- Emmy Award nominees

- ASCAP Film and Television Music Award winners

- Documentary staff

Dennis McCarthy

- View history

McCarthy and Jay Chattaway

Dennis McCarthy ( born 3 July 1945 ; age 78) is a composer who has written many Star Trek -related musical scores, including the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine main title theme and the Star Trek: Enterprise end credits theme. He also composed the music for Star Trek Generations and many episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation , Star Trek: Deep Space Nine , Star Trek: Voyager and Star Trek: Enterprise . He scored the pilots and finales of Star Trek: The Next Generation , Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Star Trek: Enterprise . McCarthy also wrote and conducted the music for the Star Trek: The Experience movie Borg Invasion 4D and the computer game Star Trek: Borg . Some of McCarthy's TNG and DS9 scores were released as part of the Star Trek: The Next Generation Collection, Volume One and the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Collection .

McCarthy was nominated for nine Emmy Awards for his work, winning in the "Outstanding Individual Achievement in Main Title Theme Music" category for his Deep Space Nine title theme. He also won (or shared) nine ASCAP Awards , all for "Top TV Series" except for his award for Star Trek Generations , which won in the "Top Box Office Films" category.

McCarthy was once a member of Dick Dale 's backing band, which came up while he was scoring the episode " Vis à Vis " which featured two Dick Dale tunes, " Night Rider " and " Let's Go Trippin' ". Ronald B. Moore suggested the first song and remembered, " I was told that [McCarthy] heard the music and said, 'I used to be a Deltone.' This is a small world. He suggested that they close the show with another Dick Dale song. They got to [do that]. " ( Cinefantastique , Vol. 30, No. 9/10, p. 103)

McCarthy started his career as music arranger and moved shortly after this to the position of music composer. His first assignment was the television spinoff series Enos (1980-1981), followed by the series Private Benjamin (1982), Gun Shy (1983), Goodnight, Beantown (1983-1984), and The Barbara Mandrell Show . In early 1984, McCarthy was asked to redo the score for the second and the third part of the television mini series V: The Final Battle , just two weeks before the airdate. His successful scoring for V: The Final Battle including the "Visitor March" lent him to the assignment scoring the following television series V (1984-1985) as well as projects such as Trapper John, M.D. (1986), The Love Boat (1986), Mike Hammer (1986), The Colbys (1985-1987), The Twilight Zone (1986-1987), Dynasty (1985-1989), Falcon Crest (1989), and MacGyver (1985-1991).

- 2 Star Trek credits

- 3 Awards for Star Trek

- 4 Star Trek interviews

- 5 External links

- DS9 Main Title Theme (seasons 1-3) file info

- DS9 Main Title Theme (seasons 4-7) file info

Star Trek credits [ ]

- " Encounter at Farpoint " ( Season 1 )

- " The Last Outpost "

- " Justice "

- " Hide And Q "

- " The Big Goodbye "

- " Angel One "

- " Home Soil "

- " Coming of Age "

- " The Arsenal of Freedom "

- " Symbiosis "

- " Conspiracy "

- " The Child " ( Season 2 )

- " Elementary, Dear Data "

- " The Schizoid Man "

- " Unnatural Selection "

- " The Measure Of A Man "

- " The Dauphin "

- " Contagion "

- " Time Squared "

- " Pen Pals "

- " Samaritan Snare "

- " Manhunt "

- " Peak Performance "

- " The Ensigns of Command " ( Season 3 )

- " The Survivors "

- " The Bonding "

- " The Enemy "

- " The Vengeance Factor "

- " The Hunted "

- " Yesterday's Enterprise "

- " Sins of The Father "

- " Captain's Holiday "

- " Hollow Pursuits "

- " The Most Toys "

- " Transfigurations "

- " Family " ( Season 4 )

- " Suddenly Human "

- " Future Imperfect "

- " The Loss "

- " The Wounded "

- " Galaxy's Child "

- " Identity Crisis "

- " Half a Life "

- " The Mind's Eye "

- " Redemption "

- " Redemption II " ( Season 5 )

- " Ensign Ro "

- " Disaster "

- " Unification I "

- " Unification II "

- " New Ground "

- " Violations "

- " Conundrum "

- " Cause And Effect "

- " Cost Of Living "

- " Imaginary Friend "

- " The Next Phase "

- " Time's Arrow "

- " Time's Arrow, Part II " ( Season 6 )

- " Man Of The People "

- " Schisms "

- " Rascals "

- " The Quality of Life "

- " Ship In A Bottle "

- " Tapestry "

- " Lessons "

- " Suspicions "

- " Second Chances "

- " Timescape "

- " Liaisons " ( Season 7 )

- " Phantasms "

- " Attached "

- " Force of Nature "

- " Parallels "

- " Homeward "

- " Thine Own Self "

- " Genesis "

- " Firstborn "

- " Bloodlines "

- " All Good Things... "

- Main title theme (all episodes)

- " Emissary " ( Season 1 )

- " Captive Pursuit "

- " The Passenger "

- " Move Along Home "

- " Battle Lines "

- " The Storyteller "

- " The Forsaken "

- " In the Hands of the Prophets "

- " The Homecoming " ( Season 2 )

- " The Circle "

- " The Siege "

- " Invasive Procedures "

- " Rules of Acquisition "

- " Second Sight "

- " Sanctuary "

- " The Alternate "

- " Whispers "

- " Paradise "

- " Playing God "

- " Blood Oath "

- " The Maquis, Part II "

- " The Wire "

- " Crossover "

- " The Jem'Hadar "

- " Meridian " ( Season 3 )

- " Fascination "

- " Past Tense, Part I "

- " Life Support "

- " Destiny "

- " Prophet Motive "

- " Distant Voices "

- " The Die is Cast "

- " Explorers "

- " The Way of the Warrior " ( Season 4 )

- " The Visitor "

- " Indiscretion "

- " Homefront "

- " Crossfire "

- " Accession "

- " Hard Time "

- " Shattered Mirror "

- " Body Parts "

- " Apocalypse Rising " ( Season 5 )

- " Nor the Battle to the Strong "

- " Trials and Tribble-ations "

- " Rapture "

- " For the Uniform "

- " In Purgatory's Shadow "

- " Doctor Bashir, I Presume "

- " A Simple Investigation "

- " Blaze of Glory "

- " A Time to Stand " ( Season 6 )

- " Behind the Lines "

- " You Are Cordially Invited "

- " The Magnificent Ferengi "

- " Far Beyond the Stars "

- " Change of Heart "

- " Inquisition "

- " The Reckoning "

- " The Sound of Her Voice "

- " Image in the Sand " ( Season 7 )

- " Shadows and Symbols "

- " Once More Unto the Breach "

- " Prodigal Daughter "

- " The Emperor's New Cloak "

- " Inter Arma Enim Silent Leges "

- " Penumbra "

- " Extreme Measures "

- " What You Leave Behind "

- " Parallax " ( Season 1 )

- " Eye of the Needle "

- " Ex Post Facto "

- " State of Flux "

- " Heroes and Demons "

- " Elogium "

- " The 37's "

- " Initiations " ( Season 2 )

- " Parturition "

- " Cold Fire "

- " Resistance "

- " Alliances "

- " Dreadnought "

- " Deadlock "

- " Resolutions "

- " Basics, Part I "

- " False Profits " ( Season 3 )

- " Basics, Part II "

- " The Swarm "

- " The Q and the Grey "

- " Macrocosm "

- " Favorite Son "

- " Real Life "

- " Worst Case Scenario "

- " The Gift " ( Season 4 )

- " Day of Honor "

- " The Raven "

- " Year of Hell "

- " Year of Hell, Part II "

- " Concerning Flight "

- " Vis à Vis "

- " Living Witness "

- " Hope and Fear "

- " Drone " ( Season 5 )

- " Nothing Human "

- " Timeless "

- " Infinite Regress "

- " Gravity "

- " The Disease "

- " Juggernaut "

- " Someone to Watch Over Me "

- " Relativity "

- " Survival Instinct " ( Season 6 )

- " Tinker Tenor Doctor Spy "

- " The Voyager Conspiracy "

- " Tsunkatse "

- " Virtuoso "

- " Ashes to Ashes "

- " Life Line "

- " Unimatrix Zero "

- " Unimatrix Zero, Part II " ( Season 7 )

- " Critical Care "

- " Body and Soul "

- " Lineage "

- " Workforce "

- " Workforce, Part II "

- " Natural Law "

- " Renaissance Man "

- Archer's Theme (Closing credits) (all episodes)

