Tourism Product Life Cycle

Tourism Product Life Cycle : The Product in Tourism Industry is different as tourism industry is a service industry. It provides products that are nothing but experience and services. The service product refers to an activity or a set of activities that a marketer offers to perform, resulting in satisfaction of a need of the customer or the target market in return of money. Products that fulfil all the pleasure, leisure or business requirements and wants of tourist at places other than their own place of origin are called as tourism products.

A product in tourism can be either a tangible item or Intangible item. Tangible item such as a comfortable seat in Bus, Train or aircraft or the food served in a restaurant or aircraft and Intangible item such as the quality of services provided by an Aircraft or scenic beauty at a hill Station. So, we can say that in almost all the cases, the tourism product is a mix or blend of both intangible and tangible items. This combination of different components results in giving the tourist the total travel experience and satisfaction.

Also read Tourism

Philip Kotler (Kotler and Keller 2006) defines the concept ‘service’ as a product from marketing viewpoint. “A service is any action or performance that one party offers to another that is importantly intangible and does not result in the ownership of anything. Its production might or may not be tied to a physical product”.

Meaning of tourism Product life cycle

Tourism product is a group of various components and elements which are combined together to satisfy the needs and wants of the consumers. The product in tourism industry is the complete experience of the tourist from the point of origin to the destination point and back to the origin point. The product in Tourism may be defined as the ‘sum total of physical and psychological satisfaction it provides to the tourist from the origin point to the destination and during their travelling route’.

The raw material in tourism industry is the natural beauty, Climate, History, Culture and people of the destination and some other important elements are the existing facilities or the infrastructure such as water supply, electricity, roads, transport, communication, services and other ancillary services. If any of these elements get missing, then it will completely destroy the whole experience of the tourist. Tourism products are offered in the market with some cost i.e. money. A Product could therefore be defined by its three characteristic:

- The product must be offered

- It should satisfy some need or needs of the customers

- It should be exchanged for some value

So, we can say that if the Tourism Product i.e. the sum total of a country’s tourist attractions, transport systems, hospitality , entertainment, and infrastructure is well designed and developed and then offered to the tourist this will ultimately result in consumer satisfaction. These are nothing but various services offered to the tourists, and falls under the category of service product. Tourism product is the prime reason for tourist to choose a destination. Tourism product helps in earning revenue for the destination. So all the tourism product should be properly preserved and promoted

Tourism product life Cycle

Tourism destinations are dynamic in nature. The destination is a gathering of products. Destinations like product’s experience life cycles. The concept “Tourism Product life cycle” is used to explain the development of a particular destination and the succeeding levels they go through over time to time. In tourism and tourism related businesses, achievement means knowing this whole procedure.

The theory of Tourism product life cycle has the potential to be put into practice while planning for tourist destinations. This idea provides clear picture for understanding the process of change within tourist destinations. It provides a tool to conceptually predict the long term difference so that policies and plans could be evolved for proper land use, economic development and marketing without harming environment.

Various models were made from time to time that examine the evolution of destinations, although mostly are just descriptive. With the exposure of mass tourism, a larger number of researchers have suggested evolutionary models in which the concept represents additional stages of destination such as saturation and decline. This contributes on the belief that all the tourism destinations go through some stages. As a result any kind of tourist product has to cross several phases which are known as Tourism Product life cycle.

The following stages of product life cycle are explained considering “destination” as a tourism product, as without a destination tourism cannot take place and is one of the most important tourism product.

I. Exploration Stage:

It is the first stage of tourism product life cycle. In this stage new tourism products are discovered and introduced. Small number of visitors start coming to the unspoiled destination. Mostly they are the adventure seeker and nature lovers start travelling to the unexplored destination with the aim to experience different types of activities and adventure.

Tourist those who are searching for different varieties in their vacation may find a places which are special on the basis of its natural beauty, traditions, history, landscape and culture. At this stage there will be no or limited tourist services accessible. Since there is no awareness about tourism and its benefits so there is no involvement of local people in tourist money making activities. There is very less social and economic impact because tourists are very few and facilities available are not so good and no proper infrastructure is developed for the purpose of tourism activities.

Also read Tourism Product Concept

II. Involvement Stage:

This is the second stage of tourism product life cycle. In this stage the number of visitors starts increasing gradually and the host community of that destination starts knowing about the growth in the movement to their place/destination. And further these hosts start getting engaged themselves in tourism related activities. Even the local authorities also start participating in the tourism related activities.

Local communities also start setting up their own business to provide various tourist related services and facilities such as accommodation, meals, guides services, and transportation. Involvement in these tourist activities also improve the quality of life for the locals and also create job opportunities. And also helps the local community to earn money and fulfil their wants and desires. Thus tourist destination starts emerging and good infrastructure is built and developed. Marketing, advertising and publicity is commenced in this stage.

Since locals start involving themselves in the tourism activities, they learn about different natural resources in their surroundings and also knows about the value of their culture and traditions. Through involvement activities awareness for environment protection also starts increasing.

Involvement of the local community also help to improve their basic needs like Hygienic food, Health and Medical facilities, education etc. there is also improvement in the number of people’s involvement in different activities and job opportunities starts to rise or increase. This increase participation and job opportunities help to improve the economic and social structure of that particular destination. This is the stage when locals start to identify opportunities for business or start-ups and scope for growth certainly rises. By the name of involvement locals start to use their culture and traditions as tourism products. For attracting more number of tourists and which further tends to create USPs and improvement in the destination image.

III. Development Stage:

Development stage is the third stage of tourism product life cycle. Where the number of tourists arrivals are much higher from the previous stage. And at this point foreign investment is attracted to the destination due to commencement of a well-defined tourism market. Therefore international hotel chains, food units and entertainment facilities starts taking interest in the destination and set up their business with the aim of providing world class facilities and earn profits out of the destination.

Many Big companies start investing in tourist services at the destination by seeing the emerging potential of the area. Development rate starts increasing which further improves the quality of life for the local communities, accessibility of the destination is improved. Marketing & advertising becomes prime intensive. Modernized infrastructure is built. Natural and Man-made attractions are developed for tourist.

Also read Travel Agents and Tour Operators

Equal involvement of Government, locals and private players can be seen in this stage. This also helps in attracting more and more number of tourist and large number of jobs for local community are created. At this stage marketing and promotional campaigns activities usually play an important role as the destination starts to become favorites for many travellers.

Various efforts are made by various stakeholders for the growth of the destination and increase tourist movement to the given destination. At this stage there is a huge scope for job opportunities in different sectors and for investment in the tourism related businesses. Development stage also boost the economy of the destination and helps in creating foreign exchange for the growth of the nation.

IV. Consolidation Stage:

This is the fourth stage of tourism product life cycle. In this stage the local economy is likely controlled by tourism activities. In this stage, the local community starts earning good amount of financial resources which helps in improving the quality of life for the hosts. The local economy in this stage becomes dependent on tourism activities. The tourist volume at the destination is continuously increasing. Promotional and marketing efforts are increased to attract more visitors towards the destination.

You can read more on travel motivation

Tourist services are provided by both the national and international suppliers/companies. Slowly the destination starts to lose the appeal as the products offered here starts to get outdated and negative impacts of tourism activities can be seen on the destination, its natural beauty, its natural resources and environment, on the society, on the attractions and so on. If proper steps and policies are formed at this stage the life of the destination can be increased for a longer period of time and the destination can sustain for the forthcoming generations.

