Geology Trips Tours and Holidays with GeoWorld Travel

Geology tours and holidays, scenery explained.

James Cresswell, Founder

GeoWorld Travel offers geology trips, tours and holidays to the world's most interesting geosites. Most geotours are led by GeoWorld Travel's founder, James Cresswell, as small group road trips for between 4 and 20 participants. Many of our geology trips visit Geoparks, National Parks, and World Heritage Sites, and can be searched for by the geological features they visit. No prior geological knowledge is required on these geology tours, and they will appeal to everyone from beginners to experts alike. On a GeoWorld Travel geology holiday the landscape is explained in an accessible way and while the rocks, volcanoes, fossils and glaciers are the star attractions of the trips, there will also be stunning scenery accompanied by incredible wildlife and fascinating human stories. GeoWorld Travel additionally places people on polar expedition cruises through our PolarWorld Travel website. “Geologising in a volcanic country is most delightful; besides the interest attached to itself, it leads you into most beautiful and retired spots." Charles Darwin, 1876

Destinations

CANARY ISLANDS

ENGLAND & WALES

SHETLAND ISLANDS

South Africa

SWITZERLAND

Wales Day Trips

Unsubscribe from our mailing l ist

Climate Change

GeoWorld Travel takes its environmental responsibilities very seriously, and offsets the carbon generated by our trips through our partner 'Carbon Footprint'. - More info

Financial protection.

The Package Travel and Linked Travel Arrangements Regulations 2018 require travel companies to provide security for the monies that UK consumers pay for certain types and combinations of travel arrangements booked with them and for consumers’ repatriation in the event of their insolvency. We provide this protection for our package arrangements by way of a trust account administered by independent trustees, Serenity Travel Trusts https://serenitytrusts.co.uk/for-consumers/ All money that you pay to us for package travel arrangements must be paid into a separate and designated bank account over which Serenity are appointed as trustee and we can not access the funds until you have completed your travel. If you book arrangements other than a package, your monies will not be financially protected. Please ask us for further details.

*Trips that are nearly full or are already full are indicated below*

England & wales, jurassic coast & the complete geologic timescale , 15 - 27 april 2024 *full*, april/may 2026 (dates tbc), northern namibia, a geological safari, 30 may - 12 june 2024 *full*, 29 may - 11 june 2025 *12 spaces*, the birth of geology, 10 - 18 june 2024 *full*, 29 may - 6 june 2025 *full*, shetland islands, a tectonic jigsaw, 18 - 22 june 2024 *full*, june 2025 ( dates tbc ), switzerland, an alpine adventure, 9 - 18 july 2024 *full*, june/july 2026 ( dates tbc ), the vulcanologist's dream, 3-11 september 2024 *full*, 24 june - 2 july 2025 *full*, southern namibia, diamonds, canyons and fossils, 3 - 17 september 2024 *9 spaces*, august/september 2025 (dates tbc), the classic volcanoes, 1-9 october 2024 *full*, september/october 2026 ( dates tbc ), trilobite's sahara kingdom, 11 - 21 november 2024 *full*, 10 - 20 november 2025 *14 spaces* , ocean crust and mountains of mantle , 21 - 30 january 2025 *5 spaces*, volcanoes & famous fossil sites, 3 - 11 april 2025 *full*, yellowstone, dinosaurs & grand canyon, 16 - 27 september 2025 *full*, the roof of the world, october 2025 ( dates tbc ), canary islands, volcanic island hoppi ng, 8 - 16 december 2025 *12 spaces*, spitsbergen & north-east greenland, 2026 ( dates tbc ), antarctic + arctic, multiple trips and departure dates - please contact us for details.

Geotourism is defined as tourism that sustains or enhances the distinctive geographical character of a place—its environment, heritage, aesthetics, culture, and the well-being of its residents.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

What is geotourism and why is it important?

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Geotourism is a term that I hear more and more these days, yet not many people really know what it means! So here at Tourism Teacher I am going to tell you all about the concept of geotourism, what it means and why it is so important in today’s tourism industry.

What about geography?

A note on defining geotourism, what is the difference between geotourism and ecotourism, geotourism examples, the benefits of geotourism, the disadvantages of geotourism, geographical geotourism destinations, geological geotourism destinations, geotourism- further reading, what is geotourism.

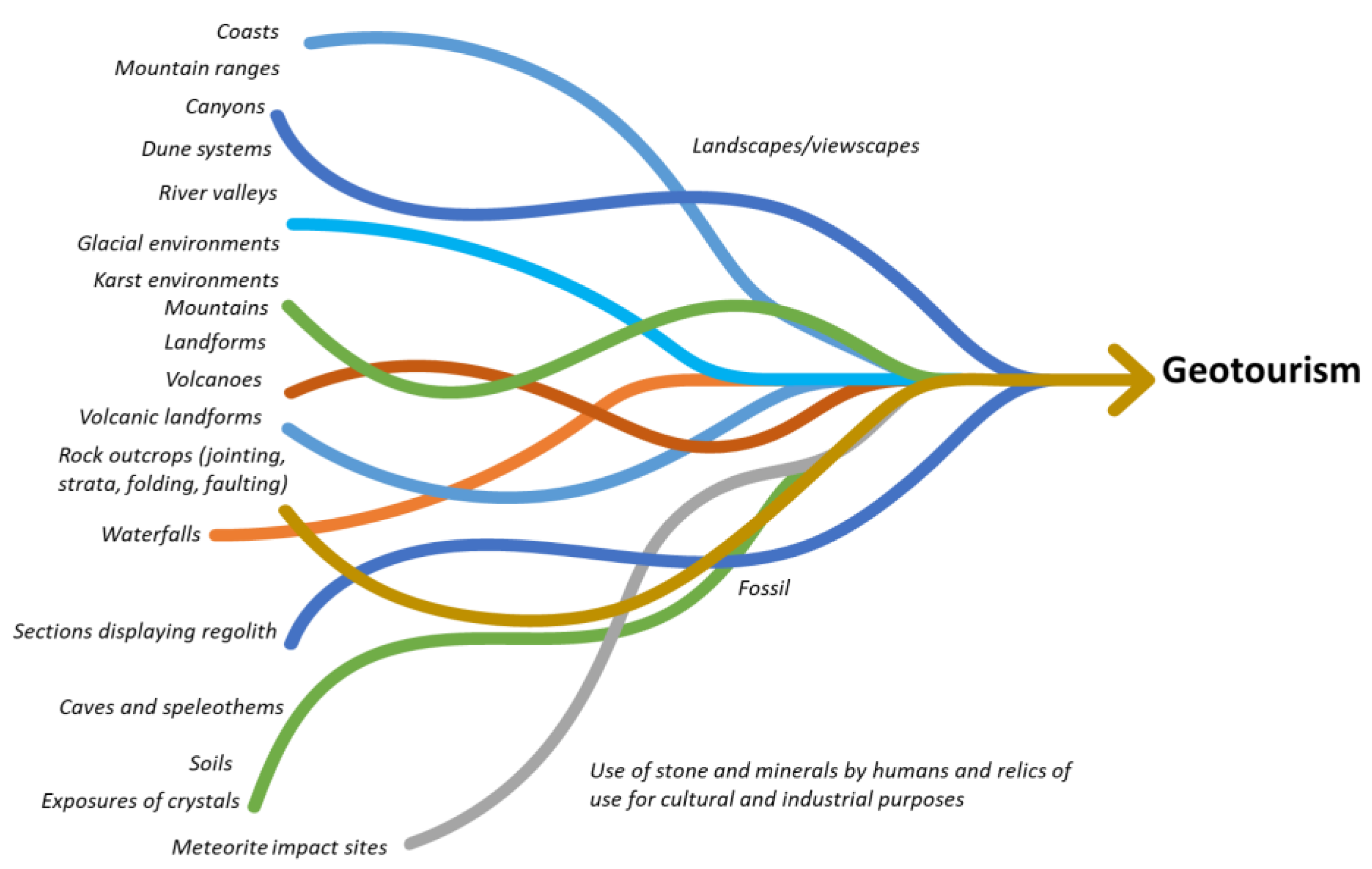

Geotourism is a tricky one to define. One way of looking at it is as the term for ‘geological tourism’. To break that down, let’s first look at what geology is. This is the study of the structure, dynamics and evolution of the Earth itself, as well as its natural and mineral energy resources. It is all about examining the processes that have made the planet what it is today.