- " Broken Bow " ( Season 1 )

- " Strange New World "

- " Breaking the Ice "

- " Fortunate Son "

- " Sleeping Dogs "

- " Shockwave "

- " Shockwave, Part II " ( Season 2 )

- " Dead Stop "

- " The Communicator "

- " Future Tense "

- " Cogenitor "

- " The Expanse "

- " The Xindi " ( Season 3 )

- " Impulse "

- " Twilight "

- " Carpenter Street "

- " Doctor's Orders " (with Kevin Kiner )

- " Damage " (with Kevin Kiner)

- " Countdown " (with Kevin Kiner)

- " Storm Front, Part II " ( Season 4 ) (with Kevin Kiner)

- " Borderland " (with Kevin Kiner)

- " Kir'Shara "(with Kevin Kiner)

- " Observer Effect " (with Kevin Kiner)

- " The Aenar " (with Kevin Kiner)

- " In a Mirror, Darkly " (with Kevin Kiner)

- " In a Mirror, Darkly, Part II " (with Kevin Kiner)

- " These Are the Voyages... " (with Kevin Kiner)

- DIS : " Kobayashi Maru " (Archer's Theme, uncredited)

- LD : " Hear All, Trust Nothing " (Theme from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine , uncredited)

- PIC : " The Bounty " (Theme from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine , uncredited)

- Star Trek Generations

- What We Left Behind

Awards for Star Trek [ ]

McCarthy received the following awards and nominations for his work on Star Trek :

- 1989 Emmy Award nomination in the category Outstanding Achievement in Music Composition for a Series (Dramatic Underscore) for the episode " The Child "

- 1990 Emmy Award nomination in the category Outstanding Achievement in Music Composition for a Series (Dramatic Underscore) for the episode " Yesterday's Enterprise "

- 1991 Emmy Award nomination in the category Outstanding Achievement in Music Composition for a Series (Dramatic Underscore) for the episode " Half a Life "

- 1992 Emmy Award nomination in the category Outstanding Individual Achievement in Music Composition for a Series (Dramatic Underscore) for the episode " Unification I "

- 1993 Emmy Award in the category Outstanding Individual Achievement in Main Title Theme Music for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

- 1994 Emmy Award nomination in the category Outstanding Individual Achievement in Music Composition for a Series (Dramatic Underscore) for the episode " All Good Things... "

- 1995 Emmy Award nomination in the category Outstanding Individual Achievement in Music Composition for a Series (Dramatic Underscore) for the episode " Heroes and Demons "

- 1995 ASCAP Award in the category Top TV Series for Star Trek: The Next Generation

- 1995 ASCAP Award in the category Top Box Office Films for Star Trek Generations

- 1996 ASCAP Award in the category Top TV Series for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

- 1997 ASCAP Award in the category Top TV Series for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

- 1998 ASCAP Award in the category Top TV Series for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine , shared with Jay Chattaway

- 1999 ASCAP Award in the category Top TV Series for Star Trek: Voyager

- 2000 ASCAP Award in the category Top TV Series for Star Trek: Voyager

- 2001 Emmy Award nomination in the category Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (Dramatic Underscore) for the episode " Workforce "

- 2001 ASCAP Award in the category Top TV Series for Star Trek: Voyager , shared with Jay Chattaway and David Bell

- 2002 ASCAP Award in the category Top TV Series for Star Trek: Enterprise , shared with Jay Chattaway, David Bell, Paul Baillargeon , and Diane Warren

- 2003 Emmy Award nomination in the category Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (Dramatic Underscore) for the episode " The Expanse "

Star Trek interviews [ ]

- "Dennis McCarthy – Music of the Stars", The Official Star Trek: The Next Generation Magazine issue 14 , pp. 5-10, interviewed by David Hirsch

- TNG Season 2 DVD special feature "Departmental Briefing Year Two: Production" ("Music"), interviewed on 5 October 2001

- TNG Season 7 DVD special feature "Starfleet Moments & Memories Year Seven" ("A Unique Family"), interviewed on 5 October 2001

- In Conversation: The Music of Star Trek - The Next Generation ( 2013 )

External links [ ]

- Dennis McCarthy at Wikipedia

- Dennis McCarthy at the Internet Movie Database

- 2 ISS Enterprise (NCC-1701)

- Nov 2, 2023

Star Trek’s Theme Music: Secrets Explained

The theme music for the original Star Trek series is a fantastic masterpiece, reflecting the amazing imagination of its creator, Gene Roddenberry.

Composed by Alexander Courage in 1966, the theme is fifty seconds long and it incorporates a blend of classical orchestration and futuristic sounds.

Brilliantly composed by Courage in only three days, the end result was a beautiful piece that embodies hope and adventure.

Roddenberry played a vital role in shaping the theme and, interestingly, he wrote lyrics for it, although they were never used.

The music not only became synonymous with the series, but also seeped into popular culture, finding its way into countless parodies and media forms.

The composition ingeniously includes the unusual tones of the theremin, an electronic musical device played without human physical contact. A theremin produces sound based on the proximity of the player's hands to its antennas, creating eerie and haunting tones. This innovative inclusion added an element of the unknown, and also perfectly captured the show's futuristic and otherworldly themes.

The haunting celestial vocalizations in the theme were actually sung by a choir, and not made electronically. They create a mysterious quality synonymous with the uncharted territories that the Enterprise explored.

The original Star Trek series theme is a testament to the creative ingenuity of its composer and the visionary spirit of its creator. Its enduring appeal lies in its ability to evoke a sense of mystique and excitement, inviting us on a journey through the universe of imagination.

Subscribe for photos and articles

🖖😍 Star Trek Gigi

Recent Posts

The Sexy Influence of Star Trek Short Dresses

Star Trek Behind the Scenes: Who does the Laundry?

Star Trek's Subspace Radio: Is it Really Possible?

You know the reason Gene wrote lyrics to the original theme is because he wanted a cut of the royalties instead of the composer? He was a lot of things, greedy amongst them.

Composer Jeff Russo Boldly Takes ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Into New Musical Territory

By Jon Burlingame

Jon Burlingame

- Dan Wallin, Oscar-Nominated and Emmy-Winning Music Mixer, Dies at 97 3 weeks ago

- Walk of Fame Honoree Lang Lang Seeks to Inspire Kids by Linking Classical Music and Disney Songs 3 weeks ago

- ‘Law & Order’ Composer Mike Post Creates New Bluegrass and Blues Album (EXCLUSIVE) 1 month ago

Composer Jeff Russo felt the weight of more than half a century of music for the various incarnations of Gene Roddenberry’s sci-fi epic when he sat down to write the theme for the new “Star Trek: Discovery,” debuting Sept. 24 on CBS (and continuing on its CBS All Access streaming service).

The concept came from his initial discussions with producers. “We talked about the idea of ‘Star Trek,’ which is exploration and harmony and discord between people and species,” he says. “Yes, people fight, but the overall theme is that we’re all one. What could I do to embody that in music?”

He remembered the idea of “common tone” in music theory: “If every chord I played shared one single note, how could I fashion that and then write a melody on top of it? The idea of a commonality in people and species — I wanted to apply it to the music.”

Then, to tip his hat to Alexander Courage’s original “Star Trek” theme, he bookended his new music with elements from that famous fanfare. The 100-second theme — long for network — combines an air of mystery, a propulsive rhythm and a hopeful feeling while reminding viewers that it’s all still “Star Trek.”

Popular on Variety

Russo, a three-time Emmy nominee and recent winner for his music for FX’s “Fargo,” watched the original series in reruns as a kid in 1970s and became a self-described fanboy of “Star Trek: The Next Generation” in the 1980s. A former rock drummer and guitarist, his other recent series include “ Legion ” and “The Night Of.”

Like all previous “Trek” series, “Discovery” is scored orchestrally. “We said, ‘We’re not doing this on a synthesizer,’” says exec producer Alex Kurtzman . “Jeff has a modern sound that’s also rooted in the classical film composers. We wanted to make ‘Discovery’ a movie on television.”

Russo used a 64-piece orchestra for the pilot and 51 players for each of the six episodes scored to date.

“Discovery” is the first of the six “Trek” TV series to have a single composer writing every score. With each episode averaging from 31 to 38 minutes of music, it takes Russo six days to finish a score. He can work quickly because he spent weeks developing a series of secondary themes — for Michael Burnham (played by Sonequa Martin-Green), Starfleet, Klingons and others — that are useful as the 15-episode story arc unfolds.

