The Rise and Fall of Iceland’s Tourism Miracle

Andrew Sheivachman, Skift

September 11th, 2019 at 2:30 AM EDT

Life has changed for Icelanders as the country's tourism industry faces a slump. While many are looking at the change as an opportunity to reassess their business, the widespread decline of tourism across the country presents intractable problems.

Down in the icy tunnel, the glacier is sweating. A dozen tourists slip around in the dark, taking selfies and scooping water into bottles from slushy puddles whenever the guide stops walking. Water streams down in thick rivulets throughout, dousing everyone in frigid water.

At the Into the Glacier attraction in northern Iceland, the waves of rapacious tourists snapping up dirty water from a rapidly melting glacier is a stark reminder of the state of Iceland’s tourism sector.

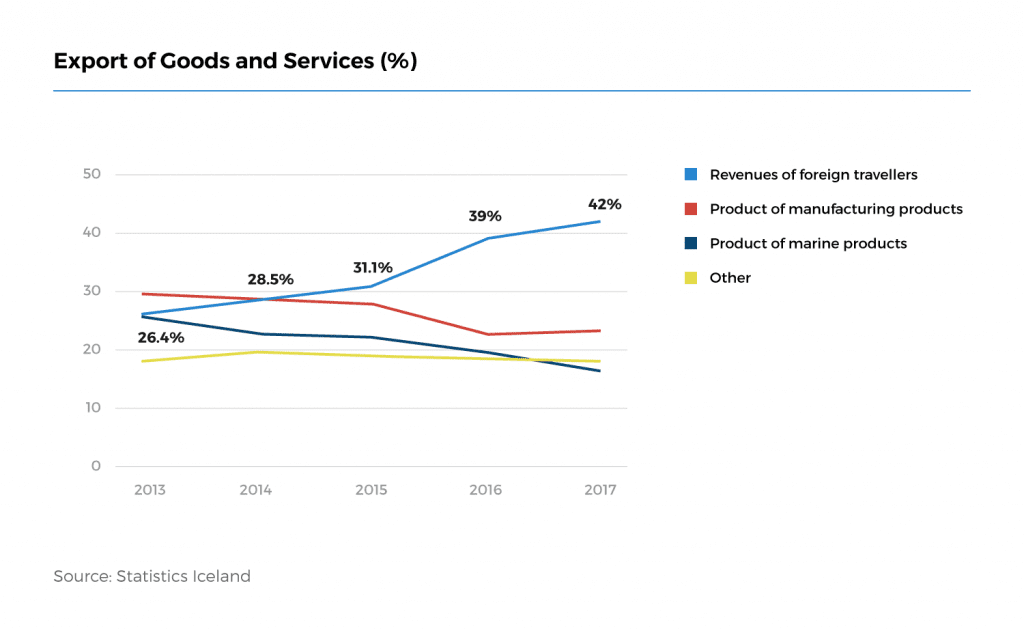

Iceland has been the poster child for the positive and negative effects of the overtourism phenomenon. Tourism growth helped the country recover after a brutal financial crisis and has empowered a new breed of entrepreneurs. Tourism revenue now accounts for 42 percent of Iceland’s economy, an increase from around 27 percent in 2013, according to Statistics Iceland.

With tourism taking on increased importance, the country’s fishing and manufacturing sectors have contracted over time. The change has made the country’s overall economy reliant on foreign visitors.

“It’s never been about the tourists, it’s more about the industry itself,” said Inga Hlín Pálsdóttir, director of Visit Iceland . “After the financial crisis, we were always worried. Are we going into the same bubble? Are we going in the same direction, that this is a bubble that is going to burst?”

Nearly a decade into Iceland’s unprecedented growth as a global tourism hotspot, a variety of issues have led to an economic slowdown that many, surprisingly, see as a good thing for the country’s travel sector.

As the wave of overtourism crested in Iceland over the summer, the country is looking for what’s next. Fortunes have been made and lost over the last decade, with many now looking to the future of Iceland as a more mature tourism destination. Skift returned after three years to Iceland in July, speaking to more than a dozen tourism leaders and residents about the country’s troubles and path forward.

What was different this time was a sense of concern for the country’s overheated tourism industry, What’s more, there is a worry about a malaise left in the wake of an unprecedented boom period that helped bring the country out of an economic recession. Instead of embracing tourism growth, nearly everyone said it is now time for the country to sit back and take stock of how tourism fits into a more sustainable overall economy for Iceland.

The city of Reykjavik remains dotted with cranes as new construction projects have blossomed in recent years. New international shopping outlets, like H&M, have invaded the city at the same time. Generic restaurants and boutiques have popped up, bringing with them new inauthentic locations for travelers to shop and eat.

Many expect these types of projects to be put on hold as the country’s business community grapples with a reality where tourism may not be a reliable cash cow. As Reykjavik has transformed itself into a modern international city, the rest of Iceland may have been left behind. With the lack of a serious cultural backlash against tourism, most have now realized just how crucial the travel sector is to Iceland’s future prospects.

Much in Iceland has changed since Skift visited three years ago. The attitude of Icelanders is now much more cautious, as the business people and small towns lifted up by tourism face the prospect of forging ahead with fewer visitors. Let’s look at how the country got to this point and how its tourism leaders are adapting despite deep uncertainty.

The Big Picture

To understand where Iceland stands today, it’s important to chart the last decade of the country’s evolution following a devastating financial crisis in 2008. Iceland had relied on heavy industries and fishing to power its economy, but over-leveraged banks helped lead to a dramatic drop in the value of the Icelandic krona and led to a rise in unemployment as the country had to be bailed out by the International Monetary Fund.

Tourism in Iceland began to grow following the April 2010 eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in the country’s south. It was cheap to visit and costs were affordable due to the country’s weak currency; the eruption acted as a global billboard for Iceland’s natural beauty.

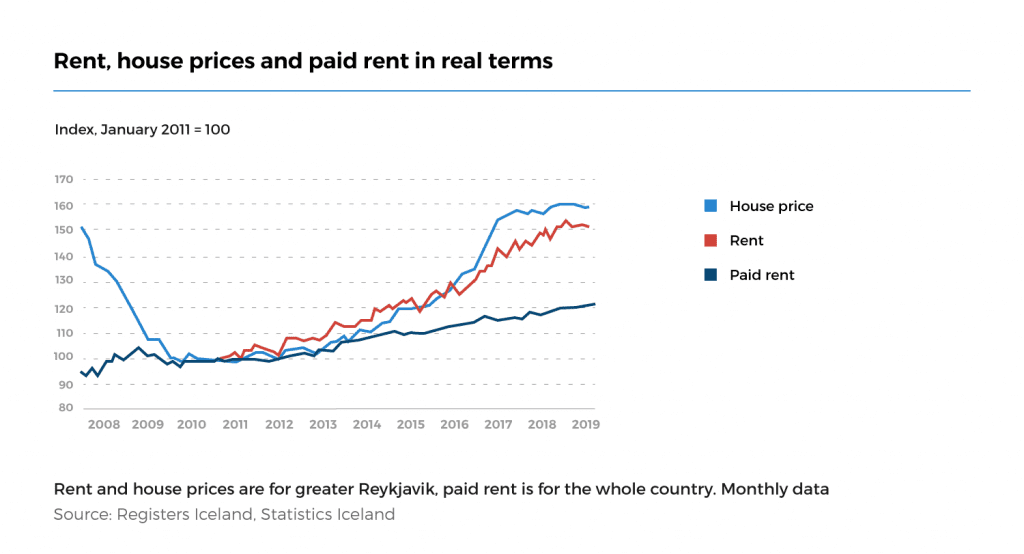

As time went on and its economy recovered, prices began to rise for residents and tourists alike. What was once an affordable vacation became pricier despite the cheap flights that continued to bring passengers to Iceland. Gas and food became pricier for Icelanders, too, putting pressure on households across the country.

“Iceland was in fashion, and the exchange rate of the krona was attractive from the UK, where the boost in tourism really started,” said Magnus Arni Skulason, chairman of Reykjavik Economics , a consulting group. “Tourists from the UK started it, then the U.S., then Germany and other European countries. Post-Brexit, there was a big impact on medium-income Brits who wanted to come to Iceland. And then the appreciation of the krona made it more expensive to come here.”

Now Iceland’s economy is in its first slump since its financial crisis began in 2008. The strong krona, the collapse of Wow Air, the Boeing 737 Max fiasco, and rising labor costs have each contributed to the current downturn.

“We were going down as well, regardless of Wow Air, and that was because the currency was too strong,” said Bjarnheiður Hallsdóttir, head of the Icelandic Travel Industry Association . “It was mainly that but it was a few things at the same time which caused this rather strong decline.”

It’s been a near perfect storm of factors that have led tourism growth numbers to fall and left many Icelanders wondering whether tourism is truly the answer for Iceland’s future. The unexpected collapse of Wow Air in late March helped kick off the massive decline in tourism; tens of thousands of passengers who were planning to visit Iceland on the cheap can simply no longer visit.

