- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Wolf ecology basics.

NPS Photo / Steve Arthur

Leaving Home

NPS Photo / Nathan Kostegian

Leader of the Pack

- Leading pack travel

- Scent marking

- Food ownership

Wolf Territories

Wolves in parks.

Learn more about wolves and wolf research at Denali National Park, in Alaska.

Learn about wolves and wolf research at Yellowstone National Park

Learn more about wolves and wolf research at Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, in Alaska.

Learn more about wolves and wolf research at Lake Clark National Park, in Alaska.

Learn more about wolves and wolf research at Voyageurs National Park, in Minnesota.

Learn more about wolves and wolf research at Isle Royale National Park, in Michigan.

Last updated: October 22, 2021

Do the Oldest and Weakest Wolves Really Lead the Pack?

A photograph of a wolf pack is commonly shared with an inaccurate description of the behavior of wolves., published dec. 21, 2015.

About this rating

In December 2015, a photograph of a wolf pack marching through the snow began circulating via Facebook along with an inaccurate description about its hierarchy:

"A wolf pack: the first 3 are the old or sick, they give the pace to the entire pack. If it was the other way round, they would be left behind, losing contact with the pack. In case of an ambush they would be sacrificed. Then come 5 strong ones, the front line. In the center are the rest of the pack members, then the 5 strongest following. Last is alone, the alpha. He controls everything from the rear. In that position he can see everything, decide the direction. He sees all of the pack. The pack moves according to the elders pace and help each other, watch each other."

While we don't know exactly who penned the dubious description attached to the picture, the earliest iteration we've found so far came from an Italian-language Facebook post dated 17 December 2015. This post was translated into English on 20 December 2015 and quickly went viral. -->

Despite the image's popularity, however, the attached description of the inner workings of a wolf pack are inaccurate.

The photograph shown was taken by Chadden Hunter and featured in the BBC documentary Frozen Planet in 2011, with its original description explaining that the "alpha female" led the pack and that the rest of the wolves followed in her tracks in order to save energy:

A massive pack of 25 timberwolves hunting bison on the Arctic circle in northern Canada. In mid-winter in Wood Buffalo National Park temperatures hover around -40°C. The wolf pack, led by the alpha female, travel single-file through the deep snow to save energy. The size of the pack is a sign of how rich their prey base is during winter when the bison are more restricted by poor feeding and deep snow. The wolf packs in this National Park are the only wolves in the world that specialize in hunting bison ten times their size. They have grown to be the largest and most powerful wolves on earth.

While this description is more accurate than the one shared in the viral Facebook post, some researchers would nonetheless dispute the use of the term "alpha." In David Mech's 1999 paper "Alpha Status, Dominance, and Division of Labor in Wolf Packs," he argued that the concept of an "alpha" wolf who asserts his or her dominance over other pack members doesn't actually exist in the wild:

Labeling a high-ranking wolf alpha emphasizes its rank in a dominance hierarchy. However, in natural wolf packs, the alpha male or female are merely the breeding animals, the parents of the pack, and dominance contests with other wolves are rare, if they exist at all. During my 13 summers observing the Ellesmere Island pack, I saw none. Thus, calling a wolf an alpha is usually no more appropriate than referring to a human parent or a doe deer as an alpha. Any parent is dominant to its young offspring, so "alpha" adds no information. Why not refer to an alpha female as the female parent, the breeding female, the matriarch, or simply the mother? Such a designation emphasizes not the animal's dominant status, which is trivial information, but its role as pack progenitor, which is critical information.

This photograph is "real" in the sense that it shows a pack of wolves in Wood Buffalo National Park, but the pack is not being led by the three oldest members and trailed by an "alpha" wolf, as implied by a viral Facebook post. Instead, one of the stronger animals leads the group in order to create a path through the snow for them.

Mech, L. David. "Alpha Status, Dominance, and Division of Labor in Wolf Packs." Canadian Journal of Zoology 77:1196-1203 (1999).

By Dan Evon

Dan Evon is a former writer for Snopes.

Article Tags

Wolf Facts: Gray Wolves, Timber Wolves & Red Wolves

Wolves are large carnivores — the largest member of the dog, or Canid, family. Wolves are common to all parts of the Northern Hemisphere. They are usually shy and cautious around humans, but unlike the dog, have not been domesticated at all.

There are three species and close to 40 subspecies of wolf, according to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS), so they come in many different sizes. The most common type of wolf is the gray wolf, or timber wolf. Adult gray wolves are 4 to 6.56 feet (120 to 200 centimeters) long and weigh about 40 to 175 lbs. (18 to 79 kilograms). As its name indicates, the gray wolf typically has thick gray fur, although pure white or all black variations exist.

Another species, the red wolf, is a bit smaller. They grow to around 4.5 to 5.5 feet long (137 to 168 cm) and weigh 50 to 80 lbs. (23 to 36 kg), according to the Defenders of Wildlife organization.

Wolves are found in North America, Europe, Asia and North Africa. They tend to live in the remote wilderness, though red wolves prefer to live in swamps, coastal prairies and forests. Many people think wolves live only in colder climates, but wolves can live in temperatures that range from minus 70 to 120 degrees F (minus 50 to 48.8 degrees C), according to the San Diego Zoo .

The Eastern wolf — also known as Great Lakes wolf, Eastern timber wolf, Algonquin wolf or deer wolf — has been deemed a distinct species from their Western cousins, according to a review by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service scientists. Eastern wolves used to live in the northeastern United States, but now remain only in southeastern Canada.

In 2016, the Center Biological Diversity filed a notice of intent to sue the Fish and Wildlife Service to protect red wolves in the United States. According to research published in the journal Science Advances in 2016, though, there is only one type of wolf in North America. DNA testing found that only gray wolves are found on the continent. The research also found that red wolves and Eastern wolves may be hybrids of grey wolves and coyotes.

Wolves hunt and travel in packs. Packs don't consist of many members, though. Usually, a pack will have only one male and female and their young. This usually means about 10 wolves per pack, though packs as large as 30 have been recorded.

Packs have a leader, known as the alpha male. Each pack guards its territory against intruders and may even kill other wolves that are not part of their pack. Wolves are nocturnal and will hunt for food at night and sleep during the day.

Wolves are voracious eaters. They can eat up to 20 lbs. (9 kg) of food during one meal. Since they are carnivores, their meals consist of meat that they have hunted.

Gray wolves usually eat large prey such as moose, goats, sheep and deer. Normally, the pack of wolves will find the weakest or sickest animal in a herd, circle it and kill it together. Wolves are known to attack and kill domestic animals as well as animals they find in the wild.

Red wolves eat smaller prey such as rodents, insects and rabbits. They aren't afraid of going outside their carnivorous diet and will eat berries on occasion, too.

Young wolves are called pups. The leader of the pack and his female mate are usually the only ones in a pack that will have offspring. They mate in late winter. The female has a gestation period of nine weeks and gives birth to a litter consisting of one to 11 pups.

When the pups are born, they are cared for by all of the adult wolves in the pack. Young pups start off drinking milk from their mother, but around five to 10 weeks they will start eating food regurgitated from adult pack members.

At six months, wolf pups become hunters, and at 2 years old they are considered adults. On average, a wolf will live four to eight years in the wild.

Classification/taxonomy

This the classification of wolves, according to ITIS:

Kingdom : Animalia Subkingdom : Bilateria Infrakingdom : Deuterostomia Phylum : Chordata Subphylum : Vertebrata Infraphylum : Gnathostomata Superclass : Tetrapoda Class : Mammalia Subclass : Theria Infraclass : Eutheria Order : Carnivora Suborder : Caniformia Family : Canidae Genus : Canis Species :

- Canis lupus (gray wolf)

- Canis rufus (red wolf)

- Canis lycaon (Eastern wolf)

Conservation status

Though wolves once roamed far and wide, they are very scarce today. The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) lists red wolves as critically endangered. According to the National Parks Conservation Association, there are 20 to 80 red wolves currently living in the wild.

The Ethiopian wolf is also listed as endangered by the IUCN. The Eastern wolf is threatened and is protected in Canada.

Other facts

Packs of wolves don't like to stay in one place. They are known to travel as far as 12 miles (20 kilometers) per day.