Unlike earlier musical treatments of the warlike Klingons, “it’s not all gloom and doom and marching drums,” Russo says. Instead, he’s manipulated guttural vocal noises and added ethnic wind instruments for a unique sonic signature for the race.

Russo had a loftier goal: “Connect the audience to these people who have their own emotions, their own thoughts and feelings. They’re fighting for their own place in the universe. There is an emotional aspect to some of the music I’ve written for the Klingons. We don’t need to play bad-guy music.”

More From Our Brands

Mandisa honored with special ‘american idol’ tribute performance, former google ceo eric schmidt is selling his silicon valley estate for $24.5 million, reynolds, mcelhenney bring wrexham playbook to club necaxa, be tough on dirt but gentle on your body with the best soaps for sensitive skin, the voice: did the right 6 contestants make it through to the lives, verify it's you, please log in.

An archive of Star Trek News

Trek Composers: Twenty-Six Seasons Of Star Trek Music

- Cast & Crew

During the fifty plus years of scoring music for various Star Trek shows, four composers are primarily responsible for the different show themes and music.

The composers include Ron Jones, Dennis McCarthy, Jay Chattaway , and Jeff Russo .

The composers had a tricky assignment, enticing original series fans. Jones addressed this by adding something familiar at the beginning of the TNG theme. “What I was told by Robert Justman is that Paramount was worried that everyone who was used to the original Star Trek was used to Shatner and Spock and the look and the feel of that show,” he said. “And now here’s this new one with a British captain with a bald head, and there’s a Klingon there — it was a weird cast! It was like a nightclub in Denmark. It was a weird group of people. And Paramount was worried about that. That’s why they used Jerry Goldsmith ‘s familiar theme at the beginning.”

“I never questioned it,” said McCarthy. “They wanted Jerry, so if that’s what they want, that’s what they’ll get. I did write a theme — I called it the Picard Theme — because I thought they might want one. I had done Dynasty and other shows that were heavily motif-driven, so I thought it might be nice to have a motif for Patrick Stewart . So I wrote this theme that’s floating around on a CD somewhere, and I used it and they liked it. And then about three shows later, I used it again. But they stopped and said, ‘Wait a minute. We’ve already heard that. Don’t do that again.'”

Deep Space Nine was “challenging because it was claustrophobic,” said Chattaway, “but in some ways that made it more interesting. And I think viewers now are coming back to that show and saying, ‘Wait a minute. This is pretty amazing.’ I found it more interesting because it wasn’t about going out to blow up some planet. We had to develop some personal connections and write more personal music. Like the quirky Quark music. It was fun. It wasn’t your typical genre of what space was all about. It was fun. It wasn’t your typical genre of what space was all about.”

Working on Voyager was “like backing into the Next Generation again,” said McCarthy. “It was closer in attitude to The Next Generation and the original series than Deep Space Nine . By that time, we were given permission to be a little bolder. It was a good experience.

McCarthy wrote the music for the first and the last episodes of The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine , and Enterprise . “It’s very satisfying,” he said. “There’s sadness, of course, because you hate to see the series end. And with Enterprise , it was really sad because we were hoping to go longer. That was also the last I’d see of that giant orchestra. I’d have fifty to sixty people per episode. It was a wonderful, wonderful experience.”

Star Trek music is “an adventure,” said Russo. “You never know where it’s going to take you. The thing that I’ve enjoyed injecting into Star Trek music is trying to also find an emotionality to it. Telling the story from a character perspective and be able to connect those things thematically.”

About The Author

T'Bonz

See author's posts

More Stories

Cruz Supports Rapp’s SAG-AFTRA Candidacy

- Star Trek: Discovery

Jones: Creating Your Own Family

Burton Hosts Jeopardy! This Week

You may have missed.

Several S&S Trek Books On Sale For $1 This Month

- Star Trek: Lower Decks

Another Classic Trek Actor On Lower Decks This Week

Classic Trek Games Now On GOG

- Star Trek: Prodigy

Star Trek: Prodigy Opening Credits Released

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Alexander Courage, ‘Star Trek’ Composer, Dies at 88

By Margalit Fox

- May 31, 2008

Alexander Courage, an Emmy-winning Hollywood composer whose most famous work was the strange, soaring and instantly recognizable theme from “Star Trek,” died on May 15 in Pacific Palisades, Calif. He was 88 and until recently lived in Malibu.

His stepdaughter Renata Pompelli confirmed the death.

Familiarly known as Sandy, Mr. Courage wrote music for hundreds of television shows and films. But he was forever identified with the sweeping, ecstatically overwrought strains that opened “Star Trek,” first broadcast on NBC from 1966 to 1969.

The theme took on a life of its own. It was heard in all the “Star Trek” movies and several of the later television series. It cropped up on an episode of “The Simpsons” and in the films “Wayne’s World” and “Muppets From Space.” It was recorded by jazz musicians like Maynard Ferguson and by symphony orchestras.

The son of a Scottish father and a French-American mother, Alexander Mair Courage was born in Philadelphia on Dec. 10, 1919. In 1941 he earned a bachelor’s degree from the Eastman School of Music, where he studied composition, music theory and French horn. He also studied conducting with Serge Koussevitzky at Tanglewood. In World War II Mr. Courage served as a bandleader with the Army Air Corps.

After the war Mr. Courage joined CBS Radio, composing and conducting for shows like Hedda Hopper’s “This Is Hollywood” and “The Adventures of Sam Spade, Detective.” From 1948 to 1960, he was an orchestrator and arranger at MGM, where he worked on a string of well-known musicals, among them “The Band Wagon,” and “Gigi.” He also orchestrated and arranged music on the films “Guys and Dolls” and “Funny Face.”

In 1965 the writer and producer Gene Roddenberry asked Mr. Courage to create the theme music for a television pilot about a starship and its crew. According to published accounts, Mr. Roddenberry, wanting to avoid what he called “space music” anything too avant-garde told Mr. Courage not to use electronics.

Mr. Courage’s score opens with a bold fanfare for brass, followed by a lyrical theme for French horn. Over the music are the wordless strains of a high soprano and a whooshing sound (vocalized by Mr. Courage), which accompanies the starship Enterprise as it passes across the screen. The net effect is an exquisite combination of pomp and cheesiness, Valhalla and Vegas in equal measure.

Mr. Courage composed the background music for just four additional episodes of “Star Trek.” But he wrote music for hundreds of episodes of other shows, including “The Waltons,” “Eight Is Enough” and “Lost in Space.” He composed one other television theme, for “Judd for the Defense,” broadcast on ABC in the late 1960s.

With three colleagues, Mr. Courage won an Emmy for Outstanding Achievement in Music Direction for the 1987 ABC special “Julie Andrews: The Sound of Christmas.”

Mr. Courage’s first two marriages ended in divorce. His third wife, Shirley Pumpelly Courage, whom he married in 1980, died in 2005. Besides his stepdaughter Renata Pompelli, he is survived by three other stepchildren, Raphael Pumpelly, Andrea Steyn and Lisa Pompelli, all of Los Angeles; and six grandchildren.

An obituary on Saturday about the film and television composer Alexander Courage, who wrote the “Star Trek” theme, misidentified the studios that produced two of the movies for which he orchestrated and arranged music. “Guys and Dolls” was a Samuel Goldwyn production distributed by MGM; it was not an MGM production. “Funny Face” was made by Paramount, not MGM.

How we handle corrections

- Entertainment

- Sports Sports Betting Podcasts Better Planet Vault Mightier Autos Newsletters Unconventional Vantage Experts Voices

- Subscribe for $1

- Sports Betting

- Better Planet

- Newsletters

- Unconventional

Every 'Star Trek' Theme Song Ranked

It's hard not to take the Star Trek: Enterprise theme as an affront upon first hearing it. There's nothing science fiction feeling about it, and none of the orchestral swell found in previous Star Trek series themes, which foreshadowed the more perfect human future ahead. Instead, it's a twangy soft rock ballad version of a song from Patch Adams , which had come out less than three years before Enterprise . But this time "Where My Heart Will Take Me" was sung by British opera tenor Russell Watson instead of Rod Stewart.

- 'Picard' Is the First 'Star Trek' Launched By a Woman Director

The discordance was clearly no accident. Enterprise was meant to stand apart from other Star Trek s in any number of ways—the words " Star Trek " didn't even appear in the title until the third season. But there was an instant backlash to the saccharine theme when Enterprise premiered in 2001, with fan protests and petitions calling for a return of "score that is without vocals, as traditionally used by Star Trek television series."

