RIDER STYLE Single Tack

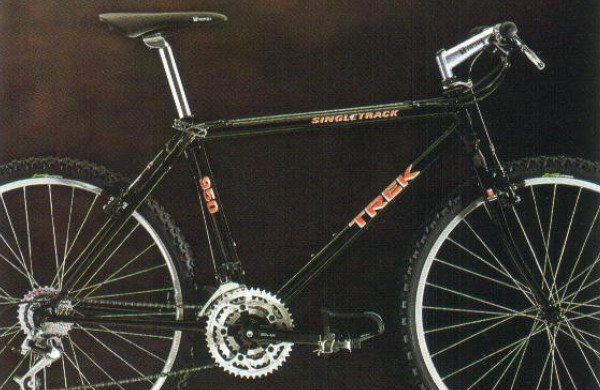

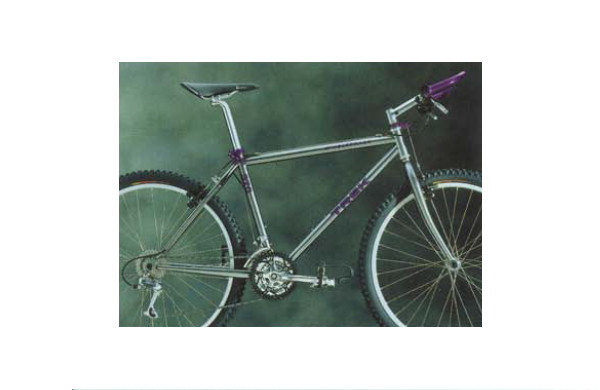

The 1991 Trek 990 is a competition bicycle for the off-road enthusiasts that demands the most from a bike. Featuring a True Temper heat treated single track OD Cromoly frame with the Tange Super Big Fork, the construction and aggressive geometry of this frame creates the responsiveness, rigidity and strength that is necessary for aggressive off-road riding. The Shimano Deore XT drive train and Matrix Single Track Comp rims provide stable performance in an often challenging terrain.

MTB CATALOGUE All models

All 1991 models, all catalogues, original specs for this model.

Frame Fork Handlebar Rims Hubs Pedals Brake Set Derailleurs Cassette Chainrings Cranks Seat Stem Tyres

TTempr OD CRMO Super Big Fork M Easton Alloy Matrix STrackC S Deore XT 32H Shim Deore XT S Deore XT Ct Shim Deore XT S HGlde 12-28T S DXT 46/36/24 Shim Deore XT Selle Turbo Matrix OS Matrix Z-Axis

Tioga Avenger

15/16.5/18/20/22

Fork Travel

Original Colours

Gallery Bike by @re-rides

Content © mountain bike catalogue document.write( new date().getfullyear() ); . contact. site by pxxl..

90s Trek MTBs - Steel frames, rigid forks, 26" wheels

Full list of steel, rigid fork mountain bike models Trek made between 1990 and 1999, grouped by year, containing details on frames and main components for easy reference.

Based on riding style, build level and performance, Trek offered these in two series. The 9XX series , called Single Track , consists of a range of race, competition and performance bikes, aimed at pro riders and serious off-road enthusiasts. The 8XX series , called Antelope until 1993 and Mountain Track from 1994, covers a range of multipurpose models, from commuting and recreation to trail and light mountain biking.

1990 View catalog

Trek 990 Single Track (1990)

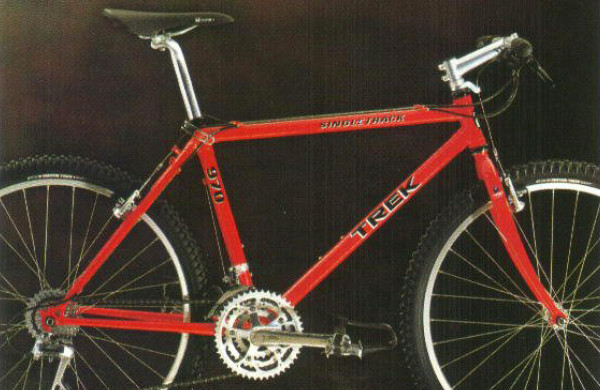

Trek 970 Single Track (1990)

Trek 950 Single Track (1990)

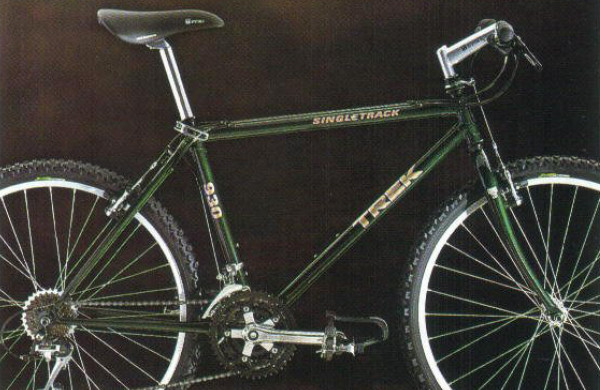

Trek 930 Single Track (1990)

Trek 850 Antelope (1990)

Trek 830 Antelope (1990)

Trek 820 Antelope (1990)

Trek 800 Antelope (1990)

1991 view catalog.

Trek 990 Single Track Competition (1991)

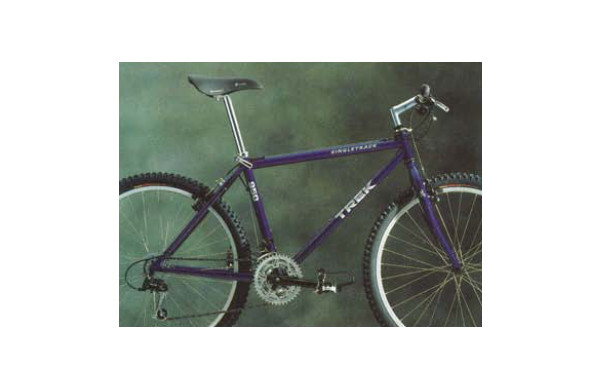

Trek 970 Single Track Competition (1991)

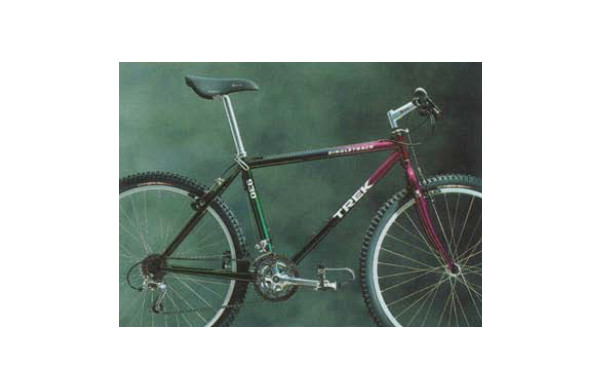

Trek 950 Single Track Performance (1991)

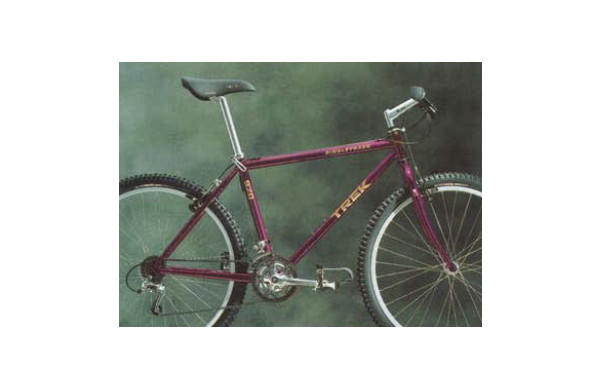

Trek 930 Single Track Performance (1991)

Trek 850 Antelope Performance (1991)

Trek 830 Antelope Mountain Sport (1991)

Trek 820 Antelope Trail Performance (1991)

Trek 800 Antelope Sport Trail (1991)

1992 view catalog.

Trek 970 SingleTrack Competition (1992)

Trek 950 SingleTrack Performance (1992)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1992)

Trek 850 Antelope Performance (1992)

Trek 830 Antelope Trail Performance (1992)

Trek 820 Antelope Sport Trail (1992)

Trek 800 Antelope Sport Trail (1992)

1993 view catalog.

Trek 970 SingleTrack Competition Race (1993)

Trek 950 SingleTrack Performance (1993)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1993)

Trek 830 Antelope Performance Trail (1993)

Trek 820 Antelope Sport Trail (1993)

Trek 800 Antelope Sport (1993)

1994 view catalog.

Trek 970 SingleTrack Competition (1994)

Trek 950 SingleTrack Performance (1994)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1994)

Trek 920 SingleTrack Performance (1994)

Trek 850 Mountain Track Performance (1994)

Trek 830 Mountain Track Performance Trail

Trek 820 Mountain Track Sport Trail (1994)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Sport (1994)

1995 view catalog.

Trek 990 SingleTrack ZX Series Competition (1995)

Trek 970 SingleTrack ZX Series Performance

Trek 950 SingleTrack Performance (1995)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1995)

Trek 850 Mountain Track Sport (1995)

Trek 830 Mountain Track Sport (1995)

Trek 820 Mountain Track Recreation (1995)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1995)

1996 view catalog.

