UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

- All Regions

- Measuring Employment in the Tourism Industries – Guide with Best Practices

This guide provides some examples of best practices of measuring employment in the tourism industries from countries that have demonstrated capacity to develop a comprehensive set of employment indicators.

This publication is a joint project by the International Labour Organization ( ILO ) and UNWTO.

ISBN : 978-92-844-1615-8

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Related Content

Un tourism news 82: sustainable development of tourism, am news | vol. 63 april 2024, un tourism news 81: global tourism investments trends a..., un tourism news 80: diversification, innovation and sus....

The role of the tourism sector in creating direct employment in Mexico: evidence from linear and nonlinear ARDL frameworks

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 23 November 2023

- Volume 3 , article number 213 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Fernando Sánchez López ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2504-0407 1

921 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper analyzes the role of the tourism sector in creating direct employment in Mexico by measuring the output elasticity of tourism employment from both linear and nonlinear perspectives. Although using such elasticity is a common practice for calculating the impact of economic growth on employment, it has been neglected in the context of the tourism labor market. Using Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) and Nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) models, this study analyzes the impact of both the quarterly indicator of tourism gross domestic product (GDP) and the multilateral real exchange rate on tourism employment from the first quarter of 2006 to the first quarter of 2021. The results of the linear models show that tourism employment is elastic to variations in tourism GDP. Conversely, the NARDL model illustrates that tourism employment is inelastic to both positive and negative changes in tourism GDP. However, the NARDL model also shows that tourism employment is resilient to the negative phases of growth in the sector, as it grows more during the expansive episodes than it is reduced during the contractive phases. Meanwhile, the models including the multilateral real exchange rate show that tourism employment positively responds to the depreciation of the Mexican peso.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of TV series on tourism performance: the case of Game of Thrones

Information and Communication Technology (ICT), Growth and Development in Developing Regions: Evidence from a Comparative Analysis and a New Approach

The relationship between CO2 emissions, economic growth, available energy, and employment in SEE countries

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Creating adequate conditions to stimulate economic growth is a major objective of economic policies as economic growth is related to employment expansion; however, the intensity of this relationship varies across countries and periods (Herman 2011 ) as it depends on the following factors: law, preferences, technology, social customs, and demographics (Neely 2010 ). Moreover, the relationship between unemployment and economic growth, as studied by Okun ( 1962 ), is now considered a statistical connection, rather than a structural feature of an economy, as it changes not only over time but also over business cycles (Knotek 2007 ).

Tourism has become one of the main economic activities, particularly in developing nations, as it helps poor areas escape poverty by promoting regional development (Yang et al. 2021 ), generating additional livelihood options, and boosting economic growth (Hipsher 2017a ). Additionally, tourism contributes to poverty alleviation by creating employment opportunities for people with low levels of skill and education (Hipsher 2017b ; Weinz and Servoz 2011 ). Apart from collaborating through the creation of inclusive employment, it provides jobs for women, young people, and marginalized groups, such as tribal or indigenous people (Hartrich and Martínez 2020 ), while generating numerous indirect jobs (Dahdá 2003 ).

Traditionally, the tourism sector’s capacity to create employment has been considered a direct function of the number of tourists (Walmsley 2017 ). However, Santos ( 2023 ) found that in the specific case of Northern Portugal, inbound tourists had a negative, although statistically insignificant, impact on employment creation.

The main objective of this study is to estimate the output elasticity of tourism employment from both linear and nonlinear perspectives. To achieve this objective, the quantitative analysis was performed using linear and nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag models, abbreviated as ARDL and NARDL, respectively. This study was carried out under the hypothesis that tourism, besides boosting job creation, is resilient to negative changes in tourism GDP.

I believe that this study will be of interest for both tourism researchers and policymakers as, although estimating the output elasticity of employment is a common practice among economists, to the best of my knowledge, this is the first time that it has been calculated for the tourism sector, either in its linear or nonlinear form. Similarly, I have not found any study analyzing the impact of the real exchange rate on tourism employment.