"What's a Star Trek series without something for people to hate?" Star Trek series producer and Enterprise executive producer Rick Berman said at time, responding to the backlash for SciFi Wire.

But for all the sputtering, it's hard not to find a Star Trek theme with singalong lyrics at least a little charming, even if its syrupy sentiment would make actually singing along embarrassing. The Enterprise theme may have sucked all the mockery in the galaxy into its orbit, but it's a little hard not to admire them for sticking by it, even doubling down with a baffling third season pivot to a new version—this one smooth jazz-pop, which sounded a little as if the record player had been sped up slightly to get it over with.

While few would dispute that "Where My Heart Will Take Me" is the worst Star Trek theme , it has still, for the most part, been tolerated, sometimes even embraced. NASA archivist Colin Fries confirms Space Shuttle crews were subjected to it four times, with "Where My Heart Will Take Me" serving as a wake up call twice as often as the themes for the original Star Trek or The Next Generation . (Other selections used for morning esprit de corps on space missions included the theme from the 1965 Western For a Few Dollars More , "Eye in the Sky" by Alan Parsons Project and "Gettin' Jiggy Wit It" by Will Smith.)

Watson, the song's singer, probably described the journey towards acceptance best: "Something new happens, and people aren't quite sure of it. But they'll get used to it," he said in 2001 . "By the time they've watched the 20th episode, they'll be thinking, 'Well, it's not that bad after all.'"

He's probably right. Those sticky lyrics ensure you'll never forget it.

Cause I've got faith, of the heart.

I'm going where my heart will take me.

I've got faith to believe.

I can do anythinggggggg.

But while it's easy to step on the Enterprise song, ranking the rest of the Star Trek themes—which stick closer to the style of the soaring orchestral introduction that first appeared before the very first episode, "The Man Trap," on September 6, 1966—is a lot trickier. A 2013 poll by the official Star Trek site found a split fanbase, though the most substantial support went to the same two themes as top this ranked list.

Star Trek: Discovery

Jeff Russo's Star Trek: Discovery theme is cluttered with instrumentation. This sometimes works beautifully, including its early, mournful horn build-up and the confident strings vibrating after, but the cumulative effect is a little too mathematically fussy, made worse by an emphasis on propulsive energy over mood. But the Discovery theme might have been able to stand on its own if it weren't for the decision to sink it between two nostalgic stings from Alexander Courage's original Star Trek fanfare.

Star Trek: The Animated Series

With story editor D.C. Fontana's focus on tight science fiction plots and most of the original cast returning to voice their characters, The Animated Series felt like another year in the Enterprise's five-year mission—rather than just Star Trek for kids—when it debuted in 1973, four years after the original series' cancellation. But while Star Trek: TAS did everything right, there was no disguising the limited animation or the derivative theme, composed in-house by the animation studio's cofounder and their prolific cartoon composer, both bearing pseudonyms.

But while it's missing the orchestral grandeur of other Star Trek themes, The Animated Series music is undeniably jaunty. It's chintzy for sure, but there's a colorful bounciness to it that gives it an enduring camp appeal.

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

Created by longtime Star Trek series composer Dennis McCarthy, who scored hundreds of hours—from the first episode of The Next Generation to the last episode of Enterprise —the Deep Space Nine theme has an unimpeachable pedigree. Opening with a lonely trumpet solo, it's a moody introduction to the remote space station setting for the series.

But from there, the DS9 theme expands into a repetitive martial fanfare. Loaded with trumpets and French horns, it's a song that feels like it's perpetually revealing, instead of going anywhere. While its theme is in line with the diplomacy and war of the series (and a fourth season re-orchestration adds a little more energy), it's a little too stately for a series that deconstructed the high-minded planet-hopping of The Next Generation , pioneered Star Trek serial storytelling and pushed the United Federation of Planet's utopian principles to their breaking point.

Star Trek: Picard

Where Deep Space Nine is a one-dimensional theme that doesn't suit its fascinating show, Star Trek: Picard is everything its series is not. Composed by Russo, but far less slavish than the nostalgic Discovery theme, the main title for Picard feels mysterious and hopeful, combining strings to evoke the cultured, urbane Jean-Luc Picard with a pining flute—a reminder of the starship captain's soulful playing of his Ressikan flute (an instrument he learned to play in the beloved TNG episode "Inner Light"). While the series devolves into a busywork action adventure, the theme song has an earthy sentiment, perfect for a Star Trek series about a planetbound captain returning to the stars.

Star Trek: The Original Series

"I don't want any of this goddamn funny-sounding space science fiction music, I want adventure music," composer Alexander Courage recalls Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry telling him, in interviews excerpted in the 2013 collection Music In Science Fiction Television: Tuned to the Future . "He wanted something that had some balls and drive to it."

Courage combined woodwinds, a harp, a vibraphone, French horns and Loulie Jean Norman: a soprano singer from The Dean Martin Show , who was the first to sing the wordless Star Trek melody. The result is a theme that is both adventure-driven (you can almost hear trotting horse hooves underneath the singing) and iconically sci-fi, as the first four notes ring out like satellite pings over the depths of space.

Courage even created the "woosh" sound effect as the Enterprise zips across the screen during the opening credits, by making the sound with his mouth. (Gene Rodenberry would later write useless, never-sung lyrics so he could lay claim to half of Courage's royalties).

A beautiful version of the theme also popped up in Star Trek: Discovery , right after the reveal of a rendezvous with the U.S.S. Enterprise at the end of the first season finale. Discovery and Picard composer Jeff Russo assembled a 74-piece orchestra, more than doubling the original recording.

Star Trek: The Next Generation

Jerry Goldsmith was nominated for Best Original Score at the 1979 Academy Awards for the 12th time for his soundtrack to Star Trek: The Motion Picture . Unlike his second nominated score—the experimental, influential and deeply strange music for Planet of the Apes— Goldsmith's Star Trek movie score was bold and unabashedly accessible. Goldsmith cited the direct influence of John Williams' theme for Star Wars , which came out in theaters two years earlier—not the last time the series would aim for the more mainstream appeal of the space opera pulp adventure.

The opening fanfare became so central to the Star Trek identity that McCarthy, the composer who would go on to create the DS9 main theme, rearranged The Motion Picture theme for the opening of Star Trek: The Next Generation nearly a decade later.

The result is likely the most iconic Star Trek title track. Booming and heroic, it evokes the more elevated and diplomatic dilemmas confronted by the starship Enterprise of the 24th century, redefining the series from James T. Kirk's swashbuckling adventures a century earlier.

Star Trek: Voyager

The Next Generation theme may be the defining musical motif for all of modern Star Trek , but Goldsmith topped its sonic pleasures when he composed the Voyager theme in the middle of a decade-long run scoring Star Trek movies (including beloved entries like First Contact , and loathed ones like Nemesis ). Completely different from the marching rhythm of the TNG and DS9 themes, Voyager recaptures some of the spacey ethereality of Courage's original vocal melody, while adding a deep space resonance that evoked the series' lost explorers, far from home among uncharted stars.

Unlike most other Star Trek themes, there's not a hint or sample of what came before in Voyager 's main title, emphasizing how apart the series was from the supportive unity of the United Federation of Planets. Rather than the drumbeat of purpose, Voyager captures a more open-ended sense of searching. Of the Star Trek series released since The Next Generation , it's the Voyager theme that sounds the least martial and most exploratory. This is music to calibrate your nacelles to.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.

