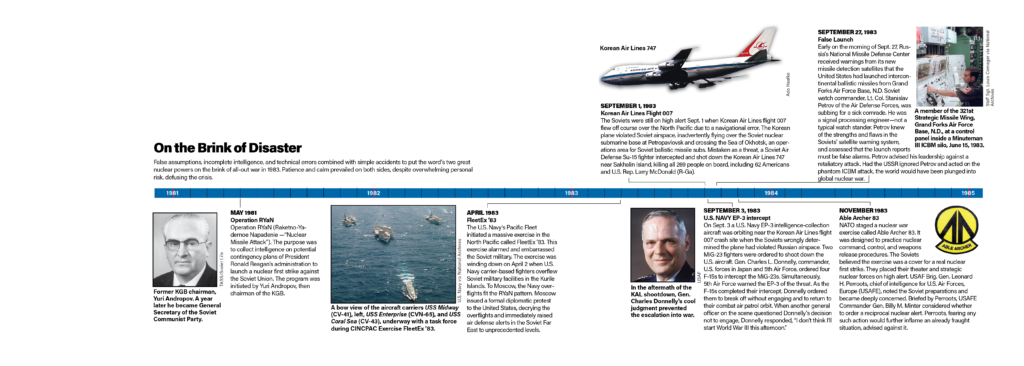

The Near Nuclear War of 1983

How the Air Force helped avert a nuclear catastrophe and save the world .

Related Content

Thomas c. reed, secretary of the air force under ford and carter, dies at 89, photos: 12 b-2s conduct massive fly-off, elephant walk, sticker shock drags out usaf’s e-7 negotiations with boeing, b-52 bombers make rare landing at civilian airport, why a civilian defense employee died after a c-17 test flight last year, q&a: outgoing afcent boss grynkewich on the future of the middle east, upset with divestment, congress impatient for fighter recap strategy, air force unveils first picks for new ‘quick start’ funding stream, f-35 program says gao report title misleading; sustainment costs coming down.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Robert Beckhusen

New Documents Reveal How a 1980s Nuclear War Scare Became a Full-Blown Crisis

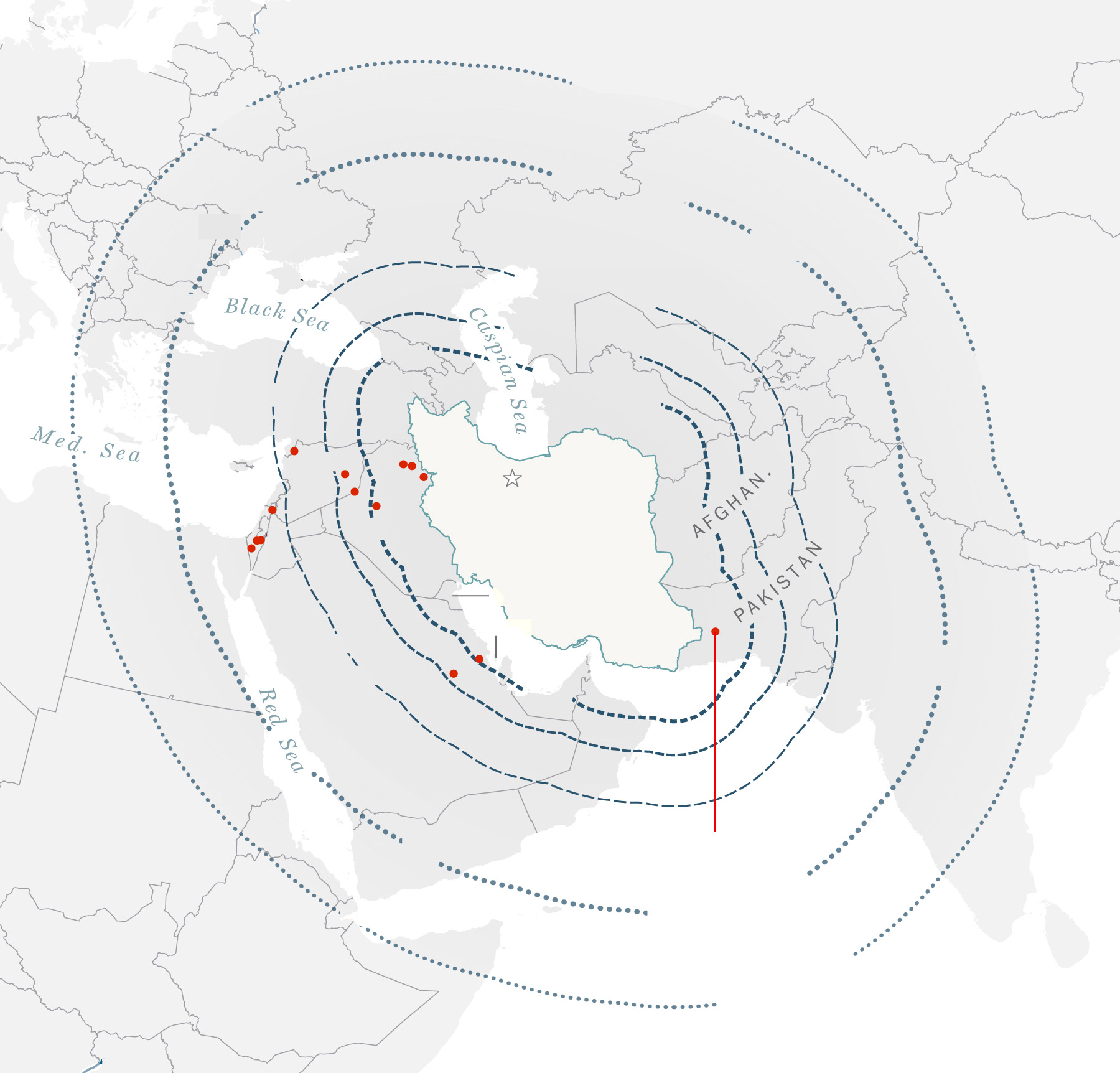

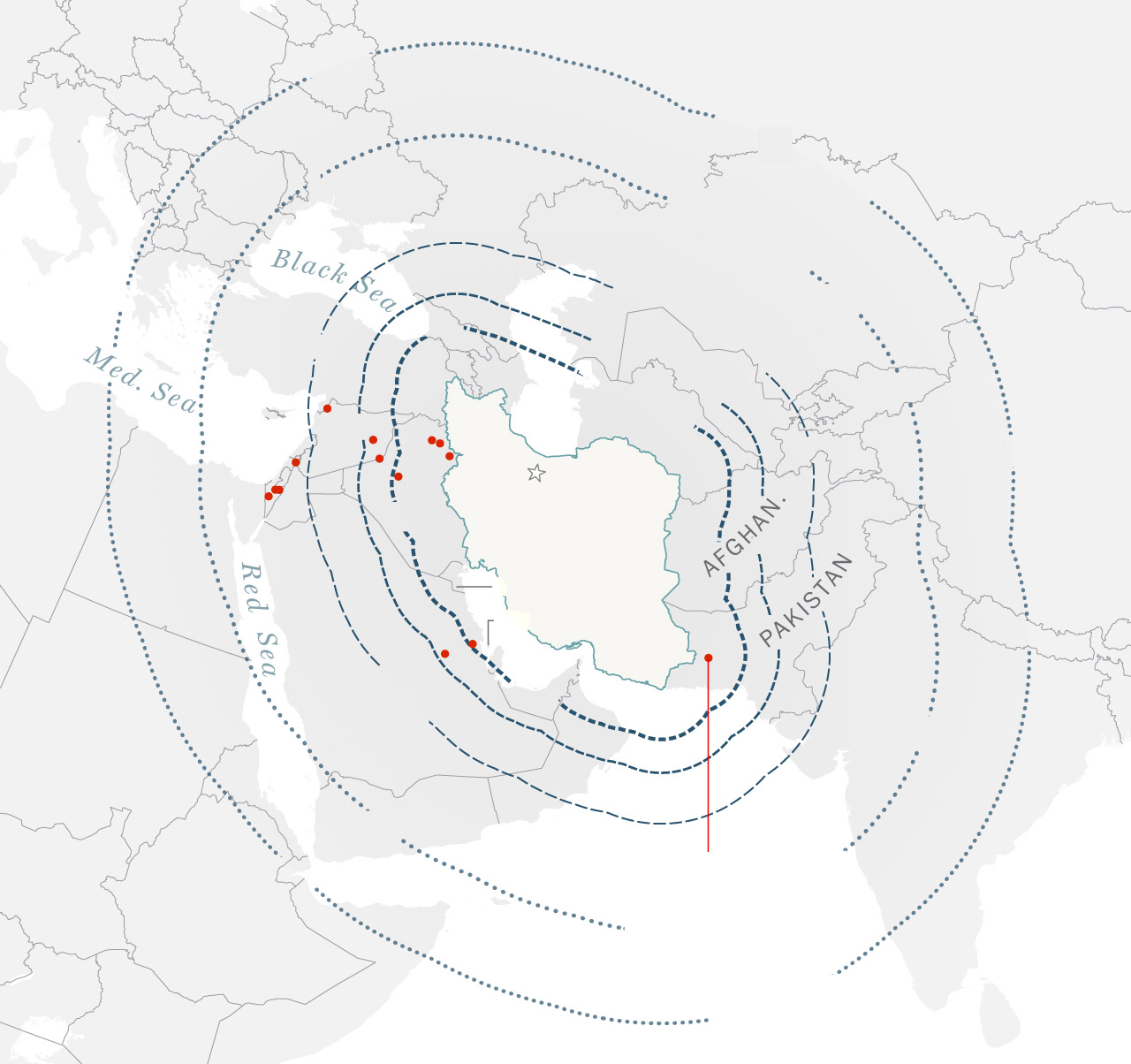

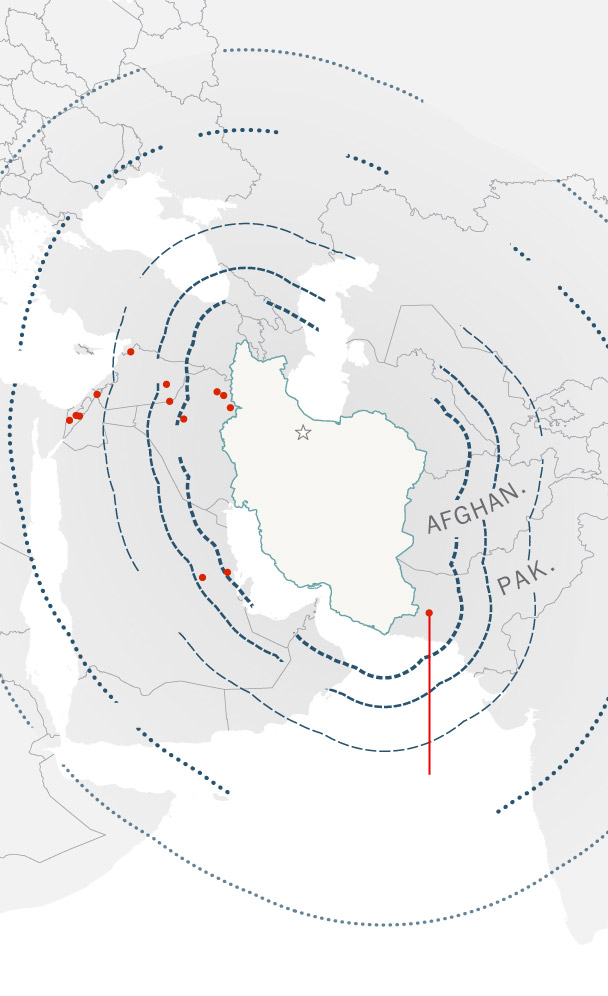

During 10 days in November 1983, the United States and the Soviet Union nearly started a nuclear war. Newly declassified documents from the CIA, NSA, KGB, and senior officials in both countries reveal just how close we came to mutually assured destruction -- over a military exercise.

