- Operated by Occupational & Physical Therapists

- All Categories

- New! Products

Customer Service:

1-800-827-8283

How to choose the best wandering alarm for dementia patients [updated for 2022].

It's common for a person living with dementia to wander or be confused about their location. As scary as that is for a caregiver who can’t find a patient, it’s even more frightening for the patient, who might truly not have any idea where they are as things slowly become less and less familiar to them. Some common reasons patients wander , and can benefit from anti-wandering alarms, are confusion about where they are, delusions about what responsibility they have in their lives, escape from a real or imagined threat, and agitation, boredom, or restlessness. Whatever sets the patient off on an escape route, Alzheimer’s and dementia wander safety products can help keep the patient where they need to be to remain safe and comfortable.

What is a patient safety alarm?

Patient safety alarms come in many forms. All are designed to alert a caregiver when a dementia patient moves unsupervised, which can lead to the patient getting into an unsafe situation via a fall or wandering or both.

Who needs a patient safety alarm?

If there is any risk of someone wandering away from safety, or into spaces that could pose a threat of injury because of a fall or some other safety issue, a patient safety alarm will mitigate the risk and minimize the probability of an injury or worse.

What are the types of patient safety alarms?

Some alarms are attached to a piece of equipment or furniture, and some are attached to the patient. The best patient safety alarm for your situation will transmit the appropriate signal for a caregiver to intervene or remind the patient to stay put. It will also be something the patient cannot disable.

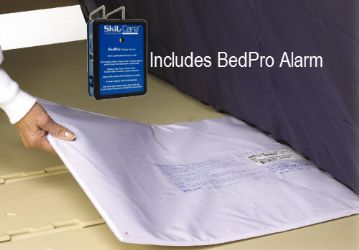

A bed alarm - some of which go under the mattress and some of which go over the mattress - is sometimes appropriate for use with chairs too. This anti-wandering alarm allows a caregiver to monitor the activity and position of a patient. With sensors that detect a reduction of pressure when patients get up, bed alarms will go off when someone is no longer sitting or laying on the bed.

- Protects patients prone to bed falls

- Alerts caregivers as soon as someone gets out of bed

- Simple to set up and use

- This style of alarm can go off if someone simply changes position, sending a false warning if someone rolls off the alarm sensor but not the bed

Best: Smart Caregiver Bed Alarm - CordLess® Alert Systems

Toilet alarm.

Toilet alarms reduce the risk of injuries due to an unassisted exit from the toilet. Pressure activated, as soon as someone rises from the toilet, the alarm will sound.

- Let caregivers know when assistance is needed

- Does not require any work or effort on the part of the patient

- Reduces risk of bathroom falls

- Alarm might not work properly if the sensor has lime and calcium scales

- Some people don’t sit on the seat when toileting so the sensor is not activated

Best: Skil-Care Gel-Foam Toilet Seat Cushion Alarm System

Best: posey toilet seat sensor, wheelchair/chair alarm.

A wheelchair alarm has a sensor that is pressure activated. When there is a reduction in pressure on the sensor from someone leaving the wheelchair’s seat, the alarm sounds. This alarm will alert to someone falling out of or getting up from the wheelchair. One design has the chair sensor or pad on top of the seat, while another kind (better for incontinent users) has the sensor placed under the seat.

- Informs caregivers when a patient rises from a wheelchair, potentially wandering into a dangerous situation

- Reminds patients who are confused to stay seated for safety

- Difficult for users to disable the alarm

- People who self-propel often shift positions in their wheelchairs, potentially setting off a false alarm

Best Wireless Alarm: Smart Caregiver Wireless Patient Chair Alarm with Pager

Best under seat alarm: skil-care underseat alarm system, fall detection device.

Not all falls can be prevented. When they happen, assistance arriving sooner rather than later can make a big difference in outcomes. A fall detection device acts as a personal alert safety system, determining when a fall has occurred, and connecting the user with help. A patient can summon help with the push of a button on a pendant, while this helpful device can make the call for assistance on the user’s behalf if they are unable to do so. For anyone at risk of a fall, this equipment provides peace of mind while helping maintain independence, knowing help will be on the way if it’s needed.

- Allows a user to be alone while still being able to summon help if necessary

- Lightweight pendant that is inconspicuous to wear and easy to use

- Acts on the user’s behalf if the patient is injured and unable to utilize the call button

- Must be worn all the time, and dementia patients might forget to keep it within reach

Best: Personal Alert Safety System - TEQ Secure for Fall Detection by SOFIHUB

A wandering alarm for dementia patients on a door significantly reduces the risk of a patient leaving a building and becoming endangered when disoriented or lost. With one part of a magnetic door alarm attached to the door frame and the other attached to the door. When the connection between the two parts is broken, an alarm will sound indicating the door has been opened. Alarms can also be attached to cupboard or closet doors to deter access to areas that are off limits because of safety concerns.

- Easy to install

- Need no electricity

- Can be used on almost any door or window without any special specifications

- Can be very loud and scary for patients

Best: Smart Caregiver Door Alarm Exit Alert System

Best: stop strip magnetic door alarm system, window alarm.

The best window alarms have the versatility to allow the window to open a bit for ventilation and fresh air without setting off the alarm. These work with sensors that are attached via a short wire. The window can be opened or closed, as long as the distance the window raises and lowers is less than the length of the wire.

- Allows for opening the window enough for ventilation

- No electricity needed

- Batteries run out and have to be monitored and changed regularly

Best: Skil-Care Door and Window Alarm with Magnetic Strip Skil-Care Door and Window Alarm with Magnetic Strip

Wheelchair alarm belt.

A wheelchair alarm belt resembles a car seatbelt, and alerts a caregiver when a patient is about to leave the wheelchair. It goes off when the belt is unfastened, providing some advance warning before the patient actually gets out of the chair. It can be the difference between preventing a fall and arriving after it’s just happened.

- Secures to all standard wheelchairs

- Eliminates sensor strips and clothing clips

- Nylon belt has an easy-release buckle for restraint-free care

- Can feel restrictive and reduce patient independence

Best: Skil-Care Seat Belt Alarm System

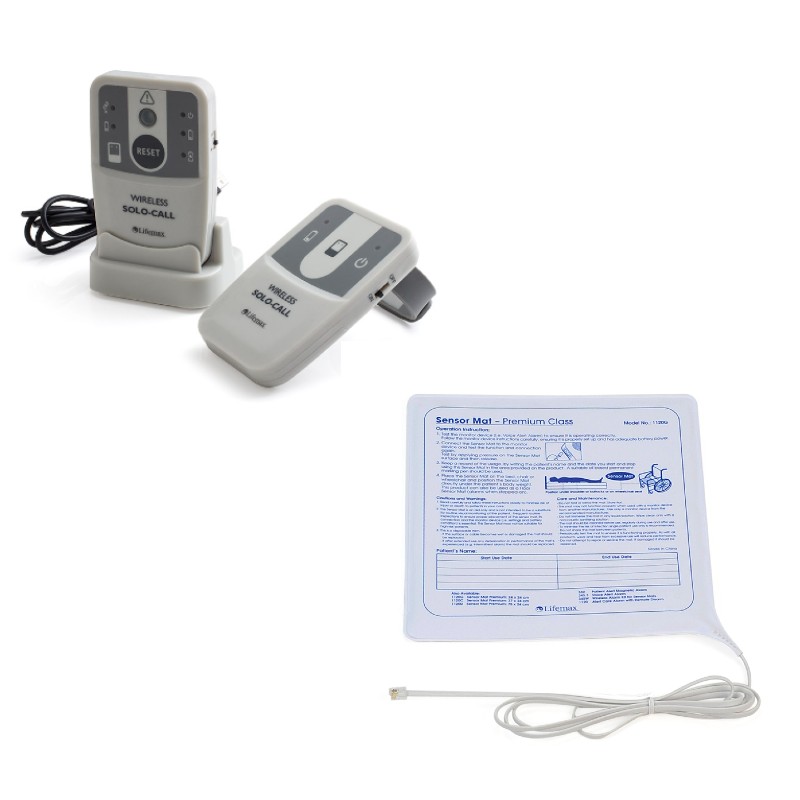

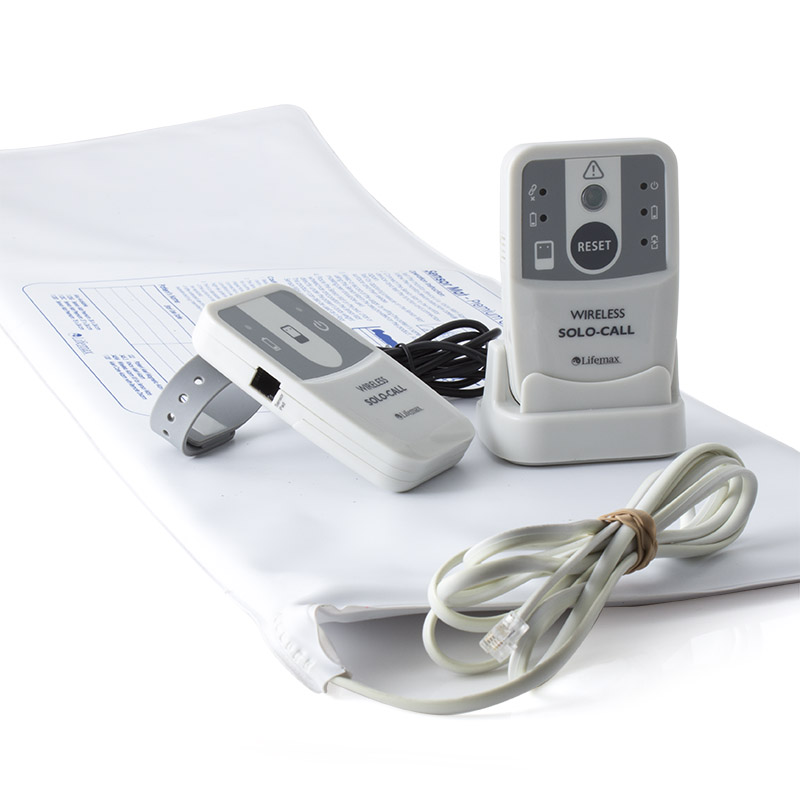

Pressure sensitive floor mat alarm.

