregation statutes and were taken to jail. In the coming weeks, additional rides were made, but all suffered the same fate and more than 80 riders landed in jail under deplorable conditions.

Freedom riders Priscilla Stephens, from CORE, and Reverend Petty D. McKinney, from Nyack, New York, are shown after their arrest by the police in Tallahassee, Florida, in June 1961.

During the summer, the national media and many Americans lost interest in the freedom rides. A Gallup Poll in mid-June showed that a majority of Americans supported desegregated interstate travel and the use of federal marshals to enforce it. However, 64 percent of Americans disapproved of the rides after initial expressions of sympathy, and 61 percent thought civil rights should be achieved gradually instead of through direct action.

The civil rights movement was undeterred by such popular opinion. The 1960 Greensboro sit-ins and the 1961 freedom rides created a new momentum in the struggle for equal rights and freedom. Over the next few years, civil rights activists directly confronted segregation through nonviolent tactics at places like Birmingham and Selma to arouse the national conscience and to pressure the federal government for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Review Questions

1. The freedom rides in 1961 were most directly inspired by

- the lunch counter sit-ins started in Greensboro, North Carolina

- the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education

- the Supreme Court’s decision in Morgan v. Commonwealth

- the formation of the Congress of Racial Equality

2. Freedom riders from the early 1960s were best known for

- inciting violent protests against urban policing policies

- providing transportation to those participating in the Montgomery bus boycott

- boycotting travel on segregated buses across the South

- challenging segregated seating on interstate bus routes

3. Response to the freedom riders as they travelled throughout the South illustrated

- uniformly violent opposition to their actions

- varied racial attitudes and reactions on the part of southerners

- widespread indifference

- local support and public mobilization of the black community

4. The freedom riders encountered the most violent reactions to their methods in

- Lynchburg, Virginia

- Charlotte, North Carolina

- Atlanta, Georgia

- Birmingham, Alabama

5. The federal government’s response to the freedom rides was characterized generally by

- overwhelming support, including federal protection of the riders

- the full support of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and President John F. Kennedy, but not of Congress

- observation and information gathering but limited actual support

- official training in nonviolent tactics but little overt support

6. Compared with earlier tactics in the movement, in the early 1960s, new civil rights groups advocated greater emphasis on

- taking direct action

- working through the federal court system

- inciting violent revolution

- electing local officials sympathetic to their cause

7. The actions of the freedom riders most directly contributed to the

- Brown v. Board of Education decision

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Voting Rights Act of 1965

- election of President John F. Kennedy

Free Response Questions

- Explain how the freedom riders of the early 1960s drew upon the U.S. Constitution to justify their actions.

- Explain how the freedom rides of the early 1960s represented an evolution in the methods of the civil rights movement.

AP Practice Questions

1. The events in the image most directly led to

- a Supreme Court decision declaring segregation unconstitutional

- increased support for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- the development of the counterculture

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s becoming a civil rights leader

2. The event in the photograph contributed to which of the following?

- Debates over the role of government in American life

- An increase in public confidence in political institutions

- Domestic opposition to containment

- The abandonment of direct-action techniques to achieve civil rights

3. The event in the image was most directly shaped by

- the techniques and strategies of the anti-war movement

- desegregation of the armed forces

- a desire to achieve the promise of the Fourteenth Amendment

- Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society program

Primary Sources

James Farmer: letters to President John Kennedy. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum . 1961. https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/education/students/leaders-in-the-struggle-for-civil-rights/james-farmer

Suggested Resources

Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Rides: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-1963 . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Chafe, William. Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Dudziak, Mary L. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Graham, Hugh Davis. The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Lawson, Stephen F., and Charles Payne. Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968 . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998.

Salmond, John A. “My Mind Set on Freedom:” A History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968 . Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997.