Wolves have friends. Wolves howl to communicate with other members of the pack. Researchers have found that they howl more to pack members that they spend the more time with.

There are many names for gray wolves. Besides timber wolf, they are also called common wolf, tundra wolf, Mexican wolf and plains wolf.

To help with the red wolf population, wild wolves are given pups that are born in captivity. This is called "fostering."

Wolves also communicate by leaving scent marking such as urine or feces on a trail.

Wolves are very similar to dogs in behavior. They love to play, chew on bones but will growl or snarl when threatened.

Other resources

- National Geographic: Wolf

- World Wildlife Federation: Arctic Wolf

- World Wildlife Federation: Gray Wolf

- BBC Nature: Wolf

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Why do dogs sniff each other's butts?

Hammer-headed bat: The African megabat that looks like a gargoyle and holds honking pageants

Japan captures 1st image of space debris from orbit, and it's spookily stunning

Most Popular

- 2 Key events in the Bible, such as the settlement and destruction of Jerusalem, confirmed using radiocarbon dating

- 3 Why do most mammals have 5 fingers?

- 4 'Lost' satellite finally found after orbiting undetected for 25 years

- 5 'Major lunar standstill' may reveal if Stonehenge is aligned with the moon

- 2 Why do most mammals have 5 fingers?

- 3 'Major lunar standstill' may reveal if Stonehenge is aligned with the moon

- 4 Siberia's 'gateway to the underworld' is growing a staggering amount each year

- The Social Wolf

Family Groups (or Packs) The Bond Sharing Knowledge The Wolf You Know The Lone Wolf

Wolves are complex, highly intelligent animals who are caring, playful, and above all devoted to family. Only a select few other species exhibit these traits so clearly. Just like elephants, gorillas and dolphins, wolves educate their young, take care of their injured and live in family groups.

Family Groups

A wolf pack is an exceedingly complex social unit—an extended family of parents, offspring, siblings, aunts, uncles, and sometimes dispersers from other packs. There are old wolves that need to be cared for, pups that need to be educated, and young adults that are beginning to assert themselves – all altering the dynamics of the pack.

The job of maintaining order and cohesion falls largely to the alphas, also known as the breeding pair. Typically, there is only one breeding pair in a pack. They, especially the alpha female (the mother of the pack), are the glue keeping the pack together. The loss of a parent can have a devastating impact on social group cohesion. In small packs, human-caused mortality of the alpha female and/or the alpha male can cause the entire pack to dissolve.

After the alphas, wolves second in command are called the betas, followed by mid-ranking wolves, and finally the omegas. Both mid- and low-ranking positions are somewhat fluid. Although an omega may hold that position for many years, it is not unheard of for the pack to pick a new omega and let the other retire.

Living in a pack not only facilitates the raising and feeding of pups, coordinated and collaborative hunting, and the defense of territory, it also allows for the formation of many unique emotional bonds between pack members, the foundation for cooperative living.

Wolves care for each other as individuals. They form friendships and nurture their own sick and injured. Pack structure enables communication, the education of the young and the transfer of knowledge across generations. Wolves and other highly social animals have and pass on what can be best described as culture. A family group can persevere for several generations, even decades, carrying knowledge and information through the years, from generation to generation.

Wolves play together into old age, they raise their young as a group, and they care for injured companions. When they lose a pack mate, there is evidence that they suffer and mourn that loss. When we look at wolves, we are looking at tribes—extended families, each with its own homeland, history, knowledge, and indeed, culture.

Sharing Knowledge:

Wolves communicate, collaborate and share knowledge across generations. The older wolves, as more experienced hunters, share hunting strategies and techniques with younger wolves, passing down knowledge from one generation to the next, maintaining a culture unique to that pack.

The late biologist Gordon Haber observed wolves changing their hunting strategy based on weather, terrain, and prey behavior. Read about Gordon’s research here .

The Lone Wolf:

We often hear the phrase “lone wolf,” an expression of grudging admiration. A lone wolf is often viewed as a rugged individualist, uncompromising and independent, driven to forge his own path, unfettered by the sentimental need for companionship. In reality, few people would ever want to live this way—and, as it turns out, few wolves would either. Wolves, males and females alike, may go through periods alone, but they’re not interested in lives of solitude. A lone wolf is a wolf that is searching, and what it seeks is another wolf. Everything in a wolf’s nature tells it to belong to something greater than itself: a pack. Like us, wolves form friendships and maintain lifelong bonds. They succeed by cooperating, and they struggle when they’re alone. Like us, wolves need one another . Read more…

The Wolf You Know

In our dog companions, we recognize the face, a broad mask that tapers gracefully into a long muzzle. we have looked into the eyes, bright with curiosity. we understand the messages conveyed through posture: the alertness seen in expression, the playfulness of a bow, the confidence or fear betrayed by an animated tail. we can be forgiven for thinking we already know the wolf, for in many ways we already do..

Genetics leaves little doubt that domestic dogs, our canine companions, are descended from wolves. The DNA of any dog is almost exactly the same as that of a wolf.

You can see a lot of your dog in a wolf and a lot of wolf in your dog. They are both social animals. Just like elephants, gorillas and whales, they educate their young, take care of their injured and live in family groups.

The traits that wolves passed on to dogs served us well as we became shepherds and farmers. We capitalized on the wolf’s territorialism to create a dog that steadfastly guarded our flocks and property. We put the wolf’s superior sense of smell and knack for locating prey to use as trackers and retrievers on our own hunts. We transformed the wolf’s skill at harassing and maneuvering big grazing animals into a herding instinct, helping us move our livestock from place to place.

The wolf also passed along to dogs its most indispensable qualities: devotion to its pack, sociability, and a capacity for learning, communication, and expression.

In turning the wolf into the dog, we created the ultimate companion, a faithful friend that can understand our intentions even better than our fellow primates can.

Both wolves and humans brought unique, complementary talents to a relationship that was based on mutual respect. Several scholars agree that humans learned to hunt from wolves.

The relationship between dogs and humans has been so mutually beneficial and enduring that it is clear that we influenced each other’s evolution.

Knowing all that the wolf bequeathed to our beloved dogs, how strange that we reserve for wolves a special hatred that we hold for no other animal.

We brought our domestic dogs along with us, into our pastures, cities and homes.

Wolves are the dogs that stayed behind, favoring their wild ways. Perhaps we can’t forgive them for that.

Living with Wolves Museum 580 4th St, Suite 150 Ketchum, ID 83340 208-928-4991

Hours of Operation Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 4pm

A 501(c)3 nonprofit organization Tax ID: 20-4933982

© 2024 Living with Wolves. / 501c3 Non-Profit Organization design by Glick + Fray Privacy Policy

- Visit Our Museum

- Interactive Exhibit

- Meet the Wolf

- How Wolves Hunt

- Wolves & Our Ecosystem

- The Language of Wolves

- Four Perceptions

- Tackling the Myths

- Killing Wolves

- Ranching Solutions

- Educational Resources

- Meet the Pack

- Sawtooth Pack Stories

- Our Observations

- Saying Goodbye

- Our Mission

- Our History

- Our Organization

- Annual Reports

- Programs & Outreach

- Nat Geo Partnership

- Testimonials

- Wolves Need Your Help

- LWW Endowment

- Who to Contact

- Stay Informed

Elephant Cam

See the Smithsonian's National Zoo's Asian elephants — Spike, Bozie, Kamala, Swarna and Maharani — both inside the Elephant Community Center and outside in their yards.

Now more than ever, we need your support. Make a donation to the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute today!

Become a Member

Members are our strongest champions of animal conservation and wildlife research. When you become a member, you also receive exclusive benefits, like special opportunities to meet animals, discounts at Zoo stores and more.

Education Calendar

Find and register for free programs and webinars.

About the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

Why Do Wolves Howl? And Other Top Wolf Questions Answered

You asked the internet, we answered..

Today, we answer some of the most-searched questions about gray wolves, the largest members of the canine family!

Why do gray wolves howl at the moon?

We hate to burst your bubble, but it is a myth that wolves howl at the moon!

Howling may be heard at night, but it is not a behavior directed at the moon. Instead, it is used as a social rally call, a hail to hunt or as a territorial expression. Did you know that individuals have different howls that can be heard by other wolves 6-7 mile away?