An alarmed floor mat next to a chair or bed will alert a caregiver when a patient gets up from a chair or gets out of bed unexpectedly and steps onto the mat. The weight on the mat triggers the pressure sensors to set off the alarm so a caregiver knows to come help a patient attempting to move unassisted.

- Non-restrictive device to help keep patients from wandering away from safety

- Can be used next to the bed or a chair

- Large size available to cover large bedside area of the floor

- Might not be activated by patients who don’t weigh very much

Best: Smart Caregiver Floor Alarm Mat with Pager

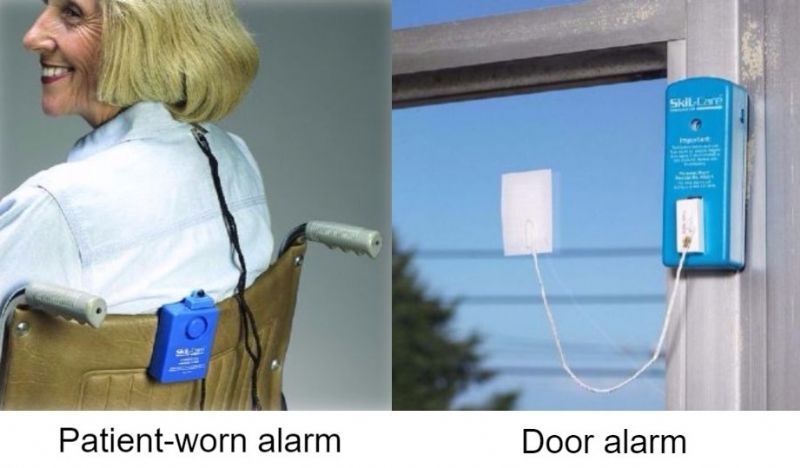

Patient-worn alarm.

Wearable patient alarms come in a variety of styles with one part of the alarm attached to a bed, chair, or wheelchair and the other part attached to the patient. If the patient goes on the move, the pull switch engages the alarm to signal a caregiver that the patient has moved away from the alarmed chair, bed, or wheelchair. These alarms might be a clip to the patient’s clothing, they could be magnet, or they could have a pull string.

- Can be used at home or while out and about

- Simple design

- Easy for a caregiver to switch off after activation

- Can sometimes be removed by patients without triggering the alarm

Best Magnetic Alarm: Advantage Magnetic Safety Alarm by Medline

Best pull cord alarm: drive medical magnetic pull cord alarm, lap cushion alarm.

Providing a useful lap cushion for a patient seated in a wheelchair, this alarm will sound if the patient tries to make an unplanned exit from the chair. This non-restrictive patient safety alarm system is ideal for use where restraint reduction is the goal. It is secured by hook-and-loop fasteners. When they are unfastened, the alarm sounds. No sensor or sensor strips are required.

- Lap pad is a comfortable positioning aid

- Does not require sensors

- Lap cushion pad is easy to wipe clean

- Bulky and can make some patients feel too hot

Best: Skil-Care Lift-Off Lap Cushion Alarm System

Features to consider.

Factors to consider when choosing an alarm to address wandering in patients with dementia include physical and mental condition of the patient, who they share their living space with, the sound level needed to alert a caretaker while not disturbing others or scaring a patient, and how adept the patient is at disabling or getting around an alarm device. Whether in a home care or clinical setting, dementia patients and their caregivers can benefit from the extra level of protection provided by these devices.

Patient Risk Level

If a patient with dementia is at risk of wandering or falling, an alarm can alert a caregiver when action is needed. An alarm that sounds when a person opens a door or window can help prevent them from leaving a safe area and exposing themselves to danger. An alarm notifying a caregiver that a patient has gotten up from a toilet or a wheelchair or sat up in bed can summon assistance to mitigate the risk of a fall.

Environment

The care setting can impact which alarm is most appropriate. Some alarms sound at nursing stations so the noise doesn’t disturb other patients who are trying to sleep.

Alert Sound

Many alarm tones can be loud and jarring, which can be very upsetting for dementia patients who can startle easily. There are alarms that allow for recording soothing voice prompts that direct the patient back to bed.

Patient-Worn or Mounted

Some anti-wandering alarms have one end attached to a bed or chair and the other end clipped to a patient’s clothing. They are activated when their movement disconnects the two elements. Others are mounted on door frames or windows or are placed on seats or on the ground. Whether they go with the patient or are in a fixed location, most are easy to install.

Cognitive Ability

Even if their memory is fading and they are sometimes confused, dementia patients often have the cognitive ability to figure out how to outsmart an alarm. If a patient has figured out how to unclip an alarm from their clothing and leave it behind or step over a floor pad sensor, alarms that are out of reach or that they can’t disable are the best option.

Urinary Incontinence

If a user struggles with incontinence, alarms that don’t have a pressure sensor they sit on or something that goes across their lap will work the best and be the most comfortable.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: are bed alarms effective.

A: Yes, and they are a big help to home caregivers because you do not have to sit by the patient's bed or stand outside their bedroom on high alert. It frees up caregivers to take care of other tasks while the patient is asleep, alerting if assistance is needed because the patient exited the bed.

Q: Do bed alarms prevent falls?

A: Bed alarm systems can reduce falls by alerting personnel when at-risk patients attempt to leave a bed without assistance. They can also get the attention of the patient to stop them from trying to get out of bed unassisted or remind them they need to be extra careful when getting out of bed.

Q: What is a Posey alarm?

A: Posey Alarms provide notification when a fall-risk patient attempts to rise without caregiver assistance. They have prerecorded messages so patients might hear family members speaking to them advising them not to get out of bed, or they can translate a soothing message in the patient’s native language.

Q: How does a bed exit alarm work?

A: Bed exit alarms warn caregivers , and in some cases patients themselves, when a patient leaves or attempts to leave the bed. They can be patient-worn or they can be pressure sensitive pads that go off when a patient moves. They warn the caregiver that the patient has changed position and is about to leave the bed, alert the caregiver that the patient has already left the bed, and remind the patient they are doing something they shouldn’t be doing.

Q: Do chair alarms work for the elderly?

A: Yes. If wandering is an issue, a chair alarm will notify a caregiver a patient is on the move. If falling is a consideration, chair alarms work best if a caregiver is close by, even if their attention is on something else. This type of alarm will give someone close enough to the patient time to be at their side to prevent a possible fall should they choose to get up from a chair.

Q:What is a wheelchair alarm?

A: A wheelchair alarm helps to monitor the activity of someone seated in a wheelchair. Typically, these alarms are either magnetic (safety belt or clothing clip alarms) or they combine with a sensor or pad (seat alarm) that detects a reduction in pressure and alerts when a patient tries to leave the chair.

Q: How do fall detection devices work?

A: Fall detection devices use accelerometers, a type of radio wave technology sensor, to monitor movement. The fall alert detectors can measure when the user has suddenly fallen by detecting the abrupt changes of body movements. The technology can evaluate an individual’s body position, physical activity, and the smoothness of acceleration of movements. If it’s determined these variables are within the danger zone, a fall alert will be sounded.

Final Thoughts

Six in 10 people with dementia will wander at least once, and many do it repeatedly, as they lose their ability to recognize familiar places and people. Wandering can be extremely dangerous, so the risk cannot be ignored. Patient Safety Alarms are a valuable tool to ensure dementia patients remain in a comfortable and safe environment.

If leaving a building is the greatest concern, a door frame model will suit your situation well. If getting up unassisted from a bed or a toilet presents an additional fall risk, a pressure sensitive alarm is a good choice. If a patient is transferred multiple times a day, an alarm that clips to their clothing and attaches to the seat or bed they’re in means they can take this safety precaution with them no matter where they are. Whether being cared for at home or in a hospital or care home setting, there is an alarm that can help keep them safe.

Thank you for reading about choosing the best Alzheimer's and dementia wander safety products. Visit Caregiver University for more helpful articles with information on providing the best care for aging loved ones and patients.

Elderly Monitoring System | Non-Invasive Remote Monitoring Plug with No Monthly Fee

Smart Sensor Senior Medical Alert System with Fall Detection | Elderly Monitoring with No Monthly Fee

Fall Prevention Monitor

Skil-Care Door and Window Alarm with Magnetic Strip

Smart Caregiver CordLess® Bed Alarm and Chair Alarm Packages

Pressure Sensitive Floor Mat with Alarm

Smart Caregiver Bed Alarm - CordLess® Alert Systems

Skil-Care Door and Window Alarm

Skil-Care BedPro UnderMattress Alarm System

Drive Medical Pressure Sensitive Chair or Bed Patient Alarm

Subscribe for caregiver university updates, shipping information, standard ground shipping, freight shipping (truck freight).

Guide to Choosing the Right Wandering Alarms and Sensors for Dementia Patients

If you have a loved one who has Alzheimer’s or dementia, or if you are a caregiver for someone with these conditions, you are probably aware that they have the tendency to wander away. It’s because wandering is a common behavior in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia. When they start to show signs of wandering behaviors, they are at a high risk of wandering away and becoming lost, which is very distressing for family members and caregivers and dangerous for the individual.