Trek 990 SingleTrack ZX Series Competition (1996)

Trek 970 SingleTrack ZX Series High Performance (1996)

Trek 950 SingleTrack High Performance (1996)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1996)

Trek 850 Mountain Track XC Enthusiast (1996)

Trek 830 Mountain Track XC Enthusiast (1996)

Trek 820 Mountain Track Recreation (1996)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1996)

Trek 800 Sport Mountain Track Recreation (1996)

1997 view catalog.

Trek 930 SingleTrack XC Series Performance (1997)

Trek 850 Mountain Track XC Series Enthusiast (1997)

Trek 830 Mountain Track XC Series Enthusiast (1997)

Trek 820 Mountain Track Recreation (1997)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1997)

Trek 800 Sport Mountain Track Recreation (1997)

1998 view catalog.

Trek 920 SingleTrack Performance (1998)

Trek 820 Mountain Track Enthusiast (1998)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1998)

Trek 800 Sport Mountain Track Recreation (1998)

1999 view catalog.

Trek 820 Mountain Track Recreation (1999)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1999)

Trek 800 Sport Mountain Track Recreation (1999)

Acronym for all terrain bike.

Trek's exclusive fork design.

A tube having different wall thicknesses along its length, while its diameter remains constant.

Low alloy steel with a medium carbon content, that gets its name from the primary alloying elements, chromium and molybendium. It has an excellent strength to weight ratio and is considerably stronger, harder more durable than mild carbon steel.

Trek's exclusive fork design using taper gauge tubing and provides a blade with more elasticity for better shock absoption.

The thickness of the tube at both ends is thicker than in the centre.

Shifting system, where part of the handlebar grip rotates back and forth, clicking into each gear.

Low alloy steel that can withstand significant stress before breaking or becoming deformed. The term 'tensile' refers to the amount of stress a material can endure before failing.

Steel tubing connected with socket-like sleeves, called lugs.

Shimano's multi-condition brake system with specialized shoes, levers and cables designed for enhanced stopping power in rain, mud and snow.

A house brand for Trek during the 80s and early 90s.

Optimal Dimension; Trek's large diameter, thin wall tubing design.

Oversize; Trek's large diameter, thin wall tubing design.

Shimano's oversize hub system designed to minimize wheel flex.

Shimano's under handlebar, two-finger shift system, giving riders the ability to downshift more than one gears in one stroke.

Brake lever system that lets riders adjust braking power modulation.

Shimano Integrated Shifting. Shift mechanism indents control cable advance for quick, precise gear changes without over-shifting.

Shimano Linear Response. Friction reducing levers, cables and calipers.

Japanese steel tubing manufacturer for bicycle frames.

A tube having a maller diameter at one end and a larger diameter on the other end.

Tungsten Inert Gas welding is an arc welding process that produces the weld with a non-consumable tungsten electrode.

Trek-designed components. The higher the number ona given component, the higher its performance level.

Three different wall thicknesses along the length.

American tubing manufacturer.

Special all-terrain tubing, developed to withstand demands of off-road cycling.

A lighter weight version of the AT frame set, featuring a triple-butted down tube.

Zero Excess; Trek's guiding principle of making stronger bikes with less material.

Related posts

Vintage Trek Catalogs

Table of Contents

Here you can find all the Trek catalogs from 1976 up to 1999. If you’re looking for a specific model for a specific year, you can find them further in the article.

Trek Catalogs

- Trek Catalog 1976

- Trek Catalog 1977

- Trek Catalog 1978

- Trek Catalog 1979

- Trek Catalog 1980

- Trek Catalog 1981

- Trek Catalog 1982

- Trek Catalog 1983-1

- Trek Catalog 1983-2

- Trek Catalog 1984

- Trek Catalog 1985All-Terrain

- Trek Catalog 1985Trek2000

- Trek Catalog 1985TrekRacing

- Trek Catalog 1985TrekSport

- Trek Catalog 1985TrekTouring

- Trek Catalog 1986

- Trek Catalog 1987

- Trek Catalog 1988

- Trek Catalog 1989

- Trek Catalog 1990

- Trek Catalog 1991

- Trek Catalog 1992

- Trek Catalog 1993

- Trek Catalog 1994

- Trek Catalog 1995

- Trek Catalog 1996

- Trek Catalog 1997

- Trek Catalog 1998

- Trek Catalog 1999

History and Iconic Models

Trek started out in 1975 by providing only frames. In 1976 they would supply entire bicycles.

For many people Trek is most famous for sponsoring Lance Armstrong’s U.S. Postal team during the late 90’s up to his retirement.

But Trek already pioneered the use of carbon fiber in 1989 with the Trek 5000.

It would result in the short-lived but daring design of the Y-Foil, introduced in 1998. One of the few bikes that is designated with something more than just a number.

They were also early adopters of the mountain bike craze, with the Trek 850 launched in 1983.

Their early foray in using carbon fiber would be later used with the introduction of the iconic Y33 and Y22 models. Mountain bikes with a monocoque carbon fiber frame. Although it used the suspension technique URT ( unified rear triangle ) which would turn out to be rubbish, the original design was considered iconic.

If you’re interested in learning more about vintage Trek bicycles, please visit vintage-trek.com .

Trek Models

Mountain bike, you might also like.

Vintage GT Catalogs

Here you can find a selection of GT catalogs from 1990 up to 1998. If you’re looking for a specific model for a specific year,

Vintage Kona Catalogs

Here you can find all the Kona catalogs from 1989 up to 1999. If you’re looking for a specific model for a specific year, you can

Vintage Giant Catalogs

Unfortunately I was only able to find a couple of Giant catalogs. Although it’s a huge bicycle brand, finding the Giant catalogs proved to be

Vintage Cannondale Catalogs

Here you can find all the Cannondale catalogs from 1983 up to 1999. If you’re looking for a specific model for a specific year, you

Barnevelderstraat 17 1109BX, Amsterdam the Netherlands +31 618 744 920

Quick Links

- Search forums

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

- Mountain Bike --> 1997

- Reader's MTBs --> 1997

1991 Trek 990

- Thread starter GeneralOsik

- Start date Nov 12, 2021

- Tags 1991 990 conch tioga trek

GeneralOsik

- Nov 12, 2021

- Nov 26, 2021

Attachments

Prodigal Son

Senior retro guru.

- Nov 27, 2021

Back in the day, a wealthy neighbour bought one.. Guy was a lawyer for corrupt politicians and had also a fleet of expensive cars. I used to admire the bike and had no funds for a high end mtb. Then i read a test (was it bicycling?) saying the frame was a brick and the stumpjumper was the real deal. Anyways, i bought a 8700, new, at the dealer, a couple years later and hated it´s dead feeling ride from the go. I bet the steel 990 is way better....

- Nov 28, 2021

Prodigal Son said: Back in the day, a wealthy neighbour bought one.. Guy was a lawyer for corrupt politicians and had also a fleet of expensive cars. I used to admire the bike and had no funds for a high end mtb. Then i read a test (was it bicycling?) saying the frame was a brick and the stumpjumper was the real deal. Anyways, i bought a 8700, new, at the dealer, a couple years later and hated it´s dead feeling ride from the go. I bet the steel 990 is way better.... Click to expand...

- Nov 30, 2021

- Apr 15, 2022

- Apr 16, 2022

- Jun 3, 2022

Similar threads

- Once A Hero

- Sep 2, 2023

- Mar 19, 2024

- Nov 20, 2023

- Mar 25, 2024

- Feb 10, 2024

Latest posts

- Latest: Dogboy

- 23 minutes ago

- Latest: Nob

- 34 minutes ago

- Latest: mmmtb

- 59 minutes ago

- Latest: d8mok

- Today at 03:02

- Today at 03:01

- ALL MOUNTAIN

- ACCESSORIES

- ALL (130 Forums)

- WHEELS & TIRES

Trek 990 Bike 1998 or Older

- USER REVIEWS

Light weight, beautifully constructed lugged frame, high quality, amazing paint, wonderful steel frame ride, made in the USA.

They don't make this frame anymore.

I bought my 990 as a used frame off eBay and just got it built up and finished. It didn't have much use or wear and it rides so nicely. It handles well with an 80mm front fork and it very stable. It feels like it helps push you up hills. It's too bad you can't buy a reasonably priced, high quality steel frame like this nowadays. It has all the bosses you need if you want to mount frenders or a rack. The frame is very light for a steel frame, there are no downsides to it. It makes for a really nice riding hard tail. [IMG]http://i71.photobucket.com/albums/i148/rock_rider/Mobile%20Uploads/image_zpseihhduri.jpeg[/IMG]

great balance, strong, yet light frame

Front pull brakes a bit jumpy

I bought this bike in 1992 and have hammered it on many single tracks in Colorado for the last 20 years. Best $1,100 I spent 20 years ago

I purchased it new in 92. I had bought a Specialized Stumpjumper team used and the insurance company that was replacing a recently stolen bike wouldn't pay for a used bike so I HAD to buy new. The thought of spending $1000 on a bike at the time was outrageous. It turns out that was the best money I have ever spent. I have about 45,000 miles on this bike and willl not give it up. I have owned other boutique bike since but always go back to this bike. It may not be as fast as the my Ellsworth downhill but it is more fun. I like the feel of the hardtail and the excitment of keeping keeping it controlled. I can go much faster on the full suspension bikes but the error margin is significantly smaller as the speed increases. This bike has a very large sweet spot and it is easy to know when one is approaching the limits. This is an important factor for me since taking on the responsiblity of fatherhood but not being willing top give up the mnt biking like may people suggested. I love this bike so much I bought a smaller version my son will grow into in 5-6 years and hope he enjoys it as much as I do.

