- APPLIED PHYSICS

- ENVIRONMENT

- ATMOSPHERIC

- PALEONTOLOGY

- OCEANOGRAPHY

- GENETICS & MOLECULAR BIOLOGY

- MICROBIOLOGY

- ECOLOGY & ZOOLOGY

- NEUROSCIENCE

- CANCER RESEARCH

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- PHARMACOLOGY

- CLINICAL RESEARCH

- ANTHROPOLOGY

- ARCHAEOLOGY

- SCIENCE EDUCATION & POLICY

- SCIENCE HISTORY

- PHILOSOPHY & ETHICS

- MATHEMATICS

- SCIENCE & SOCIETY

- SPORTS SCIENCE

- RANDOM THOUGHTS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging

- Science Podcast Or Perish?

- Type 2 Diabetes Medication Tirzepatide May Help Obese Type 1 Diabetics Also

News Releases From All Over The World, Right To You...

Related articles

- Columbus Got There First: Chicken Bones Tell True Story Of Pacific Migration

- Chicken DNA Suggests Polynesians Introduced Them To South America

- Did Chickens Reach America Before Columbus?

- 4600 BC: Hunters, Gatherers, Pig Owners

- Sugar – The Food Nobody Needs, But Everyone Craves

Know Science And Want To Write?

Donate or buy swag.

- Popular Now

- New Comments

- Despite Little Demand, 2024 Electric Car Sales Will Be Up To 17 Million, Says Advocacy Group

- Oil Kept Congo From Starving - Western Academics Don't Seem To Like That

- Voyager Has Come Back Online After 5 Months

- California Is Lying About Recycling Plastic: Happy Earth Day

- Look At This Amazing Chart Of What Science Did For The Poor In the Last 100 Years

- National Medal of Science Nominations Now Open

- North America Is About To Get Its Longest Partial Eclipse In The Last 580 years

- Farmers Can Get Infrastructure Funds From The Government Now Also - But You Have To Apply By Nov. 22

- US Ag Secretary Perdue To Debate EU Ag Commissioner Wojciechowski On Food Regulations Wednesday - Tune In Here

- Natural History Museum of Utah: Research Quest Live Is Hosting Free Daily Classes For Kids

Similar content being viewed by others

Multiple hominin dispersals into Southwest Asia over the past 400,000 years

Huw S. Groucutt, Tom S. White, … Michael D. Petraglia

Global processes of anthropogenesis characterise the early Anthropocene in the Japanese Islands

Mark Hudson, Junzō Uchiyama, … Kara C. Hoover

Evidence from personal ornaments suggest nine distinct cultural groups between 34,000 and 24,000 years ago in Europe

Jack Baker, Solange Rigaud, … Francesco d’Errico

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information .

Code availability

All Bayesian code generated during this study is included in the Supplementary Information .

Bellwood, P. First Farmers (Blackwell, 2005).

Kirch, P. V. The Lapita Peoples: Ancestors of the Oceanic World (Blackwell, 1997).

Spriggs, M. The Island Melanesians (Blackwell, 1997).

Kirch, P. V. On the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact (Univ. California Press, 2017).

Kirch, P. V. Talepakemalai: Lapita and its Transformations in the Mussau Islands of Near Oceania (Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 2021).

Reith, T. M. & Athens, J. S. Late Holocene human expansion into Near and Remote Oceania: a Bayesian model of the chronologies of the Mariana Islands and Bismarck Archipelago. J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 14 , 5–16 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Bedford, S. et al. in Debating Lapita: Distribution, Chronology, Society and Subsistence (eds Bedford, S. & Spriggs, M.) 5–33 (ANU Press, 2019).

Skoglund, P. et al. Genomic insights into the peopling of the Pacific. Nature 538 , 510–513 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Summerhayes, G., Field, J., Shaw, B. & Gaffney, D. The archaeology of forest exploitation and change in the tropics during the Pleistocene: the case of Northern Sahul (Pleistocene New Guinea). Quat. Int. 448 , 14–30 (2017).

Lilley, I. in A Companion to Social Archaeology (eds Meskell, L. & Preucel, R. W.) 287–312 (Blackwell, 2004).

van Oven, M. et al. Human genetics of the Kula Ring: Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA variation in the Massim of Papua New Guinea. Eur. J. Hum. Genet . 22 , 1393–1403 (2014).

Allen, G. R., Kinch, J. P., McKenna, S. A. & Seeto, P. (eds) A Rapid Marine Biodiversity Assessment of Milne Bay Province, Papua NewGuinea—Survey II (2000) (Conservation International, 2003).

Webb, L. E., Baldwin, S. L. & Fitzgerald, P. G. The Early–Middle Miocene subduction complex of the Louisiade Archipelago, southern margin of the Woodlark Rift. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 15 , 4024–4046 (2014).

Summerhayes, G. R. in From South ea st Asia to the Pacific: Archaeological Perspectives on the Austronesian Expansion and the Lapita Cultural Complex (eds Chui, S. & Sand, C.) 129–172 (Academic Sinica, 2007).

Summerhayes, G. et al. in Debating Lapita: Distribution, Chronology, Society and Subsistence (eds Bedford, S. & Spriggs, M.) 379–402 (ANU Press, 2019).

O’Connor, S. et al. The power of paradigms: examining the evidential basis for Early to Mid-Holocene pigs and pottery in Melanesia. J. Pac. Archaeol. 2 , 1–25 (2011).

Google Scholar

Matisoo-Smith, E. & Robins, J. Origins and dispersals of Pacific peoples: evidence from mtDNA phylogenies of the Pacific rat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101 , 9167–9172 (2004).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Spriggs, M. in Report on the Lapita Homeland Project (eds Allen, J. & Gosden, C.) 222–243 (Department of Prehistory, Research School of Pacific Prehistory, Australian National University, 1991).

Field, J., Shaw, B. & Summerhayes, G. Pathways to the interior: human settlement in the Simbai-Kaironk Valleys of the Madang Province, PNG. Aust. Archaeol. 88 , 2–17 (2022).

Gaffney, D. et al. Earliest pottery on the New Guinea mainland reveals Austronesian influences in Highland environments 3000 years ago. PLoS ONE 10 , e0134497 (2015).

Leclerc, M., Tache, K., Bedford, S. & Spriggs, M. in Archaeologies of Island Melanesia: Current Approaches to Landscapes, Exchange and Practice (eds Leclerc, M. & Flexner, J. L.) 179–190 (ANU Press, 2019).

Gorecki, P. in Poterie Lapita et Peuplement (ed. Galipaud, J. C.) 27–47 (ORSTOM, 1992).

Hawkins, S. Human Behavioural Ecology, Anthropogenic Impact and Subsistence Change at the Teouma Lapita Site, Central Vanuatu, 3000–2500 BP . PhD thesis, Australian National Univ. (2015).

Butler, V. L. Fish feeding behaviour and fish capture: the case for variation in Lapita fishing strategies. Archaeol. Ocean. 29 , 81–90 (1994).

Shaw, B. et al. 2500-year cultural sequence in the Louisiade Archipelago (Massim region) of eastern Papua New Guinea reflects adaptive strategies to remote islands since Lapita settlement. Holocene https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683620908641 (2020).

Szabo, K. & Amesbury, J. R. Molluscs in a world of islands: the use of shellfish as a food resource in the tropical island Asia-Pacific region. Quat. Int. 239 , 8–18 (2011).

Kinch, J. P. Changing Lives and Livelihoods: Culture, Capitalism and Contestation over Marine Resources in Island Melanesia . PhD thesis, Australian National Univ. (2020).

Frazier, J. in From Hooves to Horns, from Mollusc to Mammoth , Manufacture and Use of Bone Artefacts from Prehistoric Times to the Present (eds Luik, H. et al.) 359–382 (Muinasaja Teadus, 2005).

Torrence, R. et al. Tattooing tools and the Lapita Cultural Complex. Archaeol. Ocean. 53 , 58–73 (2018).

Sheppard, P. in Lapita: Oceanic Ancestors (eds Sand, C. & Bedford, S.) 240–251 (Musee du Quai Branly, 2010).

Mialanes, J. et al. Imported obsidian at Caution Bay, south coast of Papua New Guinea: cessation of long distance procurement c.1900 cal BP. Aust. Archaeol. 82 , 248–262 (2016).

Skelly, R., Ford, A., Summerhayes, G., Mialanes, J. & David, B. Chemical signatures & social interactions: implications of west Fergusson Island obsidian at Hopo, east of the Vailala River (Gulf of Papua), Papua New Guinea. J. Pac. Archaeol. 7 , 126–138 (2016).

Ross-Sheppard, C., Sand, C., Balenaivalu, J. & Burley, D. Kutau/Bao obsidian—extending its eastern distribution into the Fijian northeast. J. Pac. Archaeol. 4 , 79–83 (2013).

