Visit Agenda

Agenda writing can be very demanding but worthwhile at the same time. It may easily guide participants on where to go and what to do at a given time period. It gives an insight on what must be accomplished within the time allotted to ensure that participants remain well-informed at all times. Because of such, it must be created well enough to serve its purpose.

In creating an effective meeting agenda , key points need to be discussed clearly. But to create an effective visit agenda, other matters must be focused on for it to run smoothly.

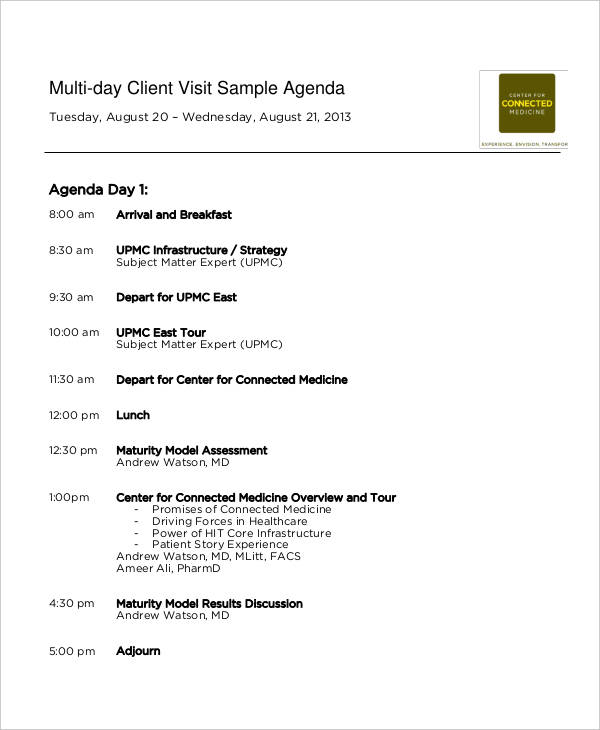

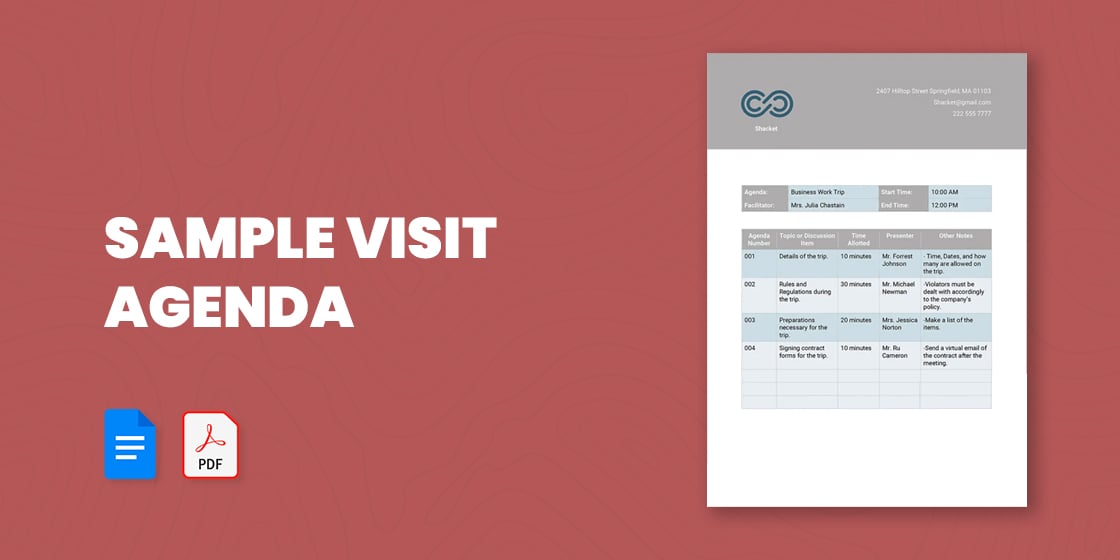

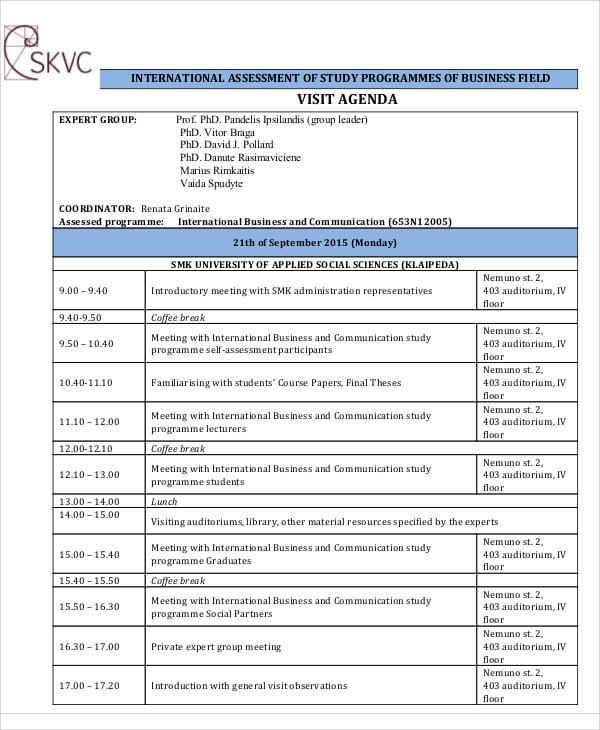

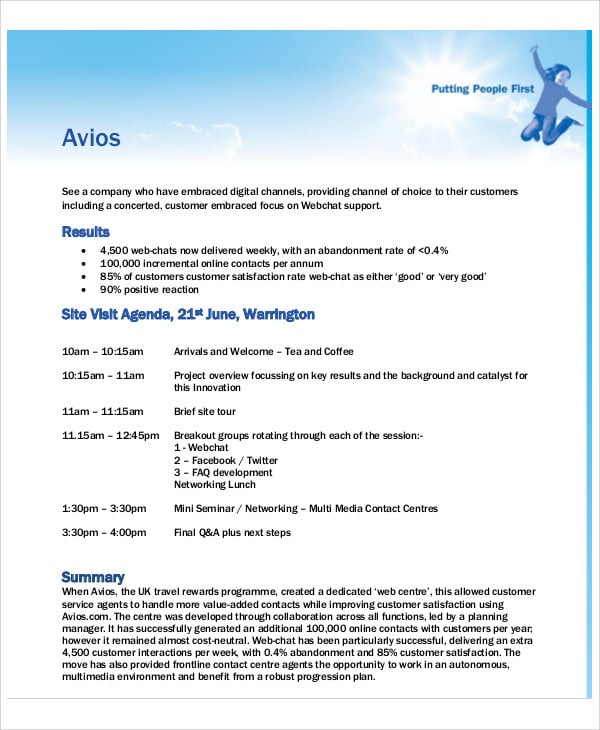

Client Visit Sample Agenda

Size: 158 kB

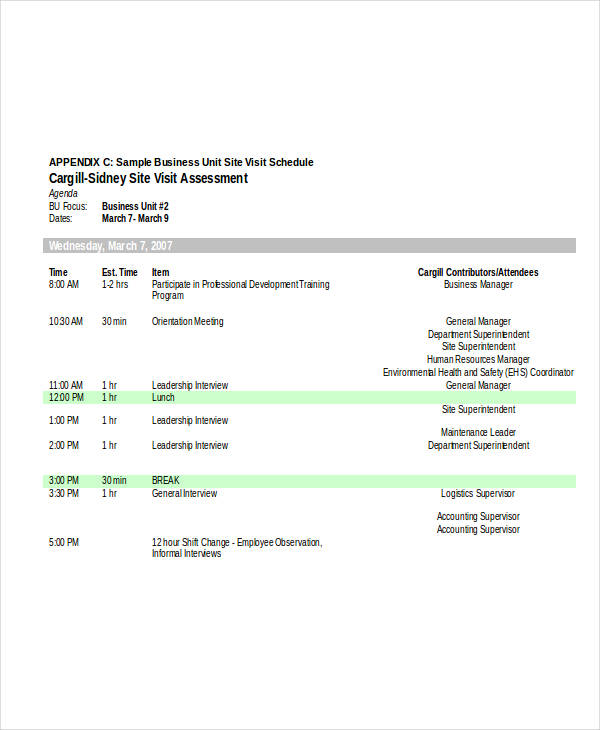

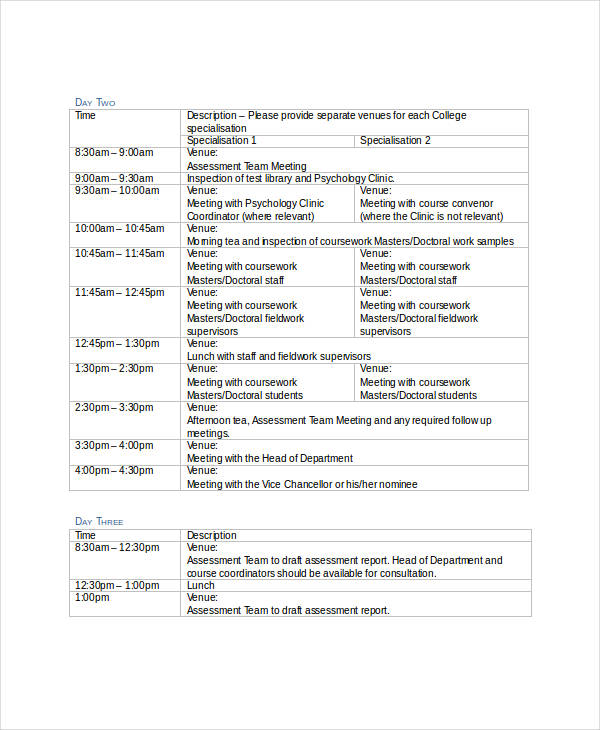

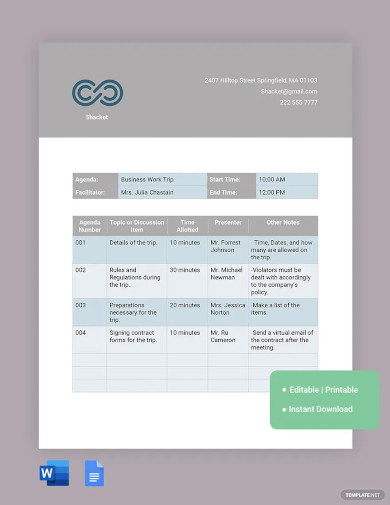

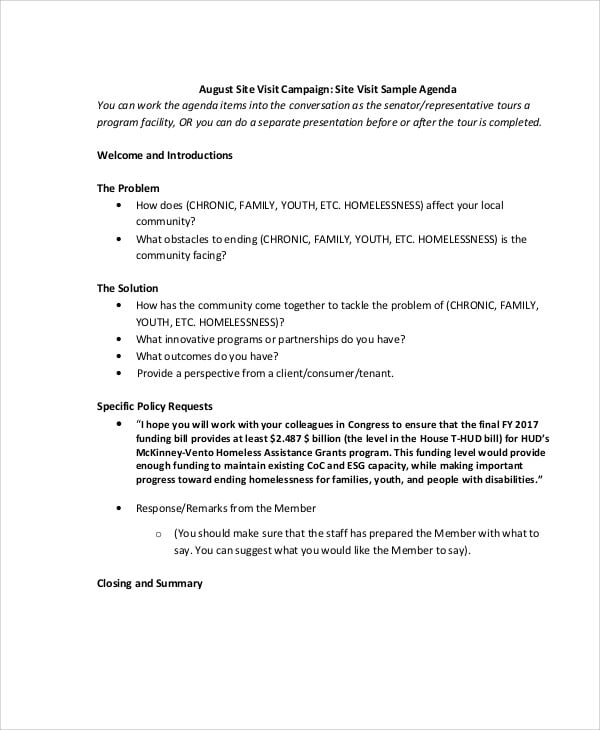

Business Visit Schedule Agenda

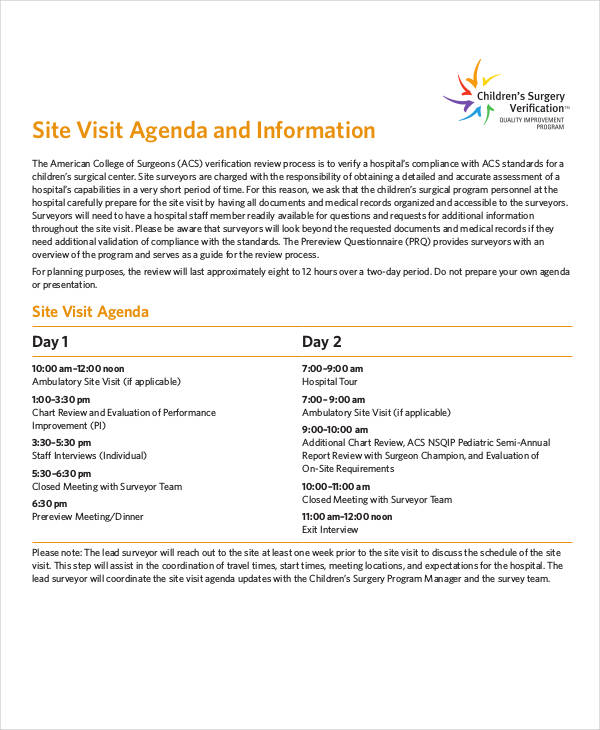

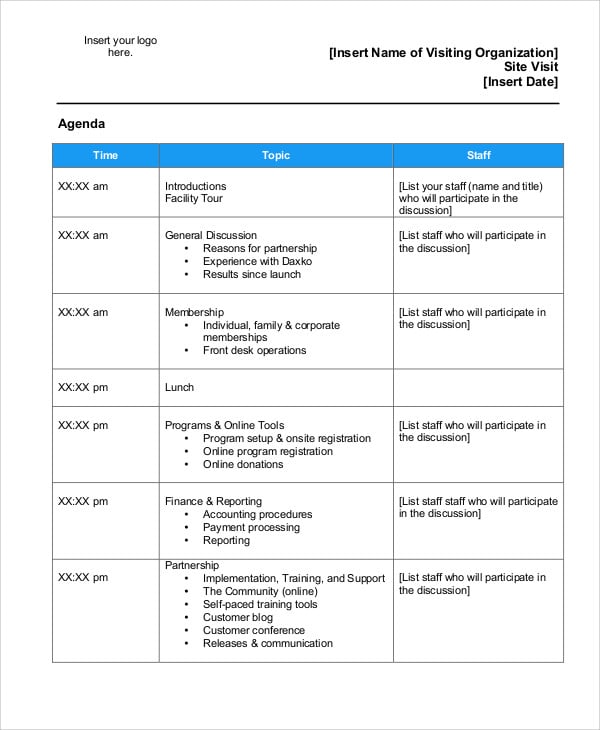

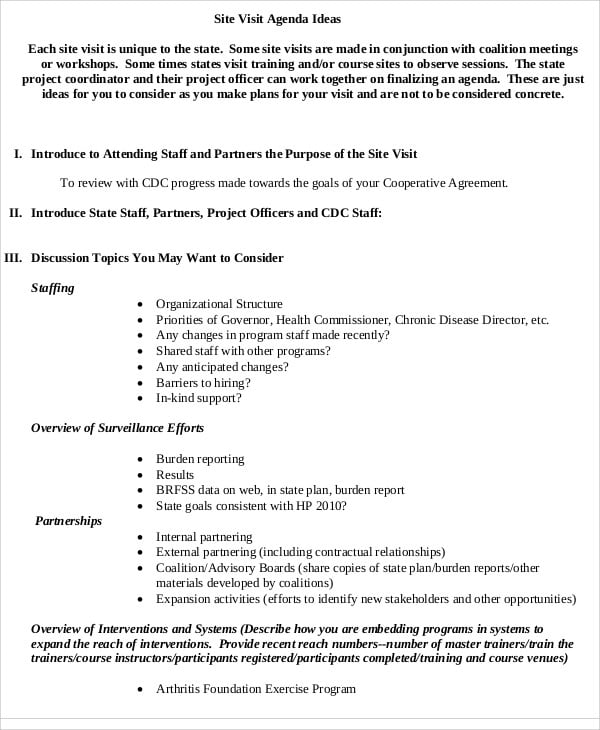

Site Visit Agenda and Information

Size: 451 kB

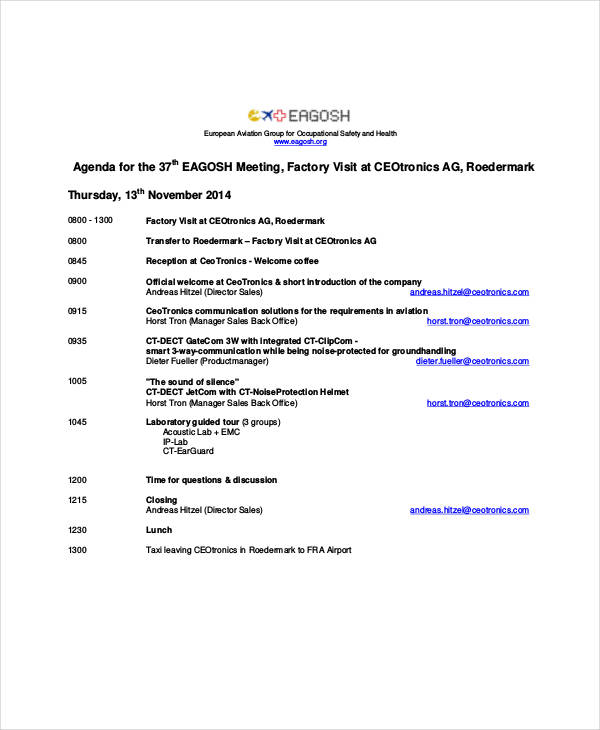

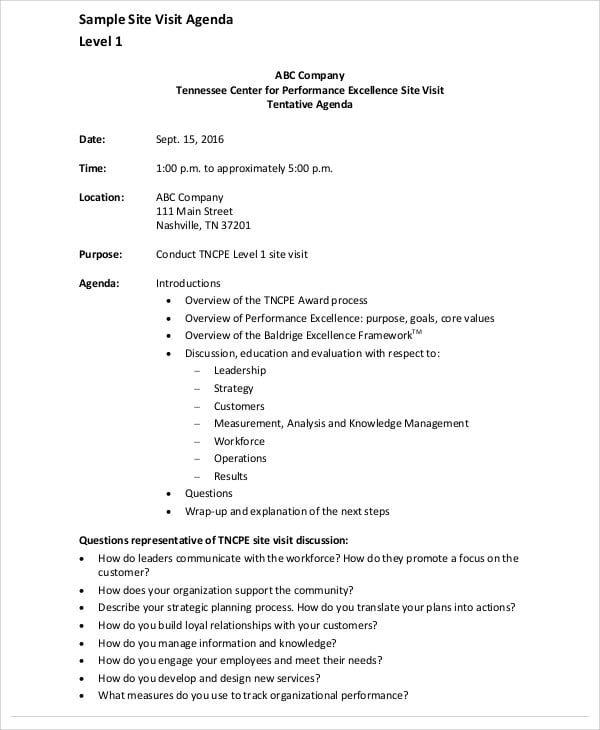

Factory Visit Agenda

Size: 30 kB

What Is a Visit Agenda?

A visit agenda and an itinerary is often used interchangeably. An agenda is a list of things to be done, such as a meeting of topics and issues to be discussed. There are multiple agenda examples that support this thought. An itinerary, on the other hand, focuses on the things to be done on a trip and other significant details of a particular location. A visit agenda is a strict list of details and instructions made for formal visits that are under a tight schedule.

How to Write a Visit Agenda

There are multiple agenda examples in excel that you can follow. But if you want to start from scratch, there are things to consider in writing a visit agenda.

The agenda must contain all the necessary details and instructions. From the participants involved to the given time period, even the smallest details are essential to carry it out. The agenda’s title should also provide a clear message to its readers, containing a proper insight of what the printable agenda is for. The details of the visit must also be well organized. Travel time might affect the next activity, so you must be practical when setting each activity.

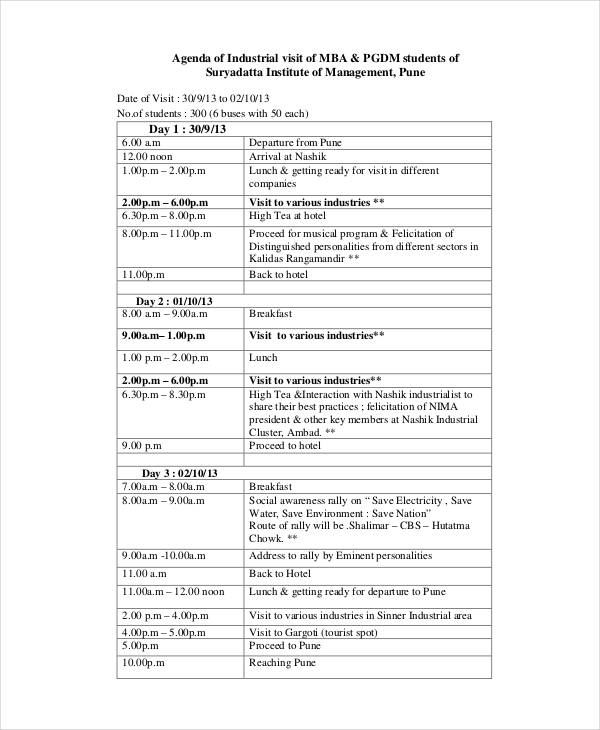

Agenda of Industrial Visit

Sales Agenda Sample

Guidelines for a Visit Agenda

To prepare a visit agenda, you need to know what needs to be covered within a given time period. These are the essential parts of the visit that have to be accomplished. If you wish to include an activity on the list, the details on how to achieve it must be thought through. This would include transportation and other essential materials. You may also see agenda examples in word to serve as your guide.

We often see tips on meeting agenda examples on how to make an effective agenda. A visit agenda is no different however, there are some guidelines that you should consider for a good visit agenda:

- Estimated time schedule. Although a schedule can alter due to unforeseen circumstances, it’s good to prepare a time frame for each activity to carry out smoothly.

- Start and finish. Although it’s not necessary to end the day formally, it’s a good idea to indicate the start and end of the agenda properly.

- Additional notes. These could be instructions on how to carry out activities.

- Update regularly. Changes in schedule or activities must be reflected immediately to avoid any form of conflict.

Agenda Maker

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Draft an agenda for the upcoming student council meeting focusing on school safety improvements and fundraising ideas

Create an agenda for a parent-teacher association meeting discussing new teaching methods and school year planning.

How to Plan the Perfect Customer Visit [+ Agenda Template]

Published: August 02, 2021

Now that the world is opening back up, it’s time to get out there and meet your customers face-to-face. For many newer customers, this might be their first time getting to spend time with you — especially as conferences have moved online.

Creating that connection is invaluable. But before you book that plane ticket, it’s essential to create a plan. Planning the perfect customer visit will ensure that you meet your goals and that your customer meeting will be successful. Here’s a look at how you get there.

![visit agenda meaning → Free Download: 61 Templates to Help You Put the Customer First [Download Now]](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/53/a66c79d4-2a39-46e6-a80a-f7b999133c06.png)

Why plan a customer visit?

Jason Lemkin, the founder of SaaStr and EchoSign, has said “ I never lost a customer I actually visited. ” That’s a bold statement — one that's worth taking note of. But why? What is it about customer visits that has such a big impact on customer loyalty?

First of all, you get to make a stronger impression with your customers. No matter what you sell, you aren’t just selling a product — you’re also selling the people behind it.

Your vision, your passion, your knowledge are all play into the perceived value of your product or service. All of these elements come across more strongly when you visit in person. A Zoom call just isn’t enough time to go deep.

Secondly, you get to see how your customers are using your product in person. Are they constantly printing out reports to pin up on a wall? Are you seeing teams walk across the sales floor to point out something on a screen? What kind of working environment and equipment do they have? What other types of software are they using?

