- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

29 Travel and Travel Writing

Maria Pretzler is Lecturer in Ancient History at Swansea University.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Greek travellers tried to take their city with them: travel is typically conducted as a civic act, one justified and defined by one's tie to the city: trade, for example, or martial aggression, or colonization. This article discusses the range of travel experiences reflected in surviving literature. The study of ancient travel focuses on the process of travelling, on individual travellers' movements and their reactions to particular journeys and places. The evidence is therefore mainly literary, with valuable additions from epigraphic sources. The remains of sites that were particularly attractive to ancient travellers, depictions of their means of transport, shipwrecks, and traces of ancient roads can add further information. Greek travel literature had a strong influence on early modern geography and ethnography, and it still has an impact on how people understand the Greek world.

G reeks liked to think about their world by tracing colonists' movements from the old motherland to distant Mediterranean shores: they considered mobility as a crucial factor in defining what, and who, was essentially Greek. Myth and epic poetry set the scene by depicting an earlier age of travellers, be it the Achaeans on their overseas campaign against Troy and then on their tortuous journeys to return home, or adventurous heroes such as Heracles or Jason and the many founders of Greek cities everywhere. For us, the Odyssey in particular provides a wide range of responses to the experience of travelling overseas in the crucial period when Greek colonization began to shape the ancient Mediterranean as we know it. In Odysseus' tales we encounter a variety of travellers engaged in friendships, diplomacy, and marriage outside their own community, and many people risking adventures for gain through trade, piracy, war, or increased knowledge. Others were forced to leave their home, either displaced as slaves or seeking refuge after conflict. Odysseus, always longing to go home to Ithaca while experiencing both the benefits and the horrors of a long overseas journey, shows how the image of the traveller could be reconciled with that other crucial aspect of Greek identity, a close and lasting connection to one's polis. Many did, however, not return home: by the end of the archaic period we find hundreds of colonies, new poleis, around the coasts of the Mediterranean, and some Greeks sought opportunities well beyond the regions settled by colonists.

It is possible to document complex and dense connections between places and regions around the ancient Mediterranean and beyond (Horden and Purcell 2000 ), but most of the evidence for high levels of connectivity in the ancient world does not provide information about the actual process of travelling. The general and vague information derived from imported objects found on archaeological sites suggests the movements of people without offering much insight into the mode or direction of particular journeys. Nevertheless, the general observation that travel was not an exceptional activity in the ancient world should inform our approach to ancient texts dealing with travel experiences. The study of ancient travel focuses on the process of travelling, on individual travellers' movements and their reactions to particular journeys and places. The evidence is therefore mainly literary, with valuable additions from epigraphic sources. The remains of sites which were particularly attractive to ancient travellers, depictions of their means of transport, shipwrecks, and traces of ancient roads can add further information.

Much of what we know about ancient travel concerns the small, eloquent elite that generally dominated the ancient literary record. Throughout antiquity travel was a part of life for wealthy individuals who were involved in the affairs of their community. They were particularly active in maintaining contacts beyond their community, from the elaborate guest-friendships of the Homeric epics to embassies to the emperor in the Roman period. Throughout antiquity, members of the elite relied on widespread contacts which could include acquaintances who were not Greek. Travelling as we see it in most ancient texts was expensive, because eminent people travelled in grand style, with numerous attendants and considerable luggage (Casson 1994 : 176–8). Early Christian texts, particularly the Gospels, Acts, and some of St Paul's epistles, look beyond the small, wealthy elite and offer a different cultural perspective, but this valuable source-material has yet to be fully integrated with classical scholarship.

Information about the activities and routines of ancient travel has to be pieced together from disparate references in ancient texts, and the bulk of the evidence dates from the Roman period (Casson 1974 ; Camassa and Fasce 1991 ; André and Baslez 1993 ). The preferred mode of long-distance travel was by ship: not only was sea travel faster and more comfortable (e.g. Pliny, Epistles 10.17a; Casson 1974 : 67–8, 178–82), but few important Greek sites were located far from the sea. Journeys on land probably often meant walking, even for long distances, although wealthy travellers would use carriages. Mainland Greece at least had a dense road network suitable for vehicles which reached even remote, mountainous locations. Many of these roads date back to the archaic or early classical period and they were in use until the end of antiquity (Pikoulas 2007 ; Pritchett 1980 : 143–96). These practical aspects of ancient travel are rarely the focus of modern research, but they are crucial for our understanding of how ancient travellers interpreted their surroundings. The slow pace of ancient journeys facilitated intensive encounters with landscapes, sites, and local people, while ancient travellers were often less interested in the wider context of their location. Geographical overviews and accurate maps of large regions seem to have remained the domain of scholarly experts, while many travellers may have adopted a view which organizes the landscape along particular routes without paying much attention to a ‘global’ perspective (cf. the Peutinger Table and Pausanias, with Snodgrass 1987 : 81–6).

Trade, war, and the search for opportunities may have accounted for a majority of individual journeys in antiquity (Purcell 1996 ), but these activities are rarely at the centre of attention. Journeys made for the sake of travelling, usually for the spiritual and intellectual benefit of a particular individual, account for much of the information about travel experiences that can be found in ancient texts, and modern scholarship reflects this emphasis on what we might call ‘cultural travel’. Early Greek travellers were often engaged in new discoveries, encountering unknown regions and strange cultures. The exploration by Greeks of regions around the western Mediterranean and the Black Sea may be reflected in the epic tradition, particularly the Odyssey , although it came too early to leave credible traces in the literary record. Areas beyond the Mediterranean remained largely unknown well into the Hellenistic period. The Atlantic coasts of both Europe and Africa were occasionally visited by explorers who recorded their observations, for example Hanno and Pytheas of Massalia (Carpenter 1966 ). Egypt and the Middle East had always been more accessible to the Greeks, not least because there they encountered highly developed cultures that were much older than their own.