So, how does that fit into tourism? Geotourism is generally about visiting sites or areas of geological importance. In their book Handbook of Geotourism , Dowling and Newsome define geotourism as follows:

Geotourism is tourism based on geological features. Over time it has been variously described as being a type of tourism that is either ‘geological’ or geographical’ in orientation. Whereas the former view was that geotourism was a ‘type’ of tourism in a similar vein to ecotourism, the latter view was wider and encompassed it thereby representing a new ‘approach’ to tourism. Over a decade ago we espoused the former view that geotourism is a niche form of natural area tourism based on geology and landscape. Four years later we added to the definition by suggesting the fact that geotourism could be undertaken through either ‘independent visits’ or ‘guided tours’ to geological features.

Another , simpler, definition is simply ‘Tourism that sustains or enhances the geographical character of a place – its environment, culture , aesthetics, heritage, and the well-being of its residents’ . This has much less of a science-led focus, and can be applied to anywhere rather than geologically important areas… However, this is the definition used by National Geographic. As such, it relates to geography rather than geology. A long-buried quote from Nat Geo says that:

Geography –from which ‘geotourism’ derives– is not just about where places are. It’s also about what places are. It’s about what makes one place different from the next. That includes not only flora and fauna, which is the realm of ecotourism, but also historic structures and archaeological sites, scenic landscapes, traditional architecture, and locally grown music, cuisine, crafts, dances, and other arts.

As with many types of (or approaches to) tourism, there are varying definitions of geotourism. “What is geotourism?” is a difficult question to answer completely, as people have different views on the matter. The best we can do is look at the academic research behind the phenomenon, and see how that relates to real-world travel and tourism . Dowling and Newsome, quoted above, have done extensive research into what geotourism is and the impact it has on the industry. They go on to say:

By now the definition of geotourism had expanded to encompass a number of attributes – geology, tourism, geosites, visits and interpretation. The ‘geo’ or geology part of geotourism includes geological features or attributes which are considered worthy of tourist interest. The ‘tourism’ part refers to the conversion of geological features or attributes into tourism resources as ‘geo’ attractions or tours often at designated ‘geosites’.

However, the definition used by National Geographic tends to be the most popular one. It is succinct and easy to understand – and also has more of an impact (so perhaps more of an importance) than the geology-based term…

Geotourism is not the same as eco tourism . In fact, they are two very different things. Eco tourism tends to generally be more hands-on – beach clean ups, litter picking, conservation work and so on. The two types of tourism have been said to be ‘sisters’, in a way, with eco tourism more focused on nature and ecology instead of built environments.

Of course, it all depends on which definition of geotourism you feel is most correct. If we take the geographic definition above, which talks about sustaining and enhancing the geographical character of an area, then we do start to see similarities with eco tourism. In this case, however, there are still major differences. Eco tourism is more focused on nature – green spaces, the ocean , sustainability. Whereas geotourism encompasses the people, the culture, the cuisine and so much more.

There are many examples of geographic geotourism around the world. The Destination Center says that ‘ destination-stewardship leaders have taken a variety of ways to establish geotourism as a preferred strategy. The goal is to help develop a geotourism mindset—a constituency of stewardship—with corresponding protection of natural and cultural distinctiveness, economic benefits, and improved quality of life. ’

This type is about projects which help the community. They are self-aware in name and nature. This might be something like Lake Tahoe’s annual Geotourism Expo. The festival looks to restore the character of a recreational destination which has been long-dominated by generic resorts. Fogo Island, Newfoundland, is also using geotourism in order to reinvent itself as a cultural centre and retreat for artists. To do so it is adapting food, design and materials which are distinctive to this area.

But if we look at Newsome and Dowling’s version, examples differ. There are many sites of geological importance and interest around the world! West Coast Fossil Park in South Africa , for example, is a beautiful geology-based tourist site you can visit. Here you can see ancient fossils and gain some perspective of history. Other geological sites, like caves, craters and waterfalls , are beautiful as well as really interesting. Geotourism in this sense goes beyond just appreciating the aesthetic of a place…

There are many benefits to both types of geotourism. With Newsome and Dowling’s geological version, the educational tourism opportunities are vast. You can learn a lot more about geology by visiting sites of geological importance than you can do in a classroom. By visiting the Undara Lava Tubes in Australia , for example, you can understand more about the effects of lava on the ecosystem.

With the other (geographical) approach, we can also see vast benefits. The whole point is that it enhances or sustains an area and the culture/cuisine/heritage/environment and so on. To this end, it is no surprise that geotourism is seen as a good thing! It ploughs money into local causes and communities, while improving an area so that future generations can visit and enjoy too. It teaches visitors about tourist responsibility, and also protects the heritage of an area – meaning locals can have pride in where they are from. There is also a real sense of community spirit with geotourism projects!

It is hard to see the disadvantages of either type of geotourism. With our geographic type, everything is so totally focused on the improvement of an area or at the very least enhancing what is already there. Money is going to local people and local businesses, and visitors are able to enjoy a place knowing that they are supporting a community. The only issue with this might be a ‘white saviour’ complex of sorts for tourists visiting destinations that are perhaps still developing. I have spoken about this previously in my article regarding slum tourism !

When it comes to the geology type of geotourism, issues can occur with people visiting sites that are particularly delicate. However, if tourists are responsible and respectful when visiting this type of location then there are few disadvantages to geotourism. Geological sites are interesting and provide an insight into how the planet works – people learning about this is definitely a good thing.

Destinations

I’ll split this section in two again – one for geographical and one for geological destinations!

These are destinations that are part of the National Geographic geotourism content marketing platform. They are supported by Nat Geo, providing a “platform for destinations to inventory and promote the places that locals most respect and recommend, in partnership with National Geographic.” The list below is not exhaustive – just some great examples of their destinations and projects!

- Tennessee River Valley

- Heart of the Continent : Northeast Minnesota and Northwest Ontario

- Bay Islands in the Bahamas : Utila, Roatan, and Guanaja

- Tibet & the Himalayas

- Teton Geotourism Center, Driggs, Idaho

- Fogo Island, Newfoundland

- The Hurtigruten cruise ship fleet

- The GeoWisata project in Bogor, Java, Indonesia

It should be said that Nat Geo are no longer adding new destinations to this platform, following their acquisition by Disney.

Below you’ll find a list of fascinating destinations. These are all sites of some geological importance or interest.

- Faial’s Badlands, the Azores, Portugal

- Aletsch Glacier, Valais, Switzerland

- Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky

- El Teide, Tenerife

- Mingsha Singing Sand Dunes, Dunhuang, China

- The Matterhorn, Switzerland

- Hunstanton Cliffs, Norfolk , UK

- Meteor Crater in Arizona

- Niagara Falls, New York

- Siwalik Fossil Park, India

If you enjoyed this article I am sure that you will love these too!

- Ecotourism: Everything you need to know

- What is sustainable tourism and why does it matter?

- The Best Eco Lodges in the World

- What is responsible tourism and why does it matter?

- Agritourism: What, where and why

Liked this article? Click to share!

- Scholarly Community Encyclopedia

- Log in/Sign up

Video Upload Options

- MDPI and ACS Style

- Chicago Style

Geotourism is a form of nature tourism that provides a more immersive experience by exploring the geological richness of the destination. In their natural form or explored as thermal springs and spas, landscape elements and geological formations offer visitors a richer and more holistic experience.

1. Introduction

2. Motivation Factors in Volcanic Tourism

- Dowling, R. Global geotourism—An emerging form of sustainable tourism. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 59–79.

- Dowling, R.; Newsome, D. Handbook of Geotourism; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018.

- Dowling, R. Geotourism’s Global Growth. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 1–13.

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.; Leung, Y.-F. The nature and management of geotourism: A case study of two established iconic geotourism destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 2, 19–27.

- Mikhailenko, A.V.; Nazarenko, O.V.; Ruban, D.A.; Zayats, P.P. Aesthetics-based classification of geological structures in outcrops for geotourism purposes: A tentative proposal. Geologos 2017, 23, 45–52.

- Dowling, R.; Allan, M.; Grünert, N. Geological Tourist Tribes. In Consumer Tribes in Tourism; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 119–136.

- Suhud, U.; Allan, M. Exploring the impact of travel motivation and constraint on stage of readiness in the context of volcano tourism. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 927–934.

