What is inbound tourism explained and why does it matter?

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Inbound tourism is an important type of tourism . Many countries rely heavily on the demand from inbound tourists to fuel the development and operations of their tourism economy.

But what does it actually mean to be an inbound tourist? In this article I will explain what is meant by the term inbound tourism, provide definitions of inbound tourism and I will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of inbound tourism. Lastly, I will provide examples of destinations which have significantly sized inbound tourism markets.

What is inbound tourism?

Inbound tourism definitions, the importance of inbound tourism, uk inbound tourism, advantages of inbound tourism, disadvantages of inbound tourism, inbound tourism: conclusion, further reading on inbound tourism.

Inbound tourism is the act of someone travelling to a country other than that of where they live for the purpose of tourism.

Many countries around the world rely on inbound tourism.

Inbound tourism is often seasonal, meaning that many destinations will have evident peak, shoulder and low seasons. This is often dependant on weather conditions (for example sun or snow ) and school and public holidays.

The most widely utilised definition of tourism , proposed by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and United States (UN) Nations Statistics Division (1994), prescribes that in order to qualify as a tourist one must travel and remain in a place outside of their usual residential environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business or other purposes.

When considering inbound tourism, it therefore makes sense to simply add in the prerequisite of travelling to another country…

Based on this commonly accepted definition (although this is not without its limits- see this post for more details ), therefore, inbound tourism can be defined as:

‘The act of travelling to another country for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business or other purposes.’

Inbound tourism is incredibly important in many destinations.

This is largely because of the economic benefits of tourism . Tourism can bring in a lot of money to a country through foreign exchange. This is particularly beneficial in countries where the currency is weaker than the currency of the tourists ‘ home countries.

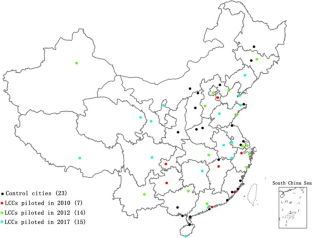

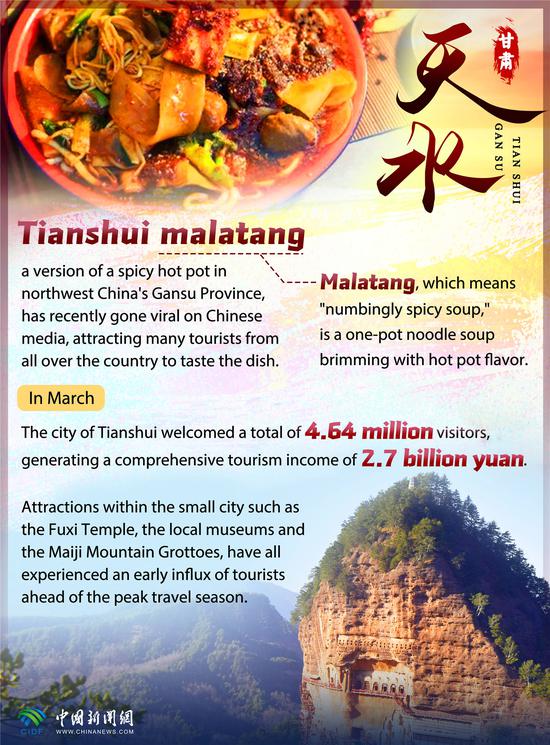

It is for this reason that many countries will target their advertising towards certain nationalities. China produces one of the largest outbound tourism markets in the world and Chinese tourists tend to spend more on their holidays than any other nationality. Therefore many countries want to attract Chinese inbound tourists due to the economic value of this market.

Click here to see some interesting statistics demonstrating the growth in the Chinese outbound tourism market.

However, over dependance on inbound tourism can be risky business for destinations. There are many destinations, such as the Maldives , Spain and Greece who rely heavily on people travelling from other countries to their country for tourism.

The problem occurs when the travel industry is disrupted. This has never been more true than during the 2020 pandemic, when the impacts of Coronavirus on tourism were devastating.

Inbound tourism can also be negatively effected as a result of other factors, such as political unrest, natural disasters or economic instability.

In order to ensure sustainable tourism principles are adopted, destinations ideally need to diversify their tourism product to appeal to both the domestic tourism market and the inbound tourism market.

In The United Kingdom, we have a sizeable inbound tourism industry.

Here, inbound tourism is worth £127 billion per year to the UK economy. Inbound tourism creates jobs and boosts the economic throughout the country.

According to the UK tourist board, Visit Britain , inbound visitors to the UK spent £24.5 billion in 2017, and £21 billion of that was spent in England.

Inbound tourism attracts tourists from all over the world including Europe, the USA, Australia , China and Japan.

Inbound tourism markets around the world

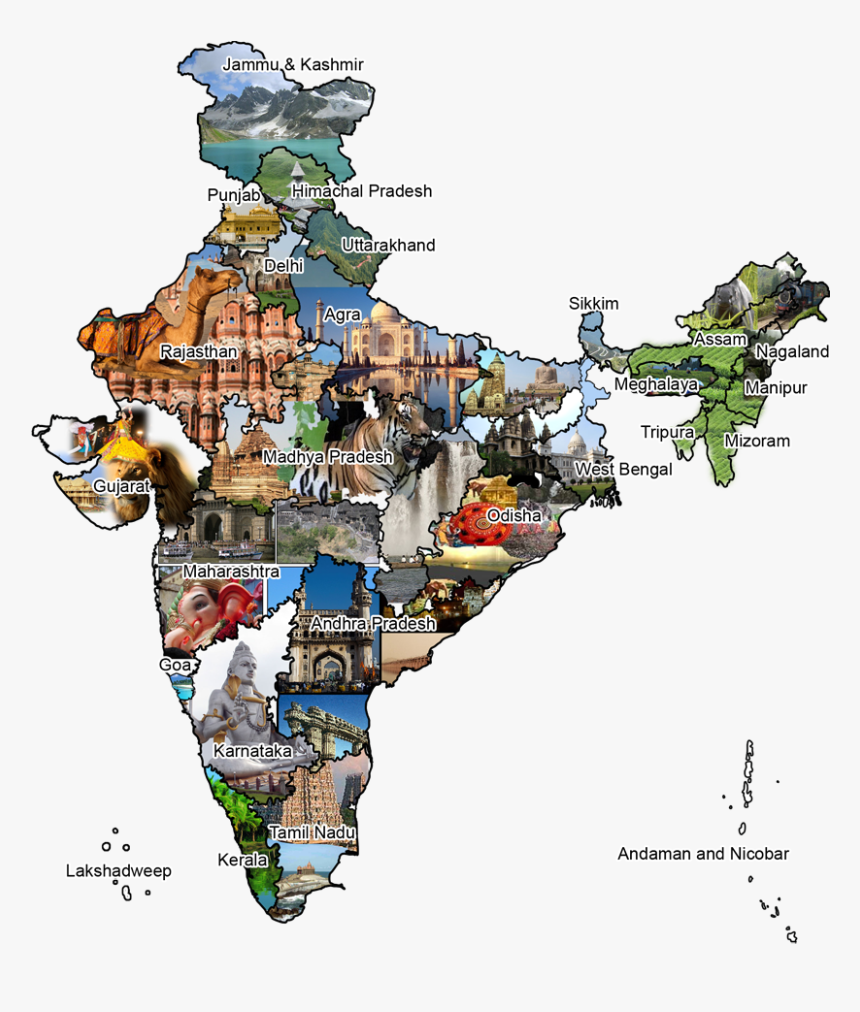

Inbound tourism is a significant part of the tourism industry in many countries around the world.

The OECD have some useful data, demonstrating the most recent figures for inbound tourism around the world.

To take a look at the most recent OECD inbound tourism figures click here.

Here are a few tourism markets that have a high number of inbound tourists each year-

According to Statistica , Spain ranked second on the World Tourism Organisation’s list of most visited countries in the world, with its number of international visitors amounting to nearly 89.4 million in 2018.

Most travellers to Spain come from Europe, with the largest amount of tourists being British.

Spain is popular for its beach holidays, package holiday market and city breaks to Barcelona, Madrid and Valencia, amongst others.