Stern, Mark. Calculating Visions: Kennedy, Johnson, and Civil Rights . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

Follow the Path of the Freedom Riders in This Interactive Map

These civil rights activists showed true courage in telling the nation about the segregated South

Rebeca Coleman

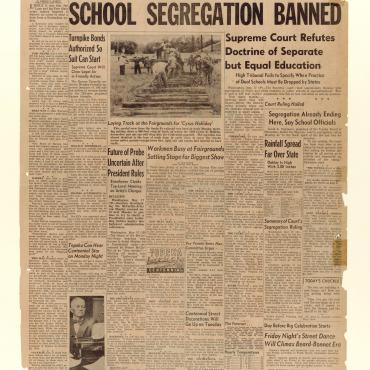

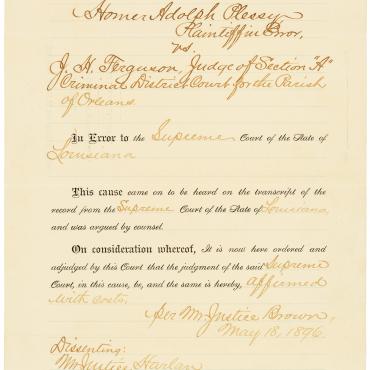

Even though the Civil War marked the end of slavery, African-Americans fought for equal rights throughout the century that followed. In the post-Reconstruction era, Jim Crow laws arose and the American South became a region of two segregated societies – whites and African Americans. Attempts to tear down this system in the courts bore little to no fruit. In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that “separate but equal” accommodations in public places were legal, enshrining a public policy that stayed on the books for decades.

The decision in Brown v. Board of Education that overturned Plessy marked one of the first major victories of the ever-growing Civil Rights Movement. That decision was followed by the Interstate Commerce Commission’s (ICC) decision to ban segregation on interstate bus travel and then in 1960, the Court ruled that the terminals and waiting areas themselves, including restaurants, could not be segregated. The ICC however, neglected to truly enforce its own rules and jurisdiction.

In 1961, a group of black and white individuals decided to take their frustration with the permanence of segregation, and the federal government’s disinterest in putting an end to the discrimination, to a further level. They decided to test the limits of Jim Crow laws by riding two buses together into the Deep South. Two groups, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) sponsored the Freedom Riders on their nonviolent protests of Southern segregation.

On May 4, 13 CORE and SNCC members embarked on their Freedom Ride through the American South with plans to engage in nonviolent protest and ensure that desegregation in public locales was being enforced. Many were seasoned protesters; some had even been arrested before. The overall goal was increasing awareness and decreasing segregation.

Their story, as told in the map above is one of resilience and perseverance. Some of the names are recognizable, including Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, and John Lewis, while some of the Riders themselves, such as Diane Nash and Henry Thomas, are lesser-known. Facing threats from the Ku Klux Klan and Bull Connor, these protestors played a crucial part in bringing the cruelties of the Jim Crow South to a national audience.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

- Annual Reports

- Evaluations

- MotorCities 25th Anniversary

- Job Opportunities

- Important Links

- Goodbye, John Dingell

- Speakers Bureau

- Grants & Programs

- Mini Grant Program

- Awards of Excellence

- Support MotorCities

- Individual Membership

- Organizational Membership

- Sponsorship

- Get Involved

- 2023 MotorCities Sponsors

- 2023 Membership List

- Find Your Road Trip

- Wayside Exhibit Program

- Things to See in Detroit

- MotorCities Automotive Themed Tours

- Arsenal of Democracy/Health

- Latest Stories

- Highway Signs

- MotorCities On The Road

- Many Voices, One Story

- Making Tracks

- Individual Profiles

- More Resources

- Junior Ranger

- Cool Auto Related Videos

- SW Detroit Auto Heritage

- 25th Anniversary

- NFL Draft Fans! Stuff to Do in the D

- The Freedom Rides of 1961

The Freedom Rides were conceived on the model of the “Journey of Reconciliation,” a demonstration that the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had organized in April 1947 to test the 1946 Supreme Court’s Morgan v. Virginia decision that banned segregated seating in interstate travel. The Journey of Reconciliation began on buses departing from Washington D.C. with passengers who planned to test the ruling in various cities in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. The national council of CORE unanimously decided in February 1961 to support another “Freedom Ride”: “Unlike the earlier journey, the Freedom Ride would go into the deep South, and it would integrate terminal accommodations as well as seating on buses.” The idea was, this time, to test the proper application of both 1946’s Morgan v. Virginia ruling and 1960’s Boynton v. Virginia ruling.