By the end of the archaic period Greeks had travelled widely and extended the boundaries of their known world: from Egypt they had reached the upper Nile Valley and brought news of regions further south, and, from the sixth century, knowledge about distant regions of the East as far as India could be obtained through good connections with the Persians. Herodotus criticizes the theories about the shape of the earth inferred from such information by the geographical theorists of sixth-century Ionia, but he also testifies to the usefulness of maps created in this period and he includes geographical information about distant regions in his own work (Herodotus 4.39, 5.49; Harrison 2007 ). Alexander's conquests in the East and the expansion of the Roman empire, especially in western Europe, provided the Greeks with opportunities to reach hitherto unknown regions and to obtain more detailed geographical information (Polybius 3.59; Clarke 1999 ). The edges of the earth, however, remained a matter of legends about unusual peoples and cultures and wondrous natural phenomena (Hartog 1988 : 12–33; Romm 1992 ). All surviving ancient explorers' tales have been subjected to intense scrutiny to match them to actual regions and cultures. Recent scholarly attention, however, has been focused on the particularly Greek perspective on alien cultures which often describes strange people in terms of stark contrasts with what was familiar to the writer and his audience. In fact, authors dealing with ‘barbarians’ often seem more concerned with exploring their own culture than with giving an accurate picture of a distant region and its people. (Hartog 1988 : 212–59).

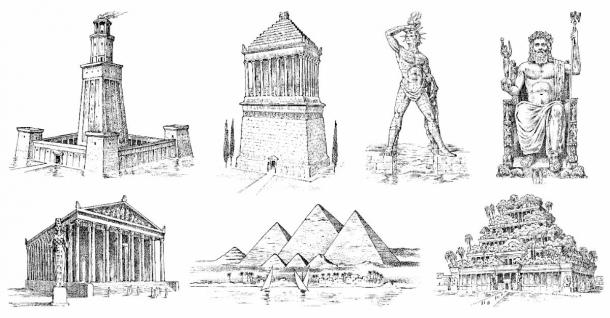

Most ancient travellers stayed within the familiar confines of the Mediterranean, but there was plenty of scope for ‘cultural’ travel in the Greek world and among its immediate neighbours. Educated Greeks would embark on sightseeing tours to visit famous places, for example a number of historical sites in mainland Greece, including Athens, Olympia, Delphi, and perhaps Sparta, some of the cultural centres of Asia Minor such as Ephesus or Pergamon, and Ilium as the main location of the Trojan War. Egypt, with its spectacular ancient sites (Casson 1974 : 253–61), was also an attractive destination. These sightseeing activities are sometimes described as ancient tourism, but this term is rather misleading because it invites analogies with the seasonal mass movements of today. The Grand Tours of wealthy Europeans of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would be a more appropriate analogy (see Cohen 1992 ). Most visitors were particularly interested in ancient monuments with historical connections, artworks by famous artists, and sights that could be classified as curiosities. In most places with important historical monuments a visitor could employ professional tourist-guides to explain the sights, and wealthy travellers could apparently rely on members of the local elite to provide a tour appropriate for refined tastes and educated interests (as Plutarch does in his work On the Pythia's Prophecies ; and cf. Jones 2001 ).

In recent years ancient pilgrimage has attracted particular interest (Hunt 1984 ; Dillon 1997 ; Elsner 1997 ; Elsner and Rutherford 2005 : esp. 1–30). The applicability of this term to the activities of ancient travellers is contentious (Morinis 1992 : 1–28; Scullion 2005 : 121–30), but valuable interpretations of ancient texts have emerged from this line of enquiry. Throughout antiquity many sanctuaries saw large numbers of visitors, and some festivals could attract considerable crowds. Many people undertook such visits on their own initiative, but states also maintained regular official links with specific sanctuaries beyond their borders. The concept of pilgrimage invites new enquiries into the function and meaning of such journeys, especially as a means of defining identities and collective memories. Pilgrimage can also be a useful category in assessing ancient attitudes to historical sites. After all, the classical texts played a dominant role in the lives of educated Greeks and determined their approach to places that were in some way linked to the literary tradition. Historical sites, such as important battle-fields or places that played a crucial role in the Homeric epics, allowed visitors to explore localities with which they were intimately familiar from their reading since childhood, and which were part of a common Greek consciousness. Visits to such places could therefore have a profound effect which cannot easily be distinguished from a spiritual or religious experience (Hunt 1984 ). This approach to spiritual, cultural, and emotional aspects of pagan visits to significant places also allows a new evaluation of Christian pilgrimage in late antiquity (e.g. Egeria), by considering it in the context of earlier, pre-Christian traditions (Hunt 1982 ; Holum 1990 ).

Travelling was seen as an important source of knowledge and wisdom, and it was closely linked to the ideals of Greek culture and education ( paideia ) (Pretzler 2007 b ). A traveller could learn by seeing and experiencing different places and civilizations for himself, and he might gain access to information which was not available in Greece. The Greeks were aware that some civilizations were far more ancient than their own, and they assumed that in some countries, for example Egypt, Mesopotamia, or India, travellers might be able to acquire considerable knowledge, particularly about the remote past. There were many legends about the extensive journeys of famous sages such as Solon or Pythagoras, echoed by later traditions about the adventures of Apollonius of Tyana, or Dio Chrysostom's claims about his own wanderings while he was in exile (Hartog 2001 : 5, 90–1, 108–16, 199–209). In the Roman period, many aspiring young men from all over the Roman world travelled to acquire a Greek education: they would move to one of the leading cultural centres such as Pergamon, Athens, or Smyrna to study with a distinguished sophist. Prominent intellectuals could enhance their reputation by travelling to give lecture tours and to compete with their peers (Anderson 1993 : 2–30). Educated Greeks were therefore expected to be acquainted with famous cities and sites, and such personal knowledge influenced intellectual debates and texts. Experience gained through travelling became particularly important to enhance the credibility of arguments and reports. Authors often stress that they have personally seen places or witnessed events they are describing, and such claims of autopsia became a standard literary topos, particularly in historical and geographical works (e.g. Thucydides 1.1; Strabo 2.5.11; Polybius 3.4; Nenci 1953 ; Lanzillotta 1988 ; Jacob 1991 : 91–4).