The Maldives has been host to a fast-growing tourism industry in recent years. The archipelago attracts visitors all-year round, especially in hubs like Male which is home to an increasing number of modern hotels.

Statistica reported in February 2019 that there were sharp increases in economic activity in The Maldives resulting from tourism. Figures showed a 16.8% increase in inbound tourism from the same time the previous year.

In total, 168,583 inbound tourists were recorded in The Maldives in 2019. China accounted for 17.8% and European markets accounted for a further 55% of inbound tourism.

The Maldives is renowned for its luxurious beach holidays.

Inbound tourism is one of the biggest economic activities in Thailand .

The National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) stated that in February 2019 the tourism industry accounted for 18.4% of GDP. Chinese visitors make up almost one third of all inbound tourists travelling to Thailand , with 10.99 million visits recorded in 2019.

There are many types of tourism found in Thailand and Thailand attracts a range of types of tourists, from backpackers to luxury travellers to business tourists .

Bali is another destination that is reliant on inbound tourism as a key economic contributor.

In 2018, the number of foreign tourists travelling to Bali was over 5 million. This was an increase of approximately 3.5 million from 2008. Figures taken from Statistica .

The inbound tourism market in Bali is dominated largely by Chinese and Australian tourists.

Bali is well-known for its beach escapes and cultural tourism .

There are many advantages of inbound tourism.

One advantage is that inbound tourism is not reliant on weekends in the way that domestic tourism is because people tend to your their annual leave when they take holidays overseas.

Having an inbound tourism market that attracts tourists from a range of destinations can help to minimise risk and diversify income. This way, if for some reason one country does not send many tourists (for example due to political or economic problems) then the host country still has visitors arriving from other countries.

On average, inbound tourists spend more money than domestic tourists. This money then helps boost the economy of the host country.

When we travel overseas we typically book further in advance than if we booked a domestic trip. This allows tourism organisations more time to plan.

Foreign income can really help to boost the economy of a country. Therefore foreign tourists are often welcomed. This especially applies to tourists who come from destinations where the currency is strong (e.g. Britain, USA, Europe, Australia).

Other posts that you might be interested in: – What is tourism? A definition of tourism – The history of tourism – The structure of the tourism industry – Stakeholders in tourism – Dark tourism explained – What is ABTA and how does it work? – The economic impacts of tourism

There are also some disadvantages of inbound tourism.

The main disadvantage of inbound tourism is that the destination is at the mercy of the transport network.

There are many cases of tourism industries being decimated because an airline has stopped operating a particular route.

Inbound tourism can also lead to culture clashes.

For example, British tourists who travel to Dubai are often not aware of Muslim cultural practices. As such, it is common for the local population to be offended by the tourist’s behaviour. In Dubai there are many signs up in the malls, for instance, that requests tourists cover up and dress appropriately .

In conclusion, it can be seen that inbound tourism is a highly effective way for a country to make money from tourism. Whilst this does take some careful management and planning, there are many countries throughout the world who have successful and thriving inbound tourism industries.

- An Introduction to Tourism : a comprehensive and authoritative introduction to all facets of tourism including: the history of tourism; factors influencing the tourism industry; tourism in developing countries; sustainable tourism; forecasting future trends.

- The Business of Tourism Management : an introduction to key aspects of tourism, and to the practice of managing a tourism business.

- Tourism Management: An Introduction : gives its reader a strong understanding of the dimensions of tourism, the industries of which it is comprised, the issues that affect its success, and the management of its impact on destination economies, environments and communities.

Liked this article? Click to share!

This platform and its APIs have reached their end of life and will be switched-off at the end of May 2024.

Data are not updated anymore. We invite you to use instead our new data dissemination platform OECD Data Explorer.

To find the corresponding OECD Data Explorer dataset, see this Excel file.

- Data by theme

- Popular queries

- Business Demography

- Birth rate of enterprises

- Death rate of enterprises

- Enterprise survival rates

- Employment creation and destruction

- High-Growth enterprises rate (employment definition)

- High-Growth enterprises rate (turnover definition)

- Business Demography Indicators ISIC4

- High-Growth enterprises

- Medium and High-Growth enterprises

- Number of active enterprises

- Share of employer start-ups

- Structural Business Statistics

- All Businesses (SSIS)

- Mining and quarrying (By Size Class)

- Manufacturing (By Size Class)

- Electricity, gas & water (By Size Class)

- Construction (By Size Class)

- Wholesale and retail trade (By Size Class)

- Hotels & restaurants (By Size Class)

- Transport, storage & communications (By Size Class)

- Real estate, renting and business activities (By Size Class)

- Structural Business Statistics - ISIC4

- Employment of SMEs and large firms

- Number of SMEs and large firms

- Production by sector (Total size)

- Productivity of SMEs and large firms

- Total number of enterprises, by sector

- Turnover of SMEs and large firms

- Value added of SMEs and large firms

- I: TEC by Size classes

- II: TEC by Top enterprises

- III: TEC by Partner zones and countries

- IV: TEC by number of partner countries

- V: TEC by commodity groups (CPC)

- I - TEC by sector and size class

- III - TEC by partner zones and countries

- IV - TEC by number of partner countries

- IX - TEC by activity sectors

- V - TEC by commodity groups (CPC)

- VI - TEC by type of trader

- VII - TEC by ownership

- VIII - TEC by exports intensity

- X - TEC by partner countries and size-class

- Employer enterprise demography, Large TL2 and small TL3 regions

- Enterprise Demography (all firms, incl. non employer)

- Establishment Regional Demography

- Indicators of female entrepreneurship

- Timely Indicators of Entrepreneurship (ISIC4)

- New enterprise creations

- Bankruptcies of enterprises

- Exits of enterprises

- Timely Indicators of Entrepreneurship by Enterprise Characteristics

- Number of enterprise entries

- Number of enterprise exits

- Number of enterprise bankruptcies

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Venture capital investments

- Future of Business Survey

- Businesses by sector

- Businesses by size

- Businesses by age

- Businesses by sex, single owner

- Businesses by sex, multiple ownership

- Businesses and international trading

- Share of exporters by export scope

- Sources of business funding

- Outlook on business

- Outlook on job creation

- Positive business status and outlook, by sex

- Production and Sales (MEI)

- Work started

- STAN: Database for Structural Analysis (ISIC4 SNA08)

- iSTAN: Indicators for structural analysis

- BTDIxE: Bilateral Trade by Industry and End-use

- TiM 2021: Trade in employment

- TiM 2023: Trade in employment

- TiM 2021: Trade in employment by characteristics

- IOTs 2021: Input-Output Tables

- IOTs 2018: Input-Output Tables

- IOTs 2015: Input-Output Tables

- TeCO2: CO2 emissions embodied in trade

- TeCO2: Principal indicators

- Embodied CO2 emissions in trade

- Embodied CO2 emissions in trade: Principal indicators

- TiM 2019: Trade in employment

- ANBERD (R&D by industry)

- 1. TiVA 2018: Principal indicators

- 2. TiVA 2018: Origin of value added in gross exports

- 3. TiVA 2018: Origin of value added in final demand

- 4. TiVA 2018: Gross exports by origin of value added and final destination

- 5. TiVA 2018: Origin of value added in gross imports

- 1. TiVA 2016: Main indicators

- 2. TiVA 2016: Origin of value added in gross exports

- 3. TiVA 2016: Origin of value added in final demand

- 4. TiVA 2016: Gross exports by final destination

- 5. TiVA 2016: Origin of value added in gross imports

- TiVA, October 2015

- Trade in Value Added (TiVA): Core Indicators

- TiVA 2015: Origin of Value Added in Gross Exports

- TiVA 2015: Origin of Value Added in Final Demand

- TeCO2 2015: CO2 emissions embodied in trade

- OECD Global Value Chains indicators – May 2013

- Indices of the number of production stages

- Participation indices

- TiVA Nowcast Estimates

- TiM 2015: Core Indicators

- BTDIxE 2016

- BTDIxE 2011

- BTDIxE 2012

- TeCO2 2013: CO2 emissions embodied in trade

- STAN 2016: Database for Structural Analysis

- STAN 2011: Database for Structural Analysis (ISIC Rev.3 SNA93)