The exact causes of wandering behavior are not fully understood. It may happen to people who are searching for something or trying to get back to a certain place that they remember, such as a job or a favorite place. However, there are also some who just wander or walk away because they feel restless or agitated. [ 1 ]

If your loved ones or patients with dementia often wander and you’re worried about them being lost, there are different ways that you can do to keep them safe and reduce the risk of wandering. One example is giving them meaningful activities to do throughout the day, particularly during the time that they usually wander. Reassuring them whenever they feel lost, abandoned, or disoriented may also help. [ 2 ] Aside from that, you may also use wandering alarms and sensors, which can notify you whenever they move around.

There are many safety alarms available for patients with dementia, and they come in various forms. But all of them are designed to alert a caregiver when a dementia patient moves unsupervised, which can lead them to get into an unsafe situation. If you are interested in getting one but unsure of what to buy, we are here to help you. In this post, we are giving you a guide to choosing the right wandering alarms and sensors.

What are Wandering Alarms and Sensors?

If your patient or loved one who has Alzheimer’s disease or a different type of dementia wanders and tries to leave your home or facility, one way to keep them safe is to place door alarms, as well as bed and chair exit alarms. [ 3 ] In addition to patients with dementia, these alarms and sensors are also used for those who struggle to get around and have an increased risk of falling. It’s because a lot of falls can occur when the elderly are moving from one chair to another or getting in and out of bed. [ 4 ]

Some might think that they can simply place other locking mechanisms like a latch high up the door. However, the downside of that strategy is when an emergency occurs, such as a fire, the person inside may not be able to escape safely out of the room or house. [ 3 ] Using wandering alarms and sensors allow the person to attempt exiting through the door, but they will also alert you to his or her need for assistance.

Wandering alarms and sensors are used to protect individuals from elopement and wandering. Whether the patients intentionally attempt elopement or simply wander around to find a door, those who are at risk of going out without the needed supervision may benefit from these technologies.

In addition to that, wandering alarms and sensors can also be used to alert others for assistance. For example, they can be placed on bathroom doors as they will sound when the door is opened, letting you or the caregiver know that your loved one or patient needs assistance in the bathroom. [ 3 ]

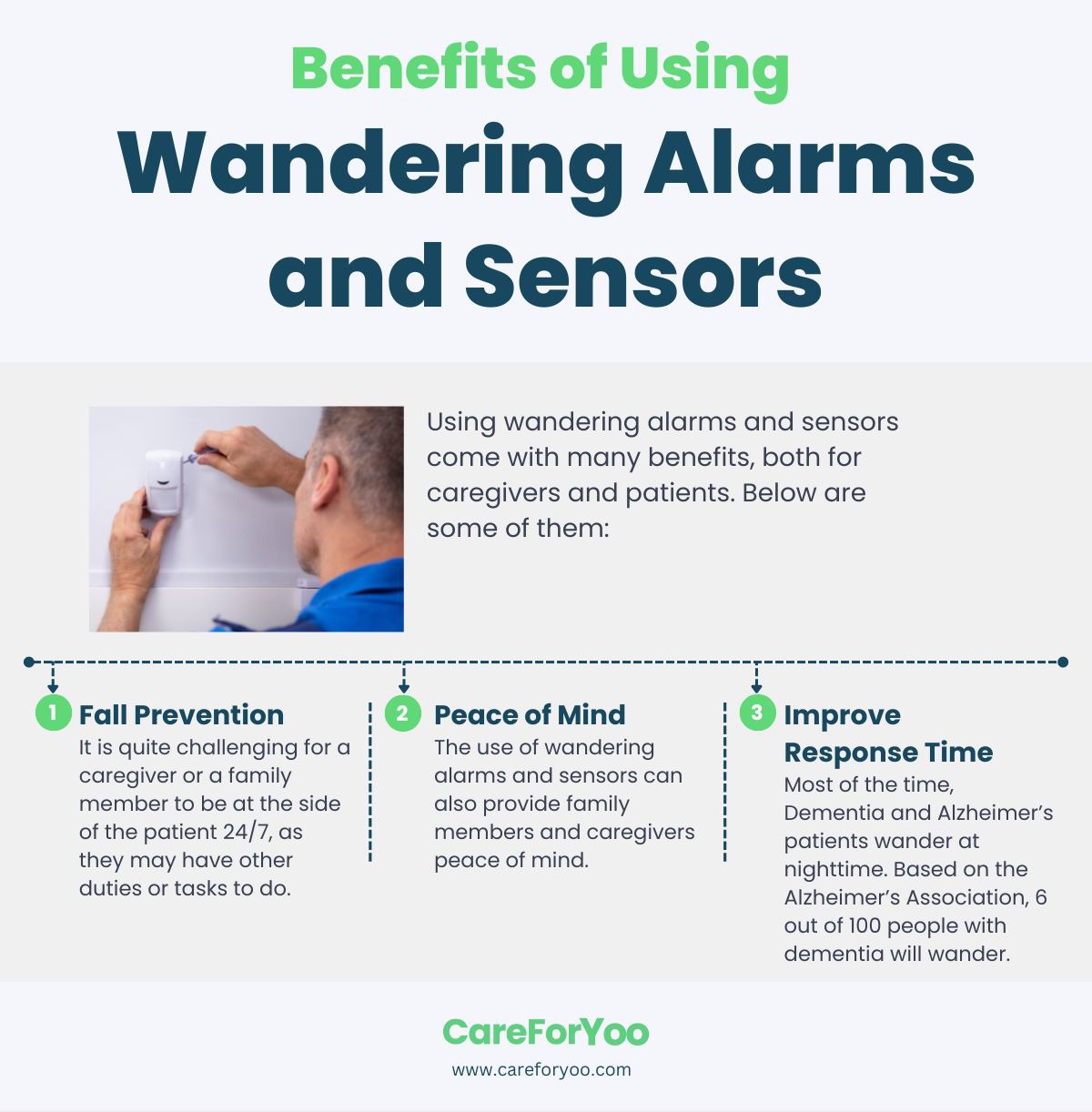

Benefits of Using Wandering Alarms and Sensors

Using wandering alarms and sensors come with many benefits, both for caregivers and patients. Below are some of them:

Fall Prevention

It is quite challenging for a caregiver or a family member to be at the side of the patient 24/7, as they may have other duties or tasks to do. If the caregiver is unaware that the patient is trying to leave the bed, chair, or room, it can lead to a dangerous situation. Therefore, investing in an exit alarm or sensor can help in reducing falls and accidents as you can always be aware whenever the patient moves around and might need help. [ 4 ]

Peace of Mind

The use of wandering alarms and sensors can also provide family members and caregivers peace of mind. With these technologies, you will be alerted when the patient has left their chair or bed or when they pass through a door. They will also let you know when the patient may need assistance but does not want to ask for help.

Improve Response Time

Most of the time, Dementia and Alzheimer’s patients wander at nighttime. Based on the Alzheimer’s Association, 6 out of 100 people with dementia will wander. Without any advanced security technologies, there can be a higher risk for wandering patients to become lost or leave the house or building without the caregiver knowing immediately. But with the use of wandering alarms and sensors, family members or caregivers will be alerted immediately, which improves the response time. [ 5 ]

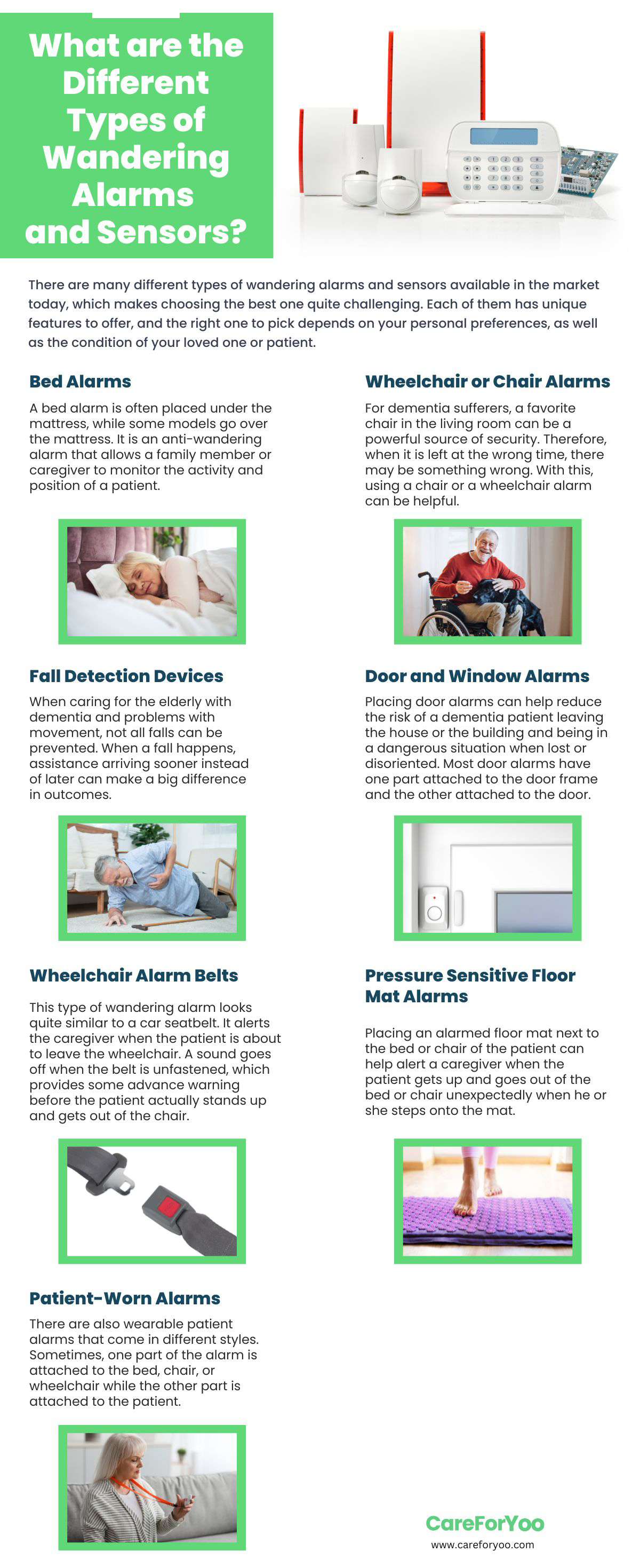

What are the Different Types of Wandering Alarms and Sensors?