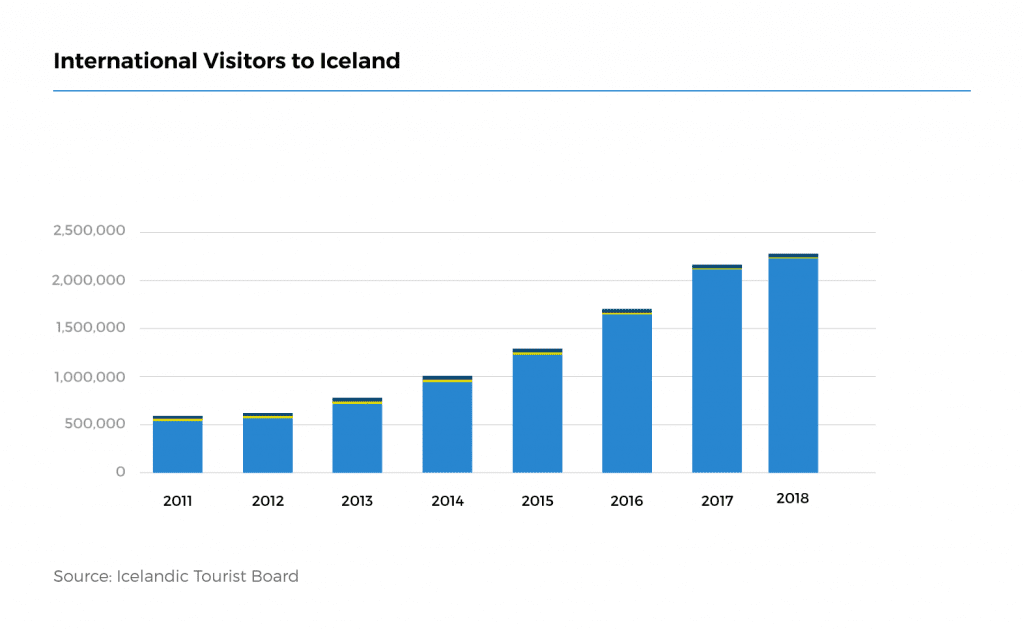

Statistics don’t bear out a catastrophic collapse of Iceland’s tourism sector. Far from it, in fact; tourism in 2019, so far, has fallen to 2017 levels, according to leaders across Iceland’s tourism sector judging by their businesses. The full picture won’t emerge until the end of the year, when Iceland enters the shoulder season for its tourism industry.

The latest tourism accounts from Statistics Iceland show what tourism executives have noticed in their own businesses. In June, the beginning of Iceland’s busiest traditional tourism period, tourist visitation dropped by 15 percent year-over-year. Tourism VAT turnover dropped 12 percent, mimicking the visitation drop.

To put a potential 15 percent decline into perspective, Iceland experienced 5.4 percent growth in international visitation in 2018 and 24.1 percent growth in 2017 according to the Iceland Tourist Board. So a 15 percent decline over the next year would bring visitation back to 2017 levels, which represents a 400 percent increase from 2011 visitation levels.

A few wrinkles emerge that show how the slowdown is affecting the types of vacations people are taking. Hotel stays were flat year-over-year in June, while Airbnb stays dropped 11 percent. Unpaid accommodations, like camping, declined a massive 30 percent, presenting more evidence that Iceland’s tourism economy is shifting away from affordability to a more expensive and upscale proposition for travelers.

Iceland’s hotel sector has been built up during the boom, growing 9 percent in number of rooms from July 2014 to July 2019, according to STR . Seven hotels totaling another 1,129 rooms are in the country’s pipeline, and many in the tourism sector are concerned those properties will be shelved if economy uncertainty persists. Strong regulations against Airbnb, limiting rentals to 90 days each year, have also decreased the ability of travelers to use homesharing services.

Still, housing in Reykjavik remains incredibly more expensive than elsewhere in the country.

The flip side is that tourism’s growth outside of the Reykjavik area, which has helped revitalize sleepy towns and empowered entrepreneurs to build businesses, is perhaps most severely affected by this slowdown.

Vehicle traffic around Iceland’s ring road has decreased across all of the country’s regions, with East and West Iceland seeing double-digit year-over-year declines in July. All those remote villages and fishing towns which rode the wave of increased tourism are now feeling the effect of fewer visitors during the peak summer travel season.

“In a way this growth was unexpected and then too much,” said Hallsdóttir. “But on the other hand, we have a lot of new investment and new companies which are suffering right now because of that. For the long term thinking, it’s good that we have a little break now regarding the tourism infrastructure. And then I’m talking about the public sector. The private sector is ready and was ready when the big boom came, but the public sector wasn’t.”

Air Trouble

While the collapse of Wow Air helped touch off the downturn, the struggles of national carrier Icelandair over the last year bear some responsibility as well.

Wow Air, the low-cost carrier launched by entrepreneur Skúli Mogensen in 2012, eventually grew to a 20 plane fleet before economic trouble hit in 2018. New widebody planes increased its operating costs and the airline had trouble filling the extra seats on these planes. The airline began to lose money before collapsing into bankruptcy on March 28, 2019 following a failed acquisition by Icelandair .

The collapse immediately made it more difficult and expensive for U.S. travelers, who account for about a third of total visitors to Iceland, to visit this year. High costs already deterred U.S. visitors with 7.1 percent fewer visiting from August 2018 to July 2019 than in the previous year.

Chinese visitors continued to surge 14.8 percent over the same period while top European destinations except for Poland declined. Chinese visitors also spend the most of any traveler, likely helping stanch some of the bleeding from the widespread decline in tourism.

At the same time, rival Icelandair was beset by its own problems. It was forced to lease aircraft after grounding its fleet of nine Boeing 737 Max aircraft, leading to a decline in capacity and increased costs as the summer travel season began. Strong competition from European carriers also limited its ability to grow airfares in 2018, causing it to lose money.

It sold off 80 percent of its Icelandair Hotels division to Malaysian investor Vincent Tan as part of a plan to focus solely on air transportation and tourism operations.

“The MAX aircraft were intended to cover 27 percent of Icelandair’s passenger capacity in 2019,” said Icelandair CEO Bogi Nils Bogason in a recent earnings report.” For this reason, the position in which the company now finds itself as a result of the suspension of the MAX aircraft is without any precedent and has a significant impact on the operations and performance of the Company… We have also placed emphasis on ensuring seating capacity to and from Iceland, with the result that the number of Icelandair’s passengers traveling to Iceland has increased by 39 percent in the second quarter compared to the same period last year.”

The loss of Wow Air, then, has helped to boost the future prospects of Icelandair once the Boeing 737 Max situation is sorted out.

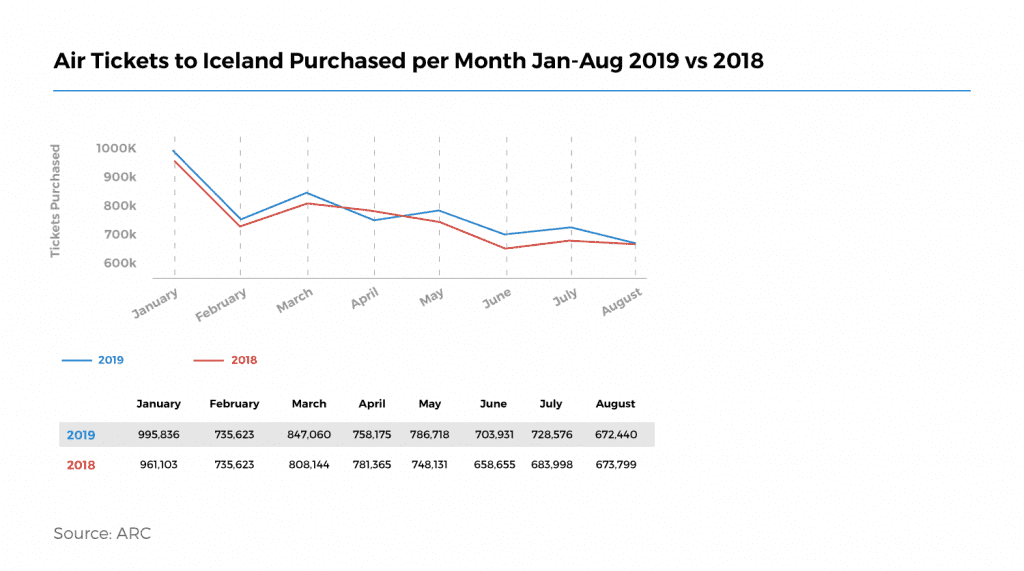

The growth of both airlines essentially eliminated seasonality for Iceland’s tourism industry, and a lasting disruption is likely to bring it back in a major blow to the sector’s less established players. An analysis by Airlines Reporting Corp., which provides services to most global passenger airlines, found that its partner airlines have actually sold more tickets to Iceland in 2019 than 2018, presenting some hope that the downturn will be limited in scope.