At this stage proper implementation of the planned policies needs to be applied and preservation of the destination and its resources can be done. In this stage the local communities also start to shift from other industries or activities like farming and fishing, which results in suffering of these industries. The older infrastructure like buildings are converted into lodging units like heritage hotels, guest house or homestays. Therefore some of the old buildings also loose there unique characteristics or charm or become unattractive and a lower client base might result.

V. Stagnation Stage:

This is the fifth stage of tourism product life cycle. In this stage the carrying capacity of the destination reaches to its last limit or is exceeded. Which finally results in economic , social, cultural and environmental problems. Artificial attractions starts to replace the natural or cultural Attractions and the destination becomes more fashionable. This will result in loss of original features of the destination which means that the Destination has started losing its charm and USPs. And there is a gradual fall or decrease in the number of tourists visiting that particular destination.

Also there is an increase in the competition from other competitors, loss of authentic and original features and rowdiness may arise. Which further results into decline in the level of tourist visits and local businesses and services are effected to large extents? For example: If the destination is a beach and it is now very crowed and full of garbage and rubbish, this will certainly stop the growth of the destination. Strong decisions need to take at this point of time otherwise, the number of tourist visiting the destination will start declining and this will affect the local business and services. Which would finally impact the economy, society and the present environment of the destination.

VI. Decline or Rejuvenation Stage:

This is the final and Sixth stage of Tourism product life cycle. From the point of stagnation onwards there are two types of possibilities i.e. Decline in the tourist movement or rejuvenation means re-growth or re-introduction of the destination with new tourism products like attractions and other tourist facilities.

There can be slow or rapid decline of a particular destination. Visitor’s number will start falling or decreasing and regular visitors are replaced by tourists looking for a affordable/cheap vacation or trip. The movement of tourists starts to shift and tourists are attracted to new and beautiful destinations. The destination becomes a tourism slum or finds itself devoid of tourism activity altogether.

Since there is a rapid fall in the number of tourists at the destination as there are more negative impacts that can be seen on the destination. And the attractions starts to completely loose its charm and USPs. Problems like high pricing, overcrowding, environmental pollution, political instability, high crime rates and overrated attractions are some of the major reasons for decline and stagnation of tourist arrivals at a particular destination. Which results to fall in the number of tourists visiting the destination and the destination certainly declines or fall.

Rejuvenation is a reasonable change and establishment of the resources base. Large number of investments is done by private companies or by government, or by both for the transformation of the destination and starts to introduce new tourism product line. As they also start to create a new set of artificial attractions within the original destination to boost its popularity and attract more tourists.

Previously unexploited natural resources are also utilized. This will ultimately lead to the beginning of another cycle. The reason for rejuvenation of a destination are proper research and analysis on product development, right steps by the local administration, identifying new areas for development, creation of world class infrastructure etc. Otherwise, a permanent decline of the destination will sets in.

You Might Also Like

Classification of museums

Biosphere Reserves in India

Classification of Airline Tickets

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model: A simple explanation

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Prof. Richard Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is a core theoretical underpinning for many tourism research and analyses. It is also a core component of many travel and tourism management curriculums. But what does it mean?

In this article I will give you a simple explanation of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model. I promise, by the end of this short post you will understand exactly how this model works and why it is so important in travel and tourism management….

So what are you waiting for? Read on to find out more..

What is Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model?

How did the tourism area life cycle model come about, #1 exploration, #2 involvement, #3 development, #4 consolidation, #5 stagnation, #6 decline or rejuvenation, the positive aspects of butler’s tourism area life cycle model, the negative aspects of butler’s tourism area life cycle model, to conclude.

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model provides a fundamental underpinning to travel and tourism management of destinations. Not sure what that means? Well, basically, it is the theory underneath the story.

It sounds complicated on the outside, doesn’t it? But actually, it really isn’t complicated at all!

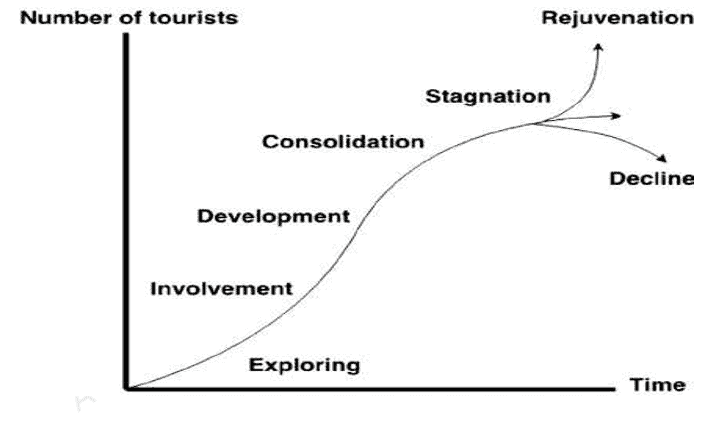

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is a simplistic linear model. Using a graph, it plots the different stages in tourism development in accordance with the x and y axis of tourist number growth and time. Within this, Butler’s model demonstrates 6 stages of tourism development.

OK, enough with the complicated terminology- lets break this down further. What is Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model in SIMPLE language?

To put it simply; Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is a line graph that shows the different stages in tourism development over time.

Whilst sustainable tourism has been a buzz word for a while now, it wasn’t always the focus of tourism planning and development .

Back in the 1970s and 1980s many tourism entrepreneurs and developers were not thinking about the longevity of their businesses (this still happens a lot, particularly in developing countries, where education and training may be limited). These business men and women simply saw Dollar signs and jumped right in.

The result? Ill-thought out plans and unsustainable tourism endeavours.

Examples of unsustainable tourism with ill-thought out long term plans include: Overtourism in Maya Bay, Thailand , littering on Mount Everest and the building of unsightly high-rise hotels in Benidorm.

Professor Richard Butler wanted to give stakeholders in tourism some guidance. Something generic enough that it could be applied to a range of tourism development scenarios; whether this be a destination , resort, or tourist attraction .

This saw the birth of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model.

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model: How does it work?

OK, lets get down to it- how does this theory actually work?

Well, actually it’s pretty simple.

Butler created a visual, graphical depiction of tourism development. People like visuals- it helps us to understand. You can see this below.

As you can see in the image above, Butler identified six stages of tourist area evolution.

The axis do not have any specific numbers, which means that this model can easily be applied to a number of different situations and contexts.

The intention is for those who are involved with tourism planning and development to use this model as a guide. This can encourage critical thinking and the development of alternative and contingency plans. It helps to develop sustainable tourism practices.

The six stages of tourist area evolution

Butler outlined six specific stages of tourism development. Well, actually it’s five specific stages and the last ‘stage offers a variety of outcomes (I’ll explain this shortly).

Butler wanted to demonstrate that tourism development, like many things in life, is not a static process. It experiences change. Changes happens for many reasons- growth in tourism numbers, changes in taste, marketing and the media, external influences such as natural disasters or terrorism.

Butler’s model demonstrates that tourism destinations or attractions will typically follow the path outlined, experiencing each of the six stages. This will happen at different paces and at different times for different types of tourism development.

Below, I will explain which each stage of tourist evolution is referring to.

The exploration stage marks the beginning.

Tourism is limited. The social and economic benefits are small.

Tourist attractions are likely to be focused on nature or culture .

This is the primary phase when Governments and local people are beginning to think about tourism and how they could capitalise and maximise their opportunities in this industry.