While travelling and travel experiences play a crucial role in many ancient texts, there is no clearly defined genre of Greek travel literature. Modern examples of the genre often offer an insight into personal experiences on a journey, and they reflect reactions to strange landscapes, places, and people (Campbell 2002 ). Few ancient texts cover any of these aspects extensively, and a study of literary responses to travel experiences needs to include texts which touch upon the subject although they belong to different genres. There is no comprehensive modern study of Greek travel writing, and the re-evaluation of relevant texts as travel literature is a relatively recent phenomenon (e.g. Elsner 2001 ; Hutton 2005 ; Roy 2007 ); much work remains to be done in this field. As far as we can tell, the expectations of ancient readers of travel texts differed considerably from those of their modern counterparts. Few ancient writers provide a clear sense of the topography of a place, and they rarely attempt to create a comprehensive image of a location that would allow readers to visualize what the traveller has seen. In fact, ancient travel writers are usually very selective about what to report: particular features of a landscape are usually only mentioned if they represent a curiosity or if they are relevant to the author's aims, for example sporadic topographical details in a historian's account of a battle. Detailed descriptions of objects were the subject of rhetorical exercises ( ekphrasis ), and landscape descriptions play a particular role in pastoral poetry, but they rarely take up much space in ancient travel accounts (Bartsch 1989 : 7–10; Pretzler 2007 a : 57–63, 105–17).

Ancient travel writing (in the widest sense) can be roughly divided into two categories: on the one hand there are accounts of particular journeys, and on the other hard there are texts which present facts about places or cultures without discussing the process of travelling. The tradition of such ‘factual’ geographical texts was traced back to the ‘Catalogue of Ships’ in the Iliad (2.484–760; cf. 2.815–77), which provides a list of Greek cities and tribes in a roughly geographical order. The earliest geographical texts probably took the form of periploi (e.g. ps. -Scylax), essentially seafarers' logs describing coastlines with important places and landmarks, or stadiasmoi which listed paces and distances along overland routes (Giesinger 1937 ; Janni 1984 : 120–30). Hecataeus' Periodos Gēs developed this genre further by combining a periplous -style description of the world with a scientific discussion of the shape of the earth and the layout of the continents. Later geographers continued to rely on verbal descriptions of coastlines and regional topographies which were never fully superseded by maps (Janni 1984 : 15–19; Jacob 1991 : 35–63). As Strabo shows, geographical works could include information about the landscape, history, and culture of particular places. Texts dealing with particular regions, for example local histories (e.g. Atthidography, Arrian's Bithyniaca ), could go into more detail and would usually rely on an intimate knowledge of landscape, monuments, and local traditions.

Most descriptions of regions and sites were probably mainly interested in historical monuments, religious sites, and significant artworks, not unlike the ‘cultural’ travel-guides of today (Bischoff 1937 ; Hutton 2005 : 247–63). Only two such works survive, Lucian's On the Syrian Goddess , a description of the sanctuary of Atargatis in Hierapolis which is clearly not meant entirely seriously (Lightfoot 2003 ), and Pausanias' Periēgēsis Hellados , ten books describing the Peloponnese and a part of central Greece which represent the longest extant ancient travel text (Habicht 1985 ; Alcock, Elsner, and Cherry 2001 ; Hutton 2005 ; Pretzler 2007 a ). Pausanias, a Greek from Asia Minor carried out extensive research between about 160 and 180 ce , but he rarely refers to his own travel experiences, probably in order to maintain his credibility as an objective observer. Pausanias shows little interest in the life of contemporary communities or the natural landscape. Instead, he focuses on sites with a historical or religious significance, and he provides detailed information about the symbolic and cultural interpretations that Greeks could attach to the landscape. The Periēgēsis follows a long ethnographic tradition, and particularly Herodotus, but instead of reflecting on his own identity by contrasting it with the strange customs of barbarians, Pausanias applies his observations to the heartlands of the Greek world, and he presents an intensive study of the history and state of Greek culture in his own time. A fragment of an early Hellenistic description of Greece by Heraclides Criticus offers a very different view of the landscape of Attica and Boeotia (Pfister 1951 ; Arenz 2006 ). He adopts an often humorous and somewhat flippant tone to comment on the customs and character of contemporary people and on general conditions for a traveller. Heraclides also records his impressions of the landscape and the general appearance of the cities on his route: his approach to the landscape remains unique among the preserved ancient Greek travel texts.

It seems that authors who described places without discussing a particular journey found it easier to assert their credibility. Accounts of individual journeys had a long tradition, but such stories rarely allowed clear distinctions between fact and fiction. Heated discussions about the veracity of tales about distant regions show that ancient readers were aware of this problem, but their conclusions about particular texts often do not agree with modern opinions (e.g. Strabo 1.2.2–19; Romm 1992 : 184–93; Prontera 1993 ). Fictional travel accounts should therefore be included in any study of ancient travel literature because they add to the range of possible literary responses to travel experiences, even if they may not provide factual information about ‘real’ places or journeys. Greek travel writing begins with a fictional tale, namely the Odyssey , with its stories about monsters and incredible events (Jacob 1991 : 24–30; Hartog 2001 ). What is more, its main narrator, Odysseus, is clearly an unreliable reporter who tells untrue stories (‘Cretan tales’) about himself and his adventures, and the epic demonstrates how a traveller can construct false tales which will stand up to scrutiny. Odysseus therefore was a hard act to follow: in his wake no traveller reporting adventures in distant lands could be without suspicion, and many did indeed feel free to add fantastic details to their accounts. The earliest explorers' accounts usually took the form of a periplous which would include some details about specific adventures and discoveries (e.g. Hanno, Pytheas of Massalia). In the Roman period, Arrian revisited the genre and demonstrated its potential complexities: he reports his activities as governor of Cappadocia in a Periplous of the Black Sea , which also allows him to explore his own position as a Greek with multiple identities (Stadter 1980 : 32–41; Hutton 2005 : 266–71; Pretzler 2007 b : 135–6).

