Tourism Multiplier

Concept of Tourism Multiplier : Tourism being a multi-faceted and interdisciplinary industry has a great potential in generating income and employment (direct and indirect). Tourism , being one of the largest industries for many countries, has a high multiplier effect. The inflow of money from Tourist Generating Region to Tourist Destination Region through various sectors of the economy is very high which contributes to the economic development.

Tourism is on higher trajectory of creation as it not only creates jobs in its own tertiary sector, it also reassures growth in the related primary and secondary sectors of industry. This phenomenon is known as the multiplier effect. In other words, how many times a money spent by a tourist circulates in a particular country’s economy.

You may read Tourism Product Concept

Money spent in a hotel or restaurant helps to create jobs directly in the hotel premises. It also generates jobs indirectly in related or allied industry elsewhere in the economy. For example, the hotel buys food from local farmers or market supplier, who may spend some amount of this money on clothes or other products. Tourists often buy souvenirs from destination this increases demand for local products, which upsurges secondary employment in locally.

Also read about Hospitality

The multiplier effects continue or have ripple effect until the money in due course ‘leaks’ from the economy through imports or other methods.

Multiplier concept is based on Keynesian analysis. It tracks the money spent by the tourists as it filters through the economy. The revenue decreases in a geometric progression at each round as a result of leakages.

Direct tourism expenditures occur when different suppliers of tourism services such as travel agencies, hotels, restaurants etc. provide services. Similarly, indirect expenditures occur due to purchase of handicrafts and availing services during the entire tourism experiences. Again, these expenditures on tourism lead to providing wages and companies can make profit out of tourism business and government may generate revenue through taxes. Causing a wide spread impact on the economy in terms of income, employment and further new investment, this figure also shows how leakages may occur due to high imports causing multiplier weak.

You may read Tourism Product Concept

Tourism Expenditure and Multiplier

Tourism Expenditure can be broadly divided into three types. Namely

- Direct Expenditure,

- Indirect Expenditure

- Induced Expenditure

- Direct Tourism Expenditure consists of expenditures by the tourists on goods and services on hotels, shops, and other tourism related services. It is otherwise known as tourist’s initial spending which creates direct revenue.

- Indirect Tourism Expenditure includes the transaction between businesses caused by direct tourism expenditures. It is otherwise known as the initial process of re-spending i.e., employees’ salary. For example, purchase made by hotels from local suppliers and goods bought by suppliers from the wholesalers.

- Induced Tourism Expenditure consists of increase consumption resulting from increase in income provided by direct tourism expenditure. It is otherwise known as the secondary process For example, the employees of the hotel purchase goods and services otherwise known as re-spending.

Types of Multiplier

According to Lickorish and Jenkins, tourist multipliers can be classified into five main broad categories:

- Sales or transaction multiplier : The sales or transaction multiplier measures direct, indirect and induced turnover generated by extra unit of tourism expenditures or additional business turnover.

- Output or production multiplier: The output or production multiplier measures the extra production and accounts an increase in stock levels at hotels, restaurants and shops as a result of increase in commercial or trading activities. The output multipliers are mainly concerned with actual levels or changes in production or output rather than the volume of sales or value.

Read more on Tourism Product Life Cycle

- Income multiplier: An income multiplier measures the income (receipt) generated by an additional unit of tourist expenditure. The salaries remunerated to overseas residents are not counted, only the proportion of these that has been spent in the area should be included while measuring Income multiplier.

- Employment multipliers: Employment multipliers measure the effects of extra economic activities on employment i.e., the increased number of primary and secondary jobs generated by an extra unit of tourism expenditure. This multiplier can be expressed in namely direct and indirect employment.

- The official or government revenue tourism multiplier: It indicates the net value ie, taxes less subsidies, of government income from tourism .

Use of Multiplier

Multiplier is a tool used to analyze the economic effect of increase in tourism expenditure and its influence on other sectors of the economy. The value of multiplier depends on the particular features of the tourism in the area studied and the characteristics of the local economy.

The greater the range of activities in the areas the greater would be the chance of higher number of exchange between them. Therefore, the greater is the size of multiplier then the export would be more than import. However, a higher number of imports can reduce the value of multiplier.

Factors Affecting the Size of Tourism Multiplier

The size of the multiplier is affected by different factors. These include:

- The initial volume of tourism expenditure,

- Supply constraints in the area of the economy,

- The size of the area economy,

- Value added in the first round expenditure,

- Tourism industry linkages with the area of economy, and

The size of the multipliers depends on four basic factors:

- Size and economic diversity. The overall size of region or country and economic diversity of its economy have a significant role in determining multipliers. Regions with large and diversified economies and producing goods and services of higher order will have high multipliers. As the households and business firms will consume most of the goods and services produced locally.

- Geographic Extent and its Role: It denotes the geographic extent of a region or country and its role within the broader region. Regions of a large geographic extent will have higher multipliers than small areas other things remaining constant, as transportation costs will tend to constrain imports. Regions or countries that serve as central location for the surrounding area or regions will have higher multipliers than those isolated areas.

- Nature of the Economic Sectors: The nature and characteristics of the economic sectors under consideration also have substantial impacts. Multipliers vary across all sectors of the economy as the mix of labor and other inputs of every sector have their own propensity to buy goods and services available within the region. As Tourism and allied businesses are labor intensive, it tends to have greater induced rather than indirect effects on sector. When a single multiplier describes a region, mostly it represents an aggregate or average value across many sectors. For more precise and accurate estimates sector-specific multipliers are to be used if possible. A sector-specific multiplier will precisely estimate the secondary effects within a given sector on sales of services and product.

- Year: A multiplier represents the nature of the economy at a given point in time. As any changes over time in response in the economic structure or price changes may change multipliers for a given region. While using regional economic models or multipliers any changes in spending are generally price adjusted to the model year for region. Sales or income multipliers are more directive to general price inflation than employment multipliers and ratios have more chances to change over time.

Limitations of Tourism Multiplier

Insufficient Data : It is observed that due to insufficient data regarding the tourism activities, it is not accurate enough to be used in tourism planning.

Variation in MPC: Variation in marginal propensity to consume leads to measurement in accurate effects on inflation.

Inelasticity of Supply: It is assumed that supply is elastic in all sectors of production. However, developing countries are confronted with a number of problems including

- Lack of availability of resources

- Shortage of foreign currencies

- Inefficiency and insufficient productivity.

The Static Feature of Production Function: Multiplier concept can only explain about the past but not forecast the future.

The Time Factor: The study of multiplier does not consider the length of time necessary for the multiplier effect to influence the economy.

Also read Cost-Benefit Analysis

You Might Also Like

Tourist Circuits of India Part-I

Forms of Business Ownerships

Global Indicators

- Tectonics Fieldwork

- Urban Fieldwork

- Ecology Fieldwork

- Coastal Fieldwork

- River Fieldwork

- Compass Reading

- Accommodation

- Geography Forum

- Google Compass

- Google Earth Teaching

- Google Street Maps

- OpenStreetMap Compass

- OS Maps Compass

- Coursework Helpline

- Urban Case Study

- Climate Vocabulary

- Coasts Vocabulary

- Causes and Effects

- Glaciation Vocabulary

- Rivers Vocabulary

- Anticyclones

- Frontal Rain

- Relief Rain

- Employment Structure

- Agribusiness

- Costa del Polythene

- LEDC Rice Farming

- Location Change

- Multiplier Effect

- Formal/Informal

- Transnational

- Distribution

- Tropical Rainforest

- Demographic Transition

- Population Change

- Ethnic Characteristics

- LEDC/MEDC Structure

- Population Dependency

- Rural/Urban Structure

- LEDC Land Use

- MEDC Land Use

- Site and Situation

- Urban Zones

- Zomba Case Study

- Classification

- Attractions

- Costs and Benefits

- Urban Sprawl

- Introduction

- Data Collection

- Data Presentation

- Organisation

- Economic Activity

- Economic Change

- Grid References

- LEDC Urban Land Use

- Map Bearings

- Map Reading

- Population Structure

- Rainforest Management

- Rainforest Vegetation

- Weather at a Front

- Active Test Users

- Change Name

- Your Data Log

- Classroom Support

- Coursework Examples

- Password Protection

- Geo Factsheets

- Data presentation

- Methodology

- Capital Cities

- Describing Places

- Open or Free Text

- Test Troubleshooting

- Using a Compass

Tourism Multiplier Effect

Tourism not only creates jobs in the tertiary sector, it also encourages growth in the primary and secondary sectors of industry. This is known as the multiplier effect which in its simplest form is how many times money spent by a tourist circulates through a country's economy.