A howl can even help a lost wolf find its way home. A wolf separated from its pack uses a “lonesome howl” — a shortened call that rises in pitch. If answered, the wolf then responds with deep, even howls to inform the pack of its location.

Do gray wolves hibernate?

No, gray wolves stay active throughout the winter. One of the few times they will seek shelter is to create maternity dens. These dens may be in rock crevices, hollow logs or overturned stumps, but most often are burrows dug by the parents.

Why do gray wolves travel in packs?

The gray wolf is one of the most social carnivores. A wolf pack typically has five to eight individuals, but as many as 36 have been reported in one pack. These family groups typically consist of an adult pair, called the alpha, and their offspring.

The alpha pair guides the group’s activity and takes control at critical times, such as during a hunt. A young wolf may venture out on its own, exploring the fringes of its territory before deciding whether to leave its parental pack behind.

How do gray wolves communicate?

In addition to howling, barking and growling, gray wolves use scent marking to maintain pack territories. Body language is also an important communication tool.

Dominant wolves may display raised hackles (the hair on the back of the neck), bared teeth, wrinkled foreheads and erect, forward-pointing ears. Conversely, a less dominant animal may lower its tail and body position, expose its throat, peel back its lips and fold back its ears.

Do gray wolves mate for life?

A wolf pack’s alpha pair is typically the only pair to breed and may mate for life.

Do gray wolves have predators?

Gray wolves once had one of the largest natural ranges of any terrestrial mammal in the Northern Hemisphere, but expansion into the western U.S. placed wolves and humans in conflict from the start. Cattle ranches believed wolves were a threat to their livelihood, and a history of hunting and poisoning devastated wolf populations, bringing them to the brink of extinction.

In 1973, the Endangered Species Act helped reestablish wolf populations. A combination of legal protection, human migration to more urban areas and land-use changes has helped stabilize them since, and in 1995, they were reintroduced to the northern Rocky Mountains.

How do gray wolves hunt?

Hunting in packs allows gray wolves to take down prey larger than themselves, including caribou, moose, deer and bison. They often hunt at night and will catch prey as a team or chase prey toward the remaining members of the pack as a trap.

What do gray wolves eat?

Gray wolves eat about 3-4 pounds of food per day. In addition to hunting large prey, they also catch beavers, rabbits and fish. They will even eat the occasional berry.

Visit American Trail to see the Smithsonian’s National Zoo’s gray wolves , Crystal and Coby.

Leaving the Pack

Every year, individual wolves across America leave the pack they were born into (called a “natal pack”) and go solo, becoming a “lone wolf” in the wild. While some may think it’s a brave choice—one reserved for the truly independent—a wild wolf’s decision to leave a pack and strike out alone is quite common. Known as “dispersing,” this is how wolves find mates and form new packs.

To understand why and when a wolf leaves its pack, it’s important to understand a few basics about pack dynamics in the wild.

All in the family

A wolf pack is essentially a family unit. There is a breeding pair (one male and one female) who are in charge. The rest of the pack is made up of their offspring—including new pups, yearlings and subadults. Occasionally, a dispersing wolf from another pack will join an existing pack. This most often occurs when either the breeding male or female dies, and a new partner is needed.

The family dynamic of a pack allows young wolves to learn how to survive in the wild from their parents and siblings. As part of a pack, wolves learn to hunt, avoid danger, and defend themselves.

A wolf pack can vary in size from only two breeding adults up to a multigenerational group containing 10 or more wolves.

As wolf pups age and grow, they venture farther and farther out from their den. By the time they reach six months of age, the young wolves are big enough to travel widely with their pack and assist with hunting elk and deer. By the time juvenile wolves reach 1.5 to 2 years of age they are fully grown and capable of hunting large prey on their own.

Should I stay or should I go?

Wolves reach breeding age at around age 2. Because there is usually only one breeding pair in each pack, a wolf at this age who is ready to find a mate must leave its natal pack.

The decision to leave, however, is not an easy one. Finding food without the help of a pack to hunt is challenging. There is no guarantee of finding a mate. And there’s safety in pack numbers.

“Until dispersal, a wolf lives its entire life in the pack’s territory,” says Colby Gardner, a wolf biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “This territory is all the wolf has ever known. Leaving a natal pack is much like leaving one’s hometown. It means venturing into new places, which brings new threats like roads, other packs and people.”

The life of a lone wolf is difficult and sometimes dangerous. Yet, the health of wild wolf populations depends on wolves dispersing, finding mates, starting new packs and spreading to new territories.

Looking for the one

While wolves have been documented dispersing throughout the year, fall and winter are the most common times for it to occur since breeding happens in the late winter.

Once a wolf disperses, it spends its days foraging for food and looking for a partner.

A primary method for finding a mate is through howling. Wolves can hear each other howl over distances of 6 miles in the wild depending on terrain.

Wolves also use their keen sense of smell to find a partner. The information a wolf can glean from a single sniff of another wolf’s urine or scat (poop) is truly amazing - they can learn the gender, diet, social rank, and breeding condition of another wolf by smell alone. Wolves can also tell how recently the scent was left, which helps them track each other across the landscape.

The distance a dispersing wolf must travel, and the time it takes for a wolf to find a new mate, vary greatly. It can be influenced by the number of dispersal-aged wolves in the area’s population.

For the lucky ones, they find a mate and form a new pack. It may take several years for a new pair of wolves to successfully reproduce in the wild. Once they do, their pack can continue to grow, and the cycle repeats itself.

Media Contacts

Related stories.

Latest Stories

You are exiting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service website

You are being directed to

We do not guarantee that the websites we link to comply with Section 508 (Accessibility Requirements) of the Rehabilitation Act. Links also do not constitute endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Log in/Log out (Opens in new window)

- All content

- Rural Alaska

- Crime & Courts

- Alaska Legislature

- ADN Politics Podcast

- National Opinions

- Letters to the Editor

- Nation/World

- Film and TV

- Outdoors/Adventure

- High School Sports

- UAA Athletics

- National Sports

- Food and Drink

- Visual Stories

- Alaska Journal of Commerce (Opens in new window)

- The Arctic Sounder

- The Bristol Bay Times

- Legal Notices (Opens in new window)

- Peak 2 Peak Events (Opens in new window)

- Educator of the Year (Opens in new window)

- Celebrating Nurses (Opens in new window)

- Top 40 Under 40 (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Spelling Bee (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Craft Brew Festival

- Best of Alaska

- Spring Career Fair (Opens in new window)

- Achievement in Business

- Youth Summit Awards

- Lynyrd Skynyrd Ticket Giveaway

- Teacher of the Month

- 2024 Alaska Summer Camps Guide (Opens in new window)

- 2024 Graduation (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Visitors Guide 2024 (Opens in new window)

- 2023 Best of Alaska (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Health Care (Opens in new window)

- Merry Merchant Munch (Opens in new window)

- On the Move AK (Opens in new window)

- Senior Living in Alaska (Opens in new window)

- Youth Summit Awards (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Visitors Guide

- ADN Store (Opens in new window)

- Classifieds (Opens in new window)

- Jobs (Opens in new window)

- Place an Ad (Opens in new window)

- Customer Service

- Sponsored Content

Why do wolves hunt in packs? The answer might be ravens

A raven moves on from a frosted spruce tree Jan. 5 in Turnagain. (Erik Hill / ADN archive 2017)

People who study animal behavior think they may have found out why wolves hunt in packs: Because ravens are such good scavengers.

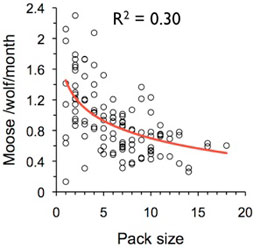

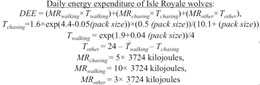

Scientists who watched wolves on Isle Royale in Lake Superior came up with the raven-wolf pack theory after puzzling over a question: Why do wolves hunt in large groups when a single wolf can take down a moose?