- Newsweek magazine delivered to your door

- Newsweek Voices: Diverse audio opinions

- Enjoy ad-free browsing on Newsweek.com

- Comment on articles

- Newsweek app updates on-the-go

Top stories

Texas Map Reveals Areas With Most High School Dropouts

Japan Map Shows Where it Intercepted Chinese and Russian Warships

University of Florida Comes Down Hard On Protesters: 'Not A Daycare'

Kari Lake Speaks Out About Donald Trump 'Rift'

- April 29, 2024 | Preview ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Episode 506 With New Images. Trailer And Clip From “Whistlespeak”

- April 28, 2024 | Interview: ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Writer Carlos Cisco On Unmasking The Breen And Revisiting The ISS Enterprise

- April 26, 2024 | Michael Dorn Wanted Armin Shimerman To Play The Ferengi That Worf Killed In Star Trek Picard

- April 26, 2024 | Podcast: All Access Gets To Know The Breen In ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ 505, “Mirrors”

- April 25, 2024 | Prep Begins For ‘Star Trek: Strange New Worlds’ Season 3 Finale; Cast And Directors Share BTS Images

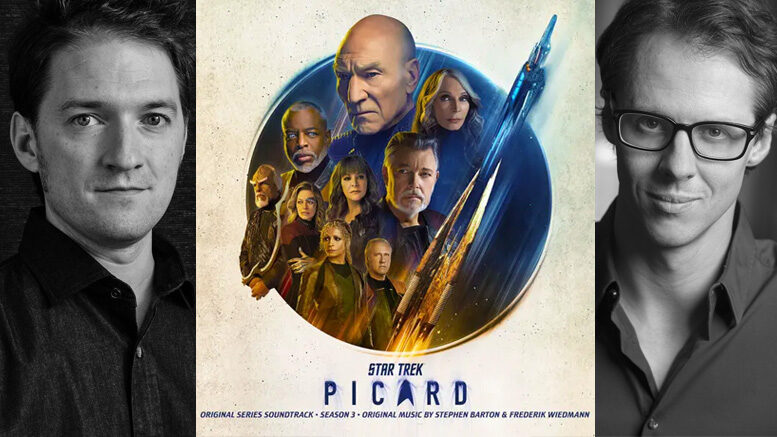

Interview: ‘Picard’ Season 3 Composers On How They Are Reviving Classic Star Trek Music

| March 29, 2023 | By: Jeff Bond 50 comments so far

Paramount+’s recent Star Trek series Discovery and Picard have employed composer Jeff Russo to bring a modern edge to the shows while occasionally tipping a hat toward the thematic material of earlier Trek composers. But for Picard’s third season, showrunner Terry Matalas recruited British composer Stephen Barton, who worked with Matalas on SyFy’s 12 Monkeys , and Frederik Wiedmann (who’s scored everything from numerous DC animated movies to children’s TV shows and video games). The pair were given a specific mission: resurrect the bold, in-your-face orchestral style of the classic Star Trek movies, with major callouts to themes by Jerry Goldsmith, James Horner, Cliff Eidelmann, and even Leonard Rosenman. The result is some of the most exciting Star Trek scoring in years, music that has fans fired up for the imminent soundtrack release. TrekMovie sat down with the composers for an extensive discussion to talk about this classic musical approach and how they tackled it.

Who do you guys answer to on Picard in terms of scoring? And what was the brief, just in general, when you started?

Stephen Barton: Terry Matalas and I had talked about Trek for a long time, actually, particularly when 12 Monkeys was going on. He’s a veteran of Star Trek —he was a PA on Voyager and then worked as a writer on Enterprise . So he’s kind of come up through the ranks on the Star Trek side. And when I first started working with him, five, six years ago, it was something we chatted about quite early on. I think even when I first met him for lunch on the Paramount lot it was one of the things we chatted about. And add the fact we had a shared past in that sense, in terms of what Trek we had grown up with, which was for both of us a case of parents having seen the original series, but the first time we got a series of our own was really Next Generation and watching it as kids. He’s a little bit older, but I was watching it when I was like five or six. I think for both of us it was very much a defining point in our relationship with television and with media in general. Akiva Goldsman was still very much running Picard season two and Terry was very much involved at the beginning of the season as a writer but about three or four episodes in he split off to really look after season three, which was always going to be his baby.

Terry very much pitched it to us as this idea of, let’s look back to the whole of the franchise and let’s look back, really in-depth at the Horner and the Goldsmith scores. Let’s look back at Dennis McCarthy’s work. Let’s look back at Ron Jones’ work, Cliff Eidelman, and Leonard Rosenman, looking back at all of it, let’s take a step back and look at what it means. And because the other thing was, obviously with Trek there’s been so many iterations and things used from one version into another, sometimes without a sense necessarily of what specifically something means. Even the Alexander Courage theme, this is a general Trek theme now and even was, I think, by the third movie, with the idea that this isn’t a specific thing; this is a wider theme. So, I think that was always what we were talking about.

And then as we got through the season, we were about six episodes in and one of the things we set out to do at the very outset was score it all. We weren’t going to do the typical TV thing of tracking, but the problem is, the shortest episode is 50-something minutes. So it’s 500 and something minutes of television. To most TV shows it would just be, we’re going to track half of this, or track a third of this or have three episodes in the middle which are just edited with some interstitials and things like that. And he was like, “No, no, I want to treat every scene of this like one of the scenes in the feature films.” And so, there are two ways to do that. Either you write a ton of music or… well, that’s basically the only way of doing it, really. So that was kind of the genesis of it. And we got about episode six, and I think I’d been on it for three months, I’d written about five hours of music, and was just dead, and we got to this point where we’re like, do we sacrifice the vision? Do we sacrifice that? Or do we get some help? And mercifully, episode seven to nine had a ton of Freddie’s music in the temp track. Because I think that’s one of the things that Drew Nichols, our editor, tried to do-he tried to temp with not Star Trek music, just to be able to get a lens on it, that was different to just putting Trek music wall to wall, which is obviously incredibly easy to do, because there’s so much of it. So Freddie came in and saved the day and took two episodes over and knocked them out of the park, and actually really allowed me to do what I want to do, which is to land the last 30 minutes of the final episode.

Frederik Wiedmann: I was just looking at the minutes for the final episode and I’m counting 55 minutes of music. In one episode of TV.

Frederik Wiedmann, Drew Nichols, Terry Matalas, and Stephen Barton (center four L-R) during Picard scoring session at WB Eastwood scoring stage

Since you mentioned Ron Jones, did you discuss the whole Rick Berman aesthetic versus what Matalas wanted? Because even though the scoring is different for the first two seasons of Picard , there’s a lot of active music, but this in particular, it’s very upfront in the mix and hits things. It is more of a movie aesthetic or a Ron Jones Next Generation aesthetic, as opposed to what the TNG music turned into by season four or five.

Barton: Yes, we discussed this at length. It wasn’t necessarily always even with the Ron Jones stuff what the music was doing in terms of harmonically or thematically, it was just in the way it’s paced and the way it’s scored. And I went back and watched what for me is the pinnacle of season three of Next Generation —at the end of “Best of Both Worlds, Part One,” the end of season three, which for me was ingrained in my mind in the summer of 1990. You have music that’s very overtly scored, it goes right for the jugular, it’s not holding back at all, but it works and it’s not full of music that you separate from the picture, it just is part of it. And so, scoring like that, that it’s okay to be big and it’s okay to go off to moments. And funny enough, I think in episode three, we had a big homage—there’s a big sequence with the first time Vatic fires the weapon, that’s very much an homage to Ron Jones throughout that whole sequence. It just goes there and it says, let’s turn the burner up to 10 and go maximum in terms of the way it’s scored. It’s okay to be big and it’s okay to make bold statements and okay to play melody. And I think that was very much the focus, because that’s what we loved from the Trek both Terry and I remember; that’s kind of a hallmark of it. And Freddy has a number of massive moments in episode seven that are very, very similar, that were just moments where you play it.

Wiedmann: It’s funny, when I watch old movies, including all Star Trek , I’m always baffled by how little music there is actually, in an episode or a movie, how much space there was back then, that was okay. Even when you watch a James Bond movie from the Sean Connery-era Bond, there is so little score in the entire movie. And when it comes, it’s big. It’s bold, and it has a very distinct purpose. I think the aesthetics have changed a lot over the past 20 years in terms of scoring movies, especially in the sci-fi genre, where there’s a lot more music now, and a lot more subtle stuff in between. What used to be just empty space and ambiance now has something like a little pulse or something going on to keep the tension going, that we just didn’t do back then. And I think one of the big challenges in this particular Trek was how do we make it feel like the old ideas, and the old sonic templates for Star Trek while taking it into this current time of scoring? And I think that the response so far has been fans have absolutely noticed how much we go back to the roots of Star Trek sounds while also kind of giving it this modern edge I think it needed.

You have, I think, at least five or six themes that are preexisting, very specific melodies. And then you provide one major new one, I know that there are other pieces of new material, too, that you guys develop, but you have a theme for the Titan that is in the end title. So first, tell me a little bit about developing that. I was talking to someone who’d seen the early episodes before I had and he said, “They’re playing James Horner music.” And when I heard this theme, I realized the theme is not James Horner’s, but the setting it’s in is very evocative of Horner.

