- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

'It's catastrophic': Fiji's colossal tourism sector devastated by coronavirus

Tourism employs about 150,000 people in the Pacific nation, but travel restrictions mean the work and the money are drying up

On a typical evening Suva’s Holiday Inn is packed with guests from all over the world. But tonight, the dining room of the hotel, one of the most popular in Fiji’s capital, which normally buzzes with the dinner rush, stands empty,

Looking lost amid the empty tables is waiter Samuela Yavala.

“I’ve been in the industry for a good 19 years and I have never seen anything like this,” he says.

Before the coronavirus crisis, Yavala could make FJ$300 (£106) a week after overtime and tips, which is relatively high for country with a minimum wage of FJ$2.68 an hour for unskilled workers. Since the pandemic, his hours have been reduced and his salary halved and Yavala wonders how he will support his elderly parents. His biggest fear is being laid off completely.

“I don’t know what I’ll do,” he says. A similar scene is being played out across Fiji’s tourism hotspots as the coronavirus bites into the Pacific island’s most important industry. As jobs are slashed and incomes dry up, people like Yavala face a desperate future.

Fiji has so far recorded 16 confirmed Covid-19 cases with no deaths so far. The government responded swiftly and firmly to the outbreak, closing the country’s main airport in Nadi on 25 March, six days after Fiji announced its first confirmed case, which was brought into the country by a flight attendant.

Since then, the entire country has to abide by a curfew from 8pm to 5am and police and the military are out enforcing the coronavirus laws.

The country is braced for a deadly outbreak that would quickly stretch its health system to breaking point. But even if the worst-case health scenario is avoided, a devastating economic impact looks unavoidable .

Tourism contributes nearly 40% to Fiji’s gross domestic product – about FJ$2bn (AU$1.4bn) – and directly or indirectly employs over 150,000 people in various industries. Last year, Fiji had more tourists coming into the country (894,000) than residents living in it (roughly 880,000). The bulk of its tourists come from nearby Australia (41%) and New Zealand (23%), which like many countries around the world have banned international travel.

Fiji Airways, the country’s national airline, has grounded 95% of flights amid travel restrictions and border closures around the world and the Fiji Hotel and Tourism Association (FHTA) says a staggering 279 hotels and resorts have closed since the outbreak reached Fiji, causing more than 25,000 to lose their jobs, particularly in the western part of the country’s main island, the hub of the industry and the gateway to many resort islands.

“This will be catastrophic,” says Tony Whitton, managing director of Rosie Holidays and Ahura Resorts. The Rosie Group plans to reduce its workforce from about 600 workers to 40 essential staff in the coming weeks.

“My view is that it will take one year at least – so until the end of 2021 – just for the industry to recover and we won’t see growth until at least 2022,” he said, adding that any recovery in the industry will depend on when source markets such as Australia and New Zealand open their borders again.

The knock-on effect of these job cuts will be enormous. Many of those employed in the tourism sector support dependents in a country where the wages are low, cost of living is high, and government support is minimal.

The wages Joape Anare earned while working at the Tanoa Group of Hotels in Nadi supported his parents and put his two sisters through school.

He was laid off due to the coronavirus crisis and has been has forced to move back to his village on Beqa Island, located about 45km south of Suva, to survive from subsistence farming.

“Handing in my uniform before leaving was really hard and indeed an emotional experience. My work was my life. I don’t know whether I will be returning to this field again,” he said.

Fiji’s minister of economy and attorney-general Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum announced a FJ$1bn economic stimulus budget in late March to assist businesses and workers in the current climate, which allows some workers to access up to FJ$1,000 from their superannuation funds, with government topping up payments for ineligible applicants.

But Nigel Skeggs, director of The Rhum-Ba, a restaurant bar on Denarau Island in Nadi, has urged the government to reduce taxes to help businesses stay open, saying Fiji’s tourism operators had been struggling for some time with the burden of keeping Fiji’s economy afloat.

“Our top-heavy tax system has taken all domestic liquidity away and left operators with minimal profit and significantly reduced cashflows - for most small businesses this means little to no savings,” he said.

The Reserve Bank of Fiji expects the country’s economy to slide into a recession in 2020 after nearly 10 consecutive years of growth.

According to the World Bank’s recently released East, Asia and the Pacific economic update, the severity of the contraction will depend on how long the Covid-19 crisis lasts.

Professor Stephen Pratt, head of the tourism school at the University of the South Pacific says that the crisis was an opportunity for operators to reimagine what Fiji’s industry will resemble in a post-coronavirus world.

“It’s a bit of a paradigm shift and it’s a chance for the industry and academics to say what sort of tourism do we want going forward,” he said.

“I think there will be some fundamental changes in not just Fiji but the source markets as well. International politics are involved so there might be things like safe countries or blocs of countries that have their own agreements for travellers.

“Tourism is a people to people business and fundamentally goes against social distancing,” he said. “We are watching closely.”

- The Pacific project

- Coronavirus

- Asia Pacific

- Pacific islands

- Infectious diseases

Most viewed

- Disclosures

- Insights & Reports

Owned by 186 member countries and consistently rated AAA/Aaa. IFC aims to achieve our mission of promoting development by providing debt and equity to the private sector, through a range of benchmark and bespoke products.

- Governments

- Apply for Financing

- IFC Careers

- General Inquiries

The Future of Fiji’s Tourism Industry Is Green

Under turquoise seas a unique cornucopia teeming with marine life awaits those lucky enough to holiday in South Pacific nation Fiji.

Visitors here are welcomed with open arms. Tourism is vital to the lives and livelihoods of everyone in Fiji. Now rebounding strongly after the pandemic forced a virtual shutdown, Fiji’s tourism industry faces a critical challenge: To help drive widespread sustainable prosperity it must both leverage and protect its unique environment, while equipping itself to withstand the worsening ravages of climate change.

“The only way we can usher a new phase of tourism development is if sustainability is at the heart of it – for the sake of our future generations,” said Fiji’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Tourism and Civil Aviation, Hon. Viliame Gavoka.

Tourism-reliant economies like Fiji were among the world’s hardest hit by the pandemic. In a nation of more than 900,000 people, over 200,000 Fijians lost their jobs. The economic impacts were stark: In 2020, Fiji’s real gross domestic product (GDP) growth plummeted to a decline of 17 percent .

Before the pandemic tourism operators Maureen and Rodney Simpson had a thriving business employing 10 people in Savusavu, a resort on Fiji’s second biggest island Vanua Levu. When international borders closed life immediately became a lot more precarious for them and their workers.

“We had zero income,” Maureen Simpson said. “When tourism re-opened, we renamed ourselves from Dive for Life to Dive Savusavu, basically to advertise Savusavu.

Reopening and the return of tourists has helped drive a much-needed economic recovery in Fiji. GDP growth is estimated at 15.1 percent in 2022 and to be 5.4 percent in 2023 . The Fiji Bureau of Statistics reported that Fiji’s visitor arrivals for December 2022 surpassed pre-Covid levels with 75,580 visitors landing in Fiji or 102 percent of 2019.

Now, tourists are returning in good numbers, staying longer, and spending more per day compared to 2019 according to early post-COVID findings of the International Visitors’ Survey, which IFC also supports. And when people come to Fiji for a holiday, they like to return: the healthy bounce is backed by repeat visitors who are half of all arrivals.

Reefs and Business Come Back To Life

In Savusavu it’s 10 in the morning and the floating bures dotting the crystal waters in front of the picturesque Koro Sun Resort are still locked up.

It might seem quiet, but happily, the tourists are back. The latest arrivals are resting after travelling over 16,000 kilometers and 30 hours from the United Kingdom to experience unique diving in Fiji’s “soft coral capital”. Vanua Levu is known for stunning beaches and waters carpeted with jaw-dropping arrays of coral and sea life. Tourists travel there from all over the world to snorkel and dive.

Close by, the Simpsons are busy directing their workers to check oxygen tanks, dive equipment and snorkeling gear. Like most other tourism operators, they have been busy since borders reopened in 2021.

“We noticed during these two years when we were closed, our reefs have really come back to life. We also have turtles, hammerhead sharks and even whales around the dive spots – we respect them, and they respect us. And this has been the highlight of our diving,” Maureen Simpson said.

Promise of a Sustainable Path

Vanua Levu is part of a long-term vision in Fiji to develop a more diversified and sustainable tourism sector.

IFC is working with people and groups from across the industry to assist. This includes enabling sustainable, green and climate resilient investments and helping the Ministry of Tourism and Civil Aviation (MCTA) to develop standards for tourism businesses. IFC is also supporting the MTCA to develop the National Sustainable Tourism Framework. This framework will provide a blueprint and strategy for an inclusive, resilient, and sustainable tourism industry.