Everything happening behind the scenes paints a much clearer picture of who your customers are. And when it comes time to renew or jump on that next customer success call, you’ll have a lot more knowledge ready to draw on.

Finally, meeting your customers in person is a huge motivational boost! When you’re behind a screen for so long, it can start to feel like what you do doesn’t matter — or that you’re not making any real connections. But a visit to a customer’s office can change all that, and really light up your idea of “why” you do this at all.

.png)

61 Templates to Help You Put the Customer First

Email, survey, and buyer persona templates to help you engage and delight your customers

- 6 buyer persona templates

- 5 customer satisfaction survey templates

- 50 customer email templates

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

5 Potential Goals of Your Customer Visit

Going into a customer visit with goals in mind will help you get the most out of your time there. Here are five goals to consider when planning a customer visit:

1. Understanding Their Business Goals

If you’re visiting a client, you’re likely hoping for a long term relationship. Understanding what their future goals are can help align your product with their needs. These in-depth conversations would rarely come up over a quick phone call.

2. Gathering Feedback

Customer visits provide a unique opportunity to gather honest and in-the-moment insight into what your customers need and want. When you sit next to someone who uses your product in their daily work, there’s a lot more space to have this feedback arise. And documenting it for future sales opportunities and your product team is one of the more productive actions you can take during a customer visit.

3. Referrals

In-person visits are a great time to ask for and give referrals. Ask, “Are there any other companies that you work with that you could see our product being helpful for?” Alternatively, if a pain point is mentioned by the client and you know the perfect company to help solve it, don’t be afraid to build that connection. It’s just another way you can bring value to your customers.

4. Uncovering Opportunities for Cross-Selling or Upselling

While your primary objective shouldn’t be pitching your offering at every opportunity, you might uncover a problem that your product or service can help solve. Noting these potential value-adds can make for more effective, thoughtfully targeted upsell and cross-sell conversations.

5. Testimonials and Case Studies

Customer visits can be a unique source of sales content, including pictures for case studies, video testimonials, and strong evidence-based customer stories. If you plan on making this one of your primary goals, consider asking your client to set the stage for these kinds of materials before you visit so you already know who you’ll be speaking to, before coming onsite.

How to Plan an Onsite Customer Meeting

By putting more effort in before you go, you’ll have a much better chance of achieving your goals and impressing your clients. Here are some key actions to consider when planning your customer meeting.

Thoroughly prepare before the visit.

Before you arrive, make sure you’re up to date on the state of the customer's account. Who are they usually talking to at your company? What customer service tickets have they raised lately? Are there outstanding issues that need to be addressed? These will come up during your visit.

Secondly, understand the current ecosystem your customer is working within. Is your customer in the news? What’s happening in their industry? What threats and opportunities are arising in their business? Being prepared and knowledgeable about their inner workings will make a better impression than coming in blind.

Decide who you’re meeting with.

Start by setting up a meeting with relevant company leadership. That could be the CEO, the founders, or the VP of the functional team you're working with — depending on the company's scale. Bear in mind, while this contact might be the "reason" for your visit, they're probably not who you'll be spending the most time with.

Once you have a meeting scheduled with the company's leadership, plan the rest of your day around meeting with the team leaders and employees using your product — as well as any teams that are open to signing up or expanding the current seat count or contract scope.

Make dinner reservations for you and your clients.

Traditionally, a customer visit includes taking your client out for a nice dinner as a token of appreciation. It also offers a chance for you to get to know each other outside of the limits of the work environment and form stronger relationships.

That being said, this is not a social visit. Keep your goals in mind — even outside of work hours. If you’re familiar with the restaurants in the area, choose a place that has options for every diet and has a good atmosphere for conversations. If you’re not familiar with the available options, ask the client where they’d recommend.

Complete the wrap-up report.

After the visit is over, you still have work to do. Create a wrap-up report for your internal teams back at the office. It should cover key elements of the visit like any confidentiality agreements put in place and who at your company you can share contact information or sales figures with.

Identify any action items that came up during the visit. Include any positive highlights during the meeting as well as any risks or opportunities that arose. Create a copy of the report for your client as well, to show that you were listening to their concerns and that you’re going to follow up with them.