Few ancient travel accounts deal with emotional responses to a journey or the transforming impact of the experience on an individual's character, knowledge, or spiritual state. Aristides' Sacred Tales are unique in presenting the authors' personal perspective on his activities, including many journeys, in the pursuit of health and a special relationship with Asclepius (Behr 1968 : 116–28). Most texts dealing with such personal experiences are fictional, and can take the form of extensive accounts, for examples a trip to India in Philostratus' Life of Apollonius , or the Greek novels that usually send their main characters on convoluted journeys before they can settle down to live happily ever after (Morgan 2007 ; Rohde 1960 : 178–310). Some travel authors make no attempt to disguise the fact that their stories are invented, and this can lead to fresh perspectives on the experience of travel. For example, Apuleius' Golden Ass (cf. Lucian, Ass ) takes the opportunity to consider a journey from the point of view of a beast of burden, and it describes a spiritual transformation which turns the main character into a devout follower of Isis. The story also provides a rare chance to observe various travellers who are not members of the elite (Schlam 1992 ; Millar 1981 ). Lucian's fantastic stories ( Lovers of Lies, True Histories ) and other examples of ancient fiction can be seen as a humorous exploration of the many devices employed by travel writers to make their accounts believable (Ní Mheallaigh 2008 ).

Travel accounts could recover some credibility in the context of historiography: after all, Herodotus' Enquiries ( Historiai ) involved extensive travelling around the eastern Mediterranean, and autopsy remained crucial to enhance a historian's authority. Some journeys were themselves historical events, for example long military campaigns, and they inspired a new kind of travel account which owed much to historiography but could also follow some of the conventions of ancient adventurers' tales. Xenophon's Anabasis is the most extensive personal account of a specific journey that survives from antiquity, although the author never admits that he is in fact one of the main characters in the story. Xenophon includes specific information about distances, topography, flora, fauna, and local people, and he gives the impression that decades after the events he can draw on detailed memories, perhaps even a travelogue (Cawkwell 2004 ; Roy 2007 ). His perspective, however, is not that of an explorer whose main aim it is to describe a foreign region, but that of a historian who includes details about landscape and people when they are relevant to the events described. Alexander's conquests inspired a number of participants to write accounts which probably took the form of historical accounts in the mould of Xenophon's Anabasis (Pearson 1960 ). In the East, Alexander's military operations turned into a journey of exploration, and his scientific staff gathered reliable, factual information about areas which had hitherto been almost unknown to the Greeks (Strabo 1.2.1; 2.1.6). Well-founded knowledge could, however, be superseded by fantasy: if Strabo (2.1.9) is anything to go by, realistic reports about India did not have a lasting impact and were soon replaced by the old traditions about an exotic land full of strange wonders (Seel 1961 ; Romm 1992 : 94–109). Alexander's campaign became itself the subject of the Alexander Romance , which reinterpreted historical events in the tradition of myths and fictional adventure stories: in ancient travel writing, imagination could sometimes be stronger than reality.

Like Odysseus, Greek travellers are often unreliable witnesses of places and events they have seen, but their tales offer great insights into ancient perceptions of the world. Greek travel literature had a strong influence on early modern geography and ethnography, and it still has an impact on how we understand the Greek world. Since the Renaissance, western travellers who set out to discover the eastern Mediterranean relied on ancient texts to guide them to classical sites and to help them interpret the historical landscape. They also drew on similarities between the reactions of travellers in the Roman period and their own feelings about ancient sites and the loss of Greek culture. Ultimately, our understanding of antiquity owes much to ancient travellers who contributed their observations and interpretations to the definition of Greek culture and identity. The reception of ancient travel literature, especially of major texts such as Strabo or Pausanias, deserves attention, not least in the context of the development of our own disciplines, namely Classics, Ancient History, and Classical Archaeology.

Suggested Reading

The classic account of many facets of ancient travel in English is Casson (1994) . Casson gathers the ancient evidence to describe the activities and aims of ancient travellers, and his work offers a useful introduction to the subject. André and Baslez (1993) cover similar ground, but in addition to gathering and digesting the sources their work also reflects more recent developments in the study of ancient travel, and they offer more discussion of the cultural and intellectual context of their material. Two collections of articles on travel and travel writing, namely Camassa and Fasce (1991) and Adams and Roy (2007) , provide a good insight into a variety of lines of enquiry that have influenced the study of ancient travel in recent years.

Ancient travel writing has mainly been covered in works about specific authors. Recently the study of Pausanias in particular has led to further investigations of travel and travel writing. Pretzler (2007 a ) offers a general discussion of ancient travel, travel literature, and attitudes to geography and landscapes. Hutton (2005) analyses methods of travel writing, with a particular emphasis on the geographical structure of texts that deal with landscapes. Alcock, Cherry, and Elsner (2001) presents a wide range of approaches, including a number of papers discussing the reception of Pausanias.

Travel to distant places and the role the edges of the known world played in the imagination has been at the centre of stimulating discussion in recent years. Carpenter (1966) provides a basic overview of ancient explorers and their discoveries on the margins of the oikoumenē . Ideas about distant regions are discussed in Romm (1992) , and Hartog (1988 and 2001 ) contributes many valuable insights. Pilgrimage is another special aspect of travelling that has recently attracted a good deal of scholarly attention: much progress has been made in the analysis of pilgrimage in an ancient pagan as well as an early Christian context. Elsner and Rutherford (2005) is a collection of conference papers which offer a good overview of recent debates.

A dams , C. and R oy , J. eds. 2007 . Travel, Geography and Culture in Ancient Greece, Egypt and the Near East . London.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

A lcock , S. E., C herry , J. F., and Elsner, J. eds. 2001 . Pausanias: Travel and Memory in Roman Greece . Oxford.

A nderson , G. 1993 . The Second Sophistic: A Cultural Phenomenon in the Roman Empire . London.

A ndré , J.-M. and Baslez, M.-F. 1993 . Voyager dans l'antiquité . Paris.

A renz , A. 2006 . Herakleides Kritikos ‘Über die Städte in Hellas’. Eine Periegese Griechenlands am Vorabend des Chremonideischen Krieges . Munich.

B artsch , S. 1989 . Decoding the Ancient Novel: The Reader and the Role of Description in Heliodorus and Achilles Tatius . Princeton.