Irwin, G. & Holdaway, S. in Oceanic Culture History: Essays in Honour of Roger Green (eds Davidson, J. M. et al.) 225–235 (New Zealand Journal of Archaeology Special Publication, 1996).

Irwin, G., Shaw, B. & McAlister, A. The origins of the Kula Ring: archaeological and maritime perspectives from the southern Massim and Mailu areas of Papua New Guinea. Archaeol. Ocean. 54 , 1–16 (2019).

Reepmeyer, C. The Obsidian Sources and Distribution Systems Emanating from Gaua and Vanua Lava in the Banks Islands of Vanuatu. PhD thesis, Australian National Univ. (2009).

Green, R. C. Fergusson Island obsidian from the D’Entrecasteaux Group in a Lapita site of the Reef Santa Cruz Group. NZ J. Archaeol. 11 , 87–99 (1989).

Davies, H. L. Geological Observations in the Louisiade Archipelago Vol. 1959/133 (Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics, 1959).

Smith, I. E. & Pieters, P. E. The geology of the Deboyne Island Group, southeastern Papua. BMR 139 , 71–74 (1973).

Bickler, S. H. & Turner, M. Food to stone: investigations at the Suloga adze manufacturing sites, Woodlark Island, Papua New Guinea. J. Polyn. Soc. 111 , 11–43 (2002).

Ross, M. D. Proto Oceanic and the Austronesian Languages of Western Melanesia (Pacific Linguistics, 1988).

Dickinson, W. R. Beach ridges as favored locales for human settlement on Pacific Islands. Geoarchaeology 29 , 249–267 (2014).

Woodroffe, S. A. Testing models of mid to late Holocene sea-level change, North Queensland, Australia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28 , 2474–2488 (2009).

Kaplin, P. in The Ecosystems of Small Islands in the Southwest Pacific (The Sixth Expedition of the SS ‘Calisto’) UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies (eds Pernetta, J. & Manner, H.) 9–28 (UNEP, 1994).

McNiven, I. et al. New direction in human colonisation of the Pacific: Lapita settlement of South Coast New Guinea. Aust. Archaeol. 72 , 1–6 (2011).

Skelly, R., David, B., Petchey, F. & Leavesley, M. Tracking ancient beach-lines inland: 2600-year-old dentate-stamped ceramics at Hopo, Vailala River region, Papua New Guinea. Antiquity 88 , 470–487 (2014).

David, B. et al. in Debating Lapita: Distribution, Chronology, Society and Subsistence (eds Bedford, S. & Spriggs, M.) 61–88 (ANU Press, 2019).

McNiven, I. J. et al. Mask Cave: red-slipped pottery and the Australian-Papuan settlement of Zenadh Kes (Torres Strait). Archaeol. Ocean. 41 , 49–81 (2006).

Tochilin, C. et al. Using U-Pb ages of detrital zircons to source temper sands in ancient ceramics: a case study from the Southwest Pacific. J. Archaeol. Sci. 39 , 2583–2591 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar

McNiven, I. J. in Conne ctions Across the Coral Sea: A Story of Movement (eds Mitchell, B. & Ridgway, R.) 8–15 (Queensland Museum, 2021).

Lilley, I. in Debating Lapita: Distribution, Chronology, Society and Subsistence (eds Bedford, S. & Spriggs, M.) 105–114 (ANU Press, 2019).

Dickinson, W. R. Temper Sands in Prehistoric Oceanic Pottery: Geotectonics, Sedimentology, Petrography, Provenance Special Paper 406 (Geological Society of America, 2006).

Shaw, B. The Archaeology of Rossel Island, Massim, Papua New Guinea: Towards a Prehistory of the Louisiade Archipelago Vol. 2, 125–135. PhD thesis, Australian National Univ. (2015).

Shaw, B. The Archaeology of Rossel Island, Massim, Papua New Guinea: Towards a Prehistory of the Louisiade Archipelago Vol. 2, 136–138. PhD thesis, Australian National Univ. (2015).

David, B. et al. Lapita sites in the Central Province of mainland Papua New Guinea. World Archaeol. 43 , 576–593 (2011).

Chiu, S. in Debating Lapita: Distribution, Chronology, Society and Subsistence (eds Bedford, S. & Spriggs, M.) 307–334 (ANU Press, 2019).

Walter, R. & Sheppard, P. Archaeology of the Solomon Islands (Univ. Hawaii Press, 2017).

Lipson, M. et al. Three phases of ancient migration shaped the ancestry of human populations in Vanuatu. Curr. Biol. 30 , 4846–4856 (2020).

Shaw, B. et al. Smallest late Pleistocene inhabited island in Australasia reveals the impact of post-glacial sea-level rise on human behaviour from 17,000 years ago. Quat. Sci. Rev. 245 , 106522 (2020).

Shaw, B. et al. Emergence of a Neolithic in Highland New Guinea by 5000–4000 years ago. Sci. Adv. 6 , eaay4573 (2020).

Turney, C. et al. Radiocarbon protocols and first intercomparison results from the Chronos 14Carbon-Cycle Facility, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Radiocarbon 63 , 1003–1023 (2021).

Fink, D. et al. The ANTARES AMS facility at ANSTO. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 223–224 , 109–115 (2004).

Hua, Q. et al. Progress in radiocarbon target preparation at the ANTARES AMS centre. Radiocarbon 43 , 275–282 (2001).

Reimer, P. et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62 , 725–757 (2020).

Bronk Ramsey, C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51 , 337–360 (2009).

Ward, G. K. & Wilson, S. R. Procedures for comparing and combining age determinations: a critique. Archaeometry 20 , 19–31 (1978).

Reimer, R. & Reimer, P. An online application for Δ R calculation. Radiocarbon 59 , 1623–1627 (2017).

Heaton, T. et al. Marine20—the marine radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55,000 cal BP). Radiocarbon 62 , 779–820 (2020).

Petchey, F. et al. High-resolution radiocarbon dating of marine materials in archaeological contexts: radiocarbon marine reservoir variability between Anadara, Gafrarium, Batissa, Polymesoda spp. and Echinoidea at Caution Bay, Southern Coastal Papua New Guinea. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 5 , 69–80 (2013).

Ambrose, W. R. et al. Engraved prehistoric Conus shell valuables from southeastern Papua New Guinea: their antiquity, motifs and distribution. Archaeol. Ocean. 47 , 113–132 (2012).

Bronk Ramsey, C. Dealing with outliers and offsets in radiocarbon dating. Radiocarbon 51 , 1023–1045 (2009).

Torrence, R., Kelloway, S. & White, P. Stemmed tools, social interaction, and voyaging in early-mid Holocene Papua New Guinea. J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 8 , 278–310 (2013).

Lyman, R. L. Quantitative Paleozoology (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Edwards, H. G. M., Carter, E. A., Kelloway, S., Privat, K. L. & Harrison, T. M. Raman spectroscopic and elemental analysis of bone from a prehistoric ancestor: Mrs Ples from the Sterkfontein cave J. Raman Spectrosc. 52 , 2272–2281 (2021).

Fagri, K. & Iversen, J. Textbook of Pollen Analysis (John Wiley & Sons, 1989).

Stockmarr, J. Tablets with spores used in absolute pollen analysis. Pollen Spores 13 , 615–621 (1971).

Caffrey, M. A. & Horn, S. P. The use of lithium heteropolytungstate in the heavy liquid separation of samples which are sparse in pollen. Palynology 37 , 143–150 (2013).

Buckley, M., Collins, M., Thomas-Oates, J. & Wilson, J. C. Species identification by analysis of bone collagen using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23 , 3843–3854 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

van der Sluis, L. G. et al. Combining histology, stable isotope analysis and ZooMS collagen fingerprinting to investigate the taphonomic history and dietary behaviour of extinct giant tortoises from the Mare aux Songes deposit on Mauritius. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 416 , 80–91 (2014).