Money spent in a hotel helps to create jobs directly in the hotel, but it also creates jobs indirectly elsewhere in the economy. The hotel, for example, has to buy food from local farmers, who may spend some of this money on fertiliser or clothes. The demand for local products increases as tourists often buy souvenirs, which increases secondary employment.

The multiplier effect continues until the money eventually 'leaks' from the economy through imports - the purchase of goods from other countries.

Encyclopedia of Tourism pp 1–2 Cite as

Multiplier effect, tourism

- Emily Ma 3

- Living reference work entry

- Later version available View entry history

- First Online: 01 January 2015

119 Accesses

2 Citations

An important component of research is to estimate the economic impacts of tourism. Input–output (I-O) models have been widely used to estimate tourism’s contributions to an economy (Crompton et al. 2001 ; Lee and Taylor 2005 ). The intent is to estimate the increase in an economy by directly calculating the increase in output and also by considering the growth in related industries, such as suppliers of other goods and services (Kim et al. 2003 ). A key concept in understanding I-O models is the multiplier effect.

A multiplier in economics is a ratio that measures how much a dependent variable changes in response to a change in the independent variable. Tourism multiplier effect, in simple terms, refers to how many times money spent by a tourist can circulate in a country’s economy. Tourism can directly contribute to the development of the economy by bringing in income and generating new employment opportunities (Khan et al. 1990 ). More importantly, it can contribute to economy through...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Crompton, J., S. Lee and T. Shuster 2001 A Guide for Undertaking Economic Impact Studies: The Springfest Example. Journal of Travel Research 40:79-87.

Article Google Scholar

Khan, H., C. Seng, and W. Cheong 1990 Tourism Multiplier Effects on Singapore. Annals of Tourism Research 17:408-418.

Kim, S., K. Chon, and K. Chung 2003 Convention Industry in South Korea: An Economic Impact Analysis. Tourism Management 24:533-541.

Lee, C., and T. Taylor 2005 Critical Reflections on the Economic Impact Assessment of a Mega-event: The Case of 2002 FIFA World Cup. Tourism Management 26:595-603.

Vanhove, N. 2005 The Economics of Tourism Destinations. Burlington: Elsevier.

Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Griffith Business School, Griffith University, 170 Kessels Road, QLD 4111, Brisbae, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Emily Ma .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Hospitality Leadership, University of Wisconsin-Stout, Menomonie, Wisconsin, USA

Jafar Jafari

School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR

Honggen Xiao

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Ma, E. (2015). Multiplier effect, tourism. In: Jafari, J., Xiao, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Tourism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_454-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_454-1

Received : 21 April 2015

Accepted : 21 April 2015

Published : 22 September 2015

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-01669-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Business and Management Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Chapter history

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_454-2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_454-1

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What is the multiplier effect? Definition and examples

A Multiplier or the Multiplier Effect is the factor by which the return resulting from an expenditure is greater than the expenditure itself, or the way in which a change in spending leads to an even bigger change in income. The term is generally used in reference to how much a certain amount of expenditure increases total national income or GDP (gross domestic product).

Moreover, the multiplier effect is not uniform across different sectors; for instance, spending on infrastructure or technology may have a higher multiplier effect compared to other types of government expenditure

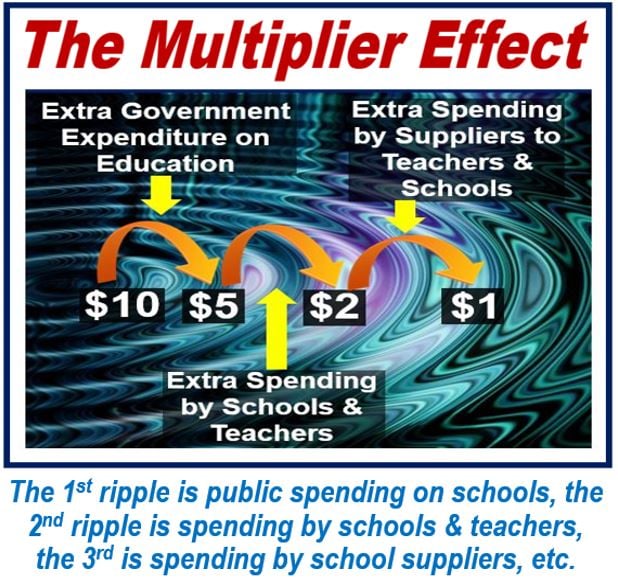

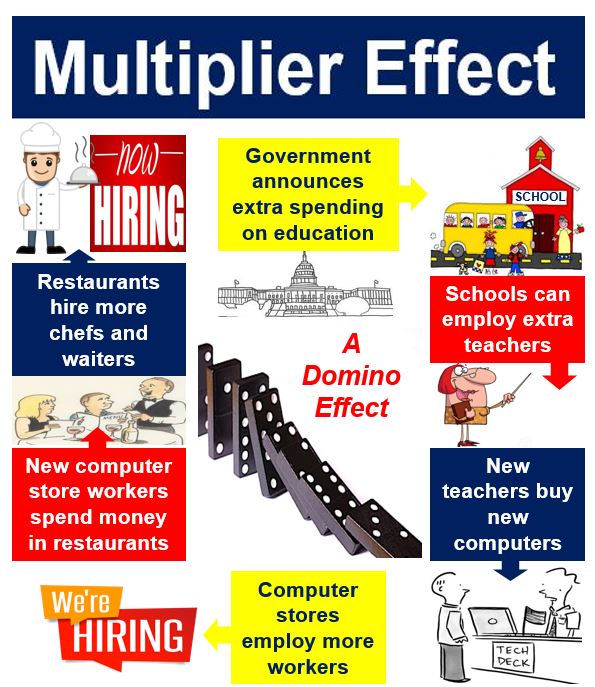

Example of the multiplier effect – education

Imagine that the government spends an extra $5 billion on education. The immediate effect is an increase in teachers’ income as well as greater sales of goods and services for companies that supply schools.

These people and businesses will in turn spend their extra income, making other entities richer, who spend some of that money, etc.

As far as the theory goes, this process should go on and on forever, in which case the multiplier has an infinite value. Most people and entities who become richer as a result of the initial expenditure put some of that money into savings rather than spending it.

How much of their extra income is spent depends on their marginal propensity to consume . The multiplier’s value can be calculated by using the following formula:

Muliplier = 1 ÷ (1 – marginal propensity to consume)

If the marginal propensity to consume are 0.25 or 0.50, the multipliers are 1.33 and 2 respectively.

When talking about the amount of money that a bank can generate for each dollar of reserves , we use the term ‘money multiplier’ . When discussing government spending, and how that initial extra expenditure can create additional wealth, we use the term ‘fiscal multiplier’ .

The multiplier and John Maynard Keynes

British economist John Maynard Keynes, whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and governments’ economic policies, created the multiplier theory and its equations.

Keynes said that an increase in government spending created a proportional boost to overall income or GDP, because the additional spending would have a ripple effect through the economy.

Keynes first mentioned this effect at the height of the Great Depression in 1933 in his book – The Means to Prosperity . While addressed mainly to the British Government, his work also contained suggestions for several other countries that were also affected by the Great Depression.