- Bird, D.; Gísladóttir, G. Southern Iceland: Volcanoes, tourism and volcanic risk reduction. In Volcanic Tourist Destinations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 35–46.

- Ruban, D.A. Geotourism—A geographical review of the literature. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 15, 1–15.

- Moufti, M.; Németh, K. The intra-continental Al Madinah Volcanic Field, Western Saudi Arabia: A proposal to establish Harrat Al Madinah as the first volcanic geopark in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Geoheritage 2013, 5, 185–206.

- Allan, M. Toward a Better Understanding of Motivations for a Geotourism Experience: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Ph.D. Dissertation, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Australia, 2011.

- Soliman, M.S.; Abou-Shouk, M.A. Predicting behavioural intention of international tourists towards geotours. Geoheritage 2017, 9, 505–517.

- Prendivoj, S.M. Tailoring signs to engage two distinct types of geotourists to geological sites. Geosciences 2018, 8, 329.

- Aquino, R.S.; Schänzel, H.A.; Hyde, K.F. Analysing push and pull motives for volcano tourism at Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 177–191.

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R. The scope and nature of geotourism. Geotourism 2006, 3, 25.

- Garofano, M. Geotourism in the Azores: Considerations about a Decade Experience. 2014. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/43296429/Geotourism_in_the_Azores_Considerations_20160302-6269-fsdpkc.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Garofano, M. Geowatching, a term for the popularisation of geological heritage. Geoheritage 2015, 7, 25–32.

- Heggie, T.W. Geotourism and volcanoes: Health hazards facing tourists at volcanic and geothermal destinations. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2009, 7, 257–261.

- Erfurt-Cooper, P.; Cooper, M. Volcano and Geothermal Tourism: Sustainable Geo-Resources for Leisure and Recreation; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010.

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013.

- Szepesi, J.; Harangi, S.; Ésik, Z.; Novák, T.J.; Lukács, R.; Soós, I. Volcanic geoheritage and geotourism perspectives in Hungary: A case of an UNESCO world heritage site, Tokaj wine region historic cultural landscape, Hungary. Geoheritage 2017, 9, 329–349.

- Bird, D.K.; Gisladottir, G.; Dominey-Howes, D. Volcanic risk and tourism in southern Iceland: Implications for hazard, risk and emergency response education and training. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2010, 189, 33–48.

- Erfurt-Cooper, P. Volcanic Tourist Destinations; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2014; p. 379.

- Adedoyin, F.; An, H. Smart tourism via digital governance: A case for Jeju volcanic island and lava tubes. J. Tour. Hosp. Sports 2017, 31, 26–39.

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897.

- Kislali, H.; Kavaratzis, M.; Saren, M. Rethinking destination image formation. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10.

- Ren, C.; Blichfeldt, B.S. One clear image? Challenging simplicity in place branding. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 11, 416–434.

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.B. The meaning and measurement of destination image. J. Tour. Stud. 1991, 2, 2–12.

- Borges-Tiago, M.T.; Arruda, C.; Tiago, F.; Rita, P. Differences between TripAdvisor and Booking.com in branding co-creation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 380–388.

- Kim, S.-E.; Young, K.; Shin, L.I.; Yang, S.-B. Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: The case of Sina Weibo. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 687–702.

- Buhalis, D. Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75.

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623.

- Robertson, M.H. Heritage interpretation, place branding and experiential marketing in the destination management of geotourism sites. Transl. Spaces 2015, 4, 289–309.

- Chung, N.; Leeb, H.; Lee, S.J.; Koo, C. The influence of tourism website on tourists’ behavior to determine destination selection: A case study of creative economy in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 96, 130–143.

- Költringer, C.; Dickinger, A. Analyzing destination branding and image from online sources: A web content mining approach. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1836–1843.

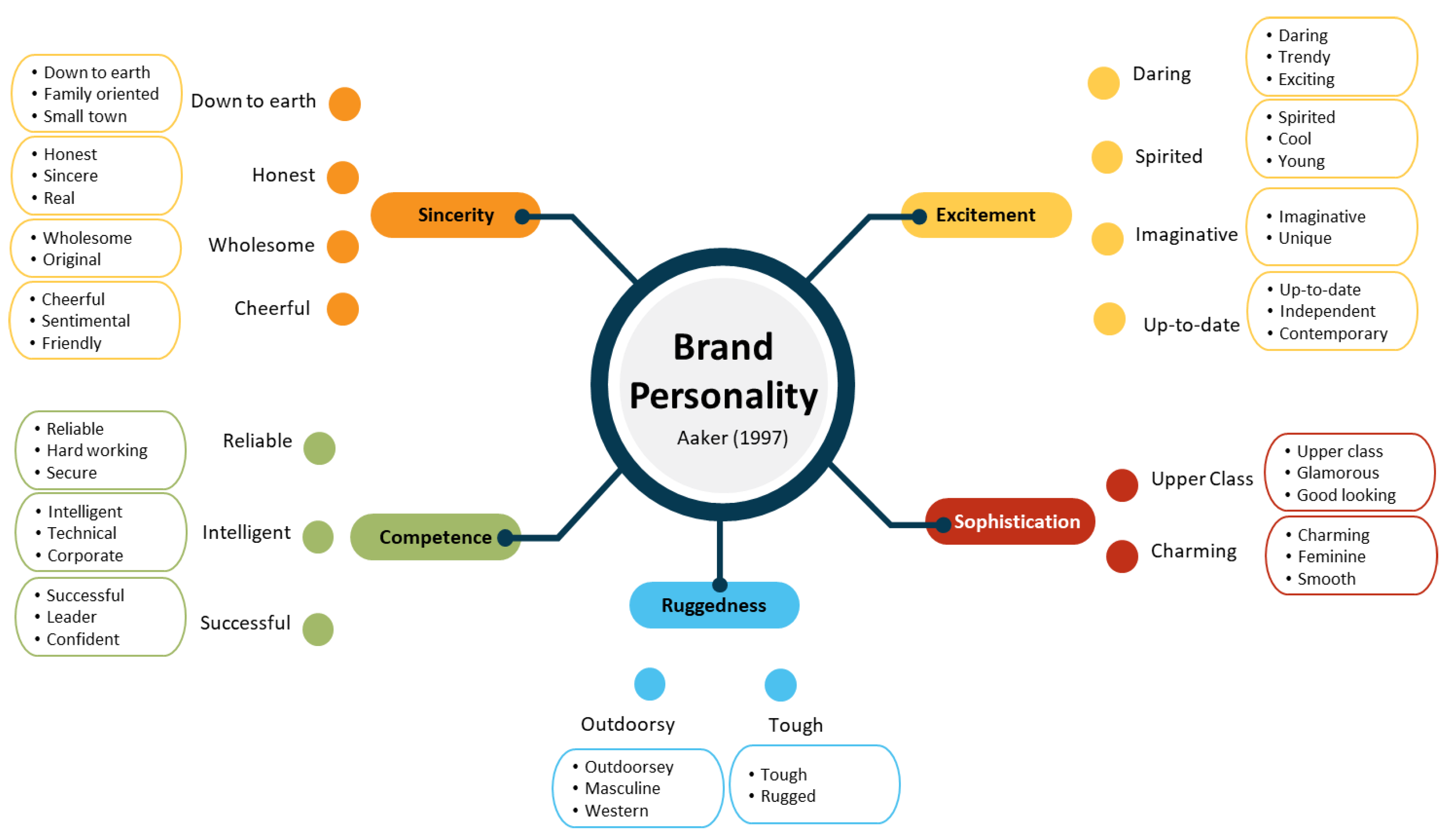

- Dickinger, A.; Lalicic, L. An analysis of destination brand personality and emotions: A comparison study. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2016, 15, 317–340.

- Yousaf, A.; Amin, I.; Gupta, A. Conceptualising Tourist Based Brand-Equity Pyramid: An Application of Keller Brand Pyramid Model to Destinations. Tour. Hosp. Manag. Croat. 2017, 23, 119–137.

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of brand personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 347–356.

- Baloglu, S.; Henthorne, T.L.; Sahin, S. Destination image and brand personality of Jamaica: A model of tourist behavior. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 1057–1070.

- Ekinci, Y.; Hosany, S. Destination personality: An application of brand personality to tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 127–139.

- Murphy, L.; Moscardo, G.; Benckendorff, P. Using brand personality to differentiate regional tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 5–14.