Barton: Yeah, that was 1,000% the goal with that. I think the thing that Horner brought to Trek , which I think some people would say is not in the Goldsmith scores—but I think it is, it’s just a lot more buried—is that kind of nautical thing, the militaristic feeling, but it is a very specific, militaristic thing of very much feeling that these ships are just boats in space. Everything from the very classical horn kind of harmonic series, like we’ve got two horns in pairs going up and down the harmonic series, those sorts of motifs, they have a very English feel, and that was something that Horner was very interested in. He was obviously an anglophile and I had the pleasure of meeting him once, actually, only at Abbey Road one time, but I think that that part of Trek was something we felt had been put aside a little bit. It wasn’t that we wanted to necessarily turn it back to being Wrath of Khan but it’s just acknowledging the fact that whilst this is a ship of exploration, it’s still a military command structure, there’s still danger, and I think that the Horner scores for me (danger being one of his motifs, literally , but we then do use his danger motif), it was one where we talked at length about it as, “This is the strongest of spices,” in terms of its musical presence, and I think that’s why James Horner liked it. It’s just such a bold statement, that to not use it to us was almost disrespectful. We’re not going to plaster it everywhere, but I think when we’re in the nebula, there is obviously a bit of a callback to the Mutara Nebula cues.

And so the Titan theme, I think I looked back through a lot of the orchestration, and had access to a fair number of the written scores and I was really looking about how it was constructed. And what was really interesting about Horner’s scores is how he works with limited resources. You get a sense of a very full sound playing, but it isn’t tutti, it’s not wall-to-wall, whereas the Goldsmith scores tend to be very dense, there tends to be a lot going on. And virtually everybody is doing something—during the main title, I don’t think anyone has any bars’ rest in the whole piece, they’re all doing something, whereas the Horner scores are often quite stripped back, very pointillistic, and very focused in their orchestration. There might be quite complicated things, so you have these violin arpeggio figures and I was having to sort of consult on whether they were even playable, because some of them were trying to do some augmented chord stuff that was a little tricky under the fingers. So I think that was the overriding thing with the Titan theme; it was very much an homage to James Horner versus the rest of Trek stuff, the Jerry Goldsmith stuff.

Here is the brilliant @ComposerBarton conducting his Titan theme with all those wonderful nods to Horner in his arrangement. String section only. It’s been stuck in my head for over a year. #StarTrekPicard pic.twitter.com/f5YCKXI6MS — Terry Matalas (@TerryMatalas) March 4, 2023

So did you sit down and discuss or map how you were going to employ all these themes? Because you’ve got Goldsmith’s March theme, which became the Next Generation theme; you have his First Contact theme, and you have that motif that’s actually from Star Trek V [the “Busy Man” motif from the cue of the same name], and the Klingon theme—and it’s obvious how you’re going to use the Klingon theme, but the other themes, you’re using them but not necessarily the way they were used by Goldsmith. So how did you decide where you were going to apply these themes?

Wiedmann: For my episodes, in particular, it was really all Terry’s roadmap. He’s got an incredible knowledge of Star Trek music, going back to the beginning of it, more than anybody I’ve ever met. And Terry gave us this specific and detailed kind of map, with, “This theme here, I want this thing here.” And he and the editor Drew, they kind of created this roadmap for us where things needed to be dealt with, small adjustments based on our creative ideas that the music had to adjust to, as we were writing. But in general, I would give Terry all the credit for placing the moments and the thematic ideas from the old Trek into the right pivotal places.

Barton: The “Busy Man” motif [from Star Trek V: The Final Frontier ] came to represent a lot of the stuff to do with both Commander Data and then also it’s almost like a nostalgia theme. It’s used in a few places where it’s not specific to that, but it’s used in a couple of places where it’s used to introduce the First Contact theme. And that’s been something where, lots of people say, “Oh, it’s the First Contact theme, it represents first contact. And to me, actually, when you look at the way Goldsmith uses it, the most poignant usage of it for me is in the scene where [Lily, the Alfre Woodard character], is seeing Earth from space for the first time. When she points a phaser at Picard and he gets her to put it down, and he says, “Okay, you’re really on a spaceship.” So for me, that theme always represented the love of spaceflight, and for me what I think Goldsmith was so good at doing was finding themes that can play from different perspectives. So, in those sequences, it’s playing both from the perspective of the audience looking through the crew’s eyes, like you’re going back to this great historical event, but also then you’re looking at the perspective of Zefram Cochrane and you’re looking at all these people with the goal of spaceflight ahead of them.

So, for me, that was always the “nostalgia for spaceflight itself” theme. And so that’s a lot of why we use that in the end credits. And also partly because it was one of those ones where we just felt that theme deserves to be heard more. We put it on the end credits because we felt that it just said something in a really nice way; that it said a lot more about what we were trying to say about the season to the audience. Then the Titan theme, I think very much was looking towards the same thing, where the original Jerry Goldsmith march became very much the Enterprise theme and very much represented the ship and its crew, and we knew we needed a theme for the Titan to do the same thing. This is the Titan and its crew, and obviously, there are places we then take that we haven’t shown yet, so very much that has a purpose and that is going somewhere.

Frederik Weidmann during a Picard scoring session

I think there’s some variation, at least one variation early on of the First Contact theme, something where it’s presented in a way that hasn’t been done before. So obviously, you’ve got access to the written scores for all this material, but have you internalized any of it enough so that you can just go ahead and write that? Or do you always need to refer to the written scores?

Barton: Really good question. Some I have internalized, because some of the genesis of that music and some of the influences on that music, I would certainly count as influences my own, particularly in some of the lesser-known influences, some of the English composers particularly. Growing up with a lot of English choral music and things like the Walton Henry V score, that’s not a million miles away at times from some of the stuff Horner was doing in terms of some of the ways it’s built, and particularly the horn writing. I think that’s one of the hallmarks, but it draws from other influences, too. But there’s a very Waltonian thing in there. And it’s funny with the Shakespeare reference, which plays a lot into certain parts of Trek , and I don’t think that’s an accident in the sense of how it’s scored. So I think that stuff comes a lot more naturally. I find the Goldsmith stuff harder to work with in terms of how it’s built, largely because it’s so heavyweight. He built the big sound before anyone else does. When we sometimes think of combos in the ‘90s and 2000s, of doing the big wall of noise and synths and stuff like that, he was doing it well before then. It’s very much that use of the whole spectrum, and the difficult part of that is time. Building those really dense scores takes a while. I can’t really rush it. And we just didn’t have very much time.

Wiedmann: I can tell you that there’s a short synth-only theme from Goldsmith that we’re using in the later episode for a very particular character. And it took me ages to make that sound out of my synthesizer. There’s probably just a patch Jerry had on some old keyboard, but I had to create it to make it feel just like that, and it took me way longer than dissecting an actual orchestral score. It’s a theme played with a very specific synth sound that fans will be able to tell exactly who I’m talking about when they hear it, so I really can’t talk about it because that hasn’t aired yet.

There’s a specific sound in movies you hear a lot for the past decade. Supposedly, Hans Zimmer invented it, but I’m not necessarily sure that he did. It’s this thing we just call the “ Braaam .” It’s this big bass noise that’s in Inception . But I was thinking actually, that this almost goes back to the blaster beam Goldsmith used for V’ger in Star Trek: The Motion Picture . That was actually the first time that kind of approach was used, and so it’s unique and specific to that. And I was thinking, “Oh, this is almost like blaster beam sound,” in some of the Shrike scenes.

Barton: Yes. Very much. I think we had exactly that conversation in February. It’s interesting where things like that become ubiquitous, and particularly in trailers. You could look at it two ways: on one side you could say, “Well, it’s a lazy trope of action writing.” But then you could also look at it as at its core it’s fundamental—you can go back to Carl Orff, Carmina Burana , if you play the orchestral version, not necessarily the two-piano version, it basically starts with that figure, and it’s one of those strong spices. I think the problem is that sometimes the tendency is to just chuck it in like a handful of chili peppers that blows your head off in two seconds. Fabulous, but then 10 minutes later, you’re like, it’s not a particularly good experience, and you’re regretting it. Gordie Howe and I talked about this a great deal on Star Wars as well, on the stuff we’ve been doing together, because if you just plaster the “Force Theme” everywhere, it loses any impact it will ever have. And it’s one of the most precious gems you can be entrusted with. So, I think even when Freddy and I were working out where we have these themes, literally sitting down and asking yourself, how should this be harmonized? Or how should this be accompanied and what’s the arrangement and making it not just a, “press button, Trek theme here,” but actually something that weaves in and out and feels cohesive with the narrative. We did a wonderful session with Craig Huxley, who plays the blaster beam, and we brought him in on the first episode to do some of the sound design around the Shrike.