This is the start of tourism planning .

The involvement stage marks the beginning of tourism development.

Guest houses may start to open. Foreign investors may start to show an interest in development. Governments may be under pressure to develop transport infrastructure and community resources, such as airports, road layouts and healthcare provision.

The involvement stage may mark the emergence of seasonality in tourism.

During the development stage there will be lots of building and planning.

New roads, train stations and airports may be built. New tourist attractions may emerge. Hotels and hospitality provisions will be put in place.

During the development phase there will likely be an increase in marketing and promotion of the destination. There could be increased media and social media coverage.

During this time the tourist population may begin to out-number the local population. Local control becomes less common and top-down processes and international organisations begin to play a key role in the management of tourism.

During the consolidation stage tourism growth slows. This may be intentional, to limit tourist numbers or to keep tourism products and services exclusive, or it may be unintentional.

There will generally be a close tie between the destination’s economy and the tourism industry. In some cases, destinations have come to rely on tourism as a dominant or their main source of income.

Many international chains and conglomerates will likely be represented in the tourism area. This represents globalisation and can have a negative impact on the economy of the destination as a result of economic leakage .

It is during this stage that discontent from the local people may become evident. This is one of the negative social impacts of tourism .

The stagnation stage represents the beginning of a decline in tourism.

During this time visitor numbers may have reached their peak and varying capacities may be met.

The destination may simply be no longer desirable or fashionable.

It is during this time that we start to see the negative impacts of overtourism . There will likely be economic, environmental and social consequences.

The final stage of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model represents a range of possible outcomes for the destinations along the spectrum between rejuvenation and decline.

The outcome of this will depend upon the plans and actions of the stakeholders of said tourism development project.

Complete rejuvenation can occur through major redevelopments. Perhaps new attractions are added, sustainable tourism approaches are adopted or there is a change in the target market.

Modest rejuvenation may occur with some smaller adjustments and improvements to the general tourism infrastructure and provision.

If changes do not occur, there may be a slow continuation of tourism decline.

In severe circumstances, there may be a rapid decline of the tourism provision. This is likely due to a life-changing event such as war, a natural disaster or a pandemic.

What happens after complete decline?

Sadly, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in many tourism destinations and attractions experiencing the drastic decline identified in Butler’s most pessimistic scenario.

These areas will likely either experience one of two possible outcomes-

1- Tourism infrastructure will be used for alternative means. Hotels may become retirement homes and tourism attractions will be replaced with non-tourism facilities. The area may become run down and impoverished as a result of the economic loss.

2- Tourism development will start again. Many destinations have taken this opportunity to re-evaluate and reimagine their tourism infrastructure. Improvements can be made and more sustainable practices can be adopted. The destination will start again at the beginning of Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle.

Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model is great because it provides simplistic theoretical guidance to tourism stakeholders.

Those who are just starting out can use this model to plan their tourism infrastructure and development. It encourages critical thinking and long-term thinking.

However, Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model can also be criticised for its simplicity.

Without sufficient knowledge and training, tourism stakeholders may not understand this model and therefore may not adequately utilise it.

The linear approach taken with this module does not account for unique and unaccounted for occurrences. In other words, not every destination or attractions may follow these stages in this way.

Lastly, being developed back in 1980, Butler’s model fails to account for many of the complexities of today’s travel and tourism industry. The biggest downfall is the redundancy of references to sustainability.

Sustainability is at the core of everything that we do in today’s world, so it is perhaps outdated thinking to assume that all destinations will reach consolidation in the way that it is represented in Butler’s model.

Wow, who knew I would be able to write 1500 all about Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle Model? Well, in actual fact, I could easily write another 1500! This theory is an important part of the tourism curriculum and is important for travel and tourism students to understand, as well as a variety of tourism stakeholders.

Want to learn more? Follow along on social media or subscribe to my newsletter for conceptual and practical travel tips and information!

Liked this article? Click to share!

- 2030 Agenda

- Foro ALC 2030

- 75 Anniversary

- About ECLAC

Tourism life cycle, tourism competitiveness and upgrading strategies in the Caribbean

View publication

Press Enter to see the available file formats. Use Tab to choose one.

Description

In the 1980s Butler adapted the life cycle product model to the tourism industry and created the “Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model”. The model recognizes six stages in the tourism product life cycle: exploration, investment, development, consolidation, stagnation and followed, after stagnation, by decline or revitalization of the product. These six stages can in turn be regrouped into four main stages. The Butler model has been applied to more than 30 country cases with a wide degree of success. De Albuquerque and Mc Elroy (1992) applied the TALC model to 23 small Caribbean island States in the 1990s. Following De Albuquerque and Mc Elroy, the TALC is applied to the 32 member countries of the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) (except for Cancun and Cozumel) to locate their positions along their tourism life-cycle in 2007. This is done using the following indicators: the evolution of the level, market share and growth rate of stay-over arrivals; the growth rate and market share of visitor expenditures per arrival and the tourism styles of the destinations, differentiating between ongoing mass tourism and niche marketing strategies and among upscale, mid-scale and low-scale destinations. Countries have pursued three broad classes of strategies over the last 15 years in order to move upward in their tourism life cycle and enhance their tourism competitiveness. There is first a strategy that continues to rely on mass-tourism to build on the comparative advantages of “sun, sand and sea”, scale economies, all-inclusive packages and large amounts of investment to move along in Stage 2 or Stage 3 (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico). There is a second strategy pursued mainly by very small islands that relies on developing specific niche markets to maintain tourism competitiveness through upgrading (Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, British Virgin Islands and Turks and Caicos), allowing them to move from Stage 2 to Stage 3 or Stage 3 to a rejuvenation stage. There is a third strategy that uses a mix of mass-tourism, niche marketing and quality upgrading either to emerge onto the intermediate stage (Trinidad and Tobago); avoid decline (Aruba, The Bahamas) or rejuvenate (Barbados, Jamaica and the United States Virgin Islands). There have been many success stories in Caribbean tourism competitiveness and further research should aim at empirically testing the determinants of tourism competitiveness for the region as a whole.

Table of contents

.--I. Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) Model and Concurrent Tourism Strategies.--II. Tourism Competitiveness and Tourism Performance in the Caribbean.--III. Tourism Life Cycle in the Caribbean: From Mass Tourism to Upgrading.--IV. Concluding Remarks

You might be interested in

Tourism in the Caribbean: competitiveness, upgrading, linkages and the role of public private...

CEPAL Review no.104

What kind of State? What kind of equality? XI Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and...

Ageing and development in a society for all ages

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

The Tourism Area Life Cycle, Vol. 1

Applications and modifications.

- Edited by: Richard Butler

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Channel View Publications

- Copyright year: 2006

- Audience: College/higher education;

- Main content: 408

- Keywords: TALC ; tourism development ; tourism area life cycle ; evolution of tourism areas ; TALC in heritage settings ; tourist destinations ; tourism rejuvenation

- Published: January 11, 2006

- ISBN: 9781845410278

- Acerca de este repositorio

- Términos de uso

- Acerca de la CEPAL

Tourism life cycle, tourism competitiveness and upgrading strategies in the Caribbean

Título de la revista, issn de la revista, título del volumen, símbolo onu.