The front brake arch is week and flimsy. I replaced it with a carbon one off the Mogul. The original shock isn't very responsive to wash board but handles the big stuff well enough.

This is a fantastic bike and the one I ALWAYS go back to. It still looks new and gets alot of attention.

Similar Products Used:

Ellsworth Truth, Specialized Stumpjumper Team (great bike also), Bidgestone RB-1, Gary Fischer Hoo Koo E Koo

Smooth, confidence inspiring XC ride. Climbs great and you can throw it around to work through most anything.

None really. But I've upgraded it extensively over the years.

I’ve had this bike since 1993 and love it. I picked it up on closeout since it was a year old. At the time, it was one of the nicest Mountain Bikes on the market in its price range. It is beautiful with a triple butted, lugged, XO True Temper frame and good quality components. I think I paid around $800 for it then. For most of its life I’ve used it as a fire road bike and for a while as a commuter. In September 2009, I started riding single track again and started modernizing the component set, but still keeping in the spirit of the original bike. Last week I finally swapped out the original DS2 fork with a new Manitou R7 100mm. Oh - my - god. This bike climbs like a bunny and descends with confidence. Here is a photo: http://flamencohead.com/flamencohead/index.php?/wiki/1992_Hardtail_Trek_990/

Santa Cruz Superlight

I've had this bike since 1996, it was the sweetest spec'd bike I had seen at the time, and I even liked the color. It handled as well as a '96 Rocky Mountain Blizzard, but it felt less 'twangy' (probably from Rocky's use of Tange Steel at the time) but since the bike was on clear out from Trek due to delays that year of the Manitou Mach 5 SX, which was experiencing initial teething problems with the bonded arch/lowers. For a $700 (CDN funds) I couldn't say no. I've had my 990 ever since.

I haven't come across any yet (knock on wood) I've had it for 13 years and counting! if I were to nit pick, I'd say the Dia Compe PC 7 Levers at the time were 'meh', and I swapped out the SRAM X ray shifters pretty quick too. Plus the front hub on the front wheel was a glossed up Joy Tech hub... that went to crap in 6 months.

I've had it since 1996. I love this bike, I have had quite a few bikes in my stable over the years, and I sold off almost all of them. It climbs nice, dampens rough trails, and handles really well in the technical and the fast stuff. This bike has been all across canada, and when I stop by bike shops of years past, they can't believe I still have it. They called it 'old school' last year in Edmonton. I agree, it is old school and it stays true to the motto 'they don't build 'em like they used to!'

nothing like it!

Great looking bike. Lugged True Temper, DX with XT shifters, stiff, light, and responsive.

Original rims are weak, or seems that way since the back rim on mine has a bad hop. Still riadble though. Other than that, NONE. Thinking of a Rhyno Lite swap.

LOVE this bike, and I have not even been offroad with it. Best looking MTB I have ever seen, bar none!! Most of the newer stuff looks ugly to me, to the point of repulsive, lol! Fire engine red lugged frame with black and white graphics. The original suspension fork is almost dead, but still works fine for street use. This bike is the lightest steel MTB I've owned too. I have vintage road bikes that weigh more! It also moves like no other, even on pavement with WTB knobbies! You keep the cadence up, and it scoots! If you can find one of these gems in good shape, snag it. Mine was a lucky find, it only looks a year or two old at 14-15.

Schwinn High Sierra, Cannondale. Both late 80's though.

light, strong--ox comp iii triple butted, best paint job possibly ever on bike

don't make it anymore

still going, and this thing gets more complements than my 4000 mountain bike. I have been reviewing and trying products for years, and i would still protect this thing with my life (now another 1500 invested). As for the guy below me, learn to spell. There are no fantasies here buddy, no reason to lie, this is the bike that does it all for me, cyclo race, xc race, commute, passing by chumps that make fun of other bikers...see you on the street...ill be riding the trek thats grey...if you ever see one of these buy immediately

Strong, great single track bike. I locked it up outside for three months it went through the rain, and I thought I would need to buy a new bike. But I put a new chain on, lubed her up, and she rides as fast as ever.

A little heavy.

This bike is great I'm faster than all my friends with XC dual suspension bikes, down hill, and on single track. I have the gun smoke grey, I love the way it looks very subtle. This bike flies. I really want to buy a new bike bc I'm looking to get my girlfriend one, but then I always remember that I don't want a new bike, this bike is giving enough not to beat you up, but rigid enough to put all your power down to the dirt. I've thought about getting a full suspension bike but don't like how soft the ride is, I feel like I driving a '80's Cadilliac way to plush. This bike feels like a Porshe. Great bike.

GT Avalache, Trek Y (crap), Litespeed (I didn't like it as much even though it was lighter)

It is lite for a chromo set-up. The Troy Lee Design graphics make this bike one of a kind. I know I will never run imto some riding this same bike.

I am priveledge to ride this bike for free. The stance is much more aggressive than most standard MTB. At $1200+ in the early 90s, this would be one expensive bike today. One great ride for anything. This bike should have been made from gold but that may have been to heavy!

K-2 Zed X and a Specialized Stumpjumper.

Bought this frame back in 1998. It has been with me, in various incarnations, until 2005, when I gave it to my girlfirend. It has been a stout performer. Stable, ballanced, snappy, but never twitchy, and just a joy to ride.

I had one of the riv-nuts pull out of the seat tube bottle mount, but other than that I've never had any problems. Biggest weakness? Trek no longer makes a high end steel frame hardtail any more.

"Date Reviewed: 2/17/1998 Bottom Line: I have only logged 18 miles on my 990, although I have had good saddle-time on my friend's spare 970. This bike is a definite wolf in sheep's clothing. All of my past bikes have been aluminum, and I had pretty much sworn off steel (Its' sooo heavy.)to this point. 990 heavy? No way! This thing's a blast. The frame is Tig welded OX III Triple butted Cro-Mo, so compared to same size aluminum frames it is heavier. Not by more than a 8th of a pound though. What this frame's got is ballance. Very stable, easy to control, almost predictable in its character. An absolute dream to ride. This frame's got a good racing history behind it too. I bought it off a good friend, who's wife had raced it acouple of seasons. It's as stout and clean as the day it was made. I am looking forward to racing it this season, and many more. I've been racing xc for almost 6 years, expert the last 2, and I've ridden and broken just about every kind of frame out there. I feel very confident that this one won't die an untimely death.Oh yeah, the specs... It' an 18 with xt ders, raceface cranks, syncros cro-mo b/b, judy sl w/ speed springs, mavic 217cd's-white ind. hubs-dt 15/16/15 spokes, syncros hardcore seatpost, titec beserker ti k saddle, xt rapidfire, avid 1.9L levers and xtr v brakes, and avid flak jacket cables. No silly ti bolt kits, or other little trinkets that snap an the worst possible times. Weight: 24.3lbs. I highly recommend this bike/frame, if you can get your hands on one. They're grrreat!!!" As you can see, this bike's been with me for a little while. It's been raced, out on epics, commuted and done courier work with it, and just all around loved. I hung up the bikes for a few years...burned out... then moved to San Francisco with a new job. Some of my coworkers were recreational riders, and got me to knock the dust off the 'ol steeds. And I rediscovered mountain biking all over again! The 990's since done hundreds of Trips For Kids rides, a hard couple of days in Downiville (keeping pace with long travel dualies I might add), zipped all trhough the urban terrain, night rides on Mt. Tam, and then came with me when I moved to Portland. And, yes, it's just as stellar in the soggy Pacific NW as it was in down in Austin, TX!! I rebuilt it with some old race parts, got it a new set of wheels, and gave it to my girlfirend for her birthday. She loves it. It's mainly commited to bike paths and around town, but it's still riding strong!! All in all, it was probably one of the greatest bikes I've ever owned. The last of a dying breed... a steel frame, from a big company, that was as nice as any custom I've ever ridden.

Get the latest mountain bike reviews, news, race results, and much more by signing up for the MTBR Newsletter

Hot Deals See All Hot Deals >>

- CLASSIFIEDS

- TERMS OF USE

- PRIVACY POLICY

- ADVERTISING

VISIT US AT

© Copyright 2024 VerticalScope Inc. All rights reserved.

- This topic has 6 replies, 5 voices, and was last updated 12 years ago by xcentric .

- Retro Trek 990

Evening all, looking at selling a 1991 Trek 990 (currently the donor bike in case the garage gets broken into). It’s full XT (thumbies), rigid forks. Will either ebay or Retrobike. Any ideas of value?

No idea of a value myself but I’d def have a look at the Retrobike site, particulary this thread to get a value.

Are you still selling it. What size frame? Did you decide on a price? Where abouts are you?

Please enable JavaScript

Just cleaned the dust off it. 16 inch and i’m in Coventry. Still thinking about the price!

If it sells, please post how much you got for it, I’ve got a Trek 950 from a similar era which I’m thinking about selling.

It’s a difficult one, nearly all original a few extras, full XT. Was hoping for £400?!

blimey. I’ve got a 970 original, plus upgraded shifters (XT) and didn’t reckon it was worth more than £40, after checking ebay etc…..

The topic ‘Retro Trek 990’ is closed to new replies.

- Forum Listing

- Marketplace

- Advanced Search

- Community Help Section

- Archived Discussions

surly troll fork on a trek 990?