Blaster Beam on the mixing board from Picard scoring session

Tell me about some of the other new material that you guys produced. And in terms of what you can talk about, there’s a number of dialogue scenes between people where you guys come in very quietly, and I was feeling like I was starting to hear melody, maybe for Roe and Picard. There’s something that plays I think when they’re having their final goodbye. And then you also hear it when Riker and Picard are looking at her Bajoran earpiece, her spycraft. And there’s a big birthing scene in the nebula that has this specific music for it. So how much specific character-centered material did you come up with?

Barton: That’s the family theme, which is what we eventually christened it. We went through many names, it didn’t really quite have a name at first. It’s something that is in the nebula birth sequence, but is hinted at throughout episodes earlier; you kind of hear hints at it. There’s a very, very oblique reference to it the very first time Beverly and Picard catch eye, that very slow string arrangement, but it’s very buried in there. And gradually we unfurled it, and it’s actually very much based off the Star Trek V “Busy Man” motif, but it’s upside down. So the flow takes the first three notes of that and then expands out and that was very much deliberate, and there are reasons for that, actually, that we can’t talk about yet. But there’s a very good reason for that. So the family theme, I think, was the big one, that we unfurl and kind of show for the first time in its full bent. And the other thing that Terry was very adamant about was that he wanted a theme that had a beginning and middle and an end that you play the whole way through. And then, funnily enough, we played it again in Episode Six, pretty much end to end as well.

Did you rerecord the end title, the arrangement of the First Contact theme and the march?

Barton: Those two aren’t rerecordings, those two are actually the original recordings. We went back and found the original—I forget what the mixes of them were off the top of my head, whether they were just LCRs or whether they were 5.1, I think I think First Contact was 5.1. And so they’re cleaned up to a degree so it is a bit of almost a remaster, but those two pieces, we didn’t rerecord. But that was largely because of time, because the other thing we inherited was very much a schedule from two seasons of previous TV, and to a degree of budgets as well. So we had one session in LA where we recorded, I think, 41 minutes in three hours—the musicians were just amazing; we could not have done this anywhere else. The L.A. musicians just killed it, but so many of them have played on so many of the scores. I think when [music contractor] Peter Rotter put the call out, we very much said what it is and we went out after people who had played on [the previous Trek movie scores] and said, “This is what we’re trying to do. We’d love you to come play.” So we had some players who I hadn’t seen in a number of years at the session, and we were actually very honored to have Steve Erdody, who’s playing cello. It was I think his last session pretty much not If not his last batch of sessions, but maybe his penultimate; I think Indy V might have been his last.

There are some pretty deep cuts and other things you referenced. For Daystrom Station you are referencing the orbital office complex music from Star Trek – The Motion Picture . And then there’s the whole museum scene where you even referenced Leonard Rosenman’s Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home theme, which I was really impressed by.

Barton: Leonard Rosenman and sneakily, there is the Horner Klingon theme on the top! That cue, I literally kind of sat down and said, “How many references can we get in?” Some of them are all completely obvious. But even there, we looked at how the harmony, for example, of the Voyager theme—because I find that to be one of the most restrained Goldsmith things where, so often where he pulls back, and really, you’re just dealing with two lines—there’s the melody line, and just a counter line, there’s no real harmony and everything’s implied, and I’m saying, “Okay, how can we even reference that and say we want to call back to that and the way it weaves through?” And so even when Jack gets his idea at the end, there’s a callback to the [ Voyager ] synth theme. I think it gave the studio a bit of a nightmare on the cue sheet because it’s like nine segments. And I think on the soundtrack that’s actually just gonna be listed as like eight Star Trek themes in the space of 90 seconds. And it was a challenge to make it make sense as well and not just feel like, “press button, press button…” I think if anyone’s going to criticize us, I think there’s just the thing of something Terry and I chatted a lot about, which is what would Jerry Goldsmith have done on the sequence? He has these great themes, and I think he probably would have gone to the approach of doing a million other things, and they would have pushed him back and said, “Well, we just want to hear the Voyager theme when you see it with Seven, so, please give us that.” But then he would have done it with consummate class. And that’s obviously the highest bar you can get, and I think in 25 years’ time, someone will say whether we reached that or not, but we certainly are not the ones to be the judge of that. So we’re just trying to do as well as we can.

The Fleet Museum brought back a lot of themes

I was getting choked up during the museum sequence. It is very literally fan service but it’s done very well and tastefully, and especially after everything else that has been built up it works beautifully. When I first started watching this I was initially kind of groaning because it seemed like it was diving so deep into, “we’re gonna do the lost son from Wrath of Khan .” And by the time I got to episode three or four, it all just was working so well, that I really felt like, “Okay, now they’ve earned all this.” And it stops becoming just, we’re gonna throw references to the fans, and it becomes much more like affection, and kind of earning all that and using it and in a really moving way. And the scores are a big, huge part of this. And it’s not just all the references, it’s the approach, the dynamic approach of having real action music and having big commercial playouts and all those things we associate with the older movies and shows.

Barton: Freddie has, without spoiling anything, a cue in episode seven that I think is eight minutes long or something, and it’s one idea. We were into the last three, four weeks, and we still have this pile of music to write, but it was one of those ones where you look at the sequence, and there’s no tracking, there’s no editing that can get you through this sequence. And that’s true of all of the back four episodes, seven through 10. I think that was the other thing we were very much thinking about when we were doing a lot of the action music. And Freddy and I chatted for quite a bit about this: the pacing, particularly when he gets to the final episode is like, how would you get bigger? How do you find places to pay this off? Funnily enough, a lot of where we found the answers to that was in the Goldsmith stuff. Because I think one of the Goldsmith hallmarks is his ability to use silence and his ability to write something big and massive. He’s a master of huge textures, but also a master of when to shut up and let something play. And so in all four of the final episodes, I think there are times we both realized you just pull back and you just let a moment be a moment, and you just be confident that we have the performances and we’re not trying to apologize for anything in terms of the production. The other thing we have is the visual effects are so much better now. We’re never trying to tell you something looks awesome because it probably does. And I think that a lot of the reason for modern film scoring and action scoring being the way it is, is because you see something so amazing on the screen. It’s almost like people are like, “Yeah, you don’t really need to add to it.” Whereas what you can do is realize that that’s not the total idea. The idea is, it’s okay to paint big themes around there, provided you do it in the right way and from the right perspective.

Wiedmann: I think this goes back to another question you had earlier, about new themes that I can’t talk about much. But there is a Jack Crusher idea, a musical idea that comes in the later episodes as his relationship with his father becomes more and more distinct. And his performance was so on the spot every single time that it just felt like you don’t want to do anything. So the theme for him in those particular ones is extremely subtle because he just does it all. So it’s really just very subtly supporting what’s going on, but the performance is so strong that you really don’t want to overstep that. There are so many instances of that throughout the whole season. I think that we’re almost like, “Let’s not break it.” Because it’s so good to begin with.

Frederik Wiedmann at a Picard scoring session

Yeah, that’s something I think people who didn’t grow up on it don’t understand about the older movies and television is that the music was the special effects and it was the sound design on a lot of these things. Before you came up with all these layers of Dolby sound and super sophisticated visual effects, the music had to sell all that stuff. And so it wound up doing so much more dramatically than you necessarily have to now. So what can you tell me about the soundtrack?

Barton: I think it’s about two and a half hours. That was a pretty heavy cull down from five hours. But I think we very much also wanted it to stand up as a listening experience in its own right. Gordy and I have Star Wars , we have a three-and-a-half-hour soundtrack. And at that point with these things, I’d be honored if anyone ever listens to it from start to finish. That’s the nicest compliment I think anyone could pay. But I think what we tried to do is to make it make sense. The funniest thing about the soundtrack is we didn’t cut it. And that sounds terrible. Terry cut it. We presented him a draft and we were chatting about it. And then the following morning, he’s like, “Yeah, I stayed up all night and cut this together,” and gave us a spreadsheet. Not only is he incredibly musical, he actually loves sitting at the back of the room while I write. He just loves it and will actually weigh in with suggestions. And most composers, I tell them that and they go white, and they’re like, “Are you kidding? The director’s in the back of the room while you’re writing, are you insane?” But he’s got such a good sensibility for it. And he’s not someone who says, “Yeah, go up, now go down,” or something like that, but he’s like a rather good composition teacher in a way without knowing it. Without having a background in music, he asks questions and says, “Well, is that theme, does that feel satisfying?” One of the things he often talks about is he wants his music to commit. And I think that’s what sets him apart from a lot of filmmakers in terms of how they handle music. He likes the music to go there. He’s like, “Commit to what you’re doing. Commit to shutting up, if you’re shutting up—get out, don’t leave some little pad.” He’s like, “Just shut up. Don’t be afraid to make the bold choices.” So that’s very much his directorial style. So he cut the soundtrack together, literally put it together and we listened through but I think we changed one track.