That exercise, Able Archer 83, simulated the transition by NATO from a conventional war to a nuclear war, culminating in the simulated release of warheads against the Soviet Union. NATO changed its readiness condition during Able Archer to DEFCON 1 , the highest level. The Soviets interpreted the simulation as a ruse to conceal a first strike and readied their nukes. At this period in history, and especially during the exercise, a single false alarm or miscalculation could have brought Armageddon.

According to a diplomatic memo obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by National Security Archives researcher Nate Jones, Soviet General Secretary Yuri Adroprov warned U.S. ambassador Averell Harriman six months before the crisis that both countries "may be moving toward a red line" in which a miscalculation could spark a nuclear war. Harriman later wrote that he believed Andropov was concerned "over the state of U.S.-Soviet relations and his desire to see them at least 'normalized,' if not improved."

The early 1980s was a "crisis period, a pre-wartime period," said Gen. Varfolomei Korobushin, the former deputy chief of staff of the Soviet nuclear Strategic Rocket Forces, according to an interview conducted by the Pentagon in the early 1990s and obtained by Jones. The Kremlin's Central Committee slept in shifts. There were fears the deployment of Pershing II ballistic missiles to Europe (also in November 1983) could tip the balance. If a conventional war erupted, Soviet planners worried their troops would come close to capturing the nuclear-tipped missiles, prompting the United States to fire them.

The Soviet Union, according to an unclassified article written for the CIA's classified Studies in Intelligence journal and provided to Jones, notes that Soviet fears of a preemptive American nuclear attack "while exaggerated, were scarcely insane." This stemmed from the Soviet experience during World War II, when the Third Reich launched Operation Barbarossa, the largest invasion in human history. Soviet officials worried history might be repeated by NATO.

Oleg Gordievsky , a CIA and MI6 source during the Cold War , was previously known to have warned the West about these fears, but the CIA article identifies a second source of this information: a Czech intelligence officer with ties to the KGB who "noted that his counterparts were obsessed with the historical parallel between 1941 and 1983. He believed this feeling was almost visceral, not intellectual, and deeply affected Soviet thinking."

President Reagan wasn't sure, and in March, 1984, asked Arthur Hartman, his ambassador to the Soviet Union, "Do you think Soviet leaders really fear us, or is all the huffing and puffing just part of their propaganda?" We don't know what Hartman said in response, but John McMahon, the CIA director at the time, believed the Soviets were simply "rattling their pots and pans" to stop further Pershing II deployments.

Emily Mullin

Joel Khalili

C. Brandon Ogbunu

It's unclear how much of the fear was just pots and pans. Jones writes that although "real-time analysts, retroactive re-inspectors, and the historical community may be at odds as to how dangerous the War Scare was, all agree that the dearth of available evidence has made conclusions harder to deduce." Jones did not get all the information he asked for. (The complete list of unclassified documents are collected at the Archives' website , with two more sets of documents to follow.) The NSA told him it had 81 more documents, but did not release them. However, it did "review, approve for release, stamp, and send a printout of a Wikipedia article ," he noted.

Still, we do have more evidence of serious Soviet preparations. Documents obtained by Jones detail a massive KGB intelligence-gathering mission called Operation RYaN . (The name is a Russian acronym for "nuclear missile attack.") According to the CIA article, RYaN was "for real" and accelerated in the early 1980s during the scare. The goal was to find out if and when the United States and NATO would attack. According to KGB instructions sent to agents in London, Soviet spies were to monitor bomb shelters, blood banks, military bases and key financial and religious leaders for signs of war preparations. "Many of the assigned observations would have been very poor indicators of a nuclear attack," Jones warns.

But in another sense, the scrambling for any scrap of intelligence -- whether good or bad -- reflected a feverish belief among some quarters that war was just around the corner. "[T]he Reagan administration marked the height of the Cold War," notes one declassified history published by the National Security Agency. "The president referred to the Soviet Union as the Evil Empire, and was determined to spend it into the ground. The Politburo reciprocated, and the rhetoric on both sides, especially during the first Reagan administration, drove the hysteria. Some called it the Second Cold War. The period 1982-1984 marked the most dangerous Soviet-American confrontation since the Cuban Missile Crisis."

Worse, there were "a lot of crazy people" in the Kremlin and Soviet military command, according to Vitalii Tsygichko, an analyst for the Soviet General Staff who was interviewed by the Pentagon. "I know many military people who look like normal people, but it was difficult to explain to them that waging nuclear war was not feasible. We had a lot of arguments in this respect. Unfortunately, as far as I know, there are a lot of stupid people both in NATO and our country."

Considering the consequences of a war, and how close it came, those comments certainly ring true.

Matt Burgess

Andrew Couts

Andy Greenberg

Eric Geller

David Nield

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

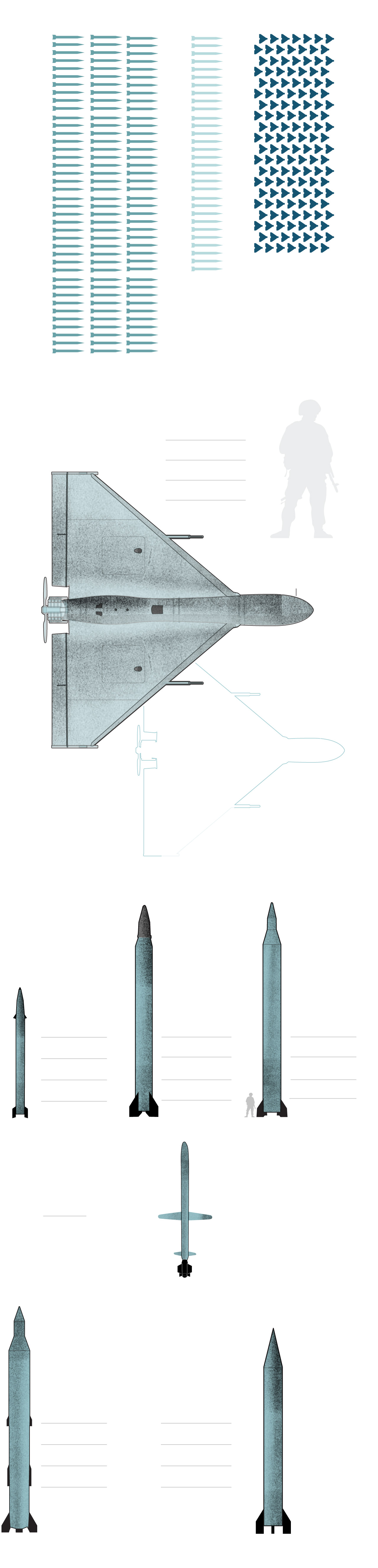

Cruise missiles in Europe (1979 to 1980)

In December 1979 Nato announced that, in response to the Soviet's stockpiling of their nuclear weapons, Cruise missiles would be sited in Europe. Since Cruise missiles were designed to be 'first-strike' weapons, this was a clear sign that the US nuclear doctrine of deterrence had shifted to one aiming to fight, and win, a nuclear war. In response, the Soviet Union withdrew its offer to negotiate.

Government announce that RAF base at Greenham Common will house nuclear missiles

In July 1980 Secretary of State for Defence Francis Pym told the House of Commons that a total of 160 Cruise missiles would be located at RAF Greenham Common, Berkshire, as well as the disused RAF Molesworth in Cambridgeshire. The UK would contribute 220 personnel to help guard the bases and the cost to the country would be £16m. There was no public debate.

Protest at Greenham (1981 to 1983)

- Greenham Common

- Your Greenham

Most viewed

The 1983 Military Drill That Nearly Sparked Nuclear War With the Soviets

Fearful that the Able Archer 83 exercise was a cover for a NATO nuclear strike, the U.S.S.R. readied its own weapons for launch

Francine Uenuma

History Correspondent

:focal(2658x1772:2659x1773)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/35/45/35454cad-58f2-47d8-b454-1af06a783731/gettyimages-542405164.jpg)

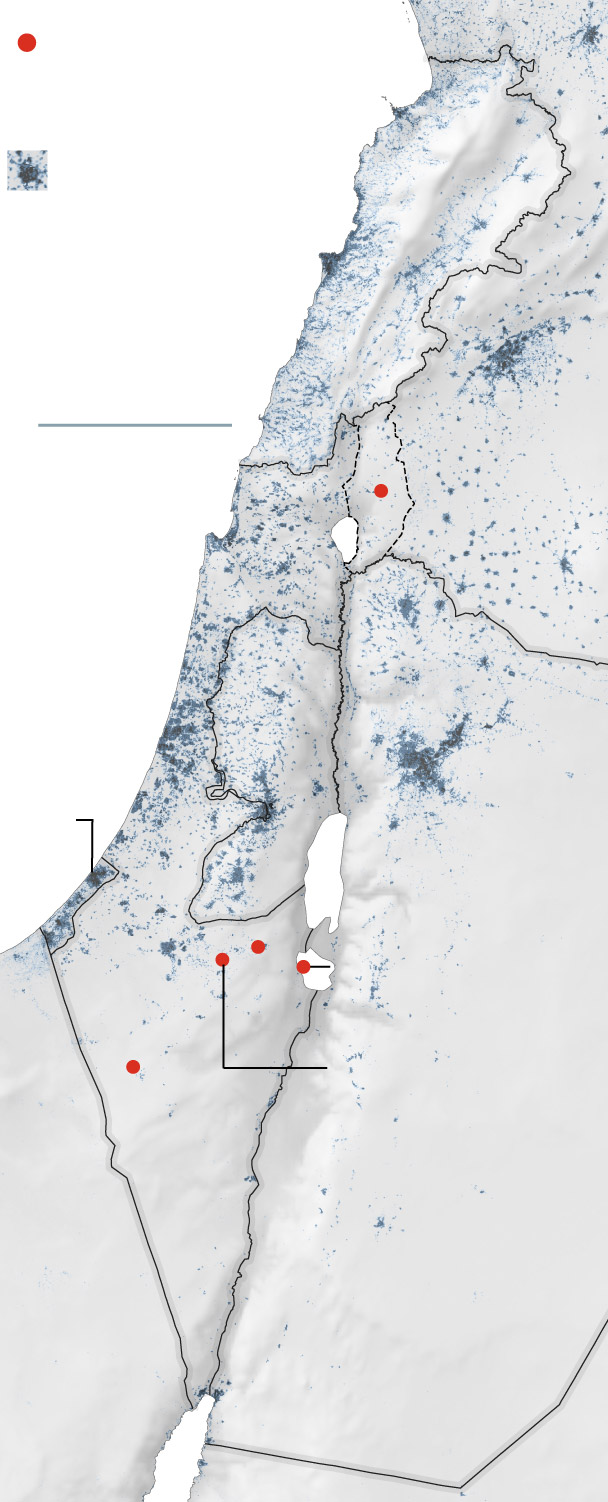

In November 1983, during a particularly tense period in the Cold War, Soviet observers spotted planes carrying what appeared to be warheads taxiing out of their NATO hangars. Shortly after, command centers for the NATO military alliance exchanged a flurry of communication, and, after receiving reports that their Soviet adversaries had used chemical weapons, the United States decided to intensify readiness to DEFCON 1—the highest of the nuclear threat categories , surpassing the DEFCON 2 alert declared at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis two decades prior. Concerned about a preemptive strike, Soviet forces prepared their nuclear weapons for launch.