The results of this study show that, when using the linear model, tourism employment is elastic to changes in tourism GDP, but inelastic to changes in the real exchange rate. Conversely, the NARDL model illustrates that tourism employment is inelastic for both positive and negative variations in tourism GDP; additionally, the effect of the real exchange rate becomes shorter. In this sense, this article contributes to the existing literature not only by providing evidence of tourism as an important generator of direct employment but also by showing that tourism employment is resilient to contractive episodes in tourism GDP. Additionally, it collaborates by exhibiting the inelastic positive effect of the real exchange rate on the creation of tourism employment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The second section is divided into two subsections, with the first subsection presenting a literature review related to the relationship between tourism and employment creation, and the second subsection presenting a review of the impact of tourism GDP and the real exchange rate on tourism employment. The third section is also divided into two subsections; the first presents the study materials and their sources and the second presents the ARDL and NARDL empirical designs. In the fourth section, I present the econometric results. Finally, the discussion and conclusions are presented.

Literature review

Tourism and employment.

Services are considered to have a positive impact on job creation and are regarded as employment-intensive activities (Basnett and Sen 2013 ; Ghose 2015 ). Services have become the most important sector in terms of their contribution to GDP and employment creation (Gurrieri et al. 2014 ). While tourism is connected to a vast number of economic branches, it is especially associated with numerous activities in the service sector, sometimes called “tourism services” (Álvarez 1996 ). Several studies have documented the relationship between tourism and employment generation, pointing out that tourism is an employment-intensive sector (Bhattarai et al. 2021 ; Bote 1990 ) and a booster of inclusive growth (Prasad and Kulshrestha 2015 ).

According to Walmsley ( 2017 ), the total demand for tourism employment can theoretically be regarded as a function, although not necessarily linear, of the number of tourists under the assumption that there is a positive relationship between these two variables. In other words, if the number of tourists increases, so does the total demand for tourism employment. According to the same author, there are three possible ways in which employers can increase their tourism workforce, namely, recruiting more staff, increasing the productivity of current staff, or a combination of both.

According to Tribe ( 2011 ), employment in the tourism and leisure sector is determined by the demand for tourism goods and services, meaning that this type of employment is directly related to tourist expenditure. However, tourists also spend money on imported goods and services, thus creating employment abroad. Additionally, as noted by Stabler et al. ( 2009 ), the consumption of both international and domestic tourists can include products or services that are not specifically designed for tourists. As per Tribe ( 2011 ), the number of jobs created by the tourism sector also depends on the relative price of labor and the technical mix of factors influencing the provision of goods or services. Effectively, following Varian ( 1992 ), the technical mix of factors would indicate, according to the technique utilized by a company, the number of labor units required to produce one unit of a certain good.

However, a company’s main objective is to maximize its benefits, and the maximum benefit is attained when costs are minimized (Varian 1999 ). By this logic, employees are perceived as a cost to be minimized (Walmsley 2017 ), implying that firms are unlikely to fulfill their need to adapt their production capacity by merely hiring more people as this is an expensive and time-consuming process (Burggraeve et al. 2015 ; Walmsley 2017 ). Instead, when responding to a variation in the level of production activity, companies usually first modify their intensive production margin, and recruit more employees only when all the tools that make employment more flexible have already been used and increases in demand have been made certain (Burggraeve et al. 2015 ).

As tourism demand is influenced by seasonality, this phenomenon also affects tourism employment. During the negative phase of the tourism seasonal cycle, which is characterized by medium and low seasons, tourism companies seek strategies that allow them a certain margin of operability and profitability (Ramírez 1994 ). Consequently, tourism companies tend to have permanent staff and hire temporary employees as needed to achieve an adequate level of efficiency and quality of service provision (Caballero 2011 ). Young workers occupy a considerable number of temporary positions in the tourism sector, and temporary contracts are usually terminated once the seasonal peak ends (Jolliffe and Farnsworth 2003 ). However, seasonality does not have the same impact on all tourism subsectors; for example, seasonality is stronger in lodging than in restaurant services (Bote 1990 ).

