The History of Transportation

Aaron Foster / Getty Images

- Invention Timelines

- Famous Inventions

- Famous Inventors

- Patents & Trademarks

- Computers & The Internet

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Whether by land or by sea, humans have always sought to traverse the earth and move to new locations. The evolution of transportation has brought us from simple canoes to space travel, and there's no telling where we could go next and how we will get there. The following is a brief history of transportation, dating from the first vehicles 900,000 years ago to modern-day times.

Early Boats

The first mode of transportation was created in the effort to traverse water: boats. Those who colonized Australia roughly 60,000–40,000 years ago have been credited as the first people to cross the sea, though there is some evidence that seafaring trips were carried out as far back as 900,000 years ago.

The earliest known boats were simple logboats, also referred to as dugouts, which were made by hollowing out a tree trunk. Evidence for these floating vehicles comes from artifacts that date back to around 10,000–7,000 years ago. The Pesse canoe—a logboat—is the oldest boat unearthed and dates as far back as 7600 BCE. Rafts have been around nearly as long, with artifacts showing them in use for at least 8,000 years.

Horses and Wheeled Vehicles

Next, came horses. While it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when humans first began domesticating them as a means of getting around and transporting goods, experts generally go by the emergence of certain human biological and cultural markers that indicate when such practices started to take place.

Based on changes in teeth records, butchering activities, shifts in settlement patterns, and historic depictions, experts believe that domestication took place around 4000 BCE. Genetic evidence from horses, including changes in musculature and cognitive function, support this.

It was also roughly around this period that the wheel was invented. Archaeological records show that the first wheeled vehicles were in use around 3500 BCE, with evidence of the existence of such contraptions found in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucuses, and Central Europe. The earliest well-dated artifact from that time period is the "Bronocice pot," a ceramic vase that depicts a four-wheeled wagon that featured two axles. It was unearthed in southern Poland.

Steam Engines

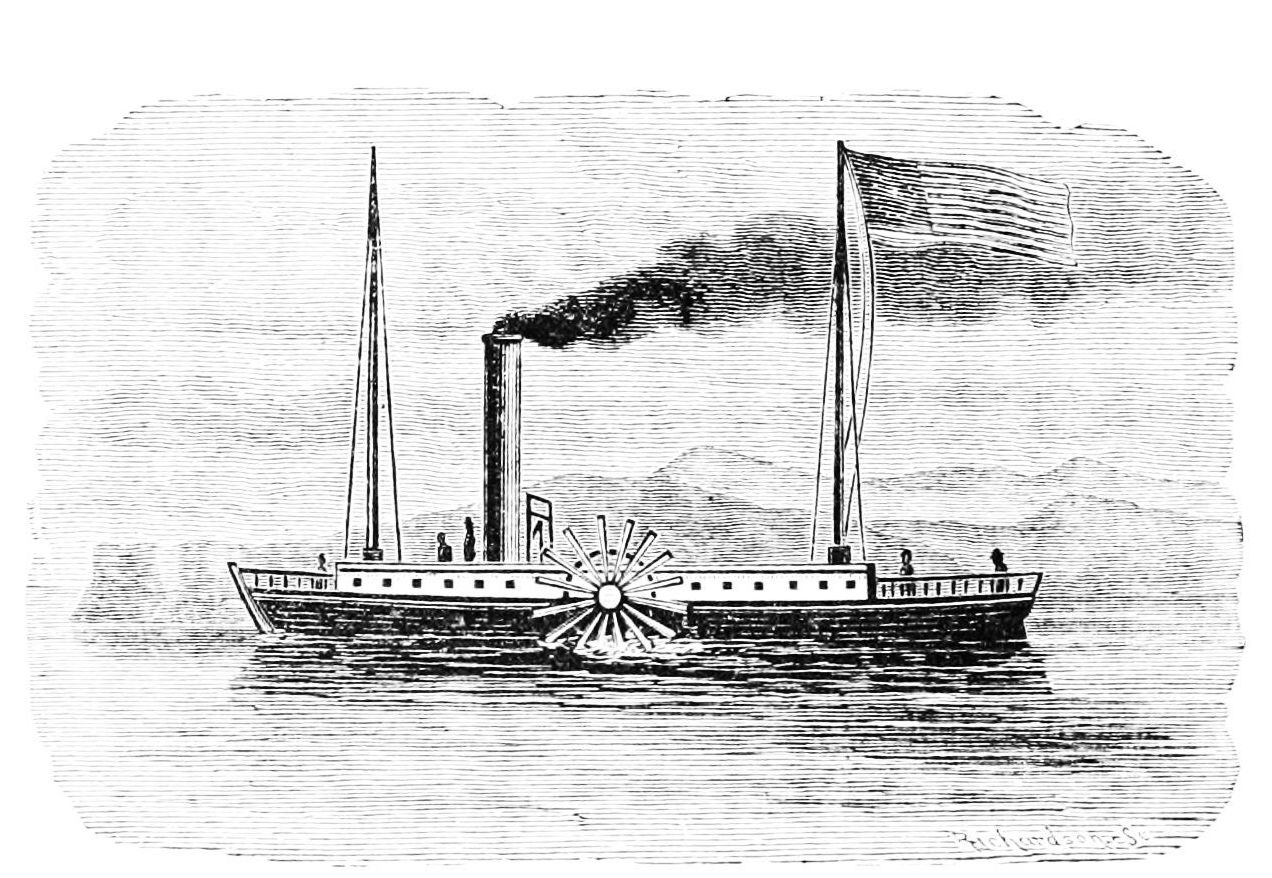

In 1769, the Watt steam engine changed everything. Boats were among the first to take advantage of steam-generated power; in 1783, a French inventor by the name of Claude de Jouffroy built the "Pyroscaphe," the world’s first steamship . But despite successfully making trips up and down the river and carrying passengers as part of a demonstration, there wasn’t enough interest to fund further development.

While other inventors tried to make steamships that were practical enough for mass transport, it was American Robert Fulton who furthered the technology to where it was commercially viable. In 1807, the Clermont completed a 150-mile trip from New York City to Albany that took 32 hours, with the average speed clocking in at about five miles per hour. Within a few years, Fulton and company would offer regular passenger and freight service between New Orleans, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi.

Back in 1769, another Frenchman named Nicolas Joseph Cugnot attempted to adapt steam engine technology to a road vehicle—the result was the invention of the first automobile . However, the heavy engine added so much weight to the vehicle that it wasn't practical. It had a top speed of 2.5 miles per hour.

Another effort to repurpose the steam engine for a different means of personal transport resulted in the "Roper Steam Velocipede." Developed in 1867, the two-wheeled steam-powered bicycle is considered by many historians to be the world’s first motorcycle .

Locomotives

One mode of land transport powered by a steam engine that did go mainstream was the locomotive. In 1801, British inventor Richard Trevithick unveiled the world’s first road locomotive—called the “Puffing Devil”—and used it to give six passengers a ride to a nearby village. It was three years later that Trevithick first demonstrated a locomotive that ran on rails, and another one that hauled 10 tons of iron to the community of Penydarren, Wales, to a small village called Abercynon.

It took a fellow Brit—a civil and mechanical engineer named George Stephenson—to turn locomotives into a form of mass transport. In 1812, Matthew Murray of Holbeck designed and built the first commercially successful steam locomotive, “The Salamanca,” and Stephenson wanted to take the technology a step further. So in 1814, Stephenson designed the "Blücher," an eight-wagon locomotive capable of hauling 30 tons of coal uphill at a speed of four miles per hour.

By 1824, Stephenson improved the efficiency of his locomotive designs to where he was commissioned by the Stockton and Darlington Railway to build the first steam locomotive to carry passengers on a public rail line, the aptly named "Locomotion No. 1." Six years later, he opened the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the first public inter-city railway line serviced by steam locomotives. His notable accomplishments also include establishing the standard for rail spacing for most of the railways in use today. No wonder he’s been hailed as " Father of Railways ."

Technically speaking, the first navigable submarine was invented in 1620 by Dutchman Cornelis Drebbel. Built for the English Royal Navy, Drebbel’s submarine could stay submerged for up to three hours and was propelled by oars. However, the submarine was never used in combat, and it wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that designs leading to practical and widely used submersible vehicles were realized.

Along the way, there were important milestones such as the launch of the hand-powered, egg-shaped "Turtle " in 1776, the first military submarine used in combat. There was also the French Navy submarine "Plongeur," the first mechanically powered submarine.

Finally, in 1888, the Spanish Navy launched the "Peral," the first electric, battery-powered submarine, which also so happened to be the first fully capable military submarine. Built by a Spanish engineer and sailor named Isaac Peral, it was equipped with a torpedo tube, two torpedoes, an air regeneration system, and the first fully reliable underwater navigation system, and it posted an underwater speed of 3.5 miles per hour.

The start of the twentieth century was truly the dawn of a new era in the history of transportation as two American brothers, Orville and Wilbur Wright, pulled off the first official powered flight in 1903. In essence, they invented the world’s first airplane. Transport via aircraft took off from there with airplanes being put into service within a few short years during World War I. In 1919, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown completed the first transatlantic flight, crossing from Canada to Ireland. The same year, passengers were able to fly internationally for the first time.

Around the same time that the Wright brothers were taking flight, French inventor Paul Cornu started developing a rotorcraft. And on November 13, 1907, his "Cornu" helicopter, made of little more than some tubing, an engine, and rotary wings, achieved a lift height of about one foot while staying airborne for about 20 seconds. With that, Cornu would lay claim to having piloted the first helicopter flight .

Spacecraft and the Space Race

It didn’t take long after air travel took off for humans to start seriously considering the possibility of going further up and toward the heavens. The Soviet Union surprised much of the western world in 1957 with its successful launch of Sputnik, the first satellite to reach outer space. Four years later, the Russians followed that by sending the first human, pilot Yuri Gagaran, into outer space aboard the Vostok 1.

These achievements would spark a “space race” between the Soviet Union and the United States that culminated in the Americans taking what was perhaps the biggest victory lap among national rivals. On July 20, 1969, the lunar module of the Apollo spacecraft, carrying astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, touched down on the surface of the moon.