US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other world leaders received a copy. The British and US governments took the work seriously. This paved the way for the later general acceptance of Keynesian ideas.

According to Keynes, with a multiplier of two, the economy grows by $2 while the government deficit increases by $1.

Scores of papers written by economists have attempted to estimate fiscal multipliers since the global financial crisis of 2007/8 and the Great Recession that followed. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) calculated that the ‘harmful’ economic multiplier for fiscal contractions was often at least 1.5.

The Economist made the following comment regarding governments’ recent fiscal stimulus:

“Even as many policymakers remain committed to fiscal consolidation, plenty of economists now argue that insufficient fiscal stimulus has been among the biggest failures of the post-crisis era. Decades after its conception, Keynes’s multiplier is relevant, controversial and ascendent.”

Tourism and the multiplier effect

The multiplier effect from tourism is relatively high, due to several factors:

Diverse spending

Tourists spend money on food, drinks, tours, souvenirs, entertainment, taxis and other transportation, and general shopping. This diverse spending supports various businesses and sectors within the economy.

Tourism typically creates jobs both directly and indirectly. Waiters, chambermaids, and airport staff are examples of direct employment, while shop assistants, taxi drivers, and those working in food production and distribution are examples of indirect employment.

Stimulating local economies

In regions where tourists are major contributors to the overall economy, tourism can be particularly impactful. Florida, the South of France, and many parts of Spain became prosperous partly thanks to tourism.

Seasonal boost

In some parts of the world, the influx of tourists can provide a major economic boost during certain times of the year. In many cases, these boosts help sustain year-round operations, i.e., permanent jobs.

Promotion of Related Industries

Industries involved in the creation of infrastructure, such as construction companies benefit significantly from tourism.

Foreign Exchange Earnings

In Mexico, for example, tourism is an enormous earner of foreign exchange, especially US dollars. Foreign exchange earnings help maintain a positive balance of payments.

The extent of tourism’s multiplier effect may vary depending on what type of tourism a country or area receives (e.g., luxury vs. budget) and how much of the money that tourists spend remains locally versus going to foreign-owned entities.

Becoming over-reliant on tourism is risky, as the COVID-19 pandemic revealed. The economies of countries like Thailand, Spain, and the Maldives, which depend heavily on tourism, suffered significantly during the pandemic.

Video – What is the multiplier effect?

This interesting video presentation, from our YouTube partner channel – Marketing Business Network , explains what the ‘Multiplier Effect’ is using simple and easy-to-understand language and examples.

Share this:

- Renewable Energy

- Artificial Intelligence

- 3D Printing

- Financial Glossary

- Open access

- Published: 05 January 2021

The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis

- Haroon Rasool ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0083-4553 1 ,

- Shafat Maqbool 2 &

- Md. Tarique 1

Future Business Journal volume 7 , Article number: 1 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

120k Accesses

87 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Tourism has become the world’s third-largest export industry after fuels and chemicals, and ahead of food and automotive products. From last few years, there has been a great surge in international tourism, culminates to 7% share of World’s total exports in 2016. To this end, the study attempts to examine the relationship between inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth by using the panel data over the period 1995–2015 for five BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries. The results of panel ARDL cointegration test indicate that tourism, financial development and economic growth are cointegrated in the long run. Further, the Granger causality analysis demonstrates that the causality between inbound tourism and economic growth is bi-directional, thus validates the ‘feedback-hypothesis’ in BRICS countries. The study suggests that BRICS countries should promote favorable tourism policies to push up the economic growth and in turn economic growth will positively contribute to international tourism.

Introduction

World Tourism Day 2015 was celebrated around the theme ‘One Billion Tourists; One Billion Opportunities’ highlighting the transformative potential of one billion tourists. With more than one billion tourists traveling to an international destination every year, tourism has become a leading economic sector, contributing 9.8% of global GDP and represents 7% of the world’s total exports [ 59 ]. According to the World Tourism Organization, the year 2013 saw more than 1.087 billion Foreign Tourist Arrivals and US $1075 billion foreign tourism receipts. The contribution of travel and tourism to gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to reach 10.8% at the end of 2026 [ 61 ]. Representing more than just economic strength, these figures exemplify the vast potential of tourism, to address some of the world´s most pressing challenges, including socio-economic growth and inclusive development.

Developing countries are emerging as the important players, and increasingly aware of their economic potential. Once essentially excluded from the tourism industry, the developing world has now become its major growth area. These countries majorly rely on tourism for their foreign exchange reserves. For the world’s forty poorest countries, tourism is the second-most important source of foreign exchange after oil [ 37 ].

The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries have emerged as a potential bloc in the developing countries which caters the major tourists from developed countries. Tourism becomes major focus at BRICS Xiamen Summit 2017 held in China. These countries have robust growth rate, and are focal destinations for global tourists. During 1990 to 2014, these countries stride from 11% of the world’s GDP to almost 30% [ 17 ]. Among BRICS countries, China is ranked as an important destination followed by Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa [ 60 ].

The importance of inbound tourism has grown exponentially, because of its growing contribution to the economic growth in the long run. It enhances economic growth by augmenting the foreign exchange reserves [ 38 ], stimulating investments in new infrastructure, human capital and increases competition [ 9 ], promoting industrial development [ 34 ], creates jobs and hence to increase income [ 34 ], inbound tourism also generates positive externalities [ 1 , 14 ] and finally, as economy grows, one can argue that growth in GDP could lead to further increase in international tourism [ 11 ].

The tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) proposed by Balaguer and Cantavella-Jorda [ 3 ], states that expansion of international tourism activities exerts economic growth, hence offering a theoretical and empirical link between inbound tourism and economic growth. Theoretically, the TLGH was directly derived from the export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH) that postulates that economic growth can be generated not only by increasing the amount of labor and capital within the economy, but also by expanding exports.

The ‘new growth theory,’ developed by Balassa [ 4 ], suggests that export expansion can trigger economic growth, because it promotes specialization and raises factors productivity by increasing competition, creating positive externalities by advancing the dispersal of specialized information and abilities. Exports also enhance economic growth by increasing the level of investment. International tourism is considered as a non-standard type of export, as it indicates a source of receipts and consumption in situ. Given the difficulties in measuring tourism activity, the economic literature tends to focus on primary and manufactured product exports, hence neglecting this economic sector. Analogous to the ELGH, the TLGH analyses the possible temporal relationship between tourism and economic growth, both in the short and long run. The question is whether tourism activity leads to economic growth or, alternatively, economic expansion drives tourism growth, or indeed a bi-directional relationship exists between the two variables.

To further substantiate the nexus, the study will investigate the plausible linkages between economic growth and international tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. Financial markets are considered a key factor in producing strong economic growth, because they contribute to economic efficiency by diverting financial funds from unproductive to productive uses. The origin of this role of financial development may is traced back to the seminal work of Schumpeter [ 50 ]. In his study, Schumpeter points out that the banking system is the crucial factor for economic growth due to its role in the allocation of savings, the encouragement of innovation, and the funding of productive investments. Early works, such as Goldsmith [ 18 ], McKinnon [ 39 ] and Shaw [ 51 ] put forward considerable evidence that financial development enhances growth performance of countries. The importance of financial development in BRICS economies is reflected by the establishment of the ‘New Development Bank’ aimed at financing infrastructure and sustainable development projects in these and other developing countries. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no attempt has been made so far to investigate the long-run relationship Footnote 1 between tourism, financial development and economic growth in case of BRICS countries. Hence, the present study is an attempt to fill the gap in the existing literature.