- Kim, S.; Lehto, X.Y. Projected and perceived destination brand personalities: The case of South Korea. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 117–130.

- Vinyals-Mirabent, S.; Kavaratzis, M.; Fernández-Cavia, J. The role of functional associations in building destination brand personality: When official websites do the talking. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 148–155.

- Hanna, S.; Rowley, J. The projected destination brand personalities of European capital cities and their positioning. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 1135–1158.

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Advisory Board

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

- Download PDF

Geotourism is tourism based on geological features. It has been variously described as being a type of tourism that is either ‘geological’ or geographical’ in orientation. Whereas the former view was that geotourism was a ‘type’ of tourism in a similar vein to ecotourism, the latter view was wider and encompassed it thereby representing a new ‘approach’ to tourism. In this chapter geotourism is viewed both as a ‘type’ of tourism (with a geological focus) as well as an ‘approach’ to tourism, encompassing a wider geographic view. Thus, it is proposed that geotourism may be viewed through multiple lenses along a geological spectrum which has geotourism as a ‘type’ of tourism at one end, and as an ‘approach’ at the other. Thus, the definition of geotourism has expanded to encompass a number of attributes – geology, tourism, geosites, visits and interpretation. The ‘geo’ or geology part of geotourism includes geological features or attributes which are considered worthy of tourist interest. The ‘tourism’ part refers to the conversion of geological features or attributes into tourism resources as ‘geo’ attractions or tours often at designated ‘geosites’. These can occur in either natural or modified settings such as in rural or urban areas and visits to geological attractions (geo-attractions) could be either independent or on guided tours. The interpretation of geo-attractions occurs through an approach comprising elements of both geology and tourism. The geological elements comprise ‘form’, ‘process’ and ‘time’. These describe the geological tourist attractions of landscape, landform or feature (that is, its form), how it got there or was made (process), and when, or during what period of geological time, it was formed (time).

Table of Contents

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Slovenščina

- Science & Tech

- Russian Kitchen

Moscow metro to be more tourist-friendly

A new floor sign system at the Moscow metro's Pushkinskaya station. Source: Vladimir Pesnya / RIA Novosti

For many years now, Moscow has lagged behind St. Petersburg when it comes to making life easy for tourists, especially where getting around the city is concerned. Whereas the northern capital installed English-language maps, signs and information points throughout its subway system in the late 2000s, the Russian capital’s metro remained a serious challenge for foreign visitors to navigate.

Recent visitors to Moscow may have noticed some signs that change is afoot, however. In many stations of the Moscow subway, signs have appeared on the floor – with large lettering in Russian and English – indicating the direction to follow in order to change lines. Previously, foreign visitors using the Moscow metro had to rely solely upon deciphering the Russian-language signs hanging from the ceilings.

Student volunteers help tourists find their way in Moscow

However, this new solution has a significant drawback. “The floor navigation is visible only to a small stream of people – fewer than three people per meter. During peak hours, this navigation will simply not be noticed,” said Konstantin Trofimenko, Director of the Center for Urban Transportation Studies.

One of the biggest problems for tourists in the Russian capital remains the absence of English translations of the names of subway stations in the station vestibules and on platforms. The Department of Transportation in Moscow has not commented yet as to when this problem will be solved. However, Latin transliterations of station names can already be found in the subway cars themselves.

Finding the right exit

At four of the central stations – Okhotny Ryad, Teatralnaya, Ploshchad Revolyutsii, Lubyanka and Kuznetsky Most – the city authorities have now installed colorful stands at the exits with schematic diagrams of the station’s concourse and surrounding area, which provide information about the main attractions and infrastructural facilities.

The schematic diagrams are the work of British specialists from the City ID and Billings Jackson Design firms, who have already implemented successful projects in New York and London.

According to Alexei Novichkov, expert at the Design Laboratory at the Higher School of Economics, the design of these information booths raises no objections: The color solutions, font, layout and icons are consistent with international standards.

However, the stands do have some shortcomings. “Many questions are raised about the fact that the developers of these maps did not apply orientation to the north, and have provided layouts of the surrounding areas with respect to the exits,” says Novichkov. “A system like that is used for road navigators, but most of the ‘paper’ guides and maps are oriented strictly to north. The subway map is also oriented to north, so people may become confused.”

Muscovites and foreign visitors are generally positive about these navigation elements, with most of them citing the numbered exits from the subway as the most useful feature.

The fact is that many Moscow subway stations have several exits. One of the busiest central stations of the Moscow subway in particular, Kitay-Gorod, has more than a dozen exits. Previously, these exits were differentiated from each other only with signs in Russian referring to the names of streets and places of interest to which they led – making it easy for tourists and those with poor navigation skills to get confused.

Now, when making an appointment to meet a friend, instead of struggling to find the right spot when they tell you: “I'll meet you at the exit to Solyanka Street,” you can just propose to meet under a specific exit number.

“I’ve lived in Moscow for seven years,” says Angelika, a designer from Voronezh, “but I still don’t always know where to go to find the place I need, so the new schematic diagrams will be very useful. Previously, some subway stations had maps, but not with so much detail.”

Teething problems

Foreigners, meanwhile, focus their attention on other elements. “It is good that the new information boards have QR-codes, which can be ‘read’ by smartphones,” says Florentina, a writer from Vienna. But there are also shortcomings. “The English font of the information on posters and in the captions to theaters and museums is too small – you have to come very close to see it well,” she says.

Pleasant encounters on the streets of Moscow

Florentina was also dissatisfied with the fact that such posters are not provided at all subway stations: “When I was trying to find Tsaritsyno Park (a museum and reserve in the south of Moscow) at a subway station with the same name, it turned out to be quite difficult,” she says.

“There are no maps with landmarks for other areas, such as those already in the city center. There were no clear pointers in the English language, and the passers-by I met did not speak in English, so they could not help me,” she adds.

Officials say that the navigation system is gradually being redeveloped and improved. According to Darya Chuvasheva, a press representative for the Department of Transport of Moscow, the introduction of a unified navigation system will take place in stages.

“By the end of 2014, the system will first appear on the first subway stations on the Circle Line. By the end of 2015, we plan to install the system at all major stopping points, subway stations and transport interchange hubs,” says Chuvasheva.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox

This website uses cookies. Click here to find out more.

Editorial: Geotourism and Geoconservation

- Published: 06 March 2012

- Volume 4 , pages 1–5, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Thomas Alfred Hose 1

4931 Accesses

41 Citations

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Welcome to this special issue of Geoheritage with its set of themed papers on ‘geotourism and geoconservation’. The authors of every paper have a combined practitioner and academic interest in understanding and promoting this important interrelationship, the pursuit of which avoids the ills of geo-exploitation (Hose 2007 ). There can be no doubt, as a pioneer in European geoconservation and geological outreach noted, that “Raising public awareness is the key to sustainable geoconservation success.” (Gonggrijp 2000 , p. 44). Geotourism has had a key role over the last decade or so in such promotional work and has undoubtedly made a major contribution to bringing geology to the attention of a greater number of the populace than was thitherto achieved. Geotourism is a relatively newly recognised but rapidly developing form of geology-based tourism. It was initially recognised and defined in the United Kingdom (UK) where it was also the first focus of dedicated university research (Hose 2003 ). Its first widely published definitions (Hose 1995 , 1997 , 2000 ) were specifically related to on-site interpretative provision for the purpose of geoconservation. These early definitions and the discussions around them also recognised the significant underpinnings provided to geotourism by social history and industrial archaeology, elements later included in most geopark developments. A new definition of geotourism, and the background behind its necessary development, is given in two of the papers (Hose, this volume; Hose and Vasiljević, this volume) herein presented.

As variously redefined and discussed in Europe and elsewhere over the past 15 years, geotourism has invariably had a geological basis and encompassed an examination of the physical basis, interpretation and promotion of geosites and geomorphosites. Two already published Australasian-based dedicated geotourism books (Dowling and Newsome 2006 ; Newsome and Dowling 2010 ) both adopted the geological basis of geotourism and supported the original approach adopted by Hose ( 1995 , 2000 ). Likewise, a recent major national inventory of geotourism resources for Iran (Amrikazemi 2010 ) has adopted and promoted the geological basis of geotourism; the Iran volume is also a fine example of how to present a country’s geoheritage as both an asset and something worthy of appreciation at a variety of scales in a readily understood local format. It also highlights, as do the two Australasian-based books, that modern geotourism and the discussion around it has spread far from its UK origins and been globally embraced.