The event, which was broadcast on live TV to the rest of the world, allowed millions to witness the moment Armstrong became the first man to ever step foot on the moon, a moment he heralded as “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

- The History of Railroad Technology

- The History of Steamboats

- The History of Steam-Powered Cars

- George Stephenson and the Invention of the Steam Locomotive Engine

- 19th Century Locomotive History

- Biography of Robert Fulton, Inventor of the Steamboat

- How Do Steam Engines Work?

- The Origins of the Term, 'Horsepower'

- The Railways in the Industrial Revolution

- Great Father-Son Inventor Duos

- The History of the Tom Thumb Steam Engine and Peter Cooper

- Trains Coloring Book

- A History of the Automobile

- The Most Impactful Inventions of the Last 300 Years

- The Most Important Inventions of the 19th Century

- The History of Electric Vehicles Began in 1830

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Sweepstakes

- Travel Tips

What Travel Looked Like Through the Decades

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/maya-kachroo-levine-author-pic-1-2000-1209fcfd315444719a7906644a920183.jpg)

Getting from point A to point B has not always been as easy as online booking, Global Entry , and Uber. It was a surprisingly recent event when the average American traded in the old horse-and-carriage look for a car, plane, or even private jet .

What was it like to travel at the turn of the century? If you were heading out for a trans-Atlantic trip at the very beginning of the 20th century, there was one option: boat. Travelers planning a cross-country trip had something akin to options: carriage, car (for those who could afford one), rail, or electric trolley lines — especially as people moved from rural areas to cities.

At the beginning of the 1900s, leisure travel in general was something experienced exclusively by the wealthy and elite population. In the early-to-mid-20th century, trains were steadily a popular way to get around, as were cars. The debut regional airlines welcomed their first passengers in the 1920s, but the airline business didn't see its boom until several decades later. During the '50s, a huge portion of the American population purchased a set of wheels, giving them the opportunity to hit the open road and live the American dream.

Come 1960, airports had expanded globally to provide both international and domestic flights to passengers. Air travel became a luxury industry, and a transcontinental trip soon became nothing but a short journey.

So, what's next? The leisure travel industry has quite a legacy to fulfill — fancy a trip up to Mars , anyone? Here, we've outlined how travel (and specifically, transportation) has evolved over every decade of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The 1900s was all about that horse-and-carriage travel life. Horse-drawn carriages were the most popular mode of transport, as it was before cars came onto the scene. In fact, roadways were not plentiful in the 1900s, so most travelers would follow the waterways (primarily rivers) to reach their destinations. The 1900s is the last decade before the canals, roads, and railway plans really took hold in the U.S., and as such, it represents a much slower and antiquated form of travel than the traditions we associate with the rest of the 20th century.

Cross-continental travel became more prevalent in the 1910s as ocean liners surged in popularity. In the '10s, sailing via steam ship was the only way to get to Europe. The most famous ocean liner of this decade, of course, was the Titanic. The largest ship in service at the time of its 1912 sailing, the Titanic departed Southampton, England on April 10 (for its maiden voyage) and was due to arrive in New York City on April 17. At 11:40 p.m. on the evening of April 14, it collided with an iceberg and sank beneath the North Atlantic three hours later. Still, when the Titanic was constructed, it was the largest human-made moving object on the planet and the pinnacle of '10s travel.

The roaring '20s really opened our eyes up to the romance and excitement of travel. Railroads in the U.S. were expanded in World War II, and travelers were encouraged to hop on the train to visit out-of-state resorts. It was also a decade of prosperity and economic growth, and the first time middle-class families could afford one of the most crucial travel luxuries: a car. In Europe, luxury trains were having a '20s moment coming off the design glamour of La Belle Epoque, even though high-end train travel dates back to the mid-1800s when George Pullman introduced the concept of private train cars.

Finally, ocean liners bounced back after the challenges of 1912 with such popularity that the Suez Canal had to be expanded. Most notably, travelers would cruise to destinations like Jamaica and the Bahamas.

Cue "Jet Airliner" because we've made it to the '30s, which is when planes showed up on the mainstream travel scene. While the airplane was invented in 1903 by the Wright brothers, and commercial air travel was possible in the '20s, flying was quite a cramped, turbulent experience, and reserved only for the richest members of society. Flying in the 1930s (while still only for elite, business travelers) was slightly more comfortable. Flight cabins got bigger — and seats were plush, sometimes resembling living room furniture.

In 1935, the invention of the Douglas DC-3 changed the game — it was a commercial airliner that was larger, more comfortable, and faster than anything travelers had seen previously. Use of the Douglas DC-3 was picked up by Delta, TWA, American, and United. The '30s was also the first decade that saw trans-Atlantic flights. Pan American Airways led the charge on flying passengers across the Atlantic, beginning commercial flights across the pond in 1939.

1940s & 1950s

Road trip heyday was in full swing in the '40s, as cars got better and better. From convertibles to well-made family station wagons, cars were getting bigger, higher-tech, and more luxurious. Increased comfort in the car allowed for longer road trips, so it was only fitting that the 1950s brought a major expansion in U.S. highway opportunities.

The 1950s brought the Interstate system, introduced by President Eisenhower. Prior to the origination of the "I" routes, road trippers could take only the Lincoln Highway across the country (it ran all the way from NYC to San Francisco). But the Lincoln Highway wasn't exactly a smooth ride — parts of it were unpaved — and that's one of the reasons the Interstate system came to be. President Eisenhower felt great pressure from his constituents to improve the roadways, and he obliged in the '50s, paving the way for smoother road trips and commutes.

The '60s is the Concorde plane era. Enthusiasm for supersonic flight surged in the '60s when France and Britain banded together and announced that they would attempt to make the first supersonic aircraft, which they called Concorde. The Concorde was iconic because of what it represented, forging a path into the future of aviation with supersonic capabilities. France and Britain began building a supersonic jetliner in 1962, it was presented to the public in 1967, and it took its maiden voyage in 1969. However, because of noise complaints from the public, enthusiasm for the Concorde was quickly curbed. Only 20 were made, and only 14 were used for commercial airline purposes on Air France and British Airways. While they were retired in 2003, there is still fervent interest in supersonic jets nearly 20 years later.

Amtrak incorporated in 1971 and much of this decade was spent solidifying its brand and its place within American travel. Amtrak initially serviced 43 states (and Washington D.C.) with 21 routes. In the early '70s, Amtrak established railway stations and expanded to Canada. The Amtrak was meant to dissuade car usage, especially when commuting. But it wasn't until 1975, when Amtrak introduced a fleet of Pullman-Standard Company Superliner cars, that it was regarded as a long-distance travel option. The 235 new cars — which cost $313 million — featured overnight cabins, and dining and lounge cars.

The '80s are when long-distance travel via flight unequivocally became the norm. While the '60s and '70s saw the friendly skies become mainstream, to a certain extent, there was still a portion of the population that saw it as a risk or a luxury to be a high-flyer. Jetsetting became commonplace later than you might think, but by the '80s, it was the long-haul go-to mode of transportation.

1990s & 2000s

Plans for getting hybrid vehicles on the road began to take shape in the '90s. The Toyota Prius (a gas-electric hybrid) was introduced to the streets of Japan in 1997 and took hold outside Japan in 2001. Toyota had sold 1 million Priuses around the world by 2007. The hybrid trend that we saw from '97 to '07 paved the way for the success of Teslas, chargeable BMWs, and the electric car adoption we've now seen around the world. It's been impactful not only for the road trippers but for the average American commuter.

If we're still cueing songs up here, let's go ahead and throw on "Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous," because the 2010s are when air travel became positively over-the-top. Qatar Airways rolled out their lavish Qsuites in 2017. Business class-only airlines like La Compagnie (founded in 2013) showed up on the scene. The '10s taught the luxury traveler that private jets weren't the only way to fly in exceptional style.

Of course, we can't really say what the 2020 transportation fixation will be — but the stage has certainly been set for this to be the decade of commercial space travel. With Elon Musk building an elaborate SpaceX rocket ship and making big plans to venture to Mars, and of course, the world's first space hotel set to open in 2027 , it certainly seems like commercialized space travel is where we're headed next.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Ellie-Nan-Storck-00d7064c4ef24a22a8900f0416c31833.jpeg)

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Transportation Revolution

The transportation revolution in the United States began when Americans taking advantage of features of the natural environment to move people and things from place to place began searching for ways to make transport cheaper, faster, and more efficient. Over time a series of technological changes allowed transportation to advance to the point where machines have effectively conquered distance. People can almost effortlessly travel to anywhere in the world and can inexpensively ship raw materials and products across a global market.

But this technology is not ubiquitous, and it is not necessarily democratic. As a famous science fiction writer once said, the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed. Modern transportation infrastructure is controlled to a great extent by large corporations, but the benefits of transport are depended on by everyone. And transportation technology itself requires specific conditions such as abundant, cheap, portable energy in the form of fossil fuels, and public infrastructure created by our own and foreign governments, that even those large corporations depend upon but don’t control.

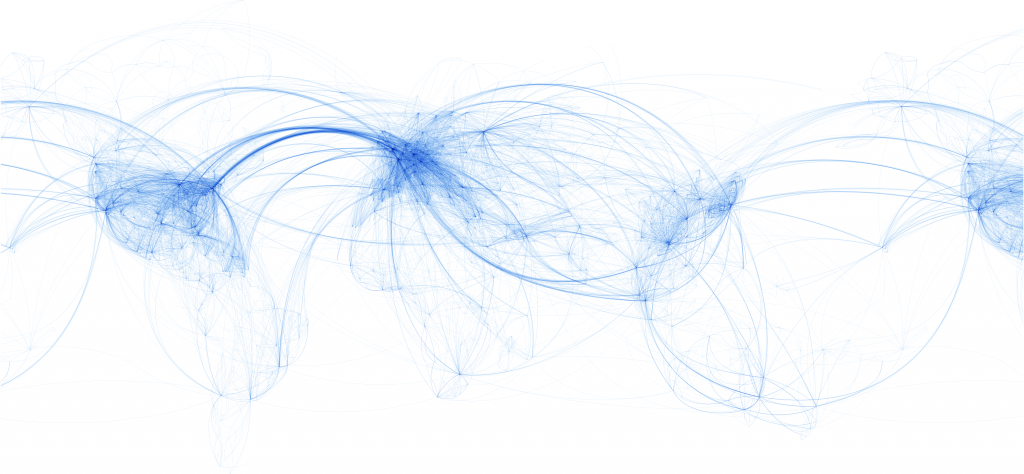

When we think of transportation, it is natural to think first about going places. Getting on a plane in one hemisphere and getting off on the other side of the world is a life-changing opportunity which was unavailable to most people as little as a generation ago, and unthinkable two generations ago. But more crucial to our daily lives than the freedom offered by world travel is the cargo from the other side of the world that reaches us quickly in the holds of jets and more slowly but in almost unimaginable volume in containers on ships. The global transportation of foods, raw materials, and finished goods goes virtually unnoticed in our daily lives, but makes our contemporary consumer lifestyle possible.