- STAN 2012: Database for Structural Analysis (ISIC Rev.4 SNA93)

- STAN 2005: Database for Structural Analysis

- STAN Indicators 2012

- STAN Indicators 2011 (ISIC3 SNA93)

- Manufacturing share of employment 1970-2009

- Manufacturing share of value-added 1970-2009

- R&D intensity of manufacturing sectors 1995-2009

- STAN Indicators 2009

- STAN Indicators 2005

- STAN I-O Intermediate Import Ratio, March 2012

- STAN Input-Output Total, Domestic and Imports, March 2012

- STAN I-O Imports content of Exports, March 2012

- STAN I-O Inverse Matrix Coefficients (Domestic), March 2012

- STAN I-O Inverse Matrix (Total), March 2012

- ANBERD: business enterprise R&D by industry (ISIC Rev. 3)

- ANBERD: business enterprise R&D by industry (ISIC Rev. 2)

- Services Trade Restrictiveness Index by services sector

- STRI Heterogeneity Indices

- Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index

- Digital STRI Heterogeneity Indices

- Intra-EEA Services Trade Restrictiveness Index

- Intra-EEA STRI Heterogeneity Indices

- Steelmaking Capacity

- Receipts and expenditure

- Domestic tourism

Inbound tourism

- Outbound tourism

- Enterprises and employment in tourism

- Internal tourism consumption

- Key tourism indicators

- TiVA 2021: Principal Indicators

- Economic Outlook

- Gross domestic product (annual)

- Gross domestic product (quarterly)

- Composite Leading Indicators

- Consumer price indices - inflation

- Health Status

- Labour Market Statistics

- Monthly Monetary and Financial Statistics (MEI)

- Agricultural Outlook

- Bilateral Trade by Industry and End-use (ISIC4)

- Statistics from A to Z

This dataset preview is momentarily unavailable.

Please try again or select another dataset.

- Country [61 / 61]

- Variable [92 / 92]

- Source [2 / 2]

- Year [14]

- Table options

- Text file (CSV)

- Developer API

- Related files

Information

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Economic impacts of COVID-19 on inbound and domestic tourism ☆

COVID-19 has led to an unprecedented disruption in tourism spending. This has propagated through the whole economy, however the scale of these system-wide consequences can be hard to quantify. We calculate direct reductions in spending across domestic and inbound tourism categories and then use a computable general equilibrium model to quantify their economic impacts. The results – illustrated using a model for Scotland and focusing on 2021 - demonstrate the scale of the losses in the tourism industry and the economy as a whole that are attributable to changes in both domestic and inbound tourism demand. We find that the extent to which domestic tourism demand can mitigate the losses in inbound spending depends on the composition of demand.

1. Introduction

Since the start of 2020, the world has been impacted by the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), which has led to over 603 million cumulative cases and 6.48 million deaths ( World Health Organisation, 2022 , as of 8th September 2022 ). Across the globe, there has been an unprecedented national-level policy response to limit the spread of the virus, including restrictions on movement (both inter- and intra-national) and social and business activities where virus transmission could occur, a move to home working, local-, regional- and national-lockdowns, and restrictions on schooling and other normally “in-person” activities.

One of the most immediate consequences of the policy interventions was the “stop” to global tourism, with restrictions on international travel, stay at home orders and a curtailment of tourism activity. As the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (2020) noted in April 2020, “100% of destinations now have restrictions in place”. Niewiadomski (2020, p. 3) puts it more succinctly: “As a result, tourism as we knew it just a few months ago has ceased to exist.” Changes in the ability to undertake tourism activities are likely to have major economic impacts, particularly on regions and nations where tourism supported a substantial amount of economic activity.

While tourism in general was greatly affected by the measures aimed at reducing the spread of the virus, for many regions, domestic travel has seen a faster phased return compared to international tourism in both 2021 and 2022 since local mobility was less restricted than international mobility. Thus, increasing domestic tourism in place of lost international tourism has been identified as a potential strategy to mitigate the negative impacts of reduced tourism demand ( Arbulú, Razumova, Rey-Maquieira, & Sastre, 2021 ). However, recent studies - that have focussed primarily on the impact that COVID-19 had on the hotel industries - find mixed support for the thesis that policies aimed at attracting local tourists can be effective mitigating tools especially at the local level. For instance, Duro, Perez-Laborda, & Fernandez (2022) , finds that domestic tourism had a limited role in explaining the resilience of the accommodation sector in Spanish regions. This result is corroborated by the findings in Boto-García & Mayor (2022) that on average only regions with higher pre-pandemic domestic tourism demand were more attractive to domestic tourists thus had a greater ability to resist the negative demand shock from the loss of international tourists.

These studies have focussed on the regional impact of reduced tourism demand in the accommodation sector only. However, the economic impacts from reduced tourism spending will not only be limited to accommodation or to tourist-facing activities, such as restaurants and museums. The impacts will also be felt in other sectors of the economy such as those which are connected to tourism through supply chain links, or those affected by the corresponding reduction in incomes from a contraction in tourism activity. For this reason, some studies use multi-sectoral macroeconomic models, such as computable general equilibrium, which are particularly useful in understanding the propagation of changes in tourism behaviour and expenditure to the economy as a whole (see Dwyer, Forsyth, Madden, & Spurr, 2000 ; Dwyer, Forsyth, & Spurr, 2004 ; Wickramasinghe & Naranpanawa, 2021 for some general review of the usefulness of such models).

Of the growing literature to date that use computable general equilibrium modelling to analyse the economy-wide impact of COVID-related changes in tourism, two key papers are Pham, Dwyer, Su, and Ngo (2021) and Henseler, Maisonnave, and Maskaeva (2022) . Both these papers are mostly concerned with changes in inbound arrivals (i.e., trips and spending associated with non-residents of those areas). Whilst this is perfectly sensible for places that rely primarily on inbound travel for tourism demand, domestic tourism demand (i.e., trips and spending by residents) may play a major role for tourism recovery of regions with a strong domestic-facing tourism economy. This is particularly important as travel intentions, and attitudes to attitudes to risk and uncertainty about international travel have been made more complex in the COVID-19 crises ( Williams, Chen, Li, & Baláž, 2022 ).

In this paper, we use a computable general equilibrium model of Scotland to understand the impact that changes in domestic and inbound tourism spending in 2021, the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, have had on the Scottish economy. That is, we do not seek to estimate the overall economic impact of the pandemic on the Scottish economy, but we propose a methodology to capture the impact of variations in domestic and inbound tourism spending. Scotland makes an interesting empirical case for analysing tourism, given the importance of the sector for the economy, and the central place for tourism in its economic strategy ( Scottish Government, 2015 ; Scottish Government, 2021a ). Our focus on 2021 is to better understand the links between the evolution of COVID-19 policies in this period, which begins with the second national lockdown and evolves with changes in case numbers and the roll-out of the vaccine programme. Whilst our focus is on Scotland, we believe that the main lessons learned for this economy can be transferred to any region where domestic tourism demand is an important element of the tourism industry and can be used to further extend the micro literature on domestic tourism demand (Duro et al., 2022; Boto-García & Mayor, 2022 ) by exploring the role of composition of demand by tourism categories and by adding a macroeconomic dimension. In addition, the method used here is directly applicable to other regions where the data is available.

We make two main contributions in this paper. First, we develop a method that can be used for the short-run economic analysis of variations in both domestic and inbound tourism spending. This method can be replicated for other regions and countries provided the existence of spending data by each tourism category. Second, we contribute to the growing literature on whether additional domestic tourism demand can mitigate the loss in inbound spending at the macroeconomic level due to COVID-19. Specifically, we add to the existing literature by a) focussing on a set of aggregated industries, that are both tourism facing or linked to tourism via supply chain, b) explaining the role of the composition of demand of domestic and international tourism spending in determining resistance of local economies to unpredicted economic shocks (e.g., Allan, Lecca, & Swales, 2017 ).