It comes amid a sharp focus on the benefits sustainable development has to offer. Targeting $3 billion Fijian dollars in visitor expenditure by next year, Tourism Fiji’s Corporate Plan for 2022-2024 urges “a strong focus on conserving the special environment that attracts our visitors.”

Fiji Hotel and Tourism Association CEO, Fantasha Lockington said the renewed focus on sustainability being driven at national level represented a positive shift as “it was previously delivered on far smaller scales by individual businesses. Additionally, that Fiji’s more resilient reefs (to coral bleaching and their remarkable ability to renew themselves) is being recognized globally by marine scientists and ecologists.”

IFC Country Manager for Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands, Judith Green said: “The challenges faced in Fiji and the Pacific are similar to my home country, Jamaica, and the Caribbean Islands. We need to make sure that development, which is needed in the islands, is sustainable and that that it does not harm the environment.”

Friend and foe

Like many around the world who live by the ocean, the sea is a critical source of income and food for Fijian islanders. And amid the harmful impacts of climate change, it can also be the greatest threat to their survival.

Fiji is one of the most world’s most vulnerable nations to climate change and climate-related disasters. People there face a myriad of tipping points from rising sea levels and coastal erosion to depleted fisheries and more frequent and ferocious extreme weather events.

The Simpsons have experienced devastation before. Rodney Simpson says cyclone Winston in 2016 – one of the most severe cyclones to ever hit the South Pacific - damaged 90 per cent of the reefs located five minutes away.

They saw the coral and ocean regenerate after the onslaught and recognize that their business can play an important role in helping to protect the precious local nature for generations to come. Twice a week, Dive Savusavu hosts a coral and mangrove planting program for children to teach them the importance of conservation.

It’s just one element of how their business is playing a sustainable role in their local community. Another is by training hundreds of local youths as divers, helping to drive local employment in an environmentally friendly industry.

With significant numbers of visitors now returning, the Simpsons say it is critical that more is done to protect the natural assets that attract the lifeblood of the economy.

“If we don't take putting strict measures to protect the reefs, what is going to happen is that we won't have any more reef in future,” said Rodney Simpson.

“As we much as we need visitors, we must also be mindful to keep our oceans healthy for our future,” he said.

Published on 17 th March 2023

- Share full article

Paradise Threatened: Fiji’s War Against Climate Change

The South Pacific nation faces major environmental challenges, from the destruction of coral reefs to rising sea levels. At least one resort is asking tourists to help.

An aerial view of the shore line of Kadavu Island in Fiji. Credit... Asanka Brendon Ratnayake for The New York Times

Supported by

By Ken Belson

- Oct. 24, 2018

Between the international airport in Nadi, Fiji, and the capital city of Suva, the coastal road on the island of Viti Levu is lined with resorts and clogged with tour buses. It’s a route I took several times this spring when I visited friends in Suva, a bustling port city where cruise ships drop anchor year-round and deposit thousands of tourists.

The steady stream of hulking ships is emblematic of Fiji’s popularity, and a major source of income. But the country’s reliance on tourism, combined with vigorous development and the effects of rising global temperatures, have conspired against Fiji’s fragile environment.

The country now faces major environmental challenges, including deforestation, unsustainable fishing practices, and the introduction of invasive species, such as the crown-of-thorns starfish, that have led to the destruction of coral reefs. Rising sea levels has led to the erosion of Fiji’s coastal areas, and the intrusion of saltwater has destroyed farmland and forced residents to move to safer ground.

Before I arrived, I had read that Pacific Island nations were threatened by rising temperatures and sea levels, but it wasn’t until my fifth day there, when my friends and I flew 45 minutes on a small prop plane to the island of Kadavu, that the threat came into full view.

Outside the shack that doubled as the terminal, we climbed into a pickup truck for the bumpy ride to a boat landing. There, we boarded a banana boat for a one-hour ride past shallow reefs and gumdrop specks of land until we reached a lagoon and Matava, a minimalist resort where we planned to stay two nights.

Walking around the grounds, which were built on a steep hill, the damage from Tropical Cyclone Keni, which had swept through the islands in mid-April, three weeks before our arrival, was obvious. Boats in the lagoon were out of commission. A pool that was under construction was a mess. A tree had fallen on top of the dive shop and hit one of the compressors. A path to a nearby village had disappeared in a landslide.

The storm had packed winds of more than 75 miles per hour and dropped nearly a foot of rain on Viti Levu. Kadavu was more directly in the storm’s path, and more than 800 homes were damaged. The storm came just a week after another cyclone, Josie.

Outrigger Fiji

Beach Resort

Keni and Josie were not as strong as the fierce Winston cyclone, which hit Fiji in 2016. But what surprised islanders was that the storms arrived weeks after the cyclone season was supposed to have ended. Although there is still much scientific debate about the impact of climate change on tropical cyclones, to many islanders the timing of the storms are evidence that warming temperatures are leading to shifting weather patterns and leaving the island increasingly vulnerable.

“We literally said, ‘Let’s build the pool because the cyclone season is over,’ and then we got hit,” Luke Kercheval, one of the owners of Matava, told me, adding that the storms had scared off visitors. “We got more rain in a week than some countries get in a year. That’s not normal.”

“Donald Trump might not agree, but it’s 100 percent about climate change,” he added. “I don’t need to be a scientist to figure this out.”

The topic of climate change was everywhere in Fiji, even at the airport in Nadi, where a billboard read, “ Airports Addressing Climate Change .” Fiji’s prime minister, Frank Bainimarama, is the current president of COP23 , the United Nations Climate Change conference. In November, he brought two Fijian children with him to a conference in Bonn to remind delegates that the future of Fiji depends on action against the effects of climate change. Already, one-quarter of the country’s bird species and two-thirds of amphibians are threatened or endangered because of rising sea temperatures and overfishing.

A billboard I spotted captured the mood well: “We are all in the same canoe rising up against climate change.”

The ever-present discussion about Fiji’s fate gave me pause. Would Fiji’s stunning islands look the same in a decade or two? The soft breezes and gentle sunsets and crystal blue water at Matava made it hard to muster alarm. It also made me recall a conversation I had a few days before with Dick Watling, the founder of Nature Fiji, an environmental conservation group.

Mr. Watling arrived in Fiji about 35 years ago and was an astute observer of local politics and the issue of climate change. Over coffee at Cappuccino Republic in Suva, Mr. Watling said that Fiji’s leaders, like those elsewhere in the Pacific region, have become expert at extracting donations from wealthier nations. So he was not surprised that many of Fiji’s problems were being blamed on climate change because it might help attract foreign aid, while also letting lawmakers sidestep thornier issues like unbridled development and lax environmental regulations.

“The government sees this as a major opportunity,” Mr. Watling said. “COP23 is the best tourism marketing program we have ever produced by a country mile.”

Signs of eco-tourism were certainly evident in Fiji. At Matava, solar panels generated most of the electricity, including the lights and fans in our huts. The fruit and vegetables we ate were grown locally and the fish was caught nearby. The eggs came from the chickens at the resort. Bottles, cans and other recyclables were sent back to Viti Levu.

Living off the land did little to protect against Cyclone Keni, though. One of the resort’s boats had flipped upside down and its outboard motors were damaged. The chickens were swept away and the vegetable gardens were destroyed. Several workers at the resort lost their homes. The damage to the reefs made finding fish harder.

I chatted with Maika O’Conna, a boat captain who grew up on Kadavu who said traditional fishing grounds were under attack from poachers, too.

Overfishing and the destruction of the reefs was something I heard discussed back on Viti Levu. One day, I took a trip with my friend Sharon to the Outrigger Fiji Beach Resort , about a two-hour drive from Suva. There, the reef had been damaged by repeated storms and polluted runoff from a nearby stream. With the help of a Japanese aid organization , the hotel built coral gardens that its guests help maintain.

The gardens consist of large metal grates, or propagation racks, placed in the water about 100 feet from the shore. Jonacani Masi, one of the hotel workers, took us out to see them. He brought a dozen cones made of sand mixed with concrete that were the size of my hand. When we reached the grates, he dove underwater and returned with a healthy piece of brown spiky coral that looked like a deer antler. He broke it into smaller, finger-length pieces, and placed each one in a cone packed with quick-drying cement.

Snorkels and masks on, we swam down to the grates and placed the cones in the openings. We saw dozens of other cones with healthy-looking coral stems already there. Together, they created a small reef where none had existed. Fish nipped at my legs, protective of their newly claimed territory. When the coral fingerlings were big enough, they were replanted in the natural reef elsewhere.