- Add to quote

Hi , I'm new and this is my first post , sorry if I make a mistake . Buy a trek 990 and I want to put a surly troll fork. I know that the best option is the surly 1x1, but it is so wrong to use the troll ?

What year is your trek? Before 1994 the trek frames were not suspension corrected and they were 1994 and after. The surly troll fork is a suspension corrected fork so if you have a 1994 or newer trek it should work ok. The original fork on my 1991 trek 970 fork (same frame as the 1991 trek 990) has an axle to crown of about a 390mm (rough measurment), but the surly troll fork has a axle to crown of 453mm so the surly troll would not be a good match for my pre 1994 frame.

Hmm, if yours has the ds2 fork then the surly troll fork will probably keep things similar. I am guessing the ds2 had about 2 inches of suspension so that would make the frame sit about the same as the surly troll fork. I figure the rigid fork was about 390mm axle to crown, then add 2" or 50mm of suspension gets the ds2 about bout 440mm or so. That's not too far off from the troll. Do you still have the ds2 fork? If so measure the axle to crown and that will let you know how the troll will fit. If it is still on your bike and you have a smart phone you can download an angle measuring app and get a rough idea of what the head tube angle is with that fork. FYI, with the ds2 fork the head tube angle probably ran about 69 degrees or so vs 71 which is what it would be with the rigid fork. They just threw suspension forks on frames back then and didn't really think about how it changed the geo until the mid 90's.

- ?

- 15.5M posts

- 516K members

Top Contributors this Month

SORT CONTENT BY LOCATION

CLICK TO DRILL DOWN BY COUNTRY/PROVINCE

Your browser is ancient! Upgrade to a different browser or install Google Chrome Frame to experience this site.

Inspiration

- Bikepacking 101

- Join/Support

- View Latest/All

- Bikepacking Videos

- Your Stories

- Rider's Lens

- Field Trips

Popular Tags

- #bikerafting

- #Tour-Divide

- #family-bikepacking

- #winter-bikepacking

- #1Q5V (1 Question 5 Voices)

Gear/Reviews

- Bikepacking Bags

- Camping Gear

- Accessories

- #Editors-Dozen (Our Favorite Gear)

- #Gear-of-the-Year

- #MYOBG (DIY)

- #Decade-in-Review (Best of All Time)

The Gear Index

Latest indexes.

- Mini Panniers

- Saddlebags & Top Openers

- Cargo Cages & Anything Bags

- Gravel Bars

- Drop Bar 29ers

Bikepacking Bikes

- Rigid & Plus Bikes

- Drop-bar & Gravel

- Full Suspension

Rigs & Roundups

- Rider & Rig

- Race/Event Rig Roundups

- Worthy Builds

- Handbuilt Bikes

- #29+ (29-plus)

- #vintage-mountain-bikes

- #cargo-bikes

- Readers' Rigs (Dispatch)

- New Bikes (Dispatch)

Plan Your Trip

- Bikepacking Guides

- Bikepacking Food

- Gear & Pack Lists

- Bike Photography

Essential Reading

- Leave No Trace (for Bikepackers)

- Guide To Bikepacking Bags

- Bikepacking Gear That Lasts

- #Bikepacking-Awards

- Power Of An Overnighter

- Advice For New Bikepackers

- Our Favorite Bikepacking Routes

-

Where to Begin

We have over 300 original and curated bikepacking routes in our global network spanning nearly 50 countries.

Start at our worldwide routes map to dig into our detailed guides with GPS maps and inspiring photography.

By Location

- The United States

- Latin America

- Middle East

By Length (days)

- Overnighters & S24O

- Weekend Routes (2-4)

- Week-long Routes (5-10)

- Odyssey Routes (11-30)

- "Freakouts" (31+)

Local Overnighters

The Local Overnighters Project is a unified effort to document and map one-night bikepacking routes all over the world—by locals, in their own backyards.

The Bikepacking Journal is our biannual printed publication. Each issue features a collection of inspiring writing and beautiful photography. Find details on the three most recent issues below, join the Bikepacking Collective to get it in the mail (anywhere in the world), or click here to find a collection of selected stories in digital format.

The special edition 10th issue of The Bikepacking Journal is one you won’t want to miss! It features 25% more pages with extra stories, bonus art and maps, and much more...

Issue 09 takes readers on trips through time—one to the early days of bicycles—and offers several reminders to be grateful for supportive friends and family, and strangers we meet along the way...

For Issue 08, we invited several contributors to return and pick up where earlier trips and ideas left off and also feature a handful of first-timers whose perspectives we’ve long been eager to share...

Reader’s Rig: Nick’s 1991 Trek 970 Singletrack

Previous Dispatch From Thu Mar 28, 2019

Registration Open for 2019 Bikepacking Summit

This week on Reader’s Rig, we scope out Nick Karwoski’s 1991 Trek 970 Singletrack, built up for trips around town from mostly repurposed parts. Find more photos and build details here…

My name is Nick Karwoski and I’m originally from Wisconsin but now live in Austin, Texas. I’m a recovered roadie who discovered touring first, then bikepacking. I try to get out on trips as much as my life allows, but end up commuting a lot more than touring.

I’d been interested in building up a a Trek 970 for a while and recently found a nice 970 XL frame at the right price, so it was time to take the plunge. My bike is a 22” 1991 Trek 970 Singletrack, mostly used for commuting, around town trips, and #coffeoutsideatx.

I salvaged a lot of the parts from a bike Co-op in Austin, used what I had lying around, and bought a few items on eBay. The bars are 1” Nitto Bullmoose attached to a Shimano STX 1 ⅛” headset with an adapter (I’m still alive). The bar tape is Serfas with .12 gauge shotgun shells for bar ends. The brake levers are Shimano Altus. The shifters are SunTour Power Thumb friction shifters. I used a Shimano Deore XT (M730) triple crankset with 9-speed XTR front (M953) and rear derailleurs (M952 Long cage). The wheels are Matrix rims, mystery hubs, a 7-speed cassette, and Compass Rat Trap Pass tires. The brakes are Tektro CR720s. The seatpost is a Velo Orange attached to a Fyxation Pilot saddle. I drilled out the fork crown hole (a tiny bit) to attach a Nitto M12 rack. The bag is a large Fabio’s Chest (the chest is the best!).

- Frame/Fork 22” 1991 Trek 970 Singletrack

- Rims Matrix 26″

- Hubs Unknown, the name has worn off!

- Tires Compass Rat Trap Pass

- Handlebar Nitto Bullmoose

- Crankset Mystery 7 speed cassette

- Cassette Shimano XT 11-46

- Derailleur(s) 9-speed SHimano XTR M953 (front) and Shimano M952 long cage (rear)

- Brakes Tektro CR720

- Shifter(s) SunTour Power Thumb friction shifters

- Saddle Fyxation Pilot

- Front Rack Nitto M12

- Front Bag(s) Swift Industries / Ultra Romance Fabio’s Chest

This bike really wants to you to stand up and mash on the pedals, just like the bikes you rode as a kid. All in all, this build was relatively inexpensive and fun to put together, and almost everything was reused. You can find it (and me) on #coffeeoutsideatx leisure rides in the ATX area.

You can follow Nick on Instagram at @bicycleexplorersclub .

FILED IN (CATEGORIES & TAGS)

Reader's rig.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.

Rad Companies that Support Bikepacking

You need to be logged in to use these features. Click here to login , or start an account if you’re not yet a member of the Bikepacking Collective…

Expecting a paywall?

Not our style, and not everyone can afford to pay for content right now. That is why we keep the majority of our routes, reviews, and reports open for everyone to enjoy. But, if you can, there are three good reasons to support us: 1. We’re independent and not funded by a multi-million-dollar corporation; 2. Our quality reporting and up-to-the-minute news is authentic, unbiased, and presented in an ad-lite browsing experience; 3. A membership costs less than a coffee per month, helps support all the content on the site, and gets you The Bikepacking Journal twice per year.

Already a member? We’re grateful for your support. Login to hide this message *Join by April 17th and start your membership with Issue 12 of The Bikepacking Journal

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

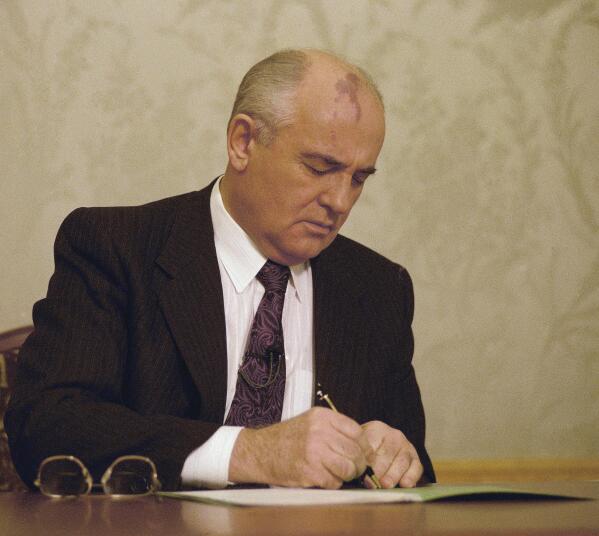

Dignified but bitter farewell to the Soviet Union – archive, 1991

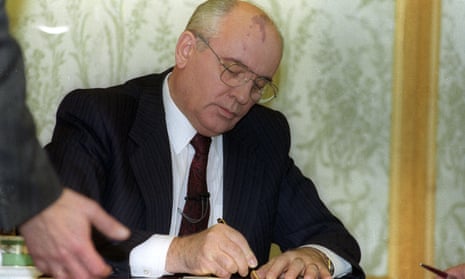

27 December 1991 : Mikhail Gorbachev resigns as Soviet president, and the USSR ceases to exist

President Gorbachev’s extraordinary six-year rule and the country over which he presided came to an end with a whimper.