To find a possible answer, John Vucetich and Rolf Peterson of Michigan Tech and Thomas Waite of Ohio State University examined 27 years of wolf observations on Isle Royale in northern Michigan. Isle Royale, 45 miles long and up to 9 miles wide, sits in the northwest lobe of Lake Superior. A national park, the island supports a population of a few dozen wolves and hundreds of moose. Peterson studied the wolves for more than 30 years, and the researchers used observations from Peterson and his coworkers in the present study.

Peterson's team witnessed a single wolf killing a moose 11 times, which weakened the notion that wolves hunt in packs because of the difficulty of killing a moose without help. Vucetich, Peterson and Waite used the years of data from the Isle Royale wolf study to calculate that — in terms of energy burned and meat gained — wolves would do best hunting in pairs.

A wolf just east of Stony Creek in Denali National Park in 2013. (Jay Elhard / National Park Service)

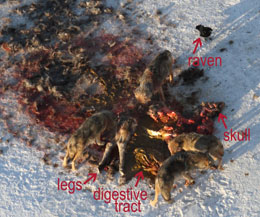

A 1,000-pound moose is much more than two wolves can eat right away, and that's where the ravens come in. In a study published in Animal Behaviour, the scientists detailed these facts about ravens found by other scientists: Individual ravens can eat and carry away up to 4 pounds of food per day from a large carcass. Ravens were responsible for moving half of a 660-pound moose carcass from a kill site in the Yukon Territory.

During the 27 years of Peterson's wolf observations used in the recent study, ravens were present at every wolf kill, often within 60 seconds of a moose's death. Noted raven researcher Bernd Heinrich has suggested that ravens evolved with wolves, with ravens possibly leading wolves to moose or caribou, and then later feeding upon the carcasses torn open by wolves.

That the wolf pack exists because of ravens is a new idea, supported by the group's "conservative assumption" that wolves lose up to 44 pounds of food per day to ravens while feeding upon a carcass, and that a pair of wolves loses about 37 percent of a moose carcass to ravens while a pack of six wolves loses just 17 percent.

Ravens sneak in to eat or carry away scraps of moose flesh and organs while wolves are feeding or resting away from the carcass, and the more ravens there are (researchers have counted up to 100 near kill sites), the harder it is for wolves to chase them off.

The urge not to die by starvation may drive wolves to kill "approximately twice as many large prey as would be needed in the absence of ravens," the scientists wrote. They also wrote that 85 to 90 percent of carnivore species hunt alone, and the wolf pack might not exist if not for the pesky, bold raven.

Ned Rozell | Alaska Science

Ned Rozell is a science writer with the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- The Inventory

Why everything you know about wolf packs is wrong

The alpha wolf is a figure that looms large in our imagination. The notion of a supreme pack leader who fought his way to dominance and reigns superior to the other wolves in his pack informs both our fiction and is how many people understand wolf behavior. But the alpha wolf doesn't exist—at least not in the wild.

Related Content

Top Photo by Caninest

Although the notions of "alpha wolf" and "alpha dog" seem thoroughly ingrained in our language, the idea of the alpha comes from Rudolph Schenkel, an animal behaviorist who, in 1947, published the then-groundbreaking paper "Expressions Studies on Wolves." During the 1930s and 1940s, Schenkel studied captive wolves in Switzerland's Zoo Basel, attempting to identify a "sociology of the wolf."

In his research, Schenkel identified two primary wolves in a pack: a male "lead wolf" and a female "bitch." He described them as "first in the pack group." He also noted "violent rivalries" between individual members of the packs:

A bitch and a dog as top animals carry through their rank order and as single individuals of the society, they form a pair. Between them there is no question of status and argument concerning rank, even though small fictions of another type (jealousy) are not uncommon. By incessant control and repression of all types of competition (within the same sex), both of these "α animals" defend their social position.

Thus, the alpha wolf was born. Throughout his paper, Schenkel also draws frequent parallels between wolves and domestic dogs, often following his conclusions with anecdotes about our household canines. The implication is clear: wolves live in packs in which individual members vie for dominance and dogs, their domestic brethren, must be very similar indeed.

A key problem with Schenkel's wolf studies is that, while they represented the first close study of wolves, they didn't involve any study of wolves in the wild. Schenkel studied two packs of wolves living in captivity, but his studies remained the primary resource on wolf behavior for decades. Later researchers, would perform their own studies on captive wolves, and published similar findings on dominance-subordinant and leader-follower relationships within captive wolf packs. And the notion of the "alpha wolf" was reinforced, in large part, by wildlife biologist L. David Mech 's 1970 book The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species (I'm linking it here, but please note that while the book has historical interest, some of its research is outmoded).

Mech spent several years during the 1960s studying wolves in Michigan's Isle Royale National Park as part of his PhD thesis work. Mech's book echoed Schenkel's notions of "alpha wolves" and competition-based pack hierarchies. Readers of Mech's book were led to believe that dominance played a key role in the lupine social order, and that wolves were naturally inclined to dominate one another. And Mech's book became a hit; it was republished in paperback in 1981 and remains in print (much to Mech's chagrin) to this day. It popularized a lot of our modern ideas about wolves, including competition-based hierarchies. Although Mech has since renounced the notion of the "alpha wolf," he admits that if you've heard the term, it's likely thanks to his book.

In more recent years, animal behaviorists, including Mech, have spent more and more time studying wolves in the wild, and the behaviors they have observed has been different from those observed by Schenkel and other watchers of zoo-bound wolves. In 1999, Mech's paper "Alpha Status, Dominance, and Division of Labor in Wolf Packs" was published in the Canadian Journal of Zoology. The paper is considered by many to be a turning point in understanding the structure of wolf packs.

Photo by Mats Lindh

"The concept of the alpha wolf as a "top dog" ruling a group of similar-aged compatriots," Mech writes in the 1999 paper, "is particularly misleading." Mech notes that earlier papers, such as M.W. Fox's "Socio-ecological implications of individual differences in wolf litters: a developmental and evolutionary perspective," published in Behaviour in 1971, examined the potential of individual cubs to become alphas, implying that the wolves would someday live in packs in which some would become alphas and others would be subordinate pack members. However, Mech explains, his studies of wild wolves have found that wolves live in families: two parents along with their younger cubs. Wolves do not have an innate sense of rank; they are not born leaders or born followers. The "alphas" are simply what we would call in any other social group "parents." The offspring follow the parents as naturally as they would in any other species. No one has "won" a role as leader of the pack; the parents may assert dominance over the offspring by virtue of being the parents.

While the captive wolf studies saw unrelated adults living together in captivity, related, rather than unrelated, wolves travel together in the wild. Younger wolves do not overthrow the "alpha" to become the leader of the pack; as wolf pups grow older, they are dispersed from their parents' packs, pair off with other dispersed wolves, have pups, and thus form packs of their owns.

This doesn't mean that wolves don't display social dominance, however. When a recent piece purporting to dispel the "myth" of canine dominance appeared on Psychology Today, ethologist Marc Bekoff quickly stepped in . Wolves (and other animals, including humans), display social dominance, he notes; it just isn't always easy to boil dominant behavior down to simple explanations. Dominant behavior and dominance relationships can be highly situational, and can vary greatly from individual to individual even within the same species. It's not the entire concept of wolves displaying social dominance that was dispelled, just the simple hierarchical pack structure. In response to the same piece, Mech pointed to a 2010 article he published detailing his observance of an adult gray wolf repeatedly pinning and straddling a male pack mate over the course of six and a half minutes. "We interpreted this behavior as an extreme example of an adult wolf harassing a maturing offspring, perhaps in prelude to the offspring's dispersal."

As research on wolves, both captive and wild, continues, we develop a more complex, nuanced picture of wolf behavior. But the easy notion of the "alpha wolf" still persists. Certainly in entertainment it has made for some nice stories; plenty of books and movies center around the notion of wolf—and werewolf—ranks. However, the outmoded idea of the "alpha wolf" still has some legs in a real-world area: dog training.

Just as, more than six decades ago, Schenkel extrapolated his wolf studies and applied them to domestic dogs, so too have many carried the notion of the "alpha wolf" over to dog training. Certainly, just as parent wolves hold dominance over their cubs and human parents hold dominance over their children, owners hold dominance over their dogs. Until my pup gets himself a credit card and a pair of opposable thumbs (and stops dissolving into delighted wiggles every time I tell him what a good little man he is), I'm pretty much the boss in our relationship. But some trainers take the idea of pack rank to the extreme; dog owners are given a laundry list of rules of how to maintain alpha status in all aspects of their relationship: Don't let your dog walk through the door before you do. Don't let her win a game of tug. Don't let him eat before you do. Some (famous) trainers even encourage acts of physical dominance that can be dangerous for lay people to execute. Much of this is a legacy of those old wolf studies, suggesting that we're in constant competition with our dogs for that pack leader position.