“The reef was there for the taking, but it was also abused,” Kinijoji “Kenny” Sarai, Mr. Masi’s boss, said over a lunch of Spanish mackerel marinated in coconut milk, lemon and vinegar. Overfishing by locals depleted the reefs’ aquatic population, and forests cleared by developers led to more pollutants being dumped into rivers that flowed into the ocean, damaging the reefs. “We’re trying to bring the coral back to life.”

Mr. Sarai, who grew up in a nearby village, said the locals are concerned about the damage to the reef. Part of its restoration included helping the reef regenerate, and also trying to convince locals not to fish in reefs being repaired. Though they were reluctant to see restrictions on their fishing rights, many villagers work at the Outrigger and other resorts and recognized that restoring the reef was a key to attracting tourists and, ultimately, preserving their jobs.

“People in Fiji know tourism is the big money earner,” he said. “There’s a national conversation around eco-tourism.”

The next day we set off for Beqa, an island six nautical miles offshore, to meet Sefano Katz. An Israeli by way of Australia, Mr. Katz is a marine biologist and an expert in coral ecosystems. He arrived in Fiji three years ago with the nonprofit group Pacific Blue Foundation to help the locals on Beqa preserve their reef, which is 10 miles wide and one of the largest in Fiji.

He lives in a village of about 200, where he teaches children about composting and restoring mangrove forests, which help protect the coastline from erosion caused by storm surge. He works with the elders to improve the sewage treatment so that polluted water doesn’t seep into the ocean. Villagers are also removing the crown-of-thorns starfish, which eat coral, from the reef.

Mr. Katz said he focuses on steps the villagers can take on their own rather than broad concepts like fighting climate change. He pointed to a study that showed that 48 percent of the damage to the Great Barrier Reef in Australia was from tropical storms and cyclones, and another 42 percent from crown-of-thorns starfish, whose population has exploded because of an increase in phosphorus runoff from sewage, and other issues. This, he said, was similar in Fiji.

“People protect what they understand,” he said. “That’s the way to make change.”

Mr. Katz took us to meet Filipe Kirikirikula, the 60-year-old head of the council of elders. We sat outside his home in the middle of the well-kept village by the beach. He supported Mr. Katz’s mission, which he said required changing age-old habits. “Most of the people just abuse the environment,” he said. “It’s quite difficult to teach them about conservation. People here have their own freedom.”

The days of going out on the reef with a spear to catch dinner were disappearing, he said. So he supported a plan to create an area to raise clams and fish that would be protected from poachers. It would also repopulate the reefs, which in turn would attract more divers who could be charged a fee, he said.

As the afternoon waned, Mr. Katz took us back to the mainland on his boat. Beqa, which legend has it, is home to the Fijian shark god, Dakuwaqa , faded from view as we skipped over the waves and around the swells.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter , Instagram and Facebook . Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.

Ken Belson covers the N.F.L. He joined the Sports section in 2009 after stints in Metro and Business. From 2001 to 2004, he wrote about Japan in the Tokyo bureau. More about Ken Belson

Advertisement

Looking for a story, magazine article, event, topic, country, etc try searching...

- More Information

One year on: Fiji’s tourism sector ‘exceeding expectations’

Fiji’s tourism sector leaders are celebrating the one-year anniversary of Fiji’s reopening to tourists, having seen over half a million tourists visit the nation since December 1, 2021.

Covid-19 ravaged Fiji’s tourism-dependent economy, with an estimated 115,000 people suddenly out of work when borders shut, and hotels and resorts closed their doors.

Fiji Airways CEO and Managing Director, Andre Viljoen, puts the success of the reopening down to “months of meticulous strategising and preparation.”

Tourism Fiji says 520,312 visitors have come to Fiji since December 1, 2021. That is 63% of pre COVID-19 levels (in 2019). In October, arrivals hit 90% of pre COVID-19 visitor numbers.

The majority of these visitors are coming from Australia, followed by New Zealand and the United States. But this week, Fiji Airways has also launched a twice-weekly service to Canada, and it hopes to resume service to other destinations soon.

Tourists are also staying longer in the country according to the national tourism authority, and they are spending more at FJ$271 per night, up 12% from pre-COVID-19. Viljoen says in reopening when it did, Fiji was “miles ahead of many other Pacific Island countries and indeed, other much larger nations in other parts of the world.”

Chris Cocker, the CEO of the Pacific Tourism Organisation, concurs, saying the air access Fiji enjoys through its national carrier, has been critical to this. He says Fiji’s industry has also demonstrated that preparation, and coordination is key. However he expects competition from other markets to intensify.

“We need to understand as well that the whole world is reopening. And it’s very competitive. In this case, it’s not only our part of the Pacific. If our packages are not as competitive, you’ve got Bali and also the other destinations [that] they’ll go to in this case.”

Tourism Fiji CEO, Brent Hill says the rate of recovery is exceeding expectations, “and the impact can be seen in our economy with tourists buzzing in resorts, towns, as well as villages as people experience the true Fiji. The resilience of the Fijian people, the care we show for each other and our communities, our natural hospitality and happiness, and our commitment to welcoming back visitors is why Fiji has been successful in standing out as a destination.”

Fiji Airways’ CEO is bullish about future bookings. Viljoen says while initially Fiji benefited from pent-up demand from people sick of lockdowns, that is no longer the case.

“When we look at bookings held, tickets sold to people that would travel in the future from the start of December until the end of May with 30% ahead of 2019 bookings, that’s enormous. We still have 30% of our markets still closed, we’ve got Japan and Hong Kong closed, and some South Pacific countries still opening slowly.”

With Fiji’s national election scheduled for December 14, the government of Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama will be hoping that some of the celebratory atmosphere that Fiji has witnessed this week, will serve them well in polling.

Bainimarama says with the reopening, the country has achieved what many had said was impossible.

“Over 100,000 Fijians have re-entered the workforce,” he says in a Facebook post this week, continuing, “Nothing makes me prouder than seeing our people back in jobs they love.”

Share this article:

Related posts.

Fiji Business Briefs: Fuel prices up, Vanua Levu road project, Movers and Shakers

Small Singapore company to monopolise all gold trading in PNG, says industry

Palau scrambles after cyberattack cripples financial systems

Fiji Business Briefs: RBF on Fiji’s outlook, Aviation school to expand

Advertisement

Coastal resource management and tourism development in Fiji Islands: a conservation challenge

- Published: 08 June 2020

- Volume 23 , pages 3009–3027, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Shalini Singh 1 , 2 ,

- Jahangeer A. Bhat ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2451-8499 2 nAff3 ,

- Shipra Shah 2 &

- Nazir A. Pala 4

2768 Accesses

16 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The tourism sector has been a key driver of socioeconomic progress in Fiji Islands since the 1980s, in comparison with other industries such as agriculture, fisheries, and forestry. Fiji currently plans to further expand its tourism industry into a 2 billion FJD sector, which places great pressure on the coastal environment and resources that attract more than 500,000 tourists per year. Unplanned tourism development has adverse impacts on the environment and dependent communities, which is often attributed to weak governance and poorly enforced regulations. In Fiji, the industry has been recognized as responsible for mangrove clearance and coastal degradation, both of which aggravate problems such as coastline erosion, vulnerability to natural disasters, fish stock declines, poor water quality, pollution, and biodiversity loss. Though the country has national legislations in place, as well as regional and international collaborations to manage its ocean resources, it lacks the capacity and resources to implement environment policy, planning, and regulation. There is a need to strengthen governance and community capacity to address problems of effective enforcement of legislation and ensure the conservation, management, and sustainable utilization of marine and coastal resources.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

(Photo by: Shalini and Jahangeer)

(Photo by: Shalini and Jahangeer)

Similar content being viewed by others

Coastal and Ocean Tourism

Marine Tourism and the Blue Economy: Perspectives from the Mascarene and Pacific Islands

Disentangling Trade-Offs Between the State of Coastal Ecosystems with Human Well-Being and Activities as a Strategy Addressing Sustainable Tourism

ABM (Australian Bureau of Meteorology), & CSIRO. (2014). Climate variability, extremes & change in the western tropical Pacific: New science & updated country reports 2014 . Collingwood, VIC: Centre for Australian Weather & Climate Research.

Google Scholar

Agrawal, A., & Gibson, C. C. (1999). Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Development, 27 (4), 629–649.

Agrawala, S., Ota, T., Risbey, J., Hagenstad, M., Smith, J., van Aalst, M., et al. (2003). Development and climate change in Fiji: Focus on coastal mangroves . Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Barbier, E. B., Hacker, S. D., Kennedy, C., Koch, E. W., Stier, A. C., & Silliman, B. R. (2011). The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecological Monographs, 81 (2), 169–193.