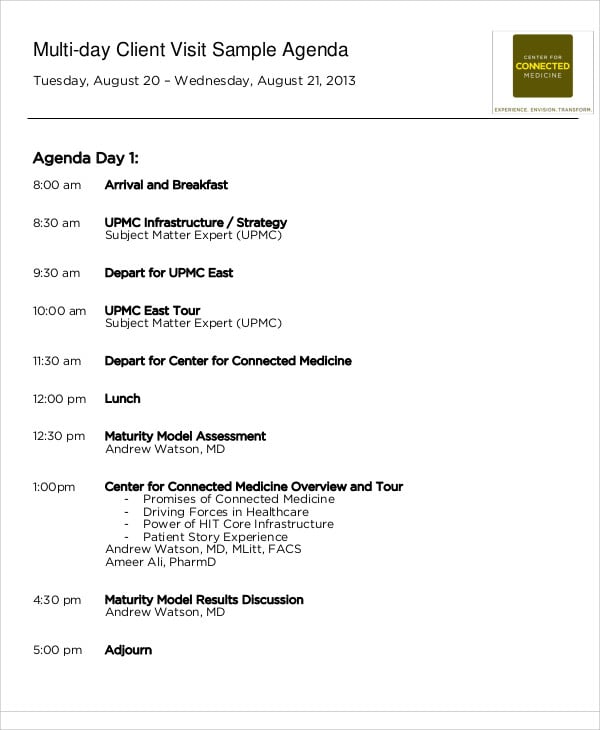

Customer Visit Agenda Template

Use this sample agenda to plan your own customer visit.

10 am: Welcome/Office Tour (30 minutes, w/ Stacy, Raul)

- Get settled, set up a desk or boardroom for the day

11 am: Executive Meeting (1 hour, w/ Stacy, Thomas, Ankit, Shireen)

- Overview of status, product usage, any updates

- Add any bullet points you need to cover here

- Upcoming changes or challenges for the business

- New Opportunities

- Areas of concern

12pm: Lunch

1pm: User Meetings (4 hours, rotating through Marketing teams)

- Overview of new features

- Gather feedback from users

- Sit with teams to review workflow

5pm: Wrap Up meeting (30 minutes)

- Process or configuration change recommendations

- General questions and answers

- Items to be addressed as part of maintenance

- Enhancement opportunities

6:30pm: Dinner at Restaurant

Internal Notes

- At the bottom of your agenda, include internal notes that are meant to be shared with your team only.

Plan for success

It’s time to get back out there and meet your clients face-to-face. By planning your customer visit ahead of time, you’re sure to achieve your goals and come out with a stronger understanding of what your clients need.

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

9 Bad Sales Habits (& How to Break Them In 2024), According to Sales Leaders

![visit agenda meaning 22 Best Sales Strategies, Plans, & Initiatives for Success [Templates]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/Best-Sales-Strategies-1.png)

22 Best Sales Strategies, Plans, & Initiatives for Success [Templates]

9 Key Social Selling Tips, According to Experts

![visit agenda meaning 7 Social Selling Trends to Leverage This Year [New Data]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/social%20selling%20trends.png)

7 Social Selling Trends to Leverage This Year [New Data]

![visit agenda meaning How Do Buyers Prefer to Interact With Sales Reps? [New Data]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/person%20phone%20or%20online%20sales%20FI.png)

How Do Buyers Prefer to Interact With Sales Reps? [New Data]

![visit agenda meaning 7 Sales Tips You Need to Know For 2024 [Expert Insights]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/Sales%20Tips%202024%20FI.png)

7 Sales Tips You Need to Know For 2024 [Expert Insights]

What is Sales Planning? How to Create a Sales Plan

Sales Tech: What Is It + What Does Your Team Really Need?

![visit agenda meaning 10 Key Sales Challenges for 2024 [+How You Can Overcome Them]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/sales%20challenges%20FI.png)

10 Key Sales Challenges for 2024 [+How You Can Overcome Them]

![visit agenda meaning The Top Sales Trends of 2024 & How To Leverage Them [New Data + Expert Tips]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/sales-trends-2023.png)

The Top Sales Trends of 2024 & How To Leverage Them [New Data + Expert Tips]

Free email, survey, and buyer persona templates to help you engage and delight your customers.

Powerful and easy-to-use sales software that drives productivity, enables customer connection, and supports growing sales orgs

Difference between AGENDA, ITINERARY, and SCHEDULE

An agenda is a list or program of things to be done. Workers who are well-organized will often have an agenda for meetings – a list of specific topics to discuss, or things to accomplish during the meeting.

If something is “on the agenda” or “on your agenda,” it means that people are willing to discuss it or work on it.

We also have the expression “a hidden agenda,” meaning a secret plan that you are hiding by pretending you have a different intention.

Some people also use the word agenda to mean their calendar. If someone asks if you are free for lunch next week, you might say, “Let me check my agenda” to find out which day you are available.

The word itinerary is a list or plan of things to do during a trip. On an organized tour, the travel agency will give the travelers an itinerary describing the different places they will go and things they will see.

A schedule is a list of things to be done at a certain time. A conference, for example, might have a schedule like this:

- Breakfast 7-9 AM

- Main speaker 9-10:30 AM

- Workshop 11-12

- Lunch 12-2 PM

Public transportation like buses and trains also have schedules. Another word for schedule, when used as a noun, is “timetable.”

Schedules can also be for long-term projects – the schedule defines what tasks must be done by a certain date. For example, the construction of a building:

- Lay the foundation – by Feb. 1

- Build the structure – by July 1

- Install the electrical systems – by August 1

If something is done or progressing faster than expected, it is “ahead of schedule” – and if something is delayed, it is “behind schedule.”

Finally, the word schedule is used as a verb for establishing an appointment or action at a certain time, for example: “I scheduled my dentist appointment for next Thursday.”

Clear up your doubts about confusing words… and use English more confidently!

More Espresso English Lessons:

About the author.

Shayna Oliveira

Shayna Oliveira is the founder of Espresso English, where you can improve your English fast - even if you don’t have much time to study. Millions of students are learning English from her clear, friendly, and practical lessons! Shayna is a CELTA-certified teacher with 10+ years of experience helping English learners become more fluent in her English courses.

All Formats

Agenda Templates

10+ sample visit agenda.

Visitors don’t come often. They visit for a purpose, and they are only available for a certain period of time. Any event or occasion that ranges from formal to casual ones could definitely involve visitors. They come for different reasons be it academic conferences, workshops, seminars, training sessions, and a lot more.

Agenda Template Bundle

- Google Docs

Business Agenda Template Bundle

Meeting Agenda Template Bundle

Simple Visit Agenda Action Items Template

Free Business Visit Agenda Template

Client Visit Agenda Sample

Free Corporate Visit Agenda

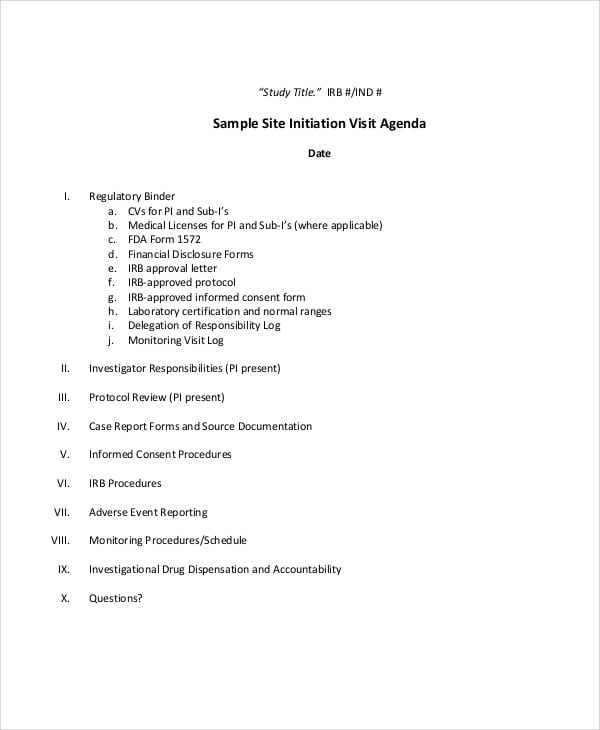

Free Project Site Visit Agenda

Free Industrial Visit Agenda

What is a Visit Agenda?

How to prepare a visit agenda.

- Assign assistants. As a host for a certain conference for example, you have to assign assistants before hand so you could finally prepare a visit agenda. Once they’re assigned on different posts, it would be a lot easier to plot their information in your visit agenda.

- Know visitor’s details first. You are expected to know your visitor’s details before anyone else. An estimated time of arrival is an example of a vital visitor detail. With your initial information obtained, the rest of the details in your visit agenda would all just follow.

Free Site Visit Agenda Template

Company Site Visit Agenda Sample

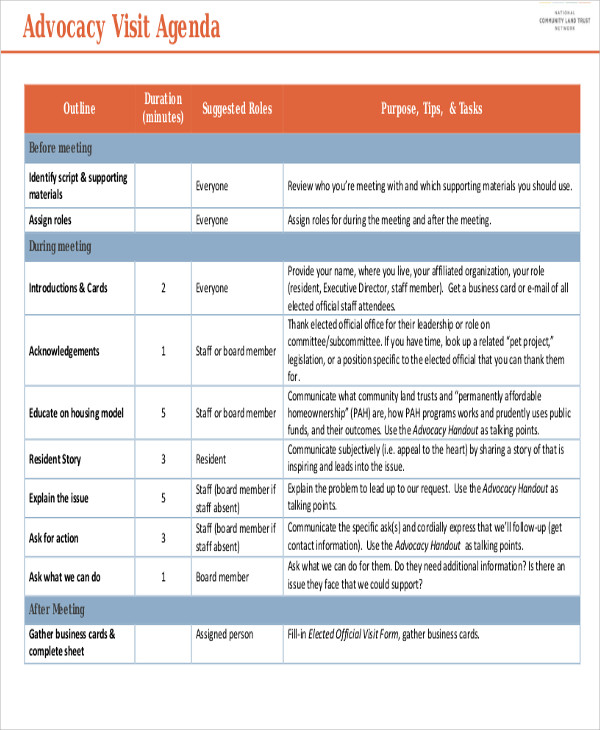

Free Advocacy Visit Agenda in PDF

Sample Visit Agenda

Free Site Initiation Visit Agenda in PDF

Sample Visit Agenda Templates

- This Corporate Visit Agenda Template is presented in a table. It would be much easier for you to plot your visitor’s schedule and corresponding activities as well.

- We also offer a Project Site Visit Agenda Template , which is already written for you in subparts. All you need to do is input the different activities that you have prepared for your visitors. You could also plot any of their preferred schedule. Either way, you already have it all organized.

More in Agenda Templates

Simple industry visit report template, hospital site visit report template, it site visit report template, technical site visit report template, project site visit report template, sales site visit report template, hotel site visit report template, security site visit report template, job site visit report template, customer site visit report template.

- 11+ Training Agenda Templates

- 25+ Simple Agenda Templates – PDF, DOC

- Hourly Schedule Template – 34+ Free Word, Excel, PDF Format Download!

- 10+ Audit Committee Meeting Agenda Templates in PDF | MS Word

- 11+ Retirement Agenda Templates in PDF | DOC

- 12+ Sales Meeting Agenda Templates – Free Sample, Example Format Download

- 10+ Investment Committee Agenda Templates in PDF | DOC

- 10+ Internal Audit Agenda Templates in PDF | DOC

- 10+ Audit Meeting Agenda Templates in DOC | PDF

- 6+ Office Agenda Templates in PDF | Word

- 10+ Retail Meeting Agenda Templates in PDF | Word

- 10+ School Agenda Templates in PDF | DOC | Pages

- 6+ Church Staff Meeting Agenda Templates in PDF

- 10+ Church Meeting Agenda Templates in PDF | DOC

- 10+ Church Nursery Schedule Templates in PDF | DOC

File Formats

Word templates, google docs templates, excel templates, powerpoint templates, google sheets templates, google slides templates, pdf templates, publisher templates, psd templates, indesign templates, illustrator templates, pages templates, keynote templates, numbers templates, outlook templates.

.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:42px;color:#F5F4F3;}@media (max-width: 1120px){.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:12px;}} Discover how today’s most successful IT leaders stand out from the rest. .css-1ixh9fn{display:inline-block;}@media (max-width: 480px){.css-1ixh9fn{display:block;margin-top:12px;}} .css-1uaoevr-heading-6{font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-1uaoevr-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} .css-ora5nu-heading-6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:start;-ms-flex-pack:start;-webkit-justify-content:flex-start;justify-content:flex-start;color:#0D0E10;-webkit-transition:all 0.3s;transition:all 0.3s;position:relative;font-size:16px;line-height:28px;padding:0;font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{border-bottom:0;color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover path{fill:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div{border-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div:before{border-left-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active{border-bottom:0;background-color:#EBE8E8;color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active path{fill:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div{border-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div:before{border-left-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} Read the report .css-1k6cidy{width:11px;height:11px;margin-left:8px;}.css-1k6cidy path{fill:currentColor;}

- Project management |

- Meeting agenda examples: How to plan, w ...

Meeting agenda examples: How to plan, write, and implement

Your agenda tells your team what to expect during a meeting and how they can prepare for it. Ideally, you’ll use your agenda to connect your team with the meeting’s purpose, assign tasks or items to team members, and designate a realistic amount of time to each agenda item. A great meeting agenda maximizes the meeting’s effectiveness and keeps your team on track.

An effective agenda communicates the purpose of your meeting, gives your team the chance to prepare their agenda items, and keeps everyone on track.

Whether you’re preparing for your next board meeting, staff meeting, or business meeting, we’ll help you write an agenda that will maximize your meeting’s potential.

What is a meeting agenda?

A meeting agenda serves as a structured roadmap for your meeting, detailing the topics and activities planned. Its primary role is to provide meeting participants with a clear framework, outlining the sequence of events, the leader for each agenda item, and the time allocated for each task. By having this agenda as a guide both before and throughout the meeting, it helps to facilitate an efficient and productive flow of discussion.

How to write a meeting agenda

Crafting a meeting agenda is a key step in ensuring a focused and productive meeting. Here's how to do it effectively.

1. Clarify meeting objectives

The first step in writing a meeting agenda is to clearly define any goals. In clarifying the goal, be as specific as possible. This specificity helps guide the discussion and ensure that the meeting remains focused. It also helps stakeholders prepare for the meeting.

For example, if the goal is to finalize the budget for the next quarter or discuss new business, participants would come prepared with relevant data and insights.

A well-defined goal also helps set the meeting's tone and align everyone's expectations. This clarity leads to a more structured discussion and a more productive meeting overall.