When the moment came for the Soviet leader to sign himself and the USSR into history on Christmas Day, his pen ran out. He had to borrow one from an American television interviewer to sign the decree that passed control over the Soviet Union’s nuclear arsenal to Boris Yeltsin. Then he gave a brief interview to the cameras, stood up and walked out of the Kremlin.

There was bitterness in his departure. He looked exhausted and drained on Wednesday when he made his broadcast to the nation announcing his resignation, just before signing the decree. But he spoke with dignity and courage, listing the achievements of perestroika and once more bemoaning the disintegration of the union he believed in so profoundly, almost alone.

Characteristically, too, he fought on almost to the end, trying to preserve the union and his own position. He sent signals to the military, hoping the last all-union institution would back him in action against what he saw as an unconstitutional seizure of power by Boris Yeltsin and his colleagues in Ukraine and Byelorussia .

According to diplomatic sources, the presidents of those two republics, Leonid Kravchuk and Stanislav Shushkevich , avoided coming to Moscow in case they were arrested.

But Mr Gorbachev’s position was fatally weakened by the republics’ refusal to fund his government.

He tried playing the Central Asia card, knowing he had a strong pro-union ally in Nursultan Nazarbayev , the president of Kazakhstan, and that the other Central Asian leaders preferred him to Mr Yeltsin. But Mr Nazarbayev, though angry at not being invited to the first Slav meeting in Brest to set up the Commonwealth of Independent States, felt which way the wind was blowing.

So power slipped inexorably from Mr Gorbachev’s grasp, and he was left only with a humiliating shell of office from which he had no choice but to depart.

But Mr Gorbachev was not changing his views. It was, he told the nation, a matter of moral principle. ‘I have firmly supported the independence of peoples and the sovereignty of republics. But at the same time I am for the preservation of the union state … The most dangerous thing about this crisis is the collapse of statehood,’ he declared. ‘I am concerned that the people of this country have ceased to be citizens of a great power.’

Nationalism was always his blind spot. He just could not understand it. But loyalty triumphed to the country he surely still considers himself a citizen of. He did not believe in the commonwealth, he said, but now that the decision to set it up had been taken by the 11 presidents in Alma Ata last Saturday, ‘I will do everything I can to ensure that the agreements signed there lead to real concord in society.’

He admitted he had made mistakes in carrying out perestroika and glasnost, and he knew how many people felt about him, but he had no regrets. It was always a risky business launching reforms on this scale, he said, ‘but even today I’m convinced that the democratic reform we launched in the spring of 1985 was historically correct.’

Finally, he appealed to the nation ‘to preserve the democratic achievements won during the past few years. They were acquired through much suffering and tragedy. They are not to be abandoned, whatever the circumstances or pretexts.’

Unloved and unappreciated by the overwhelming majority of former Soviet citizens, Mr Gorbachev nonetheless received many moving tributes from admirers and former colleagues for his historic role.

Ukraine challenges Yeltsin

By John Rettie in Moscow 27 December 1991

The spectre of discord was growing between two key republics of the former Soviet Union yesterday as if in answer to the grim warnings of the departed President Gorbachev.

As the world hastened to recognise the main members of the new Commonwealth of Independent States within a day of the Russian tricolour replacing the Red Flag over the Kremlin, there were vehement protests from Ukraine against Russia making itself ‘the legal inheritor of the Soviet Union’.

The Ukrainian president, Leonid Kravchuk, declared uncompromisingly: ‘There is no centre in Moscow.’

Despite its agreement that Russia should have the Soviet seat on the UN security council, and that the finger of the Russian president, Boris Yeltsin, should be on the nuclear button – albeit under a system of consultation with the other nuclear republics – Ukraine is deeply dismayed by what it sees as Russian dominance of the 11-member commonwealth. Continue reading.

- From the Guardian archive

- Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Gorbachev funeral held in Moscow as Putin too busy to attend

Putin to snub Gorbachev funeral due to work schedule

Mikhail Gorbachev obituary

Kremlin fails to say whether Gorbachev will get state funeral

From Simpsons to Spitting Image: Gorbachev the pop culture icon

Mikhail Gorbachev: a divisive figure loved abroad but loathed at home

Gorbachev and Reagan: the capitalist and communist who helped end the cold war

How Gorbachev’s political legacy was destroyed by Putin

Mikhail Gorbachev: I should have abandoned the Communist party earlier

Comments (…), most viewed.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Moscow, a Newspaper City

By David Remnick

At his dacha in the woods outside Moscow, Mikhail Gorbachev climbed into the back seat of a Zil limousine and headed north, toward the Kremlin. It was the morning after Christmas, and suddenly the Soviet Union was a half-remembered dream and its last general secretary a pensioner. Gorbachev wanted to take care of some final meetings and clean out his desk before starting a few weeks of vacation. The Russian government had promised him a peaceful day or two before it took up residence in the Kremlin. But when he arrived at his office he saw that his nameplate had already been pried off the wall. “Yeltsin, Boris Nikolaevich” was there, gleaming brassily, in its place. Inside the office, Yeltsin was sitting behind the desk. For days, there had been an air of self-pity about Gorbachev, and this petty incident seemed to transform it into fury. Never mind Gorbachev’s own assaults on Yeltsin over the years. “For me, they have poisoned the air,” he complained to a reporter. “They have humiliated me.”

This was a historic moment in Moscow: for the first time, an elected President occupying the Kremlin; the hammer and sickle gone from the flagpole; the regime and the empire dissolved. And yet history felt like nothing more than a miserable winter day; the Western press corps roamed Red Square in search of passion or comment. “You care, we don’t,” an old woman from the provincial city of Tver told a clutch of reporters. With that, she stormed off in search of potatoes and milk for her family.

In the afternoon, Gorbachev’s press secretary, Andrei Grachev, invited a small group of aides, foreign reporters, and Russian editors to a reception at the Oktyabrskaya Hotel. A farewell party, Grachev called it, and he could not have chosen a more appropriate stage. For years, the hotel, across the street from the French Embassy, was a symbol of the Communist Party’s kitschy opulence. The lobby and the dining rooms are heavy on marble and mirrors. Every fixture, it seems, was designed with a certain solicitude for the aging members of the Central Committee—feudal lords of the provinces—who would visit Moscow a few times a year for their plenary sessions and shopping sprees. The Communist Party discovered in its dying days that its financial situation had declined dramatically, and that the only solution was the quick sale of its assets. The Oktyabrskaya Hotel, once known to Muscovites as the Waldorf-Astoria of the Central Committee, is now open for the high-end tourist trade.

At a few minutes before five o’clock, the reporters and the editors stood waiting at the top of the marble stairs for Gorbachev to arrive. By chance, I took my place near two of the city’s best-known newspaper editors: Len Karpinsky, the editor-in-chief and a columnist of the weekly Moscow News ; and Vitaly Tretyakov, a young defector from Moscow News , who had started Nezavisimaya Gazeta ( Independent Newspaper ), the closest thing Russia has ever had to a Western daily. Standing there, I was struck by the fact that Gorbachev’s resignation meant a transition from Karpinsky’s generation of intellectual idealists to a breed of younger men and women like Tretyakov—business neophytes, scholars, hustlers, newspaper editors—who would build a new world not so much out of the jagged ruins of the old experiment as out of fragmentary notions gathered from the West.

Karpinsky is what Muscovites call a shestidesyatnik —someone who came of age in the early nineteen-sixties, during the exhilarating thaw under Nikita Khrushchev, and grew disillusioned when Soviet tanks crushed the Prague Spring, in 1968. That generation harbored the dream of a humane socialism in Russia. Its members did not dare take the risks of full-blown dissidence but found a measure of independence and sanity in their work. There were scholars who fled the oppressive scrutiny of Moscow for institutes in provincial cities from Tartu to Novosibirsk; there were journalists who fled Pravda for Prague and wrote for Problems of Peace and Socialism . Some shestidesyatniki even found it possible to work and think in small, relatively liberal pockets of the Communist Party apparatus in Moscow. Karpinsky first met Gorbachev thirty years ago, when both were prominent in the Komsomol, the Young Communist League. Shared hints of dissatisfaction, of irony, made them comrades of a sort. But Karpinsky was both ambitious and angry, and he had long since veered into the dangerous terrain of what he always called “my life as a half-dissident.” Gorbachev’s appearance as a leader of reform, in 1985, was what Karpinsky had been waiting for all his adult life. Under Gorbachev, Karpinsky went from disgrace to rehabilitation, then on to real stardom in the new world of journalism. When Gorbachev, in the last months of his rule, made serious miscalculations and proved unable to act decisively against the hard-liners who eventually placed him under house arrest for three days in the Crimea, Karpinsky quit the Party and put his hopes in Yeltsin. Yet that conversion, after the assault on Lithuania, in January of 1991—a conversion nearly unanimous among the Moscow intellectuals of Karpinsky’s age and background—was a kind of afterword, a coda to the failed dream of perestroika . Now, as Gorbachev was leaving center stage, so was Karpinsky. Moscow News , which had broken one taboo after another in the first years of perestroika , had become a tired paper: still interesting at times, still honest, but one that spoke to a generation that now seemed, with Gorbachev, exhausted.