Baztan, J., Chouinard, O., Jorgensen, B., Tett, P., Vanderlinden, J.-P., & Vasseur, L. (2015). Coastal zones: Solutions for the 21st century (pp. 1–343). Amsterdam: Elseiver.

Bell, J. D., Kronen, M., Vunisea, A., Nash, W. J., Keeble, G., Demmke, A., et al. (2009). Planning the use of fish for food security in the Pacific. Marine Policy, 33, 64–76.

Breton, F. (2006). Report on the use of the ICZM indicators from the WG - ID. A contribution to the ICZM evaluation . Version 1. ‘Indicators and data’ working group (WG-ID) of the European ICZM expert group. Universitat Antònoma de Barcelona and European Environment Agency. Retrieved May 17, 2017 from http://ec.europa.eu/environment/iczm/pdf/report_wgid.pdf .

Brown, C. J., Jupiter, S. D., Albert, S., Klein, C. J., Mangubhai, S., Maina, J. M., et al. (2017). Tracing the influence of land-use change on water quality & coral reefs using a Bayesian model. Scientific Reports, 7, 4740. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05031-7 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bureau of Statistic (BoS) Fiji. (2017). Census results www.fiji.gov.fj

Caldwell, M., Churcher Hoffmann, T., Palumbi, S., Teisch, J., & Tu, C. (2009). Pacific ocean synthesis: Scientific literature review of coastal and ocean threats, impacts and solutions (pp. 1–170). California: The Woods Center for the Environment, Stanford University. Retrieved June 26, 2017 from http://www.centerforoceansolutions.org/PacificSynthesis .

Carpenter, R. A., & Maragos, J. E. (Eds.). (1989). How to assess environmental impacts on tropical islands and coastal areas . South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) Training Manual, Environmental and Policy Institute, East–West Center, Honolulu.

Chandra, A. (2011). A deliberate inclusive policy (DIP) approach for coastal resources governance: A Fijian perspective. Coastal Management, 39 (2), 175–197.

Chang, S. E., Adams, B. J., Alder, J., Berke, P. R., Chuenpagdee, R., Ghosh, S., et al. (2006). Coastal ecosystems and tsunami protection . Report to the National Science Foundation of the USA.

Chin, A., Lison De Loma, T., Reytar, K., Planes, S., Gerhardt, K., Clua, E., et al. (2011). Status of coral reefs of the Pacific & Outlook: 2011 . Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (pp. 1–260).

Clarke, W. C. (1991). Time and tourism: An ecological perspective. In M. L. Miller & J. Auyong (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1990 congress on coastal and marine tourism (pp. 387–393). Honolulu: National Coastal Research and Development Institute.

Convention on biological diversity. (2014). CBD: Fiji’s 5th national report to United Nations . Retrieved November 28, 2017 from https://www.cbd.int .

Costanza, R., & Farley, J. (2007). Ecological economics of coastal disasters: Introduction to the special issue. Ecological Economics, 63, 249–253.

Dutra, L. X. C., Haywood, M. D. E., Singh, S. S., Piovano, S., Ferreira, M., Johnson, J. E., Veitayaki, J., Kininmonth, S., & Morris, C. W. (2018). Effects of climate change on corals relevant to the Pacific Islands. Science Review , 132–158.

Ellison, J. (2009). Wetlands of the Pacific Island region. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 17 (3), 169–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-008-9097-3 .

Article Google Scholar

Ellison, J. C., & Fiu, M. (2010). Vulnerability of Fiji’s mangroves and associated coral reefs to climate change: A review . Suva: WWF South Pacific.

Fiji Budget 2017/2018— budget report (2017). Retrieved March 21, 2018 from www.pwc.com .

Fiji Bureau of Statistics (FBoS). (2017). Fiji’s earnings from tourism - December & annual report no: 9 . Retrieved October 3, 2017 from http://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/ .

Fiji State of Environment Report. (2013). Secretariat of the Pacific regional environment programme (SPREP) Apia, Samoa.

Fijian Tourism 2021 (Plan), Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism (2017). www.fiji.gov.fj/ .

Gibbs, D., Jonas, A., & While, A. (2002). Changing governance structures and the environment: Economy–environment relations at the local and regional scales. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 4 (2), 123–138.

Gonzalez, R., Ram-Bidesi, V., Leport, G., Pascal, N., Brander, L., Fernandes, L., et al. (2015). National marine ecosystem service valuation: Fiji (pp. 1–91). Suva: MACBIO (GIZ/IUCN/SPREP).

Greenhalgh, S., Booth, P., Walsh, P., Korovulavula, I., Copeland, L., & Tikoibua, T. (2018). Mangrove restoration: An overview of the benefits and costs of restoration . Prepared as part of the RESCCUE-SPC Fiji project. University of South Pacific, Institute of Applied Sciences, Suva, Fiji.

Hall, C. M. (1996). Environmental impact of tourism in the Pacific. In C. M. Hall & S. Page (Eds.), Tourism in the Pacific: Issues and cases (pp. 65–80). London: Routledge.

Hall, C. M. (2001). Trends in ocean and coastal tourism: The end of the last frontier? Ocean and Coastal Management, 44, 601–618.

Heider, C. (2013). MESCAL carbon assessment: Rewa delta mangrove reference levels & emissions due to mangrove conversion . Oregon: Watersheds Professional Network LLC (WPN).

Hills, T., Carruthers, T. J. B., Chape, S., & Donohoe, P. (2013). A social and ecological imperative for ecosystem-based adaptation to climate change in the Pacific Islands. Sustainability Science, 8 (2), 1–15.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., & Ridgway, T. (2016). Reviving Melanesia’s ocean economy: The case for action—2016 . Gland: WWF International.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Ridgway, T., Smits, M., Chaudhry, T., Ko, J., Beal, D., et al. (2016). Reviving Melanesia’s ocean economy: The case for action (pp. 1–64). Gland: WWF International.

Howard, J., Hoyt, S., Isensee, K., Telszewski, M., & Pidgeon, E. (Eds.). (2014). Coastal Blue Carbon: Methods for assessing carbon stocks and emissions factors in mangroves, tidal salt marshes, and seagrasses . Arlington, VA: Conservation International, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO, International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Hughes, B., Aalbersberg, W. G. L., Ronadue, D., & Hale, L. (2003). Sustainable coastal resource management for Fiji: A background paper prepared for the Fiji National workshop on integrated coastal management . USP Electronic Research Repository (pp. 1–48).

Hutomo, M. (2009). Kebijakan, Strategi dan Rencana Aksi Pengelolaan Ekosistem Lamun di Indonesia. Makalah disampaikan pada Lokakarya Nasional I Pengelolaan Ekosistem Lamun, 18 November 2009, Jakarta: Sheraton Media.

Investment Fiji. (2016). Tourism . Retrieved October 27, 2017 from http://www.investmentfiji.org.fj .

IPCC. (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis . Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA (pp. 1–1535).

Kay, R. C., & Alder, J. (2005). Coastal planning and management (pp. 1–380). London: E&F Spon.

Lane, M. B. (2006). The governance of coastal resources in Fiji: An analysis of the strategic issues . Apia: SPREP.

Lane, M. B., McDonald, G. T., & Morrison, T. (2004). Decentralisation and environmental management in Australia: A comment on the prescriptions of the Wentworth Group. Australian Geographical Studies, 42 (1), 102–114.

Lenzen, M., Sun, Y.-Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y.-P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x .

Lester, S. E., McLeod, K. L., Tallis, H., Ruckelshaus, M., et al. (2010). Science in support of ecosystem-based management for the US west coast and beyond. Biology Conservation, 143, 576–587.

Levett, R., & McNally, R. (2003). A strategic environmental assessment of Fiji’s tourism development plan . Suva: Worldwide Fund for Nature South Pacific Programme (WWF-SPP).

Levett, R., McNally, R., & Malani, M. (2004). Strategic environmental assessment of Fiji Islands national tourism plan. In Asian Development Bank (Ed.), Pacific regional environmental strategy 2005–2009, Volume II: Case studies . Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Lovell, E. R., & McLardy, C. (2008). Annotated checklist of the CITES-listed corals of Fiji with reference to Vanuatu, Tonga, Samoa and American Samoa . JNCC Report No. 415. Peterborough, UK: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

Lovell, E., Sykes, H., Deiye, M., Wantiez, L., Garrigue, C., Virly, S., et al. (2004). Status of coral reefs in the southwest Pacific: Fiji, Nauru, New Caledonia, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, & Vanuatu. In C. Wilkinson (Ed.), Status of coral reefs of the world: 2004 (Vol. 2, pp. 337–362). Townsville, QLD: Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Mills, M., Jupiter, S., Adams, V., Ban, N., & Pressey, B. (2011). Can management actions within the Fiji locally managed marine area network serve to meet Fiji’s national goal to protect 30% of inshore marine areas by 2020? Wildlife Conservation Society and ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, Suva, Fiji (pp. 1–16).