We try to overcome some of the weaknesses of computable general equilibrium modelling. Typically, computable general equilibrium models are limited in the ability to represent the geographic and temporal origin of shocks as they rely on annual country-level data. However, many countries' COVID policies in 2021 have seen tourism demand vary significantly by regions - in accordance with infection rates and the evolution of the pandemic - and by month, following the rollout of vaccination programmes. For this reason, we first carry out a bottom-up analysis of tourism expenditure in Scotland disaggregated by place of residence of tourists, namely Scotland (including a distinction between day visits and overnight stays), the rest of the UK (day trips and overnight) and international, and by destination of spending at local authority level for each of the 2021 months. This lets us identify the different contribution of five categories of tourism expenditure in Scotland pre-COVID-19, which can then be “shocked” by observed changes in relevant proxies during 2021. Crucially, when restrictions are applied to sub-regional areas of the country, we are able to capture shocks that are proportionate to the spending profile of different tourism categories in that region. Second, by introducing proxies for each category's movement during 2021, we identify changes in tourism expenditure attributable to COVID-19, by local authority and month, which are then aggregated and introduced as disturbances to a computable general equilibrium model for Scotland, to show how these propagate through the Scottish economy to produce impacts on aggregate economic indicators and on different sectors.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 sets out an overview of the tourism industry in Scotland and the economic contribution of different categories of tourism expenditure and presents a timeline of the key phases of the COVID-19 pandemic and policies in Scotland, focusing on 2021. Section 3 summarises recent papers which have used computable general equilibrium analysis to understand the wider impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly through the policies targeted at travel and the tourism industry. Section 4 sets out our methodology and simulation strategy. Section 5 presents the results, including their sensitivity to key modelling assumptions. 6 , 7 discuss our results and provide conclusive remarks respectively.

2. Tourism industry in Scotland and COVID-19 policies

2.1. the economic role of tourism in scotland pre-pandemic.

Tourism is an important economic sector for Scotland: indeed, the Scottish Governments' Economic Strategy ( Scottish Government, 2015 ) identified tourism as a sector where Scotland has a distinct comparative advantage. The statistics bear out this sector's economic importance. In 2019, around 8.8% of employment and more than 15,000 registered businesses in Scotland were in the tourism industry, 1 contributing around £4.5 billion to Scottish gross value added.

Another perspective on tourism in Scotland comes from an analysis of the spending behaviour of tourists. Table 1 shows spending in Scotland by tourists' place of residence and whether the trip is an overnight or day trip for the most recent (pre-COVID) year of 2019, and shows that a total of £11.64 billion was spent by tourists in Scotland in that year. Comparing the totals of the first and second columns we can see that total day trip expenditure is only around £90 million lower than spending by tourists who stayed overnight. This reflects a greater frequency of overnight trips and the importance of day trips in tourist spending, which is dominated by Scottish residents (77% of total spending on day trips in 2019). We can see how the pattern of spending by place of residence is reversed in the case of overnight trips. Here, those residents living outside of the UK provides the largest element of expenditures and comprised 43% of the total spending on overnight tourism.

Tourist spending in Scotland by place of residence, 2019, £millions.

Sources: Visit Britain, 2020a , Visit Britain, 2020b and Office for National Statistics (2020) Notes: “Day trips” relate to all tourism day trips, e.g., non-regular activities, outside the place of residence) and so differ from leisure trips. Some totals may not match those in other UK sources due to inclusion of spending which cannot be matched to place of residence in the latter publications. Any errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

2.2. A timeline of key events on COVID-19 impacting travel and tourism in Scotland during 2021

Since the identification of the SARS-Cov-2 virus in late 2019 the most immediate non-health interventions were felt through restrictions on travel: the introduction of stay-at-home orders, region- and city-specific lockdowns and the closure of borders. In Scotland, the first positive case was recorded on the 28th of February 2020, and public health measures were immediately put in place. 2 Public heath advice, restrictions and guidance have evolved in line with the number of cases, hospitalisations, and deaths, the capacity in the health system, the identification of any new variants of COVID-19 and (since December 2020) the roll out of the vaccination programme. 3

The restrictions impacting on tourism activity in Scotland through 2021 can be divided into three distinct phases. First, from the 4th of January until April, Scotland was in its second national lockdown, initially from the rise in the spread of the Alpha variant in late December 2020. In this phase there were restrictions on all travel (international and internally between local authorities in Scotland) for all but essential business, with the Scottish population under a “stay at home” order. By the middle of February, the Scottish Government 4 announced the plan for relaxing lockdown restrictions on an authority-by-authority basis in response to changes in closely watched indicators, including case numbers.

The second phase – roughly from April until July - saw the gradual unlocking of restrictions, the return of in-person schooling for all age groups, and the recommencement of non-essential journeys (including tourism trips). Initially, such trips were only permitted within a resident's local authority area, with movements between local authorities relaxed from 16th April. Subsequently, hospitality was permitted to reopen in some areas from the 26th of April, with restrictions in place including the use of “Track and Trace” for customers, and rules on ventilation and social distancing between individuals and staff in indoor settings. By July, all of Scotland's local authorities had moved “beyond Level 0”, which permitted wider travel within Scotland and the UK. In the third phase, from August until December, guidance remained in place for testing, the continued rolling out of booster vaccines and, from October, the use of vaccine certificates for entry to some events and venues.

During 2021, rules on international arrivals (set for the UK as a whole) placed a burden on the traveller to comply with the rules in place at the time. For those arriving in the UK from overseas, their origin country would be on either a “green”, “amber” or “red” lists which set out the required process to be followed. The required restrictions for arrivals depended on the list the origin country was on, which were based on coronavirus rates in those countries, and the passenger's vaccination status, among other considerations, and set out the requirements for pre- and post-travel testing and/or quarantine. From May 2021, arrivals from “green” list countries had quarantine-free travel to the UK, while restrictions for travellers from “amber” countries were dependant on their vaccination status. As of June 2021, most countries which UK nationals visited overseas were on “amber” or “red” lists, which was expected to significantly dent international tourism activity to and from the UK ( Office for National Statistics, 2021a ). From August onwards, countries were gradually moved towards green and amber lists, as case numbers fell, opening up the possibility for travel to and from the UK. From October, for instance, fully vaccinated travellers arriving from countries outside of the “red” list required proof of vaccination, and did not need to provide a negative test upon arrival. By October, the UK government replaced the “amber” and “red” lists with a “rest of the world” list ( UK Government, 2021 ), while from November, no country was on the “red” list, which was subsequently dropped in December 2021.

3. Economic modelling of impacts of COVID-19 and tourism

The literature on specific episodes of tourism crises is quite developed for specific events such as natural disasters – where tourists may avoid an impact area due to not wanting to hinder the recovery effort, for instance Rosselló, Becken, & Santana-Gallego (2020) – and for identifying “breaks” in tourism series linked to such events ( Cró & Martins, 2017 ). A variety of papers have examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic using computable general equilibrium models. Keogh-Brown, Jensen, Edmunds, and Smith (2020) look at the impact of COVID-19 on the UK in 2020 through health, virus mitigation and suppression scenarios. Each simulation introduces a disturbance affecting productive labour supply and factors of production employed in tourism and other “non-essential” activities. Walmsley, Rose, and Wei (2021) explore different mechanisms through which the COVID-19 pandemic could affect economic activity, including closure of businesses, and increased morbidity. They find that reductions in demand due to the inability to spend could offset policies which reduced the ability of businesses to trade and limited social interactions.

Other papers have sought to identifying channels through which sectorally-defined disturbances impact on the wider economy. Porsse, Souza, Carvalho, and Vale (2020) use a dynamic interregional computable general equilibrium model of Brazil to quantify the consequence of COVID-19 impacting through labour supply and the reduction in output of specific activities. They introduce output reductions of 50% in sectors where social distancing can be maintained and 100% in sectors where this is not possible, including transport and accommodation. In a similar vein, Wang, Meng, Siriwardana, and Pham (2022) look at the impacts on China of a combination of shocks related to COVID-19, including to labour supply, investment, and household consumption, as well reductions in inbound and domestic tourism demand. In their “non-control” scenario, they forecast the same reduction in domestic tourism demand and inbound tourism, with a smaller reduction in domestic tourism in a scenario where policies act to reassure tourism demand.