In the 1980s Butler adapted the life cycle product model to the tourism industry and created the “Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model”. The model recognizes six stages in the tourism product life cycle: exploration, investment, development, consolidation, stagnation and followed, after stagnation, by decline or revitalization of the product. These six stages can in turn be regrouped into four main stages. The Butler model has been applied to more than 30 country cases with a wide degree of success. De Albuquerque and Mc Elroy (1992) applied the TALC model to 23 small Caribbean island States in the 1990s. Following De Albuquerque and Mc Elroy, the TALC is applied to the 32 member countries of the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) (except for Cancun and Cozumel) to locate their positions along their tourism life-cycle in 2007. This is done using the following indicators: the evolution of the level, market share and growth rate of stay-over arrivals; the growth rate and market share of visitor expenditures per arrival and the tourism styles of the destinations, differentiating between ongoing mass tourism and niche marketing strategies and among upscale, mid-scale and low-scale destinations. Countries have pursued three broad classes of strategies over the last 15 years in order to move upward in their tourism life cycle and enhance their tourism competitiveness. There is first a strategy that continues to rely on mass-tourism to build on the comparative advantages of “sun, sand and sea”, scale economies, all-inclusive packages and large amounts of investment to move along in Stage 2 or Stage 3 (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico). There is a second strategy pursued mainly by very small islands that relies on developing specific niche markets to maintain tourism competitiveness through upgrading (Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, British Virgin Islands and Turks and Caicos), allowing them to move from Stage 2 to Stage 3 or Stage 3 to a rejuvenation stage. There is a third strategy that uses a mix of mass-tourism, niche marketing and quality upgrading either to emerge onto the intermediate stage (Trinidad and Tobago); avoid decline (Aruba, The Bahamas) or rejuvenate (Barbados, Jamaica and the United States Virgin Islands). There have been many success stories in Caribbean tourism competitiveness and further research should aim at empirically testing the determinants of tourism competitiveness for the region as a whole.

TIPO DE DOCUMENTO

- Tabla de Contenido

.--I. Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) Model and Concurrent Tourism Strategies.--II. Tourism Competitiveness and Tourism Performance in the Caribbean.--III. Tourism Life Cycle in the Caribbean: From Mass Tourism to Upgrading.--IV. Concluding Remarks

Temas CEPAL

País/región.

- Descripción

- Subtemas ONU

- Subtópicos CEPAL

- Región/País

Colecciones

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

THE TOURIST PRODUCT LIFE CYCLE

2008, Theoretical Developments in Contemporary Economics, „Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad, ISBN 978-52-0489-1, p. 185-191

In tourism and tourism related industries, success means understanding this process. Marketing is creating and promoting a product (ideas, goods or services) that satisfies a customer's need or desire and is available at a desirable price and place.

Related Papers

Sergiu Rusu

Charla Estocapio

Nadir Ayrad

Adina Nicoleta Candrea

REVISTA ECONOMICĂ

Cristina Mahika

Ijetrm Journal

MANAGEMENT AND MARKETING

Gheorghe G Săvoiu

Olimpia Ban , Ada Mirela Tomescu

The concept of “wellness” has several meanings, but, generally, it is seen as a way to acquire a healthy balance between body, mind and spirit. It means the acquirement of a real and durable state of good. This concept sees an individual’s health as a whole. In this view, it offers a holistic vision on health. Not any kind of difference can be used as a differentiating element to design a strategy. Identifying and presenting the main differences that should mean advantages for the consumers are the topics of our paper. Drawing up the strategy for a spa-hotel competition we could take into consideration the repositioning, mentioning in the campaign the attributes that only the mentioned product it has. It is essential, to obtain a leader position on at least one attribute appreciated by the consumers. When the supremacy cannot be obtained, it is suggested the fourth strategy that of ‘the close club” (Ph. Kotler - 2000). The preliminary market research is presented and this is the preliminary step for drawing up the strategy.

Mihaela Constantinescu

RELATED PAPERS

elena untaru

Platforma/Laborator de Analize Statistice şi Previziune …

Iacob Catoiu , Monica M Coros

Maria Andrada Georgescu

Revista De Turism Studii Si Cercetari in Turism Journal of Tourism Studies and Research in Tourism

ELENA MATEI

Mazilu Mirela

Shivani Sharma

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences (PROSOC)

Daniel Serbanica

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF …

Petre Brezeanu

WSEAS Transactions On …

Georgiana Ciuchete

Sorin Mihai Radu

Gabriela Cecilia Stanciulescu

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PETROŞANI∼ ECONOMICS …

Sebastiano Patti

Annals of Faculty of Economics

Lisetchi Mihai

Andreea Ionica

Costea Ciprian

The Annals of the

Carmen Nastase

Carmen Emilia Chasovschi

The Annals of the Stefan Cel Mare University of Suceava Fascicle of the Faculty of Economics and Public Administration

Mariana Vlad

manuela gogonea

Irina Dragan

Mirela Danubianu , tiberiu socaciu

tiberiu socaciu

Albu Otilia

Annals of the Stefan cel Mare …

claudia moisa

Bogdan Dima

COORDONATORII REVISTEI, LUCRĂRI …

Elena Petrea

Annals of the Stefan cel Mare University of …

Catalin Lupu

The Annals of …

Daniela Calu , Madalina Dumitru

Puiu NISTOREANU

Nicolae Teodorescu

Liviu Popescu

COORDONATORII …

Iuliana Breaban

Deaconu Adela , Nistor Silvia

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Do destinations have multiple lifecycles?

Bob mckercher.

a School of Hotel and Tourism Management the Hong Kong Polytechnic University Hung Hong, Kowloon Hong Kong, SAR, China

IpKin Anthony Wong

b School of Tourism Management Sun Yat-Sen University, Tang Jia Wang, Xiangzhou, Zhuhai, China

This research note tests the proposition empirically that destinations have multiple lifecycles. It studies tourist arrivals to over 200 destination countries and economies over a 35 year period and applies Butler's parameters to map their lifecycles. Six different lifecycle patterns were identified. Empirical findings from this study echo's Baggio's conceptual notation by showcasing that destination lifecycles seems to follow specific traits commensurate with other destinations to form a typology of networked lifecycles. In other words, we go beyond the single-destination lifecycle paradigm to improvise a new research direction that centers on co-occurrence of destination changes that reflect a certain type of lifecycle. It paves the way by introducing the concept of destination coevolution as an analogy to describe lifecycle reciprocity among a cluster of destinations that undergo a similar evolutionary odyssey.

1. Introduction

Butler's (1980) Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model has been recognized as one of the core concepts in tourism. Developed from the product lifecycle model it, or more accurately the interpretation of it by most in the tourism community, implies strongly that destinations move through a single lifecycle from introduction, through growth, maturity and post maturity. The prevailing sentiment for the post maturity stage is a likely end in decline, abetted in part by Plog's (2001) assertion that destinations hold within them their own seeds of destruction. Butler suggested originally rejuvenation is possible but even he thinks it is a short term solution and that “without a complete change in the attractions on which tourism is based” ( Butler, 1980 , p. 9) destinations are unlikely to recover. Interpretation of the model by scholars endorses the singular lifecycle approach to such an extent that at its most crude, Butler's work is reduced to nothing more than an S-shaped curve.

But, the inherent subtly of this model is often overlooked for both the x (time) and y (volume of visitors) axes are open-ended. Moreover, five possible post maturity outcomes are identified including two growth scenarios, ongoing stability and two decline options. The title of the original paper, The Concept of a Tourism Area Cycle of Evolution , and the opening gambit that states "there can be little doubt that tourist areas are dynamic, that they evolve and change over time” ( Butler, 1980 , p. 5) are also instructive, for they suggest destination evolution is an ongoing process . Indeed, Bulter (2009) reasserted this opinion some 30 years later when he noted “to say that destinations evolve or change is a truism” (p. 248).