B. J. Hollars presents how the situation in many southern cities was inconsistent with both aforementioned rulings: “Despite two Supreme Court decisions that had ruled against segregation in public or interstate transportation vehicles and facilities, several southern cities still dictated where black people were allowed to sit on interstate buses and where they were allowed to eat within the travel facilities themselves. Whereas the Morgan decision confirmed that a state’s attempt to enforce segregation on interstate bus travel was in violation of the Interstate Commerce Clause, the Boynton decision went even further, confirming the illegality of segregated facilities within the bus terminals. Taken together, these rulings couldn’t have been clearer: segregation should not happen on interstate buses or in their terminals.”

In March and April 1961, CORE turned the Freedom Ride project of 1961 into a more concrete project: “In mid-March, CORE announced its plans for the ride and began soliciting volunteers. The participants had to commit themselves to nonviolence and agree to stay in jail if arrested rather than bail out and pay a fine. Late in April, the organization sent letters explaining the Freedom Ride to the President, the Attorney General, the Interstate

Commerce Commission, and the heads of Greyhound and the Trailways bus system.”

On May 4, 1961, an integrated group of 13 activists sent by CORE – including John Lewis – climbed on public buses in Washington, heading in the direction of New Orleans. They faced little opposition in Virginia and North Carolina, but they were more and more harassed and attacked as they drove into the South. They refused to acknowledge the “white-colored” signs of the waiting rooms and terminal restaurants and sat integrated in them as well as on buses.

It is well known that one of the Freedom Riders’ buses was set ablaze in Anniston, Alabama, and that a mob tried to kill the riders as they escaped the bus in flames. From the other bus, which reached Birmingham, the passengers were withdrawn and beaten nearly to death by Klansmen, while the Bull Connor-led police department kept its promise to refrain from taking any action for the first 15 minutes following the bus’s arrival in Birmingham. Persuaded to volunteer after having seen the reports of the Alabama attacks, more than 400 Americans made more than 60 Freedom Rides through the South in 1961, many of them also facing violence.

Scholars insist that the Freedom Riders were more diverse than a lot of Americans of the time generally considered them to be: they were far from being solely composed of “idealistic but naive white activists from the North”. In fact, “Black activists born and raised in the South accounted for six of the original 13 Freedom Riders and approximately 40 percent of the 400+ Riders who later joined the movement.” If southerners and northerners, women and men, older retirees and younger people, as well as secular and religious people were represented, a majority of Freedom Riders, though, were students or educated young people.

Through their work, the nation became aware that law enforcement officers in the South did not fulfill their duties, and that Jim Crow truly persisted in Southern transportation. The Freedom Riders were successful because their work was able to attract the interest of the Kennedy administration. As a consequence of their actions, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was petitioned on May 29 by Attorney General Robert Kennedy to issue clear regulations banning segregation in interstate travel: “He urged the ICC to prohibit interstate bus companies from segregating passengers on their vehicles and from providing or using any segregated terminal facilities. Kennedy also wanted the carriers to display notices of their nondiscrimination policy on buses and in depots and to report to the ICC all attempts to obstruct desegregation of their services, whether by individuals or by local and state governments.”