There was just one problem. None of the NATO escalation was real—at least, not in the minds of the Western forces participating in the Able Archer 83 war game.

A variation of an annual military training exercise, the scenario started with a change in Soviet leadership, heightened proxy rivalries and the Soviets’ invasion of several European countries. Lasting five days, it culminated in NATO resorting to the use of nuclear weapons. Soviet intelligence watched the event with special interest, suspicious that the U.S. might carry out a nuclear strike under the guise of a drill. The realism of Able Archer was ironically effective: It was designed to simulate the start of a nuclear war, and many argue that it almost did.

“In response to this exercise, the Soviets readied their forces, including their nuclear forces, in a way that scared NATO decision makers eventually all the way up to President [Ronald] Reagan,” says Nate Jones , author of Able Archer 83: The Secret History of the NATO Exercise That Almost Triggered Nuclear War and a senior fellow at the National Security Archive .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/9a/f59a7b07-783e-482b-886d-e1add9b43633/gettyimages-1003574910.jpg)

Perhaps most concerning is that the danger was largely unknown and overlooked, both during the exercise and throughout that precarious year , when changes in leadership and an acceleration in the nuclear arms race ratcheted up tensions between the two superpowers. A since-declassified 1990 report by the President’s Foreign Intelligence Review Board (PFIAB) concluded, “In 1983 we may have inadvertently placed our relations with the Soviet Union on a hair trigger.”

Almost 40 years later, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has evoked comparisons with the Cold War, particularly when it comes to Russian President Vladimir Putin ’s vaguely worded threats. At the onset of the war, Putin warned of “consequences you have never seen”—a declaration interpreted in some quarters as a nod to his country’s nuclear capabilities. More recently, U.S. President Joe Biden’s announcement of new weapons for Ukraine elicited an admonition from Moscow about “unpredictable consequences.” Biden has declined to send American troops and cautioned that “direct confrontation between NATO and Russia is World War III.”

“The Russians have made some allusions not rising to the level of explicit threats, but it’s very, very strongly implied,” says Edward Geist , a policy researcher at the RAND Corporation , a nonprofit global policy think tank. Though he doesn’t see a commensurate change in Russia’s actions or positioning of nuclear assets, Geist interprets the message being sent to NATO as “you don’t want to actually get directly involved in this because that could escalate to nuclear war. … It’s not worth the risk, so you should stay out and let us do what we want in Ukraine.”

By the fall of 1983, the U.S. and the Soviet Union had reached a point of mutually assured misunderstanding. Relations between the two nations were at a particularly low ebb in the decades-long Cold War, which had emerged out of the ashes of World War II. The elimination of a common enemy—Nazi Germany—allowed the victors to shift their focus to each other as rivals. Following America’s use of an atomic weapon against Japan in 1945 and the Soviet Union’s own nuclear test in 1949, the arms race began in full effect.

NATO, a security alliance established between the U.S. and Western European nations in 1949, was mirrored by the Warsaw Pact , a defense treaty signed by the Soviet Union and members of its Eastern Bloc. Two years after the Warsaw Pact’s formation in 1955, the Soviets launched the world’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik I , placing space on the playing field even as the rivalry continued to take shape on Earth through proxy wars in Asia. In the 1970s, a mood of détente prevailed as President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev reached a series of agreements aimed at arms control.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f9/90/f990807b-3dbd-4f15-ac78-99bd7c711d15/gettyimages-515564276.jpg)

Early in the next decade, with new leadership on both sides, détente had evaporated. After taking office in 1981, Reagan matched his campaign rhetoric by initiating a doubling of the defense budget . Soviet leader Yuri Andropov, who assumed power the following year , came to the job after heading the KGB, where he initiated Operation RYaN , whose name is an acronym describing a sudden nuclear attack. “The main objective of our intelligence service is not to miss the military preparations of the enemy … for a nuclear strike,” Andropov said in 1981 .

Operation RYaN lent itself to confirmation bias, with many routine activities—such as official visits or blood drives—feeding fears of war. And when it came to looking for signs of imminent attack, Able Archer fit the bill.

On the American side, defense and intelligence officials “shared the long-held view that ‘the U.S. doesn’t do Pearl Harbors,’” writes historian Taylor Downing in 1983: Reagan, Andropov and a World on the Brink . The Americans therefore assumed the Soviets knew they had no intention of launching a preemptive nuclear attack. Early intelligence estimates after Able Archer dismissed apparent Soviet fears as a ploy to slow American defense buildup. As the PFIAB report noted, analysts “identified signs of emotional and paranoid Soviet behavior” yet saw “motives for trying to cleverly manipulate Western perceptions.”

It was a vicious circle. The Soviets refused to believe the Americans were bluffing; the Americans, meanwhile, suspected the Soviets were bluffing about not thinking the Americans were bluffing.

A series of inflammatory events that year paved the way for the fraught moments of Able Archer. In a March speech to the National Association of Evangelicals, Reagan characterized the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” and decried those “who would place the United States in a position of military and moral inferiority.”

Later that month, the president announced plans for the Strategic Defense Initiative (popularly dubbed “Star Wars”), which aimed to intercept incoming nuclear missiles from space. Reagan viewed it purely as a defensive measure, but the Soviet Union saw a shield that would enable the U.S. to take offensive action by reducing its fear of retaliation. Such protection would undermine the notion of mutually assured destruction , which was seen as a grim deterrent for starting a nuclear war.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3d/87/3d873a01-48b5-4df7-beee-eda5f7cffa27/kal_007_protests.jpeg)

American military planes and ships pressed at Soviet borders in so-called PSYOPS, or psychological operations —shows of force that further aggravated the Soviets. In the spring of 1983, the looming presence of these American warcraft prompted Andropov to adopt a policy of “ shoot to kill ” at any similar incursion.

On the night of September 1, the civilian airliner Korean Airlines 007 went off course on its flight from Anchorage to Seoul. The Soviets, mistaking the plane for a military aircraft, shot it down, killing all 269 people on board. Reagan called it a “ massacre .”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/13/6f/136f31ff-cdb5-4378-b895-900f7a506cf6/pershing_ii.jpeg)

Perhaps most alarming to the Soviets was NATO’s deployment of new intermediate-range ballistic and cruise missiles that could strike the U.S.S.R.—and Moscow itself—faster than previously possible. Though this operation took place in response to the Soviets’ development of similarly potent missiles in the late 1970s, Soviet leaders still saw the move as menacing. Just weeks before Able Archer, Soviet Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov characterized the NATO missiles “as means for a first strike, the ‘decapitation strike,’” in a meeting with fellow Warsaw Pact officials, according to documents held by the National Security Archive. The threat posed by the missiles increased the argument for a launch on warning strategy, which made speed—and therefore a decrease in decision-making time—the linchpin of defense.

In June, during a private meeting with a former American emissary to Moscow, Andropov expressed fears of a conflagration far worse than the Second World War, in which the two nations had been allies. “This war may perhaps not occur through evil intent,” he said , “but could happen through miscalculation.”

Able Archer 83 was part of a constellation of recurring NATO exercises. But some elements—including the dummy warheads, the DEFCON status changes and communications patterns (including periods of speculation-inducing radio silence)—were unique to that year. Managed out of NATO’s headquarters in Brussels and involving components across Western Europe, the training simulated coordination across the alliance’s commands in response to aggression by the Warsaw Pact.

As the Able Archer scenario intensified, the head of the Soviet air forces ordered a state of readiness that “included preparations for immediate use of nuclear weapons,” according to later-declassified sources referenced in a memorandum by Lieutenant General Leonard Perroots , then the Air Force’s assistant chief of staff for intelligence in Europe. During the exercise, analysts concluded that at least one squadron “was loading a munitions configuration that they had never actually loaded before.” Perroots’ concerns were echoed by the PFIAB, which called the reaction of Soviet intelligence, including 36 surveillance flights, “unprecedented.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/88/db/88dbd1a1-9c3e-4b13-ac0a-a854802b3e6e/reagan_and_gordievsky.jpeg)

At the time, Perroots chose to continue monitoring development and not escalate in kind. (His prudent inaction has drawn comparisons to Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, who correctly interpreted a false alarm of nuclear attack that September.) In his memorandum, Perroots outlined a “potentially disastrous situation,” one that he found even more alarming after Oleg Gordievsky , a high-level KGB officer who served as a double agent for the British, revealed that the Soviet security agency believed Able Archer would serve as an ideal “cover” for an attack. After the exercise, with the benefit of hindsight, the PFIAB report called Perroots’ patience a “fortuitous, if ill-informed, decision.”

“We now know how nervous the [Soviet] leadership became, ... [putting] the entire [state] arsenal with its 11,000 warheads on to maximum combat alert,” writes Downing in his book. He describes a seriously ill Andropov conferring with military leaders at a clinic outside of Moscow as the exercise proceeded apace, capturing the essence of the problem that was at the crux of Able Archer and the “war scare” as a whole: “It was impossible for satellites to pick up any insight into the state of paranoia in the Soviet leadership.”

Though these men never publicly mentioned Able Archer by name, glimpses into their mindsets at the time are available. Days after Able Archer concluded, defense minister Ustinov wrote in the state-run Pravda newspaper that NATO’s exercises “are becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish from a real deployment of armed forces for aggression.”

Blind spots were plentiful on both sides. Robert Gates , then the CIA’s deputy director for intelligence, told Downing that “we may have been at the brink of nuclear war and not even known it.” In retrospect, the “miscalculation” that Andropov had feared five months earlier seemed plausible.

Scholars still debate exactly how dangerous this juncture was. Simon Miles of Duke University has argued that the retrospective analysis of Able Archer is overblown, as evidenced by Soviet actions that fell short of their nuclear capabilities. Contemporary extrapolations based on what the Soviets did or did not do will always be impossible to fully prove or disprove.

The Soviets refused to believe the Americans were bluffing; the Americans, meanwhile, suspected the Soviets were bluffing about not thinking the Americans were bluffing.

Jones, who is also the Freedom of Information Act director for the Washington Post , notes that some information about the exercise remains inaccessible to the public; even portions of the 1990 PFIAB report are redacted. “I would say to the skeptics that the more that’s declassified, the more scary it looks,” he adds.

The precarious decline of U.S.-Soviet relations throughout those months left an impression on Reagan. Presented with a summary of recent Soviet actions that pointed to broader war preparations—including the bolstering of domestic civil defenses, the pattern of troop movements within the country and shifts from commercial to military use—the president called them “really scary.”

Reagan’s November 18, 1983, diary entry reflects a realization that these fears were genuine: “I feel the Soviets are so defense minded, so paranoid about being attacked that without in any way being soft on them we ought to tell then no one here has any intention of doing anything like that. What the h—l have they got that anyone would want.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/63/ed/63edbfdc-5f95-40c1-9ba0-23558768b61a/2560px-president_ronald_reagan_making_his_berlin_wall_speech.jpeg)

The ensuing years brought a reduction in tensions that led to the end of the Cold War. The shift in Reagan’s approach was complemented by the ascension of Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. Despite leading on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum, the two men found avenues for cooperation in the later 1980s.

The Cold War is now three decades in the rearview mirror, and the invasion of Ukraine is a far cry from a fictional exercise. But while history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself , it does mutate—and once again, nuclear-tinged rhetoric is making headlines .