“It’s good that Gorbachev’s leaving now, but I am moved to the core,” Karpinsky told me. “How can I deny that I have just finished the most important chapter of my life?”

That day in Moscow, Vitaly Tretyakov was thirty-nine years old—a quarter of a century younger than Karpinsky. In just one year, Tretyakov had developed a paper totally alien to what had been the Soviet Union. From its first issue, in December of 1990, Nezavisimaya Gazeta had never known government interference or censorship, and its language was free of ideology. The first issue appeared just as Eduard Shevardnadze resigned as Foreign Minister and made his uncanny prediction of an incipient dictatorship. The paper’s coverage of the rise of the hard-line counter-revolution and the August coup was unmatched. Nezavisimaya Gazeta ’s combination of news, conflicting commentaries, highbrow essays, and satire made Moscow News seem hopelessly earnest and a little antique. While the pages of Moscow News were filled with the avuncular columns and the hand-wringing of old and worn-out men, reporters in their twenties at Nezavisimaya Gazeta were filching Party documents, printing the confessions of military spies, and conducting irreverent interviews with government leaders. Tretyakov gave free rein to people like Tatyana Malkina, who is twenty-four years old and once worked as a researcher at Moscow News . At a news conference held by the eight conspirators during the August coup, Malkina asked the most penetrating question of the hour. Fixing her eyes on the half-drunk pretender to power, Gennadi Yanayev, she said, “Tell me, please, do you realize that you have carried out a state coup? And which comparison would you find more appropriate—1917 or 1964?” Yanayev’s hand began to quiver uncontrollably as he careered through his reply.

“I’m supposed to be young, but sometimes I feel a hundred years old when I watch what my reporters dare to do,” Tretyakov told me later. “They are the first generation that knows no fear. Journalism is not a mission for them, as it was for us at Moscow News . It’s a terrific game.”

It was now five o’clock, and everyone at the top of the stairs was looking down, to see if Gorbachev would appear. Then the front doors opened and a few of Gorbachev’s closest advisers walked through—owlish little men in mouse-gray overcoats, among them Aleksandr Yakovlev, Georgi Shakhnazarov, and Anatoly Chernyaev. These were the bookish apparatchiks who had warned Gorbachev of the enemies in their midst, and had failed, ultimately, to penetrate their man’s gigantic, and tragic, self-possession. Just behind them was Gorbachev, wearing a coat the color of smoke. He looked up at the crowd and seemed embarrassed; there was something feeble in his smile. For years, he had played the press corps so easily. At first, it was enough that he was ambulatory and reasonably fluent in his own language—that he was not Brezhnev or Chernenko—but with time it was clear as well that he had an apparently effortless ability to connect, to seem to recognize a face in a crowd. And he had the gifts of surprise and agility. Now, at the end, if he was going to remain a force in politics and become Yeltsin’s moderate opposition he would want to give a decent performance at this reception. As Gorbachev shed his coat and began climbing the stairs, the reporters and the photographers began applauding; the applause was hesitant at first, but then it grew louder, and the sound reverberated from the marble and the high windows. Gorbachev clasped his hands together and shook them, more relieved than triumphant.

In a reception room, near tables covered with huge platters of smoked fish and roasted meats, Gorbachev gave a wheezy little speech, made all the worse by a horrendous public-address system. His clichés about the great missions of the past few years came out like the muffled, echoing announcements at a bowling alley. His aides looked bored and weary. But then, with that ritual over, Gorbachev threw himself into the event with gusto. He polished off a shot of lemon vodka and a slice of pickled herring, dangling the herring between forefinger and thumb and dropping it onto his tongue. In a voice of tricked-up cheer, he held his glass up to the guests and the cameras and said, “You think I can’t do it, but now I can afford to.” As Gorbachev worked the room, moving from one cluster of questioners to another, he made it clear that he had no intention of fading away. “I have big plans,” he said. “I am not leaving the political scene.” The later it got, the more pointed his gibes about his successors became. “I just could not go on,” he said. “Everything I did in the last few months, Yeltsin was always opposing. There was just no way. No way. It’s easy to be against Gorbachev, always against Gorbachev all the time. They have always been in opposition. So now I’m gone. There’s no one for them to oppose. So now let them do what they can.”

The transition in Russia these past few months has been far more profound than the turn from Gorbachev to Yeltsin. Genuine democracy is only now in the making, and economic reform remains a distant hope. So far, the great change in Russia has been one of mind and attitude.

The regime knew that it could not modernize without entering the age of information. And it was information—the truth about Soviet history and the failure of ideology—that brought an end to the regime. In the first years of perestroika , the intellectual, spiritual, and journalistic leaders of that change of mind were the shestidesyatniki —men and women like Karpinsky, idealists who suddenly provided an open, civil discourse where there had been none. In the past year, these people have given way to the new generation, less encumbered by the past or by self-doubt, more hardheaded, cynical, practical. Its members are businessmen who travel to Europe for weekend meetings; young academics specializing in the works of Hayek, Mill, and Burke; journalists who find their models in American investigative reporters and, not infrequently, the New York Post . The transition in journalism from Moscow News to Nezavisimaya Gazeta was perhaps the quickest and most visible of these shifts. To witness Len Karpinsky’s transformations—in print and in person—over the Party, socialism, and Gorbachev, and then to confront an army of kids, untroubled by the murk of ideology or by the censor’s pen, was to get a sense of the transition of Russian generations which is now in play.

Len Karpinsky’s parents were Old Bolsheviks. He was named in honor of his father’s mentor and friend Lenin. “ ‘Len’ was pretty common then, and so was ‘Ninel’—‘Lenin’ backward—or ‘Vladilen,’ for Vladimir Ilyich Lenin,” Karpinsky told me at his office one afternoon. “I’m just glad I didn’t get a name like ‘Elektrifikatsiya’ or some others my friends were stuck with.”

Karpinsky’s father, Vyacheslav Karpinsky, belonged to a generation of revolutionary romantics, the fin-de-siècle Communists. He joined the Communist Party in 1898, and in 1903, after his activities as a political organizer got him into trouble with the police in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov, he went into foreign exile, according to an interview that was published in “Voices of Glasnost,” by Stephen F. Cohen and Katrina vanden Heuvel. In Switzerland, he became Lenin’s aide and copy editor. In Moscow, after the revolution, he helped Lenin assemble his personal archives and held various posts at Pravda and the Central Committee’s Department of Propaganda. He received three Orders of Lenin, and in 1962 became the first journalist ever named a Hero of Socialist Labor.

For the Karpinsky family, a life in revolution provided an elevated existence. From 1932 to 1952, they lived in the famous House on the Embankment—a huge pile across the river from the Kremlin. Other tenants were the Kremlin élite: generals, Central Committee members, agents of the secret police. There were special dining halls stocked with groceries of a sort unknown to the rest of the socialist paradise. There were billiard halls, swimming pools, and, for the children, Special School No. 19. When Len Karpinsky was a boy, he was friendly with a couple of Stalin’s nephews. At a birthday party once, Stalin appeared in a doorway. “Children!” one of the adults announced. “Joseph Vissarionovich is here!” Stalin waved and smiled. The children all waited in silence until he left, and then resumed their games.

That was in 1935. In the coming years, Karpinsky watched dumbstruck as one after another of his friends in the building lost parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents to Stalin’s purges. Nearly every night, secret-police vans would arrive and there would be arrests—an admiral, a lecturer on Marxism-Leninism, the sisters of a spy in a foreign embassy. “There was a knock and then they disappeared,” Karpinsky said. It had been the world of Yuri Trifonov’s novella “The House on the Embankment”—a world where “a life went on that was utterly different” from the life of ordinary people. Now it was a world where the most devoted revolutionaries, the most obsequious ministers, suddenly found themselves declared “plotters” and “infiltrators” and “enemies of the people.” Karpinsky’s family was, by the standards of the building, not hard hit. One of his aunts and her two brothers were sent off to the camps. To this day, Karpinsky does not quite understand why his father, the very sort of Lenin loyalist who so threatened Stalin, was not arrested and executed. The only reason he can think of now, he says, is that by 1937 or 1938 his father was semi-retired and out of politics.

From the moment I moved to Moscow, in January of 1988, until leaving, four years later, I read Moscow News , and particularly Karpinsky, avidly. Everyone did. The leadership had installed Karpinsky’s old friend Yegor Yakovlev as editor-in-chief of the newspaper in 1986, and almost from that point it was clear that Moscow News would be the paper of the thaw generation, the one that would subtly break the taboos formed over seventy years. From time to time, I visited Karpinsky at the Moscow News office, on Pushkin Square, and he always seemed to me an honest man, if a limited writer—a representative figure, whose life had been, as he remarked to me, “an inner conflict between the ambition to be a boss in the Communist Party and the almost involuntary development of a conscience.” His appearance today, waxen and drawn, speaks of that struggle. His face is long, lined, and worn. The fingers of his right hand are yellowed up to the first knuckle, from tobacco. More often than not, when I called and asked how he was he would say dryly, “My health is awful. I’m spending the week in a sanatorium. I may die.”