Welker, F., Soressi, M., Rendu, W., Hublin, J.-J. & Collins, M. Using ZooMS to identify fragmentary bone from the Late Middle/Early Upper Palaeolithic sequence of Les Cottés, France. J. Archaeol. Sci. 54 , 279–286 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Brooker and Panaeati Islands communities for permission and support to undertake the archaeological research. We also thank the National Museum and Art Gallery of Papua New Guinea, the National Research Institute and the Provincial Government of Milne Bay for supporting the research programme. We would like to acknowledge S. Kelloway and I. Wainwright of the XRF Facility within the Mark Wainwright Analytical Centre at the University of New South Wales for pXRF support. SEM–EDS was conducted at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Sydney node of the Microscopy Australia network. ZooMS analysis was carried out at the Department of Archaeology, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. We thank the people of Nissan Island, Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, for their hospitality and continued interest in the archaeology of their ancestors. The project was funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Award (DECRA, DE170100291) to B.S. Radiocarbon dating was partly funded by an Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation grant no. AP11908 awarded to B.S. We acknowledge financial support from the Australian Government for the Centre for Accelerator Science at ANSTO through the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Evolution of Cultural Diversity Initiative, School of Culture, History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Ben Shaw, Simon Coxe & Simon Haberle

School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Ben Shaw, Lorena Becerra-Valdivia, Chris S. M. Turney, Karen Privat & Emily Hull

Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, School of Culture, History and Language, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Ben Shaw, Simon Haberle & Felicitas Hopf

Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, School of Culture, History and Language, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

School of Culture, History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Ben Shaw, Stuart Hawkins, Mathieu Leclerc, Simon Haberle & Felicitas Hopf

Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Lorena Becerra-Valdivia & Chris S. M. Turney

Chronos 14Carbon Cycle Facility, Mark Wainwright Analytical Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Lorena Becerra-Valdivia, Chris S. M. Turney & Christopher E. Marjo

Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, School of Archaeology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Lorena Becerra-Valdivia

Division of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research), University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Chris S. M. Turney

Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Vincent Kewibu

National Museum and Art Gallery of Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Jemina Haro & Kenneth Miamba

School of Archaeology and Anthropology, College of Arts and Social Sciences, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Mathieu Leclerc & Matthew Spriggs

Vanuatu Cultural Centre, Port Vila, Vanuatu

Matthew Spriggs

Electron Microscope Unit, Mark Wainwright Analytical Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Karen Privat

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Alana Pengilley

Department of Anthropology, College of Liberal Arts, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA

Institute for Scientific Archaeology, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Tubingen, Germany

Samantha Brown

Centre for Accelerator Science, Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, Lucas Heights, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Geraldine Jacobsen

Panaeati Island, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Lincoln Wesley, Archy Losane Yapeth, Joe Norman, Steven Lincoln, Isaiah Stanley, Eyasi Sanibalath, Tau Jack, Benard Isei, David Vilan, Robert Lincoln, Lincoln Inosi, Sima Lahaga, Wesley Lincoln, Tom Eliuda, Ernest Mark, Able Moimoi, Lemeki Isaia, Felix Jack, Heke Jack, George Sadiba, Solomon Ruben, Weda Gaunedi & John Sakiusa

Brooker Island, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Robinson Nuabui, Starford Jubilee, Paul, Munt, Leon, Joseph Betuel, Kingsley, Ishmael, Edwin, Harry, G. Oscar, Joel, Jeremiah, Jimmy, Jerry, Roger, Joseph Nua, Lemeki, Nason, Thomas & Yadila

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Lincoln Wesley

- , Robinson Nuabui

- , Starford Jubilee

- , Archy Losane Yapeth

- , Joe Norman

- , Steven Lincoln

- , Isaiah Stanley

- , Eyasi Sanibalath

- , Benard Isei

- , David Vilan

- , Robert Lincoln

- , Lincoln Inosi

- , Lincoln Wesley

- , Sima Lahaga

- , Wesley Lincoln

- , Tom Eliuda

- , Ernest Mark

- , Able Moimoi

- , Lemeki Isaia

- , Felix Jack

- , Heke Jack

- , George Sadiba

- , Solomon Ruben

- , Weda Gaunedi

- , John Sakiusa

- , Joseph Betuel

- , Kingsley

- , Jeremiah

- , Joseph Nua

- & Yadila

Contributions

B.S. was responsible for conceptualization. B.S., S.C., V.K., J.H., M.L., K.M. and Brooker and Panaeati communities undertook the excavations. S. Hawkins conducted the faunal bone analysis. C.S.M.T., L.B.-V., C.E.M. (Chronos) and G.J. (ANSTO) completed the radiocarbon dating. L.B.-V. undertook Bayesian age modelling. E.H., A.P. and B.S. conducted obsidian pXRF and physical analyses. B.S. conducted sediment, pottery, lithic and shellfish analyses. K.P. conducted SEM–EDS analysis. S. Haberle and F.H. conducted sediment pollen analysis. S.B. undertook ZooMS. M.S. completed the comparative Lebang Halika record. B.S. prepared the manuscript draft and all authors were involved in editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ben Shaw .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Elizabeth Matisoo-Smith, Dylan Gaffney, Tarisi Vunidilo and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended data fig. 1 pollen from excavated sediment 25 cm below the surface (layer 1b) indicating the presence of heavily disturbed open forest canopy with shrub and herb groundcover within the last 490–310 cal bp..

1) Amaranthaceae (flowering herb/shrub), 2) Pandanus sp. (tree/shrub), 3) Poaceae (flowering grass), 4) Myrtaceae (tree/shrub), 5–6) Macraranga sp. (tree, disturbance indicator 1 ), 7) cf. Stemonurus (tree/shrub), 8) Monolete fern spore, 9) Aerial view of Gutunka Bay showing the heavily disturbed modern vegetation with cleared hillside for garden plots, dense grove of coconut and banana trees, with mangroves lining parts of the shoreline. Note that no mangrove, banana or coconut pollen was identified in the sediment. Photo 1–8 credit: Felicitas Hopf, Photo 9 credit: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Gutunka Bay excavations 2018–2019.

( a ) The layout of Squares A-B near Spade pit three during the 2018 season. ( b ) The layout of Squares C-D adjoining A-B showing the high water table during the 2019 season. ( c ) Bailing of water while removing Square A overburden and spade removal of Square D (sump) sediment. d ) The final depth profiles of Squares A–D. Squares A and D revealed a cultural deposit (Layers 6–7) before sustained Lapita settlement (Layers 5b–3, green shade). e ) Large stones and pottery recorded in situ at 190-200 cm (Spit 16, base of Layer 5b), Squares A and D. Sediment with dense charcoal inclusions at the southern end of the squares was likely a fireplace. The dense stone was uncovered in a consolidated sediment matrix consistent with sub-soils from the hillside that had washed into the bay following vegetation clearance, effectively sealing the underlying cultural deposits in Layers 6–7. Red symbols indicate the position of in situ recorded pottery from the base of Layer 5b (170-200 cm, Spits 14-16). Photos and drawing credit: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Faunal remains recovered from Layer 6 (202-255 cm) and Layer 7 (255-281 cm).

a ) Pig rib, Square A, Spit 22, Layer 6, 244–255 cm. b) Dog metapodial, Square D, Layer 6, 220–250 cm. c) Modified turtle carapace, Square A, Spit 21, Layer 6, 236–244 cm. d) Modified turtle carapace, Square A, Spit 22, Layer 6, 244–255 cm. e , f) Cuscus teeth, Square A, Spit 22, Layer 6, 244–255 cm. g) Cuscus, Square A, Spit 20, Layer 6, 226-236 cm. h) Unidentified large mammal (cf. human), Square D, Layer 7, 270 cm. i) Rat acetabulum/ilium/partial ischium and vertebra, Square A, Spit 17, Layer 6, 202-210 cm. j) Dog tooth, Square A, Spit 19, Layer 6, 221-226 cm. Photo credits: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Corrected volume of finfish bone recovered from Square A, Gutunka by NISP/m3 (A-C) and g/m3 (D-F).

Most identified remains were from herbivorous fish families (Scaridae and Acanthuridae), although carnivorous fish families were more numerous. Figure credit: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Gutunka obsidian metric and pXRF sourcing results.

(a) Box and whisker plot of all obsidian pieces (n = 387) from Squares A–D by cultural context showing median, upper and lower quartiles, and maximum and minimum weights. Dashed line marks the heaviest obsidian piece found in a Lapita context on the south Papuan Coast (2.56 g) 2 . (b) length and width of all obsidian from Squares A–D compared against 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1 length:width lines. Artefact type for obsidian pieces over 30x20mm in size shown. (c) Strontium (Sr) and Niobium (Nb) ppm concentrations for pXRF analysed obsidian pieces relative to geological source samples from the New Guinea region. (d) Factor analysis of first two principal components (unrotated) of Log10 transformed pXRF data from archaeological obsidian pieces and Fergusson geological source samples. (e) Hierarchical cluster analysis dendrogram (Between-group average linkage) showing the structure of Log10 transformed pXRF data and allocation to a geochemical source. Figure credit: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Excavated obsidian from Lapita (Layers 5b–3) and Indigenous (Layer 6) contexts categorized by interpreted tool type.

Square and layer from which each artefact was recovered is shown. Note the presence of concreted sand on some pieces from Layer 6 is consistent with deposition in an intertidal context. Photo credit: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Excavated ground and flaked stone artefacts from Gutunka.