“Both Icelandair and Wow Air were adding seat capacity during the winter,” said Sveinbjörn Indridrason, managing director of Isavia , Iceland’s airport authority. “Last year there was no seasonality in Iceland. So you had this summer traffic three months, these shoulders four months and then the winter traffic five months. Similar distribution passenger-wise, not per passenger. So the seasonality just went out of the Iceland market.”

Sveinbjörn Indridrason

A side effect of the decline in flights has been the limited ability for Icelandic goods to reach global markets, injuring economic sectors outside of tourism in the process. International cargo shipping has increased from 35.2 million tons in 2010 to 57.4 million tons in 2018, broadening the ability of Icelandic companies to sell goods in foreign markets.

For what it’s worth, the hub strategy which helped power the growth of aviation in Iceland is still being pursued by Isavia. While the company’s master plan from 2015 did not anticipate the massive surge in new routes and arrivals, this downturn is helping to bring the sector back to its original projections.

“When Wow Air went bankrupt it was not bad timing if you look at it from a construction perspective,” he said. “So we are not in the middle of any real construction so we don’t have to lay down any hammers and have like a half-built terminal building with a lot of invested costs but maybe not the revenues to finish it.”

Indridrason confirmed that he had been contacted by representatives of WAB Air, which had designs to restart Wow Air’s operations in the near future as an Icelandic company, and American investor Michelle Ballarin who purchased Wow Air’s assets following the bankruptcy. In early September, Ballarin announced her plans for Wow Air to begin service once again over the next year although experts are unsure of how realistic her timetable is.

“There’s a reason Wow Air failed the first time,” said Jay Shabat, senior analyst at Skift Airline Weekly . “There was simply too much capacity in the market and what’s known of the plan to revive it doesn’t inspire much confidence.”

There have also been rumblings of the potential for a new international airport near Keflavik to help supercharge tourism growth and the country’s cargo business. It’s a thorny political issue, but Indridrason noted there would be many challenges faced by operating two busy airports so close to each other.

Even if the government wanted to close Keflavik and operate a single international airport, the U.S. Navy’s base at the airport complicates the matter.

Perhaps the biggest opportunity to grow tourism would be through a more robust network of regional airports across the country. Right now, tourists are forced to transfer from Keflavik to Reykjavik City Airport, nearly an hour away, in order to fly into one of Iceland’s smaller domestic airports.

Many proponents of increased tourism across Iceland believe an increase in domestic flights from Keflavik would help boost the industry as it spreads across the country. Right now, direct flights are available for tourists from Keflavik to Akureyri in Northern Iceland but not to other areas. Besides occasional charter flights direct from international destinations that already happen, a more robust series of routes and airports have the potential to boost future growth.

“If you need to build infrastructure that can handle serious international traffic [in these smaller regions], it would be very costly and will probably never be profitable,” said Indridrason. “The domestic airport system, it’s a public transportation system funded by the State of Iceland. And public transportation always needs to be funded by the municipalities or the individual States. But you can’t combine those things if you don’t bring [travelers first to boost the economies in those regions].”

Tour Operator Woes

Part of the problem is that many emerging tourism companies acted to take advantage of the boom by growing quickly instead of taking a more measured and conservative approach.

Travelers are still spending on package tours when they visit, despite flights and accommodations eating up a more significant portion of travelers’ budgets, according to data from the Iceland Tourist Board.

While travelers continue to spend, the margins operators are likely to have shrunk.

“Wow Air went down in April, and that obviously had an effect,” said Hjalti Baldursson, CEO of Reykjavik-based tour operator technology company Bokun , which is owned by TripAdvisor and operates the technology backbone for most tour companies in Iceland. “There was a small decrease in May. April was 1 percent up year-on-year, but other months are up significantly in terms of booking numbers. That doesn’t tell the story of whether the companies profitable, because if you look at the average order value measured in dollars that is going down quite significantly. This has to do with currency fluctuations between the Icelandic króna and the U.S. dollar.

“The margin of the companies that are selling is going down. On top of this, there is big competition in Iceland. There are more and more companies coming into the market that are providing good products.”

Bokun’s data also show an increase in direct online booking, meaning operators pocket more of a booking’s value, increasing the margins on their products in the process. The cost of labor, though, presents a major challenge to tour operators operating on thing margins.

“Another thing influencing companies in Iceland is that salary costs are going up,” said Baldursson. “Iceland has been coming off its own success, the economic metrics of the country are extremely good. It’s a very healthy economy and in all measurements a rich country. So getting staff and competing with lower paid staff in other markets is becoming harder and harder.”

Evidence backs this claim up. Iceland has the fifth highest gross domestic product per capita among European countries, and the country’s wages increased 6.7 percent from 2016 to 2018. The country’s strongest unions also recently locked in a wage increase, putting more pressure on low-margin businesses. Even with seasonal workers from other European countries working during peak periods, the cost of labor remains a major obstacle to growth.

The economic contraction is leading to a wave of consolidation in Iceland’s tour industry. On Skift’s last trip to Iceland three years ago, we spoke to Hjörvar Sæberg Högnason, who had founded tour operator Reykjavik Sightseeing in order to appeal to the new wave of international visitors to Iceland.

Hjörvar Sæberg Högnason

Since then a race to the bottom on pricing coupled with rising labor costs and the high value of the krona have caught up to Högnason. Competition with the established Gray Line Iceland and Reykjavik Expeditions , the other two major bus tour operators in Reykjavik, had led the company down an unsustainable path once signs of a tourism slowdown began to emerge late last year.

An effort to grow his business by partnering with Blue Lagoon for the spa’s shuttles, and earning the concession for Keflavik’s city shuttle to Reykjavik, also proved challenging with respect to low margins and the complications of running a bus tour operation alongside shuttles.

In an effort to compete going forward, Gray Line Iceland and Högnason’s Reykjavik Sightseeing announced a merger earlier this year to provide a competitive advantage against Reykjavik Expeditions.

“There’s increasing talk of companies needing to merge,” said Högnason. “We’re nowhere near a catastrophe; the situation gives us the time to step back and run our businesses in a more economic fashion.”

He also noted that self-guided tours and the ease of renting a car likely contributed to a downturn in business for bus tour operators. A recent report suggests 80 percent of visitors to Iceland rent a car at some point in their trip .

“Year-round, we think there will be more car rentals on the road,” said Högnason. “You have all the international car rental brands and local ones; I’d imagine they are in a bidding war for travelers right now.”

In the rush to compete over the last three years, money was invested in growing his fleet and branding at the expense of innovating in the actual tour experience. Finding skilled, qualified guides remains a challenge particularly as Iceland’s tourism sector continues to mature.

“We need to do it extra well, in a way that makes people excited to come back the next day,” said Högnason. “The agenda is to teach travelers how to behave and embrace the traveler experience. There is decreasing demand, so let’s make sure they leave with a positive impression.”

North American tourists explore downtown Reykjavik. (Andrew Sheivachman / Skift)

Much like Wow Air couldn’t survive a blip in demand after a potential merger with Icelandair was tabled, so too are tourism companies consolidating in order to better weather this uncertain period. A return to strong growth instead of the explosive growth the country has seen this decade will ensure that business practices shift and become less risky for operators and their employees.

“It is quite easy to run a company if your business is growing 50 percent,” said Baldursson. “Then you’re typically worried for the customers and not the operational efficiencies. Now when we’re seeing small double digit growth, maybe, as for example, in July we saw a 15 percent growth, in June we saw a 7 percent growth in number of bookings. We’re seeing that companies have a tendency now to look more into their costs and cost base. It’s an opportunity for them, and I think it’s a healthy revamp of their operations that they’re running through right now.”

Another wrinkle could spell future trouble for Iceland’s tour sector: the quiet rise of cruising in ports across Iceland. Overall, the number of cruise ships entering port has increased from 476 in 2016 to 750 in 2018, according to Cruise Iceland. Passengers arriving in port grew from 326,850 to 441,789 over the same period, a 35 percent increase in the number of potential visitors to Iceland’s port cities.

Cruise passengers tend to cause congestion at a city’s most popular attractions without contributing much to the local economy.

The biggest beneficiaries have been not just Reykjavik, but the smaller cities across the country that see few international visitors from tours and domestic flights. With the high costs associated with a trip to Iceland expected to remain, a more affordable cruise vacation is becoming a compelling option for vacationers.

“Above all the ports are happy about it,” said Hallsdóttir, head of the Icelandic Travel Industry Association. “Some of the smaller communities in the rural areas very far away from Reykjavík, they are getting some business at least. This is a topic we have to really have to think about and regulate before it gets over our heads.”