Review of past studies

From last few decades there has been a surge in the research related to tourism-growth nexus. The importance of growth and development and its determinants has been studied extensively both in developed and developing countries. Extant literature has recognized tourism as an important determinant of economic growth. The importance of tourism has grown exponentially, courtesy to its manifold advantages in form of employment, foreign exchange production household income and government revenues through multiplier effects, improvements in the balance of payments and growth in the number of tourism-promoted government policies [ 21 , 41 , 53 ]. Empirical findings on tourism and economic development have produced mixed finding and sometimes conflicting results despite the common choice of time series techniques as a research methodology. On empirical grounds, four hypotheses have been explored to determine the link between tourism and economic growth [ 12 ]. The first two hypotheses present an account on the unidirectional causality between the two variables, either from tourism to economic growth (Tourism-led economic growth hypothesis-TLGH) or its reserve (economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis-EDTH). The other two hypotheses support the existence of bi-directional hypothesis, (bi-directional causality hypothesis-BC) or that there is no relationship at all (no causality hypothesis-NC), respectively. According to TLEG hypothesis, tourism creates an array of benefits which spillover though multiple routes to promote the economic growth [ 55 ]. In particular, it is believed that tourism (1) increases foreign exchange earnings, which in turn can be used to finance imports [ 38 ], (2) it encourages investment and drives local firms toward greater efficiency due to the increased competition [ 3 , 31 ], (3) it alleviates unemployment, since tourism activities are heavily based on human capital [ 10 ] and (4) it leads to positive economies of scale thus, decreasing production costs for local businesses [ 1 , 14 ]. Other recent studies which find evidence in favor of the TLGH hypothesis include [ 44 , 52 ]. Even though literature is dominated by TLGH, few studies produce a result in support of EDTH [ 40 , 41 , 45 ]. Payne and Mervar [ 45 ] posit that tourism growth of a country is mobilized by the stability of well-designed economic policies, governance structures and investments in both physical and human capital. This positive and vibrant environment creates a series of development activities which proliferate and flourish the tourism. Pertaining to the readily available information, bi-directional causality could also exist between tourism income and economic growth [ 34 , 49 ]. From a policy view, a reciprocal tourism–economic growth relationship implies that government agendas should cater for promoting both areas simultaneously. Finally, there are some studies that do not offer support to any of the aforementioned hypotheses, suggesting that the impact between tourism and economic growth is insignificant [ 25 , 47 , 57 ]. There is a vast literature examining the relationship between tourism and growth as a result, only a selective literature review will be presented here.

Banday and Ismail [ 5 ] used ARDL cointegration model to test the relationship between tourism revenue and economic growth in BRICS countries from the time period of (1995–2013). The study validates the tourism-led growth hypothesis for BRICS countries, which evinces that tourism has positive influence on economic growth.

Savaş et al. [ 54 ] evaluated the tourism-led growth hypothesis in the context of Turkey. The study employed gross domestic product, real exchange rate, real total expenditure and international tourism arrivals to sketch out the causality among variables. The result reveals a unidirectional relationship between tourism and real exchange rate. The findings suggest that tourism is the driving force for economic growth, which in turn helps turkey to culminate its current account deficit.

Dhungel [ 15 ] made an effort to investigate causality between tourism and economic growth, In Nepal for the period of (1974–2012), by using Johansen’s cointegration and Error correction model. The result states that unidirectional causality exists in the long run, while in short run no causality exists between two constructs. The study emphasized that strategies should be devised to attain causality running from tourism to economic growth.

Mallick et al. [ 36 ] analyzed the nexus between economic growth and tourism in 23 Indian states over a period of 14 years (1997–2011). Using panel autoregressive distributed lag model based on three alternative estimators such as mean group estimator, pooled mean group and dynamic fixed effects, Research found that tourism exerts positive influence on economic growth in the long run.

Belloumi [ 8 ] examines the causal relationship between international tourism receipts and economic growth in Tunisia by using annual time series data for the period 1970–2007. The study uses the Johansen’s cointegration methodology to analyze the long-run relationship among the concerned variables. Granger causality based Vector error correction mechanism approach indicates that the revenues generated from tourism have a positive impact on economic growth of Tunisia. Thus, the study supports the hypothesis of tourism-driven economic growth, which is specific to developing countries that base their foreign exchange earnings on the existence of a comparative advantage in certain sectors of the economy.

Tang et al. [ 58 ] explored the dynamic Inter-relationships among tourism, economic growth and energy consumption in India for the period 1971–2012. The study employed Bounds testing approach to cointegration and generalized variance decomposition methods to analyze the relationship. The bounds testing and the Gregory-Hansen test for cointegration with structural breaks consistently reveals that energy consumption, tourism and economic growth in India are cointegrated. The study demonstrated that tourism and economic growth have positive impact on energy consumption, while tourism and economic growth are interrelated; with tourism exert significant influence on economic growth. Consequently, this study validates the tourism-led growth hypothesis in the Indian context.

Kadir and Karim [ 24 ]) examined the causal nexus between tourism and economic growth in Malaysia by applying panel time series approach for the period 1998–2005. By applying Padroni’s panel cointegration test and panel Granger causality test, the result indicated both short and long-run relationship. Further, the panel causality shows unidirectional causality directing from tourism receipts to economic growth. The result provides evidence of the significant contribution of tourism industry to Malaysia’s economic growth, thereby justifying the necessity of public intervention in providing tourism infrastructure and facilities.

Antonakakis et al. [ 2 ] test the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe by using a newly introduced spillover index approach. Based on monthly data for 10 European countries over the period 1995–2012, the findings suggested that the tourism–economic growth relationship is not stable over time in terms of both magnitude and direction, indicating that the tourism-led economic growth (TLEG) and the economic-driven tourism growth (EDTG) hypotheses are time-dependent. Thus, the findings of the study suggest that the same country can experience tourism-led economic growth or economic-driven tourism growth at different economic events.

Oh [ 41 ] verifies the contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy by applying Engle and Granger two-stage approach and a bivariate Vector Autoregression model. He claimed that economic expansion lures tourists in the short run only, while there is no such long-run stable relationship between international tourism and economic development in Korea.

Empirical studies have pronouncedly focused on the literature that tourism promotes economic growth. To further substantiate the nexus, the study will investigate the plausible linkages between economic growth and international tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. The inclusion of financial development in the examination of tourism-growth nexus is a unique feature of this study, which have an influencing role in economic growth as financial development has been theoretically and empirically recognized as source of comparative advantage [ 22 ].

This study employs panel ARDL cointegration approach to verify the existence of long-run association among the variables. Further, study estimated the long-run and short-run coefficients of the ARDL model. Subsequently, Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] panel Granger causality test has been employed to check the direction of causality between tourism, financial development and economic growth among BRICS countries.

Database and methodology

Data and variables.

The study is analytical and empirical in nature, which intends to establish the relationship between economic growth and inbound tourism in BRICS countries. For the BRICS countries, limited studies have been conducted depicting the present scenario. Therefore, present study tries to verify the relevance of tourism in economic growth to further enhance the understanding of economic dynamics in BRICS countries. The data used in the study are annual figures for the period stretching from 1995 to 2015, consisting of one endogenous variable (GDP per capita, a proxy for economic growth) and two exogenous variables (international tourism receipts per capita and financial development). The variables employed in the study are based on the economic growth theory, proposed by Balassa [ 4 ], which states that export expansion has a relevant contribution in economic growth. Further, this study incorporates financial development in the model to reduce model misspecification as it is considered to have an influencing role in economic growth both theoretically and empirically [ 22 , 33 ].

The annual data for all the variables have been collected from the World Development Indicators (WDI, 2016) database. The variables used in the study includes gross domestic product per capita (GDP) in constant ($US2010) used as a proxy for economic growth (EG), international tourism receipts per capita (TR) in current US$ as it is widely accepted that the most adequate proxy of inbound tourism in a country is tourism expenditure normally expressed in terms of tourism receipts [ 32 ] and financial development (FD). In line with a recent study on the relationship between financial development and economic growth by Hassan et al. [ 19 ], financial development is surrogated by the ratio of the broad money (M3) to real GDP for all BRICS countries. Here we use the broadest definition of money (M3) as a proportion of GDP– to measure the liquid liabilities of the banking system in the economy. We use M3 as a financial depth indicator, because monetary aggregates, such as M2 or M1, may be a poor proxy in economies with underdeveloped financial systems, because they ‘are more related to the ability of the financial system to provide transaction services than to the ability to channel funds from savers to borrowers’ [ 26 ]. A higher liquidity ratio means higher intensity in the banking system. The assumption here is that the size of the financial sector is positively associated with financial services [ 29 ]. All the variables have been taken into log form.