But, you might ask, mightn't domestic dogs behave much like wolves in captivity? Despite being members of the same species, wolves (even human-reared wolves) are behaviorally distinct from domestic dogs, especially when it comes to human beings. Take the famous experiment in which human-socialized wolves and domestic dogs are both presented with a cage with food inside. The food is placed inside a cage in a way that makes it impossible for either wolf or dog to retrieve it. The wolves will inevitably keep working at the cage, trying to puzzle out a way to remove the food. The dogs, after a few seconds of struggle, will look to a human as if to say, "Hey, buddy, a little help here?" Even if the hierarchical ranks were some innate part of lupine psychology, dogs have behaviors all their own.

Canine ethology is actually a very rich area of study. Researchers like Karen B. London and Alexandra Horowitz constantly contribute to our understanding of the domestic dog, and researchers like Mech (who has an updated book, Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation ) continue to expand our knowledge of wild wolves. And perhaps someday, our popular culture will more closely resemble our modern behavioral science rather than the results of outdated research.

- Project Overview

- All About Moose

- All About Wolves

- Annual Reports

- Art & Books

- Media Coverage

- Population Dynamics

- Earn Credit

- Publications

- Data & Interpretation

- Sonification

- College Students

- Join a Moosewatch Expedition

Ravens Give Wolves a Reason to Live in Packs

Why do wolves live in packs? Most predators are like tigers, leopards, and weasels - they live solitary lives. Think about Kipling’s Sher Khan and expressions like lone wolves. Predators are the very symbols of solitariness. But wolves are different. They live in groups, called packs, comprised typically of 4 to 12 wolves.

Assessing this idea, would require accounting for how all the costs and benefits of foraging change with pack size.

After a great deal of calculating and figuring, it seems that ravens offer wolves a reason to live in packs. It’s not what wolves kill that matters, but what they eat. Wolves living in larger packs lose less of what they kill to scavengers.

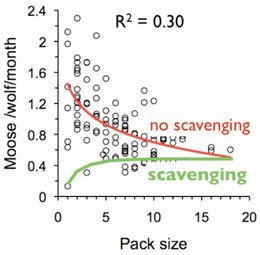

The red line is what wolves kill on a per wolf basis. The green line represents what each wolf get to eat (net energy gain, actually) when losses to ravens are taken into account.

When you catch something big, you must be prepared to deal with scavengers. Some species, like cougars, lions, and cheetahs hide the carcasses of their prey or cache them out of reach from scavengers.

Wolves have a different strategy. They eat fast. The faster a carcass is consumed, the less that is given to ravens. Wolves have two adaptations for fast eating.

First, wolves can consume a tremendous amount of food at one feeding. In just a couple of hours a large wolf can consume as much as nine kilograms (twenty pounds) of meat. This is why mothers invoke the wolf when asking their children to eat more slowly.

Second, wolves live in groups. The primary cost of group living is sharing food with pack mates. However, that loss is more than compensated by consuming food before ravens get it. Wolves that eat small prey are less vulnerable to scavengers, and are typically much less social.

So, is it important?

Science is important for discoveries that help us manage and control nature. However, discoveries like these about wolves and ravens, are valuable for a different reason. They reveal unexpected connections in nature. Awareness of such connections can inspire respect and wonder for nature. The importance of valuing nature in this way is under-appreciated.

- Discoveries

- Winter Study

News & Events

- 2023-2024 Annual Report

- Bones and Backpacks

- 2022-2023 Annual Report

- EMAIL SIGNUP

- PHOTO PERMISSIONS

Institutional Support for the Wolf-Moose Project:

Website Design and Construction by Monte Consulting .

How Wolves Are Driving Down Mountain Lion Populations

A recent study from Wyoming shows that when the two predators overlap, wolves kill kittens in high numbers and push adults to starvation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rasha.png)

Rasha Aridi

Daily Correspondent

:focal(982x617:983x618)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/e8/dbe806eb-81ca-489f-8106-93f0f9f05e51/gettyimages-1143011878_web.jpg)

The Lava Mountain Wolf Pack, the most populous of its kind in the American West, moved into carnivore biologist Mark Elbroch's study site in Wyoming's Teton Range in 2014. Various wolf packs took up residence in the nearly 900-square-mile area over the years, and this pack settled atop a massive, rocky cliffside. At the base of the cliffs lived a mountain lion named F47 and her three kittens.

Over the course of three months, the wolves killed off F47's kittens—one each month. Three other kittens in the study site also fell prey to the pack. Elbroch, the director of Panthera's Puma Program, didn’t see wolves attack the young cats with his own eyes, but he saw the aftermath: Bloodied bits of dismembered kittens strewn across the ground. "It was hard for us to watch," he says.

In the mid-1900s, scientists started trying to understand how North America's carnivores, like wolves and mountain lions, interact. Previous studies suggested that in places where mountain lions and wolves compete, wolves usually come out on top by stealing the lions' kills or changing where the cats hunt. But wildlife biologists weren't sure just how detrimental wolves could be to mountain lion populations. A study published in November in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B provided the first evidence that when the two species overlap, wolves have a greater effect on mountain lion populations than hunting by humans and the availability of prey. And the ways scientists say that wolves impact populations? By starving out adults and killing kittens.

In 1995, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and biologists from Yellowstone National Park reintroduced gray wolves to the park after they were killed off from the region in the 1920s. The reintroduction created an invaluable opportunity for biologists to study how wolves shape their environment. Nearby, in the Grand Tetons, scientists established a study site in 2000 to monitor what ecological changes stemmed from the wolves’ return, and various teams from conservation organizations, universities and state and federal agencies used the locale to untangle how wolves interact with other species.

In an earlier study, Elbroch and his team reported that over the course of 15 years, the mountain lion population in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem in Wyoming dropped by 48 percent . They considered three main theories for the decline: human hunting of cats, a lack of prey or the presence of wolves.

To figure out what exactly cut the mountain lion population nearly in half, Elbroch and his team analyzed data gathered on 147 mountain lions living in the study site. During those years they tracked down cats and kittens and equipped them with telemetry or GPS collars that reported the predators’ locations. Not only did the collars provide Elbroch with an understanding of how the cats moved through the landscape, but they also helped the team locate mountain lions after they died—which allowed the researchers to determine how a cat met its demise. They then plugged that data, along with data on elk and wolves, into a population model to reveal patterns in the relationships between the three species.

The model was able to determine the strongest drivers of the declining mountain lion population during the study period, as well as forecast how the cats would fare in the future. Elbroch found the growing population of wolves was the culprit behind the massive decline.

Elbroch suspects that the drastic drop was largely due to wolves affecting the cats’ access to prey, namely elk. In a wolf-less study site, elk herds resided in the comfort of the mountains; when the wolves moved in, the herds started congregating in large groups in the open grasslands to protect themselves from a pack attack. Since mountain lions stealthily stalk and ambush their prey under the cover of brush, they couldn't reach the elk in the grasslands, and starvation became a more common cause of death among the cats.

The kittens didn’t fare well, either. The model showed that over the 16 years, roughly a third of kittens at the site survived until they were six months old, and only around a quarter ever made it to their first birthday. "This is the lowest survival ever reported for kittens anywhere," Elbroch says. For the youngsters, the predominant cause of death was from brutal wolf attacks that could wipe out entire generations of kittens, like the Lava Mountain Pack did in 2014.

The most recent study’s findings revealed that the wolves' impact on mountain lion abundance is so strong that the yearly average mortality associated with human hunting is comparable to the effects of just 20 wolves. That finding is remarkable given that more than 90 wolves were once recorded living in the study site, which would have placed an enormous amount of pressure on the cats.