![visit agenda meaning [inline illustration] how to state the purpose of a meeting in an agenda (infographic)](https://assets.asana.biz/transform/a0ab802a-907c-41cc-b646-0624a08c4f9f/inline-project-management-meeting-agenda-2-2x?io=transform:fill,width:2560&format=webp)

2. Invite participant input

Inviting input from participants before finalizing the agenda is a critical step in creating a comprehensive and inclusive meeting plan. This involves reaching out to potential attendees and asking if there's anything specific they would like to discuss or add to the meeting agenda.

For example, if you're planning a meeting for a project team, you could send an email asking each member to suggest topics they feel are important to address. This could reveal issues or ideas you hadn't considered, ensuring a more well-rounded agenda.

Incorporating participant input not only makes the agenda more comprehensive but also increases engagement. When team members see their suggestions included, they feel valued and are more likely to participate actively in the meeting. It also ensures that the meeting addresses the concerns of all attendees.

Gathering input can be done through various channels, like email, shared docs, or team collaboration tools. The key is to make it easy for meeting participants to contribute and to ensure their suggestions are considered and, where appropriate, included in the final agenda.

3. Outline key questions for discussion

Making a list of important things to talk about is important for keeping the meeting on track and focused. Start by identifying the main meeting topics that need to be addressed and framing them as questions.

For instance, if the meeting is to discuss the progress of an ongoing project, key questions might include:

What are the current roadblocks in the project?

How are we tracking against the project timeline

What resources are needed to maintain the pace of work?

These questions serve as talking points and a guide for the discussion, ensuring that all relevant topics are covered. They also help in structuring the conversation, making it easier for participants to prepare and engage effectively.

4. Define each task’s purpose

Each task or topic on the agenda should have a clearly defined purpose. This transparency helps participants understand the importance of each discussion point and how it relates to the overall goal of the meeting.

For example, if one of the agenda items is to review recent client feedback and performance metrics, the purpose might be to identify areas for improvement in customer service. By stating this purpose, participants can focus their thoughts on this specific objective, leading to a more targeted and fruitful discussion.

Defining the purpose of each task also helps prevent the meeting from going off track. When participants understand why a topic is being discussed, they are less likely to veer off-topic, making the meeting more efficient.

5. Allocate time for agenda items

Effective meeting management requires allotting time for each item on the agenda. This includes determining the amount of time needed for each meeting topic or task and scheduling the meeting appropriately.

For instance, if you have five items on your agenda, you might allocate 10 minutes for a brief update, 20 minutes for brainstorming, and 15 minutes for discussing action items. This time allocation should be based on the complexity and importance of each topic.

Effective time management requires being realistic with your time estimates and factoring in extra time for unforeseen conversations or inquiries. This approach helps in keeping the meeting within the scheduled time frame, respecting everyone's time, and maintaining focus.

6. Assign topic facilitators

Assigning facilitators for each topic on the agenda can greatly enhance the effectiveness of the meeting. A facilitator’s role is to guide the discussion, make certain that the conversation stays on track, and that all voices are heard.

For example, if one of the agenda items is to discuss sales strategies, you might assign this topic to a senior salesperson. Their expertise and familiarity with the subject can help steer the conversation productively.

Facilitators should be chosen based on their knowledge of the topic and their ability to manage group discussions. They should also be briefed on their role and the expectations for the discussion.

7. Write the meeting agenda

Finally, compile all the elements into a structured and comprehensive agenda. The agenda should include the meeting’s goal, a list of topics to be discussed with their purposes, time allocations, and assigned facilitators. This structure provides a clear roadmap for the meeting, ensuring that all important points are covered.

Share the agenda with all participants well in advance of the meeting. This allows them to prepare and ensures that everyone is on the same page. A well-written agenda is a key tool in running an effective and productive meeting.

Tips to create an effective meeting agenda

Let’s start with some of our favorite tips on creating great meeting agendas so you can make the most of yours:

Create and share your meeting agenda as early as possible. At the very latest, you should share your meeting agenda an hour before the meeting time. This allows everyone to prepare for what’s going to happen. Your team can also relay questions or additional agenda items to you for a potential adjustment before the meeting. Besides, when your team members have a chance to properly prepare themselves, they’ll have a much easier time focusing during the meeting.

Link to any relevant pre-reading materials in advance. This can be the presentation deck, additional context, or a previous decision. Everyone arriving at the meeting will be on the same page and ready to move the discussion forward rather than asking a ton of questions that take up relevant time.

Assign facilitators for each agenda item. Remember that feeling of being called on in school when you didn’t know the answer? It’s a pretty terrible feeling that we’re sure you don’t want to evoke in your teammates. By assigning a facilitator for each agenda item before the meeting, you allow them to prepare for a quick rundown of the topic, questions, and feedback.

Define and prioritize your agenda items. Differentiate between the three categories of agenda items: informational, discussion topics, and action items. Clarifying the purpose of each agenda item helps your team member understand what’s most important and what to focus on. You’ll also want to prioritize which items are most important and absolutely have to be discussed during the meeting and which ones can be addressed asynchronously, should the clock run out.

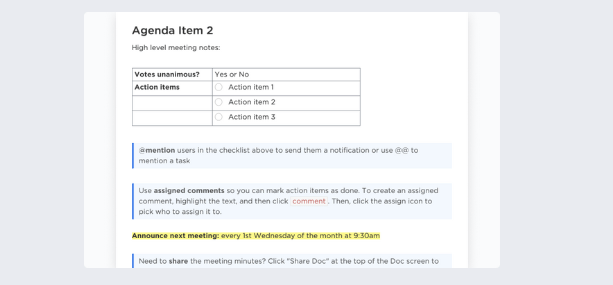

Use your meeting agenda during the meeting to track notes and action items. That way, all of the meeting information is in one place. If anyone has questions about decisions or action items from the meeting, they have an easy place to find it. Bonus: Do this in Asana so you can assign out action items and next steps to ensure nothing falls through the cracks. Asana also integrates with Zoom and pulls in your Zoom recording or meeting transcript directly into the meeting agenda task.

![visit agenda meaning [inline illustration] 3 types of agenda items (infographic)](https://assets.asana.biz/transform/e2155679-568e-435d-87c9-7bcfd909f0b9/inline-project-management-meeting-agenda-3-2x?io=transform:fill,width:2560&format=webp)

Create flow by categorizing your agenda items. To maximize productivity, you’ll want to create a meeting agenda that flows well. Batch similar items together and ensure they can build off of one another. For example, list any informational items before the discussion items so your team has all of the information going into the discussion.

Allocate enough time for each item on your agenda. Nobody will complain about a meeting that runs short—keeping everyone longer than anticipated isn’t as much fun. Plan sufficient time for each agenda item by calculating an estimated time and adding a couple of minutes as a buffer. This will help with keeping your team on track and moving on from a topic when the time runs out.

By sticking to these best practices, you can ensure that your meeting agenda is a reliable tool and does the job—before, during, and after your meeting.

Why are meeting agendas important?

Whether you work from home and take virtual calls or sit in the office and meet in person, meetings can be incredibly draining. Beginning with some small talk may be nice to get to know each other better or catch up on what everyone did this past weekend but it certainly isn’t goal-oriented or productive. A meeting agenda can help your team maximize the potential of each meeting you hold.

Our research shows that unnecessary meetings accounted for 157 hours of “work” in 2020, compared to 103 in 2019. Considering a 40-hour work week, that’s almost four weeks of wasted time. This is where your meeting agenda comes in. If you’re doing it right, writing your meeting agenda is the first and best indicator of whether or not your meeting is actually necessary. If you find that everything on your meeting agenda can be discussed asynchronously , you can cancel the meeting and share your message in a time-saving email.

That isn’t to say all meetings should be replaced by emails. If you’re sure that the meeting is justified and necessary in order to drive your team’s progress, have that meeting. However, always make sure that you create an agenda before getting together so your team members know what you’ll be discussing and why the meeting matters.

Here are a few more great reasons to have meeting agendas:

Your agenda allows everyone to prepare for the meeting. Ideally, every item on your agenda will have a dedicated topic facilitator. When everyone going into the meeting knows what their responsibilities are in advance, they have time to prepare and will be more efficient during the meeting.

It shows you’re considerate of your team’s time. When your team receives a well-thought-out meeting agenda, they’ll immediately see that the meeting is actually necessary. Besides, it’s also a roadmap that will keep you on track during the meeting and ensure no time is wasted.

![visit agenda meaning [inline illustration] be considerate of your team's time in a meeting (infographic)](https://assets.asana.biz/transform/002c4cb6-0ec6-422a-9279-8a57ab5b75f4/inline-project-management-meeting-agenda-1-2x?io=transform:fill,width:2560&format=webp)

An agenda sets clear expectations of what will and won’t be discussed. Think of a meeting agenda as a way of setting boundaries and ensuring that only topics on the agenda will be talked about. If anything comes up during the meeting that needs to be discussed, write it down in your minutes and return to it later. Either at the end of your meeting—if you got through it faster than expected—asynchronously, or in the next meeting.

It keeps your team on track. Your meeting agenda will prevent your team from drifting off—whether that’s discussing non-agenda topics (like the barbecue at Kat’s place last night) or taking too much time for an item that had specific time allocated.

Your agenda will provide purpose, structure, and opportunities to collaborate. With a clear plan for everyone to follow, your team will go into the meeting knowing the purpose and goal of the meeting. Your meeting agenda also allows your team to direct their attention toward opportunities to collaborate, whether that’s during a brainstorming session , a town hall, or your daily standup.

Track next steps and action items so nothing falls through the cracks. Keep your agenda open during the meeting to capture any next steps or action items . By adding them directly into the agenda, these items won’t be forgotten when the meeting ends.

Meetings are great opportunities for your team to bond but the time spent on small talk can be worked into the first few minutes of the agenda rather than surfacing every now and then during the meeting, disrupting the flow and productivity or your team’s discussion.

Meeting agenda examples

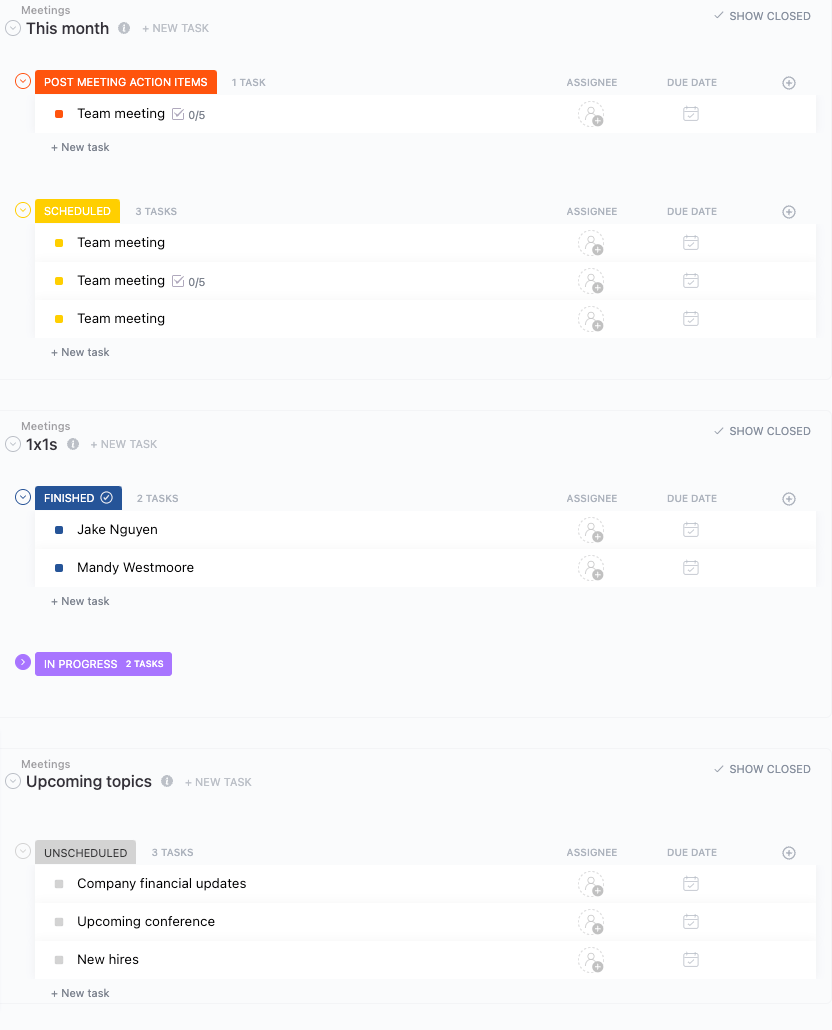

We’ve discussed what makes a good meeting agenda and what you should avoid doing but, as always, it’s easiest to learn from a real life example. Let’s take a look at a project kickoff meeting agenda created in Asana:

![visit agenda meaning [Product UI] Meeting agenda, project kickoff in Asana (Tasks)](https://assets.asana.biz/transform/4108d52d-ac5c-47cf-9af8-5e6c7568b881/Project-kickoff-meeting-agenda_1400?io=transform:fill,width:2560&format=webp)

As you can see, each item has a timebox and a teammate assigned to ensure everyone knows when it’s their turn and how long they have to lead their discussion or give their presentation. The agenda also has relevant files attached and is shared with all team members for visibility and better collaboration.

Meetings are a staple in the professional world, each with its own unique focus and dynamics. Understanding how to tailor your meeting agenda to the type of meeting you're conducting is key to ensuring effective communication and teamwork. Here are some common types of meetings and examples of how to structure their agendas.

Team meeting agenda

Team meetings serve as a platform for team building, decision making, and brainstorming. They can vary in frequency and duration but are essential for ensuring alignment and forward momentum. Effective team meeting agendas should include recurring items for regular meetings and space for new, ad-hoc topics. It’s also vital to track next steps and responsibilities assigned during the meeting. An example of a 45-minute team meeting agenda might cover metrics, a round-table plan, identification of blockers, and recognition of team members' contributions.

Daily Scrum meeting agenda

Daily scrum meetings, or stand-ups , are brief, focused gatherings aimed at keeping the team aligned during a sprint. These meetings typically cover blockers, a recap of the previous day’s work, goals for the current day, and progress towards sprint goals. The agility of these meetings helps in maintaining momentum and addressing issues promptly.