Unit root test

To verify the long-run relationship between tourism and economic growth through Bounds testing approach, it is necessary to test for stationarity of the variables. The stationarity of all the variables can be assessed by different unit root tests. The study utilizes panel unit root test proposed by Levin et al. [ 35 ] henceforth LLC and Im et al. [ 23 ] henceforth IPS based on traditional augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. The LLC allows for heterogeneity of the intercepts across members of the panel under the null hypothesis of presence of unit root, while IPS allows for heterogeneity in intercepts as well as in the slope coefficients [ 48 ].

Panel ARDL approach to Cointegration

After checking the stationarity of the variables the study employs panel ARDL technique for Cointegration developed by Pesaran et al. [ 23 ]. Pesaran et al. [ 23 ] have introduced the pooled mean group (PMG) approach in the panel ARDL framework. According to Pesaran et al. [ 23 ], the homogeneity in the long-run relationship can be attributed to several factors such as arbitration condition, common technologies, or the institutional development which was covered by all groups. The panel ARDL bounds test [ 46 ] is more appropriate by comparing other cointegration techniques, because it is flexible regarding unit root properties of variables. This technique is more suitable when variables are integrated at different orders but not I (2). Haug [ 20 ] has argued that panel ARDL approach to cointegration provides better results for small sample data set such as in our case. The ARDL approach to cointegration estimates both long and short-run parameters and can be applied independently of variable order integration (independent of whether repressors are purely I (0), purely I(1) or combination of both. The ARDL bounds test approach used in this study is specified as follows:

where Δ is the first-difference operator, \(\alpha_{0}\) stands for constant, t is time element, \(\omega_{1} , \omega_{2} \;\;{\text{and}}\;\; \omega_{3}\) represent the short-run parameters of the model, \(\emptyset_{1} , \emptyset_{2} ,and \emptyset_{3}\) are long-run coefficients, while \(V_{it}\) is white noise error term and lastly, it represents country at a particular time period. In the ARDL model, the bounds test is applied to determine whether the variables are cointegrated or not.

This test is based on the joint significance of F -statistic and the χ 2 statistic of the Wald test. The null hypothesis of no cointegration among the variables under study is examined by testing the joint significance of the F -statistic of \(\omega_{1} , \omega_{2} ,\omega_{3}\) .

In case series variables are cointegrated, an error correction mechanism (ECM) can be developed as Eq. ( 2 ), to assess the short-run influence of international tourism and financial development on economic growth.

where ECT is the error correction term, and \(\varPhi\) is its coefficient which shows how fast the variables attain long-term equilibrium if there is any deviation in the short run. The error correction term further confirms the existence of a stable long-run relationship among the variables.

Panel granger causality test

To examine the direction of causality Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] test is employed. Instead of pooled causality, Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] proposed a causality based on the individual Wald statistic of Granger non-causality averaged across the cross section units. Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] assert that traditional test allows for homogeneous analysis across all panel sets, thereby neglecting the specific causality across different units.

This approach allows heterogeneity in coefficients across cross section panels. The two statistics Wbar-statistics and Zbar-statistics provides standardized version of the statistics and is easier to compute. Wbar-statistic, takes an average of the test statistics, while the Zbar-statistic shows a standard (asymptotic) normal distribution.

They proposed an average Wald statistic that tests the null hypothesis of no causality in a panel subgroup against an alternative hypothesis of causality in at least one panel. Following equations will be used to check the direction of causality between the variables.

Estimation, results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of variables selected for the period 1995–2015. The variable set includes GDP, FD and TR for all BRICS countries. Brazil tops the list with GDP per capita of 4.18, while India lagging behind all BRICS nations. In the recent economic survey by International Monetary Fund (IMF report 2016), India was ranked 126 for its per capita GDP. India’s GDP per capita went up to $7170 against all other BRICS countries which were placed in the above $10,000 bracket. China has the highest tourism receipts in comparison to other BRICS countries. China is a very popular country for foreign tourists, which ranks third after France and USA. In 2014, China invested $136.8 billion into its tourist infrastructure, a figure second only to the United States ($144.3 billion). Tourism, based on direct, indirect, and induced impact, accounted for near 10% in the GDP of China (WTTC report 2017).

Stationarity results

Primarily, we employed LLC and IPS unit root test to assess the integrated properties of the series. The results of IPS and PP tests are presented in Table 2 . Panel unit root test result evinces that FD and TR are stationary at level, while GDP per capita is integrated variable of order 1. The result exemplifies that GDP per capita, Tourism receipts and Financial Development are integrated at 1(0) and 1(1). Consequently, the panel ARDL approach to cointegration can be applied.

Cointegration test results

In view of the above results with a mixture of order integration, the panel ARDL approach to cointegration is the most appropriate technique to investigate whether there exists a long-run relationship among the variables [ 42 ]. Table 3 illustrates that the estimated value of F-statistics, which is higher than the lower and upper limit of the bound value, when InEG is used as a dependent variable. Hence, we reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration \(H_{0 } : \emptyset_{1} = \emptyset_{2} = \emptyset_{3} = 0\) of Eq. ( 1 ). Therefore, the result asserts that international tourism, financial development and economic growth are significantly cointegrated over the period (1995–2015).

Subsequently, the study investigates the long-run and short-run impact of international tourism and financial development on economic growth. Lag length is selected on the principle of minimum Bayesian information criterion (SBC) value, which is 2 in our case. The long-run coefficients of financial development and tourism receipts with respect to economic growth in Table 4 indicate that tourism growth and financial development exerts positive influence on economic growth in the long run. In other words, an increase in volume of tourism receipts per capita and financial depth spurs economic growth and both the coefficients are statistically significant in case of BRICS nations in the long run. The results are interpreted in detail as below:

The elasticity coefficient of economic growth with respect to tourism shows that 1% rise in international tourism receipts per capita would imply an estimated increase of almost 0.31% domestic real income in the long run, all else remaining the same. Thus, the earnings in the form of foreign exchange from international tourism affect growth performance of BRICS nations positively. This finding of our study is in consonance with the empirical results of Kreishan for Jordan [ 30 ], Balaguer and Cantavella-Jordá [ 3 ] for Spain and Ohlan [ 43 ] for India.

Further our finding lend support to the wide applicability of the new growth theory proposed by Balassa which states that export expansion promote growth performance of nations. Thus, validates TLGH coined by Balaguer and Cantavell-Jorda [ 3 ] which states that inbound tourism acts a long-run economic growth factor. The so called tourism-led growth hypothesis suggests that the development of a country’s tourism industry will eventually lead to higher economic growth and, by extension, further economic development via spillovers and other multiplier effects.

Likewise, financial development as expected is found to be positively associated with economic growth. The coefficient of financial development states that 1% improvement in financial development will push up economic growth by 0.22% in the long run, keeping all other variables constant. The empirical results are consistent with the finding of Hassan et al. [ 19 ] for a panel of South Asian countries. Well-regulated and properly functioning financial development enhances domestic production through savings, borrowings & investment activities and boosts economic growth. Further, it promotes economic growth by increasing efficiency [ 7 ]. Levine [ 33 ] believes that financial intermediaries enhance economic efficiency, and ultimately growth, by helping allocation of capital to its best use. Modern growth theory identifies two specific channels through which the financial sector might affect long-run growth; through its impact on capital accumulation and through its impact on the rate of technological progress. The sub-prime crisis which depressed the economic growth worldwide in 2007 further substantiates the growth-financial development nexus.