Elbroch was shocked at how wolf-related deaths completely eclipsed those from hunters. "The narrative for mountain lions for the last 50, 60 years has been that human hunting is the primary driver of population dynamics for mountain lions, and that is absolutely true—except where they overlap with wolves,” he says. “Now we're going to have to rewrite the whole narrative that rolls up the bigger impact on population dynamics for mountain lions, which has huge ramifications for their management."

While mountain lion populations have expanded across most of the American West, wolves are still trying to recolonize parts of their historic range. Since wolves affect mountain lion abundance so greatly, the study suggests that in places where wolves and mountain lions overlap, officials should implement more restrictive hunting quotas on cats to avoid a crash in their population.

Korinna Domingo, the founder and director of the Cougar Conservancy, who was not involved in this study, suggests that wildlife managers should pause mountain lion hunting or reduce the quota in areas where wolves are moving back into the ecosystem. Doing so will allow the cats to deal with one major threat at a time instead of trying to evade both hunters and wolves simultaneously. "That needs to be a very serious consideration," she says.

But such scientific recommendations aren't always implemented in practice because wildlife management decisions don’t just depend on the science, they also rest on public input. The major comebacks of wolves and mountain in recent decades have been met with backlash, Elbroch says. Hunters argue that carnivores prey on elk and deer, reducing the number that are around to hunt, and ranchers worry that carnivores will prey on their livestock. When wildlife biologists come up with plans to manage carnivores, they try to balance hunters' and ranchers' desires to kill them with what the science says.

"I can build a population model and really look at what's the best way to actually manage populations based [for] mountain lions, or wolves or deer populations," says Mark Hurley, a wildlife research manager for Idaho, who was not involved in the study. "But when it comes right down to it, sometimes that really doesn't matter because it's people's values [at play]."

Oftentimes, the demands of stakeholders outweigh what the science says, according to Elbroch. Agencies are managing for the constituents that want fewer—or no—carnivores on the landscape, he says.

Given that wolves are recolonizing their historic ranges across the American West and moving into mountain lion territory, states that do not already have wolf populations will soon be faced with the challenge of managing them. They'll also have to reevaluate how they manage mountain lions when the wolves take up residence.

"Wolves are now in Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana and moving outward still,” says Elbroch. “And these are all states that have aggressive mountain lion management. It will be fascinating to see how they decide to alter their management of mountain lions as wolves move into the system."

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rasha.png)

Rasha Aridi | | READ MORE

Rasha Aridi is a science journalist based in Richmond, Virginia. She has written for Science magazine and Science News for Students . You can find her portfolio at rashaaridi.com .

Norske og internasjonale forskningsnyheter

Forskningsnyheter for unge

Science news from Norway in English

Meninger, debatt og blogger skrevet av forskere

Forskning.nos stillingsmarked

You might be looking for...

Wolf packs don’t actually have alpha males and alpha females, the idea is based on a misunderstanding

The researcher who introduced this term tried to clear the confusion up two decades ago, but the myth still lives on..

You may have heard that a wolf pack is led by an alpha pair.

Given this designation, it’s easy to imagine that a pack consists of young adults and older animals in a strict ranking system. You can imagine that relatives, newcomers and challengers are all part of the system. Maybe some of these wolves might challenge the alpha male to take over leadership of the pack?

On the Howstuffworks website, for example, you can read that wolves follow "an incredibly sophisticated group hierarchy", and that wolves naturally organize themselves in packs for stability and to help each other with hunting.

The pack structure is said to include a "beta wolf" who is the deputy and the "omega wolf" who is at the bottom of the rank, and often the victim of bullying.

In reality, wolf packs are usually much less complicated.

Doesn’t work for wolves in the wild

Calling wolves alpha and beta animals comes from research on wolves in captivity, says Barbara Zimmermann.

Zimmermann is a professor at Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences who studies wolves.

“The leader is called the alpha male. Then there may be several rank levels, beta, gamma and so on. But this is not a concept that works for wolves in the wild,” she says.

Most wolf packs simply consist of two parents and their puppies. The group may also include one- to three-year-old offspring that have not yet headed out on their own.

“The adults are simply in charge because they are the parents of the rest of the pack members. We don’t talk about the alpha male, the alpha female and the beta child in a human family,” Zimmermann said.

Battle for leadership in captivity

So how did the idea for the alpha wolf come about?

Rudolf Schenkel wrote about social structure and body language among wolves in 1947.

Schenkel studied wolves at the Basel Zoo in Switzerland, where up to ten wolves were kept together in an area of 10 by 20 metres.

He saw that the highest ranked female and male formed a pair, and that the hierarchy could change.

"By continuously controlling and suppressing all types of competition within the same sex, both ‘alpha animals’ defend their social position,” Schenkel wrote.

According to another well-known wolf researcher, David Mech, it was Schenkel's work that gave rise to the idea of the alpha wolf, according to The International Wolf Center website.

As early as 1947, Schenkel mentioned that it was possible that wild wolf packs consisted of a monogamous pair, their puppies and one- to two-year-old pups. But this information was overlooked.

Rudolf Schenkel's work had great influence, said Ane Møller Gabrielsen, a senior research librarian at NTNU, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

In 2015, she completed her doctorate on “Power and meaning in the conflict zones over keeping dogs”. Her dissertation describes research on pack structure in wolves, and how it in turn affected views on dog training.

Pecking order

Another Norwegian, Thorleif Schjelderup-Ebbe, also contributed with important insights.

Schjelderup-Ebbe established the term "pecking order " in the 1920s to describe relationships among chickens. This describes how chickens can be aggressive towards birds below them in the social hierarchy, but not towards those above them.

“The concept of the pecking order became very popular. It had great influence on the whole view of science at that time, at least in research that had to do with living organisms. It was seen as an underlying dominance principle that structures society and behaviour,” Møller Gabrielsen said.

Popularized the alpha wolf concept

A great deal of research was done on the wolf's pack structure in the 1960s and 1970s, but this was mainly on wolves in captivity, Zimmermann said. For example, Erik Zimen, a Swede, worked with social organization among wolves in captivity.

These wolves were not necessarily related and were kept in an unnaturally small area.

In 1970, the book The Wolf: Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species was published, written by David Mech. It was a success. The book helped to popularize the alpha concept, because many people referred to Mech’s work.

Mech has written on his website that he repeatedly asked the publisher to stop printing the book because much of the information is outdated — including the concept behind the alpha wolf. Nevertheless, the book is still being sold.

“David Mech, the world's most profiled wolf researcher, used the terminology alpha animals in his early research. But by the time he realized that this was a mistake, the term had already taken root in the literature. He is now struggling to get this changed,” Zimmermann said.

Affected dog training

The alpha wolf theory was of great importance in dog training, says NTNU’s Ane Møller Gabrielsen.

“This was true especially after 1970, when David Mech published his study. In addition, you have a number of other well-known names who published research based on animals in zoos. This gave us a pretty clear picture of the wolf as a very authoritarian animal with an almost a military ranking,” she said.

Dog training comes from the military, Møller Gabrielsen said. The military used punishment as a training tool.

“Once the concept of the wolf and its strict hierarchy was established, trainers were more likely to use punishment. It wasn’t just that the dog was punished when it did something wrong, you had to show the dog that you were the alpha wolf all the time,” she said.

Some of the methods involved physical punishment, such as taking the puppy by the scruff of the neck and shaking it. These ideas became less widespread in the dog training literature throughout the 2000s.

“Most of what has been published in books since 2000 is so-called positive training, which is reward-based dog training that uses the least possible punishment and no physical punishment. So there has been a very big change,” Møller Gabrielsen said.

Close contact with wolves

In 1999 and 2000, David Mech published two articles in which he tried to correct the popular misunderstanding about how a wolf pack is organized.

By that time, Mech had studied wild wolf packs on Ellesmere Island in Canada for 13 summers. He was able to acclimatize one of the wolf packs to his presence. That allowed him to study the pack up close — up to one metre, over several years.

He wrote that what was commonly called the alpha pair was simply the parents of the rest of the pack. As parents, they consequently led the pack’s activities.

“Dominance fights with other wolves are rare, if they exist at all. During my 13 summers where I observed the pack, I saw none,” Mech wrote in an article entitled “Alpha Status, Dominance, and Division of Labor in Wolf Packs”.