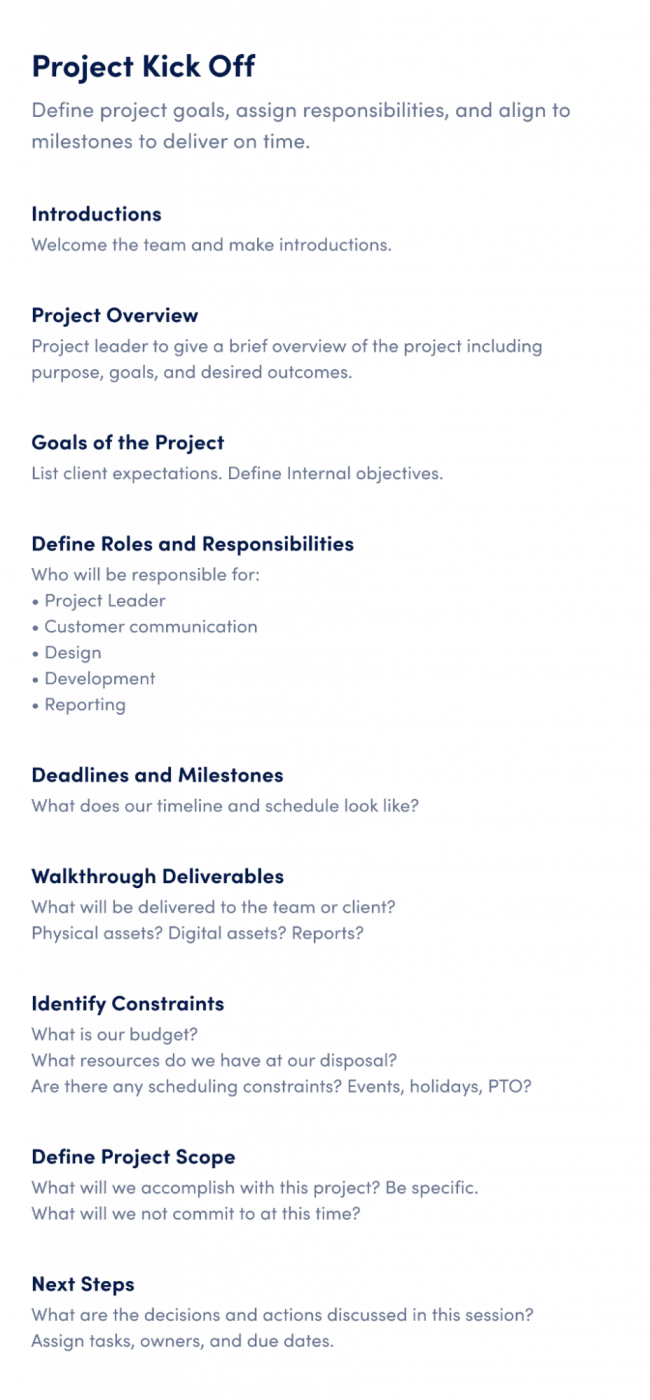

Project kickoff meeting agenda

Project kickoff meetings bring together cross-functional teams to start a new project. These meetings set the tone for the project and align everyone on objectives and expectations. The agenda should cover the project brief, roles and responsibilities, meeting cadence, actionable next steps, and a Q&A session to clarify doubts and ensure everyone is on the same page.

Retrospective meeting agenda

A retrospective meeting is a type of recurring meeting focused on reflecting on a past period of work, usually at the end of a project cycle or sprint. Its main purpose is to share information among team members about what worked well and what didn't. During the meeting, the entire team discusses various meeting topics, including successes, challenges, and blockers that impacted their work. This process helps in identifying areas for improvement and developing strategies to address any issues. Retrospective meetings are vital for continuous team development and ensuring better outcomes in future work cycles.

One-on-one meeting agenda

One-on-one meetings , whether they are between a manager and a direct report, peer-to-peer, or skip-level, are crucial for discussing work projects, roadblocks, and career development. They are foundational for building trust.

A good agenda for these meetings should balance topics like motivation, communication, growth, and work-related discussions. Avoid status updates; those are better suited for stand-up meetings. Sample questions for a weekly one-on-one might include assessing highlights and lowlights of the week, discussing any blockers, and inquiring about work-life balance.

Remote one-on-one meeting agenda

Remote one-on-one meetings require a slightly different approach, with a focus on rapport-building and clear communication. Since physical presence is lacking, these meetings benefit from a shared online agenda accessible to all participants. Key points could include checking in on general well-being, discussing current work assignments, and addressing any immediate concerns or assistance needed.

Skip-level meeting agenda

Skip-level meetings, involving senior managers and employees not in their direct report chain, offer a chance to connect across organizational levels. These meetings are ideal for discussing broader career development and providing feedback to senior leadership. Agenda items might cover clarity on company strategies and goals, personal professional objectives, and suggestions for organizational improvements.

Leadership team meeting agenda

Leadership team meetings are vital for strategic decision-making and issue resolution at the highest levels of an organization. An effective agenda for such meetings might include personal updates, reviewing key metrics, sharing wins and insights, discussing important messages, addressing pressing issues, and allocating time for an open discussion or "hot seat" session where specific topics are addressed in-depth.

Each type of meeting, be it an all-hands gathering, one-on-one discussion, performance review, or team brainstorming session, requires a thoughtfully crafted agenda to avoid unproductive meetings and keep discussions on track.

By using these meeting agenda examples, you can ensure that each meeting, regardless of its format, contributes meaningfully to the organization's goals and enhances teamwork and collaboration.

Running an effective meeting

It’s one thing to have an amazingly organized and detailed agenda that your team can reference before the meeting—using it as a tool during the meeting is a whole other ballpark. These tips will help you make your meeting agenda as useful during the meeting as it is as a preparation tool

Stick to your agenda. The best agenda becomes useless if you don’t stick to it during the meeting. Try not to bounce back and forth between agenda items but rather stick to the priorities you established earlier.

Stick to your timeboxes. It absolutely helps release some tension and lighten the mood if you have a bit of small talk or a quick check-in at the beginning of your meeting. That’s why you should allocate three to five minutes to this—and stick to the timeframe. Pictures of Kabir’s son’s adorable Halloween costume can be shared elsewhere so you have enough time to reach your meeting’s goals now.

Designate a note taker. At the beginning of the meeting, designate a note taker who will write down any questions, feedback, tasks, and ideas that come up during the meeting. You can rotate this position so everyone on your team gets to contribute at some point. Ideally, these notes are taken in the same place as the meeting agenda—this will make it a lot easier for team members to follow the notes and link them to agenda items. Notes can also be directly entered into Asana for real-time updating and tracking

Follow up after the meeting. Typically, the note taker will be responsible for following up with the meeting notes afterward. The notes should include any decisions that were made during the meeting, tasks that need to be completed, and questions that remained unanswered. If possible, assign teammates and add due dates to action items to keep accountability high. To ensure that these action items are tracked and completed, they should be promptly added to our Asana project management tool.

Make the most out of every meeting

With Asana, you can keep your meeting agenda, meeting minutes, and meeting action items in one place. Effortlessly share the agenda with your team and assign agenda items in real time so nothing falls through the cracks.

Streamlining your meetings with one central tool will reduce the amount of work about work your team faces, connect everyone to the purpose of the meeting, and allow for productive meetings everyone enjoys.

Related resources

How Asana uses work management to optimize resource planning

Understanding dependencies in project management

Program manager vs. project manager: Key differences to know

Critical path method: How to use CPM for project management

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of agenda

Examples of agenda in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'agenda.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

from plural of agendum or its Latin source, taken as a singular noun

1751, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Phrases Containing agenda

- hidden agenda

Articles Related to agenda

All About Latin Plurals

Latin has a few plural forms, so check our dictionary.

Dictionary Entries Near agenda

Cite this entry.

“Agenda.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/agenda. Accessed 21 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of agenda, more from merriam-webster on agenda.

Nglish: Translation of agenda for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of agenda for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day, noblesse oblige.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 19, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), a great big list of bread words, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), games & quizzes.

Filter by Keywords

Project Management

16 meeting agenda examples & free templates.

Evan Gerdisch

Content Strategist

March 25, 2024

We’ve all been a part of team meetings where most participants are clueless about the purpose of the meeting, and the speakers steer the discussion off-track.

What follows is a true catastrophe.

You’d find your team clocking in many unproductive hours because of the ‘said meeting’ without achieving any objective.

Good news!

A meeting agenda can help you avoid this and be the answer to all your woes. ✌

An effective meeting agenda is a plan you share with your meeting participants. It’ll help your team set clear expectations of what needs to happen before, during, and after the meeting.

In this article, we’ll discuss what a meeting agenda is and learn the five key steps involved in writing one. We’ll also look at 16 meeting agenda template options and explore the reasons why your entire team needs a meeting agenda.

Benefits of an Effective Meeting Agenda

How to write a meeting agenda 5 key steps, how to use ai for meeting agendas, team meeting agenda examples, 1. weekly 1-on-1 meeting agenda template by clickup, 2. all hands team meeting agenda template by clickup, 3. scrum meeting agenda template by clickup, 4. meeting notes agenda template by clickup, 5. project post mortem template by clickup, 6. meeting minutes template by clickup, 7. sprint retrospective brainstorm meeting template by clickup, 8. team meeting agenda template by meeting booster, 9. board meeting agenda template by template lab, 10. project kickoff meeting agenda template by docket, 11. meeting dashboard template by clickup, 12. brainstorm meeting agenda template by owl labs, 13. board of directors meeting minutes template by clickup, 14. hr meeting agenda template by where, 15. marketing meeting agenda template by hugo, 16. project management meeting agenda template by hypercontext, who benefits from using a meeting agenda, cross-off stress from your work life with team meeting agendas.

If you’re more of a visual learner check out this vlog on meeting agendas!

Let’s get started.

Sitting through a meeting that doesn’t have an agenda is pretty similar to setting out on a treasure hunt without a map.

A meeting agenda allows your team to set the meeting’s cadence , prepare for the meeting topic, ensure that everyone is on the same page, and keep them on track to hit their objectives.

Meeting agendas:

- Give the meeting a clear purpose

- Help you stay on track

- Help define responsibilities

It consists of a list of topics, action items , and activities you want to discuss during the meeting.

A simple meeting agenda could be a short bulleted list. More detailed agendas include descriptions for each agenda item, reference material, and expected outcomes for each discussion topic.

Formal agendas also include timing and presenter information for each agenda item.

An example of a formal agenda can be a city council agenda used in a state’s city council meeting. These agendas can have an open forum section that makes time for public comment.

But formal meeting agendas aren’t restricted to the government.

You can use them in your company’s meetings too. You just have to choose the agenda that suits your team the best .

Now that you know what a meeting agenda is, let’s look at how you can write one. ✍

Here are the five easy steps you can follow to create the right meeting agenda for your team:

1. Establish the meeting type

Not informing your team about the type of meeting they’d be attending can cause a lot of confusion.

Imagine a team member attending a regular meeting only to find out that it’s their performance review .

The horror! 😱

To avoid catching people off-guard, make sure you all know what the meeting is about.

Meetings can be of several different types, including:

- Team meeting: also referred to as a staff meeting, these are opportunities for your team to discuss various business aspects

- Board meeting: a formal meeting among your organization’s board of directors. They’re generally held at regular intervals to review team performances and policy issues

- Executive session: held by board members regularly before their routine board meetings

- Recurring meeting: daily, weekly, or monthly meetings that repeat regularly

- Project kickoff meeting : conducted at the beginning of every new project to inform the team about project objectives, deliverables, and timelines

- Brainstorming meeting: used to flesh out a new idea with your teams in a conducive brainstorming session

- Feedback meeting: hosted to gather constructive feedback from your team regarding new projects and processes

- Agile meeting : a special meeting used to hold hyper-focused discussions for agile teams to conduct sprint reviews, share valuable project information, customer feedback, project updates, etc.

- Scrum meeting: uses a scrum meeting agenda that may include sprint planning, daily standups, product backlog refinement, sprint reviews, etc.

- Retrospective meeting: held after project completion to discuss what went well and what didn’t

- Onboarding meeting : help new hires understand professional expectations in their work environment

- Committee meetings: help a subgroup of team members from your company form a committee to achieve any special function.

2. State the objective of the meeting

What are the top reasons you’re having a meeting with your team?

Do you want to update them about a project? Do you want their insights on something?

Clearly stating the meeting objective gives your team a heads-up on what’s coming their way. At the very least, they’ll know whether to bring a project report or a beer to the meeting.

3. Identify specific meeting topics

Once you have a clear meeting goal, make a list of discussion topics you want your team to cover.

We’re going to let you in on our secret to make your meetings more engaging.

Make sure to pick discussion topics that affect everyone in the meeting.

This way, you’ll have all your team members willing to participate in the discourse.

Related: Our remote guide to Virtual Meeting Etiquette !

4. Allocate time to discuss each topic

Meetings are expensive and can be difficult to organize. They’re only productive when they can utilize time effectively.

That’s why it’s important to allocate a certain amount of time to discuss each meeting topic. And you won’t end up straying and spending all your available time on a single topic.

Using a consent agenda is another time-saving trick for your meetings. A consent agenda groups recurring discussion topics into a single agenda item that you can easily cross-off.

These measures will make sure your meetings don’t become a time-suck and a calendar clogger. 👀

5. Include a list of necessary documents

Let’s say you hold a meeting with your project stakeholders .

One way to make the meeting more productive is to share all project documents through your team meeting agendas ahead of the meeting.

Think of this as one of the pre-reading activities your teacher would ask you to do back in school. 🤓 This practice sets the right context for every participant in the meeting and empowers them to contribute to the discourse.

Now that you know what to do, let’s look at some meeting agenda examples to help you see what these steps look like in action.

Bonus: Conference agenda templates !

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can significantly streamline meeting management, turning every gathering into an efficient and productive experience. By integrating AI with project management tools like ClickUp Brain , teams can leverage automation to handle routine tasks and enhance meeting productivity. Here’s how AI can assist:

- AI-powered Meeting Agendas : ClickUp’s AI capabilities can draft personalized meeting agendas based on the participants’ roles, previous meeting notes, and ongoing project demands. By analyzing prior meeting notes and objectives, AI can help ensure that each meeting covers all critical points without missing a beat.

- Smart Summarization : Post-meeting, AI can condense hours of discussion notes into succinct, actionable summaries. This feature enables participants to swiftly get the gist of the meeting and review any points they may have missed, ensuring everyone is aligned and informed.