Although Butler's (1980 , 2009 ) work is seminal and informative in its own right, its articulation of TALC is largely based on conceptual improvisation without a strong empirical grounding that could generalize to all destinations. In fact, this stream of work has largely been discussed at a conceptual level. Agarwal (2006) , for example, argues some destinations progress through a reorientation stage before continuing on their evolutionary path. Prideaux (2000) has also modeled multiple destination lifecycles influenced by major infrastructure development that leads to the opening up of a destination to new markets and thus propelling it to a further growth stage. Weaver (2000) took a long term view and suggested destination evolution can be interrupted by war, with collapse and then recovery to a new phase. Garay and Cànoves (2011) integrate regulation theory to explain that a destination may experience multiple lifecycles through a restructuring process with stages of transformations. Ma and Hassink (2013) use evolutionary economic geography to help interpret the TALC model and to differentiate between lifecycle and evolution; and hence, a destination that experienced multiple lifecycles renders an evolutionary process.

Recent research sheds some light on TALC with evidence demonstrating both convergence and divergence to the S-shape distribution. For example, Kristjánsdótti (2016) investigated tourist inflow to Iceland and found an exponential growth correlated with economic and city development such as banks, roads, and the Internet. Garcia-Ayllon (2016) utilized GIS retrospective analysis to illustrate evolution of the landscape of La Manga, Spain through a panoramic view. The study concludes that a declining cycle of the resort was primarily a result of poor city planning and a second-home real estate market boom that ultimately led to overcrowding and a deterioration of the place's attractiveness. Garcia-Ayllon's investigation corroborates that of Kubickova and Martin (2020) , who found that destinations fall into different stages of TALC due to government involvement and market competitiveness. Singh (2020) , however, demonstrated how different destinations may deviate from the hypothetical S-curve based on environmental factors such as climate and geographic locations. In summary, deviation from Butler's TALC is often observed since destinations are not homogenous; rather they can be “conceptualised as a mosaic of elements, each of which can follow a lifecycle that is different from that of the destination overall” ( Chapman & Light, 2016 , p. 254).

The aforementioned challenges to TALC may reflect the fact that the model was an outgrowth of the Cartesian-Newtonian, systems thinking prevalent at the time, that saw systems as machines that should work in a predictable manner ( Faulkner & Russell, 1997 ). Since then, though complexity theory ( Baggio, 2008 ) has emerged as an alternative theoretical method to consider destination evolution. Complexity theory argues a destination may have multiple lifecycles, whereby an otherwise apparently stable system undergoes phase shift that pushes it into a new lifecycle phase.

This research note tests the proposition empirically that destinations have multiple lifecycles. That said, the contribution of this study lies not only in answering the question of whether or not destinations have multiple cycles, but also in reasoning why some destinations collude to have similar growth/decline trajectories. In essence, it aims to open a forum of new discussion on destination coevolution. It paves the way for a paradigm shift from a singular-cycle model to a symbiotic networked system of cyclical trajectories that coevolve to form a different typology of lifecycles that share similar evolutionary traits.

This study adhered to the six operational decisions of TALC proposed by Haywood (1986) . First, it used countries/territories as the unit of analysis through secondary data provided by the UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Second, the study utilizes time (y axis) and arrivals (x axis) to replicate Butler's original model ( Butler, 2011 ). Third, the data set covered the period 1984 to 2017. These data were gleaned from the UNWTO e-library for the period 1995 to 2017 and from various Compendiums of Tourism Statistics published by the UNWTO from 1984 to 1994. The data set was fairly complete, especially from 1995 onward. Some gaps exist prior to 1995, especially among Eastern European countries and former Soviet Union republics which did not gain their independence until after 1989.

Fourth, arrivals for international travel from a total of 202 countries and territories were analyzed. Although there are other units of measurement such as tourist expenditure and hotel bed capacity (e.g., Cole, 2012 ), most research published to date utilizes tourist arrivals as a proxy for lifecycle patterns ( Kubickova & Martin, 2020 ; Moore & Whitehall, 2005 ). This usage may be attributed to the fact that tourist arrivals reflect tourism demand and hence, the overall attractiveness and value of a place ( Garcia-Ayllon, 2016 ). Fifth, homogeneity was assumed for the relevant market. That is, international tourists were treated as a homogenous segment. Finally, pattern and stages as well as shape of TALC for each specific region were investigated, while categorization was undertaken to better discern lifecycle patterns. In particular, arrivals for each specific country/territory over the 34-year period of analysis were depicted for visual examination, as the figures below illustrate. Phase delineation was based on a visual analysis of the data, coupled with analysis of a two year rolling average of arrivals to control for unique anomalies, such as the impact of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) event of 2003.

2.1. Do destinations have multiple lifecycles?

Do destinations evolve through multiple lifecycles? The short answer is yes, as 162 of the 202 countries and territories studied displayed such patterns. Six different styles were observed. Table 1 identifies each and describes the number of economies displaying each pattern, the median number of discrete lifecycles and the median number of lifecycle stages observed, plus the median number of years per lifecycle and lifecycle stage. Butler's model represents a visual metaphor for the evolution of destinations. The interpretation presented below is also shown visually to emphasise the different types of lifecycles the destinations evolve through. Exemplars of each type are shown below.

Summary of TALC categories.

Four Pacific island nations could still be classified as being in the exploration phase of their lifecycle, even after 34 years of monitoring. They include Niue, the Marshall Island, Kiribati and Tuvalu. Each attracted 10,000 or fewer tourists a year, with little change noted in arrivals over the entire 34-year study frame. Tuvalu is shown as the example ( Fig. 1 a). This country attracted fewer than 2000 tourists up to 2008 and has never attracted more than 3000 a year since then. These island nations are located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and are distanced away from the mainland of Asia, the Americas, and Australia. These paradise-like locales are small in land area and have limited tourism products.

Categories of lifecycle.

Another 20 destinations have enjoyed a single, unbridled period of growth. They typically progressed through long exploration and discovery phases before visitor numbers rise exponentially. The growth spurt has slowed occasionally, but the trend has been largely upward. Destinations in this cohort recorded the longest duration of individual stages. A total of eight of 20 countries are in Asia, with another five located in Africa. Interestingly, all but Taiwan, Iceland and Japan can be considered as emerging economies or post Soviet economies. Iceland ( Fig. 1 b) is an exemplar. It progressed through an almost 15-year exploration phase before starting to generate more arrivals in the early 2000s. Growth rates have accelerated since about 2011. As most of the regions are still developing their economies, the same goes for their tourism products. Therefore, the exponential growth of these places may partly be attributed to opportunities availed from regional development and hence, better accessibility and infrastructure for inbound tourists. Likewise, development of tourism infrastructure may also foster outbound travel.

By contrast, three destinations appear to be in long-term decline. Two are in the Caribbean and one in Europe and include Montserrat, Bermuda and Liechtenstein. Here the pattern tends to be scallop shaped, suggesting a reorientation, but trending downward. While there are occasional rebounds in arrivals, the long-term trend is decline. Such destinations progress through multiple discrete lifecycles, each lasting a median of about nine years, with each phase lasting a median of four years. However, the rebound phase is short, while the decline phase is much longer. Bermuda ( Fig. 1 c) is a case in point. Its arrivals peaked in 1987. Since then it has evolved through a series of four discrete lifecycles, with each ending with a drop in arrivals. It is now in its fifth phase, showing a modest growth in arrivals since 2015. These destinations represent mini nations that are mostly adjacent to popular world resort locations such as Switzerland and Puerto Rico (both exhibit a full-cycle pattern).