In the third and final step of the bounds testing procedure, we estimate short-run dynamics of variables by estimating an error correction model associated with long-run estimates. The empirical finding indicates that the coefficient of error correction term (ECT) with one period lag is negative as well as statistically significant. This finding further substantiates the earlier cointegration results between tourism, financial development and economic growth, and indicates the speed of adjustment from the short-run toward long-run equilibrium path. The coefficient of ECT reveals that the short-run divergences in economic growth from long-run equilibrium are adjusted by 43% every year following a short-run shock.

The short-run parameters in Table 5 demonstrates that tourism and financial development acts as an engine of economic growth in the short run as well. The coefficient of both tourism receipts per capita and financial development with one period lag is also found to be progressive and significant in the short run. These results highlight the role of earnings from international tourism and financial stability as an important driving force of economic growth in BRICS nations in the short run as well.

Further, a comparison between short-run and long-run elasticity coefficients evince that long-run responsiveness of economic growth with respect to tourism and financial development is higher than that of short run. It exemplifies that over time higher international tourism receipts and well-regulated financial system in BRICS nations give more boost to economic growth.

Analysis of causality

At this stage, we investigate the causality between tourism, financial development and economic growth presented in Table 6 . The result shows bi-directional causal relationship between tourism and economic growth, thereby validates ‘feedback hypothesis’ and consequently supported both the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) and its reciprocal, the economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis (EDTH). The bi-directional causality between inbound tourism and GDP, which directs the level of economic activity and tourism growth, mutually influences each other in that a high volume of tourism growth leads to a high level of economic development and reverse also holds true. These results replicate the findings of Banday and Ismail [ 5 ] in the context of BRICS countries, Yazdi et al. [ 27 ] for Iran and Kim et al. [ 28 ] for Taiwan. One of the channels through which tourism spurs economic growth is through the use of receipts earned in the form of foreign currency. Thus, growth in foreign earnings may allow the import of technologically advances goods that will favor economic growth and vice versa. Thus, results demonstrate that international tourism promotes growth and in turn economic expansion is necessary for tourism development in case of BRICS countries. With respect to policy context, this finding suggests that the BRICS nations should focus on economic policies to promote tourism as a potential source of economic growth which in turn will further promote tourism growth.

Similarly, in case of economic growth and financial development, the findings demonstrate the presence of bi-directional causality between two constructs. The findings validate thus both ‘demand following’ and supply leading’ hypothesis. The findings suggests that indeed financial development plays a crucial role in promoting economic activity and thus generating economic growth for these countries and reverse also holds. Our findings are in line with Pradhan [ 48 ] in case of BRICS countries and Hassan et al. [ 19 ] for low and middle-income countries. This suggests that finance development can be used as a policy variable to foster economic growth in the five BRICS countries and vice versa. The study emphasizes that the current economic policies should recognize the finance-growth nexus in BRICS in order to maintain sustainable economic development in the economy. The empirical results in this paper are in line with expectations, confirming that the emerging economies of the BRICS are benefiting from their finance sectors.

Finally, two-sided causal relationship is found between tourism receipts and financial development. That is, tourism might contribute to financial development and, in return, financial development may positively contribute to tourism. This means that financial depth and tourism in BRICS have a reinforcing interaction. The positive impact of tourism on financial development can be attributed to the fact that inflows of foreign exchange via international tourism not only increases income levels but also leads to rise in official reserves of central banks. This in turn enables central banks to adapt expansionary monetary policy. The positive contribution of financial sector to tourism is further characterized by supply leading hypothesis. Further, better financial and market conditions will attract tourism entrepreneurship, because firms will be able to use more capital instead of being forced to use leveraging [ 13 ]. Hence, any shocks in money supply could adversely affect tourism industry in these countries. Song and Lin [ 56 ] found that global financial crisis had a negative impact on both inbound and outbound tourism in Asia. This result is in consistent with Başarir and Çakir [ 6 ] for Turkey and four European countries.

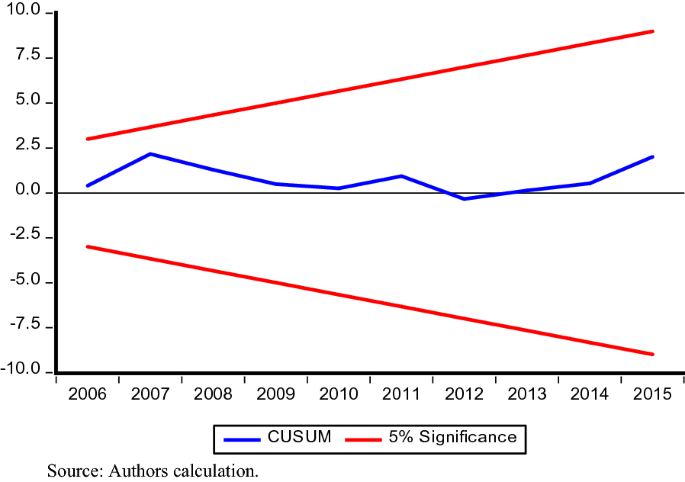

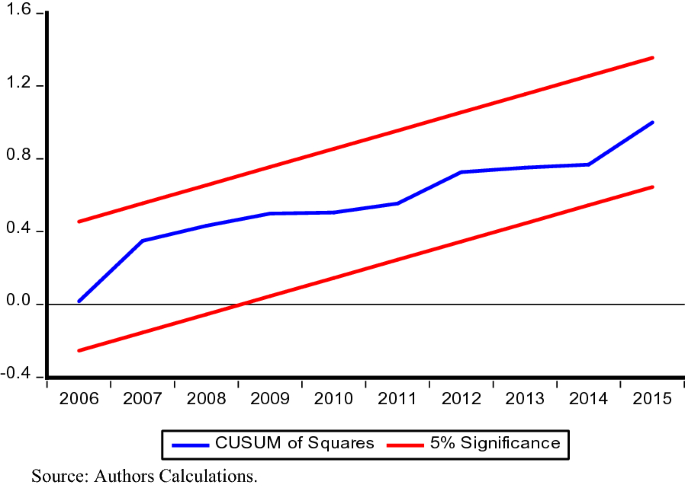

Stability tests

In addition, to test the stability of parameters estimated and any structural break in the model CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests are employed. Figs. 1 and 2 show blue line does not transcend red lines in both the tests, thus provides strong evidence that our estimated model is fit and valid policy implications can be drawn from the results.

Plot of CUSUM

Plot of CUSUMQ

Summary and concluding remarks

A rigorous study of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, through the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) perspective has remained a debatable issue in the economic growth literature. This study aims to empirically investigate the relationship between inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth in BRICS countries by utilizing the panel data over the period 1995–2015. The study employs the panel ARDL approach to cointegration and Dumitrescu-Hurlin panel Granger causality test to detect the direction of causation.

To the best of authors’ knowledge, this is the first study which explored the relationship between economic growth and tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. The empirical results of ARDL model posits that in BRICS countries inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth are significantly cointegrated, i.e., variables have stable long-run relationship. This methodology has allowed obtaining elasticities of economic growth with respect to tourism and financial development both in the long run and short run. The result reveals that international tourism growth and financial development positively affects economic growth both in the long run and short run. The coefficient of tourism indicates that with a 1% rise in tourism receipts per capita, GDP per capita of BRICS economies will go up by 0.31% in the long run. This finding lends support to TLGH coined by Balaguer and Cantavell-Jorda [ 3 ] which states that inbound tourism acts a long-run economic growth factor. The so called tourism-led growth hypothesis suggests that the development of a country’s tourism industry will eventually lead to higher economic growth and, by extension, further economic development via spillovers and other multiplier effects.

Likewise, 1% improvement in financial development, on average, will increase economic growth in BRICS countries by 0.22% in the long run. The result seems logical as modern growth theory identifies two channels through which the financial sector might affect long-run growth: first, through its impact on capital accumulation and secondly, through its impact on the rate of technological progress. The sub-prime crisis which hit the economic growth Worldwide in 2007 further substantiates the growth-financial development nexus.