- Instant Action Items Creation : ClickUp AI can identify potential tasks from your notes and automatically create action items in ClickUp. This seamless transition from discussion to execution means that follow-ups are clear, time-bound, and less likely to be overlooked or forgotten.

Embedding AI in your meeting processes not only saves time but also enhances the quality of your meetings. It helps to maintain focus, track progress against objectives, and foster a culture of accountability by automating routine yet crucial aspects of meeting management.

Here’s a couple simple meeting agenda example for your reference:

Design Team Meeting

Date: 02/07/24

Time: 09:00 am – 09:45 am

Meeting Participants: @SpongeBob, @Patrick, @Mr.Krabs, @Squidward

Meeting’s Purpose:

- Develop a new website page for product testimonials

a. Before the meeting:

- Every attendee must review the document on product testimonials

b. Discussion topics:

- Review product testimonials document (10 min)

- Discuss the content you want to include on the web page (10 min, @Name)

- Present sample designs for the web page (15 min, @Name)

- Share suggestions and vote on the website design (10 min)

c. Action items:

- Create a timeline for design deliverables – @SpongeBob

- Share first cut of the web page design – @Patrick

- Schedule and make an itinerary for a second meeting to finalize design – @Mr.Krabs

Sales Team Weekly Review Meeting

Date: 04/14/24

Time: 02:00 pm – 02:45 pm

Meeting Participants: @Alice, @Bob, @Charlie, @Dana

- Evaluate weekly sales performance and discuss strategies for improvement

- Each participant should update the CRM with the latest sales data

- Review weekly sales figures and trends (15 min)

- Discuss obstacles in the sales pipeline and solutions (10 min, @Alice)

- Brainstorm strategies for upcoming sales campaign (10 min, @Bob)

- Set goals for the next week (10 min)

- Compile a report of weekly sales metrics – @Charlie

- Draft a preliminary plan for the sales campaign – @Dana

- Organize a training session on new sales software – @Alice

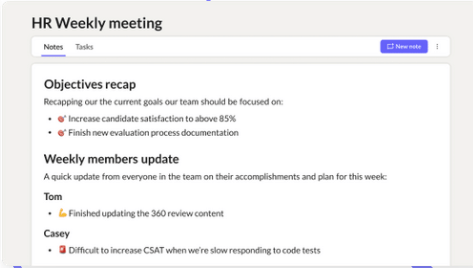

HR Monthly Planning Meeting

Date: 04/21/24

Time: 11:00 am – 12:00 pm

Meeting Participants: @Emma, @Liam, @Noah, @Olivia

- Plan HR activities for the next month and update on current employee initiatives

- Review employee feedback from the previous month

- Analyze employee satisfaction survey results (20 min)

- Update on the status of current recruiting efforts (15 min, @Emma)

- Plan employee engagement activities for the next month (15 min, @Noah)

- Discuss updates to HR policies (10 min)

- Implement changes based on employee feedback – @Liam

- Finalize recruitment schedule and process – @Olivia

- Prepare the schedule for upcoming engagement activities – @Emma

These samples should give you an idea of how you want to design your meeting agenda. To help you further, let’s look at some meeting agenda templates from the most popular online meeting tools .

16 Team Meeting Agenda Templates

Here are 16 meeting agenda templates that you can use to create your next agenda:

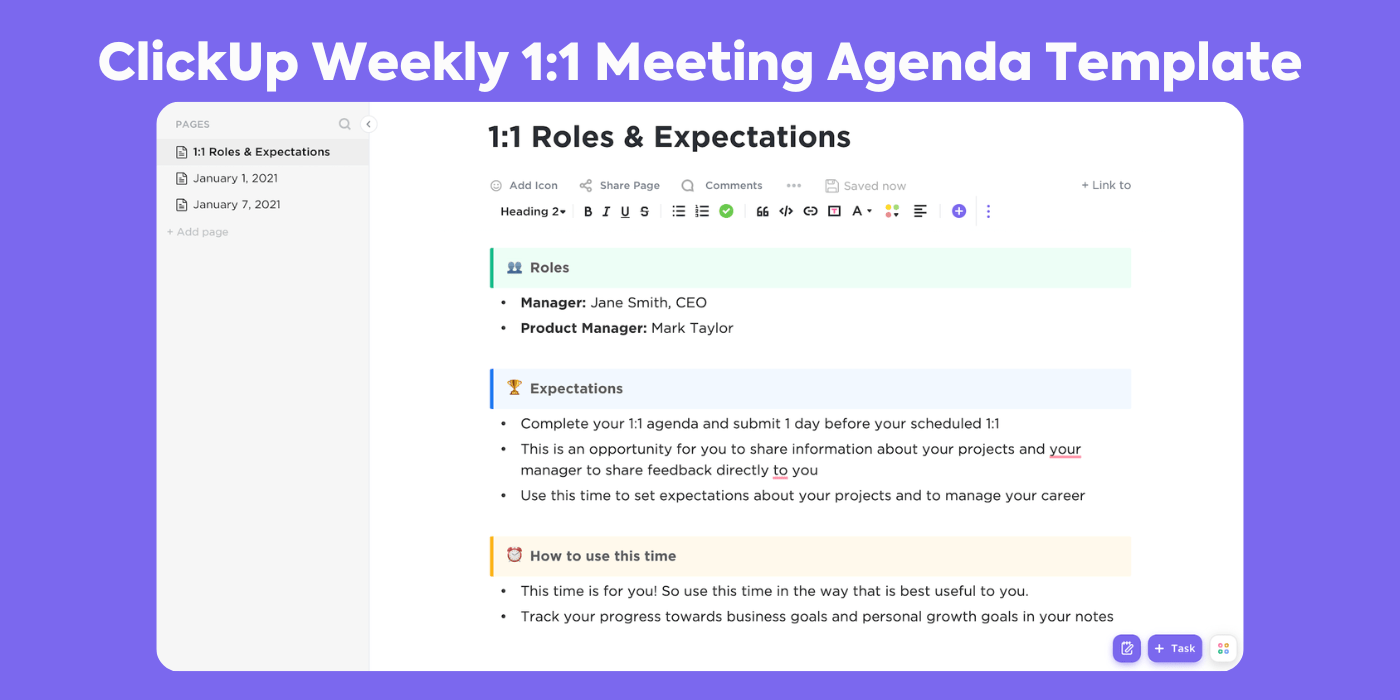

One-on-one meetings are your chance to connect and align with the people you manage in the most effective way possible. ClickUp’s 1:1 meeting template keeps all of your agendas—tailored for each individual—in one organized place.

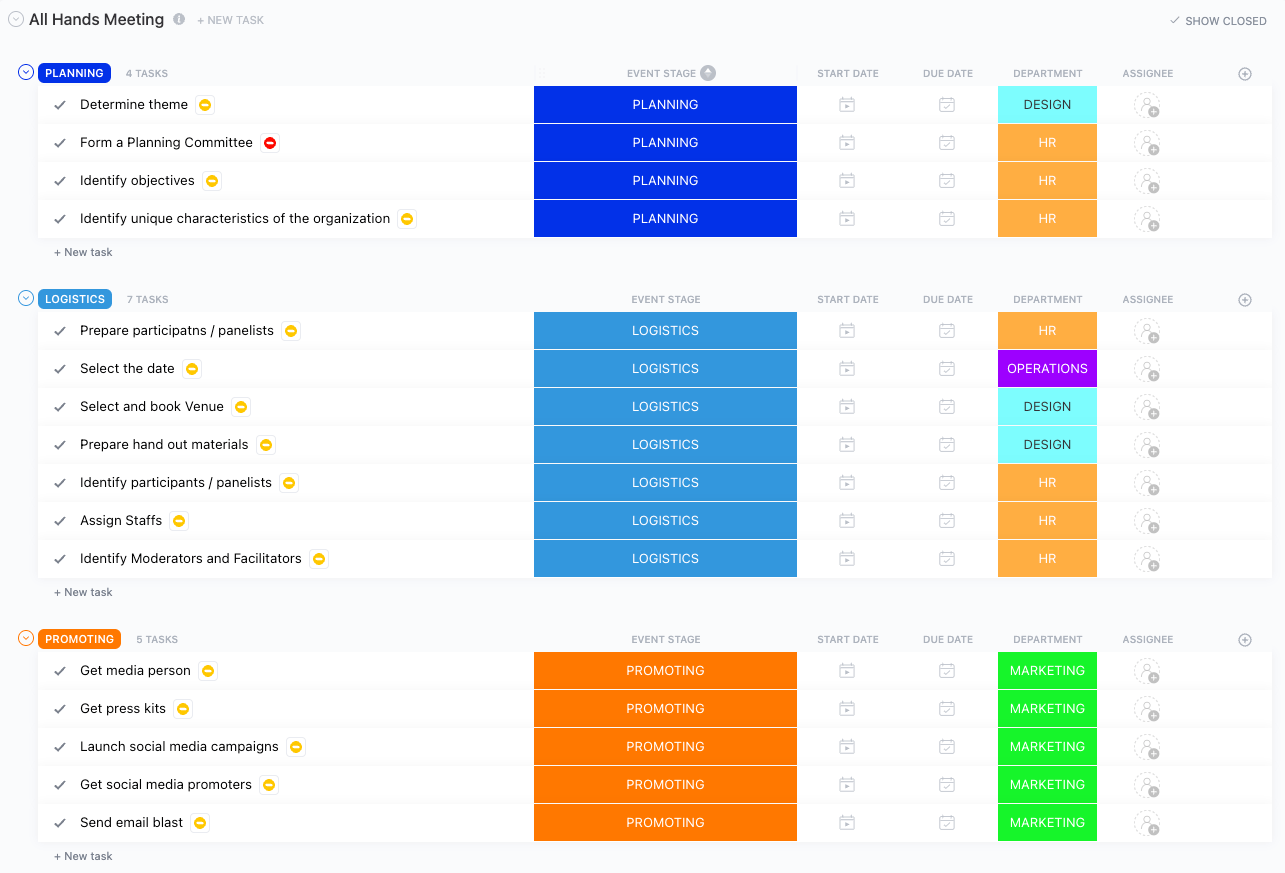

ClickUp’s all-hands meeting template helps to keep communication open across the company, and ensures everyone is aligned and up to speed with individual and group goals. All hands meetings give room to share information from updates to announcements about future agendas and encourage collaboration and alignment throughout the team.

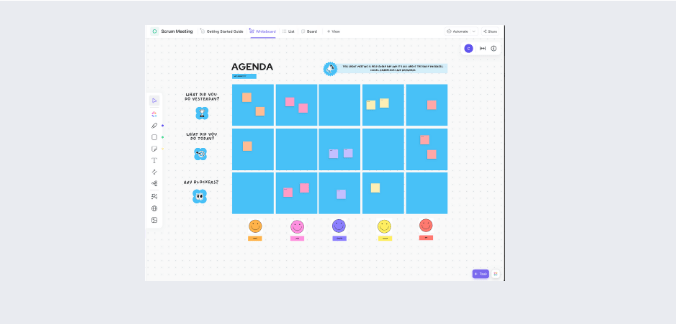

This scrum meeting agenda template by ClickUp will make daily meetings a breeze. Daily status meetings about tasks for projects help to ensure that a team is aware of the progress on their front.

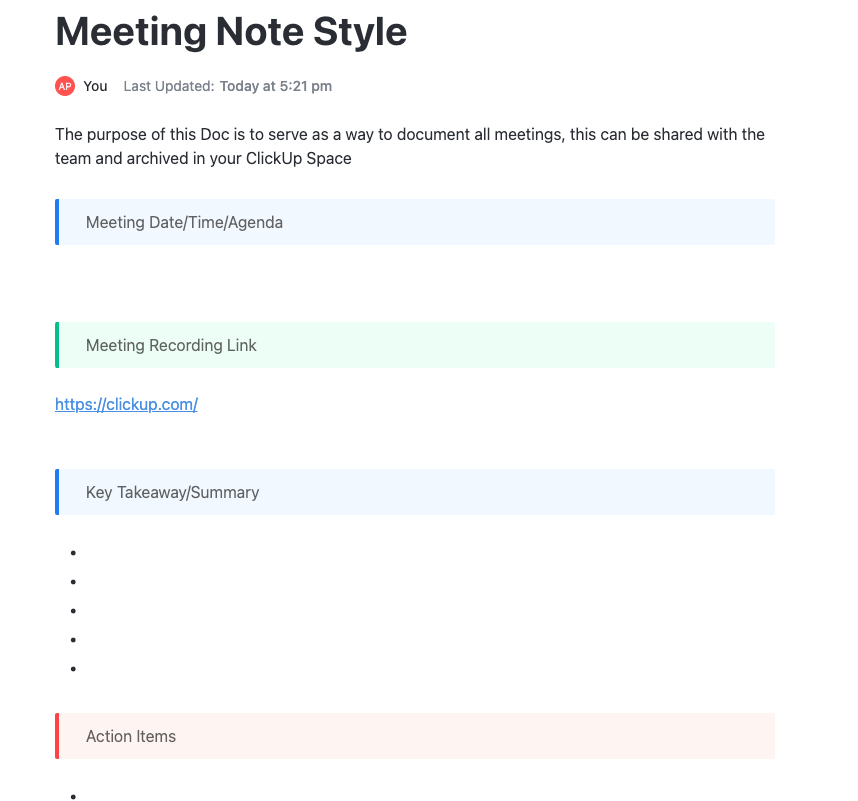

ClickUp’s meeting note-style agenda template is the perfect place to keep all event meeting notes, key takeaways and action items.

Projects don’t always go to plan. Use this project post-mortem template by ClickUp to set new goals and keep your team heading in the right direction.