It is important, however, to consider that tourism has been extensively criticized for creating precarious employment as most tourism workers are paid less than the “all-industry average” (Robinson et al. 2019 ). Additionally, most of the precarious positions are occupied by young people, women, and migrant workers (Ioannides et al. 2021 ). In fact, a large part of tourism activities is carried out by women who are usually employed in vulnerable and low-paid positions; besides that, an important part of the tourism workforce is made up of minors and students (Domínguez et al. 2021 ).

Finally, other significant factors affecting tourism demand include artificial and natural disasters, publicity, income level, local prices, and competitors’ prices (Panosso and Lohmann 2012 ). The COVID-19 outbreak, which was officially declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO 2020 ), had a profoundly negative impact on the number of tourist arrivals internationally as a result of the contingency strategies adopted by different nations, such as quarantines and community lockdowns (Sigala 2020 ).

Economic growth, exchange rate, and tourism employment

As previously mentioned, tourism employment has traditionally been regarded as being determined by the number of tourists or by tourist spending, which ultimately represents the demand for tourism goods and services. Unlike such approaches, this study considers tourism employment to be a function of tourism GDP and the multilateral real exchange rate. In this section, I present the aspects that relate tourism employment to economic growth and the exchange rate.

The connecting link between economic growth and employment is among the most debated issues in the economic literature (Herman 2011 ). However, boosting economic growth is considered a key strategy in employment creation (Herman 2011 ; Wolnicki et al. 2006 ). In fact, the empirical literature has highlighted the existence of a positive relationship between employment and economic growth, although the quality of jobs created depends on a country’s situation, which is influenced by both the factors transmitting the effect of economic growth and complementary policies (Basnett and Sen 2013 ). Current evidence has also shown that employment expansion in any sector needs to be accompanied by both sectoral and economic changes; otherwise, it “is likely to hit a barrier” (Melamed et al. 2011 ).

Economic theory points out that employment and economic activity usually move in the same direction during periods of expansion as more production implies hiring more workers; accordingly, employment rises and unemployment falls (Burggraeve et al. 2015 ; Tangarife 2013 ). The relationship between employment and economic growth is established based on the aggregate production function, which can be expressed as \(Y=f\left(K,L\right)\) . This function states that the aggregate output ( \(Y\) ) is a function of both capital ( \(K\) ) and labor ( \(L\) ) (Mankiw 2000 ; Sudrajat 2008 ). To analyze the relationship between economic growth and employment, the aggregate production function can be simplified as \(Y=f\left(L\right)\) , and this equation represents the supply side, implying that the aggregate output is a function of employment; meanwhile, the demand side can be expressed as \(L=f(Y)\) , which states that employment is a function of the aggregate output (Sudrajat 2008 ).

However, unemployment does not necessarily fall at the same rate as employment increases, as both demographic factors and labor force participation influence the dynamics of the labor market (Burggraeve et al. 2015 ). Nonetheless, in Algeria, it was found that demographic and institutional factors only partially explained the level of unemployment (Bouklia-Hassane and Talahite 2008 ).

In addition, changes in unemployment are usually stronger during crises than during periods of economic expansion (Liquitaya and Lizarazu 2003 ). Furthermore, employment does not always grow as expected during expansion periods, an economic phenomenon known as “jobless growth” (Herman 2011 ). Examples of nations that have experienced jobless growth include Colombia (Tangarife 2013 ), India (Tejani 2016 ), Poland (Wolnicki et al. 2006 ), and South Africa (Temitope 2013 ), among others. Additionally, economies with high levels of labor market regulations tend to have higher unemployment rates than those with lower levels as these conditions make firms more reluctant to hire new employees (Neely 2010 ).