There are many different types of wandering alarms and sensors available in the market today, which makes choosing the best one quite challenging. Each of them has unique features to offer, and the right one to pick depends on your personal preferences, as well as the condition of your loved one or patient. There are some alarms and sensors that are attached to a piece of equipment or furniture, while some are attached to the patient.

The best patient safety alarm for your situation will send the right signal for a caregiver to intervene or remind the patient to stay put. These alarms and sensors can’t also be disabled by patients. To help you choose the right type of wandering alarms and sensors, below are the different types and what each of them offers:

A bed alarm is often placed under the mattress, while some models go over the mattress. It is an anti-wandering alarm that allows a family member or caregiver to monitor the activity and position of a patient. The sensors detect a reduction of pressure when patients get up and leave the bed. The bed alarm will go off when someone is no longer sitting or lying on the bed. [ 6 ]

The best thing about bed alarms is that they protect patients who are prone to bed falls, as they alert caregivers as soon as someone gets out of bed. It is also very simple to set up and use. However, the downside is that some bed alarms can easily go off if someone simply changes position, which sends a false warning. But choosing a good quality bed alarm can be helpful. Below are some examples that might help you in choosing the right one:

- Smart Caregiver Wireless Bed Alarm System : This is a bed alarm system that alerts caregivers when the patient gets off the bed. It is simply placed under the patient’s back or the buttock area underneath the fitted sheet. When the patient takes their weight off the sensor pad, the remote alert monitor will notify the caregiver with a sound. It works up to 300 feet. The pad is made of soft, latex-free vinyl with a foam interior, making it comfortable. It also does not make any noise inside the patient’s room.

- Val-U-Care Safety Monitor with Bed Exit Pad : This system comes with a safety monitor and a bed sensor pad made of soft vinyl, which is easy to clean. The safety monitor features an adjustable volume and low battery light. It uses 3 AA batteries to operate.

Wheelchair or Chair Alarms

For dementia sufferers, a favorite chair in the living room can be a powerful source of security. Therefore, when it is left at the wrong time, there may be something wrong. With this, using a chair or a wheelchair alarm can be helpful. These alarms feature a sensor that is pressure activated. When there is a decrease in pressure on the sensor from someone leaving the seat, the alarm will sound and alert to someone falling out or getting up from the chair. There are chair sensors or pads that are placed on top of the seat, while others are under the seat. [ 6 ]

The best thing about wheelchair or chair alarms is that they inform caregivers when a patient rises from the chair and possibly wanders into a dangerous situation. In addition, it also reminds patients who are confused to stay seated for safety. However, people who self-propel usually shift positions often in their wheelchairs, which may set off a false alarm.

Below are some examples of wheelchair or chair alarms to help you choose:

- Lunderg Chair Alarm System : This chair alarm system has a chair sensor pad that connects wirelessly using a handheld monitor. When the patient stands up, the alarm will sound or vibrate continuously. The pressure pad is easy to wipe clean and incontinence resistant. It also includes a portable pager with an adjustable volume. It also has an improved sensor to reduce false alarms.

- Secure Safety Solutions 14CSET-1Y Chair Alarm : This chair alarm system has an 80 dB alarm sound, a flashing alert light, and a tamper-resistant reset button. The alarm also reset when the patient returns to the sensor pad. The chair sensor pad is durable and comfortable to sit on. It is best for fall-risk patients who often attempt to exit a chair or a wheelchair.

Fall Detection Devices

When caring for the elderly with dementia and problems with movement, not all falls can be prevented. When a fall happens, assistance arriving sooner instead of later can make a big difference in outcomes. Fall detection devices act as personal alert safety systems which determine when a fall has occurred, connecting the user with help.

These devices also provide patients a button that they can push to summon help. But the device can also call for assistance on the user’s behalf if they are unable to do so. This type of equipment gives peace of mind to anyone with a loved one who is at risk of a fall. It also allows the patient to be independent while still being able to ask for help if needed. The only downside is that it needs to be worn at all times by the patients. [ 6 ] Below are some examples of fall detection devices to help you choose:

- SkyAngle911FD Automatic Fall Detection Device : This fall detection device can be placed on a keychain. It is waterproof, and even when it is dropped in the water, you can still talk through it. It only has one button to press to speak with 911. If it detects a fall, it will automatically call for help. It is always in 2-way speakerphone mode.

- Mini Guardian Medical Alert System : This is a mini alarm system that can be attached to a lanyard and worn as a medical alert necklace for elderly people. It is used by simply pushing a button. It connects patients to a live USA-based and trained operator at any time of the day.

Door and Window Alarms

Placing door alarms can help reduce the risk of a dementia patient leaving the house or the building and being in a dangerous situation when lost or disoriented. Most door alarms have one part attached to the door frame and the other attached to the door. When the connection between them is broken, an alarm will sound, indicating that the door has been opened. The alarms can also be attached to closet doors or cupboards to deter access areas that are off-limits for safety concerns. [ 6 ]

Most door alarms are easy to install and do not require electricity to work. They can also be used on almost any type of door without any special specifications. However, there are some door alarms that are too loud and scary for patients. That’s why carefully choosing the best one for dementia patients is important.

Aside from door alarms, having a window alarm installed is also a good idea. The best ones have the versatility to allow the window to open a bit for ventilation and the fresh air without setting off the alarm. Window alarms work with sensors attached to a short wire. The window can be opened and closed as long as the distance between the window raises and lowers less than the length of the wire. [ 6 ] When the window is opened big, as if someone is escaping from it, the alarm will sound.

Below are some examples that might help you pick:

- Flyoukki Door Alarm Sensor : This is a battery-operated door alarm sensor that features a 120dB alarm. It does not include any wiring, allowing you to install it on any door. It has a slim design, making it discreet and simple to install.

- YisTech Wireless Caregiver Door Sensor Alarm : This is a door sensor chime that sounds to notify you when the door opens. It has adjustable volume levels from 0 dB to 110 dB, which is perfect to not startle the patient. It also has an LED indicator, and it is very easy to use.

Wheelchair Alarm Belts

This type of wandering alarm looks quite similar to a car seatbelt. It alerts the caregiver when the patient is about to leave the wheelchair. A sound goes off when the belt is unfastened, which provides some advance warning before the patient actually stands up and gets out of the chair. It can help in preventing a fall and from keeping the patient from wandering.

Most wheelchair alarm belts are secure to all standard wheelchairs. However, they can sometimes feel restrictive and may reduce the independence of the patient. But it eliminates the use of sensor strips and clothing clips. Below are some examples for more ideas:

- Secure Safety Solutions Wheelchair Seat Belt Alarm System : This is an adjustable belt that has a quick-release and non-restraint alarm activation. It has 85 dB of sound with an auto-reset feature. It is also tamper resistant and always on for safety. It can be attached to a wheelchair easily by using screws. It also does not have any breakable parts.

- ChairPro Seatbelt Alarm System : This is a nylon belt that has an easy-release buckle. An alarm sounds when the buckle is released, and it automatically resets when the buckle is secured. It is compatible with all standard wheelchairs.

Pressure Sensitive Floor Mat Alarms

Placing an alarmed floor mat next to the bed or chair of the patient can help alert a caregiver when the patient gets up and goes out of the bed or chair unexpectedly when he or she steps onto the mat. The weight triggers the pressure sensors on the mat to set off the alarm. It is a non-restrictive device that can help in keeping patients from wandering away from safety. However, some mat alarms might not be activated by patients who do not weigh that much. [ 6 ] Below are a few examples to help you choose:

- Smart Caregiver Cordless Floor Mat Pressure Pad : This is a cord-free floor alarm mat that does not have any alarming noise in the patient’s room. When it is stepped on, a signal will be sent to the alarm monitor, which has a radius of 150 to 300. The alarm has three volume levels and an on-and-off switch.

- Wander Prevention Alarm Monitor and Pressure Sensing Floor Mat : This is a wander prevention system that comes with a sensor pad monitor and a pull-string monitor. When the magnetic pull-string is pulled free of the monitor or when pressure is added to the floor mat, an alarm noise will sound to alert the caregiver.

Patient-Worn Alarms

There are also wearable patient alarms that come in different styles. Sometimes, one part of the alarm is attached to the bed, chair, or wheelchair while the other part is attached to the patient. When the patient wanders, the pull switch engages the alarm to signal to the caregiver that the patient has moved away from the chair, bed, or wheelchair. Patient-worn alarms can be clipped to the patient’s clothes or could be attached by a magnet. There are also some that feature a pull string. [ 6 ]

What’s great about patient-worn alarms is that they can be used at home or while outdoors. They also have simple designs. However, these alarms are sometimes removed by patients without triggering the alarm. That’s why choosing a high-quality one is essential. Below is an example to give you more idea of what they are:

- Safe-T Mate Magnetic Personal Alarm : This alarm is attached to the patient with a string that is clipped to the clothing. An alarm sounds when the cord is removed from the unit that is attached to the chair or bed.