Geist considers the nuclear threat low risk at present but acknowledges that the mere specter of it still carries great influence. “It’s framing what is considered possible for basically all ... foreign governments, including our own,” he says. “The idea of direct intervention would be much more seriously considered against a non-nuclear power.”

Common to this or any other chapter of the post-World War II nuclear world is the fact that no nuclear threat, whether vague or explicit, comes without a degree of risk. As Jones point out, “The danger of brinksmanship ”—a foreign policy practice that pushes parties to the edge of confrontation—“is it’s easier than we think for one side to fall into the brink.”

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Center for International Maritime Security

The Politics of Naval Innovation: Cruise Missiles and the Tomahawk

The following republication is adapted from a chapter from The Politics of Naval Innovation , a paper sponsored by the Office of Net Assessment and conducted by the Strategic Research Department of the U.S. Naval War College’s Center for Naval Warfare Studies. Read it in its original form here.

By CDR Gregory A. Engel

This chapter explores the origins of the modern cruise missile and the ultimate development of the Tomahawk cruise missile, particularly the conventional variant. In keeping with the theme of the study, it focuses on the politics of cruise missile development and the implications as they relate to a Revolution in Military Affairs. The full history of cruise missiles can be traced to the development of the V-1 “buzz bomb” used in the Second World War. Since this history is available in many publications, it will not be discussed here nor is it especially pertinent to modern cruise missile development. Worth noting, however, is that the enthusiasm of many early Harpoon and Tomahawk advocates can be linked to the Regulus and other unmanned aircraft programs of the 1950s and 1960s.

What this chapter will show is that although air- and sea-launched cruise missiles (ALCM/SLCM) began along different paths neither would have come to full production and operation had it not been for intervention from the highest civilian levels. Having support from the top, however, did not mean there were not currents, crosscurrents, and eddies below the surface (i.e., at the senior and middle military levels) stirring up the political waters. Studying the challenges faced by cruise missile advocates and how they were overcome can provide valuable lessons for those tasked with developing tomorrow’s technological innovations.

The development of the modern cruise missile spanned nearly fifteen years from conception to initial operational capability (IOC). To those introduced to the cruise missile on CNN during the Gulf crisis in 1991, however, the modern cruise missile seemed more like an overnight leap from science fiction to reality. But as this chapter will show, both cruise missile technology and doctrinal adaptations were slow to be accepted.

The political and bureaucratic roads to acceptance of the sea-launched cruise missile were never smooth. As Ronald Huisken noted, “The weapons acquisition process is a most complex amalgam of political, military, technological, economic, and bureaucratic considerations …. Rational behavior in this field is particularly hard to define and even harder to enforce.” 1 Since they first became feasible, the Navy demonstrated an interest in cruise missiles. But finding a champion for them among the Navy’s three primary warfighting “unions” (associated with carrier aviation, submarines and surface warfare) proved difficult. Despite the cancellation of the Regulus program in the 1960s, some surface warfighters aspired to develop an antiship cruise missile which could compete with evolving Soviet technologies. But carrier aviation was the centerpiece of naval war at sea, so initially little support could be garnered for a new variety of surface-to-surface missile. As the requirement for an antiship missile became more evident following the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) were given some surface-to-surface capability. 2

However, following the 1967 sinking of the Israeli destroyer Eilat by an Egyptian SSN-2 Styx missile, Admiral Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt, Jr., then a Rear Admiral and head of the Systems Analysis Division, was directed by Paul Nitze, the Secretary of the Navy, via Admiral Thomas Moorer, the Chief of Naval Operations, to initiate a study on cruise missiles that eventually led to the Harpoon.

When Nitze directed the Navy to undertake the study on surface-to-surface missiles, there were two prevailing military requirements. The first was that the US needed such a capability to counter the growing strategic potential of the Soviets. The second was to improve the US’s strategic balance. During this period, there was growing alarm over the rapidly expanding Soviet nuclear missile arsenal and the naval shipbuilding race which (to some) the Soviets appeared to be winning. Admiral Zumwalt was one of those concerned individuals and saw the cruise missile as a required capability. He brought this conviction with him when he became the Chief of Naval Operations in July 1970. 3

Naval doctrine at this time held that US surface vessels did not need long-range surface-to-surface capabilities as long as carrier aviation could provide them. 4 Many in Congress shared this view. Against this backdrop, Zumwalt and other likeminded advocates of cruise missiles began their efforts to gain acceptance of cruise missiles within the Navy and on the Hill.

Following over two years of study and tests, a November 1970 meeting of the Defense Select Acquisition Review Council (DSARC) approved the development of the AGM-84 Harpoon missile. By this time, the Harpoon had both sea- and air-launched variants. Within the Navy, the Harpoon had been bureaucratically opposed by the carrier community because it posed a threat to naval aviation missions. During the Vietnam War period, the carrier union was a major benefactor of naval defense funding and it did not want to support any weapons system which could hinder or compete with aircraft or carrier acquisition programs. In order to gain their support, the Harpoon was technologically limited in range. 5

The Harpoon project had been under the direction of Navy Captain Claude P. “Bud” Ekas with Commander Walter Locke serving as his guidance project officer. Both officers were later promoted to Rear Admiral. In 1971, the Navy began studying a third Harpoon variant, one which could be launched from submarine torpedo tubes. Concurrently, the Navy began a program to study the Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM). This advanced model was to have an extended range of over 300 miles and to be launched from vertical launch tubes. 6 This proposal was generally supported by the submarine community (the criticality of this support will be discussed later).

With the advent of the ACM, it was decided to create the advanced cruise missile project office with Locke as director. The Naval Ordnance Systems Command (NAVORD) wanted control of the ACM project and argued that it was the appropriate parent organization for submarine-launched missiles. Admiral Hyman Rickover and other OPNAV submarine admirals opposed this believing that Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) was more imaginative and efficient than NAVORD. The earlier assignment of the ship- and air-launched Harpoon to NAVAIR had effectively co-opted the technical leadership of naval aviation. As a result, the ACM program remained under NAVAIR where work proceeded rapidly…. 7

….The ACM program of 1971, which barely lasted two years, was significant in that it formed the political, fiscal, and technological connection between the Harpoon and the Tomahawk. Long-range cruise missile advocates within the Navy were having difficulty promoting the larger submarine-launched cruise missile because of the ACM’s need for a new submarine. In 1973, they admitted they had no urgent military requirement for a long-range tactical (anti-ship) variant of the SLCM, but they justified it as a bargain with small added cost to strategic cruise missile development. SLCM represented a technological advancement of untold potential that begged for a home. Congressional and OSD acceptance of the ACM paid the bulk of the development costs of a tactical (anti-ship) variant of the SLCM. 19 This all fit fortuitously into the timeframe when SALT I negotiators were searching for strategic options.

By mid-1972, there was little support for the tactical nuclear variant of the ACM and the critics within the Navy were powerful. Thus Ekas and Locke worked to link the ACM development team with OSD strategic advocates. Funding and advocacy remained available within OSD for strategic versions of the SLCM. “It was thus only sensible to arrange a marriage of convenience. With Zumwalt’s manipulation, Laird’s intervention thus set the Navy on a nearly irreversible course. By 6 November 1972 – the date of the consolidation order – surface fleet proponents of a new surface-to-surface missile had effectively won their battle, even if they did not realize it at the time.” 20 In December 1972, a new program office, PMA-263, was established and Captain Locke was transferred from the Harpoon Program Office to become the Program Manager. 21

Admiral Locke has noted that others in the Navy Department did not believe in the cruise missile. He received a telephone call in June 1972 from an OPNAV staff Captain directing him to “do the right thing” with the recently allocated project funding, i.e., get the money “assigned to things doing work that we can use afterward.” The implication was that the Pentagon had decided it was going to be a one-year program and then was going away. Cruise missiles were seen as a SALT I bargaining chip that made Congressional hawks feel good. 22 Not even all submariners were infatuated with the idea; but two submariners who did support it were Admiral Robert Long and Vice Admiral Joe Williams. Admiral Long, who was OP-02 (Deputy Chief of Naval Operations, Undersea Warfare), believed cruise missiles would do more than take up space for torpedoes – the most common complaint heard from submariners – and was its most influential advocate. 23 He was supported by Vice Admiral Williams, who was noted by Locke as also being important to the cruise missile program in the early 1970s…. 24

….Initial technical studies indicated that desired cruise missile ranges could not be obtained from a weapon designed to fit in a 21-inch torpedo tube; thus, the missile necessitated development of a new submarine fitted with 40-inch vertical launch tubes. Zumwalt, who understood this relationship, directed his Systems Analyses staff, OP-96, to argue against the submarine and criticize the cruise missile. 27 A curious position to be in as cruise missile advocates. 28 ADM Zumwalt was not prepared to concede the 60,000 SHP submarine to ADM Rickover for a variety of reasons, but primarily because it would decrement funding for other Project 60 items. Submariners believed that getting approval for installing the newly envisioned encapsulated Harpoon would eventually lead to a newer, increased capability torpedo. Without ADM Zumwalt’s knowledge, Joe Williams and Bud Ekas received approval from the Vice CNO, Admiral Cousins, to discretely prototype and test the encapsulated Harpoon. When advised of the results, ADM Zumwalt was chagrined that there was a possible submarine conspiracy underfoot but was eventually persuaded that the funding for further testing would be minimal (mainly for the canisters, tail sections, and the test missiles). There was also the possibility of SSNs carrying later versions of the Harpoon with greatly extended ranges which would allow strikes on the Soviet Navy when weather might preclude carrier aviation strikes in the northern latitudes. 29

Although ADM Zumwalt had relented, he remained wary of the submarine community’s desire for a new, larger submarine. As program manager for SLCM, Admiral Locke found himself allied with the submariners in order to garner funding support for his missile. Zumwalt threatened to end procurement of the 688-class SSN if Rickover continued to pursue the 60,000 SHP submarine. 30 When wind tunnel tests, which had been directed by Locke, indicated that the required range could be obtained from a cruise missile which could fit in the 21-inch torpedo tube, Rickover and other submariners agreed to halt their quest for a larger attack submarine in exchange for continued procurement of the 688-class and continued development of the cruise missile soon to be known as the Tomahawk. 31 Thus, the ACM project was quietly dropped in 1972, but the research on anti-ship cruise missiles continued as part of the SLCM program at Zumwalt’s personal insistence. 32 Following a January 1972 memo from the Secretary of Defense to the DDR&E which started a Strategic Cruise Missile program using FY 72 supplemental funds that were never appropriated, the CNO ordered that priority be given to the encapsulated Harpoon. 33

A fifth option eventually evolved and, as a result to Locke’s persistent effort with the OSD and OPNAV staffs, was accepted. That option was to proceed with the development of a cruise missile with both strategic and tactical nuclear applications that would be compatible with all existing potential launch platforms. What this fifth option really did was detach the missile’s technical challenges from a specific launch platform so that missile development could progress independently of the submarine issue. 34