Karpinsky is so unassuming, and so ironic about his own failures and hesitations, that it is hard to believe he was once an ambitious Communist, a dutiful apparatchik who believed deeply in Communism and in himself—in his entitlement to success. After entering Moscow State University, in 1947, he began working as a “propaganda man” at factories and construction sites during the days before the Party’s single-candidate elections. “My assignment was to make the workers get up at 6 a.m. and go to the polls,” he told me one afternoon. “There was a competition among the propaganda men over whose group would be the first to finish voting. The deadline was midday, by which time the whole Soviet people was supposed to have voted. That was a decision of the Party. We eighteen-year-olds were supposed to carry on propaganda among the workers, and our only tool was the promise to improve their housing conditions. They lived in horrible slums, or in railway cars, with no toilets, no heat. I loved the work, thought it was a great service—and, yes, a stepping stone. At the university, Yuri Levada, who is now a well-known sociologist, wrote an article about me called ‘The Careerist.’ And it was true. I did it all with the idea of getting to the top. That was what it was all about—to be one of the bosses.”

After a pause, Karpinsky ground out a cigarette and went on, “But, having said that, I have to say a few words in self-defense. Society during the Stalin era left open no real opportunities for self-realization or self-expression except within this perverted system of the Communist Party. The system destroyed all the other channels—the artist’s canvas, the farmer’s land. All that was left was the gigantic hierarchic system of the Party, wide at the base and growing narrower as one climbed to the top. You had to have a Party membership just for admission. That was your only opportunity. When you are engaged in that work, you forget about the social and political implications and just do it. Gradually, though, this sort of life bifurcates your mind, your intellect. You do eventually begin to understand that life is life and it’s better to do something good for thy neighbor than to climb upward stepping on his bones. It all depends on moral principles. I suppose my first doubts came when I went to Moscow State University. A Jewish friend of mine named Karl Kantor was attacked by the university’s Party committee at the beginning of Stalin’s anti-Jewish campaign. That was just the start of a long transformation.

“After graduation, I was sent to the city of Gorki for Komsomol work. At that point, Stalin had one more year to live. I got to know the working class and the peasants in Gorki. I saw the utter degradation, the ruin. I saw Soviet society as it had really emerged. Some people still think, erroneously, that the life of the apparatchik breeds only conformists and subjects loyal to the regime. Actually, the regime splits people into two opposing factions—those who believe they can make it only through conformism and timeserving, and those who, thanks to a different structure of mind, dare to question the surrounding reality.”

He paused again, and then said, “So when Stalin died I realized perfectly well what he had been all about. Still, I went to the funeral in Moscow, out of curiosity. I felt like one of those prisoners in the camps who threw their hats in the air and cried, ‘The man-eater has finally kicked the bucket!’ My father’s reaction to Stalin’s death was interesting. By then, he was retired, working for the Central Committee only as a consultant. He sat there in his office, typing on an old Underwood, which he had brought from the offices he shared with Lenin in Switzerland. He called me into his study and said, ‘Son, Comrade Stalin has passed away. And, having been an epigone of Lenin, he created all the necessary conditions for our cause to triumph.’ It was so strange. My father had never before in his life talked so formally to me. I think he talked that way because his generation had always carried the burden of promoting the Party line at all times, and he felt that it was his duty to pass that down to his children. But this was a man, eighty years old, who had conceived his idea of the Party before the revolution and while living in exile. He had to convince not me but himself. He was talking to himself.”

When Karpinsky returned from Gorki to Moscow for good, in 1959, Khrushchev was the general secretary, and the thaw was in full swing. Novy Mir , Aleksandr Tvardovsky’s monthly journal of literature and opinion, was publishing texts critical of the old regime. Khrushchev himself read Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,” and sanctioned its publication in Novy Mir . Karpinsky’s friends Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky were winning a following with their foppish lyrics and performances. In various pockets of the Central Committee apparatus, young apparatchiks wrote proposals and outlines of economic and political reform—though all within certain boundaries of ideology and language. Karpinsky, for his part, worked as the head of the Komsomol’s Department of Propaganda and Agitation and as the editor of Molodoi Kommunist ( Young Communist ). Then, in 1962, he joined the empyrean of the adult Communist world. He was promoted to Pravda ’s editorial board, to head the department of Marxism-Leninism. He had made it.

“Once I was back in Moscow from Gorki, my critical approach weakened somewhat,” Karpinsky said. “I was part of the élite again, and not merely as my father’s son but as a real member. I was part of the top nomenklatura , and the nomenklatura is another planet. It’s Mars. It’s not simply a matter of good cars or apartments. It’s the continuous satisfaction of your own exclusivity; it’s the way an army of bootlickers allows you to work for hours. All the little apparatchiks are ready to do everything for you. Your every wish is fulfilled. You can go to the theatre on a whim, you can fly to Japan from your hunting lodge. It’s a life in which everything flows easily. No, you don’t own a yacht or spend your vacations on the Côte d’Azur, but you are at the Black Sea, and that is really something. The issue is your relative well-being. You are like a king: just point your finger and it is done.”

Karpinsky’s potential as a man of the Communist Party élite was unlimited. It is conceivable that he could have won eventual appointment to the Politburo. He was a Soviet Ivy Leaguer: bright, ambitious, a Legacy. One afternoon, at a Kremlin ceremony, two of Khrushchev’s most powerful partners in the leadership, Mikhail Suslov and Boris Ponomarev, called Karpinsky their golden boy, their comer. One of them said that Karpinsky was like “a son of the regiment” to them, and that they saw for him a great future in the ideological department of the Communist Party. “We are pinning our hopes on you,” Suslov said.

Working in that rarefied atmosphere, Karpinsky got to know nearly every figure who would make a difference (one way or the other) during perestroika . He was friendly with Yegor Yakovlev, the Lenin biographer, who became the editor of Moscow News ; Yuri Karyakin, a Dostoyevski scholar, who was among the leading radical deputies in the Congress of People’s Deputies; Aleksandr Bovin, the gargantuan journalist who propagandized the “new thinking” in foreign policy at Izvestia ; the reform-minded economists Gavriil Popov and Nikolai Shmelyov and the sociologist Yevgeny Ambartsumov; Otto Latsis, the son of an Old Bolshevik and an editor at Kommunist ; Gennadi Yanayev and Boris Pugo, who helped lead the August coup; and even the leading triumvirate of reform, Eduard Shevardnadze, Aleksandr Yakovlev, and Mikhail Gorbachev.

“I first met Gorbachev when I was working at Pravda and he was in Stavropol working in the Komsomol organization there,” Karpinsky said. “He was not very well known at the time, but I must tell you that Gorbachev was saying the same things then that he said at the beginning of perestroika . He was in Moscow on some business trip or other—I forget what it was about—but we met for a couple of hours, and I was impressed. He talked about the outrage of paying combine operators by their mileage, and not by their output. To put it in a nutshell, he spoke about the absurd system of incentives, or lack of them, in the economy. He was excitable but somehow very rational. And for the first two or three years of perestroika Gorbachev was the same sort of innovator he had been when he was young. The innovative projects were always limited, within certain boundaries, and that, of course, was significant later on. Well, I understand him. Like all of us, Gorbachev had to have a dual nature. It was in his mind, in his soul. He knew well that the idea of reward for work well done was considered out of the ordinary but not quite heretical. You could experiment with something limited like that. But we were not allowed to make any political or philosophical conclusions suggesting that the system itself was a failure. In your mind, you avoided such conclusions. You were simply incapable of thinking that way. To think that way was not only career suicide but a form of despair. And so, like the rest of us, Gorbachev hedged—outwardly and within himself.”

Karpinsky and his friends were at first not much upset by Brezhnev and Suslov’s overthrow of Khrushchev, in 1964. When Karpinsky heard the news, he and Yegor Yakovlev celebrated over a bottle of cognac. Khrushchev had long since tightened restrictions on the press and the arts, and had become prone to unpredictable decisions—a manic “voluntarism,” as the Party language had it. Only years later, when Khrushchev was a sad old man living in exile at his dacha, did Karpinsky call him, to wish him well on his birthday. Karpinsky said that he was calling on behalf of “the children of the Twentieth Party Congress,” and that Khrushchev should know that one day history would make clear to everyone the importance of that session, in 1956, at which he levelled his first attacks against Stalin’s “cult of personality.”

“I have always believed this, and I am very pleased that you and your relatively young generation understand the essence of the Twentieth Congress and the policies I initiated,” Khrushchev replied. “I am so happy to hear from you in my twilight years.”

It did not take Karpinsky or anyone else long to realize that Brezhnev had no intention of making reforms. Just the opposite. A neo-Stalinist movement was in the works. One night at dinner with Yevtushenko and Otto Latsis, Karpinsky began to speak out about what was happening to his generation, to its cast of mind. “Our idea was this: when one has an education in philosophy and a certain intellectual background, one begins to understand the inner properties of reality—something I termed intellectual conscience,” he told me. “It’s not a natural, inborn conscience but a conscience that stems from a kind of thinking that links you with a moral attitude toward reality. If you understand that everything in this society is soaked in blood, that the society itself is heading toward collapse, that it is all an anti-human system—if you understand this instinctively and intellectually—then your conscience cannot remain neutral. Look, I never really took any risks, and didn’t want to. I was sort of compelled by my conscience to take what steps I did. And, once compelled to take those steps, I could never foresee the bad consequences. Every time, I thought I’d get away with it. And, every time, I didn’t.”