The parents decide

The younger wolves were submissive to the parents. The parents controlled the distribution of food. The couple prioritized the youngest puppies to ensure they would get enough food if it needed to be shared. Older siblings may do the same thing, Mech wrote.

All the animals eat at the same time from a large carcass. But if the carcass is small, the parents eat first and determine when the pups are allowed to eat, he wrote.

However, there are also wolf packs that have a slightly different and exciting structure that we’ll come back to later.

Here’s how Norwegian packs are structured

Barbara Zimmermann at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences and her colleagues have studied pack cohesion in Norwegian wolves using GPS data. This has given them insights into how these wolves live together.

“A typical wolf pack in Scandinavia consists of six animals on average, most often the parents and four yearling puppies,” says Zimmermann.

A typical year for a Scandinavian wolf pack first involves a male and a female pair establishing a territory. They mark a large area in the forest with scent, which they patrol and defend against other wolves.

The wolves mate in February-March and the young are born in May, in a den.

While the female nurses the young, the male must hunt for the first few weeks.

“At this time, moose calves are small. The male wolf eats as much food as possible and comes back and vomits it up for the female to eat,” she said.

After a couple of weeks, the female also begins to take hunting trips while the male remains in the den.

- RELATED: Inbreeding in Scandinavian wolves is worse than we thought

Strong attachment

“What is exciting about wolf pairs is that they are unbelievably faithful. They stay together all the time,” Zimmermann said.

Wolves are monogamous, and usually do not change partners until one dies.

The denning period is mostly the only time when they hunt apart, Zimmermann said.

“More than 70 per cent of GPS positions from wolf pairs show they remain within 100 metres of each other. So they are incredibly dependent on each other,” she said.

After the denning period, the puppies are carried to a new location, which is usually by a carcass. Then the parents move in star shape around the area. After a few weeks, they are moved to a new location.

In September - October, the young are big enough to start following the adults. But even then they have a common location. The adults go out and hunt together in the evening. Then they go get the pups when they have killed their prey.

Quick to become independent

By November, the pups are so big that they start to wander a little farther away from their parents. But they stay within the territory.

“There may be individual pups that hang around on their own before they come back to the rest of the pack after two or three weeks,” Zimmermann said.

“There is a lot of dynamism from November onwards, where you see that the pups gradually become more and more independent,” she said.

Most puppies leave the pack when they are one year old. At this point they have grown to the point where they look like adults. They usually reach puberty their second winter, but this can be delayed if they have remained with their parents.

The first "wave" leaves the pack when the parents mate again, and the second group leaven when the parents have new pups.

At this point, the young wolves go out in search of a partner and a suitable area to establish their own territory.

Some young animals remain in their parents' territory for one to two more years.

Zimmermann describes an example from her GPS studies. This wolf did not leave the pack as a one-year-old, like its siblings did.

“We saw from the GPS data that it was constantly trying to get close to the adults that had new pups. Then it disappeared again, possibly it was chased away,” she said. “But in the autumn it returned to the pack and was with the adults and its new siblings all winter, until February-March,” she said.

It ended up that this particular wolf established a territory right next to its parents, where there was available space.

- RELATED: Wolves - whether to kill them or not, has been a hot topic for debate in Norway for years. Learn more in the story Political controversy over how Norway decides to shoot wolves

Hunting in packs?

The findings described above come from the report Ulvevalpers flokksamhold og områdebruk i Skandinavia (Wolf pups’ pack cohesion and areal use in Scandinavia).

The researchers wrote that the fact that the young gradually become more independent early on “stands in stark contrast to the perception that a pack of wolves is a close-knit unit that hunts in teams and moves together at all times."

Zimmermann notes that it’s usually only the parents that hunt.

“The pups are usually not involved. The pups are not good at hunting themselves either, so they are pampered by the adults,” she said.

As a result, the one-year-old pups aren’t necessarily that good at hunting before they head off on their own, she said.

“They probably learn a bit from watching their parents, and they may sometimes be on some hunts. But it seems like they are very bad at hunting when they leave the pack,” she said.

“We have some data on lone wolves and what they kill. It's not much. It's almost a surprise that they survive. But they are canines, they manage to survive on little food,” she said.

But in some places in America, things are a little different. Here you can see large packs of wolves hunting in teams.

Packs with many members

There are video recordings, particularly from Yellowstone National Park, of large packs hunting together, Zimmermann said. In this situation, the pack contains several one- to three-year-olds. Wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone in 1995.

“There are much higher prey densities and completely different conditions,” Zimmermann said. “The thing is that when the wolf density increases and there start to be a lot of packs in very small territories, you see that the packs get bigger.”

There it is more common for the pups to wait longer to go out on their own. The packs can thus consist of the parents and offspring from the last four years.

There have also been reports of cases from America where a wolf pair "adopts" a young male wolf that is unrelated, at least for a period. L. David Mech and Luigi Boitani wrote about this in their book Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. As a rule, these intruders are normally chased away or killed.

“We have no documented cases of this in Scandinavia. This is something that has been published from Yellowstone,” says Zimmermann.

Other variations that can be seen in wolf packs is when one of the parents dies and a new partner comes from outside, perhaps with cubs in tow. It has also been observed that a daughter can become a partner with her stepfather and take over for an ageing mother who remains in the pack.

In large packs, it can even happen that two bitches give birth to puppies, both mother and daughter.

The daughter is then still subordinate to the mother, but controls her own pups. In such relatively rare cases, it’s possible that you can more rightly call the original pair alphas, Mech wrote in his 1999 study.

“The point here is not so much the terminology, but what the terminology falsely implies: a strictly strength-based dominance hierarchy,” he wrote.

Packs with two mothers can later be split in two, if the daughter, for example, has mated with an adoptive male.

Takes time to change

The term alpha wolf is not widely used by wolf researchers today. But it is still well established in our consciousness, Zimmermann said. In the middle of a sentence, she corrects herself.

“Alpha animals ... I mean the leader animals or the adults,” she said. “As you can see, it's still in there. But that’s completely wrong.”

In an article from 2008, David Mech wrote that it is said that it takes 20 years before new research fully sinks in. Perhaps this is also true for the concept of the alpha wolf.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no.

References:

Kristoffer Nordli , Barbara Zimmermann, Petter Wabakken, Ane Eriksen, David Carricondo-Sanchez, Erling Maartmann, Håkan Sand & Camilla Wikenros: “ Ulvevalpers flokksamhold og områdebruk i Skandinavia ” (Wolf pups’ pack relationships and areal use in Scandinavia) Høgskolen i Innlandet, 2019.

Ane Møller Gabrielsen: “ Makt og mening i hundeholdets konfliktsoner ” (Power and meaning in the conflict zones over keeping dogs), PhD dissertation, NTNU, 2015.

Rudolph Schenkel: Expression Studies on Wolves, 1947. Available here.

L. David Mech: “ Alpha Status, Dominance, and Division of Labor in Wolf Packs ”, Canadian Journal of Zoology, 1 November 1999. Summary.

L. David Mech: “ Leadership in Wolf, Canis lupus, Packs ”, Canadian Field Naturalist , 2000.

L. David Mech and Luigi Boitani (Eds.): “Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation”, 2003. Excerpt available here.

L. David Mech: “ Whatever Happened to the Term Alpha Wolf? ”, International Wolf, winter 2008, International Wolf Center.

Political controversy over how Norway decides to shoot wolves

What kind of person supports illegal hunting of Norway’s wolves?