(a) Ground and rounded amphibolite rock sourced from Misima Island. Square A, Spit 12, Layer 5b. ( b) Ground clastic sandstone, possible grindstone, sourced locally. Square A, Spit 5, Layer 3-4. ( c) Ground clastic sandstone grindstone sourced locally. Square A, Spit 10, Layer 5a. ( d) Ground agglomerate, hammerstone, sourced locally. Square A, sump, 240–250 cm b.s., Layer 6. ( e) Rounded and ground tuff with possible axe-adze sharpening grooves, sourced locally. Square A, Spit 19, Layer 6. ( f) Rounded and ground tuff with flattened end, possible abrader, sourced locally. Square A, Spit 13, Layer 5b. ( g) Ground silica-rich sandstone with cut mark sourced locally. Square A, Spit 16, Layer 5b. ( h) Water rounded sandstone with ground surfaces, sourced locally. Square D, 74 cm b.s., Layer 3. ( i) Rounded and ground andesitic sandstone, sourced locally. Square A, Spit 9, Layer 5a. (j) Quartz core, Square D, 70 cm b.s., Layer 3. ( k) chert primary flake with cortex, Square A, Spit 5, Layer 3-4. ( l) Large chert flake, SP4, 120–140 cm b.s. associated with dentate stamped Lapita pottery. ( m) Chert core, Square A, Spit 3, Layer 3. ( n) Chert flake, Square A, Spit 1, Layer 2. ( o) Chert core, Square A, Spit 11, Layer 5a. ( p) Primary chert flake with cortex, Square D, 80–90 cm b.s., Layer 3-4. ( q) Ground metasedimentary axe-adze fragment, Square D, 120–140 cm b.s., Layer 5a. ( r) Ground metasedimentary axe-adze fragment, Square A, Spit 4, Layer 3. ( s) Ground metasedimentary axe-adze fragment, Square A, Spit 3, Layer 3. ( t) Ground metasedimentary axe-adze fragment, Square A, Spit 4, Layer 3. ( u) Chert flake fragment, Square B, Spit 7, Layer 4. Chert was sourced from islands other than Brooker in the Louisiade Archipelago. Arrows indicate the location of ground surfaces consistent with broken axe/adze fragments. Photo credits: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Reef-Lagoon system surrounding Brooker Island, evidence for mid-Holocene high stand, and later beach formation in the Louisiade Archipelago.

a) Aerial drone image looking east along the Calvados island chain 500 m above Brooker Island. b) Wave cut notch in the limestone cliffs on the north side of Panaeati Island consistent with the elevated sea levels during the mid-Holocene high stand. c) Excavated section at the back of Malakai beach, Nimowa Island, 90 km from Brooker, showing beach rock and initial beach formation from 2550-2320 cal BP (Beta-479380: 2720 ± 30 BP, shell). Photo credits: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) imagery and Energy dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping of Lapita and modern sherds from Brooker Island.

The top two sherds are from the base of Layer 5b in Square A (Spit 16) and represent the earliest pottery on the island. The bottom is a modern sherd made on Brooker. Elemental mapping shows all to have an aluminosilicate matrix. Elemental mapping and point analyses identify the presence of minerals characteristic of the local igneous/metamorphic geology, with no evidence of carbonate minerals, shell or coral. White bars represent 1 mm. SEM image credits: Karen Privat. Pottery photo credits: Ben Shaw.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Excavated dentate stamped pottery and vessel forms from Gutunka.

a ) Scale drawings of decorated sherds. Note that the surfaces of some sherds had eroded, making it difficult to identify the presence of surface decoration. The proportion of decorated sherds may therefore be under-represented. Lapita pottery vessel forms from Gutunka (B, F) compared with those from Caution Bay Lapita sites (C-E) on the south coast of Papua New Guinea 3 and Lapita assemblages in the Bismarck Archipelago 4 (G). ( b ) Gutunka, Square A, layer 5a, 2750-2500 cal BP. ( c ) Bogi 1, Square Y, Spit 1, 135 cm b.s., dated to 2750-2500 cal BP. ( d ) Tanamu 1, Square N, Spit 2, ~50–70 cm b.s. dated to 2800-2750 cal BP ( e ) Bogi 1, Square F, Spit 14, 140–150 cm b.s. dated to 2900-2800 cal BP. Drawing credits: Ben Shaw.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Text 1–4 and Figs. 1–16.

Reporting Summary

Peer review file, supplementary tables.

Supplementary Tables 1–17.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shaw, B., Hawkins, S., Becerra-Valdivia, L. et al. Frontier Lapita interaction with resident Papuan populations set the stage for initial peopling of the Pacific. Nat Ecol Evol 6 , 802–812 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01735-w

Download citation

Received : 07 October 2021

Accepted : 10 March 2022

Published : 21 April 2022

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01735-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Tracking the Lapita Expansion Across the Pacific

by Veronika Meduna

Detail of the intricate pottery designs on Lapita ceremonial pots. Photo: RNZ / Veronika Meduna

The whole Lapita story is an extraordinary chapter of human history. These are the first people that get beyond the main Solomons chain. Stuart Bedford, Australian National University, Vanuatu Cultural Centre

Stuart Bedford has spent many years scouring Vanuatu’s volcanic soil for evidence of the archipelago’s first inhabitants, but one of his best discoveries came when he wasn’t looking. A digger driver who was excavating soil for a prawn farm on Vanuatu’s main island Efate discovered a richly decorated shard of pottery – and recognised it as something unusual.

Bedford and his colleague Matthew Spriggs , both archaeologists at the Australian National University in Canberra, were called in and immediately identified it as Lapita .

The serendipitous discovery soon led to a major project which unearthed not just more pottery but human remains. More than a decade later, the site at Teouma is now famous among Pacific archaeologists as the oldest Lapita cemetery, reaching back three millennia to the very beginning of an epic voyage of discovery.

- Download as Ogg

- Download as MP3

- Play Ogg in browser

- Play MP3 in browser

Archaeological excavations at Teouma. Photo: Stuart Bedford / Vanuatu Cultural Centre

The Lapita are ancestors of modern Polynesians, who later went on to explore all corners of the Polynesian triangle, from Hawaii to Easter Island and ultimately New Zealand. But 3000 years ago it was Lapita seafarers who heralded the last major prehistoric wave of migration by sailing to Vanuatu and from there out into an area known as Remote Oceania.

In July, Vanuatu’s capital Port Vila hosted the 8 th Lapita conference , which brought together scientists from disciplines as far apart as archaeology, linguistics and genetics to discuss the latest findings about the Lapita, from the techniques they used to produce their unique, elaborately decorated pottery, to their burial practices, their health, their impact on the archipelago’s ecology - and of course their Pacific sailing itinerary.

The Prime Minister of Vanuatu, Sato Kilman, left, with Stuart Bedford and Matthew Spriggs, right, at a kava ceremony to mark the opening of the Lapita conference and an exhibition at the Vanuatu Cultural Centre and national museum, in Port Vila. Photo: RNZ / Veronika Meduna

"Teouma is the first kind of really core Lapita site … so it’s given us unique insights into who the Lapita people were," says Matthew Spriggs.

From the bones and teeth, the team gleaned information about their diet and health, but most importantly perhaps, the Teouma bones confirm the Polynesian link.

We can compare the skull shape of the Lapita people and see who they resemble most among living populations today and they fit very neatly within the Polynesian/Asian mode rather than the Australian, Aboriginal and Melanesian mode. Matthew Spriggs, Australian National University, Vanuatu Cultural Centre

Spriggs says that it was during the relatively short period of Lapita expansion that change happened and, while the people at Teouma are ancestors of Polynesians, later Lapita site are more closely linked with modern Melanesians.

“It’s only during Lapita that we have evidence of extensive interactions between all the archipelagos, so from New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, through to the Solomons, Vanuatu, New Caledonia and out to Fiji. There’s extensive exchange networks, contact between these areas.”

French archaeologist Frederique Valentin is measuring up one of the 3000-year-old skulls from the Teouma cemetery, at the museum collection in Port Vila. Photo: RNZ / Veronika Meduna

At the Teouma cemetery, archaeologists also discovered 68 burial sites, and the bleached bones almost certainly belong to the first people to make landfall in Vanuatu. They unearthed clear evidence that the Lapita used their highly decorated pottery for ceremonies and rituals, but for Frederique Valentin , an archaeologist at the National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris, the bones tell a fascinating story of ritual burial practices – with headless skeletons and deliberately rearranged bones.

Hallie Buckley , a biological anthropologist at the University of Otago, has coordinated the excavation of the bones and has studied them for signs of disease.

These same bones also tell a story of hard work, and of people suffering from gout and what we now know as metabolic disease. But Anna Gosling , also at the University of Otago, says the gout may be an evolutionary consequence of protection against malaria.

Gout is a result, usually, of high serum urate levels. Pacific Island people, throughout the Pacific, have been found to have quite high levels of this particular chemical in their blood compared to most other populations worldwide, which is suggesting that there is some sort of genetic link. Anna Gosling, University of Otago

Urate has several important function: it helps maintain blood pressure, it is an anti-oxidant, and it plays a role in the body's innate immune response. During a Malaria infection, urate levels increase to stimulates an immune response.

"The argument we're trying to make here is that if you already have slightly higher urate levels in your blood, you need less red blood cells to ... burst apart before your immune system kicks in and tries to resolve the infection, which would give you quite an advantage."