The persistence of the Freedom Riders put a form of pressure on the ICC to comply with the Attorney General’s demand. On September 22, 1961, the ICC commissioners finally issued a unanimous ruling outlawing discrimination in interstate bus transit, “endorsing virtually every point in the attorney general’s petition”; “The ICC order also required bus operators to report any attempts to interfere with the new regulations and provided fines of up to $500 for each violation. The obligation to report interference within 15 days of an incident pertained to governmental as well as individual violators, a provision that would prove crucial to enforcement in the months to come.” The ICC’s ruling would take effect from November 1, 1961.

Raymond Arsenault, the first historian to have written a book-length study on the Freedom Rides in 2006, suggested that “they have not attracted the attention that they deserve” from historians. He claims that the events of 1961 “would seem to be a likely choice as the pivot of a pivotal era in civil rights history,” since they were exactly in the midpoint between the 1954 Brown decision and the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King. Drawing on Raymond Arsenault’s work, B. J. Hollars also writes about a “cultural shift” signified within the civil rights movement itself by the Freedom Riders’ actions. In the eyes of both Arsenault and Hollars, the Freedom Riders’ activities have introduced a degree of intensity and an acceleration in changes that was, until 1961, unmatched in the civil rights protests; they also insist on the fact that the Riders’ story reflects how the civil rights movement, as of 1960 or 1961, was clearly under the leadership of the youth.

The reader interested in personal testimonies from the Freedom Riders could turn to B. J. Hollars’ book, whose content is mostly based on personal interviews with the Freedom Riders. You could also refer to Carol Ruth Silver’s published diary, a memoir of her time as an inmate in the Parchman prison farm – Silver is the only Freedom Rider among more than three hundred others who were also imprisoned at the same facility to have written a comprehensive testimony of her experiences.

RESEARCH & WRITING

Louise-Helene Filion, Ph.D.

PHOTO RESEARCH

Rebecca Phoenix

Bibliography:

Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Riders. 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, New York, Oxford University Press, Inc., 2006, 690 p.

Barnes, Catherine A. Journey from Jim Crow. The Desegregation of Southern Transit, New York, Columbia University Press, 1983, 313 p.

Digital SNCC Gateway, “April 1947. Congress of Racial Equality organizes Journey of Reconciliation.”

https://snccdigital.org/events/cores-journey-of-reconciliation/ . Accessed 4 February 2022.

Hollars, B.J. The Road South. Personal Stories of the Freedom Riders, Tuscaloosa, The University of Alabama Press, 2018, 171 p.

Silver, Carol Ruth. Freedom Rider Diary. Smuggled Notes from Parchman Prison, Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 2014, 188 p.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research & Education Institute at Stanford University, “Freedom Rides.” https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/freedom-rides . Accessed 4 February 2022.

The Obama Foundation, “Voices of the Freedom Riders.” https://www.obama.org/honoring-freedom-riders/ . Accessed 4 February 2022.

- Catherine A. Barnes, Journey from Jim Crow. The Desegregation of Southern Transit, New York, Columbia University Press, 1983, p. 157.

- B. J. Hollars, The Road South. Personal Stories of the Freedom Riders, Tuscaloosa, The University of Alabama Press, 2018, p. 2.

- Catherine A. Barnes, Journey from Jim Crow. The Desegregation of Southern Transit, op. cit., p. 158.

- Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders. 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, New York, Oxford University Press, Inc., 2006, p. xi.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. xii and p. 2; and B. J. Hollars, The Road South. Personal Stories of the Freedom Riders, op. cit., p. 5.

- Catherine A. Barnes, Journey from Jim Crow. The Desegregation of Southern Transit, op. cit., p. 169.

- Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders. 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, op. cit., p. 439.

- Ibid., p. 439-440.

- Ibid. Carol Ruth Silver, Freedom Rider Diary. Smuggled Notes from Parchman Prison, Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 2014, 188 p.

- Australia edition

- International edition

- Europe edition

Racial segregation on US inter-state transport to end – archive, 1955

26 November 1955: The new rules put an end to the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine which had been in place for many years

Washington, November 25 The Inter-state Commerce Commission ruled to-day that racial segregation on inter-state trains and passenger buses must end by January 10, 1956. It also ruled that segregation of inter-state travellers in public waiting-rooms is unlawful.