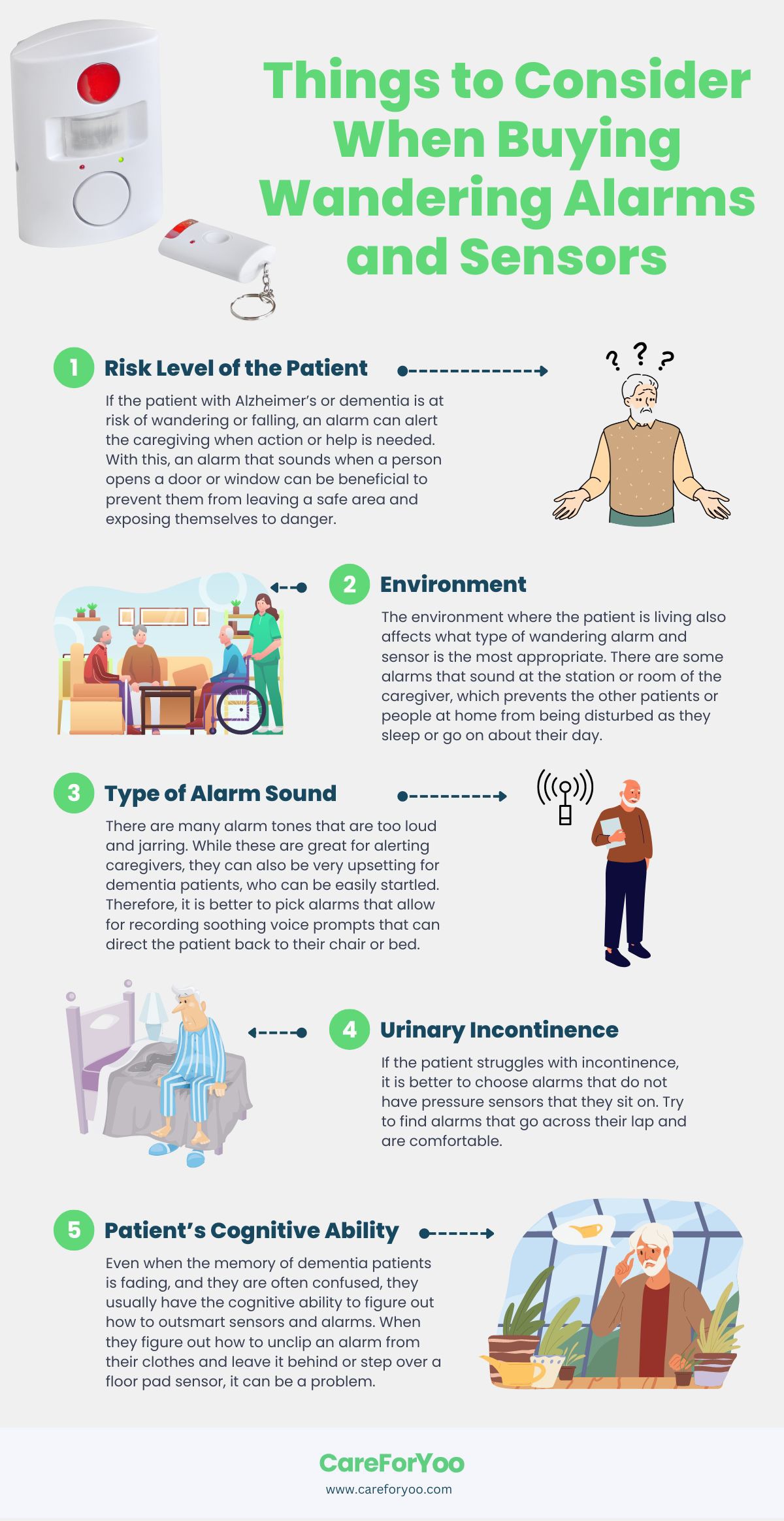

Things to Consider When Buying Wandering Alarms and Sensors

When choosing the type of wandering alarms and sensors to buy, the first and most important thing that you need to consider is the physical and mental condition of the patient. Aside from that, you also need to look into who they are sharing their living space with, the sound level needed to alert a caregiver without disturbing other people or scaring the patient, and how adept the patient is when it comes to disabling or getting around the alarms and sensors.

The following are the important things that you need to consider before you buy wandering alarms and sensors:

Risk Level of the Patient

If the patient with Alzheimer’s or dementia is at risk of wandering or falling, an alarm can alert the caregiving when action or help is needed. With this, an alarm that sounds when a person opens a door or window can be beneficial to prevent them from leaving a safe area and exposing themselves to danger. [ 6 ]

Environment

The environment where the patient is living also affects what type of wandering alarm and sensor is the most appropriate. There are some alarms that sound at the station or room of the caregiver, which prevents the other patients or people at home from being disturbed as they sleep or go on about their day.

Type of Alarm Sound

There are many alarm tones that are too loud and jarring. While these are great for alerting caregivers, they can also be very upsetting for dementia patients, who can be easily startled. Therefore, it is better to pick alarms that allow for recording soothing voice prompts that can direct the patient back to their chair or bed. [ 6 ]

Urinary Incontinence

If the patient struggles with incontinence, it is better to choose alarms that do not have pressure sensors that they sit on. Try to find alarms that go across their lap and are comfortable.

Patient’s Cognitive Ability

Even when the memory of dementia patients is fading, and they are often confused, they usually have the cognitive ability to figure out how to outsmart sensors and alarms. When they figure out how to unclip an alarm from their clothes and leave it behind or step over a floor pad sensor, it can be a problem. Therefore, it is also great to choose alarms and sensors that are out of reach or those that they can’t disable or turn off easily. [ 6 ]

Wandering alarms and sensors are beneficial to monitor patients with dementia, as well as those who are at risk of falling. It is also great that there are various options available in the market today so you can choose the right one that will match the condition of your loved one or patient.

In addition to using wandering alarms and sensors, other things that might help you in keeping your loved ones safe include using night lights throughout the home, camouflaging doors by painting them the same color as the walls, and not leaving the person alone for too long. We hope that this post helped you learn more about choosing the right wandering alarms and sensors.

[1] UPMC, E. (2022). Wandering tendencies in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia . UPMC. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://www.upmc.com/services/seniors/resources-for-caregivers/wandering-tendencies-patients-alzheimers-dementia

[2] Alzheimer’s Association, E. (2022). Wandering . Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering

[3] Heerema, E. (2022, April 23). Types of door alarms to improve safety for wandering in dementia . Verywell Health. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://www.verywellhealth.com/safety-in-dementia-door-alarms-98172

[4] Val-U-Care, E. (2021, September 6). The top 3 benefits of bed and chair exit alarm systems – val-U-care . Val. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://val-u-care.com/the-top-3-benefits-of-bed-and-chair-exit-alarm-systems/

[5] Technology Install Partners, E. (2022). 4 benefits of wandering management systems . Technology Install Partners. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://technologyinstallpartners.com/4-benefits-of-wandering-management-systems

[6] Price, OT, M. (2022). How to choose the best wandering alarm for dementia patients [updated for 2022] . Rehabmart.com. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://www.rehabmart.com/post/how-to-choose-the-best-patient-safety-alarm

Normal 0 false false false EN-US JA X-NONE /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Table Normal"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;} Normal 0 false false false EN-US JA X-NONE /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Table Normal"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;} SafeWander™ Monitors Those Who May Wander or Fall

You are not alone. More than 60% of the 47.5 million dementia patients wander. Wandering is also a concern for people with autism and other conditions. If not detected quickly, wandering can result in tragic incidents.

On the other hand, one in every three adults age 65 or older have risks of falling. Falls often happen when these individuals get up from their beds or chairs. A simple fall can have devastating consequences.

The world's first wearable sensor that alerts wandering on your mobile device, SafeWander™ gives you peace of mind.

Consisting of a tiny Button Sensor worn by your patient, a Gateway plugged near his/her bed, and a mobile device App, the SafeWander™ system sends a beeping alert to your mobile device as soon as the sensor detects your patient getting up.

The SafeWander™ System requires that you have an an Apple mobile device with iOS 8.0 or newer (iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch) or Android mobile device (Google Nexus 4/5/6, Samsung Galaxy S 4/5/6, Samsung Note 3, or Android 4.3 BLE devices) and strong WiFi in your home/facility.

- Português Br

- Journalist Pass

Alzheimer’s and dementia: Understand wandering and how to address it

Dana Sparks

Share this:

Wandering and becoming lost is common among people with Alzheimer's disease or other disorders causing dementia. This behavior can happen in the early stages of dementia — even if the person has never wandered in the past.

Understand wandering

If a person with dementia is returning from regular walks or drives later than usual or is forgetting how to get to familiar places, he or she may be wandering.

There are many reasons why a person who has dementia might wander, including:

- Stress or fear. The person with dementia might wander as a reaction to feeling nervous in a crowded area, such as a restaurant.

- Searching. He or she might get lost while searching for something or someone, such as past friends.

- Basic needs. He or she might be looking for a bathroom or food or want to go outdoors.

- Following past routines. He or she might try to go to work or buy groceries.

- Visual-spatial problems. He or she can get lost even in familiar places because dementia affects the parts of the brain important for visual guidance and navigation.

Also, the risk of wandering might be higher for men than women.

Prevent wandering

Wandering isn't necessarily harmful if it occurs in a safe and controlled environment. However, wandering can pose safety issues — especially in very hot and cold temperatures or if the person with dementia ends up in a secluded area.

To prevent unsafe wandering, identify the times of day that wandering might occur. Plan meaningful activities to keep the person with dementia better engaged. If the person is searching for a spouse or wants to "go home," avoid correcting him or her. Instead, consider ways to validate and explore the person's feelings. If the person feels abandoned or disoriented, provide reassurance that he or she is safe.