B ehr , C. A. 1968 . Aelius Aristides and the Sacred Tales . Amsterdam.

B ischoff , E. 1937 . ‘ Perieget. ’ In RE xix. 725–42.

C amassa , G. and F asce , S. eds. 1991 . Idea e realtà del viaggo: il viaggo nel mondo antico . Genoa.

C ampbell , M. B. 2002 . ‘Travel Writing and its Theory.’ In The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing . 261–78. P. Hulme and T. Youngs eds. Cambridge.

C arpenter , R. 1966 . Beyond the Pillars of Heracles: The Classical World Seen Through the Eyes of its Discoverers . New York.

C asson , L. 1994 . Travel in the Ancient World . 2nd edn. Baltimore, Md.

C awkwell , G. 2004 . ‘When, How and Why did Xenophon Write the Anabasis ?’ In The Long March: Xenophon and the Ten Thousand . 47–67. R. Lane Fox ed. NewHaven.

C larke , K. J. 1999 . Between Geography and History: Hellenistic Constructions of the Roman World . Oxford.

C ohen , E. 1992 . ‘ Pilgrimage and Tourism. Convergence and Divergence. ’ In Morinis (1992), 47–61.

D illon , M. 1997 . Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in Ancient Greece . London.

E lsner , J. 1997 . ‘Pilgrimage, Religion and Visual Culture in the Roman East.’ In The Early Roman Empire in the East . 178–99. S. E. Alcock ed. Oxford.

— 2001 . ‘Structuring “Greece”: Pausanias' Periegesis as a Literary Construct.’ In Alcock, Cherry and Elsner (2001), 3–20.

—and Rutherford, I. eds. 2005 . Pilgrimage in Graeco-Roman and Early Christian Antiquity: Seeing the Gods . Oxford.

G iesinger , F. 1937. ‘Periplous (2).’ In RE xix. 841–50. Habicht, C. 1985 . Pausanias' Guide to Ancient Greece . Berkeley.

H arrison , T. 2007 . ‘The Place of Geography in Herodotus' Histories .’ In Adams and Roy (2007), 44–65.

H artog , F. 1988 . The Mirror of Herodotus: The Representation of the Other in the Writing of History . Trans. J. Lloyd. Berkeley. (Originally published as Le Miroir dd'Hérodote: essai sur la représentation de l'autre . Paris, 1980.)

— 2001 . Memories of Odysseus: Frontier Tales from Ancient Greece . Trans. J. Lloyd. Edinburgh. (Originally published as Mémoire d'Ulysse: récits sur la frontière en Grèce ancienne . Paris, 1996.)

H olum , K. 1990 . ‘Hadrian and St. Helena. Imperial Travel and the Origins of Christian Holy Land Pilgrimage.’ In The Blessings of Pilgrimage . 61–81. R. G. Ousterhout ed. Urbana, Ill.

Horden, P. and Purcell, N. 2000 . The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History . Oxford.

H unt , E. D. 1982 . Holy Land Pilgrimage in the Later Roman Empire, AD 312–460 . Oxford.

— 1984 . ‘ Travel, Tourism and Piety in the Roman Empire: A Context for the Beginnings of Christian Pilgrimage. ’ Échos du Monde Classique , 3: 391–417.

H utton , W. E. 2005 . Describing Greece: Landscape and Literature in the ‘Periegesis’ of Pausanias . Cambridge.

J acob , C. 1991 . Géographie et ethnographie en Grèce ancienne . Paris.

J anni , P. 1984 . La mappa e il periplo. Cartografia antica e spazio odologico . Rome.

Jones, C. P. 2001 . ‘ Pausanias and his Guides. ’ In Alcock, Cherry, and Elsner (2001), 33–9.

L anzillotta , E. 1988 . ‘Geografia e storia da Ecateo a Tucidide.’ In Geografia e storiografia nel mondo classico . 19–31. M. Sordi ed. Milan.

L ightfoot , J. L. 2003 . Lucian: ‘On the Syrian Goddess’ . Edited with introduction, translation, and commentary. Oxford.

M illar , F. 1981 . ‘The World of The Golden Ass .’ JRS 71: 63–75.

M organ , J. R. 2007 . ‘ Travel in the Greek Novel. Function and Interpretation. ’ In Adams and Roy (2007), 139–60.

M orinis , E. A. ed. 1992 . Sacred Journeys: The Anthropology of Pilgrimage . London.

Ní Mheallaigh, K. 2008 . ‘ Pseudo-Documentarism and the Limits of Ancient Fiction. ’ AJP , 129: 403–31.

N enci , G. 1953 . ‘Il motivo dell' autopsia nella storiografia greca.’ Studi classici e orientali 3: 14–46.

P earson , L. I. C. 1960 . The Lost Histories of Alexander the Great . New York.

P fister , F. 1951 . Die Reisebilder des Herakleides. Einleitung, Text, Übersetzung und Kommentar mit einer Übersicht über die Geschichte der griechischen Volkskunde . Vienna.

Pikoulas, Y. A. 2007 . ‘ Travelling by Land in Ancient Greece. ’ In Adams and Roy (2007), 78–87.

P retzler , M. 2007 a . Pausanias: Travel Writing in Ancient Greece . London.

— 2007 b . ‘Pausanias' Intellectual Background: The Travelling pepaideumenos .’ In Adams and Roy (2007), 123–38.

P ritchett , W. K. 1980 . Studies in Ancient Greek Topography , Part 3: Roads . Berkeley.

P rontera , F. 1993 . ‘Sull'esegesi ellenistica della geografia omerica.’ In Philanthropia kai Eusebeia. Festschrift für Albrecht Dihle zum 70. Geburtstag . 387–97. G. W. Most, H. Peters-mann, and A. M. Ritter eds. Göttingen.

P urcell , N. 1996 . ‘ Travel. ’ OCD 1547–8.

R ohde , E. 1960 . Der griechische Roman und seine Vorläufer . 4th edn. Hildesheim.

R omm , J. S. 1992 . The Edges of the Earth in Ancient Thought: Geography, Exploration, and Fiction . Princeton.