Although even the early stages of the transportation revolution allowed people like seventy-year old Achsah Ranney, from Chapter Five’s Supplement, to travel regularly between her children’s homes in Massachusetts, New York, and Michigan, the more significant change was the ability of her sons and of other Americans to move freight from place to place. The ability to effectively ship food and other goods to where they were needed allowed people to stay put, and even to concentrate themselves in cities in a way they had never been able to do before. The growth of eastern cities depended just as much on the transportation revolution as did the building of new cities in the west.

As we have already seen, early Americans made amazing journeys with very primitive methods of transportation. The people who crossed Beringia and settled North and South America were able to cover startlingly long distances on foot. European explorers crossed dangerous oceans to visit the Americas in tiny ships. Human and animal power has been used extensively throughout American history, and is still used today to reach remote areas off the grid. But it is clear that improvements in transportation technology have been among the most powerful drivers of change in our history. And the transportation revolution has certainly changed our relationship with the American environment.

Technological improvements to ocean-going ships in the fifteenth century made European colonialism possible in the first place. Ships became bigger, faster, and safer. More people and goods could leave the safety of coastal waters and cross the oceans, and the places these improved ships connected became centers of trade, population, and wealth. This pattern of growth repeated itself as new technologies were developed to help Americans expand across the continent.

As we have seen, American colonists depended on trade with England and with the sugar planters of the West Indies to make their outposts in New England and Virginia successful. But from the beginning of the American Revolution to the conclusion of the War of 1812, relations between the new nation and Britain were tense and trade suffered. If it had not found a way to ship people and goods to and from its own frontier, the United States would have remained a coastal nation focused on ports like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. The barely-remembered Whiskey Rebellion of 1791, when George Washington led United States troops against American farmers in western Pennsylvania, was really about transportation. Farmers west of the Appalachian mountains could not easily haul wagon-loads of grain to eastern markets, so they turned their harvests into a more portable product by distilling grain into whiskey. The farmers believed the government’s excise tax on distilled spirits had been instituted to drive them out of the whiskey business for the benefit of large Eastern distillers. Since they had few other sources of income, the tax was a serious issue for westerners. Luckily, the incoming Jefferson administration repealed the tax in 1801 and increasing Ohio River shipping provided new outlets for western produce.

Roads and Rivers

On the eve of the Revolution, the only road that did not hug the east coast followed the Hudson River Valley into western New York on its way to Montreal (this was one reason colonial Americans seemed continually obsessed with the idea of conquering Montreal and bringing it into the United States). Less than thirty years later, riders working for the Post Office Department carried mail to nearly all the new settlements of the interior. The postal system’s designer, Benjamin Franklin, understood that in order for the new Republic to function, information had to flow freely. Franklin set a low rate for mailing newspapers, insuring that news would circulate widely in the newly-settled areas. But it was one thing carrying saddlebags filled with letters and newspapers to the frontier, and something else moving people and freight.

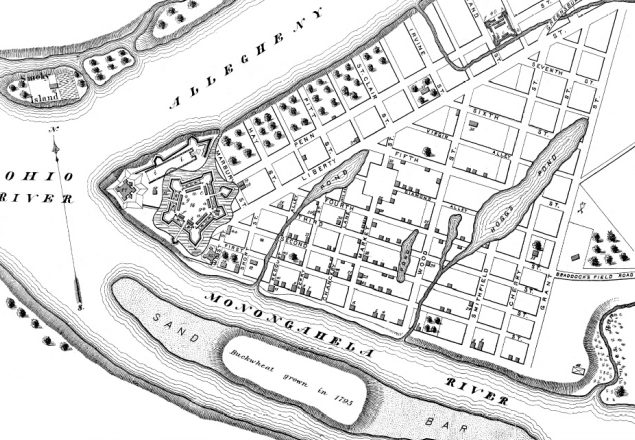

Rivers were the first important routes to the interior of North America. The Ohio River, which begins at Pittsburgh and flows southwest to join the Mississippi, helped people get to their new farms in the Ohio Valley and then helped them carry their farm produce to markets. The Ohio River Valley became one of the first areas of rapid settlement after the Revolution, along with the Mohawk River Valley in western New York. The importance of river shipping is illustrated by the fact that over fifty thousand miles of tributary rivers and streams in the Mississippi watershed were used to float goods to the port of New Orleans. The dependence of western farmers on the Spanish port also explains why New Orleans was a considered strategic city by the United States in the War of 1812. Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 purchase of the Louisiana Territory had actually begun as an attempt to buy the city of New Orleans, and Andrew Jackson’s defense of the port during the War of 1812 was vital to insuring the success of western expansion.

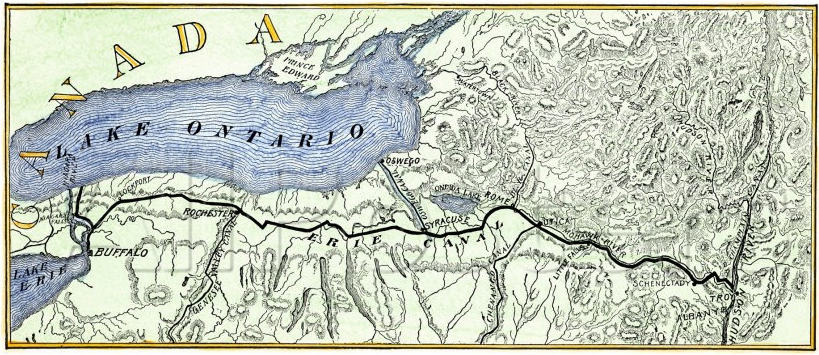

Early westward expansion depended on rivers, and towns and cities built during this era were usually on a waterway. Pittsburgh, Columbus, Cincinnati, Louisville, St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, and St. Paul all owe their locations to the river systems they provide access to. Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and Milwaukee utilize the Great Lakes in the same way. These lakeside cities exploded after the Erie Canal opened a route from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic, and allowed New York to overtake New Orleans as the nation’s most important commercial port. The 363-mile Erie Canal was so successful that another four thousand miles of canals were dug in America before the Civil War.