Geotourism, as originally promoted, also encompasses geoscientists’ lives, work, collections, publications, artworks, field notes, personal papers, workplaces, residences and even their final resting places and monuments (Hose 1996 ). The linked geotourism themes of geoconservation, geohistory and geo-interpretation are updated (Hose, this volume) and the latter theme explored (Burek, this volume; Wrede and Muegge-Bartolovic, this volume) and especially evaluated (Crawford and Black, this volume; Moreira, this volume), in several of this issue’s papers. Geohistory is particularly examined in two papers (Gordon, this volume; Hose, this volume). At the outset of its inception, it was envisaged that geotourism would both constituency build and provide some funding for geoconservation when governments were unwilling (and now in these austere times conveniently suggesting themselves unable) to provide such financial support.

Geotourism was developed in the UK as consequence of the late 1980s recognition by school, university and museum geologists of the increasing losses of mines and quarries to unsympathetic after-uses and reclamation programmes. Natural geological exposures were also increasingly being lost due to unsympathetic civil engineering projects for major buildings, transport and coastal defence. Even long classic geology teaching sites were affected, and this was brought to this Guest Editor’s attention, stimulating the geotourism work, in an area he had partly field-mapped as an undergraduate and to which he later took geology student field parties. Over some 20 years, he witnessed in that area, the Crich inlier (Fig. 1 ) and the environs of the town of Matlock in the Peak District in England, the loss of major quarry sites to landfill (Figs. 2 and 3 ) and access restrictions into others on the grounds of health and safety; privacy concerns for new buildings with their private grounds in and around old quarries also reduced access. Consequently, many specific rock sequences and beds are now no longer exposed either in the district or anywhere else. It was perhaps only natural that the first published geotourism study (Hose 1994 ) was an assessment of the visitors to the National Stone Centre situated within 10 km of Crich and Matlock. Places such as the National Stone Centre, which is situated within a redundant limestone quarry, can stimulate an early and potentially lifelong interest in geology. Both extractive industry and natural exposure sites are the literal training grounds for student geologists, some of whom will go on in the future to recognise and provide the raw geological materials that sustain modern economies.

The Crich inlier in the Peak District of England: In this view, looking north-east from near Whatstandwell, the hill in the distance is the folded core of an inlier of Lower Carboniferous limestone of Visean series age. It is cut by a large working quarry and several redundant quarries; the floor of one redundant quarry houses The National Tramway Museum, established in 1959. The hill has been mined, probably since Roman times, for lead ore and its slopes are littered with numerous capped and uncapped mine shafts. The rocks surrounding the hill are Upper Carboniferous coarse-grained sandstones, mudstones and shales of the Millstone Grit Group of Namurian series age. Despite the extensive mining and quarrying of the area, its landscape still has considerable aesthetic appeal and attracts day visitors and tourists from the major towns, such as Derby and Nottingham, to the south of the Peak District (Copyright T.A. Hose)

St. Michael’s Quarry, Crich (in September 1986) during the first phase of landfill operations: Note the spire ( top left ) of the church which gave its name to this limestone quarry can be seen above the trees that hide the road running along the edge of the quarry. Before the landfill operation started, there was exposed at the foot of the large quarry face, in the Lower Carboniferous limestone of the Monsal Dale Limestone Formation (Visean series age), a fossil-rich coral bed now no longer seen anywhere in the district. The quarry was fairly accessible to geologists for many years via a steep path to the right in this view. During the landfill operations, geologists were denied access, and no ‘rescue’, in situ recording and collecting from strata now no longer easily accessible in the district was possible; a ‘window’ looking into deep time has been securely closed (Copyright T.A. Hose)

St. Michael’s Quarry, Crich (in November 2010) after its complete infilling: This view is from the road that runs alongside the church above the now completely buried cliff (seen in Fig. 2 ) of the former quarry. The quarry has been completely filled in, and the former slope of the hillside has been more or less restored to its original profile. Trees and shrubs have been planted to cover the landfill area. The only obvious remaining evidence left of the old quarry is the decaying fence and warning notice some 50 m away from the vantage point from which this photograph was taken (Copyright T.A. Hose)

Within Europe, similar concerns to those in the UK over the loss of geosites and geomorphosites led to the establishment in 1993 of The European Association for the Conservation of the Geological Heritage (ProGEO). Working through its member country and regional working groups, ProGEO has successfully developed and promoted geoconservation across Europe, especially through the GEOSITES project established in 1996. Its third international symposium, held in Madrid in 1999, led to the publication of a much cited and influential volume (Barretino et al. 2000 ) with contributions from acknowledged international authorities on geoconservation and geotourism. The emergence of the journal Geoheritage seems a natural but long overdue development from that and similar ProGEO publications. The world’s first dedicated geotourism conference, with international attendees and contributors, was held in the UK in Belfast in 1998 (Robinson 1998 ), but it did not publish any proceedings.

There were several geotourism conferences in Europe in the opening decade of this century, the last of which was Geotrends’10 held in Novi Sad, Serbia (Hose et al. 2011 ), and most of these published at least an abstracts volume. There have also been three so-called global geotourism conferences (in 2007, 2009 and 2011), but these have been mainly southern hemisphere events with limited contributions and influence from the key European geotourism academics. The present decade has witnessed a number of geotourism conferences, and 2012 alone already has in the calendar for May the ‘1st International Congress on Management and Awareness in Protected Volcanic Landscapes’ hosted within Spain's La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone Natural Park, and for October the ‘Appreciating Physical Landscapes: Geotourism 1670–1970’ geohistory conference hosted by the Geological Society of London in its Burlington House apartments that incidentally house one of the world’s finest geology libraries. It is to be hoped that both European conferences will publish a set of proceedings that will strengthen our knowledge and understanding of geotourism. Europe is also where the first journal dedicated to geotourism, Geoturystyka , was founded in Poland in 2004. The International Association for Geotourism, or IAGt, was also concomitantly founded in Poland, and there are also decidedly national geotourism organisations such as that established in Italy.

The main reason for the original UK development of geotourism was to promote and provide some funding for geoconservation (Hose 1995 , 2011 ). The development and management of such geoconservation strategies at a regional and national scale, that also support geotourism, have been pioneered in the UK and are described in the paper on Wales (Burek, this volume). The development of analytical empirical tools, at the scale of both individual sites and regional landscapes, for which the ability to collect, analyse and present complex data is becoming a necessary pre-requisite for good geoconservation management and geotourism site and area selection; an excellent example of some innovative work in this field is provided herein from Spain (Martín-Duque, García and Urquí, this volume). A geoconservation focus gives geotourism some overlap with other forms of natural heritage tourism such as ‘environmental’, ‘nature-based’ and ‘eco-tourism’. Possibly the major natural global geotourism interest is in cave tourism, although this can also be expanded to old mines and waterfalls. In this set of papers, the former are considered at the national scale for Italy (Garofano and Govoni, this volume) and the latter as case studies from Brazil (Moreira, this volume) and Scotland (Gordon, this volume), although the waterfalls considered lie at each end of the size spectrum. Both cave (and for that matter, mine) and waterfall tourism can be traced back to at least the seventeenth century in Europe (Hose 2008 ). However, volcanic geotourism has a history from at least the eighteenth century (Hose 2010 ), and the interpretation and presentation of two of its major historic UK sites, The Giant’s Causeway and the Isle of Staffa, are considered in two papers (respectively, Crawford and Black, this volume; and Gordon, this volume).

Sometimes portrayed as a minor aspect of tourism provision, geotourism is at the casual level one of the most widely practiced forms of natural souvenir collecting; most tourists have at some time collected a pebble or two, even if only when a child at the beach. It is perhaps no surprise then that Gideon Mantell, one of the pre-eminent popularisers of geology in the nineteenth century, drew attention to a refined version of this activity for adults; in his first truly pocketable geology guide to southern England, he wrote that at Rottingdean near Brighton such beach pebbles were “…collected by visitors and when cut and polished are used for bracelets and other ornamental purposes …” (Mantell 1833 , p. 41). He later went on to publish the genesis of the modern illustrated geology field guide (Mantell 1847 ) that was so popular it ran to three editions. It can still be read with profit today and is much sought after. This is a vindication of Mantell’s understanding of what was needed to introduce excursionists, the forerunners of modern geotourists, to geology and how to then fully engage the attention of the reader of a guide book; many modern authors would do well to either learn from or even duplicate his approach! Whilst geotourism has been described as a form of ‘niche’ (Hose 2005 ) or ‘special interest' tourism’ (Jenkins 1992 ), these approaches do not necessarily imply it is restricted to a minority of tourists because they are both actively growing tourism market segments. An early Australian study (Jenkins 1992 ), although employing the term ‘fossicking’, noted that what is now termed geotourism was then a popular activity in Australasia and North America and comprised one of the world’s largest single hobby groups. Tourists in the United States of America (USA) have had a long association with geotourism in the form or ‘rock hounding’ and dinosaur hunting where a mid-1990s study recognised that “Protecting and conserving resources that provide tourism or recreational experiences creates challenges for the development and management of natural heritage areas” (O’Halloran 1996 , p. 495).