In 1973, Defense Secretary Laird was replaced by Eliot Richardson. Although Richardson stated he supported Laird’s views on SLCM, his endorsement was neither as enthusiastic nor emphatic. He merely indicated that the United States should give some attention to this particular area of technology, for both strategic and tactical nuclear roles. Support from OSD did not wane, however, and was kicked into high gear by William P. Clements, the Deputy Secretary of Defense. President Nixon had handpicked Clements to assemble a team of acquisition experts from civilian industries to fill the OSD Under Secretaries positions. 35 Clements coordinated his efforts with Dr. Foster, who was still Director Defense Engineering and Research. All major defense projects were evaluated and those with the most promise were maintained or strengthened; those lacking promise were decreased or cancelled. He was also looking for programs that would give the US leverage, and when he learned about cruise missiles, he became a super advocate. 36 The cruise missile represented the cutting edge of new technology and held promise of a high payoff for low relative cost. It’s fair to say that the US “wouldn’t have had a cruise missile without Bill Clements grasping, conceptually, the idea and pushing the hell out it.'” 37

… Despite these technological breakthroughs, by 1974, missions for the cruise missile were still vague. Congress wanted to know why the Navy would be putting a 1,400 NM missile on submarines when, for years, they had been working to increase the distance from which they could launch attacks against the Soviet Union. They also wanted to know whether it was to be a strategic or tactical nuclear missile. The Air Force was still wary of a strategic SLCM because they didn’t want further Navy encroachment on their strategic missions. 45 Congress had additional misgivings about what effect the cruise missile would have on strategic stability since the strategic and tactical variants were virtually indistinguishable. No one denied that the cruise missile exhibited great promise, but it lacked a specified mission…

… This indistinct mission for the SLCM proved politically useful within the Navy (even though some in Congress believed it was strategic nonsense). Conceptual flexibility offered naval innovators the means of overcoming significant obstacles in their quest for a long-range surface-to-surface missile. It also offered Defense Department officials the opportunity to urge the Air Force to work on the ALCM. And because it was ambiguous, the new SLCM mission did not raise undue suspicion in the carrier community. As long as a strategic cruise missile appeared to be the goal, the tactical anti-ship version could be treated as a fortuitous spinoff. So, although the Navy drafted a requirement for an anti-ship version of the cruise missile in November 1974, it purposely paced its progress behind the strategic version. 48

This strategic rationale may have pacified Congress, but not Zumwalt. As early as 1974, Navy studies had specified the SSN as the launch platform for the SLCM even though that mission would require diverting them from their primary role, anti-submarine warfare (ASW). Zumwalt wanted cruise missiles on surface platforms as anti-ship weapons. Before he left office as CNO in 1974, he designated all cruisers as platforms for the SLCM, particularly the newly proposed nuclear-powered strike cruiser. This particular proposal was not well-received because some thought it would violate the requirement of minimizing the vulnerability of these platforms. Zumwalt received support from Clements who wouldn’t approve another new shipbuilding program unless Tomahawk cruise missiles were included. As a result, Zumwalt got what he wanted from the beginning – a capable anti-ship missile for the surface navy… 49

… Pursuit of a conventional land-attack variant was a watershed for the Tomahawk. By placing a land-attack missile on a variety of surface combatants, the Navy’s firepower was dramatically increased as was the Soviet’s targeting problem. But the real doctrinal breakthrough was that surface combatants could now mount land-attack operations independently of the Carrier Battle Group in situations where only a limited air threat existed. The Tomahawk Anti-ship Missile (TASM) was the only version that any subgroup within the Services even lukewarmly desired, but the Navy surface fleet had to proceed cautiously and indirectly to get it. 53 Furthermore, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research and Development, Tyler Marcy, stressed before procurement hearings in early 1977 that the Navy’s primary interest in the Tomahawk was the conventionally-armed anti-ship variant….

…Presidents facing a crisis are now just as likely to ask “where are the Tomahawks” as they are “where are the carriers?” Conventional Tomahawks are now considered one of the weapons of choice to make political statements against rogue states. When the Soviet Union crumbled and the Russian submarine threat diminished, conventional Tomahawks assured that submarines and surface combatants still had a role and were capable of meeting the new security challenges. In fact, this dispersed firepower was a primary reason the Naval Services were able to contemplate the new littoral warfare strategic vision detailed in … From the Sea …. 54

OSD Assumes Control

…Finally on 30 September 1977, Dr. William Perry, the new Director of Defense Research and Engineering, issued a memorandum to the Secretaries of the Air Force and Navy stating that because the ALCM flyoff was elevated to a matter “of highest national priority,” OSD would not allow the Air Force to continue to impede the creation of the Joint Cruise Missile Project Office (JCMPO) or its subsequent operation. 85 Perry directed that the present project management team be retained, that all Deputy Program Managers were to be collocated with the JCMPO, and that the JCMPO was a Chief of Naval Materiel Command-level designated project office. He once again directed the Air Force and Navy to allocate their entire cruise missile program funds directly to the JCMPO. In addition, Perry established an Executive Committee (EXCOM) to provide programmatic and fiscal direction with himself as chairman. 86 The original purpose of the EXCOM was to provide a forum for rapid review and discussion of problem areas and to build consensus concerning solutions. Dr. Perry, as the EXCOM chairman and now the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USDR&E; DDR&E’s new title), acted as the senior authority whenever it became necessary to resolve disputes between the Services. It was probably the only way to force Service acceptance of a truly joint program in the 1970s. 87

Thus within a span of a few months, management of cruise missile development evolved from one of Pentagon hindrance to one where the Under Secretary of Defense fostered rapid problem resolution. This probably wouldn’t have happened had not the ALCM emerged as a high national priority. 88 …Without Dr. Perry’s direct intervention, expeditious and fiscally efficient development of the cruise missile would not have occurred.

Final Political Notes

Like any other organizational endeavor, military activity is fraught with political machinations. In this case, segments of the military Services did not want cruise missiles because they threatened their missions and doctrine, as well as competed for scarce funding. “The long-range air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) was rammed down the throat of the Air Force. The Army refused to accept development responsibility for the ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM). The Navy – specifically the carrier Admirals – did not want the Tomahawk Anti-ship Missile because it represented a clear and present danger to the mission of the carrier-based aircraft.” 89 There was a “not invented here” mentality that was almost insurmountable among the Services. 90

Furthermore, the Air Force and Navy objected to a project manager who seemed to have been removed from their control. In order to streamline the cruise missile program, he was given direct communication links to the Under Secretary of Defense. This greatly facilitated program direction and allowed for rapid assimilation of technological breakthroughs. 91 However, the JCMPO also aggravated and alienated the Services which had now effectively lost control of both their funds and their programs. The program director immediately became an outsider. 92 The fact that the Navy and Air Force had completely different objectives also led to problems. “Anytime there’s not a consensus, the budgeteers, or budget analysts, will bore right in until they get two sides,” can demonstrate policy inconsistencies and then use them as justification to cut the budget. 93 Perry’s Executive Committee was established to ensure inconsistencies did not develop, but was not designed to be a rubber stamp group where Locke could go and receive approval by fiat. The EXCOM was a vehicle where concerned parties could come together and quickly get a decision on important issues. 94

Cruise missile development would not have proceeded as fast or gone as far had it not been for senior-level, civilian intervention bolstering the strong leadership provided by the Program Director. 95 Technological innovation abetted the development process, but by itself would not have created a self-sustaining momentum.

“At every crucial stage in the development of each type of cruise missile, high level political intervention was necessary either to start it or to sustain it,” particularly during the period from 1973 to 1977 when SALT II forced cruise missile advocates to bargain hard for systems which many in the military did not want…. 96

….Service mavericks and zealots were required as well. Admiral Locke was certainly one, and as director of the JCMPO, he became a strong advocate who was able to professionally guide cruise missile development. He was replaced in August 1982 by Admiral Stephen Hostettler. The Navy insisted the change was necessary because of poor missile reliability and schedule delays. 98 Naval leadership also wanted “their own man” in charge of the process. Because Admiral Locke had effectively bypassed naval leadership to overcome numerous problems, he was considered an outsider. In fact, Locke had been appointed because he was a good program manager and somebody whom OSD could trust. His unique power base automatically placed him at odds with the Navy. 99 On several occasions, Clements intervened to save Locke’s career because the Navy was trying to get rid of him. Locke was working on a program that wasn’t in the Navy mainstream and they feared the emergence of another Rickover. 100 Nevertheless, without Admiral Locke’s leadership, cruise missiles would not have been developed when they were.

1. Ronald Huisken, The Origin of the Strategic Cruise Missile (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1981), p. xiii.

2. Interview with RearAdmiral Walter M. Locke, USN, (Ret.), McLean, VA, 5 May 1993.

3. Interview with Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr., USN (Ret.), former Chief of Naval Operations, Washington, D.C., 28 May 1993.

4. Richard K. Betts, ed., Cruise Missiles: Technology, Strategy, Politics (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1981), p. 380. ADM Zumwalt’s predecessor, ADM Moorer, chose to respond to the Eilat incident by enhancing the capabilities of the carrier fleet, not those of the surface fleet. (Ibid., p. 384).

5. Zumwalt interview, 28 May 1993.

6. Betts, op. cit. in note 4, p. 84.

7. Locke interview, 5 May 1993.

19. Ibid., p. 30.

20. Kenneth P. Werrell, The Evolution of the Cruise Missile (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, 1985), p. 387.

21. Ross R. Hatch, Joseph L. Luber andJames W. Walker, “Fifty Years of Strike Warfare Research at the Applied Physics Laboratory,” Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest , Vol. 13, No. 1 (1992), p. 117.

22. Locke interview, 5 May 1993.

23. Interview with Vice Admiral James Doyle, USN, (Ret.), Bethesda, MD, 11 August 1993.

24. Admiral Locke greatly credits their vision and assistance during the early formation years of the cruise missile. Locke interview, 14 July 1993.

29. Interview with Vice AdmiralJoc Williams, USN, (Ret.), Groton, CT, 26 August 1993. The majority of the information in this paragraph is from this interview.

31. Admiral Zumwalt acknowledged in his book that Rickover and carrier aviation were impediments to his Project 60 plan throughout his tenure as CNO. [Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr., On Watch: A Memoir (New York: Quadrangle, 1976)] His apparent lack of advocacy for cruise missiles should not be misinterpreted. He used cruise missiles as a bargaining chip to obtain his higher goal of a balanced Navy which he felt was necessary to counter the Soviet threat. His threats to prevent Harpoon/cruise missile employment was merely a counter to Rickover’s “shenanigans,” as he referred to them.

32. Betts, op. cit. in note 4, p. 386. The Soviets eventually fielded their own large cruise missile submarine, the Oscar-class.

33. Werrell, op. cit. in note 20, p. 151 and Locke interview, 28 August 1994.

34. Locke interview, 5 May 1993. (Emphasis added).

35. Interview with the Honorable William P. Clements, former Deputy Secretary of Defense, Taos, NM, 16 June 1993.

36. Locke interview, 5 May 1993.

37. Interview with Dr. Malcolm Currie, former Director of Defense Research and Engineering, Van Nuys, CA, 21 September 1993.

45. Interview with Bob Holsapple, former Public Affairs and Congressional Relations Officer for the Tomahawk program, Alexandria, VA, 27 May 1993.

48. Rear Admiral Walter Locke’s testimony in Fiscal Year 1975 Authorization Hearings, pt. 7, pp. 3665-7.

49. ADM Zumwalt also saw the inclusion of SLCMs aboard surface ships as one final triumph over Rickover.

53. Betts, op. cit. in note 4, p. 406.

54. … From the Sea: Preparing the Naval Service for the 21st Century (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, September 1992).

85. Conrow, op. cit. in note 83, p. 6

86. Members of the EXCOM included DDR&E (chairman), the Assistant Secretary of the Navy (RE&S), the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (RD&L), the Vice Chief of Naval Operations, the Air Force Vice Chief of Staff, the Assistant Secretary of Defense (PA&E), and the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). After the first meeting, the Chief of Naval Operations, and the Commander Air Force Systems Command were added as permanent members. [Conrow, op. cit. in note 83, p. 14.]