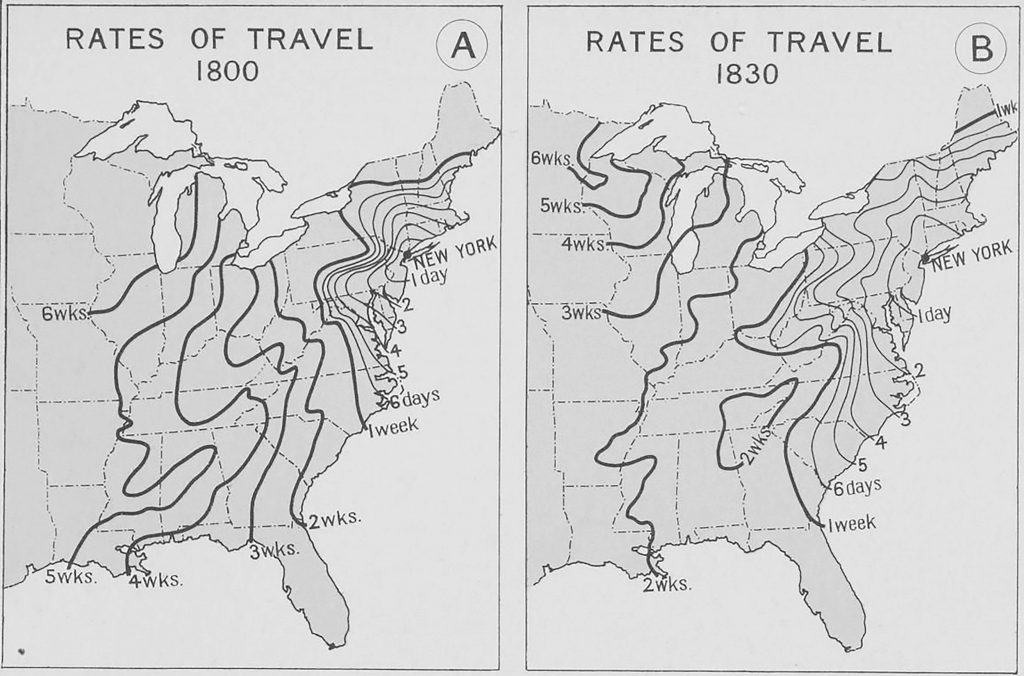

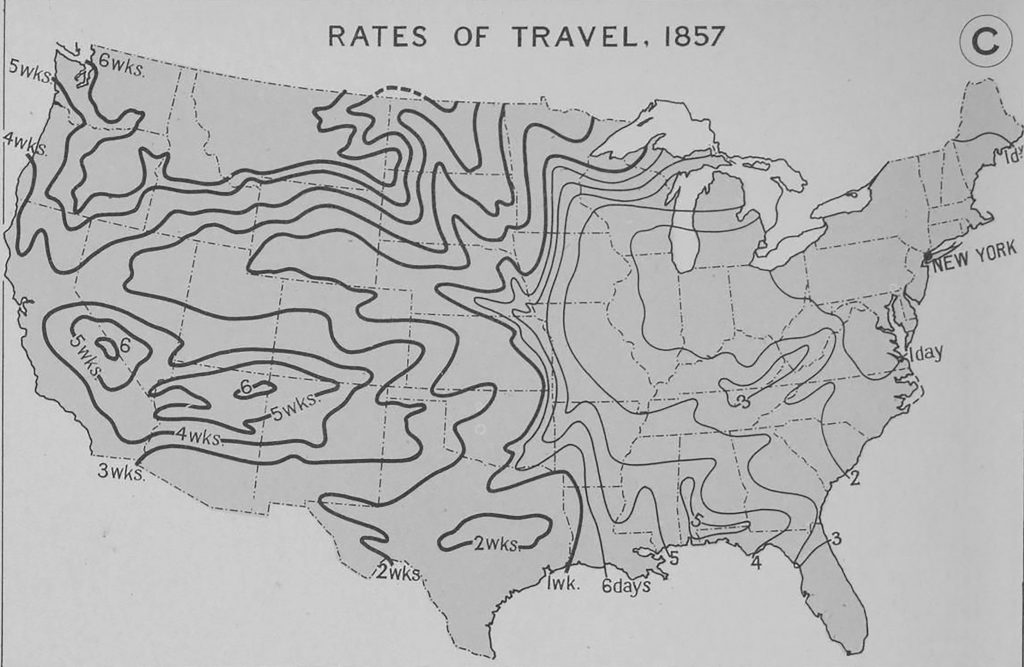

In 1800, it took nearly two weeks to reach Buffalo from New York City, a month to get to Detroit, and six grueling weeks of travel to arrive at the swampy lake-shore settlement that would become Chicago. Thirty years later, Buffalo was just five days away, Detroit about ten days, and Chicago less than three weeks. Horses pulled canal boats from towpaths on shore, eliminating the strain of travel for the boats’ passengers. Floating along on calm water was infinitely more comfortable than spending weeks on a wagon, in a cramped stage coach, or on horseback. The number of people willing to make long trips increased accordingly. And the amount of freight shipped to New York, after the canal cut shipping costs by over ninety percent, increased astronomically. Goods flowed along the Canal in both directions, offering life-changing opportunities. As mentioned previously, within ten years of the Erie Canal’s completion, the last fulling mill processing homespun cloth in Western New York shut its doors. Women no longer had to spend their time spinning wool and weaving their own textiles to make their family’s clothing. They could buy bolts of wool and cotton fabrics from the same merchant at the local general store who ground their family’s grain into flour and shipped it on the Canal to eastern cities. With fewer demands on their time, many women were able to not only improve their own quality of life, but contribute to family income by taking in piece-work, raising cash crops, or keeping cows and churning butter for sale to their local merchants.

The Age of Steam

Steam technology changed the nature of transportation. Until steam engines were put on riverboats, shipping had depended on either wind and river currents or on human and animal power. Goods could easily be floated south from farms on the nation’s rivers, but it was much more difficult and expensive to ship products against the rivers’ currents to the frontier. Flatboats and rafts accumulated at downstream ports, and were often broken down and burned as firewood. Steam engines made it possible to sail upstream as easily and nearly as quickly as down, causing an explosion of travel and shipping that radically changed frontier life.

Steam engines were a product of early European industrialism. The first steam patent was granted to a Spanish inventor named Jerónimo Beaumont in 1606, whose engine drove a pump used to drain mines. Englishman James Watt’s 1781 engine was the first to produce rotary power that could be adapted to drive mills, wheels, and propellers. Robert Fulton, an American inventor who had previously patented a canal-dredging machine, visited Paris and caught steamboat fever. Fulton sailed an experimental model on the Seine, and then returned home and launched the first commercial American steamboat on the Hudson River in 1807. The Clermont was able to sail upriver 150 miles from New York City to Albany in 32 hours. In 1811, Fulton built the New Orleans in Pittsburgh and began steamboat service on the Mississippi.

Although Robert Fulton died just a few years later of tuberculosis, his partners Nicholas Roosevelt and Robert Livingston carried on his business, and the age of riverboats was underway. Like Fulton’s prototype and the Clermont, the New Orleans was a large, heavy side-wheeler with a deep draft. It was not the most efficient design for shallow water, and it did not take long for ship-builders to settle on the familiar shallow-draft rear-paddle riverboats that carried freight on the Mississippi and its tributaries well into the 20th century. The shallower a riverboat’s draft, the farther upriver it could travel. Steam-powered riverboats soon pushed the transportation frontier to Fort Pierre in the Dakota territory and even to Fort Benton, Montana. Riverboats made it possible to ship goods in and out of nearly the whole area Thomas Jefferson had acquired in the Louisiana Purchase just a generation earlier. And steam-powered ocean shipping made the markets of Britain and Europe readily accessible to farmers and merchants in the middle of North America.

The other transportation technology enabled by steam power, of course, was the railroad. But railroads were even more revolutionary than steamboats. In spite of their power and speed, steam-powered riverboats depended on rivers or occasionally on canals to run, but a railroad could be built almost anywhere. Suddenly, the expansion of American commerce was no longer limited by the routes nature had provided into the frontier.

America’s first small railroads had actually been built on the East Coast before a steam engine was available to power them. Trains of cars were pulled by horses and looked a lot like stage-coaches on rails. But after Englishman George Stephenson’s locomotives began pulling passengers and freight in northwestern England in the mid-1820s, Americans quickly switched to steam. The first locomotive used to pull cars in the United States was the Tom Thumb, built in 1830 for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Although Tom Thumb lost its maiden race against a horse-drawn train, Baltimore and Ohio owners were convinced by the demonstration of steam technology and committed to developing steam locomotives. The railroad, which had been established in 1827 to compete with the Erie Canal, already advertised itself as a faster way to move people and freight from the interior to the coast. Adding steam engines accelerated rail’s advantage over canal and river shipping.

Over 9,000 miles of track had been laid by 1850, most of it connecting the northeast with western farmlands. The Mississippi River was still the preferred route to market from Louisville and St. Louis south. But Cincinnati and Columbus became connected by rail to the Great Lake ports at Sandusky and Cleveland, giving the northern Ohio Valley faster access to New York markets. Detroit and Lake Michigan were also connected by rail, making the long steamboat trip around the northern reach of Michigan’s lower peninsula unnecessary.

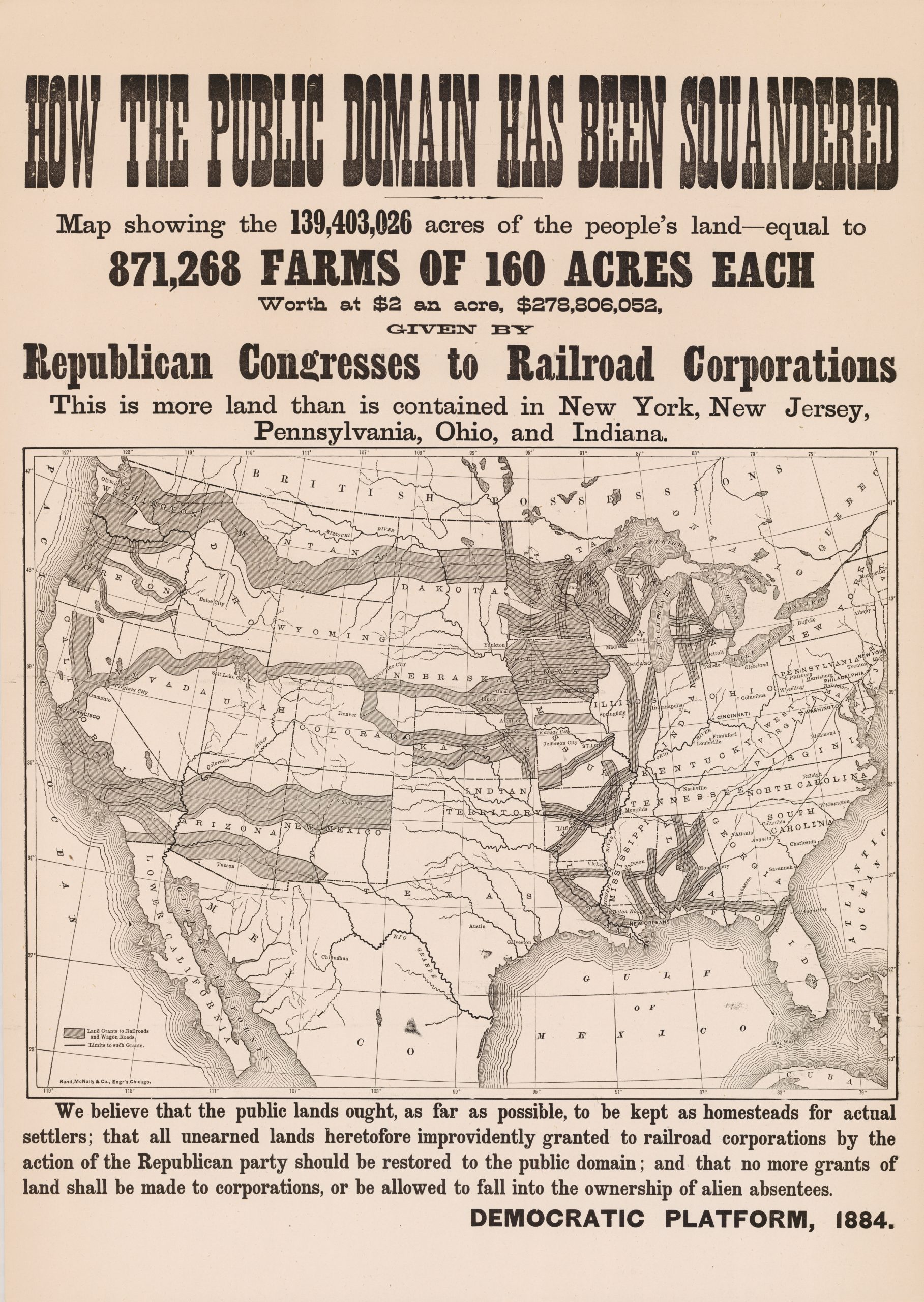

By 1857, rail travelers could reach Chicago in less than two days and could be almost anywhere in the northern Mississippi Valley in three. On the eve of the Civil War in 1860, Chicago was already becoming the railroad hub of the Midwest. The Illinois Central Company had been chartered in 1851 to build a rail line from the lead mines at Galena to Cairo, where the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers joined. Galena is also located on the Mississippi on the northern border of Illinois, but rapids north of St. Louis made transporting ore on the river impossible, illustrating the advantage of rails over rivers. A railroad line to Cairo, with a branch line to Chicago, would also attract settlers and investors to Illinois. Young Illinois attorney Abraham Lincoln helped the Illinois Central lobby legislators and receive the first federal land grant ever given to a railroad company. The company was given 2.6 million acres of land, and Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas helped design the checkerboard distribution of parcels that would become common for railroad land grants. The map below shows the extent of the land the government gave to the Illinois Central Company, which a few years later showed its gratitude by helping to finance Lincoln’s Presidential campaign against Douglas.