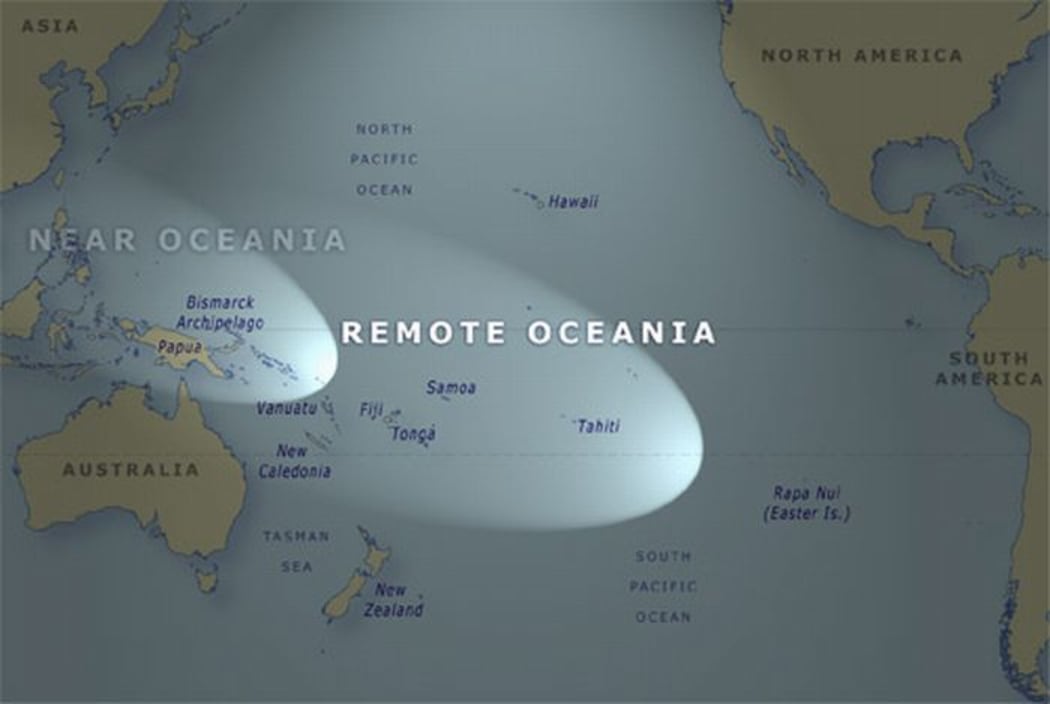

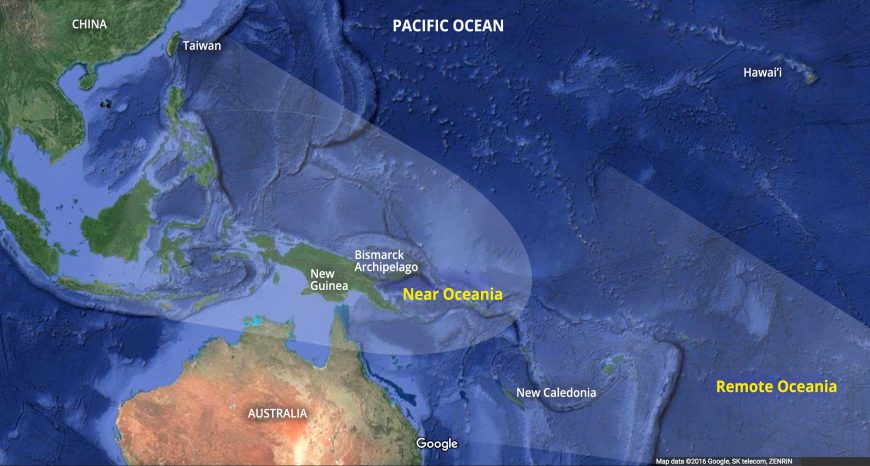

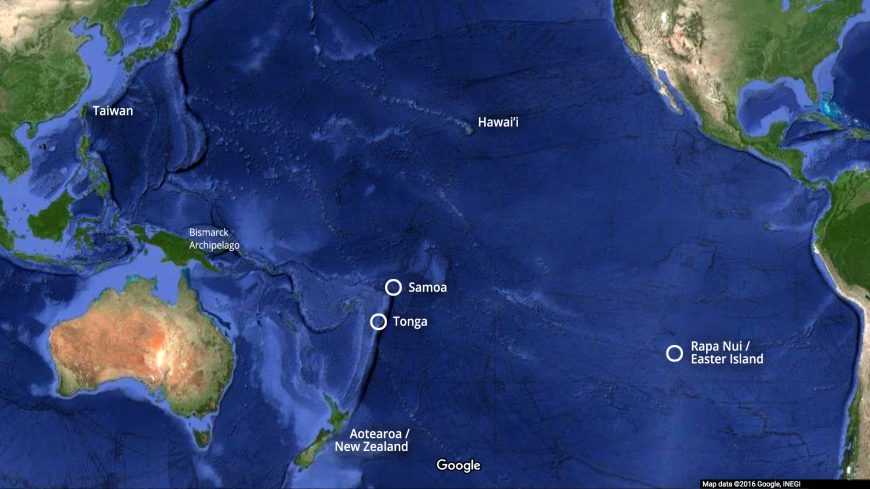

This map shows the areas known as Near and Remote Oceania. Photo: Supplied

The human settlement of the Pacific and the origins of the Polynesian people have been topics of intense debate for decades, and scientists have sought to chart the path of the Lapita expansion. Collectively they have accumulated evidence that points to an origin in island Southeast Asia, but with more clarity in some of the detail comes increasing complexity of the total picture.

The first wave of colonisation in the Pacific region began when people fanned out across an area known as Near Oceania, sometime around 40,000 years ago. Sea levels were lower then – New Guinea, Australia and the island of Tasmania were still one landmass – and these first explorers had to navigate smaller gaps of ocean. They spread as far as the Bismarck Archipelago north of Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands in the Pacific.

Patrick Kirch , an anthropologist at the University of California at Berkeley and an expert in Pacific prehistory, says for 30,000 years, the sea gap between the main chain of the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu was an invisible boundary. But then, around 3000 years ago, the Lapita, breached this voyaging barrier. Their unmistakable comb-toothed pottery is the most distinctive cultural signature they left behind, and it now helps to reconstruct their journey.

You can use the pottery and other material culture to trace the movement very clearly and with the assistance of radio carbon dating we’ve put a timeframe on that. Patrick Kirch, University of California at Berkeley

This Lapita “bursting out into this part of the Pacific that had never been occupied by humans” ended at about 800BC in Tonga and Samoa, but just what motivated the rapid expansion is still a point of debate.

Population pressure is often discussed as one option, but Kirch thinks people were pulled rather than pushed. “By pull I mean things like new resources. We know in Vanuatu they had these tortoises and pigeons, they were great food items.”

Also, he says, there could be social factors such as a hierarchical clan structure in which younger sons may have wanted to establish elsewhere.

More than 350 Lapita pots have been unearthed at the Teouma cemetery, but only few were complete, still showing the elaborate stamped motifs. Photo: RNZ / Veronika Meduna

Although the dentate pottery – edged with toothlike projections – is the most consistent Lapita identifier, it’s clear that the people carried with them a suite of other skills, including open-ocean navigation, boat-building, fishing and agriculture. Archaeologists prefer to use the term Lapita Cultural Complex, rather than implying that Lapita was a homogenous group of people defined largely by their pottery design style.

Linguistically, the origins are clear. Lapita is just one chapter in the Austronesian diaspora.

Austronesian is unusual among language families: it’s extremely large, with more than a thousand modern languages, and it’s the most widely dispersed in the world (until the post-Columbus expansion of Indo-European languages). It extends from Madagascar to Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, and spans over 70 degrees of latitude, from Hawaii to the southern tip of New Zealand. All modern Polynesian languages are daughters of this family.

Like drawing up an evolutionary tree from the genetic diversity found in living organisms, modern languages can also be used to reconstruct ancestral proto languages and their relationships to each other. When this is done, Taiwan emerges as the most likely origin of Austronesian.

The archaeological record supports the notion that the Lapita journeys were a deliberate effort to colonise new land. Lapita sites discovered so far are close to the beach and, in Near Oceania they are mostly on small off-shore islands. The choice of coastal sites also suggests a dual subsistence economy, relying on both fishing and agriculture. Excavations have also revealed that the Lapita toolbox included a range of fish hooks made from shell, nets, spears and different types of stone adzes.

Intriguingly, the most complex patterns of decoration are associated with the oldest sites, and plain ware and more simply decorated pots make up a growing proportion of assemblages found in later settlements.

Why the Lapita might have abandoned the rituals and practices they had so treasured remains a mystery. Matthew Spriggs says once you move beyond Samoa and Tonga, the area of sea compared to the area of land “increases massively and there was probably a threshold of relatively easy travel back and forth”.