Leif and Anette Marie were the first to lose their lives in the World War II in Norway

MRSA bacteria: The Sneaky and Sometimes Dangerous Tenant in Your Throat

While her husband was doing forced labour for embezzlement, Maren Bang wrote the first Norwegian cookbook

God originally had a wife

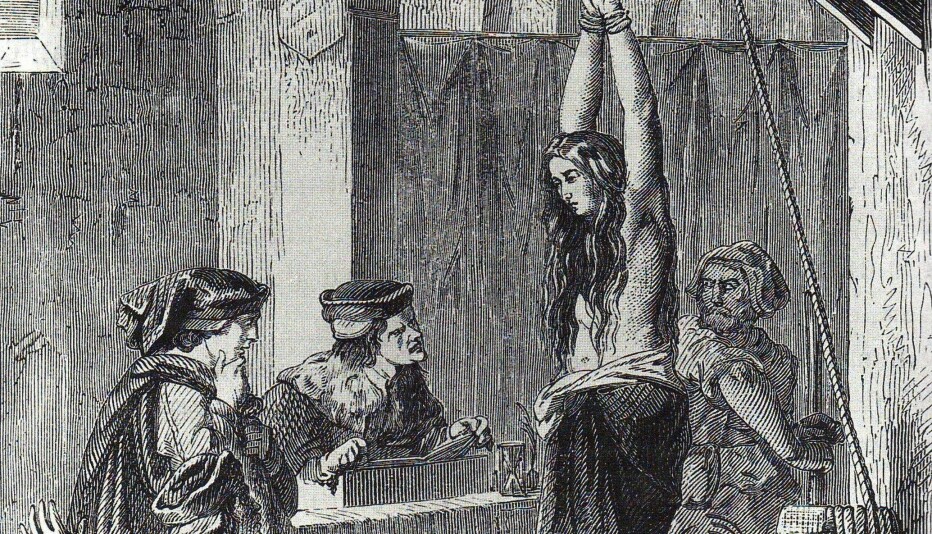

The judge who saved witches from the stake

Prison officer so irritated by researchers with no experience that he pursued a doctorate himself

All sperm whales off the Norwegian coasts are males. Their lives are far more interesting than we imagined

“Our urine is worth its weight in gold,” says researcher

New discovery: Cod can adjust to climate change – from one generation to the next

Artificial intelligence makes smarter use of seaweed and kelp

The end of witch trials did not stop religious persectuion of Norway's indigenous Sámi people

Researchers are testing a new product to relieve dry mouth

Knitting came back, but not hairpin lace. Why?

What exactly is Down syndrome? Marte wishes people knew more

What is it like to learn Norwegian?

What is happening to the Arctic sea ice in winter?

Do we care that red meat is bad for the climate, or do we just eat what we want?

The Earth traps more heat than before. This is partly due to cleaner air

Is there something wrong with the prisons in Norway?

Harmful substances have been found in plastic food packaging – but do we ingest them?

Women who have been in prison face a much higher risk of early death

Is it possible to make healthy french fries?

"There are few who drink such large amounts of coffee"New study raises the alarm on energy drinks and sleep

Does social media content creation impact the professional identity of preventive health professionals?

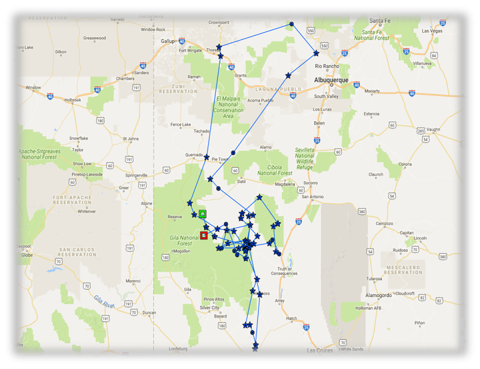

Two Mexican gray wolves are released in southern Arizona's Sky Islands. Why that matters

Two endangered Mexican gray wolves were released in the Peloncillo Mountains of southern Arizona as wildlife managers try to expand the range of the predators.

The two wolves, officially known as F1828 and M2774, would become the first pack to roam Arizona's Sky Islands in decades and the southernmost wolf pack in the U.S.

“The hope is that as populations continue to expand in numbers, they will continue to expand southward and eventually meet up with this pair of wolves or some of their progeny,” said Jim deVos, the Mexican wolf coordinator for the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

The wolves, named Llave and Wonder by advocates, were removed from the wild in 2023 and paired in captivity over the winter. Before releasing Llave, wildlife managers confirmed she is pregnant.

State and federal wildlife agencies previously released family packs to establish a wild population. Now that the wolves' numbers are growing , adult releases have become more uncommon, as the wolf recovery program focuses on fostering genetically valuable captive-born pups into wild dens.

Wildlife advocates praised agencies for this release and said they'd like the agencies to authorize more in the future.

“Restoring these wolves to the wild is definitely worth celebrating,” said Chris Smith, southwest wildlife advocate for Wild Earth Guardians.

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would do well to release more bonded family packs of endangered lobos in the Southwest to help ease the genetic crisis this species is facing,” he said.

100 foster pups: Mexican gray wolf packs grow with captive-born pups. Will it help the species survive?

Wolves return to the Sky Islands

Llave and Wonder were born in Arizona within the Mexican Wolf Experimental Population Area.

Llave was captured and relocated to Mexico in 2022 when she reached breeding age. She found a mate, M1582, and the pair wandered back over the U.S. border, setting up a territory in the Peloncillo Mountains.

“The fact that she was able to connect the Mexican and United States wolf populations is really rare,” Smith said.

After her mate was killed in 2023, Llave roamed on her own.

She likely sought a new mate in territory unoccupied by other wolves, who primarily live farther north. Lone wolves isolated from the primary population do not contribute to Mexican wolf recovery, unable to find mates and produce offspring.

Wildlife managers recaptured her and paired her with Wonder, hoping they would breed. The two spent the winter in captivity at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico.

“We’re at least giving her a chance to play a role in recovery by pairing her with an available male,” deVos said.

Both wolves wear satellite collars to monitor their movements around the Sky Islands and watch for denning activity, which usually occurs when the wolves become localized in one area during the spring.

“It’s important that they are close to the Mexican border because part of the long-term plan is to have the exchange of wolves from north to south and south to north across international boundaries,” deVos said.

Mexico started reintroducing wolves in 2011, and according to the 2022 revised Mexican wolf recovery plan, about 31 wolves were living in Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico, in 2017.

Although advocates believe few wild wolves remain in Mexico, officials hope that as the populations grow and disperse, individuals can more easily move and exchange genetics.

Mexican gray wolves: Asha, the adventurous wolf, is recaptured, paired with a male to mate

Fostering vs adult releases

Smith believes Llave’s international journey in and out of captivity is representative of the challenges Mexican wolf recovery faces.

“This confluence of factors tell the challenges of Mexican wolf recovery,” Smith said. “The failure of the Mexico program, the impacts that Trump's border wall has on the population as a whole, possible illegal killings. Her resilience and the fact that the feds did the right thing is worth celebrating.”

Smith and wolf advocates want the state and federal wildlife agencies to release more family packs, believing those releases are more effective in diversifying the wild population’s gene pool.

“If you picked any two wild wolves at random and did a genetic test on them, they would likely be, on average, as related as siblings,” Smith said.

Wild Mexican wolf pups have a 50% chance to live to their first year, and 70% of yearlings survive to breeding age at two years old, according to USFWS. Smith believes older wolves have a better chance of living in the wild and disseminating their genes.

Llave’s release was a special case and does not signal a return to more pack releases, according to AZGFD.

deVos says there is a geographical benefit to fostering wolf pups instead of family units. By splitting a litter of genetically valuable foster pups between multiple wild dens, deVos believes their genes will be spread more widely in a shorter period.

Wolves tend to stay with their natal packs until they reach breeding age, before wandering to mate and start a new pack.

“We’re geographically spreading that genetic material, rather than having all of those pups in one single pack in a single area,” deVos said.

Hayleigh Evans covers environmental issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Send tips or questions to [email protected] .

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust .

Sign up for AZ Climate , our weekly environment newsletter, and follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook , X and Instagram .

You can support environmental journalism in Arizona by subscribing to azcentral today .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Wolf Ecology Basics. Wolf groups, or packs, usually include dominant male and female parents (breeding pair), their offspring, and other non-breeding adults. Wolves begin mating when they are 2 to 3 years old, sometimes establishing lifelong mates. In some larger packs, more than one adult female may breed and produce pups.

The wolf pack, led by the alpha female, travel single-file through the deep snow to save energy. ... The wolf packs in this National Park are the only wolves in the world that specialize in ...

All species and subspecies of wolves are social animals that live and hunt in families called packs, although adult wolves can and do survive alone. Most wolves hold territories, and all communicate through body language, vocalization and scent marking. ... Wolves will travel for long distances by trotting at about five miles per hour. They can ...

Wolves hunt and travel in packs. Packs don't consist of many members, though. Usually, a pack will have only one male and female and their young. This usually means about 10 wolves per pack ...