We find a smaller number of papers which isolate the pure direct impacts of changes in tourism from the COVID-19 pandemic and the policy response using computable general equilibrium models. The majority of these focus on a single country. For instance, of the peer-reviewed published papers, Deriu, Cassar, Pretaroli, and Socci (2021) focuses on Sardinia, Henseler et al. (2022) on Tanzania, Wang et al. (2022) on China, Malahayati, Toshihiko, and Lukytawati (2021) on Indonesia and Pham et al. (2021) on Australia.

An exception is the early work of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2020) which takes a global approach and was also one of the first analyses in 2020. This paper assumes that COVID-19 directly impacts on two sectors - accommodation, food and services and recreation and other services - through simulations corresponding to output reductions of 80% for 5 months, 80% for 10 months and 100% for 12 months in “moderate”, “intermediate” and “dramatic” scenarios. In their scenarios, global gross domestic product in 2020 falls by between $1.2 trillion and $3.3 trillion, with countries where tourism provides a large share of gross domestic product most heavily affected in percentage terms, such as Jamaica, Thailand and Croatia, with the largest absolute impacts in the USA and China. However, this paper is limited in that the dataset used does not have information to identify inbound tourism spending, which in their dataset is aggregated with exports.

The recent single-country studies mentioned above focus predominantly on reduction in inbound tourism. For instance, Pham et al. (2021) , analyse the consequence of the projected reduction in inbound tourism demand in 2020 for Australia in a short-run framework where capital stocks are fixed, and nominal wages remain unchanged. Their estimate of the direct shock to tourism spending is calculated from a Tourism Satellite Account, which then becomes the disturbance modelled in the computable general equilibrium framework. Henseler et al. (2022) explore how various international channels of transmission, including a drop in inbound tourism, could affect the Tanzanian economy.

However, the response of inbound and domestic tourism could be different in the face of a disaster. As Hall (2010, p. 410) notes “there is a need for much greater attention on the effects of crises on domestic tourism, which on a global scale makes up the vast majority of tourism anyway, and the extent to which it may be able to compensate for the loss of international revenue.” This is particularly relevant as the domestic tourism may return more quickly than inbound tourism as countries ease their lockdown restrictions. Whilst it is perfectly sensible to focus on international channels for regions and countries that rely primarily on external arrivals such as in the case of Henseler et al. (2022) , for regions with potentially strong domestic demand for touristic activities especially in times where inbound travel is restricted, it is fundamental that domestic demand is considered as well ( Arbulú et al., 2021 ).

For this reason, in this paper we extend the previous studies such as Henseler et al. (2022) and Pham et al. (2021) to consider the system-wide impact of changes in domestic alongside inbound tourism spending. We are primarily concerned to see what additional impacts the loss of domestic demand brings. The critical issue in such models is then three-fold. First, how has COVID-19 impacted on tourism activity in Scotland in 2021, and are there differential impacts across inbound and domestic tourism categories? Second, how can such impacts be appropriately captured in a computable general equilibrium model of Scotland? Third, what are the wider impacts on the whole economy of COVID-related changes through the tourism industry? We set out our methodology to answering these questions in the next Section.

4. Methodology

4.1. computable general equilibrium model.

We model the system-wide impacts of COVID-19 disruptions to tourism in Scotland by using a computable general equilibrium model of the Scottish economy. The computable general equilibrium framework is ideal for the simulation of the economy-wide consequences of shocks which impact on a particular sector (or sectors) of an economy, but which could have wider impacts (see for instance, Meng & Siriwardana, 2017 ). There are three elements which make computable general equilibrium a particularly useful lens for tourism analysis. First, they have a multisectoral basis and encompass the whole economy, and so are ideal for looking at shocks which impact initially on specific sectors – such as tourist-facing activities - but where there is interest in the aggregate consequences. Second, they can reflect constraints in the supply of inputs in production which could limit the ability of an economy to adapt to a shock in the short term. Third, and relating to its value as a simulation tool, they can simulate ex ante the impacts of disturbances against a counterfactual scenario, typically that of “no change”. The consequences of specific shocks can be isolated from other disturbances which might be impacting an economy, so that the pure impact of a specific disturbance can be analysed. This use as a simulation tool can be valuable in the case of an economy being impacted by several disturbances at the same time, or in the case where unprecedented, rapid and multiple policy interventions are simultaneously taking place.

Our model is based on the AMOS framework which has previously been used in several applications, including tourism (see for instance Allan et al., 2017 ). Our model considers economic transactions of 30 industries, 5 where each industry produces output using a combination of intermediate inputs and non-produced factors of production, namely capital and labour, that minimizes costs. This is represented in a nested constant elasticity of substitution (CES) production function. Domestic and imported intermediate inputs used by industries are imperfect substitutes ( Armington, 1969 ). Each industries' output is sold either domestically - to Scottish households, non-residents (i.e., tourists) and government - or exported to the rest of the UK and rest of the World.

The model's configuration reflects the specific needs of our research question in at least three crucial aspects: the dataset, the labour market and the temporal dimension of the analysis.

4.1.1. Dataset

The model is calibrated on a 30-industry Social Accounting Matrix purposely built for this project ( Allan, Connolly, Figus, & McFarlane, 2021 ). The dataset is based on the most recent annual Scottish Input-Output table available at the time of the research (for the year 2017) which was aggregated to 30 sectors. Our aggregation retains details of different categories of tourism demand, and of those sectors supplying products to tourism consumption, at the highest level of detail possible. It identifies five tourist-facing industries, namely accommodation, food and beverages services, creative services, cultural services, and sports and recreation. On the demand side, final demand in Scotland of non-residents (inbound) from the rest of the UK and rest of the World is separately identified from exports in the Scottish Input-Output table. This is an advantage compared to other studies based on the Global Trade Analysis Project database - such as United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2020) - because it allows us to model shocks to domestic and inbound tourists separately. This distinction is important not only because the magnitude of the shocks to each category will be different but also because of differences in the spending patterns by sector of these tourism categories.

4.1.2. Labour market

Similar to previous studies (for instance Pham et al., 2021 , and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2020 ), we identify two labour markets: one for high-skilled and one for low-skilled workers, each with a pool of unemployed workers. To identify high- and low-skill workers we follow the methodology outlined in Ross (2017) to split the Scottish Input-Output accounts. This uses the UK Labour Force Survey 6 ( Office for National Statistics, 2021b ) to estimate the skill level for each industry based on the highest qualifications of employees. For simplicity, any employee with a qualification at UK National Framework of Qualifications level 3 7 or higher is classified as high-skill, whereas employees with qualifications below National Framework of Qualifications level 3 are classified as low-skill. There is labour mobility between industries for workers within the same skill level. Firms employ a combination of both high- and low-skill labour but the two are considered imperfect substitutes. The total labour force (high skill plus low skill plus unemployed workers) is fixed.

4.1.3. Temporal dimension

We use a set of short-run closures in our analysis, following Pham et al. (2021) . First, we assume that sectoral capital stocks are fixed as there is not enough time for capital stocks to accumulate or decumulate. However, investment responds to changes in the value of capital, and this will have an impact on capital stocks in the following years if the shock persists.

Second, we assume that nominal wages are fixed. This is because wages do not adjust rapidly enough to have a significant impact in the first year of the shock. Third, we assume that exports are initially price insensitive. Typically, a negative demand shock would put downward pressure on the demand for factors of production which would lower their price. In our model, this would in turn reduce the costs of producing goods in Scotland relative to the rest of the world. Whilst these competitiveness effects may take place, we believe that one year is too short a period for exports to respond as a result to changes in relative prices (in addition, the COVID-19 related fall in economic activity is not only hitting Scotland, so that prices could also be falling in other countries from the pure effects of the fall in demand). Fourth, we keep government expenditure fixed, and assume that governments do not adjust current spending instantaneously following a change (reduction) in their revenue. Scotland is a devolved UK nation with a complex fiscal system and tax/spending rebalancing mechanism (see Lisenkova, Greig, McGregor, Roy, and Swales (2021) for details). This allows us to separate out the impact of the reduction in tourism demand and their propagation through the economy from any government stimulus programme.