Conversely, 85 countries and territories displayed a scalloped-shaped growth lifecycle pattern. Here, the re-orientation period is short and has led to a revitalisation of the region. Each destination has moved through between two and five discrete lifecycles, with each one lasting about 12 years. They also move through a large number of stages, lasting about five years each. The pattern displayed by the Netherlands ( Fig. 1 d) is typical. While all regions are represented by this pattern, it is most common in European destinations (25 of the 47 European countries), the Americas (14 of 20 countries) and Pacific island nations (12 of 25 countries) while being less common in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. This cluster is typified by large economies, such as the US, China, Germany, France, and Brazil, as well as territories that are situated near them. With a few exceptions, correlations among arrivals of these locales are generally high, with significance at or above the .05 level. Their correlations may imply that rise and fall of their inbound travel demands are not isolated instances, but are dependent on the fluctuations of nearby economies.

Another 77 destinations display a more complete multi-lifecycle evolutionary pattern, including a substantial period of decline before rebounding to new periods of growth. Here the reoirentation period is rather traumatic. The case of Monaco is typical ( Fig. 1 e). It has progressed through at least three discrete lifecycles and is in the midst of a fourth one. Destinations that display this pattern are typfied by periods of strong growth, followed by periods of equally strong decline. While the overall trend is upward, they have also suffered through multiple years of declines in arrivals. This type of pattern is most likely to been seen in European (17 cases), African (16 cases) and Caribbean nations (13). They are typified by small to medium sized nations. With a few exceptions such as Switzerland, Egypt, and South Korea, most of them do not have a strong presence in tourism. These locales are dominated by developing/underdeveloped economies that have yet to develop a full range of tourism infrastructure and products. Similar to the scalloped-shaped growth cluster, correlations of tourist arrivals among these places are generally high and signficant at the .05 level, suggesting that their lifecycles are not independent.

Lastly, 13 destinations displayed highly volatile lifecycle patterns that defy easy categorization. More than half are located in Africa. The Gambia is a typical example ( Fig. 1 f). None of these destinations ever entered a period of stability and none displayed any consistent pattern. Instead, each is typified by a series of messy lifecycles, short duration stages and rapidly changing patterns of growth and decline. These locales are typified by small developing/underdeveloped economies that have yet to support a full range of tourism products and hence, represent unrealized market potential for tourism. Interestingly, these regions are situated near the equator with a rather warm climate.

3. Discussion and conclusions

The findings support the core proposition espoused by Butler that destinations are dynamic entities that change over time. It also supports the inherent, but often overlooked ingenuity of his model whereby both axes are open ended. In doing so, the findings challenge the often misinterpreted conclusion that destinations have single lifecycles. Instead, Butler's model best depicts individual, discrete lifecycle phases that can then be aggregated to reflect the overall evolution of a destination economy. And so, the study essentially provides empirical evidence in support of Butler's model. Importantly, though it extends the model to appreciate the inbuilt volatility inherent in destinations.

Destination lifecycle is a visual metaphor that vividly delineates fluctuations of tourist demand over time. Butler's (1980) work provides clear conceptual guidance on how a place may evolve. Empirical evidence collated from this study suggests that destination evolution does occur and that by and large, destinations evolve through multiple cycles. These symbiotic cyclic patterns can further be classified into six major categories with each sharing similar evolutionary traits. This study reconciles the divide between the one-size-fits-all single-cycle model and the destination mosaic in which “each [place] can follow a lifecycle that is different from that of the destination overall” ( Chapman & Light, 2016 , p. 254). This discovery is rather salient to the lifecycle studies, as the body of literature has largely acknowledged that “a destination can be seen as a system composed by a number … of elements that share some kind of relationship. The system evolves by responding to external and internal inputs. It may well be considered as a complex adaptive system” ( Baggio, 2008 , p. 3). This fundamental premise lays the necessary foundation of tourism through the lens of complexity theory that underlies systems thinking. Yet, this foundational conceptualization of the tourism system is often based on the singularity of a specific destination ( Chapman & Light, 2016 ; Garcia-Ayllon, 2016 ; Singh, 2020 ) without considering the broader ecosystem at a regional or even global scale.

As Baggio (2008) asserts, “Most complex systems can be described as networks of interacting elements. In many cases these interactions lead to global behaviors that are not observable at the level of the single elements and that share the characteristics of emergence typical of a complex system … the collective properties of dynamic systems composed of a large number of interconnected parts are strongly influenced by the typology of the connecting network” (p. 8). Empirical findings from this study echo's Baggio's conceptual notation by showcasing that destination lifecycles seems to follow specific traits commensurate with other destinations to form a typology of networked lifecycles. In other words, we go beyond the single-destination lifecycle paradigm, which focuses on cycles, sub-cycles, and even super-cycles ( Singh, 2020 ) of one resort, to improvise a new research direction that centers on co-occurrence of destination changes that reflect a certain type of lifecycle.

Although we did not test any network assumptions, this study nevertheless provides early evidence that can pave the way for gaining a deeper understanding of why some destinations evolve similarly. The typology of destination lifecycles points to an important but seldom recognized phenomenon, the coevolution of destinations. Coevolution is a phenomenon commonly observed in biology to describe multiple species' evolutionary journeys; they are correlated, in that one's evolution affects the other. Our empirical findings illuminate this phenomenon in the tourism context, in that a destination's progress and decline is not an isolated instance. Rather, its lifecycle falls into a pattern that resonates closely with other destinations, especially those in proximity (e.g., small Pacific island nations that undergo exploration and a number of Asian/European regions experienced radical growth). In other words, a destination may evolve a trait (i.e., progression or decline) in reciprocity with the same trait in others, especially destinations that are geographically close.

Also, similar to the ideas mooted in complexity theory, two primary destination lifecycle categories (i.e., scalloped growth and full cycles) stand out to dominate the destination eco-system. While these two forms of lifecycles only seem to deviate based on the volatility of each cycle—perhaps attributed to how each category of destination interacts with the broader tourism environment, in general, destinations do have multiple cycles and they seem to mutate from Butler's “singular” lifecycle model. To this end, this study sheds new light on the research area not only by demonstrating that destinations encounter various lifecycles, but by introducing the concept of destination coevolution as an analogy to describe lifecycle reciprocity among a cluster of destinations that undergo a similar evolutionary odyssey.

By showcasing that destinations do evolve and coevolve in multi-cyclic trajectories, this study hints at plausible conditions, such as globalization, crisis, and changes in tourist behaviors, associated with transformation to a broader ecosystem that may ultimately bring temporary or long-lasting effects to destinations. Although the exact cause of such impacts may require further investigation, they open a window of opportunity for future research. First, as fluctuations of lifecycles are not isolated instances, concerns arise as to why destinations coevolve. The underlying mechanism may hint at different forms of coevolution. For instance, the emergence of major world economies and travel outbound source markets, such as the US, European Union nations, Japan, China, and other BIRCS countries, have bought seismic changes to the travel ecosystem and helped to cultivate a wide array of popular travel destinations that heavily rely on these origins. Such a host–parasite coevolutionary relationship may help to explain why the rise and fall of a major economy (e.g., Japan and China) could ultimately affect certain destination clusters (e.g., Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, Fiji, and Hong Kong) that heavily rely on such a host. This phenomenon also relates to a second future research stream that points to stability and volatility of destinations. This line of inquiry may add to McKercher and Mak's (2020) concept of destination health/risk to better explain why certain markets/market clusters are more (vs. less) valuable to others. As COVID-19 brought immense devastations to the travel industry, it is time to reframe our understanding of TALC to adhere to a more systems thinking approach in seeking means for destinations to co-adapt to the “new normal” under this unprecedented global pandemic.