Roy, J. 2007 . ‘Xenophon's Anabasis as a Traveller's Memoir.’ In Adams and Roy (2007), 66–77.

S chlam , C. C. 1992 . The Metamorphoses of Apuleius: On Making an Ass of Oneself . London.

S cullion , S. 2005 . ‘ “Pilgrimage” and Greek Religion: Sacred and Secular in the Pagan Polis .’ In Elsner and Rutherford (2005), 111–30.

S eel , O. 1961 . Antike Entdeckerfahrten. Zwei Reiseberichte . Zurich.

S nodgrass , A. M. ( 1987 ). An Archaeology of Greece: The Present State and Future Scope of a Discipline . Berkeley and London.

— 2001 . ‘ Pausanias and the Chest of Kypselos. ’ In Alcock, Cherry, and Elsner (2001), 127–41.

Stadter, P. A. 1980 . Arrian of Nicomedia . Chapel Hill, NC.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Wandering Poets in Ancient Greek Culture: Travel, Locality and Pan-Hellenism

Roosevelt rocha , federal university of paraná, brazil. [email protected].

Table of Contents

In Ancient times, it was very common that poets and performers were great travellers. This is a theme still overlooked, according to Richard Hunter and Ian Rutherford, the editors of the book under review here. It is a collection of papers formerly presented in April 2005, in a colloquium at the University of Cambridge in which the main questions were why poets travelled and how the skills of these outsiders were used by the local communities for their own purposes. In the Introduction, Hunter and Rutherford present the volume, asserting that “travel and wandering are persistent elements in both the reality and imaginaire of Greek poetry, and intellectual and cultural life more generally, from the earliest days” (p. 1). Orpheus was the first wandering poet and even a professional of the word like Empedocles of Acragas is a good example of the truth of this statement. But not only the poet could be a traveller. The public also could make a journey by attending or reading a text. And even more, a poem could travel and spread the fame of both poet and patron. Names like Theognis and Pindar are examples of that. And there’s still another possibility of travel in the act of composing or enacting a poem. This also can be seen as a kind of journey and the Argonautica , by Apollonius Rhodius, must be cited in this context.

It was very common that poets and performers travelled to receive honors like the proxenia but also to get payment, like the epinician composers and the Artists of Dionysus. This kind of activity continued into Hellenistic times and even into the Roman period, as the example of Archias, the poet defended by Cicero, shows. So, there were a munber of motivations that led to poetic mobility. Another one was the desire to receive commissions for celebrating the antiquities ( patria ), buildings and local worthies of particular towns. Thus the most common forms of performance were the encomia of the host city and its traditions.

Travels could lead to different kinds of innovations producing an ‘internationalization’ in the Archaic period. We have many notices of poets working far away from their homeland in those times, like Thaletas of Cretan Gortyna and Alcman (from Sparta or Lydian Sardis?). It could be important for a powerful ruler to draw in skilled poets: Polycrates of Samos attracted Ibycus from Rhegium and Anacreon from Teos; Periander of Corinth brought to his court Arion, from Lesbian Methymna; Peisistratus took Homer’s poetry to Athens and latter Anacreon and Simonides of Ceos spent some time there, before going to courts in Thessaly (the Tean) and in Sicily (the Cean). So, in Ancient times, a poet would take all the chances he had at hand to profit from his art (cf. Theocritus 16.34-47, cited p. 28).

But this phenomenon was not particular to Greece alone. As the editors say (p. 14), “singers and poets travel in many societies, perhaps most”. In Japan, in late medieval Europe, in medieval India, in Western Africa singers travelled to where they could find employment, and the best singers migrated to where they would be paid most. And to consider this comparative evidence can be useful in helping us to understand the ways poetic itinerancy developed in Ancient Greece.

Concluding their Introduction, the editors say (p.17) that poets travel to perform, but this does not exhaust the issue. It’s very import also to say that poets, local and foreign, played a role in celebrating local traditions. “One of the main functions of the shared cultural tradition was to provide an ideological fabric connecting the different Greek cities” (p. 20). So poets, when wandering, were reinforcing local traditions but also making Hellenic identity.

In the second chapter, ‘Hittite and Greek perspectives on travelling poets, texts and festivals’, Mary R. Bacharova starts by asserting that the mechanism by which literature from the Near East reached Greece has not been well studied. She argues that there was contact at an early stage between Pre-Greek and Anatolian poetic traditions. According to her, transmission of cultural practices via Anatolia during the Mycenean period should be given serious consideration. She examines the mechanisms by which second-millenium Anatolian singers and other ‘masters of the word’ made their way from one location to another. The focus is particularly on two related settings: the worship of an imported god and festivals. In analysing the texts, she presents phraseological correspondences that she claims to be “good indirect evidence of the contact between wordsmiths through whom the phrasing crossed langages” (p. 29). In conclusion, Bacharova asserts that festivals from Anatolia and other parts of the Near East shared much in common with Greek festivals of the first millenium.

Peter Wilson is the author of chapter 3, “Thamyris the Tracian: the archetypal wandering poet?”. The author notes that Thamyris may seem, at first glance, the perfect ‘wandering’ archetypal poet, but, in fact, he is a difficult role-model. He is a marginal figure in Greek myth and literature, even though an ancient and persistent presence. He comes from the margins of the Hellenic world. As Wilson argues, Thamyris is a useful model of opposition, a figurehead for a religious tradition that ran against Olympian religion and Homeric epic itself. Perhaps the most interesting contribution of this paper is the analysis made by Wilson of a number of Sophoclean fragments, specially those from the play Thamyras or Mousai . Thamyris was a kind of revolutionary poet who opposed the poetic status quo represented by the Homeric Muses. For this reason, his identification with the poets of the New Music of the second half of the fifth century was a natural development, as Wilson masterfully shows.