- environment

- Austronesian languages

- Lapita pottery

- Pacific migration

- Polynesian ancestors

- archaeology

- burial rituals

- human migration

To embed this content on your own webpage, cut and paste the following:

<iframe src="https://www.rnz.co.nz/audio/remote-player?id=201766015" width="100%" frameborder="0" height="62px"></iframe>

See terms of use .

Recent stories from Our Changing World

- Summer 34 – Three decades of albatross research

- Taking on water - marine protection in Aotearoa

- A tale of two islands – erect-crested penguins

- The mystery of how godwits sleep in flight

- The stuff of life - Carbon capture in our ocean ecosystems

Get the RNZ app

for easy access to all your favourite programmes

Subscribe to Our Changing World

Podcast (MP3) Oggcast (Vorbis)

Terracotta fragments, Lapita people

Terracotta fragments, Lapita people, c. 1000 B.C.E., red-slip earthenware, Santa Cruz Islands, south-east of Solomon Islands ( Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland , CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Archaeologists get very excited when they find pieces of Lapita pottery. Why? Because the sequential depositing of potsherds (fragments of pottery) in an easterly direction across the island groups of the Pacific has become the pivotal evidence that tells the extraordinary story of the peopling of the vast Pacific Ocean. Pieces of the distinctive red-slipped pottery of the Lapita people have been recovered from sites spanning thousands of miles across the Pacific from the outer reaches of Southeast Asia, through the island groups often referred to as Micronesia and Melanesia , and into the central Pacific and Polynesia .

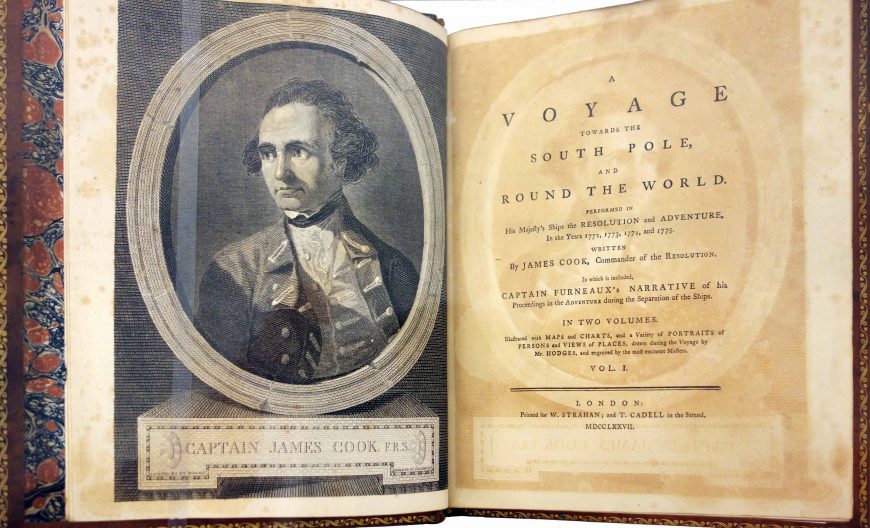

Captain James Cook, A voyage towards the South Pole, and round the World. Performed in His Majesty’s ships the Resolution and Adventure, in the years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775 (London: Printed for W. Strahan; and T. Cadell in the Strand. 1777) (photo: Daderot CC0 1.0)

An archaeological puzzle

Though Pacific Islanders have their own richly detailed historical accounts of the exploration of their “sea of islands,” European speculation about how and when the Pacific was populated began with James Cook and other European voyagers of the Enlightenment era (1700s). [1] Theories based on thin historical conjecture proliferated in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, often at odds with Islanders’ own knowledge systems. At first it was thought that the inhabitants of what is now known as Near Oceania colonized the islands southeast of the Solomon group, now referred to as Remote Oceania (see map below). It was not until archaeologists began to undertake stratigraphic archaeology in the Pacific from the 1950s onwards that this idea was debunked—mostly due to evidence provided by the multiple archaeological sites where Lapita pottery has been found.

Near Oceania and Remote Oceania, underlying map © Google

Archaeologists now believe that, somewhere between 4,000 and 3,500 years ago, a group of people who had sailed from the area around Taiwan in Southeast Asia arrived by canoe to the beaches of the Bismarck Archipelago. The new arrivals, who we now know as the Lapita people (named for the beach on the island of New Caledonia where a large number of pottery sherds were found), spoke a different language than the people they would have encountered there. These local people had been living on the large island now known as New Guinea and the surrounding islands for between 60,000 and 40,000 years. [2] Aside from their language and different genetic stock, the Lapita were different to those they encountered because they had sophisticated seafaring and navigation capability—and they manufactured and decorated ceramics in very particular ways. We can only theorize about the political and environmental pressures that drove these people to set out to sea in search of new places to live. Nevertheless, the pieces of broken but stylistically related potsherds distributed across thousands of miles of islands, laid down in datable stratigraphic layers, have revealed important information about the ancestors of the contemporary peoples of the central Pacific.

Terracotta fragments, Lapita people, red-slip earthenware, Watom Island, Bismarck Archipelago (photo: Merryjack CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Travel and trade

Lapita pottery was shaped by hand, and perhaps using a paddle-and-anvil technique to thin the walls, but without the aid of a potter’s wheel. It is low-fire earthenware (no evidence of Lapita kilns have been found). This means that the dry clay pots would likely have been placed in open fires to harden—the descendants of the Lapita people in Fiji and other areas still make pottery in this way. There is some geographical variation in the shapes and sizes of the pottery but most were simple bowls, some had pedestal feet, and others were flat-bottomed vessels. We know that the pottery was generally not used for cooking because carbon residues are not normally found on the potsherds. Rather, the evidence suggests that much of the pottery was used for serving food, while larger vessels were likely used for storage.

Near Oceania, underlying map © Google

The makers of the Lapita pottery blended clay with a particular type of sand. The sand was needed as a temper to make the vessels more durable during firing. Both the clay and sand are only found in certain areas of the Pacific. The islands in Remote Oceania are far less diverse in terms of geology than those in Near Oceania, and only a limited number of island locations had deposits of the clay used to make the pottery.

Analysis of the composition of the sherds has revealed valuable information about where the raw materials came from. The archaeologist Terry Hunt has analyzed a large number of potsherds found by the archaeologist Patrick Kirch at Talepakemalai and other Mussau Lapita sites (see map above). The Mussau islands, which are mostly limestone, are one of the island groups with very little clay. Hunt showed that a large number of the potsherds found there had been made from materials brought from other places, indicating that either the raw materials or perhaps the pots themselves had been imported. This reveals that the Lapita people had the means and the need to travel and trade across significant ocean stretches—their “sea of islands.” Perhaps, the most remarkable thing about the Lapita pottery sherds is that despite the remaining sherds being found thousands of miles apart, they share a formal and discernible design grammar that archaeologists can analyze. In fact, it is the decoration of Lapita pottery that holds the greatest amount of information for archaeologists.

Terracotta fragments, n.d., Lapita people, red-slip earthenware ( Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland , CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

A design grammar

The decoration of the pottery consists of stamped and incised motifs that adhere to a very regular, structured, and repeated set of specific patterns. The motifs were applied to the surface of the vessel with a small dentate (tooth-like) stamp and/or drawn free-hand with a sharp edge of some sort. The pattern stamps used included both linear and curved shapes of various lengths, as well as round forms. Once a pot was decorated, a paste of white coral lime was applied to the pattern which had the effect of making the delicate patterning stand out against the reddish-brown clay. Types of patterns range from simple to complex geometric forms, and include anthropomorphic face designs (image, top of page) found on Talepakemalai in the Mussau island group (see map above). The anthropomorphic pattern was a characteristic of early Lapita pottery, and is not present on pottery found in the upper (and therefore newer) archaeological layers of sites further east in Polynesia.

Archaeologists contend that those responsible for decorating the pots used a very restricted range of motifs and combined these in specific ways on particular areas of the pots. In other words, the ancient people who decorated the pots followed the rules of a defined design system. As Kirch notes “although we may never know what was in the minds of those potters and design-makers, we can understand in a more formal or structural sense their system of art and design, and use this as a tool for tracing the history of Lapita pottery in time and space.” [3]

Painted Barkcloth ( Masi kesa ), late 19th–early 20th century, Lau Islands, Fiji, 85.1 x 419.1 cm ( Metropolitan Museum of Art ) “The repeating geometric motifs of many tapa cloths at times resemble those seen on pottery produced by the Lapita peoples, who were the ancestors of present-day Polynesians.” ( object page )

A major breakthrough in the analysis of the Lapita design system came in the 1970s when Māori archaeologist Sydney Moko Mead developed a coherent formal system to categorize the design elements and motifs found on Lapita pottery. Mead’s system drew inspiration from linguistic analysis and has a set of components that form the building blocks of the “grammar” of the Lapita design system. These include: design elements, motifs, zone markers, and design fields. Even though the design system changed incrementally through time and within specific geographical areas as people moved across the Pacific, the underlying structural patterns and rules of the system remained the same. From an analytical point of view, the systemized grammar of design has meant that potsherds found in one site can be categorized and compared with others found in multiple other sites to provide evidence of the movement of the Lapita people in particular timeframes. What’s more, vestiges of the design motifs and the grammar of the system are apparent in contemporary tattooing, barkcloth decoration and other art forms throughout contemporary Remote Oceania (image above).