Milne, S. (1990). The impact of tourism development in small Pacific Island states. New Zealand Journal of Geography, 89, 16–21.

Mimura, N., & Nunn, P. (1998). Trends of beach erosion and shoreline protection in rural Fiji. Journal of Coastal Resources, 14 (1), 37–46.

Minerbi, L. (1992). Impacts of tourism development in Pacific Islands . San Francisco: Greenpeace Pacific Campaign.

Moberg, F., & Folke, C. (1999). Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecological Economics, 29 (2), 215–233.

Morrison, T. H., McDonald, G. T., & Lane, M. B. (2004). Integrating natural resource management for better environmental outcomes. Australian Geographer, 35 (3), 243–259.

Mosley, L. M., & Aalbersberg, W. G. L. (2003). Nutrient levels in sea and river water along the ‘Coral Coast’ of Viti Levu, Fiji. South Pacific Journal of Natural Sciences, 21, 35–40.

Movono, A. R. N. (2012). Tourism’s impact on communal development in Fiji: A case study of the socio - economic impacts of the Warwick resort and spa and the Naviti resort on the indigenous Fijian villages of Votua and Vatuolalai . MA thesis, University of the South Pacific.

NFMV. (2010). On the continuing destruction of Fiji’s rivers & streams . Paper presented by Nature Fiji-MareqetiViti to Fiji’s National Environment Council meeting, Fiji.

Nobre, A. M. (2011). Scientific approaches to address challenges in coastal management. Marine Ecological Progress Series, 434, 279–289.

Orams, M. (1999). Marine tourism: Development, impacts and management . London: Routledge.

Pendleton, L., Donato, D. C., Murray, B. C., Crooks, S., Jenkins, W. A., Sifleet, S., et al. (2012). Estimating “Blue Carbon” emissions from conversion and degradation of vegetated coastal ecosystems. PLoS ONE, 7 (9), e43542.

CAS Google Scholar

Perrottet, J., Garcia, A. F., Nicholas, D., Simpson, D., Kennedy, I., Bakker, M., Wayne, S., Wright, E., Schlumberger, C., Saslavsky, D., Bofinger, H., Nevill, H., Chugh, N., Baptista, A. M., Zhou, V. J., & Obeyesekere, A. (2016). Pacific possible: Tourism report . The World Bank, IBRD. IDA. Retrieved August 5, 2017 from www.worldbank.org .

Polidoro, B. A., Carpenter, K. E., Collins, L., et al. (2010). The loss of species: Mangrove extinction risk and geographic areas of global concern. PLoS ONE, 5, 310095.

Rao, N. S., Carruthers, T. J. B., Anderson, P., Sivo, L., Saxby, T., Durbin, T., Jungblut, V., Hills, T., & Chape, S. (2013). An economic analysis of ecosystem-based adaptation and engineering options for climate change adaptation in Lami Town, Republic of the Fiji Islands . A technical report by the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme SPREP 2013, Apia, Samoa. Retrieved April 28, 2018 from http://www.sprep.org/attachments/Publications/Lami_Town_EbA_Technical.pdf .

Ribot, J. C. (2002). Democratic decentralization of natural resources: Instituting popular participation . Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

Satumanatpan, S., & Pollnac, R. (2019). Resilience of small-scale fishers to declining fisheries in the gulf of Thailand. Coastal Management . https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2020.1689769 .

Short, F. T., Coles, R., Fortes, M. D., Victor, S., Salik, M., Isnain, I., et al. (2014). Monitoring in the Western Pacific region shows evidence of seagrass decline in line with global trends. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 83, 408–416.

Skelton, P. A., & South, G. R. (2006). Seagrass biodiversity of the Fiji and Samoa islands, South Pacific. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 40, 345–356.

Sloan, J. (2017). How does the law protect mangroves in Fiji? Feb 14, 2017, http://www.sas.com.fj/ocean-law-bulletins/how-does-the-law-protect-mangroves-in-fiji .

Spalding, M., Kainuma, M., & Collins, L. (2010). World atlas of mangroves . London: Earthscan.

SPC. (2008). Status report: Nearshore and reef fisheries and aquaculture . Noumea: Secretariat of the Pacific Community.

Statista. (2016). Tourism Worldwide: Global tourism industry—Statistics and facts . Retrieved August 4, 2017 from http://www.statista.com .

Sulu, R. (2007). Status of Coral Reefs in the Southwest Pacific, 2004 . Suva: IPS Publications, University of the South Pacific.

Sykes, H., & Morris, C. (2009). Status of Coral Reefs in the Fiji Islands. In: C. Whippy-Morris (Ed.), Southwest Pacific Status of Coral Reefs report 2007 . CRISP, Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Program, Noumea. Retrieved August 24, 2017 from www.crisponline.net/CRISPPRODUCTS/Reefknowledgeandmonitoring/tabid/311/Default.aspx .

Torell, E., Crawford, B., Kotowicz, D., Herrera, M. D., & Tobey, J. (2010). Moderating our expectations on livelihoods in ICM: Experiences from Thailand, Nicaragua, and Tanzania. Coastal Management, 38 (3), 216–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2010.483166 .

UNDP. (2012). Fiji locally-managed marine area network, Fiji . Equator Initiative Case Study Series, New York.

UNDP/IUCN. (2006). Mangroves for the future: A strategy for promoting investment in coastal ecosystem conservation, 2007–2012 .

UNEP. (2016). Summary of the sixth global environment outlook regional assessments: Key findings and policy messages . UNEP United Nations Environment Assembly.

UNEP/SOPAC. (2005). Environmental Vulnerability Index—Fiji . United Nations Environment Program/Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience Commission. Retrieved November 29, 2017 from www.vulnerabilityindex.net/ .

United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) report. (2016). UNWTO, Madrid.

Veitayaki, J. (1997). Traditional marine resource management practices used in the Pacific Islands: An agenda for change. Ocean and Coastal Management, 37, 123–136.

Veitayaki, J. (1998). Traditional and community-based marine resources management system in Fiji: An evolving integrated process. Coastal Management, 26 (1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920759809362342 .

Watling, D., & Chape, S. (Eds.). (1992). Environment Fiji—The national state of the environment report . Gland: International Conservation Union.

Wawo, M., Wardiatno, Y., Adrianto, L., & Bengen, D. G. (2014). Carbon stored on seagrass community in Marine Nature Tourism Park of Kotania Bay, Western Seram, Indonesia. JMHT, 1, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.7226/jtfm.20.1.51 .

WCS. (2009). Wildlife Conservation Society, Annual report, South Pacific Program 2009.

Wondolleck, J. M., & Yaffee, S. L. (2000). Making collaboration work: Lessons from innovation in natural resource management . Washington, DC: Island Press.

World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). (2018). Travel and tourism economic impact 2018 Fiji . London: WTTC.

Download references

Author information

Jahangeer A. Bhat

Present address: College of Horticulture and Forestry, Rani Lakshmi Bai Central Agricultural University, Jhansi, UP, 284003, India

Authors and Affiliations

Pacific Centre for Environment and Sustainable Development, University of the South Pacific, Lower Laucala Campus, Laucala Bay Road, Suva, Fiji

Shalini Singh

College of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Fiji National University, Koronivia, Nausori, Fiji

Shalini Singh, Jahangeer A. Bhat & Shipra Shah

Division of Silviculture and Agroforestry, Faculty of Forestry, SKUAST-K, Benhama-Watlar, Ganderbal, J&K, 191201, India

Nazir A. Pala

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jahangeer A. Bhat .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Singh, S., Bhat, J.A., Shah, S. et al. Coastal resource management and tourism development in Fiji Islands: a conservation challenge. Environ Dev Sustain 23 , 3009–3027 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00764-4

Download citation

Received : 03 October 2018

Accepted : 02 May 2020

Published : 08 June 2020

Issue Date : March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00764-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Coastal habitats

- Resource management

- Development

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Development Policy Centre

- Australian Aid Tracker

- Aid Profiles

- PNG Databases

- Publications

A greener future for tourism in Fiji?

Recently I arrived back in Fiji after nearly two years away. One of the first changes I noticed, on the drive from Nadi to Suva, was the proliferation of the African tulip tree. It’s a beautiful tree, with huge scarlet flowers – hence its introduction a few decades ago as a garden ornamental. Presumably no one involved with bringing it to the main islands of Fiji realised how it would spread, outcompeting the native trees and taking over large swathes of forest, so that it is now one of the worst invasive species in Fiji.