Something for Everyone

As a tourism hotspot matures, it tends to lose some of the authenticity that made it attractive to visit in the first place. Iceland, too, with its ample natural beauty and unique culture isn’t immune to the forces of globalization, as evinced by the transformation of Reykjavik into something resembling a traditional international city.

As investment dollars have flowed into tourism, new attractions have been under development that wouldn’t be out of place in any major travel destination around the world. The difference is that these attractions are being designed for not just travelers, but native Icelanders as well.

One example is Perlan , a landmark overlooking Reykjavik which has been converted into a museum and restaurant with stunning views of the city. A dome built around six water tanks, the building used to house a rotating restaurant on its top floor. Today, the building attracts visitors during the week and Icelanders on the weekends.

By appealing to locals instead of just tourists, the somewhat strange attraction has found new life in an Iceland where the new can coexist with the old.

“Flying is now more expensive, and accommodations are more expensive; Southern hotels aren’t fully booked,” said Eva Björnsdóttir, the reception manager at Perlan, of the country’s prospects amid a tourism decline. “Icelanders need to come together and help each others’ businesses. We need to make sure that travelers have a good time, not just in one place, but across their entire trip. They’re competing for the same guest. We need to think of Iceland as a whole experience for travelers.”

Another newcomer to Reykjavik is FlyOver Iceland , a mixed media experience where visitors go on a virtual flyover around Iceland’s most scenic landmarks.

On a hard-hat tour of the attraction in the final stages of construction, it was clear Flyover Iceland could exist in any major tourist destination; the concept, created by the Canadian company Pursuit, already has similar operations in Toronto and Las Vegas.

“A lot has happened in the tourism sector over the last year,” said Eva Eiríksdóttir, manager of marketing and brand experience for FlyOver Iceland. “It has cooled down and people were panicking, but the slow down is probably a good thing.”

Eiríksdóttir pointed out that the weather is often bad in Iceland, increasing the demand for indoor activities like FlyOver Iceland for visiting families and residents. With high property values and rent prices in downtown Reykjavik as well, new attractions could provide the impetus for the development of new neighborhoods and communities too.

These types of attractions aren’t just popping up in Reykjavik, though. New spas, attractions, and experiences are popping up in the country’s North and South regions, offering a blend of Icelandic culture and modern convenience. One of the most absurd is 1238: The Battle for Iceland, a virtual reality experience that puts visitors inside a variety of historical viking battles.

The attraction is located in Skagafjörður, which sits about 3 hours by car from Reykjavik and 90 minutes from secondary city Akureyri, showing how regions outside Iceland’s capital have benefitted from the tourism boom.

Instagram and Its Discontents

Speaking with tourism experts and locals alike, concerns about the damaging effects of increased tourism on Iceland’s environment were minimal.

Iceland is a victim of climate change like so many places but has chosen to focus on sustainability in the areas it can control, like traveler behavior and waste management. A major campaign to encourage visitors to drink tap water instead of bottled water, for instance, has found success this year as news of the demise of Icelandic glacier Okjokull entered global headlines.

Tourists prepare to enter a glacier in outside of Husafell, Iceland. (Andrew Sheivachman / Skift)

Specific cases of overtourism, though, gravely concern many who have tired of people exploiting the environment for profit.

Many tie the rise of social media to the growth of Iceland’s tourism sector in an integral way, and it’s difficult to see a way out.

“There’s an issue with locations and the number of people visiting them,” said Joe Shutter, a Reykjavik-based photographer who leads small group photography tours across the country. “You can have a well behaved visitor and a not very well behaved visitor. They both have two feet. There is a certain critical mass. There’s a scale transformation that takes place. Location A: 10 people visit. Location B: 100 people visit. The damage is more than ten times worse on location B. Damage goes up exponentially. Some places literally cannot handle it.”

He gave an example of an Instagram influencer who had recently posted specific information for travelers to visit a remote and beautiful location he shoots at, replete with geotag information. When he asked the influencer to remove the geotag, the influencer simply said it would violate their ethics to do so and updated their caption with a warning for travelers not to litter or damage the location.

“This is the absolute lowest common denominator of how anybody should behave with a modicum of decorum in a location,” said Shutter. “I explained to them that two feet are two feet. And a hundred feet are worse than ten. And that a scale transformation takes place with that and that means that behaviors have to be modified in that sense in that certain places literally can’t handle that.”

Others say it should be up to the government to select specific places to protect instead of residents working to limit what areas that tourists can access. The Icelandic government has some of the strongest sustainability standards in Europe, but has been hands off when it comes to limiting where tourists can visit.

“If it’s a natural site and it has to be protected then there has to be a protection put on that area and with that comes regulation,” said Katarzyna Maria Dygul, who works with Visit Iceland on public relations and social media. “You can also put a quota on that, like you have all around the world a quota of how many people can visit a location because of that. Or when there’s vegetation, then the local authorities also have to understand that with the growing number of people they will have to adjust. People will not be able to go all the way on that vegetation but instead there will be a viewing patio or platform. That’s fine because… half a year later, other people who come will never expect to go on the grass. They will expect to stand on the platform.”

Dygul and Shutter are co-owners of The Space , a co-working space and art studio in downtown Reykjavik that wouldn’t be out of place in Berlin or Brooklyn.

This tension was also present during Skift’s earlier trip to Iceland. Many who are concerned about the effect of increased tourism on the environment and roads, for instance, also believe that increased fees or restrictions will drive away the travelers the country needs to continue its strong tourism growth.

An Icelander takes a smoke break in downtown Reykjavik. (Andrew Sheivachman / Skift)

It’s one thing, though, to appeal to the individual values or ethics of the individual traveler and encourage them to drink tap water or avoid driving their truck off a cliff. It’s another to curb the damage caused by social media’s herd mentality.

“The big group of people who come here are millennials,” said Dygul. “This is a group generally that is more empowered to do things on their own. We work with influencers all the time and it’s very easy to filter out those people who maybe have a large following and stunning content but basically the same content as everybody else… when you have another few hundred thousand people that do not know anything about photography but they want to take the same picture, you’re suddenly in a very different dilemma.”

The line between being a beneficiary or a victim of social media is slim in the age of overtourism. With Iceland’s tourism growth in doubt, it’s possible that the need to attract tourists will outweigh calls to limit tourism and its damage to the environment.

Others, though, have a more conservative vision for the future of tourism in Iceland. In the town of Húsafell, about 90 minutes from Reykjavik, sustainability and hospitality merge in a manner that attracts both international tourists and Icelandic families.

The small town is a destination for Icelanders looking to camp, and the family which owns the town built Hotel Húsafell to cater to the growing cadre of international tourists in 2015. The town also operates as a jumping off point for glacier and lava cave tours. There’s no Instagram bait, save for the mountains in the distance where Icelandic strongman competitions once took place.

The small hotel is popular with families and groups who tend to stay for just a day or two on their vacation, according to Kristján Guðmundsson, marketing manager for Hotel Húsafell. China is a major source market. During slow periods and the shoulder season, the property offers Icelander-only rates to increase demand. The small stature of the hotel, and popularity of Húsafell as a camping destination, make it less likely to be severely impacted by reduced tourism demand.

The hotel and the entire town is powered by sustainable geothermal energy, as well, with food from local fisheries and farms. The ownership is considering building a spa for international visitors, and is currently building a bath in a perilous, but scenic, valley nearby.

Húsafell is just one example of many Icelandic towns that have taken a more measured approach to profiting off the tourism boom. Those who grew more slowly during the boom years seem better positioned to survive the current downturn.

Uncertain Times

In many ways, it is likely a slowdown in tourism will help Iceland’s tourism industry become not just more stable, but more sustainable. While the future of Iceland’s tourism sector remains murky, the bottom hasn’t fallen in the first few months of the downturn.

It may be time for the Icelandic government to finally make a concerted effort to prepare for Iceland’s future as a beacon for tourists, particularly if its other industries continue to struggle. With limited growth expected from its flagging fishing and manufacturing sectors, leaders need to articulate a vision for the country that goes beyond becoming more hospitable to foreign guests .

The lack of a major backlash against tourism has led to the lack of a cohesive government policy to oversee its growth. There is something of a vocal minority, as one source put it, but those people are simply annoyed at seeing more tour buses and rental cars driving by their farms.

“The government is going to finish a new tourism strategy,” said Hlín Pálsdóttir, director of Visit Iceland. “Like probably everywhere else in the world, the main focus is on sustainability. How can we be sustainable? Because what has not been that much discussed is how important tourism has been for the regions. Many people are actually moving back to their hometowns, And they didn’t really have that opportunity a few years back.”

The good news for environmentalists and those concerned with the environmental impact that overtourism has had on Iceland is that the slowdown will reduce the effect of tourism in the short term. It may limit domestic investment in the country’s tourism infrastructure, though.