Later in the paper, we test the importance of these assumptions for our results by running the central case scenario with two alternative closures. First, we relax our assumption of a fixed nominal wage and let wages adjust according to a conventional wage curve specification, in which wages are inversely related to the unemployment rate. In our second alternative closure, we let export demand adjust to changes in relative prices.

4.2. Model inputs: the demand for tourism before and during the pandemic

To derive the economy-wide impacts of changes in domestic and inbound tourism demand during 2021 we follow two steps. First, we estimate a baseline of tourism spending in Scotland by different categories of tourist demand in Scotland in 2019. As the year immediately preceding the pandemic, this gives us the detail of the counterfactual tourism behaviour in the absence of COVID-19 in 2021. Second, we identify the changes in each category of tourism demand during 2021 by month, relative to the “no-pandemic” baseline, which provides us with the overall changes in spending by domestic and inbound tourists in Scotland.

4.2.1. Baseline counterfactual scenario

The baseline is constructed using publicly available information and consists of monthly spending in Scotland for five tourism categories: domestic day trips, domestic overnight, rest of UK day trips and rest of the UK overnight and (non-UK) international overnight. As set out in the Introduction, we use the term “domestic” to related to the first two categories, i.e., spending by Scottish residents, and “inbound” to refer to the final three categories.

To derive the baseline counterfactual tourism expenditure in 2019 for day trips, overnight trips and international spending we use information from the Great Britain Day Visitor survey, Great Britain Tourism Survey ( Visit Britain, 2020a , Visit Britain, 2020b ) and International Passenger Survey ( Office for National Statistics, 2020 ) (see Table 1 ). The Great Britain Day Visitor survey contains information on the geographic pattern of day trip spending across Scotland's 32 local authorities averaged over the period from 2017 to 2019. We aggregate these to estimate total day trip spending in 2019 in Scotland by Scottish and rest of the UK residents. For the domestic and rest of the UK baseline we use information from Table 1 and Visit Britain, 2020a , Visit Britain, 2020b . International tourism spending estimates come from the International Passenger Survey Office for National Statistics, 2021a , Office for National Statistics, 2021b .

To disaggregate tourism spending categories by month, we use information contained in the Great Britain Tourism Survey ( Visit Britain, 2020a ). This reports monthly spending for overnight tourism but not for day and international tourism. Thus, we assume that the spending patterns for overnight also apply to day trips and international. 8 Applying these adjustments, we can show our resulting pattern of spending by tourism category across the months of the year ( Fig. 1 ), from which we can see the important peaks of tourism spending in July and August, coinciding with the northern hemisphere summer.

Monthly breakdown of tourism spending in Scotland in 2019, £m.

Source: Author’s calculations based on VisitScotland (2021) and VisitBritain (2020a) .

4.2.2. Central scenario calculation

Our central scenario for 2021 is based on observed changes in travel and tourism behaviour during that year. Recall from Section 2.2 that public health restrictions in Scotland eased over the first half of 2021, from a national lockdown which lasted until April, and the subsequent return of movement permitted between local authorities with the return of some international travel from August onwards. In the absence of real-time monthly tourism spending data, we calculate monthly changes for tourism spending in 2021 relative to our pre-pandemic counterfactual by looking at three indexes, which we match to different categories of tourism spending: day trips, overnight and international. Here we set out how we calculated the changes in these indexes during 2021 relative to their pre-pandemic levels.

Changes in spending in Scotland by (Scottish and Rest of the UK) day trip tourists in 2021 are estimated using monthly fuel sales in Scotland data from the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy ( Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, 2021 ) (see Fig. 2 ). 9 To isolate fuel used for day trip purposes, we calculate an “essential fuel use” baseline from the observed data during the lockdown period between January and March 2021. This is then subtracted from total fuel used over the rest of the year, under the assumption that the fuel used during the full lockdown represents the level of fuel consumption that persists in the absence of any other movements. 10

Scottish monthly fuel sales, litres, January 2018 to December 2021.

Source: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2021)

For changes in spending in Scotland by (Scottish and Rest of the UK) overnight tourists in 2021, we set the overnight spending between January and April to zero (i.e., a 100% reduction from 2019). From May onward, we use data from the monthly series on room occupancy in Scotland ( VisitScotland, 2021 ) (see Fig. 3 ). 11 We calculate the room occupancy ratio between comparable months in 2019 and 2021 to see changes in the level of hotel use during 2021 relative to the pre-pandemic levels by month. We adjust for the changes in pricing by multiplying the room occupancy rate by the average room rate, to get the change in spending relative to 2019.

Scottish monthly room occupancy rate for all accommodation services, March 2019 to December 2021.

Source: VisitScotland (2021) .

To calculate the change in spending in Scotland from international tourists in 2021, we use monthly data on international passenger numbers at Scottish airports (see Fig. 4 ). Similarly to the other two categories, we calculate an “essential travel” baseline from the data between January and April (the lockdown period) and subtract this from each monthly value for 2019 and 2021, before calculating the change in the monthly values between these two years from May 2021 onwards (when non-essential international travel could return). For instance, in August 2021 (adjusted) passenger numbers were 16% of their value in August of 2019 (an 84% reduction). Finally, we note that our use of passenger data as a proxy for spending assumes the reduction in international spending is proportional to the reduction in passenger numbers, in the absence of better information.

International terminal passengers at airports in Scotland by month, 2019 to 2021.

Source: UK Civil Aviation Authority (2022) .

Using each of these monthly series, the calculated reductions of tourism spending in Scotland by category and month in 2021 related to the pre-pandemic levels is presented in Table 2 .

Reduction in fuel sales, room occupancy and international travel by month during 2021 relative to adjusted pre pandemic baseline.

Source: Authors calculations.

4.3. Annual shocks and computable general equilibrium simulation strategy

We aggregate changes in spending at the monthly level by our five different tourism categories (as set out in Section 4.2.2 ) to a set of total demand shocks for 2021. A summary of the shocks is presented in Table 3 . We estimate that in total, Scotland saw a £6.3 billion (in 2017 prices), or 54.3%, reduction in all tourism spend in 2021 compared to the pre-pandemic baseline. This is introduced to the computable general equilibrium model through a direct shock to final demand, which subsequently captures how this shock propagates across the Scottish economy.

Summary of simulations input.

Source: Authors' calculation.

The total shock is distributed across sectors of the Scottish economy in proportion to the spending by each category ( Scottish Government, 2021b ). Spending patterns by sector (what each category of tourist purchases from Scottish industries) depend on the type of tourist category, for example day trip tourists will not spend money on accommodation. The simultaneous reduction in domestic and inbound tourism demand constitutes our central case scenario. To demonstrate the different impacts that reduction in domestic and inbound tourism demands have, and facilitate the interpretation of results, we present economy-wide results for the two shocks separately and together.

Domestic changes (both day trips and overnight) are introduced as a reduction in household consumption. This occurs as within the standard Scotland Input-Output table, tourism spending by Scottish residents is included in the household spending column. However, domestic demand is endogenously linked to income and is price responsive. Thus, we introduce a wedge between disposable income and final demand by calculating a price increase that would deliver the desired reduction in household demand. 12 The difference between disposable income and final demand is then considered as savings and these are exogenous in the model, as (following Lecca, McGregor, & Swales, 2013 ) we do not assume that savings equal to investment in the short run. Inbound tourists' income is exogenous to our single region model and so it is possible shock international tourism demand directly.

5.1. Central case scenario: aggregate impacts

Table 4 presents the results of reduced tourism demand on key macroeconomic indicators in our central case scenario. These are short-run results that represent the first year of the shock, which is assumed here to be 2021. It is important to recall that the total final demand shock is a combination of two different shocks, one to inbound tourism spending and one to domestic tourism spending. These shocks are aggregated in the “All” simulation in Table 3 , with the results presented in the final column of Table 4 .

The economic impact of tourism demand reduction in 2021 on key macroeconomic indicators, % changes from base unless otherwise specified.