These two rulings put an end to the “separate but equal” doctrine which had guided the commission’s rulings for many years. Two months after the commission was established in 1887 it had its first case on racial discrimination. It then held that segregation would be most likely to produce peace and order and to promote “dignity of citizenship” in the United States.

In to-day’s opinion the commission said that “it is hardly open to question that much progress in improved race relations has been made since then.” When the Supreme Court outlawed compulsory segregation in state schools it ruled that segregation in itself excluded the concept of equality and imposed an inferior status on these American citizens. It is this new concept which has now prevailed with the commission.

In to-day’s ruling the commission said:

“The disadvantage to a traveller, who is assigned accommodations or facilities so designated as to imply his inherent inferiority solely because of his race, must be regarded under present conditions as unreasonable. Also, he is entitled to be free of annoyances, some petty and some substantial, which almost inevitably accompany segregation even though the rail carriers, as most of the defendants have done here, sincerely try to provide both races with equally convenient and comfortable cars and waiting rooms.”

Commissioner Johnson, of South Carolina, in a dissenting opinion, said “It is my opinion that the commission should not undertake to anticipate the Supreme Court and itself become a pioneer in the sociological field.”

Precautions in Georgia It should be understood that to-day’s rulings apply only to travel between states. The rulings have no effect on travel within a Southern state. Mr Eugene Cook, Attorney-General for Georgia, said he would try to use all legal procedures to maintain racial segregation “on travel within Georgia itself.” He conceded the difficulties because it is often hard to separate inter-state travellers from those travelling within the state alone. However, he had asked his legal staff to study this problem while giving first priority to Georgia’s continued resistance to a unified public school system in the state.

The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People also tried to have the commission end segregation in the lunch room at the Union Station in Richmond, Virginia. The commission said that this room was operated under lease by the Union News Company, which is not itself engaged in transportation, and therefore does not come within the commission’s jurisdiction. The commission also dismissed a complaint against the Texas and Pacific Railway Company because the evidence failed to show that the case involved inter-state travel.

Ten years ago, the commission authorised Southern Railways to serve Negro passengers in the dining-car behind a curtain in seats reserved exclusively for them. This method of segregation aroused intense public criticism and it was finally outlawed by the Supreme Court in 1950. To-day’s rulings are a notable advance of those started by the Court in 1950.

- From the Guardian archive

- Civil rights movement

- US politics

Most viewed

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 15, 2023 | Original: November 12, 2009

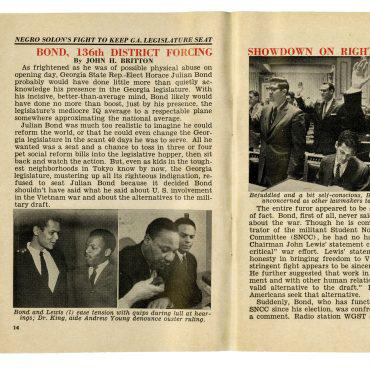

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was founded in 1960 in the wake of student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters across the South and became the major channel of student participation in the civil rights movement . Members of SNCC included prominent future leaders such as former Washington, D.C. Mayor Marion Barry, Congressman John Lewis and NAACP chairman Julian Bond.

SNCC Emerges From the Sit-In Movement

In February 1960, four Black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, stayed in their seats at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter after the staff refused to serve them. Some 300 students soon joined their protest, which received widespread media coverage, sparking a movement of similar sit-ins by thousands of students at segregated establishments across the South.

Civil rights leaders recognized such young activists as a powerful new force in their efforts to combat racial discrimination and win equal rights for Black Americans. As the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. acknowledged in a speech at a North Carolina church in mid-February 1960: “What is new in your fight is the fact that it was initiated, fed, and sustained by students.”