“Some of the tourism sites need more investment; we have to regulate the traffic, the tourism flow in certain areas,” said Hallsdóttir, head of the Icelandic Travel Industry Association. “There has been a lot more consciousness from the public sector in the last two, three years. They know now what they have to do and are willing to do it. So I think we will cope. That’s my strong belief… We are hoping to get in line with the normal growth, which is about 4 or 5 percent per year. Not these crazy numbers from a few years ago.”

With tourism growth tailing off, Iceland needs to look to the future. Relying on tourists to boost its economy worked for nearly a decade, but leaders need to search for methods to build a more stable environment for workers and entrepreneurs.

Tourism is an export that is highly susceptible to shifts in both supply and demand. With a global recession likely on the way in coming years, even a quick recovery for Iceland’s tourism industry may leave its overall economy in a rut should global tourism decline.

Perhaps the lesson from the end to Iceland’s tourism boom extends beyond tourism itself: it’s time to take action during a crisis instead of waiting for another miracle.

The Daily Newsletter

Our daily coverage of the global travel industry. Written by editors and analysts from across Skift’s brands.

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch

Tags: deep dives , iceland , overtourism

Photo credit: The Blue Lagoon in Grindavik, Iceland. Chris Ford / Flickr

Tourism in Iceland

Development of the tourism sector in iceland from 1995 to 2021.

Revenues from tourism

All data for Iceland in detail

Business Sectors

Environment, inhabitants.

- Municipalities and urban nuclei

- Internal migration

- External migration

- Marriages and divorces

Births and deaths

- Population projections

- Census - Overview

- Census 1981

- Census 2011

- Census 2021

- Elections overview

- General elections

- Local government elections

- Presedential elections

Labour market

- Labour force survey

- Labour force – register data

- Job vacancies

Wages and income

Social affairs.

- Social protection expenditure

- Municipal social services

- Social insurances

- Pension beneficiaries

- Women and men

Quality of life

- Household finances

- Liabilities and assets

- Household expenditure

- Material deprivation

- Economy and health

- Health interview survey

- Lifestyle and health

- Education - overview

- Pre-primary schools

- Compulsory school

- Upper secondary schools

- Universities

- Lifelong learning

- Educational attainment

- Sound recordings

- Religious organisations

- Associations

- Economic measures

- Enterprises

- Structural business statistics

- Insolvencies

- Labour cost

- Accommodation

- Short term indicators in tourism

- Travel survey

- Tourism satellite accounts

- Export of marine products

- Landings of foreign vessels

- Fish products, price indices

- Financial accounts of fisheries

- Fishing vessels

- Aquaculture

Agriculture

- Live stock and field crops

- Fertilizers

- Farm structure survey

- Financial accounts of agriculture

- Building cost index

- Constructions

- Manufacturing

Science and technology

- Community innovation

- ICT usage in enterprises

- ICT usage by individuals

- Telecommunication

- Consumer price index

- Producer price index

External trade

- Trade in goods

- Trade in services

- Trade in goods and services

Public finance

- General government

- Central government

- Local government

- Social security funds

- Social protection

- Educational expenditure

- Health expenditure

Employment and labour productivity

- Labour productivity

- Economic forecast

National accounts

- Gross domestic product

- Consumption expenditure

- Gross fixed capital formation

- Production approach

- Sector accounts

- Financial accounts

- Short term indicators

- Pension entitlements

Land and air

- Air quality

Air emissions

- Greenhouse gas emissions from Iceland (NIR)

- Greenhouse gas emissions from the economy (AEA)

- Emission of air pollutants (LRTAP)

Material flow

- Waste statistics

- Water consumption and water treatment

- Material flow accounts (MFA)

Green economy

- Environmental taxes

- Energy prices

- Production and consumption

- Energy flow accounts (PEFA)

- Public transportation

Contribution of tourism to GDP decreases by half

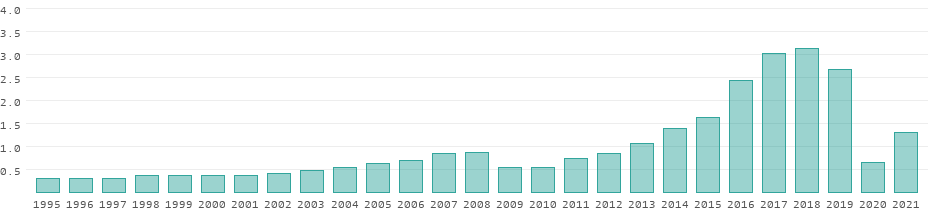

Preliminary results of the Tourism Satellite Accounts (TSAs) indicate that tourism as a proportion of GDP amounted to 3.9% in 2020 compared with 8% in 2019. Total internal tourism expenditure, inbound and domestic, amounted to 220 billion ISK in 2020, a decrease of 58% compared with 2019. Inbound tourism trips to Iceland in 2020 decreased by 81% from the previous year.

Tourism Satellite Accounts are produced by Statistics Iceland in order to calculate the contribution of tourism to the Icelandic economy, based on international standards in tourism statistics. TSAs highlight tourism within the national accounting framework and cover both inbound tourism and domestic tourism in Iceland.

Statistics Iceland now publishes for the first time statistics on employment in tourism based on international national accounts standards. Employment in tourism, presented here, is therefore new and not revised previously published statistics. A detailed discussion of results and a comparison of different methodologies for estimating hours worked can be found in a Statistics Iceland’s publication from 2018.

Domestic tourism expenditure amounted to 56% of total internal tourism expenditure Domestic tourism expenditure amounted to 122 billion ISK according to preliminary figures, a decrease of 14% from the year 2019. The share of domestic tourism expenditure of total internal tourism expenditure in 2020 was 56%, compared with only 27% in 2019 and hasn’t been higher from the start of the time-series in 2009. The largest share of domestic tourism expenditure in 2020 was towards accommodation, a rise of 18% compared with 2019. A close to 32% increase was measured in expenditure towards food and beverage services in 2020, compared with the previous year. The number of overnights by domestic tourists increased by 40% during the same period.

Inbound tourism expenditure decreased by 75% Inbound tourism expenditures amounted to 98 billion ISK in 2020, according to preliminary figures, and decreased by 75% compared with the previous year’s expenditure. The largest share of inbound tourism expenditure in 2020 was on accommodation but decreased by almost 76% compared with 2019.

The total number of inbound tourism trips to Iceland was 490 thousand in 2020 and fell by 81% compared with 2019. Tourists travelling to Iceland were primarily overnight visitors arriving by scheduled air transportation. The number of overnight visitors decreased by 76% in 2020 compared with 2019, and the number of overnights decreased by 75%.

Tourism proportion of GDP compared with other industries in 2020 In 2019, tourism was the third largest industry, by contribution to GDP, but plays a less significant role in 2020. When comparing tourism to other industries’ contributions to GDP, one must bear in mind that tourism is not classified as a separate activity in standard industrial classifications. Tourism as an industry is therefore assembled from a proportion of activities of multiple other industries.

Employment in tourism The number of employed persons in tourism fell by 31% in 2020 compared with 2019, but close to 21,000 people were employed in jobs related to tourism in 2020 compared with 30,800 people in 2019. Total hours worked in tourism decreased by 39%, from 41.2 million working hours in 2019 to 25.3 million working hours in 2020.

The tourism related industries that suffered the largest proportional drop in the number of employed persons were travel agencies, road passenger transport and accommodation. The number of employed persons in accommodation decreased by 2,500, or by 36%, from 2019. Close to 1,700 fewer people were employed in food and beverage services, 1,500 in air passenger transport and 2,000 fewer in travel agencies in 2020 compared with 2019.

A government measure that enabled entitlement to unemployment benefits alongside reduced employment ratio was available to companies due to the economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. According to experimental statistics published by Statistics Iceland on January 18, 2020 , the number of people that received the part-time unemployment benefits in the tourism industry in 2020 was around 13,800, out of the 21,000 employed. Thereof 3,800 were employed in accommodation services, 4,000 in food and beverage services, 2,800 in air passenger transport and about 1,600 at travel agencies. Accommodation and air passenger transport had the highest ratio, over 90%, of employees that accepted the part-time benefits.

Revised figures In parallel to the publication of the results of the TSAs for 2020, the results of the previous years have been revised. As TSAs belong to the central framework of the national accounts and are based on the results of the national accounts’ expenditure approach as well as the production approach, it should be emphasized that revisions made to those results also affect the TSAs.