Source: Authors' calculations. Note: absolute numbers for gross domestic product and employment changes are rounded to the nearest £100 million and 1000 respectively.

The fall in domestic and inbound tourism demand due to COVID-19 restrictions leads to an overall reduction in economic activity, indicated by a 1.76% fall in gross domestic product. Firms adjust their output to accommodate lower demand. The lower output leads to a reduction in the requirement for capital and labour. Whilst capital stocks are fixed in the short run, their value falls, causing a sharp reduction in investment. However, labour demand falls by 3.83% and the unemployment rates increase by 3.63 percentage points. 13 Unsurprisingly, there is a larger impact on low-skill employment (which falls by 5.10%) over their high-skill counterparts which reduces by only 2.78%, due to the nature of industries that are directly adversely affected by the shock employing a greater proportion of low-skill labour.

The loss of labour and of value of capital results in lower income within the economy. This affects households' disposable income, which falls by 1.50%. However, the overall reduction in demand puts downward pressure on domestic prices, resulting in a decrease in the Consumer Price Index by 1.49% which in turn leads to an increase in the real wage by 1.51%. Recall that in this scenario we are keeping the nominal wage fixed. This partly dampens the erosion in household nominal income. However, due to restrictions in activities liked to COVID-19, households' consumption falls by 4.36%, whilst households' net savings sharply increase (62.54%). Since the model assumes that exports are price irresponsive in the central case, the fall in prices – which would otherwise improve the competitiveness of Scottish products - has no impact on exports. Government expenditure is held fixed. However, government revenues (from taxes) fall by 2.62%.

The first and second columns of Table 4 present results from simulations where domestic and inbound tourism demands are shocked individually. The qualitative impact of results is comparatively similar to when these shocks are aggregated. However, it is interesting to notice that the reduction in inbound tourism has a larger overall impact. Moreover, the overall impacts (in the “All” simulation) are slightly larger than the summation of the two individual shocks, due to the ripple effect that one has on the other.

5.2. Central case scenario: sectoral results

The macroeconomic results can be decomposed at the sectoral level, to see what industries are expected to be more impacted by the fall in tourism demand. Fig. 5 reports the absolute change in employment expressed in full time equivalent jobs. The combined reduction in domestic and inbound tourism demand leads to a potential loss of 100,000 jobs ( Table 4 ). These are primarily concentrated in the food and beverage services and accommodation services sectors, which together account for approximately 56% of the aggregate employment loss. The decomposition of the shock between domestic and inbound demonstrates that the accommodation services sector is particularly impacted by the reduction in inbound tourism, as domestic tourism is mainly based on daytrips, while the food and beverage services sector is impacted roughly in similar ratios as other sectors. The wholesale and retail sector is the third most impacted sector while the other 27 sectors account for approximately 29% of the employment loss.

Absolute change in employment by industry, full time equivalent.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Fig. 6 reports the change in value added by industries. Value added is defined as the contribution of labour and capital (factors of production) to the value of a product and is directly dependent on the total production in the economy. As demand falls, output decreases and so does sectoral value added. The resultant shock leads to a reduction in value added of about £2500 million, of which 48.3% is concentrated in the food and beverage services and accommodation sectors (approximately £1.2 billion). Wholesale and retail contributes an additional £378 million loss and these three industries together account for a total of 63% of the aggregate loss in value added across the Scottish economy. Land transport services, public admin and health and construction services account for a further 15% of the total loss.

Absolute change in value added by industry, £millions.

5.3. Impact of alternative model specifications

The results presented in 5.1 , 5.2 are sensitive to the modelling decisions made to reflect short-run economic impacts of the changes in tourism demand. However, given the level of complexity with which COVID-19 impacts the economy, it is difficult to understand whether a degree of price responsiveness is likely to take place in the aftermath of the shock or in subsequent years. For this reason, we relax the assumptions of 1) fixed nominal wage and 2) export price inflexibility, in a separate set of simulations and use these as sensitivity checks. Results are presented in Table 5 . We look at three alternative model specifications and compare to our central case scenario: the first (“Endogenous exports”) considers the case where exports react to changes in relative prices; the second (“Endogenous wage”) considers a situation where wages adjust according to a conventional wage curve; the third combines both endogenous wages and flexible exports. In all three specifications, we repeat the same shocks to both domestic and inbound tourism final demand used in the previous section (“All”) so that they are directly comparable and that all changes in results can be attributed to the different model specifications.

Sensitivity of results to changes in macroeconomic closures.

Source: Authors' calculations. Notes: 1. the first numerical column in this table corresponds to the third numerical column in Table 4 ; 2. absolute numbers for gross domestic product and employment changes are rounded to the nearest £100 million and 1000 respectively.

When exports are sensitive to change in relative prices (column 2), the demand for Scottish products from the rest of the world and the rest of the UK increases by 1.22% and 1.15% respectively due to the reduction in Scottish prices. This increase in exports helps to cushion the impact of the reduced tourism demand, thus the gross domestic product reduction is smaller than the “central case scenario” and gross domestic product falls by 1.50% rather than 1.76%.

When wages adjust according to the wage curve (column 3), nominal wages fall by 5.43%. With fixed capital stocks, cost minimising firms reduce their use of the non-fixed input (i.e., labour), thus unemployment increases, and wages fall. This has three consequences. First, household's nominal income is impacted by the lower wage. Thus, consumption falls by 5.55% as opposed to 4.36% in the central case scenario. Second, the cost of labour falls. This is reflected in an overall reduction in the prices of Scottish goods, which then positively affects other components of final demand, including capital formation. Investment falls by 4.96% compared to 6.84% in the central case scenario. Finally, Scottish firms and consumers partly substitute imports in place of Scottish products. Thus, gross domestic product reduces by 0.62%. The combination of both flexible wages and exports (column 4) further dampens the negative impact, as demand for exports increases by approximately 2.09%. In this case, gross domestic product only falls by 0.41%.

6. Discussion

The results demonstrate that COVID-19 related changes in tourism spending have serious economic consequences for a region like Scotland where tourism is an important sector. Whilst there is no certainty that these will be the actual impacts on the economy - given that a series of other forces that are operating simultaneously in the economy have not been considered - we are able to draw some lessons and recommendations for the future.

First, the reduction in inbound tourism demand has a larger impact than the reduction in domestic demand. This is for two reasons. First, in our modelling we expect inbound tourism demand (which includes spending by residents of the rest of the UK) to experience a slightly greater contraction in expenditure ( Table 3 ). Second, domestic tourism demand has a greater content of imported goods, thus the impact of its reduction partly spills over internationally (i.e., through reductions in spending on goods produced outside of Scotland), and it is not captured by our single region model.

This contradicts the view that the loss in inbound travel can be compensated fully by an increase in domestic tourism. The previous work of Bonham, Edmonds, and Mak (2006) suggests that domestic tourism trips can be substitutes for inbound trips. However, non-UK residents spending in Scotland in 2019 was over £2.5 billion ( Table 1 ), which is equivalent to almost 50% of spending on tourism activities by Scottish residents in Scotland. Domestic tourism spending would therefore require to increase substantially if it was to mitigate the lost inbound tourism expenditure. Further, we know that the spending patterns of Scottish and non-Scottish residents are very different, so that even if total spending was maintained, spending across sectors would be different and this would have positive and negative knock-on effects on different sectors. For instance, our results show that the accommodation services sector is much more reliant on inbound spending.

This result is not only consistent with Boto-García & Mayor (2022) and Duro et al. (2022) that find mixed support for the role of domestic tourism demand in creating regional resilience in regional tourism, but it provides a further explanation for their finding in the different demand composition of domestic and inbound tourists. In the case of Scotland for instance, we find that one pound spent by international tourists has a larger macroeconomic impact than one pound spent by domestic tourists because domestic spending has a higher import content. Thus, an understanding of the composition of demand by different categories of tourists is fundamental in determining their economic contribution.