The North’s advantage over the Confederate South in railroad miles and the Union Army’s ability to move troops and supplies efficiently had a definite impact on the outcome of the Civil War. In the years following the war, the shattered South added very little railroad track and repaired only a small percentage of the tracks the Union Army had destroyed during the war. While railroads languished in the South, rail miles in the North exploded. In 1869, the West Coast was connected through Chicago to the Northeast, when the Union and Central Pacific Lines met at Promontory Point Utah on May 10th. The building of a transcontinental railroad was made possible by the Pacific Railroad Act, which President Lincoln had signed into law in 1862.

Public or Private?

The Pacific Railroad Act was the first law allowing the federal government to give land directly to corporations. Previously the government had granted land to the states for the benefit of corporations. The Act granted ten square miles of land to the railroad companies for every mile of track they built. Land next to railroads always increased in value. The unprecedented gift of ten square miles of rapidly-appreciating land for every mile of track was a tremendous incentive to railroad companies to lay just as much track as they possibly could. Decisions to build lines were frequently based on the land granted, rather than on whether or not railroad companies expected the new lines to carry enough traffic or generate enough freight revenue to pay for themselves. In the eighteen years between the original Illinois Central grant of 1851 and the completion of the transcontinental line in 1869, privately-owned railroads received about 175 million acres of public land at no cost. This amounts to about seven percent of the land area of the contiguous 48 states, or an area slightly larger than Texas. For comparison, the Homestead Act distributed 246 million acres to American farmers over a 72-year period between 1862 and 1934, but required homesteaders to live on and to farm the land continuously for five years or pay for their parcel. The justification for the residency requirement was that the government was concerned homesteaders would become speculators and flip their farms. Railroad land grants were made with no similar stipulations because railroad corporations were expected to sell the lands they were given at a substantial profit.

It has often been argued that a national infrastructure project as large as a transcontinental railway could never have been built without government assistance. The West Coast and western territories needed to be brought into the Union, some historians have argued, and the only way to achieve this was with government-supported railroads. Ironically, the same people who make this argument usually also claim that it would have been disastrous for the government to have owned the railroads it had made possible with its legislation, loans, and land grants. An undertaking of this scope and scale, they say, requires that corporations be given monopolies and grants of natural resources and public credit. These arguments make it seem inevitable that giant corporations taking huge gifts from the public sector were the only way for America to move forward and build a rail network. However, history shows that this was not the only way a national rail system could have been built.

There are numerous examples of rail systems built and managed by the public sector in foreign countries, especially during the nineteenth century when nearly every rail system outside the United States was state-owned and operated. However, for the sake of simplicity we will restrict the comparison to the United States. The Northern Pacific Railway, a private corporation chartered by Congress in 1864, built 6,800 miles of track to connect Lake Superior with Puget Sound. In return, the corporation was given 40 million acres of land in 50-mile checkerboards on either side of its tracks. Not only did the Northern Pacific rely on the government for land and financing, the railroad used the services of the U.S. Army to protect its surveyors and to move uncooperative Indians out of its way. When the Northern Pacific’s proposed route cut through the center of the Great Sioux Reservation, established by the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, the corporation pressured the government to break the treaty. George Custer announced that gold had been discovered in the Black Hills after an 1874 mission protecting Northern Pacific surveyors, and Washington let the treaty be disregarded by both the railroad and the prospectors. The Indians responded with the Great Sioux War of 1876, which culminated in the Battle of Little Big Horn, where Custer and his Seventh Cavalry were wiped out by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse leading a force of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. But although the Indians won the battle, they lost the war. Less than a year later, Sioux leaders ceded the Black Hills to the United States in exchange for subsistence rations for their families on the reservation.

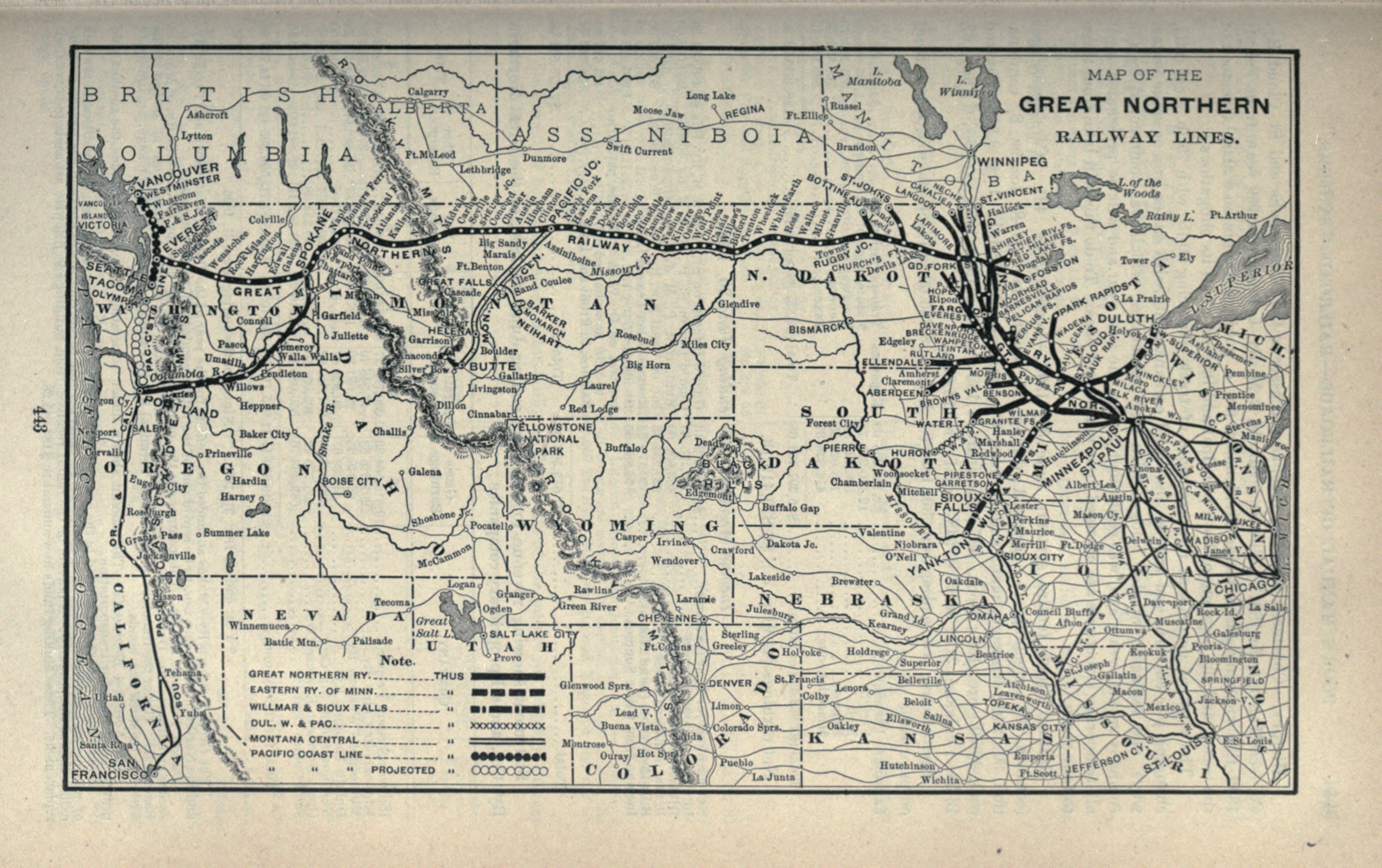

In contrast, Canadian-American railroad entrepreneur James Jerome Hill built his Great Northern Railroad line from St. Paul to Seattle during the last decades of the nineteenth century without causing a war and without receiving a single acre of free public land. The Great Northern bought land from the government to build its right of way and to resell to settlers. Hill claimed proudly that his railway was completed “without any government aid, even the right of way, through hundreds of miles of public lands, being paid for in cash.” The Great Northern system connected the Northwest with the rest of the nation through St. Paul, using a web of over 8,300 miles of track. And because Hill only built lines where traffic justified them rather than adding track just to collect free land, the Great Northern was one of the few transcontinental railroad companies to avoid bankruptcy in the Panic of 1893.

Regardless of the ways they were financed and built, the proliferation of railroads caused explosive growth. Chicago was a frontier village of 4,500 people in 1840. When Lincoln helped the Illinois Central receive the first land grant in 1851, the city’s population was about 30,000. Twenty years later Chicago was the center of a rapidly-growing railroad network, and the city held ten times the people. In 1880 Chicago’s population was over 500,000, and ten years later Chicago had over a million residents. We will take a closer look at the changes railroads brought to Chicago in a Chapter Seven.

Internal Combustion

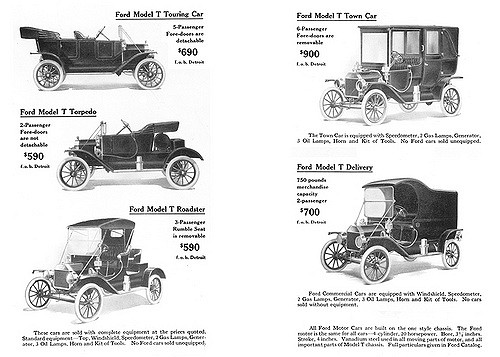

America’s transportation revolution did not end with steamboats and railroads and was not limited to public transportation technologies. The development of the automobile ushered in a new era of personal mobility for Americans. Internal combustion engines were inexpensive to mass produce and much easier to operate than steam engines. With the development of automobiles and trucks around the turn of the twentieth century, it no longer required a huge capital investment and a team of engineers to purchase and operate motorized transportation. Even the workers on Henry Ford’s assembly lines could aspire to owning their own Model Ts, especially after Ford doubled their wages to $5 a day in January 1914.