Due to the TSAs being an economic series, the results have also been made available under economic statistics while remaining a part of the tourism category under business sector statistics. Users who already use Statistics Iceland‘s API service will need to update their connections. Connections providing the old version of data will remain active until 1 September.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Email article

Further Information

- Statistics / Population

- Talnaefni / Population / Population projections

- Talnaefni / Population / Family

- Talnaefni / Population / Elections

- Talnaefni / Population / Inhabitants

- Talnaefni / Population / Births and deaths

- Talnaefni / Population / Migration

- Talnaefni / Population / Census

- Statistics / Society

- Talnaefni / Society / Labour market

- Talnaefni / Society / Education

- Talnaefni / Society / Quality of life

- Talnaefni / Society / Culture

- Talnaefni / Society / Justice

- Talnaefni / Society / Wages and income

- Talnaefni / Society / Health

- Talnaefni / Society / Media

- Talnaefni / Society / Social affairs

- Statistics / Business Sectors

- Talnaefni / Business Sectors / Enterprises

- Talnaefni / Business Sectors / Fisheries

- Talnaefni / Business Sectors / Agriculture

- Talnaefni / Business Sectors / Science and technology

- Talnaefni / Business Sectors / Tourism

- Talnaefni / Business Sectors / Industry

- Statistics / Economy

- Talnaefni / Economy / Prices

- Talnaefni / Economy / Public finance

- Talnaefni / Economy / Employment and labour productivity

- Talnaefni / Economy / National accounts

- Talnaefni / Economy / External trade

- Talnaefni / Economy / Economic forecast

- Statistics / Environment

- Talnaefni / Environment / Land and air

- Talnaefni / Environment / Material flow

- Talnaefni / Environment / Energy

- Talnaefni / Environment / Transport

- Talnaefni / Environment / Air emissions

- Talnaefni / Environment / Green economy

- About Statistics Iceland

- Laws and regulations

- Rules for handling confidential data

- Act on the Consumer Price Index

- Act on the Wage Index

- Cooperation with users

- International cooperation

- Statistics Iceland policies

- Quality and security policy

- Revision policy

- Environmental and climate policy

- Privacy policy

- Communication policy

- Rules on statistical releases

- News subscription

- Tailored statistics

- Data for scientific research

- Publications

- Experimental statistics

- Foreign trade in goods - ex

- Deaths - ex

- Consumption of foreign tourists - ex

- Insolvencies and activity of companies - ex

- Overnight stays in hotels – ex

- First time owners - ex

- Young people in Iceland 2005-2018 - ex

- AEA from Iceland - ex

- Fuel sales - ex

- Impact of Covid-19 on cultural industries – ex

- Educational mismatch rate - ex

- Taxable payments - ex

- Economic measures in response to Covid-19 - ex

- Household work-tt

- Skills supply and demand - ex

- Food flow through Iceland's economy- ex

- Public grants in the cultural and creative industries

- News Archive

- Advance release calendar

- Learning statistics

- Statistical database

- Methods, quality and classifications

- Classifications

- Methodological papers

- International guidelines and definitions

- Journal and conference papers

- Older publications

- Icelandic Historical Statistics

- Iceland in figures 2018

- Statistical Yearbook of Iceland 2015

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Search ITA Search

- Market Overview

- Market Challenges

- Market Opportunities

- Market Entry Strategy

- Agriculture - Food and Beverage

- Consumer Goods and Entertainment

- Data Centers

- Film Industry

- Franchising

- Trade Barriers

- Import Tariffs

- Import Requirements and Documentation

- Labeling and Marking Requirements

- U.S. Export Controls

- Temporary Entry

- Prohibited and Restricted Imports

- Customs Regulations

- Standards for Trade

- Trade Agreements

- Licensing Requirements for Professional Services

- Distribution & Sales Channels

- Selling Factors and Techniques

- Trade Financing

- Protecting Intellectual Property

- Selling to the Public Sector

- Business Travel

- Investment Climate Statement

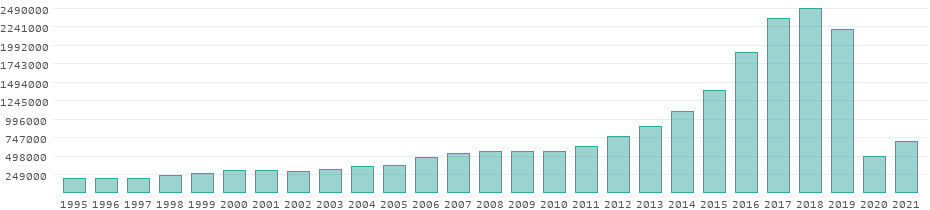

Tourism has been a growing force behind Iceland’s economy in more than a decade, with opportunities for investors in high-end tourism, including luxury resorts and hotels. The number of tourists in Iceland reached more than 2.3 million in 2018. Tourism in Iceland contracted in 2019 and 2020 due to COVID-19, and the total number of tourists went down to 2 million in 2019 and then down to 486,000 in 2020. As of 2022, the tourism sector had recovered, with 698,000 tourists in 2021, 1.8 million tourists in 2022, and a projected number of 2.3 million tourists expected for 2023. The sector has been moving away from mass tourism to high-end tourism amid increasing demand for exclusive and luxury experiences.

Units: $ millions Source: Statistics Iceland, revenue of foreign travelers, exports of goods and services.

Leading Sub-Sectors

High-end resorts and activities.

Opportunities

Hotel and resort construction outside of the capital area, near unique locations, as well as exclusive or high-end activities.

American-Icelandic Chamber of Commerce

Icelandic Federation of Trade

Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority (MAST)

Invest in Iceland

Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Innovation

Ministry of Culture and Business Affairs

Business Iceland

SA Confederation of Icelandic Enterprise

U.S. Embassy in Iceland

Vinbudin (ATVR)

Iceland Mag

Tourism's contribution to GDP doubled since 2010: 8.2% of GDP in 2016

By Staff | Sep 26 2017

Navigating Ice and snow at Seljalandsfoss Tourism has quickly become a major pillar of the Icelandic economy. Photo/Pjetur

Tourism has become a major pillar of the Icelandic economy since 2010. The current boom in tourism began in 2010, when the Eyjafjallajökull eruption focused the world's attention on Iceland. Since then the share of tourism in GDP has grown every year, from ca 3% in 2011 to 6.7% in 2015, the latest year for which Statistics Iceland has figures.

According to figures from Statistics Iceland tourism's share of GDP was 5.6% in 2014 and 4.9% in 2013. Statistics Iceland notes that not only has the share of tourism in the gross domestic product of Iceland increased each year since 2011, the rate of growth has also increased.

Statistics Iceland has not yet released figures on the share of tourism in 2016, but analysis by economists at Landsbankinn bank puts this figure at 8.2%. However, Landsbankinn also estimates that tourism made a larger contribution to GDP in 2010 than Statistics Iceland. Landsbankinn estimates that tourism contributed 4.7% to GDP in 2010.

Read more: More signs growth in tourism is starting to level off: Only 2% increase in hotel stays

Despite the growing importance of tourism it still contributes less to Icelandic GDP than other industries, most notably fishing and fish processing, which contributed 8.2% to GDP. The total number of foreign visitors grew by 36% in 2016, compared to a growth of 27% in 2015. However, there are signs that the growth in tourism has slowed down in 2017, compared to 2016.

- Full profile

Ask the experts

Do you want to know more about this subject? Please send us a line at [email protected] .

Share your experience with us

Have you had an experience related to the contents of this article? Let us know!

Editor's Picks

The winter wonders of Iceland

Tourists in great danger taking selfies by the beautiful Stuðlagil

Quick primer on Bárðarbunga, Iceland's most powerful volcano

Rainbow flags all around Reykjavík during Pence visit

Unusual land uplift in Reykjanes peninsula

WOW Air returns: Flying to Washington in October

Friends of Iceland Magazine name their favourite thing about Reykjavík

Guide: The street food of Reykjavík - Not just hot dogs anymore

Photos: Reykjavík fire department rescues cat from tree

Walking path above Skógafoss waterfall in S. Iceland closed to protect vegetation

Follow iceland mag.

Join our weekly hand curated newsletter to have all the latest news from Iceland sent to you

Don't worry, we won't spam you. Promise!

Most popular

Watch: incredible video from the stunning þrídrangar lighthouse, south iceland.

The otherworldly art of the Central Highlands: Aerial photos of Tungnaá river

No sun seen on Ísafjörður's "sun day"

President of Iceland announces that he would ban pineapple as a pizza topping

11 things to know about the present day practice of Ásatrú, the ancient religion of the Vikings

Iceland's two blue water pools: The Blue Lagoon vs. Mývatn Nature Baths

Popular videos

Watch: wonderful drone video of haymaking in north iceland.

Watch an awe-inspiring video from Iceland

Come prepared! Video reminds us travelling in the highlands is never a walk in the park!

Spectacular NASA satellite photo of the Holuhraun eruption

Video: Strokkur bursting geyser spews scalding hot water over spectators

Iceland, from boom to bust to tourist hotspot

Iceland reinvented itself as a major travel destination after the 2008 financial crisis. Will it experience a similar post-pandemic boom?