I’ve been into this music since I was a kid and it’s very much waxed and waned in terms of how much fun it is. This is very fun. And it definitely feels like something I want to listen to outside of the show and it helps drive the show and make it exciting. So, all props to Terry for being someone who wants that. Because it seems like filmmakers over the past few decades have been very conflicted about whether they actually want music as a real contributor, as a character, as opposed to just filling in the silence.

Barton: I think there was a process that filmmaking went through in the 2000s, and particularly with the boom of digital cameras, digital cinema, and the speed at which the process and the difference between the editorial versus where it’s gone to the Avid, and now we have the online and the offline and there’s the whole process of filmmaking. I think people thought we were going through a growing-up period where less music is more, and undoubtedly films were “less music is more,” and undoubtedly films did take the approach that the filmmaker wants that. That’s their prerogative. Now we’re passing through that and we’re getting to a place where it’s okay to be musical again. And I listen to a lot more scores now and hear a lot more scores where I actually like the music. And I think where it goes in the next 10 years will be very interesting. I think we’re starting to come to a place now where all of those languages are okay, provided you know what you’re doing with them. And so people are coming back to it and saying it’s okay to be melodic, it’s okay to have tunes, it’s okay to develop them. It’s okay to have a theme and call it something and have a leitmotif. That’s okay, again.

Wiedmann: One thing this whole experience working on this show taught me is there’s a lot of film music from 25 plus years ago, when you listen to it today, and you go, “This is not really what we’re doing anymore. This doesn’t really go with today’s aesthetic of moviegoers.” But anything that Goldsmith did, however old it may be, I think it holds up like nothing else to today’s standards. There’s nothing old or old-fashioned or cheesy sounding about it. It’s just like, “Holy crap, this is so fucking great.”

Barton: It’s taken 25 years to realize that.

Soundtrack announced

Lakeshore Records has announced they will be releasing the soundtrack for season 3 of Star Trek: Picard , containing 45 tracks . The digital release will arrive on April 20, the day of the season finale in April. You can pre-order the soundtrack on Vinyl for $35.98 , coming on May 12.

Jeff Bond is the author of The Music of Star Trek . He co-produced the 2012 15-disc box set of all the music from the original 196 6 Star Trek series and has written liner notes for releases of all the original Star Trek theatrical films from Star Trek: The Motion Picture to Star Trek: Nemesis .

Related Articles

Discovery , Interview

Interview: ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Writer Carlos Cisco On Unmasking The Breen And Revisiting The ISS Enterprise

DS9 , Lower Decks , Star Trek: Picard

Michael Dorn Wanted Armin Shimerman To Play The Ferengi That Worf Killed In Star Trek Picard

Lower Decks , Section 31 , Star Trek: Legacy , Strange New Worlds , TNG

Jonathan Frakes Sees Opportunities With Streaming Star Trek Movies, Weighs In On “Filler Episodes”

Interview: Sonequa Martin-Green On Facing Her Past On ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ And Her Hopes For The Future

I would prefer more originality across the board myself

Agreed. It’s one thing to celebrate the franchises music, but this is a patch-work quilt of music written for entirely different scenes, characters, what-have-you. Can come over as leaning too much on prior musical greatness rather than doing something original that stands on its own two legs. It’s great to see the love and reverence for the scores however, and it’s incredibly well done. But it just seems an odd season/show to suddenly decide to celebrate Trek’s filmic music in particular, rather than it being a special Trek Anniversary or something. Too much reliance and memberberries!

Ditto. I don’t know why, but it really bums me out that they’re using the First Contact theme as the end theme — and I *love* that theme. But it just feels out of place and, well, borrowed/recycled here. I’d almost prefer the previous Picard theme (which wasn’t perfect). Or a new theme using some of the FC cues.

It’s kind of like how I felt the TMP theme for TNG. It’s one of my favourite movie themes, yet it never felt like it fit the show to me.

I thought combining the TOS theme and TMP theme to create the TNG theme was inspired. It easily became my favorite Star Trek theme. The classical opening narration continued Space The Final Frontier, and the music swells up. Just brilliant.

with all of these former “12 Monkeys” alum showing up on Picard, the one I would most like to see is Emily Hampshire ($chitt$ Creek)

She would be a wonderful addition. Shaw’s ex-wife, another captain, the event planner for Frontier Day, anything.

That would be awesome. But she’s a regular on” The Rig”, filmed about the same time as Picard. So it’s a slim chance at best.

It would be fantastic her and/or any number of 12 Monkeys alumni in addition to those who’ve already appeared. I just finished that show this week. One of the all time great series finales.

I was very much hoping Matalas would bring Hampshire into Trek as well.

Hopefully, he’ll have the opportunity to create as rich and wonderful character for her in a future show, limited series or movie as he did for Stashwick.

And yes, putting Stashwick and Hampshire back together in a scene would be the chef’s kiss.

Another captain would be nice. I want Shaw to be LGBTQ+.

Yep, also agree. I think she was the first person a lot of people thought of who would be involved in this season, even if it was for an episode.

I’d like to see Amanda Schull!

The score is wonderful. Plenty of legacy and plenty new that fits. I just love it all.

Same here. It’s magnificent.

Completely agree. It’s a fantastic score and I love it.

This was a very interesting read but I have to admit, I read the part where Barton was talking about composing for Star Wars and got very confused because when the interview said “Gordie Howe” my brain went “like the NHL player?”

Ha, you HAVE to be Canadian to know that name!

That’s what leapt to my mind also . ;)

No, American, but one of my headmates is Canadian and passed on his love of hockey to me. So I learned a lot about it, including about former players of some kind of note.

Picard season 3 has a great score so far. Job well done on that part . Just thinking about it even the weaker Trek movies are worth watching just for the score alone sometimes. I can just close my eyes , when one of the bad or boring bits crop up ,and just get enveloped by the music.

Absolutely!

Good point. I find this true as well. Generations and Insurrection , specifically.

My unpopular opinion is that I think that Star Trek III is the most under-rated Star Trek movie. It’s far from the best, but far from the worst. I love the music in that movie.

BTW: I noticed the TVH score played a bit when they showed the Bounty BOP in the previous episode.

To be honest, it’s probably the best “odd” Star Trek movie.

Found Matalas’ burner account!

Kidding aside, while this is an unpopular opinion, it shouldn’t be.

I absolutely love ST III, and have since seeing it in theaters. Sometimes I watch it even without watching WOK first. (But usually watch the two as one long movie).

Horner’s score for Star Trek III is my favorite of all the Trek movies new or old. Don’t get me wrong, Goldsmith’s score for The Motion Picture’s is amazing as is Horner’s work on Wrath of Khan. But, Search for Spock just rises that much more above in my book.

Your post just described my total viewing of TMP lol.

Star Trek 5 has awesome music despite the flaws of the film itself.

Awesome score so far on this show, definitely the best we’ve had in all of New Trek including the alternate timeline movies. I especially like what he’s saying about the Voyager theme in regard to Goldsmith’s restraint, and that it basically just has two lines and little harmony… but what they did with the theme *harmonically* for the museum scene was fan-tas-tic: it was just a few small harmonic tweaks (with a modified repetition of the three-note Voyager motif at the end), but it didn’t just make it weave through the scene, it really opened up the theme itself, made it deeper & more nuanced, and underscored Seven’s emotional state very well in that moment. That scene, in a masterful way, went far beyond fan service, and the composition was a big part of that success. Some absolutely brilliant composing for this season, for sure.

Just a quick word to praise this wonderful interview. It had great questions that elicited substantive and fascinating replies. Thank you!

Seconded. Great questions that really let these artists let loose.

Yes, thirded. Substantive discussion, no softballs.

For some reason, every time I hear a musical reference to the TOS movies, it takes me right out of the show. It’s like the auditory equivalent of seeing half the Titan’s crew wearing Monster Maroons instead of current uniforms. For whatever reason, I don’t think of it as “Star Trek” music, but as a historical signifier. I suppose it’s nothing more than a “me” problem in the end.

I feel the same.

The music is great

I’m am glad we are bringing back some awesome themes vs. the wallpaper music of TNG/VOY. Even the TNG theme was a watered down version of the TMP theme. Apart from the Borg music in TBOB I feel for the musicians as hard to utilize such forgettable music, glad to see they’ve decided to embrace the memorable TOS movie cues.