Also, make sure the person's basic needs are regularly met and consider avoiding busy or crowded places.

Take precautions

To keep your loved one safe:

- Provide supervision. Continuous supervision is ideal. Be sure that someone is home with the person at all times. Stay with the person when in a new or changed environment. Don't leave the person alone in a car.

- Install alarms and locks. Various devices can alert you that the person with dementia is on the move. You might place pressure-sensitive alarm mats at the door or at the person's bedside, put warning bells on doors, use childproof covers on doorknobs or install an alarm system that chimes when a door is opened. If the person tends to unlock doors, install sliding bolt locks out of his or her line of sight.

- Camouflage doors. Place removable curtains over doors. Cover doors with paint or wallpaper that matches the surrounding walls. Or place a scenic poster on the door or a sign that says "Stop" or "Do not enter."

- Keep keys out of sight. If the person with dementia is no longer driving, hide the car keys. Also, keep out of sight shoes, coats, hats and other items that might be associated with leaving home.

Ensure a safe return

Wanderers who get lost can be difficult to find because they often react unpredictably. For example, they might not call for help or respond to searchers' calls. Once found, wanderers might not remember their names or where they live.

If you are caring for someone who might wander, inform the local police, your neighbors and other close contacts. Compile a list of emergency phone numbers in case you can't find the person with dementia. Keep on hand a recent photo or video of the person, his or her medical information, and a list of places that he or she might wander to, such as previous homes or places of work.

Have the person carry an identification card or wear a medical bracelet, and place labels in the person's garments. Also, consider enrolling in the MedicAlert and Alzheimer's Association safe-return program. For a fee, participants receive an identification bracelet, necklace or clothing tags and access to 24-hour support in case of emergency. You also might have your loved one wear a GPS or other tracking device.

If the person with dementia wanders, search the immediate area for no more than 15 minutes and then contact local authorities and the safe-return program — if you've enrolled. The sooner you seek help, the sooner the person is likely to be found.

This article is written by Mayo Clinic Staff . Find more health and medical information on mayoclinic.org .

- Answers to common questions about whether vaccines are safe, effective and necessary Consumer Health: Treating and living with HIV and AIDS

Related Articles

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Door Alarms for Wandering in Alzheimer's and Dementia

SilviaJansen / Getty Images

If your loved one with Alzheimer's disease or a different type of dementia wanders and attempts to leave your home or facility, one option to increase their safety is to place alarms on the doors. You can also try different locking mechanisms such as a latch up high, but the concern with that strategy is that in case of a fire, the person may not be able to escape safely out of the house.

An alarm can allow the person to attempt exiting through the door but will also alert you to her need for assistance. Alarms can offer you a little support and reassurance in your efforts to ensure your loved one's safety so that, rather than feel that you have to constantly check on her, you know that the alarm will sound if she suddenly wakes and needs assistance.

Protect individuals from elopement and wandering: Whether people with dementia intentionally attempt lopement or are simply wandering around to locate a door, those at risk for exiting without the needed supervision may benefit from a door alarm on the exterior doors.

Alerts others for assistance: Door alarms can also be used on the bathroom door. They can be placed in such a way that they'll sound when the door is opened, letting you know that your loved one requires assistance in the bathroom.

String alarm: A string alarm can be placed high up on the door frame with the string placed across the door opening. If the door opens, it will cause the string, which is held in place by a magnet, to detach from the alarm, causing it to sound. The alarm will stop sounding once the magnet is reattached.

Passive InfraRed (PIR) alarms: A PIR alarm can be utilized across a door opening so that if the plane across the door is broken, the alarm will sound and alert you to your loved one's need for assistance.

Magnetic door alarms: Magnetic door alarms have two parts that are connected magnetically. One part is attached to the door frame right at the edge next to the door and the other part is attached to the door right next to the frame. The alarm sounds when the two parts are no longer connected by the magnet.

Floor sensor alarms: Floor sensor alarms have a sensor pad on the floor and a magnetic lock on the door. They can be preset to different settings, some of which will alarm immediately and other settings that allow a person to exit out the door and return just a short time later before sounding.

Remote sounding alarms: Some alarms are designed so that they sound away from the person who is trying to get out the door. You might place the sounding device of the alarm near you so that it doesn't startle the person with dementia but will alert you to their need for assistance.

Keypad locks: Another option if you have doors in your house that you don't want your loved one to open, you can simply lock them or have a keypad lock installed on those doors. The keypad locks will unlock once you enter the correct number code in the keypad. Keypad locks can connected be to the smoke or fire alarm system so that they will unlock in case of a fire.

GPS alert systems: There are several GPS devices that can assist with keeping your loved one safe. GPS trackers can be used in a variety of ways, such as in shoes. watches and bracelets. You can set up perimeters for when you want to be alerted (such as a doorway) or you can continuously track the person on an app on your phone. These types of systems allow you to have a flexible level of monitoring, depending on your loved one's needs.

A Word From Verywell

As caregivers , one of our worst fears may be that our loved one with dementia will accidentally get lost or purposely leave a house or facility, not be able to find her way back home and then become endangered. Utilizing strategies to prevent wandering, such as understanding the common causes and using door alarms, can hopefully reduce this risk significantly and provide a little more peace of mind.

National Institute on Aging. Home Safety Checklist for Alzheimer's Disease.

Agrawal AK, Gowda M, Achary U, Gowda GS, Harbishettar V. Approach to management of wandering in dementia: ethical and legal issue. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine . 2021;43(5_suppl):S53-S59. doi: 10.1177/02537176211030979

Au-Yeung WT, Miller L, Beattie Z, Kaye J. Passive infrared motion sensors improved the detection accuracy of nocturnal agitation. Innovation in Aging . 2021;5(Supplement_1):955-955. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab046.3417

Hall A, Wilson CB, Stanmore E, Todd C. Implementing monitoring technologies in care homes for people with dementia: A qualitative exploration using Normalization Process Theory. International Journal of Nursing Studies . 2017;72:60-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.04.008

Megges H, Freiesleben SD, Rösch C, Knoll N, Wessel L, Peters O. User experience and clinical effectiveness with two wearable global positioning system devices in home dementia care. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions . 2018;4(1):636-644. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.10.002

By Esther Heerema, MSW Esther Heerema, MSW, shares practical tips gained from working with hundreds of people whose lives are touched by Alzheimer's disease and other kinds of dementia.

- Sign In

Best Dementia Wandering Products

Caring for people with dementia can be a challenge, especially if that person is prone to wandering. Whether they end up out in the world, or are simply roaming around the house, they're at serious risk of falls or other accidents. In both professional and home care environments, preventative measures are essential, and help avoid stressful and frightening situations.

In this Best Dementia Wandering Products guide, we go over some brilliant dementia care items that our customers love. Each product is designed to help avoid specific wandering scenarios, so you can find the most appropriate items for you.

What Does This Guide Cover?

- Best Dementia Chair Pressure Mat

- Best Dementia Bed Pressure Mat

- Best Dementia Floor Pressure Mat

Best Dementia GPS Tracker

Best dementia alarm for doors and windows, best dementia motion sensor, best dementia crash mat, best dementia hip protector, looking for a full fall and wandering system, what else can you do to help prevent wandering, best dementia chair pressure mat.

Winner: Wireless Care Alarm Kit with Chair Leaving Sensor Mat

Why We Love It...

✔ Lets carers know immediately if a patient leaves or falls out of chair ✔ Small sensor pad fits comfortably and seamlessly on most chairs ✔ Receiver is wireless so a carer can always carry it with them

Not The Best For...

✘ Monitoring a larger surface area like a bed ( See our solution )

Customer Verdict: "A fantastic product. Very quick and easy to set up and it has been a great help in keeping my 95 year old father safe. His carer can now leave him sitting in his chair while she does jobs and know instantly if he has stood up. It has saved him from falling many times already and we have only had it a couple of weeks." Stephanie ★★★★★

Best Dementia Bed Pressure Mat

Winner: Nutrix Wireless Care Alarm Kit with Large Bed Leaving Sensor Mat

✔ Lets carers know immediately if a patient leaves or falls out of bed ✔ Design fits under patients back and can be used in nearly any bed ✔ Receiver is wireless with wristband so a carer can always carry it with them

✘ Protecting a patient from harm if they do fall ( See our solution )

Customer Verdict: "This sensor mat is really Brilliant. My mother gets out of bed during the night and this alarm let's me get to her before the possible of her having a fall." David ★★★★★

Best Dementia Floor Pressure Mat

Winner: Floor Pressure Mat Wander Alarm With Pager and Transmitter

✔ Huge 120m range so can be placed in most beneficial position in home ✔ Can be hidden under a rug or carpet for more discrete home care ✔ Wireless receiver is fantastic for busy, professional home care settings

✘ Keeping track of patients if they don't trip the alarm ( See our solution )

Customer Verdict: "Purchased this for my husband who has dementia and wonders a lot in the night. It alerts me when he is out if bed so I can reassure him and tuck him in again. Simple to set up and can hear it just on vibration or vibration and low level alarm bearing in mind I am quite deaf." Patricia ★★★★★

Winner: Medpage GPS Location Tracker Watch Phone with Fall Detection

✔ SOS fall alarm has precise mapping location so patient for safety ✔ Blood pressure and heart rate monitoring, plus medication reminders ✔ Battery lasts for 7 - 10 days to so it won't lose charge in an emergency

✘ Physical protection in event of fall ( See our solution )

Editor's Verdict: As well as being a tracker and SOS fall alarm, this Medpage watch is also a phone. This allows carers or loved ones to call the wearer in the event of wandering, to talk to them or someone that has found them. It's also a versatile care device with blood pressure and heart rate monitoring, along medication reminders

Winner: Wireless Door and Window Security Alarm with Radio Pager Kit

✔ Fixed next to doors or windows to notify when they've been opened ✔ Three notification settings: high volume, low volume and vibration ✔ 100m transmission range and a massive 6 months of battery life

✘ Preventing accidents within a room ( See our solution )

Customer Verdict: "Peace of Mind - This product is exactly what I needed. My father has dementia and can become confused at night. I now know instantly if he leaves his bedroom...so I can get a good nights sleep". Lorraine ★★★★★

Winner: Alerta Detect Motion Sensor and Wall Point Wireless Receiver

✔ Infrared PIR sensor detects body movement without physical contact ✔ Allows for greater patient freedom than floor pressure mats ✔ Powered by either mains or battery and connects to nurse call system

✘ A higher level of precaution ( See our solution )

Editor's Verdict: Offering an alternative to pressure mats, this infrared sensor detects patient movement without them having to physically trigger it. It offers greater freedom than a mat as it allows patients to get out of bed or move around the room without triggering an alarm, as long as they don't cross the sensor beam threshold.