Given that study and similar early ones from the USA and Canada, it is then rather odd that National Geographic ignored such domestic, let alone European studies on, geology-focussed geotourism in promoting a more generalist geographical approach. That approach with its emphasis on the natural and human attributes that make a place worth visiting (Tourtellot 2006 ) is just a rebranding of long-standing types of already recognised tourism provision. Its adoption, especially in geoparks and protected landscapes, could actually compromise geoconservation. Geoparks had in much of their geotourist provision already recognised that geology and its associated landscape have a major effect on the economic, social and cultural history of an area. Whilst the majority of geoparks have long embraced the geological approach to geotourism, there has been the recent exception of the organising committee of a geoparks conference, held within a Portuguese geopark noteworthy for the excellence of its geological interpretative provision and geoconservation work, remarkably opting in late 2011 to promote the National Geographic approach. This adoption is despite the acceptance and promotion of the original geology-focussed approach and definition (Hose 1995 ) by UNESCO in its initial geopark documentation (Patzak and Eder 1998 ; UNESCO 2000 ) as a fundamental rationale and underpinning for geoparks worldwide. Geotourism with a particular emphasis on rural localities and geoparks has burgeoned from the opening of the present century. It is perhaps surprising for anyone unfamiliar with geohistory that many of today’s supposed rural areas, such as the Lake District National Park and the Peak District National Park in the UK, have a long mining and quarrying heritage. The previous emphasis particularly in the UK on geotourism associated with such mining and quarrying heritage continues to be a major strand in geotourism; with the often associated retention of industrial buildings and historic transport infrastructure geotourism can be considered a form of ‘heritage tourism’. This emphasis in Europe is reflected in the case study of the Ruhr Geotrail (Wrede and Muegge-Bartolovic, this volume) and various examples from southern Europe (Hose and Vasiljević, this volume).

Geotourism is a developing field of international academic study. The papers in this special issue of Geoheritage are as geographically and topically comprehensive a set, despite those individuals approached because of the quality of their work who were either unable to prepare or eventually submit a finished paper, as it was possible to commission from academic practitioners with an interest in generating a sound theoretical and analytical underpinning. Its papers cover a range of interests from pure definitions of geotourism to a variety of studies related to specific geotourism topics and destinations. Perhaps the two major geographical omissions are papers from the USA and China. In the former, the foundations of the conservation of whole landscapes with spectacular geology were established in the nineteenth century and of environmental and landscape interpretation in the early to mid-twentieth century. In the latter, geoparks have been enthusiastically embraced and significant investment made in their development. However, in the USA, this early emphasis on geology has been lamentably compromised by National Geographic’s approach to geotourism. That some in the European geoparks movement have recently seemingly embraced this diminution of geology in geotourism, without any seeming pan-European geoparks' or geoconservation bodies' agreement on the matter, is to be lamented and rectified; this set of papers should help promote that outcome.

No one volume, whether a set of journal papers or a book, could honestly claim to adequately cover the current breadth of modern geotourism in terms of the nature of provision and geographical coverage, together with its theoretical underpinnings. The papers in this special issue can however justifiably claim to represent much of that breadth through the inclusion of specific case studies and significant overview material. I commend this special issue to you in the hope that it will stimulate further examination, analysis and discussion of geotourism and lead to new researchers becoming engaged in its study and subsequently publishing their work in Geoheritage . The individual authors are to be wholeheartedly thanked for agreeing to prepare their papers and for accepting the rigours of the necessarily lengthy review and revision process that at times must have seemed pedantic. It is hoped they will consider their labours justified and the end result a worthwhile contribution to a better appreciation of geotourism. Putting together this set of papers, at the original invitation of Bill Wimbledon, would not have been possible without the strong editorial support of José Brilha and the attention to detail of the Springer editorial team, but it is to José, for keeping track of the various papers through the lengthy review and revision process, that especial thanks are gladly extended. It is hoped that the geoconservation aspect of this set of geotourism papers is a fitting dedication to the work of the late Gerard Gonggrijp.

Tom Hose (Guest Editor)

Chalton, Bedfordshire, England

Amrikazemi A (2010) Atlas of geopark and geotourism resources of Iran: geoheritage of Iran. Geological Survey of Iran, Tehran

Google Scholar

Barretino D, Wimbledon WP, Gallego E (eds) (2000) Geological heritage: its conservation and management. Instituto Tecnologico Geominero de Espana, Madrid

Dowling RK, Newsome D (eds) (2006) Geotourism. Elsevier, London

Gonggrijp GP, Gonggrijp GP (2000) Planning and management for geoconservation. In: Barretino D, Wimbledon WP, Gallego E, Barretino D, Wimbledon WP, Gallego E (eds) Geological heritage: its conservation and management. Instituto Tecnologico Geominero de Espana, Madrid, pp 29–45

Hose TA (1994) Telling the story of stone—assessing the client base. In: O’Halloran D, Green C, Harley M, Stanley M, Knill J (eds) Geological and landscape conservation. Geological Society, London, pp 451–457

Hose TA (1995) Selling the story of Britain’s stone. Environ Interpretation 10(2):16–17

Hose TA (1996) Geotourism, or can tourists become casual rock hounds? In: Bennett MR (ed) Geology on your doorstep. The Geological Society, London, pp 207–228

Hose TA (1997) Geotourism—selling the Earth to Europe. In: Marinos PG, Koukis GC, Tsiambaos GC, Stournaras GC (eds) Engineering geology and the environment. AA Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 2955–2960

Hose TA (2000) European geotourism—geological interpretation and geoconservation promotion for tourists. In: Barretino D, Wimbledon WP, Gallego E (eds) Geological heritage: its conservation and management. Instituto Tecnologico Geominero de Espana, Madrid, pp 127–146

Hose TA (2003) Geotourism in England: A two-region case study analysis. Birmingham, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham

Hose TA (2005) Geo-tourism—appreciating the deep time of landscapes. In: Novelli M (ed) Niche tourism: contemporary issues, trends and cases. Elsevier, London, pp 27–37

Hose TA (2007) Geoconservation versus geo-exploitation and the emergence of modern geotourism. In: Röhling HG, Breitkreuz ChTh, Duda Th, Stackebrandt W, Witkowski A, Uhlmann O (eds) Abstracts volume, Geo-Pomerania Szczecin 2007 Joint Meeting PTG-DGG: geology cross-bordering the Western and Eastern European platform, 24–26 September 2007. University of Szczecin, Szczecin, p 122

Hose TA (2008) Towards a history of geotourism: definitions, antecedents and the future In: Burek CV and Prosser CD (eds) The History of Geoconservation: Geological Society Special Publication No. 300, Geological Society, London, pp 37–60

Hose TA (2010) Volcanic geotourism in West Coast Scotland. In: Erfurt-Cooper P, Cooper M (eds) Volcano and geothermal tourism: sustainable geo-resources for leisure and recreation. Earthscan, London, pp 259–271

Hose TA (2011) The English origins of geotourism (as a vehicle for geoconservation) and their relevance to current studies. Acta Geographica Slovenica 51–2(2011):343–360

Article Google Scholar

Hose TA, Markovic SB, Komac B, Zorn M (2011) Geotourism—a short introduction. Acta Geographica Slovenica 51–2(2011):339–342

Jenkins JM (1992) Fossickers and rockhounds in Northern New South Wales. In: Weiler B, Hall CM (eds) Special interest tourism. Belhaven Press, London, pp 129–140

Mantell GA (1833) The geology of the south-east of England. Longman, London

Mantell GA (1847) Geological excursion round the Isle of Wight and along the adjacent Coast of Dorsetshire. HG Bohn, London