Engineers had experimented with building smaller machines using steam engines, and there were several examples in Europe and America of successful steam-powered farm tractors, trucks, and even a few horseless carriages. But internal combustion engines delivered much greater power relative to their mass, allowing smaller machines to do more work. The first internal combustion farm tractor was built by John Froehlich at his small Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company in 1892. Others began applying internal combustion to farm equipment, and between 1907 and 1912 the number of tractors in American fields rose from 600 to 13,000. Eighty companies manufactured more than 20,000 tractors in 1913. After an auspicious beginning, Froehlich’s little Iowa company grew slowly and began building farm tractors in volume only after World War I. The Waterloo company built a good product, and was acquired by the John Deere Plow Company in 1918. Deere remains the world leader in self-propelled farm equipment.

The first internal combustion truck was built by Gottlieb Daimler in 1896, using an engine that had been developed by Karl Benz a year earlier. World War I spurred innovation and provided a ready market for internal combustion trucks that were much less expensive than their steam-powered rivals. By the end of the war gasoline-powered trucks had overtaken the steam truck market. Most large trucks now burn diesel fuel rather than gasoline, using a compression-ignition engine design patented by Rudolf Diesel in 1892.

Internal combustion trucks and tractors, like cars, allowed people to go farther, carry more, and do more work than had been possible using human and animal power. And they were much more affordable than comparable steam-based vehicles and easier to build at a scale that encouraged individual use and ownership. Trucking eventually challenged rail transport, especially after the development of semi-trailers and the Interstate Highway System. Although the first diesel truck engines only produced five to seven horsepower, they advanced quickly. Indiana mechanic Clessie Cummins built his first, six-horsepower diesel engine in 1919. The business bearing his name is now a global corporation doing $20 billion in annual business, mostly in diesel engines. Cummins’s current heavy truck engine is rated at 600 horsepower.

While it is easy to focus on the inventions and technological innovations of the internal combustion era, we should not lose sight of the infrastructure improvements that made these innovations valuable. Without paved roads to run on, there would have been far fewer cars and trucks and their impact on society and the environment would have been much different. The biggest road-building project in American history was the construction of the Interstate Highway System, financed by the Federal-Aid Highway Acts of 1944 and 1956. Unlike the transcontinental railroad project of the 1860s, the Interstate Highway System was paid for by the federal government and the roads are owned by the states. The system includes nearly 47,000 miles of highway, and the project was designed to be self-liquidating, so that the cost of the system did not contribute to the national debt. In addition to the Interstate System, American states, counties, cities and towns maintain systems of roads totaling nearly four million miles, about two-thirds of which are paved.

Gasoline vs. Ethanol

The economic trade-off of internal combustion for the farmers and teamsters who first adopted it was that speed and power came at a price. Where horses and oxen were readily available in farm communities and were cheap to maintain, tractors and trucks were a substantial investment. And unlike horses and oxen, tractors and trucks needed to be fueled with petroleum that made them dependent on a faraway industry. However, this dependence was not inevitable. Henry Ford and Charles Kettering, the chief engineer at General Motors, had both believed that as engine compression ratios increased, their companies’ engines would transition from gasoline to ethyl alcohol. We are all aware that the shift to ethanol did not happen, but why it did not is less well-known and may surprise you.

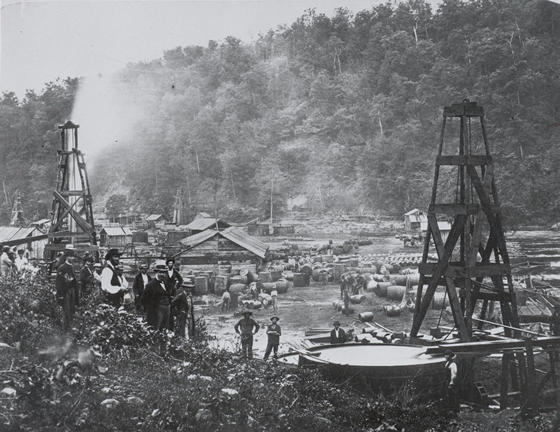

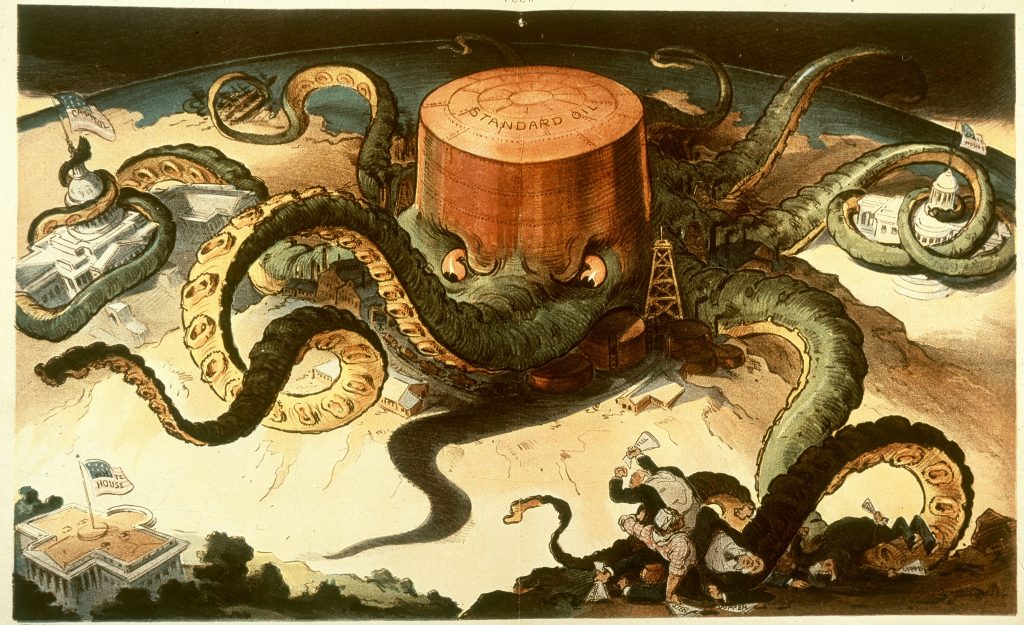

Most history books faithfully repeat the inaccurate story that Edwin Drake’s famous 1858 oil strike in Titusville Pennsylvania came just as the world was running out of expensive whale oil. Actually, there was a thriving market for alcohol fuel in the mid-nineteenth century United States. Ethanol was price-competitive with kerosene, and unlike kerosene it was produced by many small distillers, creating widespread competition that would continue to drive down prices. Unfortunately for ethanol producers and fuel consumers, the alcohol fuel industry was wiped out when the Lincoln administration imposed a $2.08 per gallon tax on distilled alcohol between 1862 and 1864. A gallon of Standard Oil kerosene still cost only 58 cents, so kerosene took over the American fuel market. Of course, after kerosene became the only available fuel, Standard Oil was free to raise prices as it saw fit.

But ethanol still had its advocates. The very first American internal combustion engine, built in 1826 by Samuel Morey, had used grain alcohol because it was inexpensive and readily available. Nearly a century later, Henry Ford’s Model T was designed to be convertible between kerosene, gasoline, and ethanol. General Motors chief engineer Kettering was convinced it was only a matter of time until ethanol became the fuel of choice.

So why aren’t we all driving cars running renewable fuels? Part of the answer, as you have probably already guessed, is that Standard Oil made the auto industry an offer they couldn’t refuse. The oil company used its vast distribution network to make gasoline available everywhere it was needed, and insured that the price was so low that competitors could not profit if they entered the market. Standard Oil pioneered the practice of pricing below their cost of production to run competitors out of the business. The profits of the company’s many other divisions subsidized their short-term losses on gasoline. Predatory pricing was one of the principal charges made against the company in the 1911 antitrust case that resulted in the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust.

But Standard Oil’s predatory pricing does not tell the whole story of why we do not run cars on ethanol. The rest of the story, if anything, is even more sinister. It has long been known that using gasoline at high compression results in engine knocking. It was also well-known that ethanol did not knock. Charles Kettering at General Motors had argued for years that the “most direct route which we now know for converting energy from its source, the sun, into a material suitable for use as a fuel is through vegetation to alcohol.” The technology was simple and Americans had been distilling alcohol fuels for generations. Unfortunately, Kettering worked for a corporation whose major shareholder was the Du Pont family, who also happened to own the largest corporation in the chemical industry. It would be impossible for DuPont to profit or for General Motors to gain a competitive advantage using alcohol fuels, since the distilling technology was universally available and the product was un-patentable. However, there was an extremely profitable alternative.

Tetraethyl Lead (TEL) was a lubricating compound that could be added to gasoline to eliminate knocking. General Motors received a patent on its use as an anti-knock agent, and Standard Oil was granted a patent on its manufacture which was later extended to include DuPont. The three companies founded Ethyl Corporation to market TEL and other fuel additives. Unfortunately, lead is a powerful neurotoxin, linked to learning disabilities and dementia. The federal government had misgivings about allowing lead additives, and in 1925 the Surgeon General temporarily suspended TEL’s use and government scientists secretly approached Ford engineers seeking an alternative. In the 1930s, 19 federal bills and 31 state bills were introduced to promote alcohol use or blending. But the American Petroleum Industries Committee lobbied hard against them. Under intense industry pressure, the Federal Trade Commission even issued a restraining order forbidding commercial competitors from criticizing Ethyl gasoline as unsafe. By the mid-1930s, 90 percent of all gasoline contained TEL. Airborne lead pollution increased to over 625 times previous background levels, and the average IQ levels of American children dropped 7 points during the leaded-gas era. By the 1980s, over 50 million American children registered toxic levels of lead absorption and 5,000 Americans died annually of lead-induced heart disease. When public concern continued to increase, the Ethyl Corporation was sold in 1962 in the largest leveraged buyout of its time. In the 1970s the newly-established Environmental Protection Agency finally took the stand other federal agencies had been afraid to take. The EPA declared emphatically that airborne lead posed a serious threat to public health, and the government forced automakers and the fuel industry to gradually eliminate the use of lead. TEL is now illegal in automotive gasoline, although it is still used in aviation and racing fuels. Unleaded gasoline is now used in all new internal combustion cars. But while pure ethanol has powered most automobiles in Brazil since the 1970s, most Americans continue to use a blend containing just 10% ethanol to 90% gasoline.