Reducing Injury In Case of a Fall

Winner: Harvest High Density Foam Crash Mat

✔ High density foam ensures a cushioned landing in case of bed falls ✔ Waterproof and vapour-permeable cover ideal for incontinent patients ✔ Gives both patients and carers greater peace of mind when unsupervised

✘ Alerting carers before a patient falls ( See our solution )

Editor's Verdict: Ideally, if you use a bed pressure mat, a patient won't fall out of bed. However, in the time it takes for a carer to reach a patient, accidents can happen and it's important to be prepared. This high density foam mat offers fantastic cushioning to help avoid falls, which can be extremely dangerous for elderly patients.

Winner: Safehip AirX Hip Pad Hip Protector Underwear

✔ Wearable fall protection, not limited by location like a crash mat ✔ Breathable and elastane build offers long-lasting comfort ✔ Designed to be discreet and fit easily under regular clothes

✘ Protecting other parts of the body in case of falls ( See our solution )

Editor's Verdict: Hip injuries can be particularly debilitating for elderly people, especially those with dementia who might find rehab tricky. These underwear offer wearable hip protection that dementia sufferers can take with them wherever they go.

The mats, sensors and protective equipment above are great, especially for smaller scale, or home care environments. But if you're looking after multiple patients with dementia or other memory issues, you might want to consider a more comprehensive system like the Alerta Wireless Full Fall and Wander Alarm System .

✔ Incredibly comprehensive system for maximum patient safety ✔ Wireless receiver links to all five transmitters at the same time ✔ Includes 3 pressure sensors, a electric crash mat and a call button

✘ Smaller rooms or spaces ( See our solution )

Editor's Verdict: Perfect for professional care environments, or for extra-safe home care, this six-item bundle hugely reduces the chances of dementia wandering accidents. The receiver monitors all five sensors at the same time and can differentiate which one has been activated, so a carer knows exactly where they are needed.

To help prevent the worst case scenario, here are some simple steps you can take:

- Create a Routine - Having a concrete daily plan can help to prevent the restlessness that often leads to wandering. If your loved one is occupied with getting through their day, the risk of distraction can be greatly reduced.

- Ensure Needs are Met - Wandering is often triggered by a need to find water, food or go to the bathroom. If you make it safe and easy for your loved one to achieve these simple goals, it can go a long way to keeping them happy and relaxed.

- Have an Action Plan - If wandering does occur, make sure you're prepared. Ensure your loved one has an ID on them at all times, keep a recent photo and updated medical information on hand, and contact emergency services as soon as possible.

Need More Help Selecting A Dementia Wandering Product?

The alarms and other products we've talked about are some of our favourites, tried and trusted by our customers, but we understand everyone's care situation can be different. If you still haven't found what you're looking for, why not have a look at the rest of our Anti-Wander Alarm range.

Whether you're looking to make a professional care home safer, or just give a loved one a bit of peace mind, we're sure we have something for you!

Do you have any questions about our products to prevent dementia wandering, or something to add? Share your thoughts below or contact us on Facebook and Twitter .

Tags: Alarms and Alerts , Care Support , Dementia , Wandering

My mother has dementia and we need to get a floor mat as she is falling. Do you supply to ireland

Hi Marie, I'm sorry to hear about your mother, hopefully something like the Fall Alarm with Voice Alert mentioned above will be able to help. To answer your question, we do deliver to Ireland. This will usually incur an extra £10 delivery fee. If there's anything else you need, don't hesitate to ask and we'll get back to you as soon as we can. Kind regards, Eugene at Health and Care

- Managing Wandering Behavior in Dementia Seniors

Managing Wandering Behavior in Dementia Seniors: Memory Care Community Solutions

By Publisher | Published April 12, 2023 | Last updated April 12, 2023

Wandering behavior in seniors with dementia can be both perplexing and concerning for their loved ones and caregivers. With a lack of understanding of their environment and a diminished ability to express their needs, seniors with dementia may wander aimlessly, attempting to fulfill a basic need or to escape perceived dangers.

Memory care communities are specifically designed to provide safe and supportive living spaces that address wandering behavior while preserving the dignity and individuality of their residents. This article will explain the reasons behind wandering behavior in seniors with dementia . We will also explore the various strategies memory care communities implement to create secure, nurturing environments.

Understanding Wandering Behavior in Seniors with Dementia

Causes of wandering behavior.

Wandering can stem from multiple factors — physical, emotional, and environmental — which may include:

- Unmet needs : Hunger, thirst, or the need to use the bathroom may trigger wandering as the individual searches for a way to satisfy these basic requirements.

- Disorientation : Memory loss and confusion can cause seniors to feel lost, prompting them to wander in search of familiar surroundings.

- Boredom or excess energy : Idleness or restlessness may lead to wandering as a means to expend energy or find cognitive stimulation.

- Past routines : The ingrained desire to follow previously established routines or habits may spur wandering behavior.

The Risks of Wandering

Unmonitored wandering can lead to various hazards, including:

- Falls or injuries

- Accidents or getting lost outdoors

- Exposure to harsh weather conditions

- Fear, anxiety, and emotional distress for the individual and their family

Memory Care Communities: Creating Safe Living Spaces for Seniors with Dementia

Memory care communities strive to provide a comprehensive support system that addresses the unique needs and challenges of individuals with dementia. By incorporating specialized staff training, state-of-the-art security measures, and evidence-based design elements, these communities create safe and engaging living spaces that minimize wandering behavior and its associated risks.

Staff Education and Training

Expertly trained staff is crucial in managing wandering behavior in seniors with dementia. Memory care communities prioritize ongoing education and skill development, ensuring staff members:

- Understand the possible triggers for wandering.

- Recognize signs of agitation or anxiety that may precede wandering behavior.

- Employ effective communication techniques to guide residents calmly and compassionately.

- Respond quickly and effectively in case of emergencies.

Security and Monitoring Systems

Preventing incidents associated with wandering requires comprehensive security measures. Implementing these measures in memory care communities can include:

- Secure, monitored entrances and exits to prevent unauthorized departures and wandering outdoors

- Location tracking technologies to monitor resident movement within the community

- Video surveillance systems to maintain a visual record of resident activity

- Alarmed doors and windows to signal potential wandering attempts

Therapeutic Design Elements

Architectural and design features can significantly minimize wandering behavior, creating safe and easily navigable environments for seniors with dementia. Key design elements in memory care communities can comprise:

- Circular or looped walking paths that allow residents to wander with a purpose and prevent agitation from dead-end corridors

- Visual cues and signage to assist residents in locating restrooms, dining areas, and other common spaces

- Private and secure outdoor spaces where residents can explore safely and interact with nature

- Contrasting colors and patterns to help residents distinguish between various surfaces and objects, reducing potential confusion

Individualized Care Plans and Engaging Activities

Focusing on personalized care and tailored activities is crucial in addressing the root causes of wandering behavior. Memory care communities strive to:

- Develop comprehensive care plans that address individual needs, preferences, and personal histories

- Offer a variety of engaging activities and programs that meet residents' cognitive and physical abilities

- Monitor residents' daily routines and adapt care plans as needed , ensuring continued satisfaction of basic needs and desires

What is wandering behavior in seniors with dementia?

Wandering behavior refers to aimless movement or walking with no apparent goal, often indicative of confusion and disorientation resulting from dementia.

How do memory care communities address wandering behavior?

Memory care communities utilize specialized staff training, comprehensive security measures, therapeutic design elements, and personalized care plans to minimize wandering behavior and ensure the safety and well-being of their residents.

What are some possible causes of wandering behavior in seniors with dementia?

Wandering behavior can stem from unmet needs, disorientation, boredom, excess energy, or a desire to follow past routines.

How can I help prevent wandering behavior in a loved one with dementia?

Providing a safe and structured environment, addressing basic needs, offering engaging activities that match their cognitive abilities, and maintaining familiar routines can help prevent wandering behavior in seniors with dementia.

Addressing wandering behavior in seniors with dementia is an essential aspect of providing comprehensive and compassionate care. Memory care communities focus on creating safe living spaces that foster autonomy, self-esteem, and dignity. Through uniquely tailored strategies, memory care communities continue to enhance their residents' safety and overall quality of life, offering peace of mind to families, caregivers, and their loved ones living with dementia.

Related Articles

- Aging in Place

- Assisted Living vs. Nursing Home Care

- Depression: What Does it Look Like and When to Seek Help

- Memory Care: How to Find the Right One

- Memory Help — How to Boost Your Brain

- Senior Home Care

- Sundowners Syndrome: Facts and Care Tips

- What is Assisted Living?