Karpinsky made his first real foray into the netherworld of “half-dissent” in 1967, and it was a personal disaster. He and a friend at Pravda , Fyodor Burlatsky, wrote an article in Komsomolskaya Pravda calling, in a euphemistic way, for an easing of censorship in the theatre. Karpinsky now says that the piece was “half-rotten,” especially its solipsistic arguments that the best way to eliminate anti-Soviet sentiments from the theatre would be to let the people, and not the official censors, decide. That way, the authors said, the playwrights would have no right to complain about the government, and so would be deprived of a source of anger and subject matter. But the article, “On the Road to the Première,” contained one idea, plainly stated, that caused an uproar when it appeared: the personality cult, Karpinsky and Burlatsky said, had been criticized only lightly, and the censors were preventing anything deeper.

Brezhnev, who had already begun the ideological rehabilitation of Stalin, was furious when his aides brought the piece to his attention. He took the article as a personal attack. By chance, the article had appeared on the same day that a member of the Central Committee criticized the military industry, which had been Brezhnev’s province before he became general secretary. Karpinsky, Burlatsky, and the editor of Komsomolskaya Pravda were fired. Karpinsky was quickly appointed to a job at Izvestia , but after he made a few critical remarks at a meeting of that paper’s Communist Party committee he was eased out of there, too.

Despite his inherited romantic view of Bolshevism and his own pleasure in the perquisites of power, Karpinsky could no longer hide his disaffection. The invasion of Czechoslovakia, in August of 1968, was for Karpinsky and many of his friends a breaking point. He did not join the seven young protesters who went to Red Square with banners and were arrested and sent to prison or a psychiatric hospital or into exile. Nor did he form any links with Andrei Sakharov or other leading intellectuals who had decided, once and for all, to give up their lives in the hierarchy for the dangers of political dissidence. But he did act. Under the pen name L. Okunev, Karpinsky wrote a long article called “Words Are Also Deeds,” for circulation only among a select group of friends and would-be reformers within the world of the Party and its official academies. (The article was published abroad in 1982 in Stephen F. Cohen’s book “An End to Silence.”) The pseudonym was an inside joke: “Karpinsky” derives from “carp,” and “Okunev” from “perch.” In the article Karpinsky argued that free thought—and not “rows of armed soldiers, insurgent crowds, columns of revolutionary sailors, or a volley from the cruiser Aurora”—would one day challenge the Soviet system. Furthermore, the state structures and ideological machinery would not be able to resist, for the system “lacks any serious social basis. It cannot convince anyone of its fertility and hangs on only by the instinct of self-preservation,” he wrote. “The farce of neo-Stalinism we are passing through is just the outward expression of the ‘uneasy forebodings’ the petty tyrants feel. They long for the old regime, the ‘Stalin fortress,’ but they find only decrepit foundations, too weak to support such a structure.”

The article, like nearly all of Karpinsky’s writings, is clogged with indirection and filler, great clots of the undigested verbiage of the typical Party apparatchik. It was, however, remarkable not only for its moments of clarity and daring but also for its prescience. Here was an apparatchik (“We are pinning our hopes on you,” Suslov had said) who now believed no more in the viability of the Bolshevik state than did Berdyaev, Sakharov, Amalrik, or Solzhenitsyn.

“Our tanks in Prague were, if you will, an anachronism, an ‘inadequate’ weapon,” Karpinsky wrote. “They ‘fired’ at—ideas. With no hope of hitting the target. They ‘dealt with’ the Czechoslovak situation the same way that at one time certain reptiles ‘dealt with’ the coming of the age of mammals. The reptiles bit at the air, gnashing their teeth in the same ether that was literally seething with the plankton of renewal. At the same time, fettered by their natural instincts, they searched for ‘hidden stocks of weapons’ and diligently occupied the postal and telegraph offices. With a fist to the jaw of thinking society, they thought they had knocked out and ‘captured’ its thinking processes.”

Karpinsky also provided an insider’s view, identifying within the monolith of the Party structure “a layer of Party intellectuals.” He went on to say, “To be sure, this layer is thin and disconnected; it is constantly eroded by coöptation and promotion, and is thickly interlaced with careerists, flatterers, loudmouths, jesuits, cowards, and other products of the bureaucratic selection process. But this layer could move toward an alliance with the entire social body of the intelligentsia if favorable conditions arose. This layer is already an arm of the intelligentsia, its ‘parliamentary faction’ within the administrative structure. This faction will inevitably grow, constituting a hidden opposition, without specific shape and not aware of itself, but an actually existing and widely ramified opposition at all levels within the administrative chain.”

And that is precisely what happened between 1985 and 1988. The dissidents were the bravest and most clear-minded of all, but in the early Gorbachev years they did not provide, in numbers or in force, an adequate army. As if from nowhere, intellectuals within the Party, the institutes, the press, and the literary, artistic, and scientific worlds slowly took a Soviet leader at his word that this would be a different age. For once, the purposes of a Kremlin leader and the liberal intelligentsia intersected.

The tragedy was that by the time Gorbachev came to power there were so many broken lives: great minds lost to emigration, drink, suicide, despair, or sheer cynicism. “So many people had been destroyed,” Karpinsky said. “You can maintain that split way of thinking for a while, but then you begin to degenerate and start to speak only what is permitted, and the rest of the conscience and the soul decays. Many people did not survive to perestroika . We had to create an internal moral system, and not everyone could sustain that indefinitely. Solzhenitsyn spoke about this in his essay ‘Live Not by Lies.’ I understood his viewpoint, and we tried not to live by lies, but we couldn’t always manage it. If you ignore the regulations of the state completely, and go into total dissidence, then you can’t have a family: you don’t know where you will get rent money, and your children would have to go into the streets to scrape up a living. To fulfill this principle of not living under a lie in every aspect is just impossible, because you live in a certain time.

“Compared with the people who were not afraid of prison, my friends and I were not heroes. We abstained from direct acts. This position was itself a compromise. But it was the sort of compromise you make when you are in a cage with a lion. It is understandable, though nothing to be proud of. When I myself was in the position of having to say what I felt, I said it. I just didn’t deliberately try to put my head in a noose. I used Aesopian language. I had to use hints about progress—nothing more. What we did publish only hinted at our real thoughts.”

But “Words Are Also Deeds” went far beyond Aesopian language. In 1970, Karpinsky gave a copy of his text to Roy Medvedev, the Marxist historian. A few months later, Medvedev called Karpinsky and told him that the K.G.B. had ransacked his apartment and taken every manuscript in sight, including “Words Are Also Deeds.” For a few years, Karpinsky was oblivious of the trouble he was in. He bounced around from job to job, from a sociology institute to editing Marxist-Leninist works at Progress Publishers. But in 1975, when he was caught working on the manuscript of his friend Otto Latsis’s book “On the Eve of a Great Breakthrough,” an analysis of collectivization and Stalinism, the K.G.B. called him in. Naturally, the interrogator was an old friend: a Komsomol colleague named Filipp Bobkov, who had become one of the most infamous figures in the Soviet secret police. Karpinsky tried to soften up Bobkov. “When you came to me, there was tea and cookies,” he told him. “You don’t even offer me tea. It’s not very polite.” Bobkov was not amused. He passed the damning documents along to the Communist Party Control Committee, and Len Karpinsky, the son of Lenin’s friend and the Party’s great hope, was expelled. Suslov, for one, viewed Karpinsky’s transgressions as a personal betrayal.

Now Karpinsky did whatever he could to make a living—among other things, commissioning paintings and monuments for a state agency, for which he received a minuscule salary. He kept up his friendships, talked politics, and for a while lived at the dacha he had inherited from his father. The moment of reckoning he had written about in “Words Are Also Deeds,” the advent of dissent as a cultural and political fact of life, seemed years off.

Even after Gorbachev took power, in March of 1985, Karpinsky never dreamed that change could happen so quickly. And, at first, it did not. Although the liberals in the Politburo secured the editorship of Moscow News for Karpinsky’s friend Yegor Yakovlev and told him to transform the tourist giveaway sheet into “a tribune of reform,” glasnost was initially a process of hints, insinuations. To read now through a stack of Moscow News issues from 1987 and 1988 is to get lost in a blur of non-language. The barriers were immense at first, the victories almost unbearably difficult. When the editors of Moscow News wanted to print a simple obituary of the writer Viktor Nekrasov, the Politburo itself had to give permission, and did so only after long debate.

“But still the change was tremendous,” Karpinsky said. “The difference between the thaw and glasnost was a difference in temperature. If the temperature under Khrushchev was two degrees above zero Celsius, then glasnost pushed it to twenty above. Huge chunks of ice just melted away, and now we were talking not only about Stalin’s personality cult but also about Leninism, Marxism, the essence of the system. There had been nothing like that under Khrushchev. It had been just a narrow opening, through which only Stalin’s cult could be seen. There had been no real changes. And, as we saw, it could all be reversed. The bureaucracy, the Party, the K.G.B.—all the repressive apparatus in charge of the intelligentsia and the press—were in place.”

For Karpinsky, Moscow News provided the opening to a public hearing and also to a rehabilitation. In March of 1987, he published a long article entitled “It’s Absurd to Hesitate Before an Open Door.” Like his liberal pieces of the past, it was a mixed performance. He made sure to blast the West for what he thought was its phony concern for the Soviet dissidents, but he also made a crucial point that was then getting close consideration within the government: the critique of Stalin begun in 1956 would have to go deeper. Reform without a thorough assessment of the country’s “core” problems, the rottenness of its history and foundations, would be meaningless.