Global Cargo

Two additional forms of transportation became increasingly important as the twentieth century ended and the twenty-first century began. Commercial airplanes are only a little over a hundred years old and the first air cargo and airmail shipments were flown in 1910 and 1911. Air cargo was considered too expensive for all but the most valuable shipments until express carriers such as UPS and Federal Express revolutionized the shipping business in the 1990s. The global economy now measures air freight volumes in ton-miles. In 2014, the world shipped more than 58 billion ton-miles of goods. Air freight also allows perishable items like fresh fruits and vegetables to be transported across oceans and continents from producers to consumers. This is a big business. Over 75 million tons of fresh produce are air-shipped annually, worth more than $50 billion.

For nonperishable items, container shipping has created a single global market. Standardized containers were invented by a trucker named Malcolm McLean, who realized it would save a lot of time and energy if his trucks didn’t need to be loaded and unloaded at the port, but could just be hoisted on and off a cargo ship. McLean refitted an oil tanker and made his first trip in 1956, carrying fifty-eight containers from Newark to Houston. Current annual shipping now exceeds 200 million semi-trailer sized containers. Containers can be shipped by sea, rail, truck, and even air, allowing just-in-time operators like Wal-Mart to manage a supply chain that relies much less on warehoused inventory, and more on product in transit.

But just as shifting from horse power to a gasoline truck or tractor a hundred years ago involved economic trade-offs, shopping at Wal-Mart today introduces a new level of dependence. We not only rely on transportation systems and the fuels they run on, but also on supply-chain software, international trade agreements and currency fluctuations, and even on the political situations of faraway nations. As long as the costs of inputs like fuel and infrastructure like ports, highways, and open borders remains low, the global market is a great deal for the consumer and a source of immense profits to businesses and their shareholders. But a company like Wal-Mart is just as dependent on factors it cannot control as its customers are. If any of these factors change, who will bear the cost?

https://youtu.be/N9gfTs3JnAk

Further Reading

Bill Kovarik, “Henry Ford, Charles Kettering and the Fuel of the Future,” Automotive History Review , Spring, 1998. Available online at www.environmentalhistory.org

Marc Levinson, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Larger , 2006.

Vaclav Smil, Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations or 1867-1914 and their Lasting Impact , 2005

George Rogers Taylor, The Transportation Revolution, 1815-1860 , 1977.

Media Attributions

- World_airline_routes © Josullivan.59 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- EmpressWalkLoblaws-Vivid © Raysonho is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2000_VA_Proof © US Mint is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pittsburgh_1795_large © Samuel W. Durant is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Erie-canal_1840_map © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Travel time 1800-30 © US Census adapted by Dan Allosso is licensed under a Public Domain license

- PSM_V12_D468_The_clermont_1807 © Popular Science is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Riverboats_at_Memphis © Detroit Publishing Co. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Travel time 1857 © US Census adapted by Dan Allosso is licensed under a Public Domain license

- PJM_1088_01 © Rand McNally adapted by Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Custer_Staghounds is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1897_Poor’s_Great_Northern_Railway © Poor's Manual is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3640769879_2b88ee74ce_z © THF24864 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Map_of_current_Interstates.svg © SPUI - National Atlas is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Earlyoilfield (1) © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Standard_oil_octopus_loc_color © Udo J. Keppler is licensed under a Public Domain license

- every-citizen-can-get-his-share-our-democratic-way-of-sharing-the-limited-amount-1024 © US Government is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Container_ships_President_Truman_(IMO_8616283)_and_President_Kennedy_(IMO_8616295)_at_San_Francisco © NOAA is licensed under a Public Domain license

American Environmental History Copyright © by Dan Allosso is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Geography of Transport Systems

The spatial organization of transportation and mobility

Transport Revolutions in Human History

Source: adapted from R. Gilbert and A. Perl (2007) Transport Revolutions: Moving people and freight without oil, London: Earthscan / James & James.

Share this:

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Infrastructure: mass transit in 19th- and 20th-century urban america.

- Jay Young Jay Young Outreach Officer, Archives of Ontario

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.28

- Published online: 02 March 2015

Mass transit has been part of the urban scene in the United States since the early 19th century. Regular steam ferry service began in New York City in the early 1810s and horse-drawn omnibuses plied city streets starting in the late 1820s. Expanding networks of horse railways emerged by the mid-19th century. The electric streetcar became the dominant mass transit vehicle a half century later. During this era, mass transit had a significant impact on American urban development. Mass transit’s importance in the lives of most Americans started to decline with the growth of automobile ownership in the 1920s, except for a temporary rise in transit ridership during World War II. In the 1960s, congressional subsidies began to reinvigorate mass transit and heavy-rail systems opened in several cities, followed by light rail systems in several others in the next decades. Today concerns about environmental sustainability and urban revitalization have stimulated renewed interest in the benefits of mass transit.

- mass transit

- transportation

- urban growth

Mass transit—streetcars, elevated and commuter rail, subways, buses, ferries, and other transportation vehicles serving large numbers of passengers and operating on fixed routes and schedules—has been part of the urban scene in the United States since the early 19th century. Regular steam ferry service connected Brooklyn and New Jersey to Manhattan in the early 1810s and horse-drawn omnibuses plied city streets starting in the late 1820s. Expanding networks of horse railways emerged by the mid-19th century. A half century later, technological innovation and urban industrialization enabled the electric streetcar to become the dominant mass transit vehicle. During this era, mass transit had a significant impact on American urban development, suburbanization, the rise of technological networks, consumerism, and even race and gender relations. Mass transit’s importance in the lives of most Americans started to decline with the growth of automobile ownership in the 1920s, except for a temporary rise in transit ridership during World War II. In the 1960s, when congressional subsidies began to reinvigorate mass transit, heavy-rail systems opened in cities such as San Francisco and Washington D.C., followed by light rail systems in San Diego, Portland, and other cities in the next decades. As the 21st century approached, concern about environmental sustainability and urban revitalization stimulated renewed interest in the benefits of mass transit.

The history of urban mass transit in the United States is more complex than a simple progression of improved public transportation modes before the rise of the automobile ultimately replaced transit’s dominance by the mid-20th century. Transit history in American cities is rooted in different phases of urbanization, the rise of large corporate entities during the industrial era, the relationship between technology and society, and other broad themes within American history. At the same time, mass transit history shows the value of emphasizing local contexts, as the details of urban transit unfolded differently across the United States based on municipal traditions, environments, economies, and phases of growth.

Ferry Boats, Omnibuses, and the Beginnings of Mass Transit in the Early 19th Century

The ferry boats that regularly crossed the waters of a few American cities in the early 19th century provided an important precedent to the mass transit industry that emerged later in the century. Before the age of industrialization, the cities of the American merchant economy were primarily sites of commercial exchange of goods and services. Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and most other urban centers were dense, port cities located along rivers, bays, and other bodies of water. And while this geography facilitated the transshipment of goods, it also impeded the expansion of urban settlement. During the early 1810s, Robert Fulton, an engineer and inventor, established a regular ferry service using steam power. The service linked lower Manhattan with Jersey City over the Hudson River, as well as the village of Brooklyn , at the time a small suburban settlement across the East River. The early development of regular ferry service illustrates the dominant role that New York City would play in American urban mass transit—not surprising considering the city’s rapid demographic and physical growth and dominant position in the hierarchy of American cities during the 19th century. Ferries also demonstrate the early connections between transit and urban expansion, as the service allowed commuters living in areas such as the newly subdivided Brooklyn Heights neighborhood to overcome obstacles for continuous settlement posed by bodies of water. Typically, regular users of this service enjoyed above-average incomes and social positions. Unlike most working people, they could afford the expense of a daily fare. 1 By the 1860s, the annual ridership of New York’s ferry industry had expanded to more than 32 million people. Thirteen companies employed seventy steamboats for more than twenty different ferry routes. 2 Similar service had also spread to other northeastern cities, such as Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati. Ferry service is still an integral part of daily commuting in some cities today. Despite its success, however, ferry boat service could do little to improve transportation over land. 3

By the late 1820s, New York also became home to the first significant form of land-based mass transit: the omnibus. This operation—a large horse-drawn wheeled carriage similar to a stagecoach yet open for service to the general public at a set fare—originated in Nantes, France, in 1826 . Omnibus service spread to Paris two years later and to other French cities as well as London by 1832 . 4 Abraham Brower brought the service to New York in 1828 when he launched a route running a mile and a quarter along Broadway. Brower’s original vehicles, Accommodation and Sociable , held approximately twelve passengers. 5 Three years after Brower inaugurated service, more than one hundred omnibuses traveled on New York streets. 6 By the 1840s, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and other American cities had omnibus service. It spread from larger to smaller cities in subsequent decades. 7

The omnibus had weaknesses. Since most vehicles featured unpadded seats and typically travelled on uneven cobblestone roads (if paved at all), passengers experienced an uncomfortable ride. 8 The fare—generally 12 cents—was too expensive for most urban dwellers. Nonetheless, the omnibus initiated a “riding habit” of regular transit use within its main segment of users: members of the urban middle class. This growing demographic found private stagecoaches too expensive, but they had the affluence and desire to commute to work instead of walking. 9 Although getting around by foot remained the main source of mobility for most urban dwellers, the “walking city” was slowly eroding.