Driving along the spectacular south coast road of Viti Levu, as many newly arrived visitors do, I wondered how many tourists think they are looking at a beautiful natural forest, and how many recognise a highly disturbed and degraded ecosystem. I speculated that, if Fiji markets itself as a pristine paradise, a ‘green’ destination – as it should – this might draw increasing numbers of environmentally knowledgeable tourists, who will see through the ‘unspoilt paradise’ posters and ask what Fiji is doing to fix its environmental problems.

The loss of native trees has a knock-on effect for entire ecosystems, affecting native species from insects to birds and bats (the only native mammals here). Other introduced and now invasive species that have dramatically changed Fiji’s natural environment include the mongoose and the cane toad, both seen almost everywhere on the main islands – unlike the native ground-dwelling birds, iguanas and snakes which, as a direct result, are now extinct or found only on remote, outer islands.

Invasive species are a very visible environmental problem that needs addressing, but this has so far proved too difficult. Any solution requires collaboration between land managers, different government agencies, conservationists and researchers. It will take considerable time, effort and money.

By coincidence, the same week I arrived, Fiji began consultations towards revising its national tourism strategy . I attended the first of a series of webinars, organised by the Ministry of Commerce, Trade, Tourism and Transport (MCTTT) and supported by the International Finance Corporation (IFC). This ‘public–private dialogue’ had the key stakeholders MCTTT, Fiji Tourism, Fiji Airways, the Fiji Hotel and Tourism Association, and Duavata Sustainable Tourism Collective sharing their views and perspectives.

Fiji’s new strategy is to be called the National Sustainable Tourism Framework. ‘Sustainable’ is a ubiquitous word these days, but it’s good to have it in the title. It at least indicates a medium- to long-term planning approach, rather than short termism.

The word was first used around the idea of environmental protection – the classic definition of sustainable development was coined by the United Nations Brundtland Commission in 1987 as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. It’s now used much more widely, beyond the environment. We understand that sustainability has other facets – social, cultural, economic – and importantly, that addressing one while ignoring the others will ultimately lead to failure. Still, we shouldn’t forget the word’s environmental origins.

Listening to the webinar, I was very glad that Duavata Sustainable Tourism Collective had been included in the panel of speakers. Duavata is an association of small tourism businesses built on and united by respect for Fiji’s environment and cultural heritage – my own agritourism business is a member. Inviting Duavata to the table indicates a recognition of the important role that environmental and socio-cultural dimensions play in distinguishing Fiji from its competitors in the international tourism marketplace. Hopefully it also means that sustainability in these areas will be addressed within the new national framework. If Fiji pitches itself as an unspoilt paradise – with intact traditions, culture and environment – then it needs to take care of these vital assets.

Tourism is Fiji’s biggest industry. Directly or indirectly, it touches on the lives of all Fijians. Similarly, the whole country – its natural beauty, its friendly people, its warm ocean and colourful fish and corals; but also its burning sugarcane stubble, its traffic jams, its invasive species and its degraded forests – is what is ‘on sale’ to tourists. And the more tourists leave their resorts and investigate the ‘real Fiji’, the more important it becomes for the industry – and the country’s leaders – to look at the problem issues.

Tourists are already voicing their concerns about Fiji’s environmental issues, with the help of the international media. The recent fight-back by two Australian surfers and a local landowner against damage to the reefs around Malolo Island is an example. The court ruling – a hefty fine for the Chinese developers – conveyed a positive message, but whether it signifies a genuine orientation of government focus to Fiji’s environmental problems remains to be seen.

Much of the MCTTT webinar was about statistics, trends and targets, as tourism reboots. The pandemic and the climate – we’ve had 14 tropical cyclones over just six recent years – were cited as obvious risks for the industry. But not many of the panellists mentioned the importance of protecting and improving the environment. Environmental degradation and loss may be equally significant threats. And, crucially, measures to recover and protect the environment, through better management of forests, water, reefs and other natural resources, contribute to resilience – of the country’s people, and its economy – in the face of climate and other shocks.

Fiji and tourism are inseparable. Rebuilding the tourism industry should include a renewed drive to restore and protect the nation’s natural environment, and facilitate its sustainable management by its community owners.

The challenge shouldn’t be underestimated. Invasive species are only one environmental issue that needs to be addressed – there are many more. At the government level, effective cross-sectoral policy and planning will be essential – not currently a strong point in Fiji. And if Fiji and tourism are inseparable, then everyone needs to be meaningfully involved in finding new ways forward.

But surely restoring Fiji’s natural assets is worth the effort. Let’s not compromise the ability of future generations of Fijians to meet their needs – but instead make sure that the foundations are sound and healthy, for future industries and livelihoods. If the tourism recovery drive can be used to catalyse such a refocus, this will be a positive outcome from the pandemic.

Anne Moorhead is co-owner of KokoMana Pte Ltd, an agritourism business in Savusavu, Fiji. The views are those of the author only.

Related posts:

- A Fijian business surviving COVID without tourists or government help – just

- Second wave of COVID-19 cases shakes up Fiji

- Diaspora, loved ones and COVID-19

- COVID-19: a Fijian businesswoman’s perspective

- Meraia Taufa Vakatale: anti-nuclear activist and feminist trailblazer

Anne Moorhead

Anne Moorhead is a freelance writer and editor specialising in sustainable development with a focus on the Pacific islands region. She works as a consultant editor for Devpolicy Blog. Anne is also co-owner and chocolate maker at KokoMana in Savusavu, Fiji.

Leave a Comment X

Sign me up for the fortnightly newsletter!

Don't subscribe All new comments Replies to my comments Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting.

Share on Mastodon

Fiji reopens to foreign tourists for first time in nearly two years

The Reuters Daily Briefing newsletter provides all the news you need to start your day. Sign up here.

Reporting by Colin Packham in Canberra; Editing by Simon Cameron-Moore

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Tajikistan's foreign ministry on Saturday rejected a claim by a top Russian security official that Ukraine's embassy in the Tajik capital was recruiting mercenaries to fight against Russia.

Government-backed Pellegrini on course to win Slovak presidential election

At stake is whether Prime Minister Robert Fico, who took power in October for the fourth time, will get an ally in the presidential palace or an opponent who could challenge his pro-Russian stance and plans to reform criminal law and the media.

Airline passengers in parts of the United Kingdom and Ireland faced travel disruption at airports on Saturday due to flight cancellations as a storm swept across both countries and left thousands of Irish homes with power outages.

- Get involved

Fijians affected by tourism job losses recover from pandemic

May 24, 2022.

Meresiana Salauca, Naidi Village, Savusavu (Photo: UNDP)

Meresiana Salauca of Naidi village in Savusavu, Fiji, was one of the unfortunate workers laid off from one of the resorts on the island - as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit Fiji with its first wave in 2020. The 56-year-old is a single mother of two, who worked as a massage therapist at the resort, had saved $500 and used it to start a canteen business.

Soon after, the Fijian government announced the COVID-19 Concessional Support Package for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) through which she qualified and received a $3,000 grant to continue her business operations. However, things did not go as planned because she was operating during one of Fiji's darkest periods, when borders were closed, and movement was restricted.

Meresiana was overcome with emotion as she shared her experience at the Financial Literacy Training and seedling distribution, in the villages of Naidi, Waivunia and Vivili between 2-10 May 2022. “Many times, I wanted to close my canteen because there were so many credit requests, but thankfully, my children kept encouraging me to keep going. I'm grateful for their support and encouragement and this training has taught me how to budget my finances, particularly for families, because there is a lot of money committed to village obligations, but I have learnt that even saving $5 is a very good strategy,” she said. Ms. Salauca worked as a Japanese translator for the Freebird Institute in Namaka, Nadi, before entering the tourism industry.

Funded by the UN Development Programme’s Multi-Partner Trust Fund (MPTF) COVID-19 recovery assistance project , the financial literacy training was conducted by the Financial Management Counsellors Association of Fiji (FMCA) - a group of financial and business management bankers with community development expertise. The support also included the distribution of vegetable seedlings, agricultural resource materials, and IT equipment such as a multimedia projector, pull-up screen, and hard drive to the villages to enable online learnings and workshops.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on these villages, resulting in job losses, reduced hours, and loss of livelihood.

Vika Teki, Waivunia Village, Savusavu (Photo: UNDP)

68-year-old Vika Teki of Waivunia village is a handicraft maker with more than a decade of experience. She was also greatly impacted by the pandemic because she was heavily reliant on tourists visiting the hidden paradise to buy her handicrafts, which included necklaces, mats, baskets, and bracelets, among other things.