- What is Dementia?

- What to Expect From the Aging Process

- When You Need to Place Your Parent in a Nursing Home

GreatSeniorLiving.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and its partner websites.

© 2017 - 2024 GreatSeniorLiving.com

We may earn money when you buy through our links.

Home | Senior Safety | Best Door Chimes for Seniors with Dementia

Best Door Chimes for Seniors with Dementia

SafeWise experts have years of firsthand experience testing the products we recommend. Learn how we test and review .

Door chimes alert in-home caregivers when seniors leave the house—which could be dangerous for people with Alzheimer’s and dementia.

These door chimes for seniors differ from traditional home security door sensors because they don’t send alerts to a monitoring center or app, nor do they set off a loud siren meant to scare people. Instead, the in-home caregiver keeps the chime box in their pocket or a central location for instant alerts.

Our favorite door chime for seniors is the SMPL Alerts 4-in-1 kit because the caregiver can carry around its alarm pager, and there’s a motion sensor and wearable call button to round out the package.

Best door chimes for seniors

- SMPL Alerts : Best overall

- YoLink : Best for multiple doors

- Stechro : Best for budgets

- EverNary : Best motion sensor

- Alerta Patch : Best wearable

- How we reviewed

Compare the best door chimes for seniors with dementia

*Amazon.com price as of post date. Read full disclaimer .

Best senior door chimes reviews

1. smpl alerts: best overall.

*Amazon.com price as of post date. Read full disclaimer .

The SMPL Alert 4-in-1 Kit covers all the bases for ensuring your loved one doesn’t wander out the door. The motion sensor can be placed near the door for an early warning alarm, while the door sensor lets you know when the door opens. This kit includes a portable pager and a wearable help button.

You can also use the motion sensor from this kit in another area of the home, such as near the senior’s bed for a fall alert.

The pager includes a belt clip and works within 250 feet of the sensors. And the pager sounds an alarm while also vibrating and flashing.

We love that this system also includes a help button seniors can use to call for help. It only works if they’re still in range of the pager, though, so it won’t work if they’ve already wandered too far.

2. YoLink: Best for multiple doors

The YoLink Smart Home Starter Kit includes four door sensors and a base station. Its station announces which door opened, which is especially useful in a larger home since caregivers will know which exit to check.

The base station works within 1000 feet of each sensor and uses a special technology called LoRa to improve its range over multiple floors. YoLink can also tell you when a door is ajar.

3. Stechro Wireless Door Chime: Best for budgets

The Stechro Wireless Door Chime is a budget-friendly option with one flaw: the chime must stay plugged in. But with five volume levels, it should be loud enough for caregivers to hear, especially when placed in a central location.

You can get kits with up to three Stechro Door chimes to cover all exits in the home. Up to 62 ringtones are available, which helps prevent the chime sound from scaring seniors who may already feel confused.

The Stechro Wireless Door Chime has the second-longest range on our list at 600 feet, making it ideal for larger homes.

4. EverNary: Best motion sensor

The EverNary Wireless Caregiver Pager connects to a motion sensor instead of a door chime. This connection makes it ideal for an open floor-plan space to alert the caregiver when the senior wanders close to the door.

We especially like the adjustability of the EverNary motion sensor, allowing you to set it up just right for fewer false alarms.

Be sure to select the Portable Pager option for a chime caregivers can take with them. It has a limited range of just 260 feet in an open area. We recommend testing how far the pager works in your home since walls and other obstructions can lower the range.

5. Alerta Patch: Best proximity wearable

The Alerta Patch offers a unique solution for Alzheimer’s and dementia wandering prevention. A wearable sensor applies to the skin on the person’s upper back for one month. The sensor pairs to a “Wedge,” which looks like a remote control. An alarm goes off if the sensor travels farther than 65 to 95 feet away from the Wedge.

This option is excellent for seniors who have tried to remove other wearable devices or may be a flight risk when attending appointments or other activities away from home.

Unfortunately, there’s no tracking technology in the patch. If your loved one disappears, the Alerta Patch can’t help you find them. Check out our recommended GPS trackers for Alzheimer’s and dementia instead if you need tracking.

We think the best door chime for seniors is the SMPL Alert . It’s a basic bundle of senior monitoring products for in-home caregivers. It also has a portable pager that offers three alerts. You can stick with the starter kit or buy additional SMPL sensors to cover every exit.

Are there other types of wandering alerts for seniors?

Yes, there are other types of wandering alerts for seniors. For instance, you can use pressure-sensitive floor mats as a door alert instead of motion or door sensors.

Can I use a video doorbell as a wandering sensor?

Yes, video doorbells can be positioned inside the door and used as a more sophisticated motion sensor. Be sure to get one with a motion-activated chime so that the in-home caregiver can hear when it goes off. However, we like portable pagers made especially for seniors who wander because the chime goes off continuously.

How we reviewed door chimes for seniors

We looked for door chimes offering a connection to a portable pager or had another unique alert system for in-home caregivers. We also based our top recommendations on the signal range and the ability to add more sensors if needed. Learn more on our methodology page.

Related articles

- Best Medical Alert Systems

- Room-by-Room Guide to Senior Safety

- Best Safety Devices for Seniors

*Product prices and availability are accurate as of post date and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on Amazon at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product. Safewise.com utilizes paid Amazon links.

Certain content that appears on this site comes from Amazon. This content is provided “as is” and is subject to change or removal at any time.

Recent Articles

About Contact Press News Deals

Home Security Internet Security Home Safety Family Safety Senior Safety

Car Safety Smart Home Emergency Prep Pet Safety Personal Safety

Subscribe to SafeWise for updates on safety news, product releases, and deals!

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy | How We Rank and Review |

*SafeWise has conducted impartial research to recommend products. This is not a guarantee. Each individual’s unique needs should be considered when deciding on chosen products.

©2024 SafeWise. All rights reserved.

Sweet Moment Senior Dog With Dementia Forgets He's Already Greeted Owner

S eeing our four-legged best friends age and deteriorate is one of the hardest experiences to go through, because after so many years of love, they need us more than ever.

That's exactly what Dennis Gerard, 60, is facing with his rescue dog Piper, who turned 17 years old last year. The senior dog is now blind, deaf, and suffers from dementia. Gerard told Newsweek that he's "slowly getting worse," which is devastating to witness.

However, age isn't going to stop Piper from adhering to his usual routine, so he still loves to greet his owner with a kiss and a happy dance when he returns home. But Gerard, from Jacksonville, Florida, recently captured the moment Piper evidently forgot that his owner had already come back home, and he continued to wait in the hallway for him and got stuck as he couldn't see where he was going.

"I came home from work and Piper was waiting in the foyer by the back door for me. Once I entered and he smelled me, then he performed his usual ritual of kissing me and dancing and welcoming me home," Gerard said.

"A half-hour later, I was making a sandwich and watched him wander into the foyer and position himself for me to come through the door again. He was having a bad day and he forgot that I'd just come home. He was waiting for me again, it was so sad."

Gerard rescued Piper when he was 2 years old, and they've shared countless happy memories in the 15 years since. But it's been heart-breaking for the owner to watch the pooch's health slowly decline, especially this moment, which was the first time Piper had forgotten that his owner was already home.

Dog dementia is not uncommon in senior pooches, and it can also be referred to as canine dysfunction syndrome (CDS). One study revealed that signs of dog dementia increased to 68 percent in dogs aged over 15 years.

The American Kennel Club states that symptoms usually include disorientation, house soiling, a change in sleep patterns, and a change in activity levels. Owners may also see a change in their relationships, as a once independent dog may become clingier for example. Senior dogs may also develop new fears or vocalize more, which can be attributed to increased nervousness.

Sundowner syndrome is another sign of cognitive deterioration, causing a dog to sleep more during the day and then become restless at night, or they may pace or bark for no apparent reason during the night instead of sleeping.

Sadly, there is no cure for dog dementia or CDS, but the AKC recommends that owners help manage the symptoms, provide the dog with a schedule they can follow, and give them plenty of mental enrichment.

How Did Social Media React?

Living with a senior dog isn't easy, but Gerard documents his life with Piper on social media (@dennis.gerard on TikTok and @pipersdad3 on Instagram ), to show that an old dog is no less important or loving. The sweet clip of Piper getting "stuck while sundowning" has been viewed over 2.4 million times and gained more than 186,900 likes on TikTok in just a matter of days.

"People can really connect emotionally with posts like this," Gerard told Newsweek after the video went viral. "I've had thousands of comments, and every one of them is positive and uplifting, people are sharing their similar experiences with their dogs both past and present.

"We live in a time of great division, but senior dogs like Piper can unite us around a common platform of love, empathy, and compassion. This is one of those things that's sad and cute at the same time, I love it and I hate it. I am his whole world, and it does bring me great joy seeing how much he loves me."

Despite his age, it's not just Gerard who loves Piper so much as the senior dog has earned plenty of fans through social media. And one thing is for certain, they can all agree that "Piper is a good boy" no matter how old he gets.

Many TikTok users were deeply moved by the video, and it's already gained over 5,300 comments. One person wrote: "Why does any of this have to happen to our babies."

Another TikTok user responded: "We are the keepers of their souls until it's time to cross the rainbow bridge."

A third comment reads: "So beautiful and sad at the same time."

Do you have any heartwarming videos or pictures of your pet you want to share? We want to see the best ones! Send them in to [email protected] and they could appear on our site.

Start your unlimited Newsweek trial

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sensors (Basel)

Intelligent Sensing Technologies for the Diagnosis, Monitoring and Therapy of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review

Associated data.

Not applicable.