The negative and statistically significant coefficient of lagged error correction term (ECT) further substantiates the long-run equilibrium relationship among variables. The negative coefficient of ECT also shows the speed of adjustment toward long-run equilibrium is 43% per annum if there is any short-run deviation. The estimates of parameters are found to be stable by applying CUSUM and CUSUMQ for the time period under consideration. Therefore, inbound tourism earnings and financial institutions can be used as a channel to increase economic growth in BRICS economies.

Further, Granger causality test result indicates the bi-directional causation in all cases. Hence, the causal relationship between international tourism and economic growth is bi-directional. And, consequently this empirical finding lends support to both the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) and its reciprocal, the economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis (EDTH). This means that tourism is not only an engine for economic growth, but the economic outcome on itself can play an important role in providing growth potential to tourism sector.

The Granger causality findings provide useful information to governments to examine their economic policy, to adjust priorities regarding economic investment, and boost their economic growth with the given limited resources. Thus, it is suggested that more resources should be allocated to tourism industry and tourism-related industries if the tourism-led growth hypothesis holds true. On the other side, if economic-driven tourism growth is supported then more resources should be diverted to leading industries rather than the travel and tourism sector, and the tourism industry will in turn benefit from the resulting overall economic growth. And, when bi-directional causality is detected, a balanced allocation of economic resources for the travel and tourism sector and other industries is important and necessary. The policy implication is that resource allocation supporting both the tourism and tourism-related industries could benefit both tourism development and economic growth.

To sum up, the major finding of this study lends support to wide applicability of the tourism-led growth hypothesis in case of BRICS countries. Thus, in the Policy context, significant impact of tourism on BRICS economy rationalizes the need of encouraging tourism. Tourism can spur economic prosperity in these countries and for this reason; policymakers should give serious consideration toward encouraging tourism industry or inbound tourism. BRICS countries should focus more on tourism infrastructure, such as, convenient transportation, alluring destinations, suitable tax incentives, viable hostels and proper security arrangements to attract the potential tourists. Most of these countries are devoid of rich facilities and popular tourist incentives, to get promoted as important destination and in the long-run promotes economic growth. Further, they need a staunch support from all sections of authorities, non-government organizations (NGOs), and private and allied industries, in the endeavor to attain sustainable growth in tourism. Both state and non-state actors must recognize this growing industry and its positive implication on economy.

For future research, we suggest that researchers should consider the nonlinear factor in the dynamic relationship of tourism and economic growth in case of BRICS countries. Further one can go for comparative study to examine the TLGH in BRICS countries.

Availability of data and materials

Data used in the study can be provided by the corresponding author on request.

There are no fixed definitions of short, medium and long run and generally in macroeconomics, short run can be viewed as 1 to 2 or 3 years, medium up to 5 years and long run from 5 years to 20 or 25 years.

Abbreviations

autoregressive distributed lag model

Brazil, Russia, India, China and South-Africa

United Nations World Tourism Organization

World Travel & Tourism Council

gross domestic product

world development indicators

tourism-led growth hypothesis

export-led growth hypothesis

economic-driven tourism hypothesis

augmented Dickey–Fuller test

error correction model

error correction term

Andriotis K (2002) Scale of hospitality firms and local economic development—evidence from Crete. Tourism Manag 23(4):333–341

Google Scholar

Antonakakis N, Dragouni M, Filis G (2015) How strong is the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe? Econ Modell 44:142–155

Balaguer J, Cantavella-Jorda M (2002) Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: the Spanish case. Appl Econ 34(7):877–884

Balassa B (1978) Exports and economic growth: further evidence. J Dev Econ 5(2):181–189

Banday UJ, Ismail S (2017) Does tourism development lead positive or negative impact on economic growth and environment in BRICS countries? A panel data analysis. Econ Bull 37(1):553–567

Basarir C, Çakir YN (2015) Causal interactions between CO 2 emissions, financial development, energy and tourism. Asian Econ Financ Rev 5(11):1227

Bell C, Rousseau PL (2001) Post-independence India: a case of finance-led industrialization? J Dev Econ 65(1):153–175

Belloumi M (2010) The relationship between tourism receipts, real effective exchange rate and economic growth in Tunisia. Int J Tour Res 12(5):550–560

Blake A, Sinclair MT, Soria JAC (2006) Tourism productivity: evidence from the United Kingdom. Ann Tourism Res 33(4):1099–1120

Brida JG, Pulina M (2010) A literature review on the tourism-led-growth hypothesis. Working paper CRENoS201017. Centre for North South Economic Research, Sardinia

Brida JG, Cortes-Jimenez I, Pulina M (2016) Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Curr Issues Tourism 19(5):394–430

Chatziantoniou I, Filis G, Eeckels B, Apostolakis A (2013) Oil prices, tourism income and economic growth: a structural VAR approach for European Mediterranean countries. Tourism Manag 36:331–341

Chen M-H (2010) The economy, tourism growth and corporate performance in the Taiwanese hotel industry. Tourism Manag 31:665–675

Croes R (2006) A paradigm shift to a new strategy for small island economies: embracing demand side economics for value enhancement and long term economic stability. Tourism Manag 27:453–465

Dhungel KR (2015) An econometric analysis on the relationship between tourism and economic growth: empirical evidence from Nepal. Int J Econ Financ Manag 3(2):84–90

Dumitrescu EI, Hurlin C (2012) Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ Modell 29(4):1450–1460

Daniel Mminele (2016) The role of BRICS in the global economy. Speech at the Bundesbank Regional Office in North Rhine-Westphalia, Düsseldorf, Germany. https://www.bis.org/review/r160720c.pdf

Goldsmith RW (1969) Financial structure and development (No. HG174 G57)

Hassan MK, Sanchez B, Yu JS (2011) Financial development and economic growth: new evidence from panel data. Quart Rev Econ Financ 51(1):88–104

Haug AA (2002) Temporal aggregation and the power of cointegration tests: A Monte Carlo study. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 64:399–412

Henry EW, Deane B (1997) The contribution of tourism to the economy of Ireland in 1990 and 1995. Tourism Manag 18(8):535–553

Hur J, Raj M, Riyanto YE (2006) Finance and trade: a cross-country empirical analysis on the impact of financial development and asset tangibility on international trade. World Dev 34(10):1728–1741

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2003) Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econ 115(1):53–74

Kadir N, Karim MZA (2012) Tourism and economic growth in Malaysia: evidence from tourist arrivals from Asean-S countries. Econ Res Ekonomska istraživanja 25(4):1089–1100

Katircioglu S (2009) Testing the tourism-led growth hypothesis: the case of Malta. Acta Oeconomica 59(3):331–343

Khan M, Senhadji A (2003) Financial development and economic growth: a review and new evidence. J Afr Econ 12:89–110

Khoshnevis Yazdi S, Homa Salehi K, Soheilzad M (2017) The relationship between tourism, foreign direct investment and economic growth: evidence from Iran. Curr Issues Tourism 20(1):15–26

Kim HJ, Chen MH (2006) Tourism expansion and economic development: the case of Taiwan. Tourism Manag 27(5):925–933

King R, Levine R (1993) Finance, entrepreneurship, and growth: theory and evidence. J Monet Econ 32:513–542

Kreishan FM (2010) Tourism and economic growth: the case of Jordan. Eur J Soc Sci 15:229–234

Krueger A (1980) Trade policy as an input to development. Am Econ Rev 70:188–292

Kumar RR (2014) Exploring the role of technology, tourism and financial development: an empirical study of Vietnam. Qual Quant 48(5):2881–2898

Levine R (1997) Financial development and economic growth: views and agenda. J Econ Lit 35(2):688–726

Lee CC, Chang CP (2008) Tourism development and economic growth: a closer look at panels. Tourism Manag 29(1):180–192

Levin A, Lin CF, Chu CSJ (2002) Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J Econ 108(1):1–24