“Read on arrival” is the title of chapter 4, by Richard P. Martin. In this paper the author tries to make a diachronic examination of the strategies adopted by wandering poets and performers in order to delineate a typology. In doing that, he wants to explore the poetics of a number of genres related or not to the travelling poets. The strategies of the wandering poets are different from those of the metanastic figures (a term proposed by Martin in 1992) 1 because these had a kind of one-way ticket, while the travelling poets had “the equivalent of a long-term Eurail pass” (p. 81). Based on this, Martin analyses Aristophanes’ Birds 904-57, where a parody is presented of a travelling poet’s arrival that can be viewed as representing the typical behavour of a poet seeking for a patron; Pindar’s Pythian 4, 275-280; Odyssey 17.382-6; Bacchylides’ 5.7-14 and 3.90-8; the Hymn to Apollo 166-75 and some other texts are used to establish the six gambits that form the handbook of strategies and rules for the wandering poet: 1. praise the place and let the people come later; 2. make yourself the voice of tradition; 3. for success, don’t dress; 4. inflate your worth; 5. handle many genres ( polueideia ); and pratice, pratice, pratice. In conclusion, Martin says that “the successful roaming poet will be one who makes the memorized look spontaneous” (p. 103). In this context, the concept of re-performance is very important, because, as Martin argues (p. 103), there must have been a kind of temporary textualization of a repertoire that was ‘read’ in a type of composition-in-performance characteristic of oral tradition.

Ewen Bowie, in chapter 5, entitled “Wandering poets, archaic style”, studies archaic wandering poets’ representation in their poetry of themselves and of their performances. He is interested mainly in monodic lyric poetry down to 500 BC. According to Bowie, travelling poets can be divided in three categories: 1. the poet as a member of a group (Archilochus, Tyrtaeus, Mimnermus and maybe Anacreon; 2. Solitary travellers outside their polis who performed in a symposium and did not travel in order to sing (Semonides, Alcaeus and Solon); 3. Professional poets or ones who travelled in order to sing and to participate in symposia as guests (Ibycus [maybe] and Anacreon [maybe] and Simonides).

In Chapter 6, “Defining local identities in Greek lyric poetry”, Giovan Battista D’Alessio argues that in the formative period of the Greek poleis the construction of a local identity was often voiced by foreign poets. He explores some case studies of public poetic discourse as a means for defining and promoting civic identities in the archaic and classical periods, and of the different strategies by which such a poetic communal self-definition was constructed. D’Alessio studies the cases of Eumelus’ Delian Prosodion for the Messenians, refered to by Pausanias (4.4.1 and 4.33.2; see also PMG 696), and also the Delian Prosodia by Pronomus (for Chalcis; see Paus. 9.12.6) and Amphicles of Rheneia (for the Athenians; see ID 1497). Further on, the author dedicates some pages also to the Nephelokokkygia episode, in Aristophanes Birds (851-8; 863-904; 1318-22) and to the ‘choral’ elegy by Tyrtaeus (the poetic voice as a collective discourse) to understand the relevance and impact of lyric discourse as an important medium for expressing a communal image of the polis. The last case study analysed by D’Alessio is Pindar’s Paeans 2 and 4. In conclusion, the author says that “public poetic performance (…) was one of the privileged media for Greek cities to give voice to their ‘identities’ from the archaic age onward” (p. 166).

“Wandering poetry, ‘travelling’ music: Timotheus’ muse and some case-studies of shifting cultural identities” is the title of chapter 7, by Lucia Prauscello. The author investigates the ways the poetry of Timotheus of Miletus was exploited and re-interpreted in different moments and in different places of Ancient Greece. She says she is concerned with whether and to what extent re-performances and musical re-settings may have affected the generic definition of the text itself and its reception among the audience. In this context it is important to note that musical performance is a prominent feature in the rhetoric of self-construction of Greek cultural identities, in the poleis but also in broader geographical limits. Prauscello examines how the poetry of Timotheus was re-used and interpreted in Sparta (analysing the ‘forged’ Laconian decree transmitted by Boethius [ De inst. mus. 1.1]); in Arcadia (commenting on passages from Polybius [4.19-21], Plutarch [ Philop. 11] and Pausanias [8.50.3]; and in Crete (taking as points of departure the inscriptions ICret V.viii.11 [Knossos] and xxiv.1 [Priansos]). In conclusion, we could say that the interpretation and value of a text varies with time and withplace . A poem by Timotheus could be seen positively by the Arcadians, but could also be banished by the Spartans for different motives.

Andrej Petrovic is the author of chapter 8, entitled “Epigrammatic contests, poeti vaganti and local history”. He discusses the role of wandering poets as local historians. The focus is on texts dated up to the end of Hellenistic times written by wandering poets for public monuments. Petrovic is concerned with the fact that the composition of public epigrams in a number of cases was a task fulfilled by wandering poets. He is also interested on the procedure through which texts for public monuments were chosen and his response to this question is that the texts were chosen after contests that took place in public festivals and in the framework of public commissions. Petrovic argues also that these public epigrams had a supra-local reception, even though they were composed for local addressees. He sugests in the end that these poems were diffused through epigrammatic collections organized on the principle of interest in local history.

Chapter 9 is by Sophia Aneziri, who writes about “World travellers: the associations of Artists of Dionysus”. According to her, poets and musicians, in any time and in any society, have their mobility determined by three factors: first, by the features of the society they are operating in, along with conditions of travel and communication; second, the existence of opportunities for performance that might attract performers, such as festivals and competitions; and third, she asserts that it is important to know if the poets work by themselves or are organized in professional groups and if they stay at home or are continuously travelling. In her paper, she explores these three factors in relation to the Artists of Dionysus operating in the Mediterranean world during the Hellenistic and imperial periods. The volume of travel was very great in these periods because of the explosion in festival culture, but the pattern of movement of the Artists was very different in the two periods. In Hellenistic times artists of many places organized themselves in regional associations, but in the imperial period these regional associations lose their importance and the Association of the Artists of Dionysus achieves the status of an empire-wide network.