By Jenna Gottlieb

In the early 2000s, Iceland’s economy was riding high, as its three banks — Landsbanki, Kaupþing and Glitnir — had extensive international operations and attracted money from across the globe. Cash was flowing in and out at an unprecedented rate, and by the end of 2007, the country’s three banks held assets that were more than 10 times the size of Iceland’s GDP. Facilitated by favorable international credit, the banks’ gross foreign debt rose from the equivalent of 43% of GDP in 2002 to over 700% of GDP by the end of September 2008.

Everything changed in the fall of 2008. In the United States, Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy in the largest filing ever, an opening move that helped usher in the Great Recession. Iceland’s over-leveraged banks brought the country to its knees.

Everything about Iceland

- Population: 371,580 in 2021

- Total workforce: 213,413

- Capital: Reykjavík, pop. 134,000

- Land size: 102,775 sq km

- Official language: Icelandic

- Currency: Icelandic krona (ISK)

- Affiliations: NATO, Schengen Area, EEA, WTO, IMF, COE, OSCE

- GDP: $23.5 billion in 2021

- GDP per capita: $55,213

With a dramatic drop in the value of the Icelandic krona, 80% of the Iceland Stock Exchange was wiped out overnight. Every second business in Iceland went bankrupt, and the unemployment rate skyrocketed. In a matter of three days, 97% of Iceland’s banking sector had collapsed. Fear quickly turned to anger in the capital city of Reykjavík, and locals protested outside Iceland’s parliament. They were the largest protests in the country’s history. Thousands of Icelanders banged kitchenware outside parliament for weeks, which led to the events being known as the “Pots and Pans Revolution.”

In December 2008, Iceland had to be bailed out by the International Monetary Fund, and its citizens had to grapple with staggering debts, lost jobs and foreclosed homes. They were dark times for Iceland. By November 2008, the unemployment rate had tripled, and more than 6,000 people in a country of about 372,000 had lost their homes.

And then on the heels of that financial devastation, another catastrophe hit. In April 2010, the Eyjafjallajökull volcano erupted in southern Iceland, shutting down air travel in much of Europe for six days. The eruption left more than 10 million travelers stranded across more than 20 countries. Footage of the enormous ash cloud dominated the global news for days.

Although the eruption compounded an already difficult situation, these two disasters had created fertile ground for a new beginning.

The turnaround

With Iceland suddenly on people’s radars around the world, international travelers became interested in the scenic island and the weak krona, and budget airlines like WOW Air and Easyjet began serving Iceland’s international airport. Visitors seeking a holiday on a budget helped Iceland recover from the crash.

“The eruption brought awareness to the public,” says Sigríður Dögg Guðmundsdóttir, the head of Visit Iceland. “Tourism was extremely important to get us back on our feet after the crash, and it grew into our biggest export industry.”

The tourism sector has taken off, with a 328% yearly increase in foreign visitors between 2010 and 2019. In 2011, the tourism sector constituted 3.7% of Iceland’s GDP; in 2019 it was 8%. As for the labor market, tourism is vital for job creation as more tourists have led to an increase in hotels, restaurants and companies offering tours. According to Statistics Iceland, there were 30,000 tourism-related jobs in Iceland in 2018, compared to 15,700 jobs in 2010.

“Most people say nature is the biggest draw, but Iceland is also known because the number of activities and tours has grown,” Sigríður says. “Iceland tourism has become a strong industry with quality hotels and restaurants, activities and, of course, nature.”

Tourists began pouring into Iceland as airlines saw the business opportunity and it became measurably easier to visit. “We saw an increase in flights to Iceland from more airlines, and that made Iceland more accessible,” Sigríður says. “In Iceland, we had WOW Air offering budget flights to cities in the U.S. and Europe until 2019, and now we have PLAY Airlines offering budget flights.” For summer 2022, an anticipated 25 airlines will operate flights to Iceland, including local carriers Icelandair and PLAY, as well as Delta, United, British Airways and SAS.

The demographics of tourists has changed as well. “Before the crash, most tourists came from the U.K., then the U.S., China and Denmark,” Sigríður says. “In 2019, the majority of tourists came from the U.S., followed by U.K., Germany and China.”

Iceland’s profile also rose as it became a popular setting for movies and TV shows — which wasn’t a fluke. After the financial crash, the Icelandic government introduced tax incentives for movie and TV productions shot in Iceland, with TV and movie producers able to get back 25% of their production costs.

And so Iceland took center stage in films including “Prometheus” (2012), “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” (2013), “Oblivion” (2013), “Interstellar” (2014), and “Fast & Furious 8” (2017). The TV show “Game of Thrones” filmed in Iceland several times throughout the series. Diehard fans are eager to visit filming locations, and tour operators are ready to show them sites like Þingvellir National Park in the south and Lake Mývatn in the north.

“When we ask people why they came to Iceland, 35% say they saw Iceland in a film or TV show,” Sigríður says. “Social media also helps marketing as Icelandic nature is popular material for social media apps like Instagram.”

Tourism was a business driver in Iceland for nearly 10 years, and the country enjoyed a very low unemployment rate. But then the Covid-19 pandemic hit. As a small country dependent on tourists, Iceland experienced severe and immediate economic pain.

Navigating Covid-19

Leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic, tourism had been Iceland’s largest export for several years. According to data from the Iceland Chamber of Commerce, the sector’s growth peaked in 2017, when tourism accounted for 41.5% of the country’s total exports. After the Covid-19 crisis, it accounted for only 11.2% in 2020. With Iceland’s most significant economic sector hurt, overall exports contracted by 30.5% in 2020.

Iceland’s tourism economy

Nearly one-third of the country’s tourism industry jobs disappeared by the end of 2020, down from 30,000 in 2018 to 21,000 in 2020. However, the Icelandic government took steps to minimize the pain for tourism companies. In March 2021, Iceland became the first country in the Schengen area to open to all vaccinated travelers. “We are fortunate that the government has been supportive during Covid,” Sigríður says. “We opened to vaccinated tourists early, and we also offered testing at the border, and while the number of tourists was understandably low, these measures helped.”

The government also offered loans and wage schemes to tourism companies to keep as many people employed as possible and prevent bankruptcies. But Iceland’s GDP still took a hit during the pandemic. Activities related to travel bookings, air transport, accommodation and restaurants decreased by between 50% and 75% compared to 2019.

The road to recovery has been slow, but the labor market situation in Iceland has improved. The government projects that the unemployment rate will sink to 4.3% in 2022, close to pre-pandemic levels.

Iceland’s unemployment rate

“We are just 370,000 people on the island, which is about half the geographical size of the U.K.,” Sigríður says. “It is a challenge to maintain a good level of service, and tourism demand has helped us build, improve and deliver quality. This is important to Iceland’s economy.”

It should also be noted that Iceland has had some luck recently with volcanic eruptions. Just as people were fascinated by the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption, at the height of Covid-19 in March 2021, Fagradalsfjall erupted, spewing rivers of lava in a remote area of the Reykjanes peninsula. Dubbed a “tourist eruption” as it posed no danger to local residents, thousands of Icelanders flocked to the site to watch the power and beauty of nature. Tourists were also eager to visit, and the volcano produced free marketing for six months as Fagradsalsfjall put on a show until September 2021, when it went dormant.

Iceland lifted all Covid-19 entry restrictions in March 2022, welcoming both vaccinated and unvaccinated visitors, and tourism executives have high hopes for a strong summer season. “We’re not out of the woods yet as tourism companies are in debt and more workers are needed,” Sigríður says. “But summer bookings are looking good, and we are cautiously optimistic.”

Payroll in Iceland

Iceland residents are liable for tax payments in Iceland on their worldwide income. Non-resident individuals staying temporarily in Iceland are subject to national income tax on money earned by employment there. The corporate income tax rate in Iceland is 20%. Payroll is administered monthly.

Income tax rate:

- Up to ISK 4.2 million: 31.45% income tax

- ISK 4.2 million to 11.8 million: 37.95% income tax

- More than ISK 11.8 million: 46.25% income tax

Social security : Employees contribute 4% of their wages, and employers contribute 11.5%. Social security includes pensions, health insurance and disability insurance.

Holidays: The Icelandic unions negotiate paid leave. The minimum holiday time is 24 days per year.

Sources : Iceland Chamber of Commerce , Statistics Iceland , PwC Worldwide Tax Summaries

Based in Iceland, Jenna Gottlieb is a freelance journalist and Iceland guidebook author. She has written for publications including the Associated Press, CNN Travel and Quartz. Before moving to Iceland in 2012, she worked in New York on the staffs of Pensions & Investments, American Banker and Private Equity International. Jenna is the author of the Moon Iceland guidebook, published by Hachette; the 3rd edition was published May 2020.

Michelle Peters has completed over 5,000 parabolas on more than 200 flights as an educator with a commercial space company.

After the pandemic nearly halted leisure travel, the global cruise industry — and the many Filipino workers who power it — are back at sea.

The entertainment capital of the world was hit hard by the pandemic, but Las Vegans are getting back in the game.