87. Interview with Dr. William Perry, Secretary of Defense and former Director of Defense Research and Engineering, Newport, RI, 23 June 1993.

88. Conrow, op. cit. in note 83, p. 63.

89. Betts, op. cit. in note 4, p. 360.

90. Clements interview, 16June 1993. The Navy Secretariat’s reasonable belief was that OSD was using the Navy to develop an Air Force missile. This contributed to its “not invented here” attitude. [Locke interview, 28 August 1994].

91. Wohlstetter interview, 18 September 1993.

92. Naval personnel, such as Vice Admiral Ken Carr, who held positions outside of the Navy’s organization, were critical. Carr was Clements’ Executive Assistant and helped maintain backdoor channels for Locke that were as important, if not more important, than formal chains of command. Interview with Vice Admiral Ken Carr, USN, (Ret.), former Executive Assistant for William Clements, Groton Long Point, CT, 24 August 1993.

93. Interview with Mr. Al Best, SAIC, Alexandria, VA, 14 July 1993.

94. Perry interview, 23 June 1993.

95. Betts, op. cit. in note 4, p. 361.

96. Werrell, op. cit. in note 20, p. 361.

98. Werrell, op. cit. in note 20, p. 2 1 1 .

99. Currie interview, 21 September 1993.

100. Parker interview, 22 September 1993.

Featured Image: The battleship USS WISCONSIN (BB-64) launches a BGM-109 Tomahawk missile against a target in Iraq during Operation Desert Storm.

One thought on “The Politics of Naval Innovation: Cruise Missiles and the Tomahawk”

Greg shouid read American Defense Reform, 2022. Georgetown. Oliver and Toprani, pp 91-95 for a fuller picture of Zumwalt in Tomahawk.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Fostering the Discussion on Securing the Seas.

Canada's cruise missile testing controversy of 1983

Guidance system for u.s. weapon was to be tested in northern alberta.

Social Sharing

NDP External Affairs critic Pauline Jewett was steaming mad. Not just that an American weapon was going to be tested on Canadian soil, but at the Liberal cabinet's timing in announcing its decision.

"What a flabby performance! Isn't this typical? Parliament's not in session. Six o'clock on Friday afternoon they make the announcement... typical sleazy Liberal tactics!"

'We have a place in the West'

Two Liberal cabinet ministers, Allan MacEachen and Gilles LaMontagne, made no apologies for putting the word out just before a summer weekend on July 15, 1983.

As CBC Ottawa reporter Mike Duffy tells viewers, MacEachen said that as a western democracy, Canada had an obligation to do its share to help its allies. Offering a place for the cruise missile to be tested was part of Canada's commitment that alliance.

Besides, the testing was going to be in unpopulated northern Canada and the missile, which was designed to carry a nuclear warhead, would be unarmed. Moreover, it would do no damage to Canada or its people or the environment.

In the weeks and months following the announcement, there were public demonstrations and court challenges against testing of the cruise missile. In October 1984, an art student was jailed for defacing the Constitution , insisting it was "stained" already by the government's decision to allow cruise missile testing in Canada.

Testing of the cruise missile began in northern Alberta in March 1984.

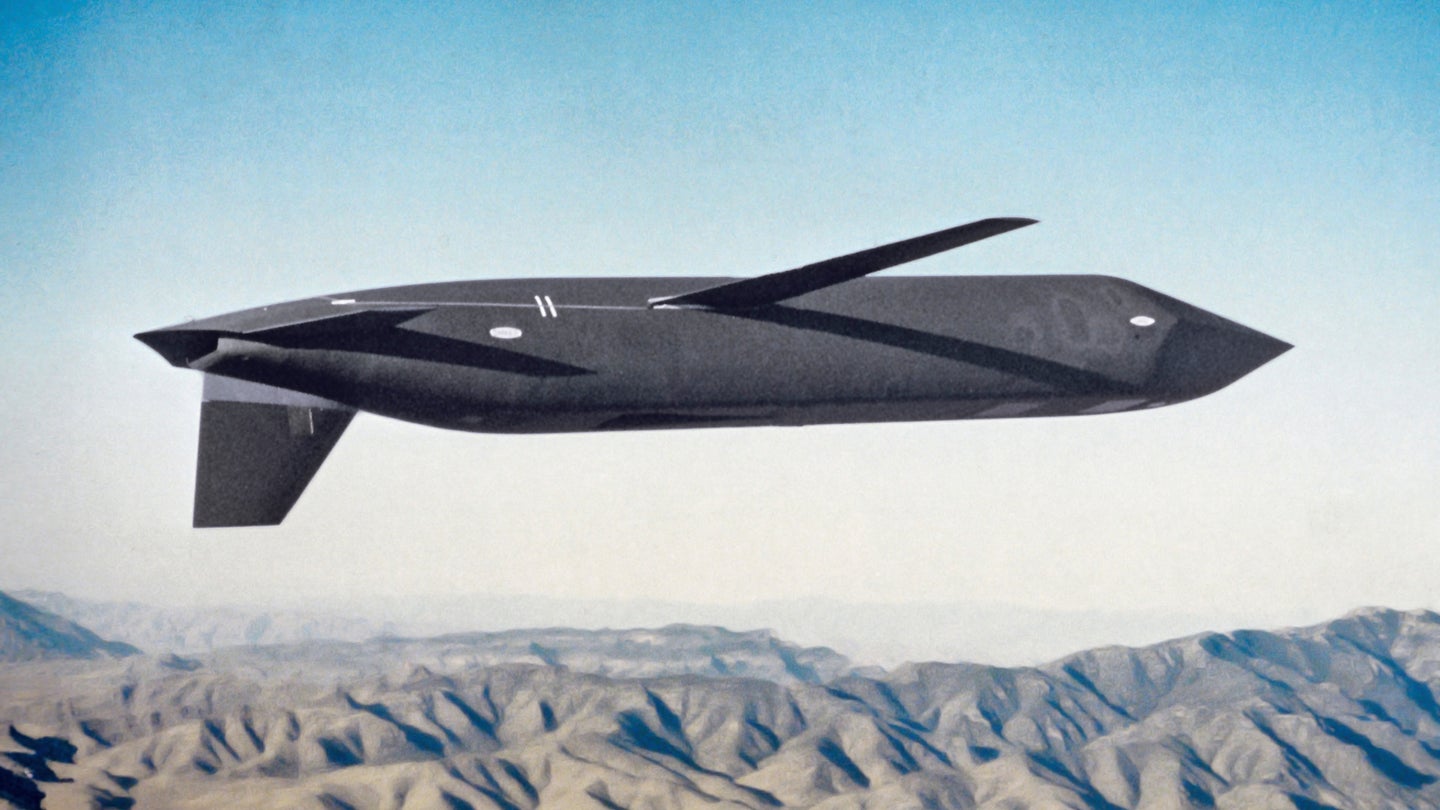

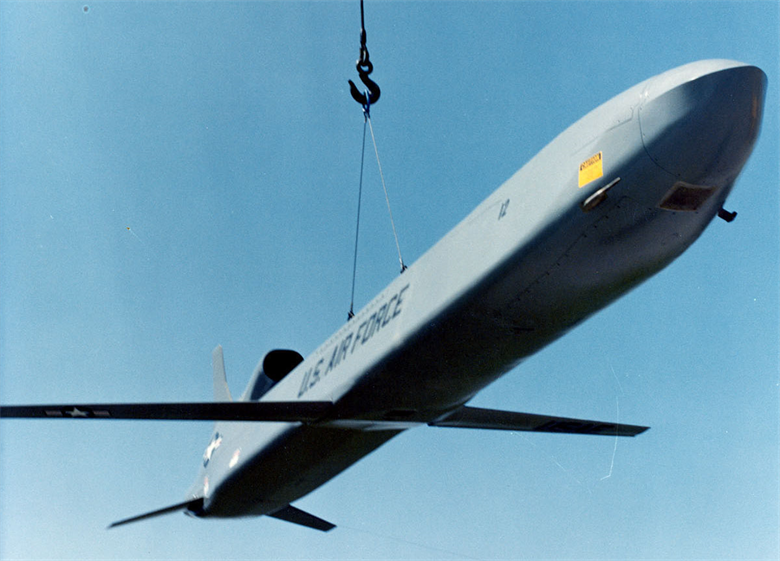

The Saga Of The AGM-129 Cruise Missile That Was Basically A Stealth Jet Designed Upside Down

The Advanced Cruise Missile was too far ahead of its time, so much so that it was eventually succeeded by the missile it was supposed to replace.

Aviation_Intel

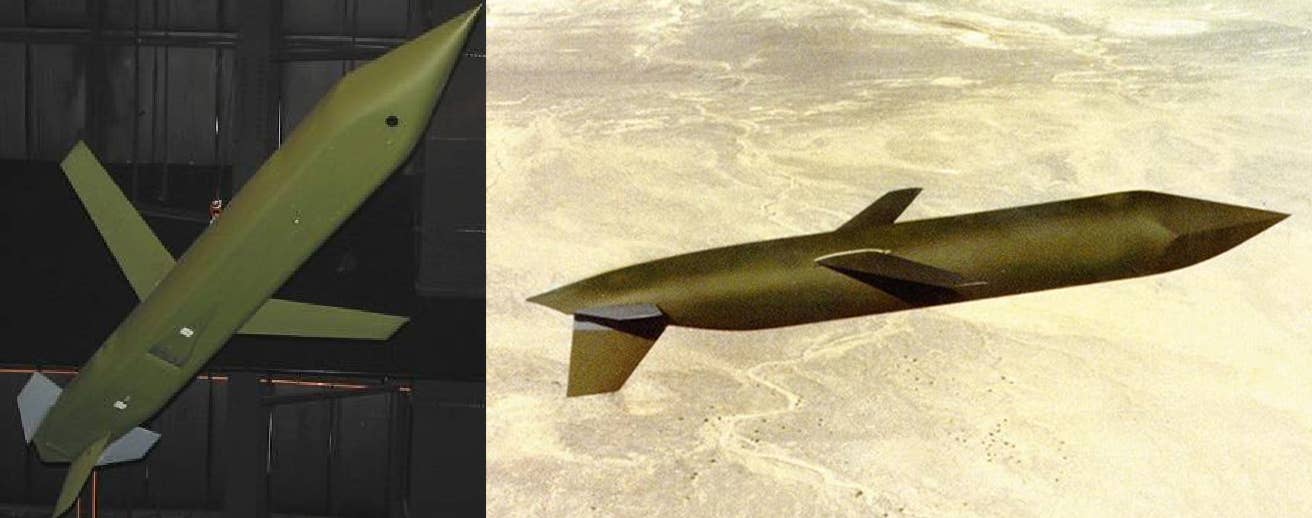

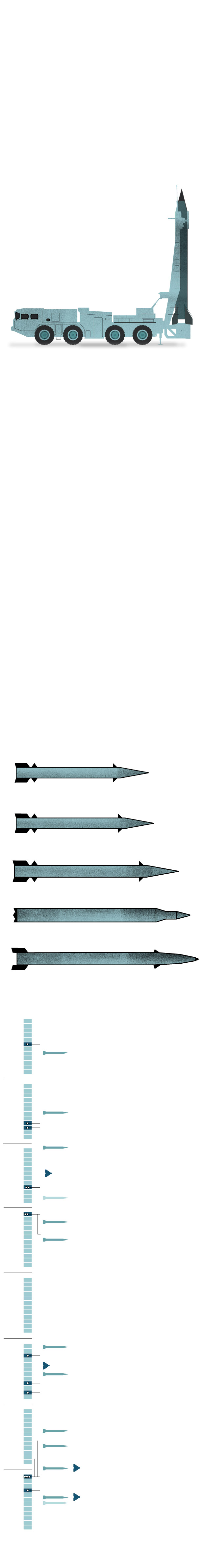

Most people would be surprised to hear that the most advanced nuclear-tipped cruise missile ever put into operation was retired from service while its predecessor, a less survivable missile it was supposed to replace, soldiers on in U.S. Air Force service to this very day. This topsy-turvy reality is somewhat metaphorical of General Dynamics' AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM) itself. In fact, the AGM-129 could be considered the second stealth aircraft to ever enter production, because that is what it really was, albeit one that was designed upside down, and for good reason.