Horsecars: The “American Railway”

A vehicle with less surface friction could reduce the shortcomings that had plagued the omnibus. Horse streetcars—commonly known as horsecars —traveled on rail instead of road, and had numerous advantages over the omnibus. The use of rails provided a faster, quieter, more comfortable ride, while enabling a more efficient use of horse power. This fact allowed for larger cars that carried approximately three times as many riders as the omnibus. Importantly, the horsecar’s lower operating cost per passenger mile translated to a cheaper fare for users (typically 5 cents compared to the 12-cent omnibus fare) and a growing “riding habit” within the American urban population. 10 Horsecars reduced the time and cost of commuting to and from the central core, and, thus, they expanded the area of development along the urban fringe. Following a slow start, other American cities adopted horsecars by the 1850s, part of the wider context of rampant urbanization during the second half of the 19th century. Typically, a private company ran lines under a franchise awarded by the municipality that outlined the public roads on which the company could build rails and operate routes, along with other stipulations. By the end of the 1850s, New York, New Orleans, Brooklyn, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Cincinnati provided horsecar service. Further expansion developed during the 1860s. 11 Two decades later, almost twenty thousand horsecars traveled on more than thirty thousand miles of street railway across the United States. Such expansion was particularly notable in contrast to comparatively slower growth in Europe (where people called the technology “American Railways”). 12 The horsecar’s initial development in the United States, and its early spread across the country, exemplified how the country was often at the forefront of transit use and technological innovation during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century.

The world’s first horsecar line began service in 1832 , when the New York and Harlem Railroad Company inaugurated a horse-powered rail car route along Fourth Avenue. The franchise owners, including banker John Mason, intended the line to serve as the first stage of a passenger steam railway linking lower Manhattan to Harlem. However, fears of noise, smoke, and boiler explosions from those living along the right-of-way prompted the city to prohibit the railroad from operating steam engines within the built-up area south of Twenty-Seventh Street, so the company relied upon horse power within the restricted area. 13 Despite the operating advantages of horsecars, its “technology transfer” to other American cities was slow until the early 1850s. This phenomenon reinforced the value of local contexts, as horsecar lines developed differently in each city based on factors such as local politics, geography, and population density. Horsecars—and the rails upon which they travelled—began a process of redefining the meaning of city streets that continued with electric streetcars and automobiles. The street became more a place for mobility, diminishing the centrality of sociability, recreation, and other traditional street uses. Initially, popular sentiment opposed the placement of rails along streets, especially since rails were not flush with the street surface and impeded cross movement until the invention of grooved rails in 1852 . That same year, New York saw its first horsecar operation distinct from steam railroads, and the service soon spread to many other American locales. 14

Historians Joel Tarr and Clay McShane demonstrate that horsecars exemplify how the rise of industrialization and urbanization during the 19th century led to a growing exploitation of horse power. Ironically, steam power, an essential component of the first Industrial Revolution, created a greater demand for this older form of energy in industrial cities. 15 Yet the horsecar’s reliance on these “living machines” presented the greatest weakness of the technology, especially as cities sought to expand their systems once easily commutable distances from the urban fringe via horsecar were reached. Horses were expensive to maintain. They ate their value in feed each year, required large stables and care from veterinarians, stablehands, and blacksmiths, and their average work life lasted less than five years. 16 In terms of social costs, horses produced massive amounts of pollution as their manure and urine fell on city streets. And once horses met their ultimate fate, their bodies had to be removed. New York alone disposed of fifteen thousand horse carcasses annually. 17 Sudden disease outbreaks were common. The most dramatic occurred in 1872 , when an equine influenza epidemic —the “Great Epizootic”—hit North America (especially eastern seaboard cities). Thousands of horses died during the epidemic, which created operational upheaval for the horsecar industry. Not surprisingly, the event further reinforced the need for cheaper, more reliable forms of transit power. 18

Steam was one alternative source of power. It had provided power for ferry services since the 1810s and passenger railways two decades later. By the mid-19th century, commuter railways using steam locomotives (essentially short-haul passenger rail) connected affluent residents living in small suburban areas to places of work and entertainment in large cities. For example, upper-middle-class towns, such as New Rochelle and Scarsdale in Westchester County, New York, grew with commuter rail service to New York City, while Evanston, Highland Park, Lake Forest, and other commuter towns emerged around Chicago. 19 Yet steam power presented challenges for urban transit. Many city dwellers living along crowded streets considered the noise, pollution, and other dangers associated with the technology to be nuisances. Steam operation also generally cost more than horse power until the 1870s. A few New York companies gambled on steam-powered conveyances during the 1860s, but they all soon ceased their experiments. 20 Nonetheless, transit companies in greater New York and Chicago began building elevated railroads using steam power above urban thoroughfares. This proved to be among the earliest forms of rapid transit, since vehicles operated on their own right-of-way, not in mixed traffic. By 1893 , Jay Gould’s New York Elevated Railroad Company carried half a million daily passengers from lower Manhattan to the Bronx, while Chicago saw the first line of its “L” system open in 1892 . Although short-lived “elevateds” existed in the smaller cities of Sioux City, Iowa, and Kansas City, Missouri, high capital costs made them mostly a big city phenomenon unlikely to become a dominant mode of transit across the United States. 21 Elevateds also darkened the street below. Once electricity became a possible power source by the 1890s, city dwellers clamored for rapid transit to burrow underground.

Power generated from a stationary central source—rather than within a moving locomotive—offered another alternative. Cable cars traveled on rail, similar to horsecars and steam railways, but these vehicles clasped on a moving cable within a street conduit. This feature eliminated much of the noise, smoke, and danger of boiler explosions that plagued urban steam locomotives (although such nuisances were still present at the stationary power source). Cable car operation began in San Francisco in 1873 , when Andrew Hallidie began his service on Clay Street . San Francisco’s hilly terrain required four horse teams to pull a single omnibus, with some hills too steep for any kind of horse service. 22 Since various transit experiments in steam, compressed air, chemical engines, and electricity failed to produce an inexpensive method of propulsion, cable cars seemed the best alternative to horse power by the 1870s. Following Hallidie’s successful operation, most large cities across the United States built cable car networks. 23

With hindsight, the cable car emerged as a temporary solution for the transit industry until the refinement of a more efficient power distribution method. Cables had advantages over horse power, but they also carried particular weaknesses. Cables were always under the threat of snapping. Maintenance and replacement constituted a complex, expensive process that negatively affected service. Ice buildup produced issues in colder cities. The cable had to run at the same capacity no matter the service level, which meant power generation could not diminish at off-peak times. Twenty years after Hallidie’s first run on Clay Street, more than three hundred miles of cable car tracks had been laid across the United States. But numbers declined soon after electric streetcar operation became practical in the 1890s. By 1913 , only twenty miles of cable car track were still in use. 24 Electric streetcars and other electric transit technologies exacerbated the changes in urban life that horsecars and cable cars had unleashed.

Transit Becomes Electric

Technological innovations, demand from the transit industry for improved operations, and a desire for mobility enabled the electric streetcar to become the dominant mass transit vehicle in the United States by the turn of the 20th century. The streetcar’s use of electricity makes it a key technology of the second Industrial Revolution. “[N]o invention,” urban historian Kenneth Jackson has argued, “had greater impact on the American city between the Civil War and World War I than the visible and noisy streetcar and the tracks that snaked down the broad avenues into undeveloped land.” 25 The idea of transmitting electrical current to move vehicles had existed since the 1840s, but no practical technique could generate sufficient electrical power. Experiments with battery power also failed in terms of feasible, everyday operation. 26 Early streetcar pioneers such as Leo Daft and Charles van Depoele made significant advances to the technology; however, Frank Sprague (1857–1934) is most commonly associated with the vehicle’s development. Similar to names associated with other critical technologies, Sprague was not the sole “inventor” of the electric streetcar. Rather, as transit historian Brian J. Cudahy explains, Sprague’s success derived from “his ability to blend aspects of previous experiments with his own developments into a fully orchestrated whole.” 27 A former Edison employee, his key technical contribution was a trolley poll and wheel design that overcame previous flaws whereby overhead electrical wires detached from vehicles (and thus the power source). Sprague’s system also demonstrated operational reliability and financial feasibility when it was put to the test along twelve miles of track for the Union Passenger Railway in Richmond, Virginia, in 1888 . Twelve years later, 90 percent of all streetcars in the United States relied on his patents, and few horsecars were still in operation. 28

Street railway companies quickly adopted electricity. Often, they used existing rails and even former horsecar vehicles. 29 Electric streetcars transformed the transit industry. New forms of expertise related to electricity replaced veterinarians, blacksmiths, and other horse-related professions. The new technology also generated mergers with large companies swallowing up smaller enterprises, monopolizing service in urban areas, and employing corporate business forms in order to raise capital needed for investment in electricity infrastructure (in some cases, electrical utility companies were also transit providers). Transit remained within the private market in most American cities until the second half of the 20th century, but the organizational structure of the industry became more complex. 30

Electric streetcars rapidly spread across the country. Like horsecars decades earlier, electric streetcars accommodated heavier passenger loads compared to predecessors. This reduced passenger cost per mile, lowered fares, and stimulated greater transit use by wider segments of society. Two years after Sprague’s Richmond success, the vehicle carried twice the number of passengers in the United States compared to the rest of the world, with thirty-two thousand electric streetcars traversing American streets from small towns to major metropolises—a number that nearly doubled by the turn of the century. 31

Electric traction also removed an obstacle for underground transit. The London Underground had operated steam-powered trains when it opened in 1863 , but most commentators believed Americans would avoid smoke-filled subway tunnels. The massive construction cost also impeded subway building. In 1894 , the Massachusetts legislature authorized Boston to build the first subway in the United States. The line, which was completed four years later, buried 1.5 miles of a busy streetcar under Tremont Street’s retail district. The Boston Transit Commission, a public body, financed construction, while the private West End Street Railway operated the line and serviced its debt. 32 Public money was also required to build the country’s largest subway network in New York—foreshadowing the growing role of the state in mass transit in the second half of the 20th century. In 1904 , the Interborough Rapid Transit Company’s service began connecting the Bronx to Manhattan, followed by the construction of hundreds of more miles of subway in New York during subsequent decades. 33

The Effects of Electric Streetcars on Urban Life

Streetcars and other forms of electric traction had a tremendous influence on the shapes and sensations of urban life during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In many cases, the technology exacerbated trends that began with the horsecar. Streetcars continued the horsecar’s role in enabling the seemingly contradictory yet related forces of centralization and dispersal in American cities. In essence, this entailed the general separation between major commercial activities in the downtown and districts of residence and other activities, such as manufacturing, in less dense areas surrounding the core and along the urban fringe. The American walking city—in which the dominant mode for the journey to work was by foot—came to an end, although many workers still walked to their places of employment.