"I relied heavily on this business, but since the borders closed and there were no tourists, I couldn't make or sell any more. So, during the lockdown, we had to find alternative source of income, such as fishing, but now that the borders have reopened, business is gradually returning to normal."

She also runs a catering business, where she teaches other village women how to bake and encourages them not to rely solely on one source of income.

Ruveni Barrack, Vivili Village, Savusavu (Photo: UNDP)

Ruveni Barrack, a massage therapist by profession who now runs his own Massage Therapy Academy in Savusavu said the MPTF COVID-19 Recovery Assistance came at a time when they needed it the most, especially coming out of a very dark period, and it has encouraged them to be business minded. “I am grateful to UNDP for bringing this training to Vivili because it has encouraged me to continue training Fijians interested in becoming massage therapists in our hotels and to expand this business. This training has taught me that family comes first and that it is critical to involve family in decision making.” Mr. Barrack is also a farmer who sells root crops and vegetables during harvest to nearby resorts, restaurants in town, and the Savusavu Municipal Market with hopes to expand his farming business and raise more capital with the eight varieties of vegetable seedlings he received.

60 participants from the financial literacy training held at Naidi village, Savusavu. (Photo: UNDP)

A whole family approach was used during the financial literacy training to encourage the 200 participants to appreciate and leverage the knowledge and skills of members of their families when managing and planning their finances. Of the 200 participants, 76 of them were women.

The training was aimed to strengthen the financial competencies of the individuals who will have a direct impact on their families, educate farmers about financial services, allowing them to make better informed decisions about managing family finances and how to move forward following the effects of COVID-19 on their family, business, and income.

Participants at Waivunia village with their certificates and seedlings. (Photo: UNDP)

For more information, please contact:

Akosita Talei, Inclusive Growth - Communications and Research Officer, UNDP Pacific Office in Fiji, Email: [email protected]

Related Content

Building a Sustainable Future Together: Kiribati’s Journey with Cooperatives

In the enchanting Pacific nation of Kiribati, an inspiring and groundbreaking initiative is underway to empower local communities and ensure a brighter, sustainab...

Press Releases

“meet tuya: supporting the pacific sustainable development pathways as the new multi-country resident representative”.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) multi-country Pacific Office in Fiji is delighted to announce Munkhtuya (Tuya) Altangerel as its new Resident Repr...

Publications

Multi-country programme document (2023-2027).

This 5-year multi-country programme is derived from the Pacific Cooperation Framework, 2023-2027, and the national plans of the 14 Pacific Island Countries and Te...

New opportunities for women in Kiribati’s Virgin Coconut Oil Facility

The Tebamuri Virgin Coconut Oil tab-South facility will generate more income and revenue for the people of Kiribati, an island nation with a population of over 10...

Crop protection systems for high quality vegetable production

Nausori highland village is in the interior of Viti Levu, on the border of Nadroga/Navosa and Ba provinces. The village has a population of over 300 people, and t...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Harmonising climate change adaptation and mitigation: The case of tourist resorts in Fiji

Tourism in island states is vulnerable to climate change because it may result in detrimental changes in relation to extreme events, sea level rise, transport and communication interruption. This study analyses adaptation to climate change by tourist resorts in Fiji, as well as their potential to reduce climate change through reductions in carbon dioxide emissions. Interviews, site visitations, and an accommodation survey were undertaken. Many operators already prepare for climate-related events and therefore adapt to potential impacts resulting from climate change. Reducing emissions is not important to operators; however, decreasing energy costs for economic reasons is practised. Recommendations for further initiatives are made and synergies between the adaptation and mitigation approaches are explored.

1. Introduction

Fiji is the largest tourism destination in the South Pacific but international arrivals have fluctuated over the last 5 years because of a series of detrimental events, such as the political coup in Fiji in 2000, the terrorist attack in the United States on 11 September 2001, the Bali attack in 2002, and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome outbreaks in Asia in 2003. These events have shown that tourism in Fiji is vulnerable to both internal and external events. Tourism is also vulnerable to natural hazards and disasters, such as earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, droughts, and cyclones. Climate change plays an important role in disaster management, because it is likely to affect Fiji through sea level rise and storm surge, changing temperature and precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events. As in other developing countries, this vulnerability is aggravated by limited institutional capacity, non-availability of technologies, ill-enforced regulatory frameworks, and lack of financing (B. Challenger, Presentation at the IPCC Outreach Workshop on Mitigation, September 23–24, 2002). Climate change has to be seen in a multi-stress context of wider environmental, social, and political changes and pressures ( Wilbanks, 2003 ).

While the wider climate change debate has until recently mainly focused on mitigation ( Burton et al., 2002 ; Wilbanks, 2003 ; Nicholls and Lowe, 2004 ), the sparse research specifically dealing with tourism and climate change has largely concentrated on tourism's vulnerability and adaptation to climate change (e.g., Elsasser and Buerki, 2002 ; Scott, 2003 ; Scott et al., 2003 ). Both the tourism industry and researchers have identified a threat to tourism resulting from climate change, especially in alpine areas, small island states, and developing countries ( World Tourism Organisation, 2003 ). Climate change is also likely to affect global tourist flows as a result of the changing attractiveness of both destinations and countries of origin ( Hamilton et al., 2005 ). Despite an inherent interest in ‘protecting’ the tourism industry, there is increasing awareness that tourism is an important contributor to climate change through its consumption of fossil fuels and resulting greenhouse gas emissions ( Becken, 2002 ; Gössling, 2002 ). The wider literature on climate change now emphasises that neither adaptation nor mitigation should be implemented independently, but that an integrated framework for sustainable development should be envisaged ( IPCC, 2001 ; Nicholls and Lowe, 2004 ). In the same way, research on climate change and tourism will benefit from taking into account the multiple interactions between climate, tourism, and the wider environment ( Dubois, 2003 ; Viner and Amelung, 2003 ).

This study seeks to enhance understanding of climate change issues associated with tourism from both adaptation and mitigation perspectives, and explores synergies between the two responses. A localised approach is taken (as suggested by Wilbanks (2003) ), with the research being confined geographically to the main tourist destinations in Fiji (Viti Levu, the main island, and the Mamanuca Islands). Moreover, this study concentrates on the accommodation sector as the core component of the tourism product in Fiji. The paper is based, in part, on a more comprehensive report on climate change and tourism in Fiji ( Becken, 2004 ).