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Quarterly.

The Outlook for Iceland’s Tourism Industry in 2022

Tourism’s Importance to Jobs and Economic Growth in Iceland

Tourism provides 39% of Iceland’s annual export revenue and contributes about 10% to the country’s GDP. Iceland’s tourism industry accounts for 15% of the workforce. In 2017, 47% of Iceland’s newest jobs were in some way related to the tourism industry.

Iceland experienced a devastating financial crisis in 2008. Job availability dropped nationwide, the poverty rate increased and the GDP dropped dramatically in the following years. It took some forecasting, but the Icelandic government developed plans calling for the tourism industry to be the savior of the Icelandic economy.

To this end, the government established a brand new Tourist Control Centre , which coordinates the government’s work in tourism nationwide. It creates new typical tourist surveys and improved cooperation under the government’s four tourism ministries. The government also implemented efforts to track the most popular tourist destinations and receive input from tourists on how to improve their experiences at those destinations.

Iceland’s tourism is so popular that the government has had to devise limits on how long individuals can rent on Airbnb and on whom must receive limitations. Rental cars are similarly limited, with nearly 80% of tourists reported renting a car at least once during their visit to Iceland. The airfare to Iceland is one of the cheapest deals year-round.

The tourism industry has been primarily responsible for the economic boom that has occurred since 2012. The plans that the Icelandic government developed went into effect in Fiscal Year 2012 and involved the government’s expanding funding opportunities in the tourism industry.

Since the expansion of the tourism industry, the increase in job availability and economic growth, Iceland has made great strides in keeping the poverty rate low and the population of those at-risk of poverty lower than what was possible pre-2012.

Impact of COVID-19 on Iceland’s Tourism Industry

Iceland has the lowest poverty rate in the world, but the COVID-19 pandemic put this at risk. The international average for a country’s poverty rate is 11%, but Iceland has the world beat. The country’s poverty rate is at 4.9% and has been dropping since the expansion of the tourism industry.

Furthermore, there were an estimated 36 Icelandic citizens for every 1,000 who were at risk of falling into poverty in 2008, at the beginning of the economic crisis. Since then, the number rose briefly above 40 individuals then rose and fell for several years, but distinctly dropped in 2014. This coincided with the beginning of the full establishment and implementation of Iceland’s expanded tourism industry.

The pandemic’s impact on tourism left the country with another drop in jobs and an economic dip. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Iceland experienced a 10-month long halt in tourism. Iceland’s GDP dropped from $24 billion to $19 billion in one year largely because of the loss of tourism between 2019 and 2020, according to Data Commons.

Expected Resurgence in Iceland’s Tourism

As soon as it became feasibly safe, Iceland reopened its borders to tourists with clear instructions . First, it allowed tourists to travel to the country as long as they isolated themselves for 14 days prior to their trip and were able to provide a negative COVID-19 test taken within 72 hours of arrival in Iceland. Since then, Iceland has allowed its visitors to arrive without those other restrictions as long as the tourists are fully vaccinated and boosted against the virus.

The increase in Iceland’s tourism is not unprecedented. In 2018, the increase in tourism was 5.4% and in 2017, it was 24.1%. Icelandair, the main airline for travel to Iceland, has its own plan for balancing safety and getting as many tourists to Iceland as feasible in the works.

Iceland’s central bank, Islandsbaski is expecting a minimum of 1 million tourists to Iceland, but as many as 1.3 million may come. In November 2021, there were a meager 75,000 tourists for the entire month. However, this is more than 20 times the final tally for tourists for that month in the preceding year.

Even though tourism paused for the better part of a year, the tourism industry is ready and raring to go. Despite the pains of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Icelandic tourism industry will reopen in 2022 as much as possible and the economic boost to come from it is invaluable.

– Clara Mulvihill Photo: Flickr

“The Borgen Project is an incredible nonprofit organization that is addressing poverty and hunger and working towards ending them.”

-The Huffington Post

Inside the borgen project.

- Board of Directors

Get Smarter

- Global Poverty 101

- Global Poverty… The Good News

- Global Poverty & U.S. Jobs

- Global Poverty and National Security

- Innovative Solutions to Poverty

- Global Poverty & Aid FAQ’s

Ways to Help

- Call Congress

- Email Congress

- 30 Ways to Help

- Volunteer Ops

- Internships

- The Podcast

- Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

Travel and tourism's contribution to GDP in Iceland in 2017, by type

Contribution of travel and tourism to gdp in iceland in 2017, by type (in billion isk).

Additional Information

Show sources information Show publisher information Use Ask Statista Research Service

Europe, Iceland

* Based on real 2017 prices. The following indicators were used to calculate the total value of contribution: Direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP (Internal tourism consumption & Purchases by tourism providers, including imported goods), Domestic supply chain, Capital investment, Government collective spending, Imported goods from indirect spending, Induced values. The source provides the following definition: "GDP generated by industries that deal directly with tourists, including hotels, travel agents, airlines and other passenger transport services, as well as the activities of restaurant and leisure industries that deal directly with tourists. It is equivalent to total internal Travel & Tourism spending within a country less the purchases made by those industries (including imports)."

Other statistics on the topic

Accommodation

International visitor arrivals in Finland 2022, by country of origin

Leisure Travel

Visitor arrivals in Helsinki 2022, by country of origin

Number of outbound trips from Finland 2022, by country of destination

Number of arrivals in tourist accommodation in Finland 2012-2022

- Immediate access to statistics, forecasts & reports

- Usage and publication rights

- Download in various formats

You only have access to basic statistics.

- Instant access to 1m statistics

- Download in XLS, PDF & PNG format

- Detailed references

Business Solutions including all features.

Other statistics that may interest you

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in the Netherlands 2019-2022

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Russia 2012-2019

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Germany 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Portugal 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Netherlands 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Turkey 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Croatia 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Greece 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in the UK 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Europe 2012-2028

- Leading European countries in the Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Europe 2019-2022

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Europe 2019-2022

- Share of travel and tourism expenditure in the Netherlands 2019-2022, by type

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Finland 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Finland 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to employment in Europe 2012-2028

- Distribution of travel and tourism expenditure in Europe 2019-2022, by type

- International tourism spending in Europe 2019-2022

- Domestic tourism spending in Europe 2019-2022

- Countries with the highest outbound tourism expenditure worldwide 2019-2022

- Leading countries in the MEA in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2018

- Countries with the highest number of inbound tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022

- International tourism receipts of India 2011-2022

- Revenue share from tourism in India 2013-2022, by segment

- Annual revenue of China Tourism Group Duty Free 2013-2023

- Foreign exchange earnings from tourism in India 2000-2022

- Number of international tourist arrivals in India 2010-2021

- Change in number of visitors from Mexico to the U.S. 2018-2024

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in France 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Turkey 2019-2023

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Russia 2019-2023

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Estonia 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism direct contribution to GDP in Hungary 2017, by tourist type

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Croatia 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Poland 2012-2028

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Czechia 2012-2028

- Changed opening hours in the tourism sector due to the coronavirus in Norway 2020

- Travel and tourism's direct contribution to employment in Portugal 2012-2028

- Tourism contribution to Spanish GDP 2006-2023

- Cruise tourists' spending in Costa Rica 2010-2022

- Tourists from the Americas in Spain 2016-2022, by origin

- Overnight stays by inbound tourists in Norway 2021, by county

- Tourism employment in Sweden 2015-2020

- Liquidity problems in the tourism industry due to COVID-19 in Norway 2021, by sector

- Share of layoffs in the tourism industry due to COVID-19 in Norway 2021, by sector

- Tourism employment in Norway 2011-2020

- Employee number in travel agency and tour operator services in Norway 2011-2019

- Annual value added of the tourism industry in Norway 2011-2019

Other statistics that may interest you Statistics on

About the industry

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in the Netherlands 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Russia 2012-2019

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Germany 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Portugal 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Netherlands 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Turkey 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Croatia 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Greece 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in the UK 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to GDP in Europe 2012-2028

About the region

- Premium Statistic Leading European countries in the Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Europe 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Europe 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Share of travel and tourism expenditure in the Netherlands 2019-2022, by type

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Finland 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Finland 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's direct contribution to employment in Europe 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic Distribution of travel and tourism expenditure in Europe 2019-2022, by type

- Basic Statistic International tourism spending in Europe 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Domestic tourism spending in Europe 2019-2022

Selected statistics

- Premium Statistic Countries with the highest outbound tourism expenditure worldwide 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Leading countries in the MEA in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2018

- Premium Statistic Countries with the highest number of inbound tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic International tourism receipts of India 2011-2022

- Basic Statistic Revenue share from tourism in India 2013-2022, by segment

- Premium Statistic Annual revenue of China Tourism Group Duty Free 2013-2023

- Basic Statistic Foreign exchange earnings from tourism in India 2000-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of international tourist arrivals in India 2010-2021