Newsome D, Dowling RK (eds) (2010) Geotourism: The Tourism of Geology and Landscape. Goodfellow, Oxford

O’Halloran RM (1996) Dinosaurs for tourism: Picket Wire Canyon and the Rocky Mountain palaeontological tourism initiative, Colorado, USA. In: Harrison LC, Husbands W (eds) Practicing responsible tourism: international case studies in tourism planning, policy and development. Wiley, New York, pp 495–508

Patzak M, Eder W (1998) UNESCO Geopark, a new programme—a new UNESCO label. Geologica Balcania 28(3–4):33–35

Robinson E (1998) Tourism in geological landscapes. Geology Today 14(4):151–153

Tourtellot JB (2006) Geotourism for your community: a guide for a geotourism strategy. National Geographic, Washington

UNESCO (2000) UNESCO Geoparks Programme Feasibility Study, August 2000. UNESCO, Paris

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Clifton, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, UK

Thomas Alfred Hose

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Thomas Alfred Hose .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hose, T.A. Editorial: Geotourism and Geoconservation. Geoheritage 4 , 1–5 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-012-0059-z

Download citation

Received : 04 February 2012

Accepted : 15 February 2012

Published : 06 March 2012

Issue Date : April 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-012-0059-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Turn Your Curiosity Into Discovery

Latest facts.

12 Facts About Beer Pong Day May 4th

15 Facts About National Gummi Bear Day April 27th

40 facts about elektrostal.

Written by Lanette Mayes

Modified & Updated: 02 Mar 2024

Reviewed by Jessica Corbett

Elektrostal is a vibrant city located in the Moscow Oblast region of Russia. With a rich history, stunning architecture, and a thriving community, Elektrostal is a city that has much to offer. Whether you are a history buff, nature enthusiast, or simply curious about different cultures, Elektrostal is sure to captivate you.

This article will provide you with 40 fascinating facts about Elektrostal, giving you a better understanding of why this city is worth exploring. From its origins as an industrial hub to its modern-day charm, we will delve into the various aspects that make Elektrostal a unique and must-visit destination.

So, join us as we uncover the hidden treasures of Elektrostal and discover what makes this city a true gem in the heart of Russia.

Key Takeaways:

- Elektrostal, known as the “Motor City of Russia,” is a vibrant and growing city with a rich industrial history, offering diverse cultural experiences and a strong commitment to environmental sustainability.

- With its convenient location near Moscow, Elektrostal provides a picturesque landscape, vibrant nightlife, and a range of recreational activities, making it an ideal destination for residents and visitors alike.

Known as the “Motor City of Russia.”

Elektrostal, a city located in the Moscow Oblast region of Russia, earned the nickname “Motor City” due to its significant involvement in the automotive industry.

Home to the Elektrostal Metallurgical Plant.

Elektrostal is renowned for its metallurgical plant, which has been producing high-quality steel and alloys since its establishment in 1916.

Boasts a rich industrial heritage.

Elektrostal has a long history of industrial development, contributing to the growth and progress of the region.

Founded in 1916.

The city of Elektrostal was founded in 1916 as a result of the construction of the Elektrostal Metallurgical Plant.

Located approximately 50 kilometers east of Moscow.

Elektrostal is situated in close proximity to the Russian capital, making it easily accessible for both residents and visitors.

Known for its vibrant cultural scene.

Elektrostal is home to several cultural institutions, including museums, theaters, and art galleries that showcase the city’s rich artistic heritage.

A popular destination for nature lovers.

Surrounded by picturesque landscapes and forests, Elektrostal offers ample opportunities for outdoor activities such as hiking, camping, and birdwatching.

Hosts the annual Elektrostal City Day celebrations.

Every year, Elektrostal organizes festive events and activities to celebrate its founding, bringing together residents and visitors in a spirit of unity and joy.

Has a population of approximately 160,000 people.

Elektrostal is home to a diverse and vibrant community of around 160,000 residents, contributing to its dynamic atmosphere.

Boasts excellent education facilities.

The city is known for its well-established educational institutions, providing quality education to students of all ages.

A center for scientific research and innovation.

Elektrostal serves as an important hub for scientific research, particularly in the fields of metallurgy, materials science, and engineering.

Surrounded by picturesque lakes.

The city is blessed with numerous beautiful lakes, offering scenic views and recreational opportunities for locals and visitors alike.

Well-connected transportation system.

Elektrostal benefits from an efficient transportation network, including highways, railways, and public transportation options, ensuring convenient travel within and beyond the city.

Famous for its traditional Russian cuisine.

Food enthusiasts can indulge in authentic Russian dishes at numerous restaurants and cafes scattered throughout Elektrostal.

Home to notable architectural landmarks.

Elektrostal boasts impressive architecture, including the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord and the Elektrostal Palace of Culture.

Offers a wide range of recreational facilities.

Residents and visitors can enjoy various recreational activities, such as sports complexes, swimming pools, and fitness centers, enhancing the overall quality of life.

Provides a high standard of healthcare.

Elektrostal is equipped with modern medical facilities, ensuring residents have access to quality healthcare services.

Home to the Elektrostal History Museum.

The Elektrostal History Museum showcases the city’s fascinating past through exhibitions and displays.

A hub for sports enthusiasts.

Elektrostal is passionate about sports, with numerous stadiums, arenas, and sports clubs offering opportunities for athletes and spectators.

Celebrates diverse cultural festivals.

Throughout the year, Elektrostal hosts a variety of cultural festivals, celebrating different ethnicities, traditions, and art forms.

Electric power played a significant role in its early development.

Elektrostal owes its name and initial growth to the establishment of electric power stations and the utilization of electricity in the industrial sector.

Boasts a thriving economy.

The city’s strong industrial base, coupled with its strategic location near Moscow, has contributed to Elektrostal’s prosperous economic status.

Houses the Elektrostal Drama Theater.

The Elektrostal Drama Theater is a cultural centerpiece, attracting theater enthusiasts from far and wide.

Popular destination for winter sports.

Elektrostal’s proximity to ski resorts and winter sport facilities makes it a favorite destination for skiing, snowboarding, and other winter activities.

Promotes environmental sustainability.

Elektrostal prioritizes environmental protection and sustainability, implementing initiatives to reduce pollution and preserve natural resources.

Home to renowned educational institutions.

Elektrostal is known for its prestigious schools and universities, offering a wide range of academic programs to students.

Committed to cultural preservation.

The city values its cultural heritage and takes active steps to preserve and promote traditional customs, crafts, and arts.

Hosts an annual International Film Festival.

The Elektrostal International Film Festival attracts filmmakers and cinema enthusiasts from around the world, showcasing a diverse range of films.

Encourages entrepreneurship and innovation.

Elektrostal supports aspiring entrepreneurs and fosters a culture of innovation, providing opportunities for startups and business development.

Offers a range of housing options.

Elektrostal provides diverse housing options, including apartments, houses, and residential complexes, catering to different lifestyles and budgets.

Home to notable sports teams.

Elektrostal is proud of its sports legacy, with several successful sports teams competing at regional and national levels.

Boasts a vibrant nightlife scene.

Residents and visitors can enjoy a lively nightlife in Elektrostal, with numerous bars, clubs, and entertainment venues.

Promotes cultural exchange and international relations.

Elektrostal actively engages in international partnerships, cultural exchanges, and diplomatic collaborations to foster global connections.

Surrounded by beautiful nature reserves.

Nearby nature reserves, such as the Barybino Forest and Luchinskoye Lake, offer opportunities for nature enthusiasts to explore and appreciate the region’s biodiversity.

Commemorates historical events.

The city pays tribute to significant historical events through memorials, monuments, and exhibitions, ensuring the preservation of collective memory.

Promotes sports and youth development.

Elektrostal invests in sports infrastructure and programs to encourage youth participation, health, and physical fitness.

Hosts annual cultural and artistic festivals.

Throughout the year, Elektrostal celebrates its cultural diversity through festivals dedicated to music, dance, art, and theater.

Provides a picturesque landscape for photography enthusiasts.

The city’s scenic beauty, architectural landmarks, and natural surroundings make it a paradise for photographers.

Connects to Moscow via a direct train line.

The convenient train connection between Elektrostal and Moscow makes commuting between the two cities effortless.

A city with a bright future.