1.1. State of tourism in Fiji

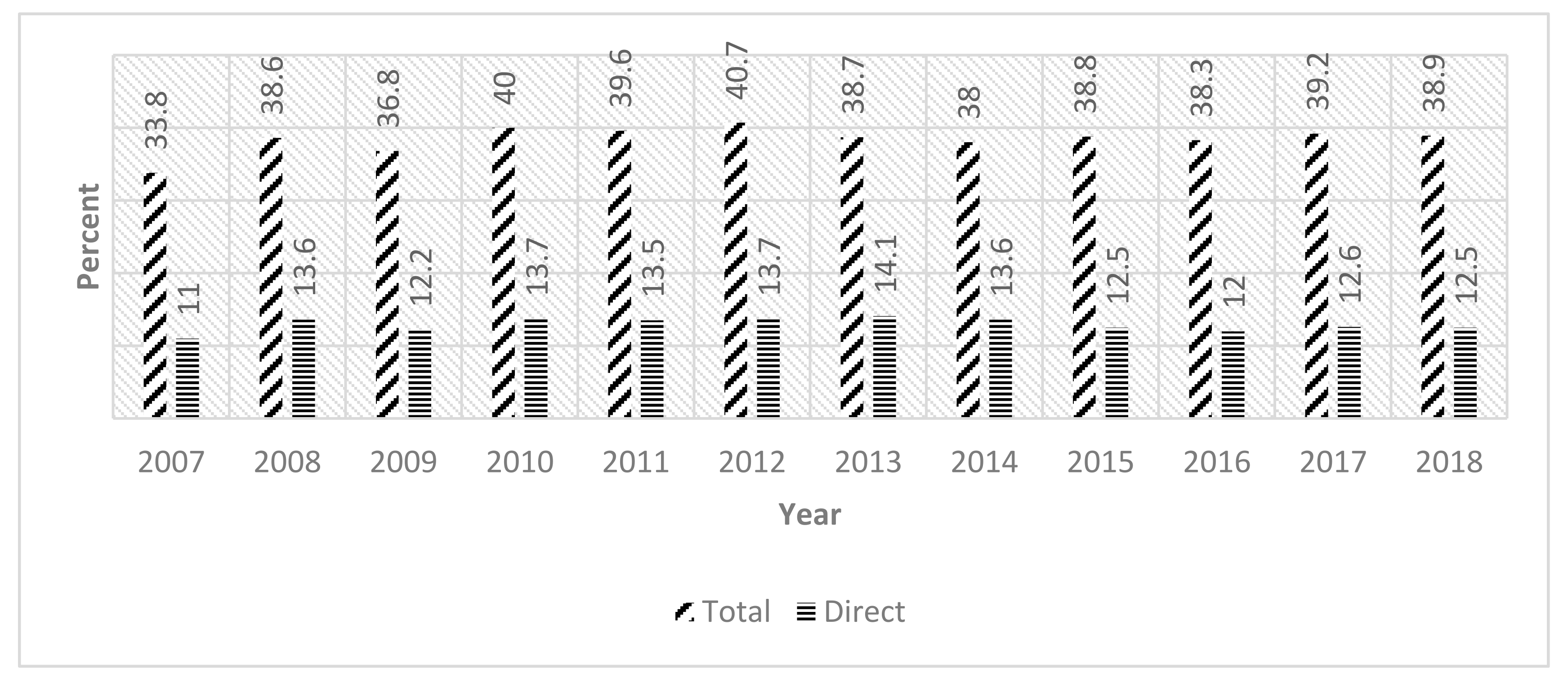

In 2002, about 400,000 tourists visited Fiji with an average length of stay of 8 days. Despite adverse political events nationally and internationally, tourism in Fiji has grown over the last years ( Fig. 1 ) and is forecast to grow at an average rate of 6.2% per year between 2004 and 2014 ( Campbell, 2004 ). In 2002, most tourists came from Australia (31%), New Zealand (17%), the United States (15%) and the United Kingdom (11%). While most visitors come for ‘rest and relaxation’ typically linked to beach environments ( Ministry of Tourism, 2003 ), current marketing campaigns aim to shift the image away from pure beach promotion to a wider experience. Also, there are attempts to attract more tourists from long-haul markets, for example from the USA and Europe, in addition to the traditional markets of Australia and New Zealand ( Ayala, 1995 ; S. Toganivalu, Manager, Fiji Visitors Bureau, pers. comm.).

International visitor arrivals to Fiji between 2000 and 2003.

Tourism is increasingly important to the national and local economies. In 1998, tourism earned F$568 million in foreign exchange, while sugar only earned F$244 million ( Narayan, 2000 ). The decline of the sugar industry ( Narayan and Prasad, 2003 ) has resulted in heightened expectations from tourism as the main export industry ( Levett and McNally, 2003 ). In 1999, tourism directly and indirectly contributed 29.5% to GDP and 37.0% to exports ( Word Travel and Tourism Council, 2001 ). A major problem of tourism in Fiji, however, is its economic leakage; about 60% of tourists’ expenditure is estimated to leak out of the country ( Levett and McNally, 2003 ).

Several attempts have been made to improve the environmental performance of Fiji's tourism industry, including projects related to energy efficiency and renewable energy sources, and environmentally friendly resort construction ( Aalbersberg et al., 2003 ). Nevertheless, the overall focus of the Government is on increasing visitor numbers, retaining tourist dollars, and encouraging further development ( Narayan and Prasad, 2003 ). The Fiji Tourism Development Plan 1998–2005 ( Ministry of Tourism, 1998 ) recommended a ‘Step Change’, with a substantial number of new developments, mainly in the already developed areas of the Coral Coast and the Mamanuca Islands. Levett and McNally (2003) assessed the sustainability of this Tourism Development Plan and concluded that it contains some useful suggestions for reducing tourism's environmental impacts. However, the authors expressed concern that the large scale of the envisaged development could exceed carrying capacities and ‘tip the balance’ towards irreversible effects on the environment. While there exist policy frameworks that regulate tourism development (e.g., Environmental Impact Assessment), few of them are implemented and work in practice.

1.2. Vulnerability of tourism in Fiji to climate change

Several studies on climate change, climate variability and vulnerability, and impact assessments have been undertaken in the South Pacific (e.g., Hay et al., 2003 ) and in Fiji specifically ( Nunn et al., 1994 ; Feresi et al., 2000 ; World Bank, 2000 ). Projected temperature increases are somewhat lower for Fiji than for the global average of 0.1 °C per decade ( IPCC, 2001 ), being in the order of 0.7–0.9 °C per 1.0 °C increase in temperature globally ( Feresi et al., 2000 ; Salinger, 2000 ). Sea level rise in Fiji may be in the order of 23–43 cm in 2050, and up to 1.03 m in 2100 ( World Bank, 2000 ). Trends in climate change and sea level rise due to global warming have to be seen against other variations caused by existing natural variability, prevailing winds, earth crustal movements, and wave action.

Most of Fiji's population (about 90%; Feresi et al., 2000 ) and infrastructure (e.g., towns, airports, resorts) are currently located on coastal and low-lying areas and, therefore, are potentially affected by inundation and other damage to coastal systems. However, in contrast to atoll islands (e.g., the Maldives or Kiribas), the higher Fiji islands such as Viti Levu offer some room to shift activities inland under a long-term scenario of sea level rise. Climate-related risks in coastal areas pose a risk for existing capital and could also be a major impediment to further investment and capital, in particular when insurance premiums are high or exclude cover for damage resulting from climate-related impacts. Other problems associated with rising sea levels, besides inundation, include flooding, intrusion of salt water into groundwater and rivers, and drainage problems ( Feresi et al., 2000 ).

Coastal retreat and erosion resulting from changing wind patterns and strength, changes in shoreline features (e.g., groynes and sea walls), and sea level variability and sea level rise are major problems, as they affect tourism building stocks and beaches. Coastal retreat over the last decades in Fiji may be in the order of 15–20 m in certain locations (Mimura and Nunn, 1994, in Feresi et al., 2000 ). Low-lying atolls could be completely lost as a result of sea level rise. In addition, major damage to existing coastal ecosystems is expected as a result of climate change ( World Bank, 2000 ). Coastal ecosystems are already under pressure from overexploitation, pollution (from sewage, toxic substances, and nutrients), deforestation, infrastructure development, loss of mangroves, 1 conversion into agricultural land, and coral mining ( Feresi et al., 2000 ). The cumulative effect of these non-climate-related impacts reduces the ability to cope with sea level rise and other adverse consequences of climate change.

There is great uncertainty about how climate change might affect the frequency and nature of extreme events, such as cyclones and floods. Climate models suggest, however, that the average intensity and possibly the frequency of cyclones may increase. Currently, on average, there are 1.28 cyclones per year in Fiji ( Feresi et al., 2000 ). Cyclone-related risks for tourism include loss of quality holiday time, disrupted transport, cancelled flights, stranded passengers, destroyed tourism infrastructure and overall damage to Fiji's image as a safe and attractive destination. The greatest damage is often associated with storm surges—large masses of water pushed onshore by tropical cyclones and potentially aggravated by astronomical tides. Under global warming conditions the risk of storm surges is increased as a result of higher sea levels and changes in cyclone characteristics ( McInnes et al., 2000 ).

Climate change entails changes in precipitation patterns with wide implications for soil moisture and water availability, and as a result agricultural production and water supply for households and tourism. Current climate models provide ambiguous projections regarding precipitation in Fiji, although there is some indication that heavy rainfall events might increase while total rainfall might decrease ( Hay et al., 2003 ). It is also possible that droughts may become more frequent, which would require water management measures to reduce the need for freshwater. Currently, loss from leakage from water pipes in Fiji is greater than potential decreases in water availability due to climate change ( World Bank, 2000 ).

Coral reefs are among the most threatened ecosystems in Fiji. Reefs have several functions: they are important for biodiversity, provide habitat for fish, buffer against waves and erosion, and provide carbonate sand for beaches ( Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2000 ). The optimal ambient temperature for coral is 25–29 °C and they are extremely sensitive to sudden changes in their environment. When corals are under stress, they expel the algae (dinoflagellates) that symbiotically supply them with oxygen or food, resulting in ‘bleaching’. Corals are already under stress from factors such as high nutrient content, turbidity and sedimentation, overfishing, destructive fishing methods, changed water chemistry and physical damage, and an increase in sea level. Some corals can grow at the same rate upwards as sea levels rise; however, these types of corals are not common in the Pacific, where existing coral species are characterised by lateral rather than vertical growth ( Nunn, 2000 ). An ecological shift in coral composition would be required in the Pacific to compensate for rising sea levels. Stress thresholds that result in bleaching events will become very frequent in islands of the South Pacific between 2010 and 2070, and it is likely that in the next 20–50 years corals as dominant organisms on reefs will disappear ( Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2000 ). Destruction of a substantial proportion of the coral reefs means that one of the major pull factors for tourists to Fiji could disappear (see also Cesar et al., 2003 ).