Mallick L, Mallesh U, Behera J (2016) Does tourism affect economic growth in Indian states? Evidence from panel ARDL model. Theor Appl Econ 23(1):183–194

Mastny L (2001) Treading lightly: new paths for international tourism. In: Peterson JA (ed) World Watch Paper 159. World Watch Institute

McKinnon RI (1964) Foreign exchange constraints in economic development and efficient aid allocation. Econ J 74(294):388–409

McKinnon RI (1973) Money and capital in economic development. The Brookings Institution, Washington

Narayan PK (2004) Economic impact of tourism on Fiji’s economy: empirical evidence from the computable general equilibrium model. Tourism Econ 10(4):419–433

Oh CO (2005) The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tourism Manag 26(1):39–44

Ohlan R (2015) The impact of population density, energy consumption, economic growth and trade openness on CO 2 emissions in India. Nat Hazards 79(2):1409–1428

Ohlan R (2017) The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Bus J 3(1):9–22

Parrilla JC, Font AR, Nadal JR (2007) Tourism and long-term growth a Spanish perspective. Ann Tourism Res 34(3):709–726

Payne JE, Mervar A (2010) Research note: the tourism-growth nexus in Croatia. Tourism Econ 16(4):1089–1094

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16(3):289–326

Po WC, Huang BN (2008) Tourism development and economic growth—a nonlinear approach. Phys A Stat Mech Appl 387(22):5535–5542

Pradhan RP, Dasgupta P, Bele S (2013) Finance, development and economic growth in BRICS: a panel data analysis. J Quant Econ 11(1–2):308–322

Ridderstaat J, Oduber M, Croes R, Nijkamp P, Martens P (2014) Impacts of seasonal patterns of climate on recurrent fluctuations in tourism demand: evidence from Aruba. Tourism Manag 41:245–256

Schumpeter JA (1911) The theory of economic development: an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, p 1934

Shaw ES (1973) Financial deepening in economic development. Oxford University Press, London

Sugiyarto G, Blake A, Sinclair MT (2003) Tourism and globalization: economic impact in Indonesia. Ann Tourism Res 30(3):683–701

Szivas E, Riley M (1999) Tourism employment during economic transition. Ann Tourism Res 26(4):747–771

Savaş B, Beşkaya A, Şamiloğlu F (2010) Analyzing the impact of international tourism on economic growth in Turkey. Uluslararası Yönetim İktisat ve İşletme Dergisi 6(12):121–136

Schubert SF, Brida JG, Risso WA (2011) The impacts of international tourism demand on economic growth of small economies dependent on tourism. Tourism Manag 32(2):377–385

Song H, Lin S (2010) Impacts of the financial and economic crisis on tourism in Asia. J Travel Res 49(1):16–30

Tang CF (2013) Temporal Granger causality and the dynamics relationship between real tourism receipts, real income and real exchange rates in Malaysia. Int J Tourism Res 15(3):272–284

Tang CF, Tiwari AK, Shahbaz M (2016) Dynamic inter-relationships among tourism, economic growth and energy consumption in India. Geosyst Eng 19(4):158–169

United Nations World Tourism Report (2014) Annual report 2014

World Travel & Tourism Council (2012) Travel & Tourism Economic Impact. World, London: World Travel & Tourism Council.

World Travel and Tourism Council (2016) Global travel and tourism economic impact update August 2016

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This research has received no specific funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

Haroon Rasool & Md. Tarique

Department of Commerce, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

Shafat Maqbool

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HR has written introduction, research methodology and results and discussion part. Review of literature and data analysis was done by SM. Conclusion was written jointly by HR and SM. MT has provided useful inputs and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Haroon Rasool .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

Authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rasool, H., Maqbool, S. & Tarique, M. The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis. Futur Bus J 7 , 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00048-3

Download citation

Received : 02 August 2019

Accepted : 30 November 2020

Published : 05 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00048-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic growth

- Inbound tourism

- Financial development

- Cointegration

- Panel granger causality

JEL Classification

Tourism multiplier effect

The concept of tourism multiplier effect has been gaining traction in recent years. Certainly, the tourism industry has a multiplier effect that extends beyond the direct spending by tourists. This multiplier effect creates jobs, stimulates economic growth, and promotes community development.

What is the tourism multiplier effect?

The tourism multiplier effect refers to how many times the money spent by a tourist circulates in the country’s economy (Byju’s, 2023). Broadly, it refers to the economic impact of tourism that extends beyond the initial spending by visitors.

When tourists spend money, it creates a ripple effect that stimulates economic activity in various sectors. This multiplier effect can be quantified by measuring the direct and indirect effects of tourism on the economy.

The multiplier effect occurs because the money spent by tourists does not only benefit the businesses that directly serve tourists, but also spreads throughout the local economy. This effect can be seen in a wide range of industries, including transportation, accommodation, food and beverage, and retail.

The tourism multiplier effect is especially important for countries that rely heavily on tourism as a source of revenue. For example, tourism accounts for more than 28% of the GDP of Maldives (Michigan State University, 2023).

Likewise, tourism and related services contribute approximately 70 percent to the GDP of Bahamas and employs over half of the workforce (ITA, 2022). Therefore, understanding the tourism multiplier effect is essential for policymakers and stakeholders in the tourism industry.

Types of tourism multipliers

There are two types of tourism multipliers: direct and indirect. Direct multipliers refer to the initial spending by visitors, such as accommodation, food, and transportation. Indirect multipliers refer to the subsequent spending by businesses that supply goods and services to the tourism industry.

For example, a hotel that purchases food from a local supplier creates indirect economic activity for the supplier. The local suppliers that provide food to hotels and restaurants may experience an increase in sales during peak tourism season, which can lead to the hiring of additional staff and a boost in tax revenue for the local government.

The tourism multiplier effect also creates induced multipliers, which refer to the spending by employees and business owners who benefit from the direct and indirect effects of tourism. For example, a hotel employee who earns a salary spends money on goods and services, which creates additional economic activities.

The economic effects of tourism on local businesses

The tourism industry can have a significant impact on local businesses. When tourists spend money on goods and services, it creates income for local businesses. This income can be reinvested in the local economy, creating a multiplier effect that stimulates economic growth.

However, the tourism industry can also have negative effects on local businesses. For example, if a large hotel chain opens in a small town, it can put small local hotels out of business. Therefore, policymakers must balance the benefits and costs of tourism to ensure that local businesses are not negatively impacted.

Jobs created by the tourism industry

The tourism industry is a significant source of employment for many countries. In some countries, such as Maldives and Bahamas, it is indeed the primary source of employment.

The jobs created by the tourism industry can vary from low-skilled to high-skilled positions, such as tour guides, hotel managers, and chefs. These jobs provide opportunities for people with different levels of education and skills.

The number of jobs created by tourism depends on the level and type of activities. For example, a large-scale resort may create thousands of jobs, while a small bed and breakfast may only create a few jobs.

The total number of tourism employees in the USA is around 6 million (IBISWorld, 2023). Tourism supports around 3.8 million jobs in the UK. Just imagine the impact of the spending of all these people on the economy!

Community development from tourism

Tourism can promote community development by generating income and creating jobs. This income can be used to improve infrastructure, support local businesses, and invest in community projects.

For example, a city that attracts a large number of tourists may use the tax revenue generated by tourism to improve public transportation or build new community facilities.

Tourism can also have a cultural impact on local communities. It can promote cultural exchange and understanding, as tourists learn about local customs and traditions. This can help to preserve and promote local culture, which can have a positive impact on the community.

Environmental impact of tourism

Tourism can have a positive environmental impact. It can promote conservation and the protection of natural resources. For example, a national park that attracts tourists may receive funding for conservation efforts, which can help to preserve the park’s ecosystem.

However, tourism can also have a negative impact on the environment. The construction of new hotels and resorts can lead to deforestation, habitat destruction, and pollution. Tourists can also contribute to environmental degradation by generating waste and consuming natural resources.