As one of the first papers which has considered the economy-wide impact on COVID-19 on the impact separately on inbound and domestic tourism activity and spending, it is difficult to directly compare our results to others which have focused purely on inbound tourism. Indeed, this focus on both categories is fundamental to exploring the extent to which increased domestic tourism could mitigate the impacts of losses in inbound travel as we note above. In this sense, our framework offers a suggestion to studies of the impacts of pandemics on tourism beyond either regions or Scotland. The use of a computable general equilibrium framework which is explicitly built on a set of Input-Output tables means that structural characteristics of the tourism economy in the country under consideration, including its size and embeddedness into the rest of the economy, can be captured. These will be critical for the propagation of shocks from changes in demand to the whole economy impacts and will reflect country- or region-specific details of the nature of the tourism economy.

Second, these short-run results give a series of indications about the direction of potential future impacts. We focus on household savings, employment, government revenue and investment in our results discussed above. The increase in household savings indicates that (at the aggregate level, and ignoring any distributional concerns which could be significant) the economy has built some resilience that can be used in the future to replenish consumption and help economic recovery, provided that these funds are spent domestically. We may expect for instance that if international travel remains uncertain Scottish residents may decide to spend their holiday budgets in Scotland. However, if the spending is directed towards sectors that are not directly tourist-facing, the sectoral composition of spending will change and so will output.

Our model suggests a significant reduction in employment. Being now 2022, we know that this is likely going to be less substantial. This is for several reasons, including the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (more commonly termed “furlough”) that has preserved a significant portion of labour income and protected workers from job losses during the COVID-19 pandemic. This UK-wide scheme has been an especially important element for tourism sectors. For instance, in June 2021, 22% of employment in the accommodation and food services sector was on furlough ( Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs, 2021 ). However, should these shocks become recurring and/or persistent we may see an actual reduction in employment that goes in the direction of our simulation. Nevertheless, by focusing on the pure consequences of changes in tourism demand during 2021 we can isolate the knock-on effects across the whole economy from the other factors which will have affected the Scottish economy, including the policy response including the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme.

Our model calculates a loss in government revenue in all scenarios from reduced tax income. Whilst we do not expect the Government to adjust public expenditure in Scotland instantaneously, this could impact the level of public services or taxation in the medium and long-term depending on the speed of the recovery from COVID-19. Finally, the initial reduction in investment indicates that capital stocks may start to decumulate in the subsequent years. This would increase the value of these stocks and partially reduce any initial gain in competitiveness driven by the overall reduction in Scottish prices relatively to the world prices.

7. Conclusions

In this paper we have sought to examine how the disruption to tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic could be quantified in terms of lost tourism expenditure and the subsequent economy-wide consequences using a computable general equilibrium model. In addressing this, we have developed a detailed framework for spending by different tourism categories – domestic and inbound day and overnight tourists, respectively – disaggregated by month and location of spending to calculate the change in tourism expenditure in Scotland throughout the COVID-affected year of 2021. We have shown how the easing of public health restrictions over the course of the year are reflected in changes in proxies for tourism spending, and how these can be used to provide the inputs to demand-side simulations in a computable general equilibrium model.

In our calculations, the changes in restrictions and tourism behaviour during 2021 led to a reduction in tourism spending in Scotland of 54.3% (relative to pre-pandemic levels) which translates to a reduction in gross domestic product of 1.76% (or £2.4 billion in absolute terms, in 2017 prices), and puts at risk 100,000 jobs throughout the economy. The most important sectors for the employment fall are, perhaps unsurprisingly, food and beverages services and accommodation, however negative effects are felt on employment across all sectors of the economy. We show that in all cases where we vary the model specification that the economic impact is always negative.

Crucially, we show that for the case of Scotland, the reduction in inbound spending tends to have a greater economic impact than the reduction in domestic tourism spending due to the composition of non-domestic spending which consists of a higher proportion of Scottish goods. This indicates that whilst additional spending by Scottish families may help to offset the loss in inbound travel, it is unlikely to be sufficient to completely mitigate the effects of the fall in spending by non-residents.

This research provides further lines for enquiry. First, our results assume that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry is only felt through changes in tourism demand. We know that the major consequence of a health pandemic comes through changes in labour supply, so to the extent that we omit this route, we would underpredict the direct negative consequence on the tourism industry of the pandemic. Second, we do not currently consider any policy response mitigating the changes in tourism spending (see for instance, the proposals by the Scottish Tourism Recovery Taskforce (2020) ). To the extent that policy actions might have encouraged additional domestic tourism in place of Scottish residents taking holidays abroad, our results would overpredict the hit to tourism spending. Our analysis reinforces that changes in domestic and inbound spending by tourists should be watched closely as this will be critical for the medium and long term consequences of COVID on the global tourism industry.

Funding sources

This work was undertaken with funding from the ESRC through the “UKRI Ideas to Address COVID-19” call (Grant reference: ES/W001195/1).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge comments and suggestions from participants at Fraser of Allander Institute modelling workshop (online, May 2021), European Regional Science Association conference (online, August 2021) and the International Association of Tourism Economics conference (Perpignan, June 2022) as well as input from Chris Greenwood and Raymond Macintyre (VisitScotland) and Kevin Brady (Scottish Government). Furthermore, the authors are grateful for the comments of four anonymous reviewers. For the purposes of open access, the authors have applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Editor: Lorenzo Masiero

☆ Grant Allan, Kevin Connolly, Gioele Figus and Aditya Maurya are all based in the Fraser of Allander Institute and Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow (Scotland). They all have research interests in applied regional analysis and multisectoral modelling, including Input Output and Computable General Equilibrium techniques, and in the application of these to policy-relevant issues, including tourism, energy, trade and fiscal policies.

1 The figures reported above related to Scottish Government's “preferred definition of tourism related industries” termed “Sustainable tourism” and differs slightly from the Office for National Statistics internationally comparable “Tourism Industries” measure. Both metrics identify specific industries as “tourism” based on the Standard Industrial Classification.

2 A much more detailed and regularly updated timeline of Coronavirus in Scotland is available online here: https://spice-spotlight.scot/2021/08/27/timeline-of-coronavirus-covid-19-in-scotland/

3 The evolution of travel and public health restrictions in Scotland, Wales and England can be found at the Coronavirus Government Policy Tracker ( Hale et al. (2021) . This section provides a brief overview of the key developments in public health measures during 2021.

4 The initial levels approach was set in October 2021 (Scottish Government, 2021, https://www.gov.scot/publications/covid-19-scotlands-strategic-framework/ ). This consisted of four levels, where 4 indicated a full lockdown and 0 a minimum level of restrictions and it was applied for specific local authorities based on the evolution of the spread of the virus.

5 We use the terms sectors and industries as synonyms.

6 We use data from 2017 to 2019 to increase the sample size for Scotland.

7 National Framework of Qualifications levels 3 and above correspond to qualifications achieved after the UK minimum mandatory education period (11 years).

8 This is done in absence of better information. However, should better data become available, we are able to update our estimates.

9 As the series is published in litres we do not need to adjust for inflation, however over a longer period we would expect that changes in the efficiency of the vehicle fleet would make it necessary to adjust this metric to take account of the distance equivalent of the fuel consumption. As we are comparing the relatively short period from 2019 to 2021 we assume an unchanged vehicle fleet, so that we can use the series on fuel sales as a proxy for movement.

10 Recall that during these months the Scottish Government issued a ‘Stay at home’ order, limiting all but essential travel.

11 Although this is a very good proxy for spending by overnight tourists, one limitation is that it is published with a lag of approximately four months.

12 This is conceptually equivalent to the “phantom tax” used by Walmsley et al. (2021) (and introduced by Dixon and Rimmer (2001) ).

13 Note that this implies that if foreign workers become unemployed they stay in the country. However, it may be the case that they decide to return to their home country thus leaving the Scottish labour force.

- Allan G.J., Connolly K., Figus G., McFarlane J. 2017 social accounting matrix for Scotland, University of Strathclyde. 2021. [ CrossRef ]

- Allan G.J., Lecca P., Swales K. The impacts of temporary but anticipated tourism spending: An application to the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games. Tourism Management. 2017; 59 :325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.08.014. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arbulú I., Razumova M., Rey-Maquieira J., Sastre F. Can domestic tourism relieve the COVID-19 tourist industry crisis? The case of Spain. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management. 2021; 20 doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100568. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]