Elektrostal continues to grow and develop, aiming to become a model city in terms of infrastructure, sustainability, and quality of life for its residents.

In conclusion, Elektrostal is a fascinating city with a rich history and a vibrant present. From its origins as a center of steel production to its modern-day status as a hub for education and industry, Elektrostal has plenty to offer both residents and visitors. With its beautiful parks, cultural attractions, and proximity to Moscow, there is no shortage of things to see and do in this dynamic city. Whether you’re interested in exploring its historical landmarks, enjoying outdoor activities, or immersing yourself in the local culture, Elektrostal has something for everyone. So, next time you find yourself in the Moscow region, don’t miss the opportunity to discover the hidden gems of Elektrostal.

Q: What is the population of Elektrostal?

A: As of the latest data, the population of Elektrostal is approximately XXXX.

Q: How far is Elektrostal from Moscow?

A: Elektrostal is located approximately XX kilometers away from Moscow.

Q: Are there any famous landmarks in Elektrostal?

A: Yes, Elektrostal is home to several notable landmarks, including XXXX and XXXX.

Q: What industries are prominent in Elektrostal?

A: Elektrostal is known for its steel production industry and is also a center for engineering and manufacturing.

Q: Are there any universities or educational institutions in Elektrostal?

A: Yes, Elektrostal is home to XXXX University and several other educational institutions.

Q: What are some popular outdoor activities in Elektrostal?

A: Elektrostal offers several outdoor activities, such as hiking, cycling, and picnicking in its beautiful parks.

Q: Is Elektrostal well-connected in terms of transportation?

A: Yes, Elektrostal has good transportation links, including trains and buses, making it easily accessible from nearby cities.

Q: Are there any annual events or festivals in Elektrostal?

A: Yes, Elektrostal hosts various events and festivals throughout the year, including XXXX and XXXX.

Was this page helpful?

Our commitment to delivering trustworthy and engaging content is at the heart of what we do. Each fact on our site is contributed by real users like you, bringing a wealth of diverse insights and information. To ensure the highest standards of accuracy and reliability, our dedicated editors meticulously review each submission. This process guarantees that the facts we share are not only fascinating but also credible. Trust in our commitment to quality and authenticity as you explore and learn with us.

Share this Fact:

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

GeoWorld Travel specialises in geology trips, tours and holidays. Our geotourism tours are small group, special interest tours and visit fossil and volcano sites and the scenery is explained. GeoWorld Travel offers trips in Antarctica, the Arctic, England, Canary Islands, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Morocco, Namibia, Oman, Scotland, USA and Wales.

Geological sustainable tourism aims to conserve and promote a place as a geosite, such as the Iguazu Falls in South America. Geotourism is tourism associated with geological attractions and destinations. Geotourism (tourism with a geological base) deals with the abiotic natural and built environments. Geotourism was first defined in England by Thomas Alfred Hose in 1995.

Geotourism is defined as tourism that sustains or enhances the distinctive geographical character of a place—its environment, heritage, aesthetics, culture, and the well-being of its residents.

The best place to see the remnants of an impact is Meteor Crater, east of Flagstaff, a privately owned tourist attraction. The crater is 4,000 feet wide, almost 600 feet deep and will put the fear ...

Tourism Geology. Tourism geology is an interdisciplinary subject of geology and tourism that studies geology-related issues in tourism, including the classification, formation, evolution and implications of geological features and processes, their regional distribution, and the processes and aesthetic features of geology and landforms in nature ...

Geotourism is an approach to tourism which starts with geology as a basis for understanding the environment. It comprises the ABC elements of the environment, that is, the Abiotic (non-living) elements of earth and climate, as these have shaped the Biotic (living) elements of plants and animals, which in turn have shaped the Cultural elements, both past (indigenous) and present (current ...

Geotourism is essentially 'geological tourism'. The geological element focuses on geology and landscape and includes both 'form', such as landforms, rock outcrops, rock types, sediments, soils and crystals, and 'process', such as volcanism, erosion, glaciation etc. The tourism element of geotourism includes tourists visiting, learning from, appreciating and engaging in geosites ...

Tourism and Hospitality is an international peer-reviewed open access quarterly journal published by MDPI. Please visit the Instructions for Authors page before submitting a manuscript. The Article Processing Charge (APC) for publication in this open access journal is 1200 CHF (Swiss Francs). Submitted papers should be well formatted and use ...

Geotourism: the tourism of geology and landscape is a compilation of first class international research which provides insight into the many facets of this emerging subject, and comprehensively explores the nexus between landscape, geological phenomena and tourism. Covering information on landscape appreciation, geoheritage, management, interpretation, education and the future of geotourism ...

Geotourism is tourism based on geological features. Over time it has been variously described as being a type of tourism that is either 'geological' or geographical' in orientation. Whereas the former view was that geotourism was a 'type' of tourism in a similar vein to ecotourism, the latter view was wider and encompassed it thereby ...

In the tourism context being explored here, however, geology is the centrepiece and the geological focus is where geotourism clearly differs from other forms of tourism. The emphasis on geology requires specialist knowledge in (1) presenting a site for public access and managing potential negative impacts, (2) managing the site in terms of geo ...

Geotourism is one of the newest concepts within tourism studies today. The popularity of geotourism has likewise grown rapidly over the past few decades. This rapidly growing popularity and the growing body of research on geotourism create the need for a comprehensive review of existing literature on the subject. The present study aims to systematically review scientific literature on ...

Geotourism is a sub-niche of nature tourism characterized by being environmentally innovative and focusing specifically on landscape and geology . According to Dowling and Newsome [ 2 ] , geotourism has expanded to encompass several attributes—geology, tourism, geosites, visits, and interpretation—and needs to be considered not as a type of ...

1. Introduction. During the past two decades, geological tourism (geotourism) has become an important activity on the local, national, and international levels (Dowling, 2011, Dowling and Newsome, 2010, Farsani et al., 2014, Gray, 2013, Lazzari and Aloia, 2014).It employs geological heritage sites (geosites), ex situ heritage objects (primarily those from museum collections), specially created ...

Geotourism focuses on an area's geology and landscape as the basis of fostering sustainable tourism development. Its first published definition is about the provision of interpretive and service facilities to enable tourists to acquire knowledge and understanding of the geology and geomorphology of a site (including its contribution to the development of the Earth sciences) beyond the level ...

Geotourism is tourism based on geological features. It has been variously described as being a type of tourism that is either 'geological' or geographical' in orientation. Whereas the former view was that geotourism was a 'type' of tourism in a similar vein to ecotourism, the latter view was wider and encompassed it thereby representing a new 'approach' to tourism.

National Geographic defines geotourism as tourism that sustains or enhances the geographical character of a place - its environment, geology, culture, aesthetics, heritage and the well-being of its resident. Academic institutions, tourism bureaus, the hospitality industry, regional and national governments have begun to adopt this new concept ...

Geology and minerals Geology Dolomite Gneiss. Moscow Oblast is located in the central part of the East European craton. Like all cratons, the latter is composed of the crystalline basement and sedimentary cover. The basement consists of Archaean and Proterozoic rocks and the cover is deposited in the Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras.

Moscow metro to be more tourist-friendly. Aug 11 2014 Yelena Dolzhenko specially for RIR A new floor sign system at the Moscow metro's Pushkinskaya station. ...

Geotourism is a term that appeared, firstly, in the 1990s defined by Hose as a tourism niche product "geological based" and secondly, on 2002, by the National Geographic Society as a tourism and territorial approach "geographical based."Geotourism can be, currently, defined according to Dowling and Newsome (), as a form of tourism which focuses on an area's geology and landscape, as ...

In 1938, it was granted town status. [citation needed]Administrative and municipal status. Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is incorporated as Elektrostal City Under Oblast Jurisdiction—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts. As a municipal division, Elektrostal City Under Oblast Jurisdiction is incorporated as Elektrostal Urban Okrug.

Geotourism has had a key role over the last decade or so in such promotional work and has undoubtedly made a major contribution to bringing geology to the attention of a greater number of the populace than was thitherto achieved. Geotourism is a relatively newly recognised but rapidly developing form of geology-based tourism.

40 Facts About Elektrostal. Elektrostal is a vibrant city located in the Moscow Oblast region of Russia. With a rich history, stunning architecture, and a thriving community, Elektrostal is a city that has much to offer. Whether you are a history buff, nature enthusiast, or simply curious about different cultures, Elektrostal is sure to ...