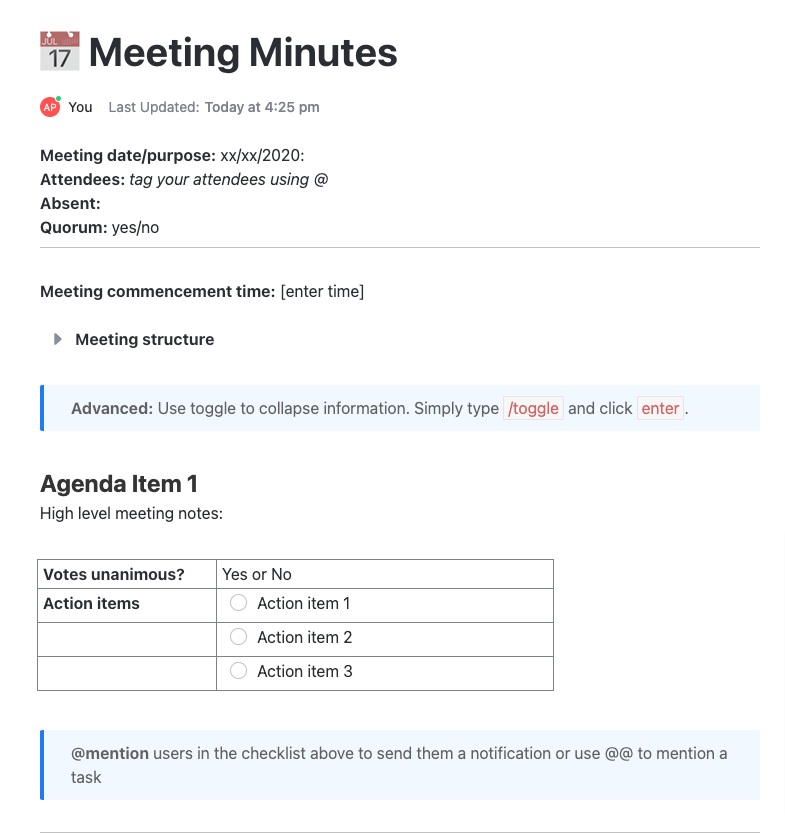

This collaborative meeting minutes template is a ClickUp Doc designed to provide the perfect outline for a successful meeting summation.

ClickUp’s Meeting Minutes Template includes pre-built pages for organizing teams, individual meeting notes , and instructions for getting the most out of your meeting with this template!

Turn your meeting notes into a newsletter with newsletter templates !

Save time and gain valuable insights with this simple Sprint Retrospective Template . Whether you are running an agile team meeting or a project management meeting, this template will help you build a crystal-clear picture of what went well, what didn’t go so well, and what to change moving forward.

The main objective of team meetings is to share important information with team members, align on goals, and call out any blockers. This team meeting agenda template helps the team stay focused on the goals of the meeting.

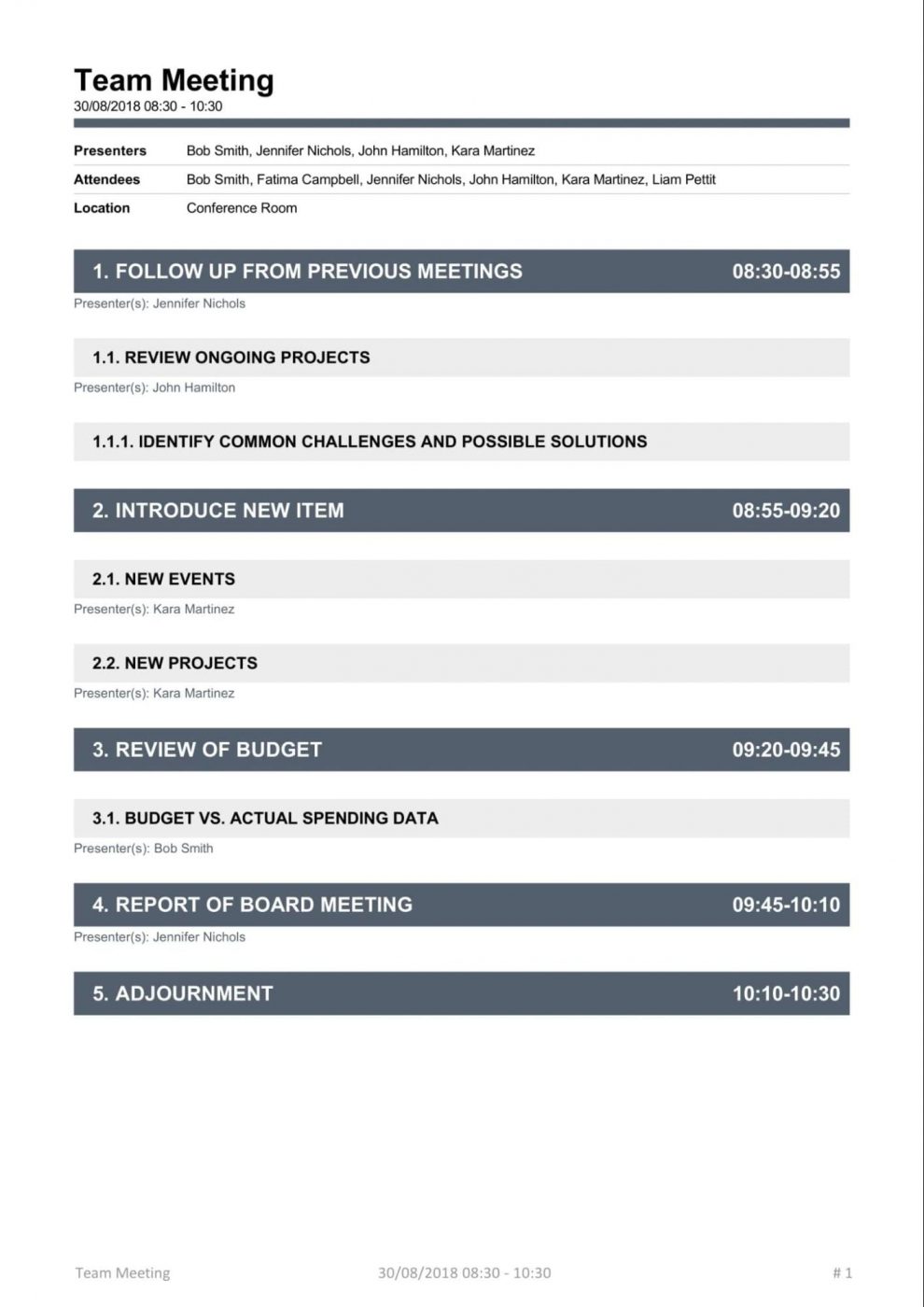

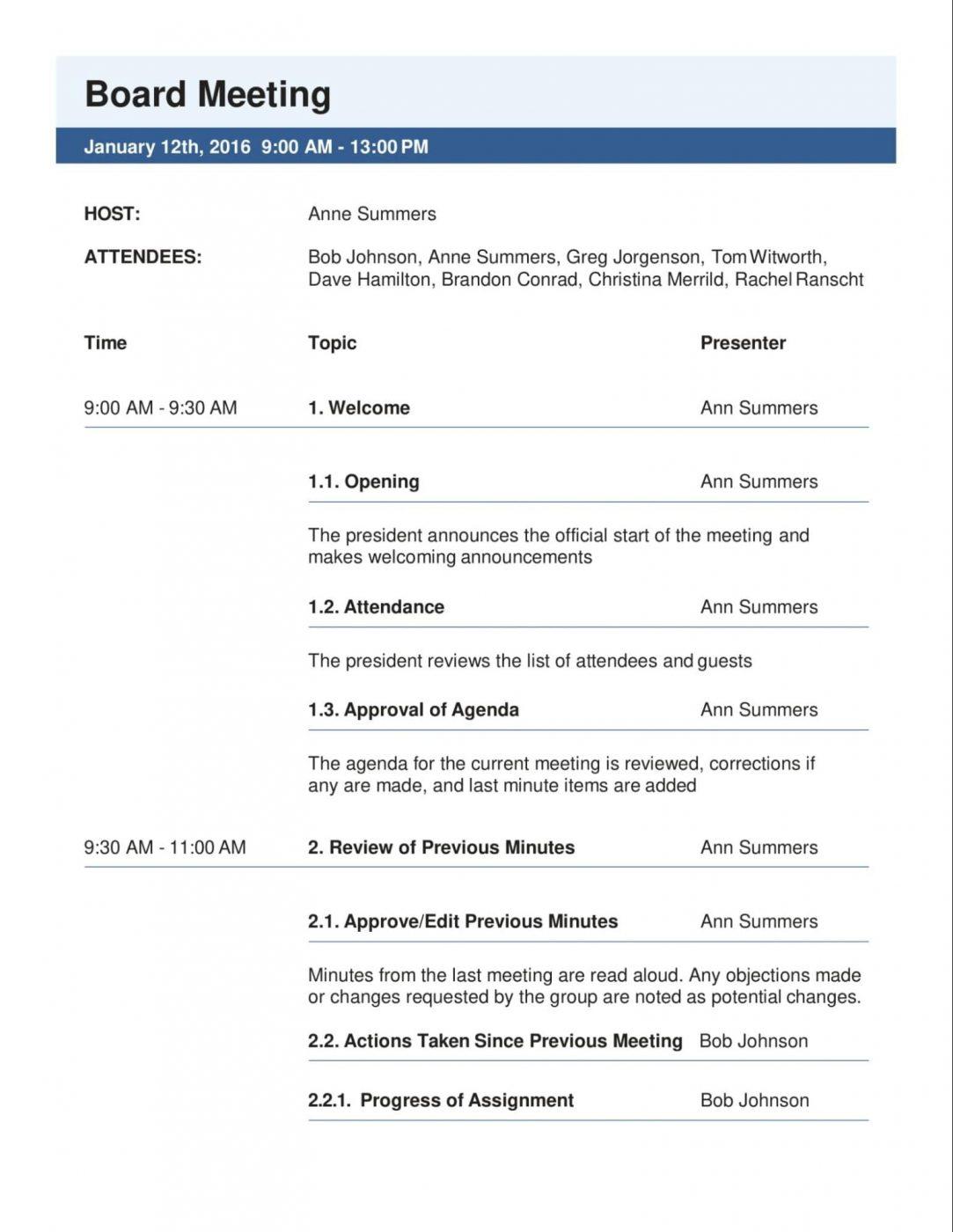

Board meetings tend to run over time. Use a schedule template for your next board meeting using this board meeting agenda to stay on track and finish your meeting on time.

It’s important to set the tone for a new project from the start. Use this project kickoff meeting agenda template to facilitate a successful project launch!

Use this ClickUp meeting dashboard template as an agenda for your next meeting. This template makes it easy to see the status of different tasks during a meeting.

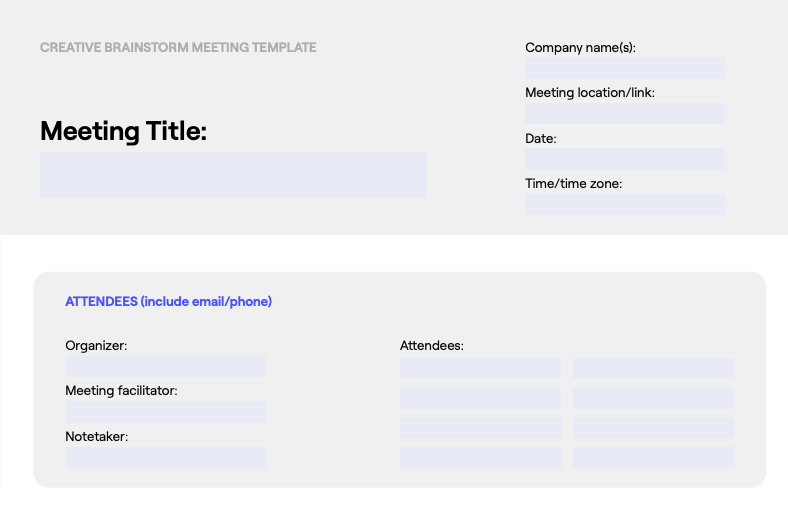

This creative brainstorming meeting agenda is a great way to keep your brainstorming meetings on track from week to week. This template makes it easy to run your meeting and stay focused on brainstorming.

Create structure with this ClickUp Board of Directors Meeting Minutes Template . Record and tag your attendees, organize agenda action items, and take detailed notes for each agenda.

HR departments have a lot to keep track of. This HR meeting agenda template will give your HR team a way to come together for a productive meeting that isn’t complicated or stressful.

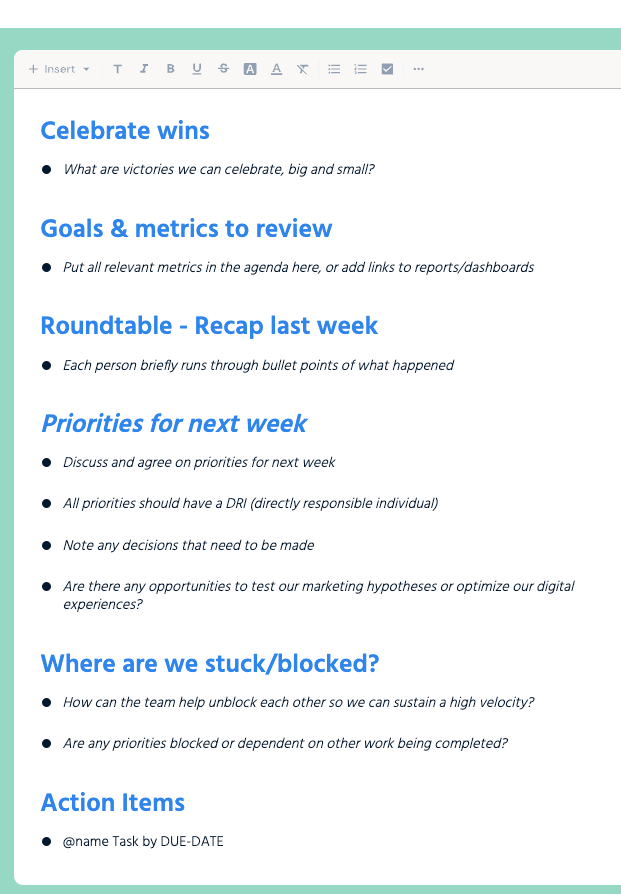

Use this marketing meeting agenda to bring your marketing department together to celebrate wins, align on goals, and identify project blockers.