3.1. Research limitations and future research

This research follows the tradition in assessing TALC by drawing data from tourist arrivals. Although there may still be debate on what constitute a lifecycle, most researchers believe that what we have demonstrated in this investigation goes beyond a cycle and points to the evolution of destinations ( Chapman & Light, 2016 ; Garcia-Ayllon, 2016 ; Kristjánsdóttir, 2016 ; Ma & Hassink, 2013 ; Singh, 2020 ). This research, however, moves beyond the concept of evolution to lay the grounding for future research on destination coevolution. It does so by heeding the call from Singh (2020 , p. 1) that “a theory of evolution is necessary to understand tourism … unless a fresh perspective on time is considered.” The real question for future inquiry, however, should not be centered on the distinction of lifecycle versus evolution; rather new insights should be sought for why some destinations follow similar growth trajectories, while others do not. As scholars delve further into the coevolutionary stream of work, we hope to see that the TALC model is not simply a two-dimensional model that is determined by x (time) and y (volume), but also by z (space or other spatial locales). Here, the model could be rendered in three dimensions, or in two dimensions with the third aspect (z) to reflect fluctuation of a destination relative to other locales. 1 It would also be interesting for future studies to consider both the causes of coevolution as well as destination ties to better understand the centrality, for example, of the broader networked ecosystem.

Impact statement

This research note tests the proposition empirically that destinations have multiple lifecycles. The findings support the core proposition espoused by Butler that destinations are dynamic entities that change over time. It also supports the inherent, but often overlooked ingenuity of his model whereby both axes are open ended. In doing so, the findings challenge the often misinterpreted conclusion that destinations have single lifecycles. Its contribution lies in reasoning why some destinations collude to have similar growth/decline trajectories. In essence, it aims to open a forum of new discussion on destination coevolution as an analogy to describe lifecycle reciprocity among a cluster of destinations that undergo a similar evolutionary odyssey.

Declaration of competing interest

Biographies.

Bob McKercher ([email protected]) is a professor in The Hong Kong Polytechnic University's School of Hotel and Tourism Management. He has wide ranging research interests. He received his PhD from the University of Melbourne in Australia, a Masters degree from Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada and his undergraduate degree from York University in Toronto, Canada.

IpKin Anthony Wong ([email protected]) is a professor at Sun Yat-Sen University, China. He has a wide range of teaching and research interests especially in tourist motivation and behaviors, consumer behaviors, tourism and service marketing, casino gaming, and research methods. He is currently serving as an advisory board member for leading tourism and hospitality journals including Journal of Travel Research, International Journal of Hospitality Management, and Journal of Business Research.

1 For a detailed description of changes of actors in a social network, see Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson (2018) .

- Agarwal S. The anatomy of the rejuvenation stage of the TALC. In: Butler R., editor. Tourism area Life cycle Vol 2: Conceptual and theoretical issues. Channel View Publications; Clevendon: 2006. pp. 183–200. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baggio R. Symptoms of complexity in a tourism system. Tourism Analysis. 2008; 13 (1):1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borgatti S.P., Everett M.G., Johnson J.C. 2 ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks CA: 2018. Analysing social networks. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer. 1980; 24 :5–12. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler R.W. Tourism destination development: Cycles and forces, myths and realities. Tourism Recreation Research. 2009; 34 (3):247–254. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler R. Goodfellow Publishers; 2011. Tourism area lifecycle. Contemporary tourism reviews. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chapman A., Light D. Exploring the tourist destination as a mosaic: The alternative lifecycles of the seaside amusement arcade sector in Britain. Tourism Management. 2016; 52 :254–263. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole S. Synergy and congestion in the tourist destination life cycle. Tourism Management. 2012; 33 (5):1128–1140. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faulkner B., Russell R. Chaos and complexity in tourism: In search of a new perspective. Pacific Tourism Review. 1997; 1 (2):93–102. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garay L., Cànoves G. Life cycles, stages and tourism history: The Catalonia (Spain) experience. Annals of Tourism Research. 2011; 38 (2):651–671. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia-Ayllon S. Geographic information system (GIS) analysis of impacts in the tourism area life cycle (TALC) of a Mediterranean resort. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2016; 18 (2):186–196. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haywood K.M. Can the tourist-area life cycle be made operational? Tourism Management. 1986; 7 (3):154–167. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kristjánsdóttir H. Can the Butler's tourist area cycle of evolution be applied to find the maximum tourism level? A comparison of Norway and Iceland to other OECD countries. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism. 2016; 16 (1):61–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kubickova M., Martin D. Exploring the relationship between government and destination competitiveness: The TALC model perspective. Tourism Management. 2020; 78 :104040. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ma M., Hassink R. An evolutionary perspective on tourism area development. Annals of Tourism Research. 2013; 41 :89–109. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKercher B., Mak B. Identifying destination health: Developing the concepts of market indifference and destination dependence/market irrelevance. Journal of Travel Research. 2020; 59 (5):879–892. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore W., Whitehall P. The tourism area lifecycle and regime switching models. Annals of Tourism Research. 2005; 32 (1):112–126. [ Google Scholar ]

- Plog S. Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 2001; 42 (3):13–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- Prideaux B. The resort development spectrum — a new approach to modeling resort development. Tourism Management. 2000; 21 (3):225–240. [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh S. Time, tourism area ‘life-cycle,’ evolution and heritage. Journal of Heritage Tourism. 2020:1–12. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weaver D.B. The exploratory war-distorted destination life cycle. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2000; 2 (3):151–161. [ Google Scholar ]

Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research II pp 271–285 Cite as

Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) and the Quality of Life (QOL) of Destination Community Revisited

- Muzaffer Uysal 11 ,

- Eunju Woo 12 &

- Manisha Singal 13

- First Online: 24 September 2023

268 Accesses

Part of the book series: International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life ((IHQL))

This chapter examines the connection between the tourism (TALC) and its effects on the quality of life (QOL) of destination communities. We posit that as destinations go through structural changes over time, the extent to which the dynamics of change affect the QOL of the resident community vary with the stages of the life cycle. The chapter consists of four major sections. After a brief introduction, the first section presents the concept of TALC and describes the development phases and the indicators that help understand tourism area development. The second section provides a brief discussion on the impact of tourism on the community in relation to TALC, which is then followed by the third section which focuses on the adjustment to change and maintaining the QOL of the community. Section four reviews the literature to support the relation between TALC and QOL of communities. The chapter ends with describing critical issues for future research, outlining some of the difficulties moving forward, and formulating relevant policy implications that may help the researchers and destination management organizations to further examine important issues that surround TALC and QOL connections.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Akis, S., Peristianis, N., & Warner, J. (1996). Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: The case of Cyprus. Tourism Management, 17 (7), 481–494.