Islands east of Bismarck archipelago settled by the Lapita people, underlying map © Google

An extraordinary story

As the Lapita people moved east past the Bismarck archipelago they likely reached the Samoan and Tongan Island groups around 800 B.C.E. They then paused for 1200 years when another phase of colonization began, and people headed toward the most distant reaches of the Polynesian triangle . People arrived in Hawai‘i by c. 1000 C.E., and Rapa Nui/Easter Island and Aotearoa/New Zealand by about 1200 C.E. For the most part, the further east the Lapita people headed, the simpler their patterns became. The most recent potsherds, found in the most easterly and south westerly locales, are minimally decorated. It seems that within a couple of hundred years of arriving in what are now Samoa and Tonga (see map above), Lapita pottery and its distinctive design decoration had all but disappeared. When Europeans arrived in the Pacific in the 1700s and 1800s, the ocean going long-distance seafaring canoes were gone, but the knowledge of distant islands and oral histories of voyaging remained. Archaeologists are still actively working to untangle the history of this early pottery, and with each successive discovery, to add to the extraordinary story of the Lapita people.

[1] In his seminal essay “ Our Sea of Islands ,” Tongan scholar Epeli Hau’ofa asserted “There is a gulf of difference between viewing the Pacific Islands as ‘islands in a far sea” (as has been historically constructed by Europeans) to “a sea of islands.” Whereas the former emphasizes remoteness, the latter reinstates the ocean as a connector between all the people and islands of the Pacific; an oceanic highway in a region rich in resources. Epeli Hau’ofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” A New Oceania: Rediscovering Our Sea of Islands (Suva, Fiji: The University of the South Pacific, 1993), pp, 2–16.

[2] Patrick Vinton Kirch, “Peopling of the Pacific: A Holistic Anthropological Perspective,” Annual Review of Anthropology , volume 39 (2010).

[3] Patrick Vinton Kirch, The Lapita Peoples: Ancestors of the Oceanic World (Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1997), p. 126.

Bibliography

Lapita pottery with a human face

Lapita pottery on Metropolitan Museum of Art Timeline of Art History

Pottery making Fiji style

Patrick Vinton Kirch, “Peopling of the Pacific: A Holistic Anthropological Perspective,” Annual Review of Anthropology , volume 39 (2010), pp. 131–48.

Patrick Vinton Kirch, On the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).

Patrick Vinton Kirch, The Lapita Peoples: Ancestors of the Oceanic World (Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1997).

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Recent Photos

- The Commons

- Flickr Galleries

- Camera Finder

- Flickr Blog

- The Print Shop

- Prints & Wall Art

- Photo Books

- Stats Dashboard

- Get Auto-Uploadr

The Lapita Voyage Project I have always been fascinated by the Pacific cultures and the multitude of different type of canoes associated with them, in particular those carved within the Polynesian Triangle, Micronesia and Melanesia. So my interest, as a canoe modeler, does not simply rest in re-creating ancient types of Hawaiian canoes or reproduce the Hokule’a, but also to make models of some of the most amazing vessels that were constructed long ago within Oceania but have all but disappeared from its islands . More over, and this is always a particular and exciting challenge, I love to reproduce those larger voyaging canoes that have recently been built in the South Pacific. What ever the type of canoe I decide to reproduce; it is a task that requires in depth research and my lasting gratitude goes towards the late Herb Kane without whom we would not be able to know the beautiful shape of some Oceanic canoes. I also like to refer to the works of Hadden & Hornell as well as the beautifully illustrated volumes of Jean Neyret . The internet has replaced books and it is while reading online about the Lapita culture, which is at the root of Polynesian culture and famous for its pottery style, that I became interested in the Lapita Voyage Project whose principals were Klaus Hympendahl, a German author and photographer, explorer, sailor and ship architect of catamarans James Wharram, and Hanneke Boon who is Wharram’s design partner. The objective of the Lapita Voyage Project was to built two double hull canoes and sail them from the Philippines to the island of Anuta , a route of 4,000 miles which is believed to be the one used by the Lapita culture during their expansion eastwards. The name of the two canoes would be ‘Child of the Sea” or “TAMA MOANA” and they would be based on the construction style of Hawaiian voyaging canoes but also incorporate design principles from the island of Anuta and Tikopia. Their size would be 37’9” in total length with beam overall 14’11”. The model was executed not with the help of a studyplan but by extrapolating sizes and scales on the basis of 3 original sizes; lenght, width of beams, height of hulls. The model was on exhibition at the Gallery Martin & Macarthur , Ala Moana, Honolulu, until it was sold. To see more check www.hawaiiancanoes.com

Hanneke Boon in a Wharram designed Tiki catamaran

James Wharram and Klaus Hympendahl aboard James catamaran SPIRIT OF GAIA

[ Click on one of the pictures to enlarge ]

James Wharram, Hanneke Boon and Klaus Hympendahl (2008)

For more than 50 years, James Wharram has been designing, building and sailing catamarans. 10,000 people have bought his designs ranging in size from 21’ to 63’. They are all based on the principles of Polynesian double canoes.

Hanneke Boon has been Wharram’s design partner for 30 years. Her artistic/practical input into the designs has made Wharram’s concepts more accessible to the public.

From 1995 to 1998 Wharram and Boon sailed around the world on their 63’ (19m) catamaran SPIRIT of GAIA studying Indo-Pacific canoe design, visiting the island of Tikopia.

Klaus Hympendahl is a well-known German author of maritime books and articles.

While sailing round the world (1986 - 1990) he visited Tikopia. In 2003 he raised funds to rebuild the small island-clinic (the only western building) which was destroyed by cyclone Zoe in 2002.

Klaus Hympendahl sadly died suddenly in February 2016. The Lapita Voyage would not have been possible without Klaus’ organisational work and efforts to raise the money to build the boats.

» [ back to top ]

Copyright © 2009 Klaus Hympendahl . All rights reserved.

James Wharram Designs

Search Our Site

- Self Build Boats

- Professionally Built Boats

- Choosing a Boat

- How We Design

- Photo Gallery

- Video Gallery

- Articles & Blogs

- Wharram World

Lapita Voyage Appeal

A month from today Hanneke and I will begin our flights out to Andy Smith Boatworks’ yard in the Philippines. A month later, on November 1st we will begin our Lapita Voyage , 3800Nm, south through the Moluccas, along the North coast of New Guinea, passing through the Solomon Islands and on to Tikopia and Anuta, where we will present the two boats to the islanders so they can restart their seafaring tradition.

The Lapita Voyage project has grown from a simple ‘donating two ships to the islanders’ to a major archaeological expedition. This voyage is providing a vehicle for various archaeologists/scientists with interests in the Polynesian migrations and Lapita culture to carry out studies impossible to do from a land based expedition. Five scientists will be sailing on different legs of the voyage. Others, who cannot leave their posts at their universities or archaeological digs, are participating from a distance. The expedition will be filmed for television.

Last week I realised a further dimension. Through an email from a teacher in Honiara, we discovered there are several colonies of Tikopians in the Solomon islands, in fact as many or more Tikopians live outside Tikopia as on the island (which can only support approx. 1200 inhabitants). There are a large number Tikopians in Honiara, who are keen to welcome the ships. These ships are a symbol of their island identity. We will try to visit the other Tikopian colonies along the route of the voyage. The two Tama Moanas will be the connection between all these scattered, but related people (called ‘wontoks’ in their culture).

As I get older I am beginning to realise what man my father was and his influence on me. Like many sons, in my youth I did not value his abilities and qualities, but as I look at myself now, I realise that unconsciously I absorbed many of his principles. One of his principles was ‘rely on yourself’, which is why I never sought sponsorship for my projects. Only now, with the Lapita Voyage project, I feel this advice does not apply to all situations.

This project would not be happening without the sponsorship that Klaus Hympendahl managed to obtain. He has been responsible for raising money and acquiring gifts of equipment, by going out and asking the German public and businesses for help. He set up a charitable association ‘Help Tikopia und Anuta e.V.” into which payments were made by people that in return get a chance to sail on the boats. This system has brought in all the money needed to build the two boats.

So, we are nearly there. The boats are paid for and will soon be finished, now there remains a need of some more funds for the voyage itself, all those little things that make a voyage successful. Klaus still has to buy the iridium telephone through which we can regularly update the website, so everyone can follow the voyage as it is taking place. Maybe someone has one to donate?