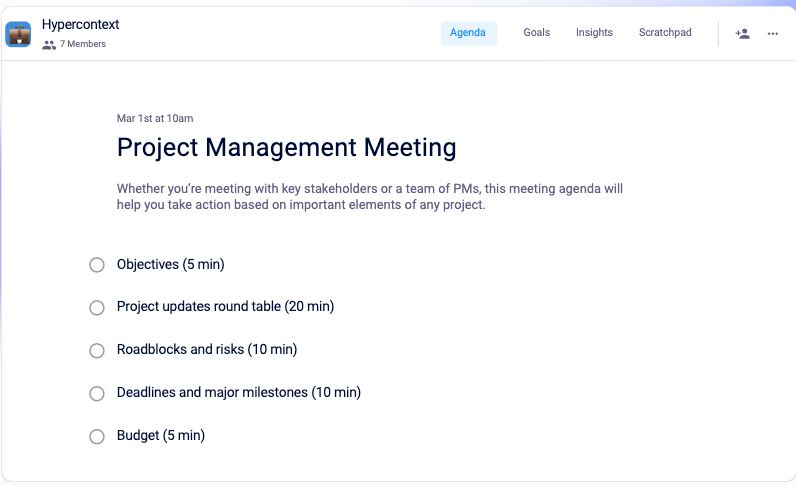

This project management meeting agenda template will help you identify objectives, risks, and deadlines for your next team project.

When it comes to planning a meeting, creating a thorough and well-organized agenda is crucial for ensuring that the meeting runs smoothly and achieves its objectives. Here are some of the key beneficiaries of using a meeting agenda:

- Project Managers: Project managers often have to lead team meetings and having a well-planned agenda helps them to stay on track, cover all necessary topics, and keep the meeting focused.

- Project Status Meeting Agenda

- Project Coordinators Meeting Agenda

- Lessons Learned Meeting Agenda

- Post Mortem Meeting Agenda

- Leadership Teams: Meeting agendas are also beneficial for leadership teams, such as executive boards or management teams. They can help to ensure that important topics are discussed, decisions are made efficiently, and everyone is on the same page with regards to company goals and strategies.

- Leadership Offsite Meeting Agenda

- Executive Leadership Meeting Agenda

- Board of Trustees Meeting Agenda

- Executives Meeting Agenda

An effective meeting agenda will make team collaboration seem like a cakewalk.

And when collaboration becomes easy, your team can focus on amping up their productivity and getting their creative juices flowing.

With the help of a project management tool like ClickUp, writing effective meeting agendas and managing meetings are easier than ever!

ClickUp lets you document every meeting, manage agendas, take down effective meeting minutes , assign comments to your team, and so much more.

Ready to watch your team ace teamwork and hit all their objectives?

Get ClickUp for free today and say goodbye to meeting disasters. 👋

Questions? Comments? Visit our Help Center for support.

Receive the latest WriteClick Newsletter updates.

Thanks for subscribing to our blog!

Please enter a valid email

- Free training & 24-hour support

- Serious about security & privacy

- 99.99% uptime the last 12 months

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of agenda in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- Perhaps we could move on to discuss the next item on the agenda.

- Has everyone received a copy of the agenda for next week's meeting ?

- Let's move on, or we will not have time to cover everything on the agenda.

- The agenda should include an item headed 'Any other business '.

- Action to prevent the spread of the disease is high on the government's agenda.

- business plan

- make time idiom

- set the agenda idiom

- slot someone/something in

- social calendar

- spread something over something

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

agenda | Intermediate English

Agenda | business english, examples of agenda, collocations with agenda.

These are words often used in combination with agenda .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of agenda

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

have irons in the fire

to be involved with many activities or jobs at the same time or to make certain that there are always several possibilities available

Binding, nailing, and gluing: talking about fastening things together

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun

- Intermediate Noun

- Business Noun

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

Add agenda to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Agenda vs. Itinerary — What's the Difference?

Difference Between Agenda and Itinerary

Table of contents, key differences, comparison chart, primary purpose, context of use, flexibility, typical components, compare with definitions, common curiosities, can an agenda be used for travel planning, is every trip or tour accompanied by an itinerary, is an agenda limited to professional settings, what is the main purpose of an agenda, how are agenda and itinerary different in terms of flexibility, do agendas always follow a strict format, can an itinerary include reservations and ticket details, how does an itinerary function, how do i create an effective itinerary, should an itinerary be strict or flexible, how do i ensure all essential points are on an agenda, can an itinerary also refer to a historical record of places visited, in what scenarios are both agenda and itinerary used simultaneously, are digital itineraries popular, what's the plural form of agenda, share your discovery.

Author Spotlight

Popular Comparisons

Trending Comparisons

New Comparisons

Trending Terms

Agenda vs Itinerary: Difference and Comparison

Planning has always served as an advantage before executing anything. It is good if all the factors have been taken into consideration before the actual actions as it prepares you for the worse situation.

And this is not only in businesses or the corporate world, but in general life also, planning is always good.

For example, before cooking a meal, it is good to plan where the ingredients are to be bought, what else is required, how much time it can take, etc.

Words, Agenda, and itineraries are both essential elements of planning what is needed. Both are made before the actual action to plan everything that must be done.

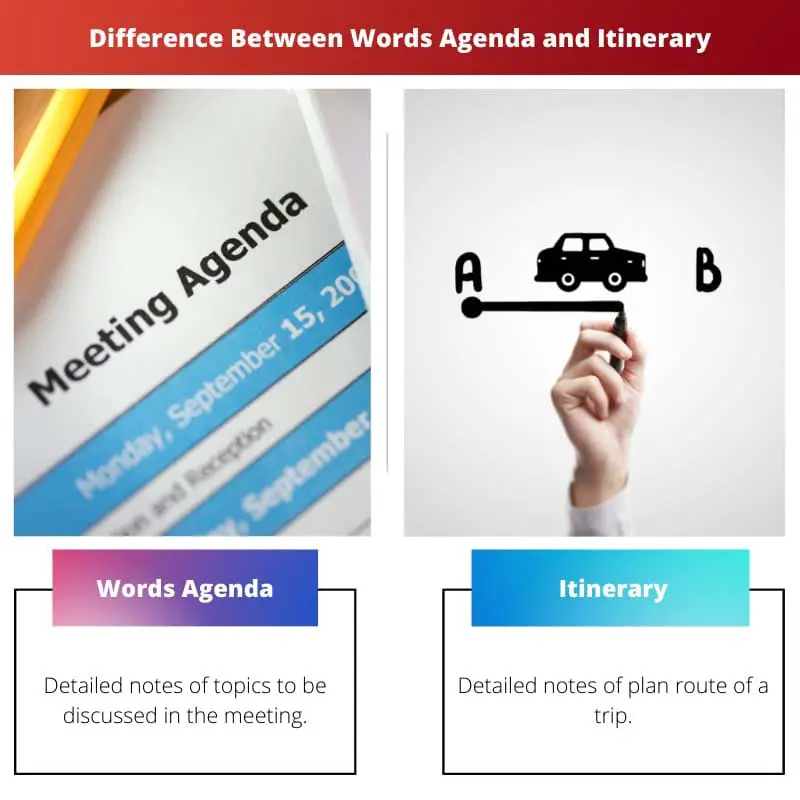

Key Takeaways Agenda is a list of items to be discussed or accomplished during a meeting or event, while an Itinerary is a planned route or schedule of a trip. The agenda is more focused on the content and goals of the meeting or event, while Itinerary is more focused on the travel arrangements and activities of the trip. Agenda is shorter and more straightforward than itineraries, which can include detailed information about transportation, accommodations, and sightseeing.

Words Agenda vs Itinerary

An agenda connotates to keeping a list of important things to be done the next day or important meetings for discussion. An itinerary is a calendar of occasions and activities associated with a preplanned tour. An itinerary assist in organizing an entire business tour, highlighting every next event in order.

Similar Reads

- Agenda vs Minutes: Difference and Comparison

- Notice vs Agenda: Difference and Comparison

Words agenda is a document that carries the information about any meeting and is distributed in advance or before the meeting starts and is always written in the future tense.

It is prepared by the secretary , and after confirming it with the chairman, it is distributed among all the members.

The Itinerary is a document containing all the information about the trip, especially the routes, and it is distributed among the travelers before or at the beginning of the trip.

A travel agent who is taking care of the trip is responsible for making and distributing it.

Comparison Table

What is words agenda.

It is a detailed note of all the content that must be considered in a meeting.

Things that Words Agenda has:

- Topics/subjects for discussion: All discussion topics must be precisely mentioned in the Words Agenda.

- Date and Time: date and time of the meeting should be mentioned at the top.

- Name of the Members: name of every member that’ll be attending the meeting should also be there in the Word Agenda.

Importance of agenda

- It explains the main objective and the main purpose of the meetings. Knowing the purpose before the meeting is important so that every member knows what they are aiming at and work to accomplish that objective.

- It gives time to search and collect all the knowledge of the objectives that have to be achieved. Knowing the consequences and risks in advance is always beneficial, so all the precautions should be discussed during the meeting only.

- It maintains the focus and motivates them to make the right decisions.

- One of the main reasons behind making Word Agenda is that it will help make the minutes.

It is always written in the future tense as it is written before the actual meeting.

What is Itinerary?

It is detailed notes of travel routes given to travelers by the travel agent. The importance of Itinerary are:

- Manages the time: it is useful in managing time as it has information about the travel routes and other important details. And it is important that time is not wasted. Otherwise, important things or views are left.

- Expenditure Control: you can control your expenditure as it will give you all the costs that you can incur; therefore, planning should be done accordingly.

- Easy and adventurous travel: it leads to the termination of all the worries related to travel so that you can enjoy the trip wholeheartedly.

- Check the trip essentials: an itinerary includes every want and requirement of the trip; therefore, you can always check if anything is left out or not. It will be very useful while packing.

The element of an effective Itinerary includes:

- Tour Program: this includes all the routes and different activities that’ll be taking place during the travel.

- Timetable: under this, there must be proper timing for the activities of the trip.

- Destination and duration: the entire destination and its duration.

Except for all the mentioned, there are 4 As that should be included while making an Itinerary. They are Attractions, Amenities, Accommodations, and Accessibility. Therefore, these are very important from a traveler’s point of view and must be included in Itinerary.

Main Differences Between Words Agenda and Itinerary

- Word Agenda is prepared to spread the details of a meeting, while Itinerary is prepared to tell the details of the trip or travel plan route.

- Word Agenda is prepared by the Secretary and approved by the Chairman, but a travel agent prepares an Itinerary.

- Word Agenda is important as it is used for the details of the meeting while Itinerary is important as it is used for route information of the travel.

- The Word agenda is associated with official meetings, while Itinerary is associated with travels.

- Word Agenda is prepared before the meetings start and then distributed among the members joining the meeting, whereas Itinerary is made before the trip and circulated among the travelers.

- https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=yP0C_1SoK8cC&oi=fnd&pg=PT61&dq=words+agenda&ots=XVBnS0b2T9&sig=VfW6ZhSiWfdrp2UUK3zJ43o-zQ4

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/014198798329991

Last Updated : 18 June, 2023

I’ve put so much effort writing this blog post to provide value to you. It’ll be very helpful for me, if you consider sharing it on social media or with your friends/family. SHARING IS ♥️

Chara Yadav holds MBA in Finance. Her goal is to simplify finance-related topics. She has worked in finance for about 25 years. She has held multiple finance and banking classes for business schools and communities. Read more at her bio page .

Share this post!

24 thoughts on “agenda vs itinerary: difference and comparison”.

The contrasts and insights provided in the post regarding an agenda and an itinerary are highly enriching. It’s an informative piece that accentuates the importance of adequate planning and organization in achieving successful outcomes.

Absolutely, Melissa. The article offers an in-depth understanding of planning and organizing, providing valuable guidance for anyone looking to enhance their planning skills and understanding.

I found the comparison between agenda and itinerary very enlightening. The clear explanations in the post exhibit the importance of thorough planning and organization in various scenarios.

Indeed, Rob. The article provides valuable insights into the details of planning and organizing, not just in businesses but in general life as well. This is an excellent guide.

This article illustrates the importance of planning for better execution. The comparisons between an agenda and an itinerary provide valuable insights into the significance of organizing and strategizing.

Absolutely. The distinction between an agenda and an itinerary is clearly explained in the post, emphasizing the importance of thorough planning for various scenarios.

I’m in complete agreement, Cpowell. The post is an informative guide and enhances the understanding of effective planning and organization. It’s an essential piece for anyone seeking to sharpen their planning skills.

The detailed comparison between an agenda and an itinerary in this post is enlightening. It underscores the significance of planning and organizing for effective outcomes across different situations and tasks.

Indeed, Lgraham. The comparisons and insights provided in the article bring to light the critical role of planning and preparedness, whether for meetings or travel.

This article serves as a great guide in understanding the distinction between an agenda and an itinerary. Both are crucial in ensuring better organization and management of tasks and events.

I absolutely agree with you Jeremy. The information in the post highlights the importance of planning and details in tasks, meetings, and travel.

The post offers comprehensive information that draws a clear line between an agenda and an itinerary. It emphasizes the significance of planning and preparedness, not just in business settings but also in daily life.

Indeed, Lisa. Planning is a crucial element in order to achieve success. This post provides an insightful comparison between agenda and itinerary and how they can be effectively utilized.

I completely agree. The details in the post about the importance of planning and organization are invaluable for anyone who is looking to understand how to effectively structure their tasks and events.

The comparison between agenda and itinerary in this post is very insightful. The detailed explanations give a clear understanding of the role of each in planning and execution.

I couldn’t agree more, Teagan. This article is definitely an enriching read and provides valuable insights for those aiming for effective planning and execution of their tasks.

Absolutely Teagan. I find the information in this post relevant and highly informative. It underscores the importance of proper organization in different aspects of life and work.

This article provides an excellent explanation of the differences betweeen agenda and itinerary. Reading through this post makes me realize the importance of planning and organizing for better outcomes.

Precisely, Cooper. The article is well-written and full of valuable points. By planning, we are able to anticipate risks and consequences and make the right decisions.

The post does an exceptional job in explaining the differences between an agenda and an itinerary. It has certainly enhanced my understanding of the importance of planning in achieving successful outcomes.

I completely agree. The post is extremely informative and serves as an excellent source of knowledge for understanding the significance of adequate planning, whether for meetings or travel.

Absolutely, Sally. The details and comparison provided in this article shed light on the crucial aspects of planning and organization. It’s an insightful read for anyone looking to enhance their planning skills.

The post delivers a detailed and insightful comparison of an agenda and an itinerary, emphasizing the importance of planning in various contexts. It’s an enriching read for understanding the role of planning in effective execution.

I completely agree, Sarah. The post is packed with valuable comparisons and detailed explanations, highlighting the significance of planning and organization in meeting objectives across different scenarios.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.