Ian Rutherford is the author of chapter 10, “Aristodama and the Aetolians: an itinerant poetess and her agenda”. Born most likely in the third quarter of the third century BCE in Smyrna, the poetess Aristodama is known to us only because around 220 BCE she travelled to central Greece and was honored by two cities due to the skill she demonstrated when presenting her poems there. Rutherford analyses two decrees, one of the city of Lamia (218/217 BCE, IG IX 2, 62 = Guarducci 17), the other from the Lokrian city of Khalaion ( FD 3.2.145 = G17*). He also compares the case of Aristodama with those of other poetesses and performers and examines what the relationship between Aristodama and those cities might be. Rutherford defends the hypothesis that the Aetolians engaged Aristodama to write about Aetolia and to create a sort of pan-Aetolian poetic tradition, forging in this way a political community through song. This is another example of how poetry can work as a mechanism that creates a political and cultural identity.

In the last chapter, “Travelling memories in the Hellenistic world”, Angelos Chaniotis starts his paper by analysing a document in which is narrated the visit of three citizens of the city of Kytenion in Doris to the city of Xanthos. The visitors wanted financial aid to help reconstruct the walls of their city and, in order to get that, they used many strategies to show that there was a kinship between Kytenion and Xanthos. Chaniotis is concerned with the impact cultural mobility had on the shaping of memory in the Hellenistic world. He is more interested in the contribution of orators, historians and envoys than in that of poets.

In conclusion, I want to say that this is a wonderful book. It deals with a matter whose importance is still underestimated. The authors of the different papers enter into a dialogue with each other and write in a way that is certain to inspire new research. The texts are very well edited and I have found only a few insignificant typos. All in all, this is an amazing collection.

1 .Martin, R. ‘Hesiod’s Metanastic Poetics’, Ramus 21: 11-33.

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

10 Badass Travelers Throughout History

These trailblazers staged epic journeys across new lands, broke cultural barriers, and revealed the radical diversity of the world around us.

- Nat Geo Expeditions

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- TRAVEL AND ADVENTURE

- HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

- ANCIENT HISTORY

- MODERN HISTORY

- PEOPLE AND CULTURE

You May Also Like

How to plan a family city break in Rome

6 reasons to visit Khiva, the tourist capital of the Islamic world for 2024

How to plan a weekend in Murcia, one of Spain's most underrated regions

A guide to Jaipur's craft scene, from Rajasthani block printing to marble carving

How to plan a weekend in South Moravia, Czech wine country

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Tourism Through the Ages: The Human Desire to Explore

- Read Later

Although taking a summer vacation is now a standard aspect of modern-day civilization for many, it wasn’t always that way. Tourism was far less common in ancient times than it is today, but that certainly doesn’t mean it didn’t occur at all. Even in ancient times, people had a natural curiosity about the world around them and yearned to explore.

However, tourism didn’t necessarily look the same then as it does now. So what did tourism look like, and where did ancient peoples like to travel the most? What was the perception of tourists in ancient times versus today?

What was Ancient Tourism Like?

Tourism as we think of it has not always existed. In fact, travel was not possible for most people in ancient times. Travel was often difficult and full of dangers such as disease , starvation, dehydration, or death by wild animals. Because of this, travel was often seen as too risky unless absolutely necessary, such as for relocation, or religious, political, or medical purposes.

However, travel did still happen. Armies would travel to take over new lands or conquer new cities. Tradesmen would travel to popular trade spots throughout their countries to sell goods for profits, while others would travel there to buy utilitarian or luxury items for their homes. Others would travel for important religious ceremonies that they were required to attend. Travel of this nature was considered a need within society, rather than a want, so not tourism as such.

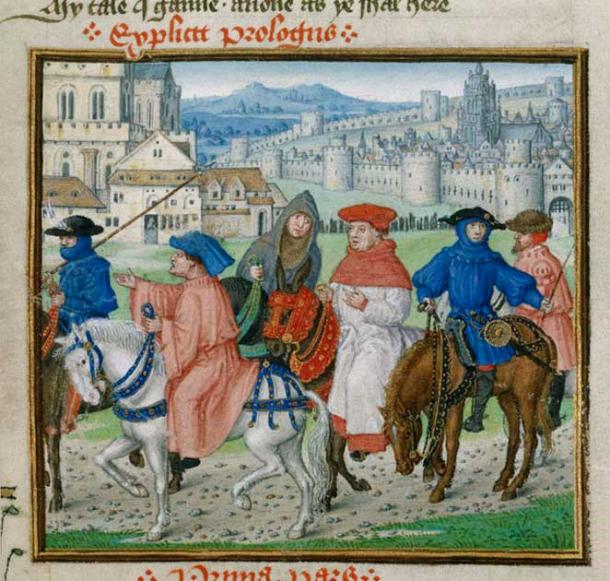

Lydgate and Pilgrims to Canterbury. Early ‘tourism’ was frequently for religious ceremonies and pilgrimages. (Jim Forest / CC BY NC ND 2.0 )

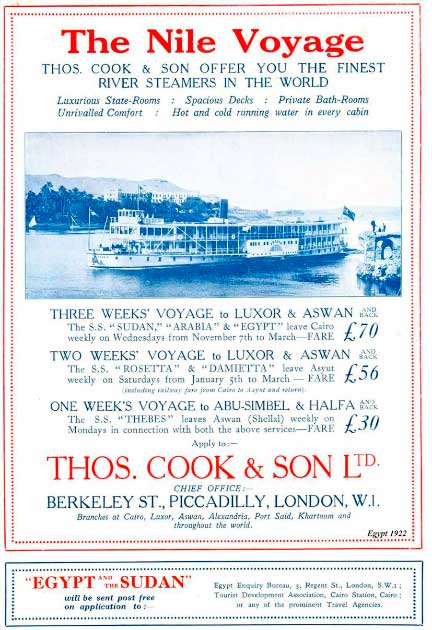

As time went on, technology advanced. With the expansion of roads and the development of more efficient travel using boats , chariots , and carriages, travel for leisure, or tourism, became an intriguing possibility. However, many individuals struggled with the same tourism questions we do today: if they could even afford to travel, and if they could, where they would go.

Early tourists tended to avoid cities with political or civil unrest as it could be dangerous in the event of an uprising. It’s unsurprising these would be eliminated as tourism destinations . They would also avoid cities their own regions had hostility towards, as that was also considered risky business. They would instead choose regions that were not known to be dangerous, just to see what was out there.