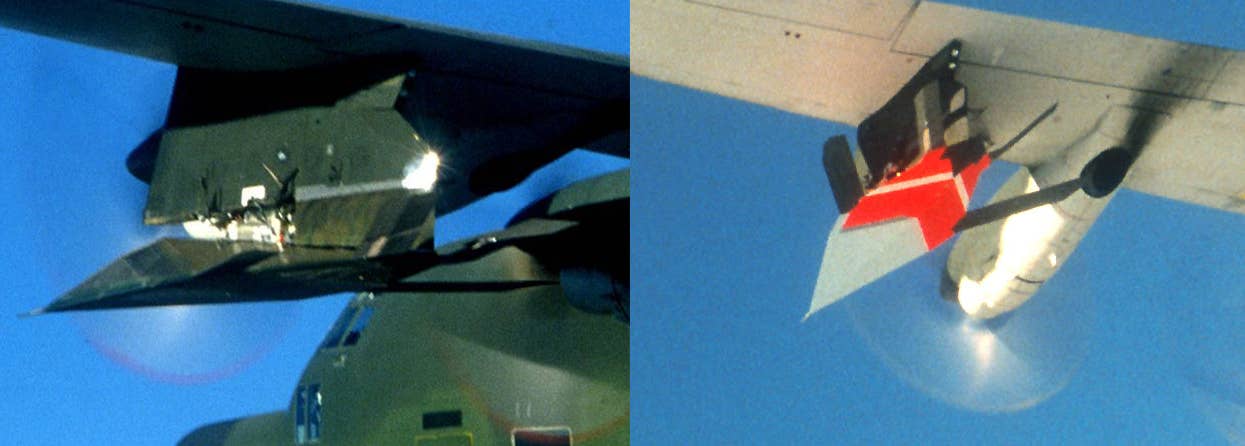

The origins of the ACM are fairly straightforward. The AGM-86B Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) entered service in the early 1980s. When it was being designed, and while the non-production AGM-86A was undergoing initial trials, the best way to deliver a nuclear warhead deep inside Soviet airspace by an air-breathing platform was via low-altitude penetration . The AGM-86 was designed exactly for that, to punch through at treetop level using terrain contour matching , terrain-following radar, and inertial navigation to get close enough to a target that the W80 nuclear warhead onboard could do its job successfully.

Later on, the AGM-86C and D would integrate GPS to deliver pinpoint conventional strikes. You can read all about the AGM-86C/D's capabilities in this recent piece of ours , but the nuclear-armed version of the era had no such accuracy. Regardless, survivability against quickly evolving Soviet air defenses was the most pressing requirement in the Air Force's air-launched cruise missile portfolio as the 1970s gave way to the 1980s.

The AGM-86B had a few stealthy characteristics, but it was far from a true low observable design. Just as it came into service, the Air Force realized that the days when being able to beat air defenses via low-flying alone were coming to an end. Airborne early warning and control aircraft and advanced fire control radars with look-down-shoot-down capabilities, like those on Russia's 4th generation fighter and interceptor fleets (Su-27 and MiG-31, specifically), would decrease the effectiveness of nap-of-the-earth flying tactics. Something far more survivable was needed, and fast.

Out of a handful of DARPA initiatives and studies dubbed TEAL DAWN that explored future cruise missile technologies and long-range bomber strategies, it was concluded that the new stealth bomber then in development alone wouldn't be survivable against the densest Soviet air defenses. Long-range and survivable standoff weapons would be needed in part to mitigate those defenses. Two requirements were established—one stealthy missile that could travel around 1,500 miles or more and another that could travel over 5,000 miles. The latter clearly invalidated much of the need for a stealth bomber in the first place and it was thought that at least a decade would be needed to develop such a long-range weapon. As a result, it was jettisoned to concentrate on the shorter-ranged stealthy cruise missile requirement that could be fielded quickly and equip the Air Force's new stealth bomber—at least that's what they hoped. With this in mind, a competition to build such a weapon was quietly launched.

Lockheed, Boeing, and General Dynamics ended up squaring off in secret for this new contract. Lockheed's Skunk Works leveraged their work on the F-117 program, which was just spinning up in a very secretive operational state at the time , to produce its F-117-shaped cruise missile, known under the code name SENIOR PROM. The details surrounding Boeing's design remain unclear. General Dynamics' design was a bit more of a traditional configuration, but one that was clean-sheet and packed with very stealthy features arranged in unique ways to maximize its effectiveness and efficiency. SENIOR PROM, which was a test program before competing for the Advanced Cruise Missile contract, was very stealthy, but it would have been troublesome fitting it into a bomber's weapons bay. By 1983, General Dynamics clenched the contract and the AGM-129A Advanced Cruise Missile was officially born.

General Dynamics' design, which measured nearly 21 feet long and weighed in at 3,700 pounds, was downright wicked looking. A faceted, stiletto-shaped fuselage with a chined, sharp-tip nose area and forward-swept pop-out wings gave it a sinister, almost Klingon-like look. Not just the wings were backward, all the low observable features were oriented towards defeating detection from above , not below. This resulted in an upside-down-looking airframe of sorts.

The vertical stabilizer-rudder pointed down instead of up. It was made up of composite materials, as were the missile's horizontal forward-swept stabilizers, to remain nearly invisible to the most threatening radar bands. The vertical stabilizer was also offset to the left side of the fuselage's centerline.

That gas from the missile's two-dimensional exhaust aperture was blown over a platypus-like defuser structure that shielded its signature from, you guessed it, above, instead of below. The exhaust was also mixed with cold air to help further attenuate its infrared signature. Soviet infrared search and track (IRST) systems were advancing in capability at the time and included on all of Russia's 4th generation fighter/interceptor designs, so infrared signature reduction was weighted heavily alongside radar cross-section reduction during the competition that led to the AGM-129.

The low-observable trapezoidal air inlet sat flush on the bottom of the missile instead of the top of it and fed the engine with air through a serpentine duct, thus eliminating any radar return from the engine fan face. Realizing a flush air inlet on something that flies at transonic speeds comes with major design challenges and it's not like any stealthy air inlet configuration is easy to design or produce , to begin with. Beyond its underlying radar-evading structures , the AGM-129 was also covered with radar absorbent material and coatings and given an olive drab color to blend in with the terrain it would roar over just before sparking off a nuclear apocalypse.

So, if you think the AGM-129 looks like it is flying inverted, that is by very conscious design. Overall, the missile was designed with a particular weight put on stealth from its upper and forward aspects, where it was most vulnerable. From directly to its side, its radar signature was reduced, but more visible than from other angles. This was deemed a non-issue because the pulse-doppler radars that could threaten it from above are unable to detect low-flying targets hiding in ground clutter while flying at perpendicular angles to the radar antenna as they remain inside the radar's "doppler notch." You can read more about this phenomenon and the tactics associated with it here.

Navigation was also innovative. The AGM-129 introduced a laser doppler velocimeter into its navigational suite, which, like the AGM-86, also included inertial navigation and terrain contour matching. This gave it substantially better accuracy over long distances than the AGM-86B, which was designed less than a decade before it.

It also included laser detection and ranging system (LADAR) to aid in low-altitude flight, which further allowed it to fine-tune its endgame attack run down to as accurate as 90 feet according to stated metrics, although the system likely became even more accurate as it matured. Considering it still packed the same W80 variable yield warhead (5kt-150kt) as the AGM-86B, its better accuracy substantially increased its effectiveness, especially against reinforced targets or those that are partially shielded by terrain.

LADAR, as opposed to radar, also allowed the AGM-129 to remain electromagnetically silent, giving off no radio frequency energy when it was most vulnerable and thus making it even harder to detect. There were some tradeoffs though, LADAR could have trouble receiving data against certain surfaces, such as those that were extremely reflective or highly light absorbent. Still, the system was extremely effective and because the missile was so stealthy, it could fly at higher altitudes and in most cases still survive to make it to its target if need be.

Still, the system was not perfect. During one test over Dugway Proving Ground in 1997, an AGM-129 was flying so low it impacted some trailers belonging to an observatory. Nobody was hurt in the incident and the missile had been flying for three and a half hours before the accident. It turns out the mission planners had no idea the trailers were there and how the missile got so low was unclear to begin with.

The missile was fast, traveling at just under the speed of sound, and it also packed a very long range. It used a far more fuel-efficient engine, the Williams International F112-WR-100 turbofan, than the one found on the AGM-86, which gave it significantly greater range while retaining similar dimensions and the same payload. Officially, ACM could reach out 2,000 miles to its target , but it seems clear that its real range was actually significantly further, especially when flying a more efficient flight profile during more benign portions of its trip to its target area. As noted earlier, the missile's high degree of stealth meant that it could climb to more efficient altitudes during certain phases of flight and still have a high chance of surviving to complete its horrific task.

Another interesting component of the AGM-129 was its computer system. From how it has been explained to me it used basically one central processor and computing system to run the vast majority of the missile's functions. For early 1980s military technology, this is an amazing feat. Basically, the computer system and the system designed to used it on the missile was absolutely cutting-edge for its time.

It can't be stressed enough how advanced the ACM was for its time. It had many elements that hadn't yet emerged from the classified manned aircraft realm, but was an autonomous system meant to fly thousands of miles to its target without aid and to be built by the hundreds. It was truly a highly sensitive modern marvel of its era.

The first flight test of an AGM-129 occurred in July of 1985, with the first production missiles being delivered two years later, in 1987. It was that year when the program became public, as well. In that sense, it was the first disclosure of a stealth flying machine ever. Still, the program struggled early in its production run. There were technological issues that popped up in flight testing, but the major problems were with building the advanced missiles themselves. Remember, at the time of its first deliveries, no stealth aircraft had even been acknowledged by the Air Force. This wouldn't occur until two years later when the F-117 was officially disclosed to the public. So, the technologies used in its manufacturing were absolutely cutting-edge in nature.

The missile's very aggressive concurrent testing and production schedule concept and major labor issues with the International Association of Machinists began to cripple the program and it quickly became a pariah on Capitol Hill and in certain parts of the Pentagon. By the end of the decade, the AGM-129 was being declared a fiasco. Things got so bad with quality control issues that production was halted between 1989 and 1991.

Of course, the timing of this setback couldn't have been worse. The Cold War was ending and the defense budget was set to snap back hard, especially in terms of strategic weaponry. In addition, the B-2 wouldn't fly until 1989 and still would have a long developmental road ahead of it. The B-1B was also having its own troubles and the missile was never designed to fit in its weapons bays , it was too long, and eventually, the B-1B would lose its nuclear role altogether. So, the weapon that was procured at least in part to be paired with the stealth bomber would be relegated to the B-52.