I feel it is not too late to appeal to the Wharram World and other multihull enthusiasts for sponsorship/donations, big ones are welcome, small ones in large numbers will also be of great help. We modern multihull sailors do owe something to the descendants of the Stone Age originators of our craft.

Donations should be made by bank transfer to:

Help Tikopia und Anuta e.V. Dresdner Bank AG IBAN: DE67 3008 0000 0363 6100 00 BIC: DRES DE FF 300

Euro cheques, made out to ‘Help Tikopia und Anuta e.V.’ should be sent to Klaus Hympendahl, Wildenbruch Stasse 75, 40545 Düsseldorf, Germany. Do not send cheques in other currencies, as these incur large bank charges.

Help Tikopia und Anuta e.V. is a charitable association and donations are therefore tax deductible. Please contact Klaus if you would like an official receipt. Email: [email protected]

- James Wharram

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Architecture News

Moscow Launches New Smart City District as a Living Lab

- Written by Eric Baldwin

- Published on December 13, 2018

The government of Moscow has begun developing an existing district in the city to test nearly 30 new ‘smart’ technologies for urban development. Home to over 8,000 people, the district is testing ideas on smart lighting, smart waste management, and smart heating. The city intends to evaluate what impact technologies bring to residents and adjust its urban renewal plan once the pilot is complete.

When creating a smart district, cities tend to choose new, empty or even abandoned areas to build a district from a scratch, which is faster, easier and more cost-efficient. However, Moscow authorities made the decision to create one in an already existing neighborhood to bring top tech solutions. In April 2018, authorities began implementing technologies in selected buildings situated in Maryino district on the southeast of Moscow . The district includes seven apartment buildings with different years of construction from 1996 to 1998. Each residential building has a different construction type that gives an advantage to pilot the technologies under various conditions.

Andrey Belozerov, Strategy and Innovations Adviser to CIO of Moscow explained: “We didn’t want to build a district from a scratch as a test bed far from real-world settings. Our aim was to test technologies in inhabited neighborhood so it allows us to see whether citizens get advantage of new technologies in their everyday tasks. When the pilot is completed we aim to adjust the city urban renewal plan, so Muscovites enjoy living in similar technology-savvy buildings around the city in the future”.

The smart district residents can access smart systems responsible for heating, lighting, and waste collection. In total selected residential buildings are equipped with twenty nine different smart technologies. As part of the project the first charging station for electric vehicles situated in residential district has been installed in Moscow – it has already become the most popular charging station for electric vehicles in the city. In addition, free Wi-Fi network is available on site. Each resident can install free mobile application to answer the house intercom when no one is around or open the door without a key. The project aims to improve quality of life and provide comfort and safety for residents.

- Sustainability

想阅读文章的中文版本吗?

莫斯科启动“智能小区”计划,将为8000人口提供智能家居生活

You've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Lapita Voyage (2008-2009) was the first sailing expedition that successfully followed a possible migration route of the ancient Polynesians out of SE Asia. Starting in the Philippines, passing through the Molucca Islands, following the north side of the second biggest island on earth, New Guinea, sailing through the archipelago of the Solomon ...

The Lapita Voyage, led by German, Dutch and English, with its unique opportunities for research, was a major scientific expedition, but also a fantastic sailing adventure. The two boats met squalls, storms and days of calms. ... Many firms donated materials and equipment to this charitable project, but the major part of the money for building ...

The voyage to Tikopia. Once the canoe is finished and had sailing trials she is ready to make the voyage to Tikopia. The route of this voyage is the same as the Polynesian ancestors made 3000 years ago and follows the 'Lapita Trail'. This sailing voyage in its own right is of enormous interest to experimental archaeology.

The Lapita Voyage project is to build two 11m Tama Moana double canoes. They will be built in the Philippines, at a yard experienced in building my double canoe designs. We will then sail the two canoes, one skippered by Hanneke and I, the other by Klaus Hympendahl, from there 3800Nm to the islands of Anuta and Tikopia, following the ancient ...

The trip, called "Lapita-Voyage", will be crewed by two Polynesians, two scientists, a cameraman and the initiators James Wharram, Hanneke Boon (catamaran-designers) and Klaus Hympendahl (author and organiser of the project). At the end of the voyage the two double canoes will be presented to the inhabitants of the small Polynesian islands of ...

At this first conference, my design partner, Hanneke Boon, and I gave a paper on our proposed Lapita Voyage, ... "We are interested in the Amatasi 27 as a starter project to reintroduce sailing into much of the outer islands of the Federal States of Micronesia. The inter-island transportation system is almost non-existent and we are losing ...

Here they stayed for at least a century before making long-distance open sea voyages to make first landfall on the Remote Oceanic ... M. in Report on the Lapita Homeland Project (eds Allen, J ...

The Lapita Voyage was a charitable project which began in the first week of November 2008, when 2 double canoes, based on the ancient Polynesian canoe form o...

The 'Lapita Voyage' was the first exploration by ethnic sailing canoe craft of one possible migration route into the Central Pacific from SE Asia. It was the first alternative voyage by double canoe to Thor Heyerdahl's Kon-tiki raft voyage from South America in 1947, whereby he tried to proof the Polynesians had arrived from South America

The objective of the Lapita Voyage Project was to built two double hull canoes and sail them from the Philippines to the island of Anuta, a route of 4,000 miles which is believed to be the one used by the Lapita culture during their expansion eastwards. The name of the two canoes would be "Child of the Sea" or Tama Moana and they would be based ...

On 26th October 2008 the two boats of the 6000km-long Lapita Voyage, Lapita Tikopia and Lapita Anuta, slipped into the water without a hitch. ... The Lapita Voyage project. From the initial discovery of the Polynesians, their lifestyle and knowledge, which have enriched and lightened Western Society, have moved one way, from 'them' to 'us ...

The serendipitous discovery soon led to a major project which unearthed not just more pottery but human remains. More than a decade later, the site at Teouma is now famous among Pacific archaeologists as the oldest Lapita cemetery, reaching back three millennia to the very beginning of an epic voyage of discovery.

An extraordinary story. As the Lapita people moved east past the Bismarck archipelago they likely reached the Samoan and Tongan Island groups around 800 B.C.E. They then paused for 1200 years when another phase of colonization began, and people headed toward the most distant reaches of the Polynesian triangle.

Lapita Voyage Logs 2nd November 2008 James Wharram On 26th October 2008 the two boats for the 4000Nm long Lapita Voyage, 'Lapita Tikopia' and 'Lapita Anuta', slipped into the water without a hitch. Blessed with a few words and a splash of coconut milk from expedition leaders Klaus Hympendahl and myself they were heaved down a beautiful white-sand beach and into the Pacific.

The objective of the Lapita Voyage Project was to built two double hull canoes and sail them from the Philippines to the island of Anuta, a route of 4,000 miles which is believed to be the one used by the Lapita culture during their expansion eastwards. The name of the two canoes would be "Child of the Sea" or Tama Moana and they would be based ...

The Lapita Voyage Project I have always been fascinated by the Pacific cultures and the multitude of different type of canoes associated with them, in particular those carved within the Polynesian Triangle, Micronesia and Melanesia. So my interest, as a canoe modeler, does not simply rest in re-creating ancient types of Hawaiian canoes or reproduce the Hokule'a, but also to make models of ...

Klaus Hympendahl is a well-known German author of maritime books and articles. While sailing round the world (1986 - 1990) he visited Tikopia. In 2003 he raised funds to rebuild the small island-clinic (the only western building) which was destroyed by cyclone Zoe in 2002. Klaus Hympendahl sadly died suddenly in February 2016.

On 22 March 2024, a terrorist attack which was carried out by the Islamic State (IS) occurred at the Crocus City Hall music venue in Krasnogorsk, Moscow Oblast, Russia.. The attack began at around 20:00 MSK (), shortly before the Russian band Picnic was scheduled to play a sold-out show at the venue. Four gunmen carried out a mass shooting, as well as slashing attacks on the people gathered at ...

The Evolution Tower (Russian: Башня "Эволюция", tr. Bashnya Evolyutsiya) is a skyscraper located on plots 2 and 3 of the MIBC in Moscow, Russia.The 55-story office building has a height of 246 metres (807 ft) and a total area of 169,000 square metres (1,820,000 sq ft). Noted in Moscow for its futuristic DNA-like shape, the building was designed by British architect Tony Kettle in ...

A month later, on November 1st we will begin our Lapita Voyage, 3800Nm, south through the Moluccas, along the North coast of New Guinea, passing through the Solomon Islands and on to Tikopia and Anuta, where we will present the two boats ... The Lapita Voyage project has grown from a simple 'donating two ships to the islanders' to a major ...

The government of Moscow has begun developing an existing district in the city to test nearly 30 new 'smart' technologies for urban development. Home to over 8,000 people, the district is ...

Ginza Project OOO Jun 2015 - Aug 2015 3 months. New York, United States Mari Vanna NYC Learned high-quality service standards ... As momentum builds towards the inaugural voyage of # ...