Article Google Scholar

Allen, L. R., Hafer, H. R., Long, P. T., & Perdue, R. R. (1993). Rural resident attitudes toward recreation and tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 31 (4), 27–33.

Allen, L. R., Long, P. T., Perdue, R. R., & Kieselbach, S. (1988). The impacts of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. Journal of Travel Research, 26 (1), 16–21.

Andereck, K. L. (1995). Environmental consequences of tourism: A review of recent research. In Linking tourism, the environment, and sustainability. Annual meeting of the national recreation and park association (pp. 77–81).

Google Scholar

Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research, 39 , 27–36.

Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impact. Annals of Tourism Research, 19 , 665–690.

Bachleitner, R., & Zins, A. H. (1999). Cultural tourism in rural communities: The residents’ perspective. Journal of Business Research, 44 , 199–209.

Beardsley, M. E. G. H. A. N. (2016). Quality of life, the tourism area life cycle and sustainability: A case of Cuba. In Sustainable island tourism: Competitiveness and Quality of Life (pp. 93–105). CAB International.

Chapter Google Scholar

Berbekova, A., Uysal, M., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). Toward an assessment of quality of life indicators as measures of destination performance. Journal of Travel Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211026755

Birsen, A. G., & Bilim, Y. (2019). A comparative life cycle analysis of two mass tourism destinations in Turkey. Journal of Tourism and Gastronomy Studies, 1290 , 1313.

Boyd, S. W. (2006). The TALC model and its application to national parks: A Canadian example. In C. Cooper, C. M. Hall, & D. Timothy (Series Eds.), & R. W. Butler (Vol. Ed.), The tourism area life cycle: Vol. 1. Applications and modifications (pp. 119–138). Channel View Publications.

Brunt, P., & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 26 , 493–515.

Budruk, M., & Phillips, R. (2011). Quality of life community indicators for parks recreation and tourism management . Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourism areas cycle of evaluation: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24 (1), 5–12.

Butler, R. W. (2004). The tourism area lifecycle in the twenty first century. In A. A. Lew, Butler, R. W. (Eds.). (2006). The tourism area life cycle (vol. 1). Channel view publications.

Cornell, D. A. V., Tugade, L. O., & De Sagun, R. (2019). Tourism quality of life (TQOL) and local residents’ attitudes towards tourism development in Sagada. Philippines. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 31 , 9–34.

Diedrich, A., & Garcia-Buades, E. (2009). Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tourism Management, 30 , 512–521.

Doğan, Z. H. (1989). Forms of adjustment: Sociocultural impacts of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 16 , 216–236.

Doğan, Z. H. (2004). Turizmin Sosyo-Kültürel Temelleri . Detay Yayıncılık.

Doxey, G. V. (1976). When e nough’s enough : The natives are restless in old Niagara. Heritage Canada, 2 (2), 26–27.

England, J. L., & Albrecht, S. L. (1984). Boomtowns and social disruption. Rural Sociology, 49 , 230–246.

Formica, S., & Uysal, M. (1996). The revitalization of Italy as a tourist destination. Tourism Management, 17 (5), 323–331.

Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (1), 79–105.

Haralambopoulos, N., & Pizam, A. (1996). Perceived impacts of tourism: The case of Samos. Annals of Tourism Research, 23 , 503–526.

Haywood, K. M. (1986). Can the tourist-area lifecycle be made operational? Tourism Management, 7 (3), 154–167.

Hovinen, G. R. (2002). Revisiting the destination model. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (1), 209–230.

Hu, R., Li, G., Liu, A., & Chen, J. L. (2022). Emerging research trends on residents’ quality of life in the context of tourism development. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 10963480221081382 , 109634802210813.

Johnson, J. D., & Snepenger, D. J. (1993). Application of the tourism life cycle concept in the greater Yellowstone region. Journal of Society & Natural Resources, 6 (2), 127–148.

Johnson, J. D., Snepenger, D. J., & Akis, S. (1994). Residents’ perceptions of tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 21 (3), 629–642.

Jurowski, C., & Brown, D. O. (2001). A comparative of the views of involved versus noninvolved citizens on quality of life and tourism development issues. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 25 (4), 355–370.

Jurowski, C., Daniels, M., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2006). The distribution of tourism benefits. In G. Jennings & N. P. Nickerson (Eds.), Quality tourism experiences (pp. 192–207). Elsevier.

Juvan, E., Podovšovnik, E., Lesjak, M., & Jurgec, J. (2021). A Destination’s social sustainability: Linking tourism development to residents’ quality of life. Academica Turistica-Tourism and Innovation Journal, 14 (1), 39–52.

Kim, H., Kim, Y. G., & Woo, E. (2021). Examining the impacts of touristification on quality of life (QOL): The application of the bottom-up spillover theory. The Service Industries Journal, 41 (11–12), 787–802.

Kim, K., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, J. (2003, June). The effects of tourism impacts upon quality of life of residents in the community. TTRA’s 34 th Annual Conference Proceedings, pp. 16–20. St. Louis, MO, USA.

Ko, D., & Stewart, W. P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Management, 23 , 521–530.

Krannich, R. S., Berry, E. H., & Greider, T. (1989). Fear of crime in rapidly changing rural communities: A longitudinal analysis. Rural Sociology, 54 , 195–212.

Liu, J. C., & Var, T. (1986). Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research, 13 (2), 193–214.

Long, P. T., Perdue, R., & Allen, L. (1990). Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes by community level of tourism. Journal Travel Research, 28 , 3–9.

McCool, S., & Martin, S. (1994). Community attachment and attitudes towards tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 32 (3), 29–34.

Meng, F., Li, X., & Uysal, M. (2010). Tourism development and regional quality of life: The case of China. Journal of China Tourism Research, 6 , 164–182.

Modica, P., & Uysal, M. (Eds.). (2016). Sustainable Island tourism: Competitiveness and quality of life . CABI.

Mok, C., Slater, B., & Cheung, V. (1991). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Hong Kong. Journal of Hospitality Management, 10 , 289–293.

Odum, C. J. (2020). The implication of TALC to tourism planning and development in the global south: Examples from Nigeria. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 8 (2), 68–86.

Oliveros Ocampo, C. A., Virgen Aguilar, C. R., & Chávez Dagostino, R. M. (2019). Approaches of research on the life cycle of the tourist area. Turismo y Sociedad, 24 , 51–75.

Oppermann, M. (1998). What is new with the resort cycle? Tourism Management, 19 (2), 179–180.

Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Allen, L. R. (1990). Resident support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 17 (4), 586–599.

Perdue, R. P., Long, P. T., & Kang, Y. S. (1999). Boomtown tourism and resident quality of life: The marketing of gaming to host community residents. Journal of Business Research, 44 , 165–177.

Peters, M., & Schuckert, M. (2014). Tourism entrepreneurs’ perception of quality of life: An explorative study. Tourism Analysis, 19 (6), 731–740.

Petrevska, B., & Collins-Kreiner, N. (2017). A double life cycle: Determining tourism development in Macedonia. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 15 (4), 319–338.

Pizam, A., & Pokela, J. (1985). The perceived impacts of casino gambling on a community. Annals of Tourism Research, 12 , 147–165.

Powers, T. M. (1988). The economic pursuit of quality . M. E. Sharpe.

Ramkissoon, H. (2016). Place satisfaction, place attachment and quality of life: Development of conceptual framework for Island destinations (pp. 106–116). Competitiveness and Quality of Life.