The confluence of these factors, as well as the START treaty which limited these types of weapons, resulted in a drastic reduction of the programmed buy. The nearly 1,500 missiles needed to replace the AGM-86B in full was slashed down to less than half that, and eventually to a final number of just 460 missiles. Unit cost soared partially as a result of the curtailed order, with each missile costing roughly $4.3 million in 1992 dollars. This is extremely expensive for a cruise missile even by today's standards. A decade earlier, the AGM-86Bs cost around $1.3 million each. The ACM had truly entered a Pentagon budgetary 'death spiral' alongside the plane that was supposed to carry it, the B-2.

Still, they were the most advanced cruise missiles in the world and the truncated force of 460 missiles soldiered on over the next two decades, exclusively equipping the B-52 force. A single B-52 could carry 20 of the missiles at one time. Six on each wing pylon and eight in the jet's cavernous weapons bay on a rotary launcher.

Two other AGM-129 variants were proposed, but never came to fruition. The AGM-129B was a shadowy initiative to equip a revised design with an axial-flow jet engine, new software, and a different nuclear warhead to take on a specialized role that remains classified. This could have been a GPS-equipped, imaging infrared, or otherwise more precise upgrade of the weapon that would also be equipped with a penetrating nuclear warhead of a lower yield to take on heavily fortified bunkers and more hardened structures. Then again, maybe it was something more exotic, we just don't know for absolute certain.

The other proposed variant was a conventional land attack model similar to the AGM-86C/D Conventional Air-Launched Cruise Missiles (CALCM), but far more survivable and with a lot longer reach. GPS would have been necessary for this weapon, just like it was for its CALCM progenitor. An imaging infrared seeker with imaging matching could have been injected into the design for even better accuracy. In retrospect, this would have been a relatively amazing weapon.

The ACMs that were built may have received a GPS upgrade sometime during the decade and a half or so that followed their introduction into service in 1990, although it remains unclear if this actually happened. It would have given the missiles pinpoint accuracy, but GPS connectivity would not be assured during a nuclear war and it may have been cost-prohibitive to integrate a GPS antenna onto the ACM's stealth airframe. If the upgrade did happen, it would have likely occurred when the missiles were put through a Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) in the early 2000s that would allow them to serve until 2030 and possibly beyond.

Regardless of this life extension program, in 2007, the 17th year of the AGM-129's operational service, it was decided that the entire ACM force would be drawn down and eliminated from service by the end of 2012. A number of factors contributed to this decision, the first being the post 9/11 focus on counter-insurgency operations instead of preparing for peer state conflicts. The U.S. had two raging wars on its hands that were anything but cheap, and the Russian bear remained largely dormant at the time, while China was just on precipice its economic, geopolitical, and technological rise. The AGM-129 program, with its relatively small fleet made up of super high-tech 1980s technology, meant that sustaining the missiles was far from a cheap or easy task. The AGM-86B, although much less survivable, checked a box for much less money and had commonality with its conventionally armed cousin, the AGM-86C/D, which helped significantly in terms of sustainment scalability.

Beyond fiscal matters, the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) with Russia also meant more warheads would be pulled off the front lines. So, the Air Force moved forward with not just retiring the AGM-129, but destroying the fleet, a task that was completed as planned by the end of 2012.

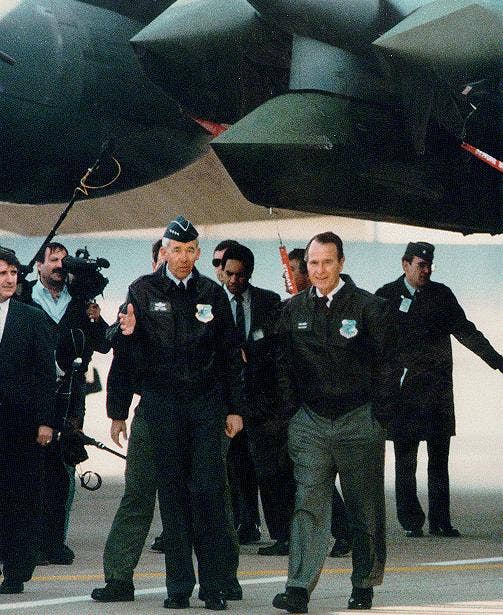

During its drawdown period, one highly publicized and unfortunate event occurred with what were historically very shy missiles. On August 30th, 2007 a "Bent Spear" incident occurred with a package of 12 ACMs. A B-52H was set to ferry unarmed ACMs from Minot AFB in North Dakota to Barksdale AFB in Louisiana. The missiles were to be decommissioned at Barksdale, so the mission itself wasn't necessarily out of the ordinary. What was not normal is that six of the missiles were actually carrying their W-80 thermonuclear warheads.

The nuclear-armed B-52 sat overnight without a proper security detail and other precautions until the crew showed up for the mission the next day. During pre-flight checks, the crew did not inspect both pylons loaded with missiles. They only inspected the one that held six unarmed ACMs, but logged that both pylons full of missiles were indeed checked and that they were unarmed. The crews then flew across the Midwest not knowing they were carrying six nuclear warheads.

After arriving at Barksdale, the jet sat for another eight hours without standard precautions associated with nuclear-armed aircraft. It was nearly a day and a half after the Minot AFB personnel blew off normal procedures and loaded the hot ACMs on the B-52 that the fact that the plane was actually carrying live warheads was discovered. The incident was the first of its kind in four decades and sent shockwaves through the Air Force and the Pentagon. A subsequent investigation showed horrible disregard for critical nuclear weapons handling protocols and everyone from four unit commanders down to those directly involved were heavily disciplined or removed from duty. All nuclear weapons handling was suspended at Minot AFB. It also resulted in a new set of procedures that were designed to make sure such a breakdown in procedures doesn't happen again.

It was a sad end to the troubled development and career of the world's first stealth cruise missile.

In retrospect, the decision not just to retire, but fully destroy the AGM-129 cadre seems like a very poor one. Today, the Air Force is working on developing a new stealthy long-range nuclear-tipped cruise missile, the Long-Range Stand-Off (LRSO) weapon, a program that will cost tens of billions of dollars and won't produce an operational missile until at least 2030. Raytheon, which owns the AGM-129 design after it bought Hughes Missile Systems, which bought General Dynamics' missile portfolio prior, is competing with Lockheed for the LRSO contract. In the meantime, the AGM-86B is supposed to remain a viable deterrent even in an era of ever more capable highly integrated air defense systems, ones that now rely on look-down-shoot-down sensors more than they did 35 years ago and that are far more advanced in general than what existed when ACM was conceived. This begs the question, is the AGM-86B really a survivable deterrent at all? The true answer, that we will never officially get, is probably less comforting than we may want to hear.

The truth is, the AGM-129 was way ahead of its time. Today, there are numerous stealthy cruise missiles in production or will be in production soon and they are becoming an extremely sought-after item. The USAF can't get enough of Lockheed's JASSM family of missiles , which continues to rapidly grow in capability, while the Navy is procuring the anti-ship LRASM cousin of JASSM, the stealthy Naval Strike Missile , and a powered version of the JSOW. Multiple foreign militaries have their own stealthy cruise missiles , as well. But these are conventionally armed weapons. It will be at least another decade until a nuclear-armed stealth cruise missile hits the USAF's inventory again. That weapon, the LRSO, will be in many ways the son of AGM-129 and from what we are hearing, it will be absolutely loaded with the latest and greatest technology that will allow it to survive in the most inhospitable of combat environments. It is also meant to equip the USAF's new stealth bomber, the B-21 Raider.

Somehow this all sounds eerily familiar, doesn't it?

Contact the author: [email protected]

- Our Purpose

- Ambassador Robert S. Strauss

- Ambassador Strauss Archive

- Cybersecurity

- Technology, Security, and Global Affairs

- Space Security, Safety, and Sustainability

- Joint Studies Program

- Cyber Student Fellows

- Energy and Security

- Artificial Intelligence

- Central America and Mexico Policy Initiative

- Asia Policy Program*

- Post-Soviet States

- State Fragility

- Armed and Social Conflict

- Complex Emergencies in Asia

- Climate Change and Africa

- *With the Clements Center

- Intelligence Studies Project*

- Journalism and World Affairs

- National Security Law

- Baker Chair Transatlantic Dialogues

- Mike Lewis Prize for National Security Law Scholarship

- Texas National Security Review*

- National Security Law Student Fellows

- Brumley Graduate Fellows

- Brumley Undergraduate Scholars

- Horns of a Dilemma Podcast*

- National Security Law Podcast

- Texas National Security Forum*

Strait of Hormuz

Assessing the threat to oil flows through the strait.

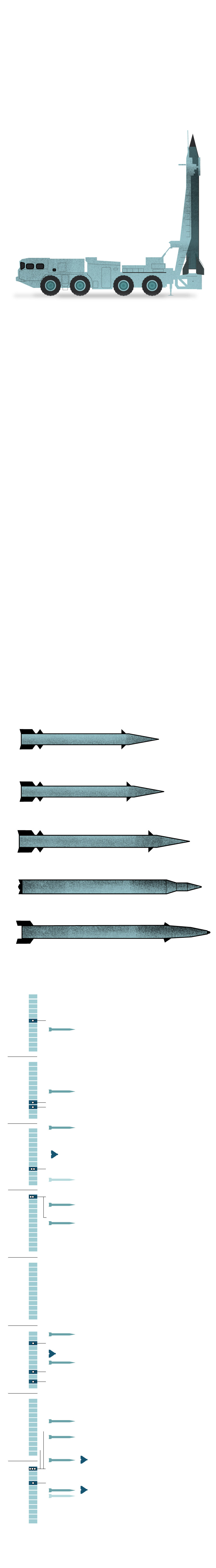

Anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) are modern long-range weapons of naval combat, designed specifically to target ships. Due to their stealth, accuracy, and low-cost, ASCMs have become weapon of choice for militaries around the world. ASCMs were used in over half of attacks on merchant shipping by Iran and Iraq during the Tanker War .[i]

Iran reportedly has acquired hundreds of ASCMs that they could likely use to try to disrupt oil flows through the Strait.

How ASCMs Work

Relevant historical use of ascms.

- Iran & ASCMs

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Exocet-mil.jpg

Caption: An Exocet missile fired from a land-based launcher

In order for an ASCM to function properly, it must perform the following sequence correctly:

Some ASCMs locate their targets using radar. This technique requires the launcher to have a line of sight to the target, limiting the range of the missile to the radar horizon and preventing the missile from seeing a target that is hidden by any terrain obstacles. Furthermore, simple scanning radars cannot determine the difference between cargo, container, and oil tanker ships, all of which can be of similar size.

Missiles that locate their targets using scanning radars also emit radio waves, revealing their position. This limits the utility of these missiles in asymmetric warfare: once the launcher reveals its location, it is vulnerable to attack by the adversary's conventional forces.

During the Cold War, the superpowers developed another targeting method, "over-the-horizon targeting," mostly in an effort to expand the range of their missiles. In this technique, a launch technician either programs a missile's flight path or a set of target coordinates, and the missile simply flies to the target area. Over-the-horizon targeting requires a spotter to relay the target coordinates to the shooter, but the shooter need not actually be able to see the target himself. This targeting method has become considerably easier to use in recent years due to the ubiquity of GPS navigation devices.

A booster kit propels the missile from the launch platform to an adequate speed and altitude to enable the missile to transition to the cruise flight mode.