Regarding the output elasticity of employment, Basnett and Sen ( 2013 ) mentioned that this parameter indicates the level of job creation, although there may be a trade-off between the number of jobs generated and the value added per job. According to the same authors, employment elasticity analyses do not provide information on the quality of jobs created; therefore, special attention should be paid to the types of policies based on such studies.

However, employment also impacts economic growth as labor is an input of production, which can be calculated as the sum of jobs or employees. Nevertheless, according to Pilat and Schreyer ( 2003 ), this type of measure, despite its simplicity, presents different flaws; for example, it does not adequately measure changes in the quality of labor or the average work time per employee.

Concerning the exchange rate, a depreciation of the national currency implies that foreign products will become more expensive than domestic products and, thus, domestic consumers will demand fewer imported products, while foreign consumers will respond by demanding more exports from the nation whose currency has depreciated (Krugman et al. 2023 ). Effectively, an increase in the price level, when income remains constant, implies a contraction of the budget set, in the sense that there are fewer feasible consumption baskets (Varian 1999 ). As most consumption baskets contain imported goods, an increase in the price of imports negatively impacts domestic consumers (Krugman et al. 2023 ).

In tourism, as per Álvarez ( 1996 ), a depreciation of the national currency, on the one hand, boosts the reception of international tourists, but, on the other hand, diminishes domestic tourists’ spending. As tourism is a luxury good, according to the same author, a reduction in the purchasing power of domestic consumers more than proportionally reduces their spending on tourism goods and services. Meanwhile, according to Boullón ( 2009 ), inbound tourists’ spending, from an accounting perspective, represents a type of export. Nevertheless, Álvarez ( 1996 ) mentioned that a depreciation of the national currency does not necessarily increase the foreign currencies generated by tourism as it reduces international tourists’ average spending.

It is important to consider that tourism demand is more likely to be affected by the nominal values of exchange rates and prices than by real values. Moreover, in the short term, tourists may be unaware of the value of their national currency, which may cause them to be subject to money illusion (Stabler et al. 2009 ). Empirical evidence confirming the positive effect of the nominal exchange rate on international tourist arrivals has been reported in countries such as France (Chevillon and Timbeau 2006 ) and Mexico (Sánchez and Cruz 2016 ).

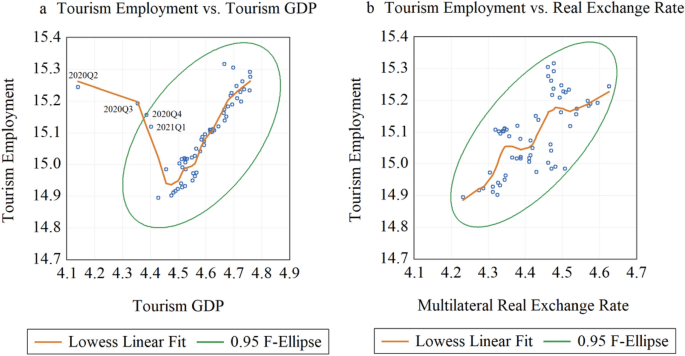

To exemplify the effect of both the multilateral real exchange rate and tourism GDP on direct tourism employment, I used multivariate analysis techniques consisting of control charts displaying scatter plots with nearest-neighbor fit. This analysis was complemented using confidence ellipses, as this technique permits detecting atypical data (Johnson and Wichern 2007 ). The series used in the control charts were transformed by applying seasonal adjustments and natural logarithms (Fig. 1 ).

Scatter plots with nearest-neighbor fit and confidence ellipses, 2006Q1–2021Q1

The atypical data shown in Fig. 1 a correspond to 2020Q2 and 2020Q3. During 2020Q2, the Mexican economy experienced the worst fall in history due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Cota 2020 ). Consequently, it brought about an increase in indicators related to poverty, social inequality, and disrupted labor markets, causing many residents to lose their jobs (Chiatchoua et al. 2020 ). However, direct tourism employment showed relatively high levels in 2020, although tourism GDP underwent important contractions, causing a change in the data trend (Fig. 1 a) and suggesting the existence of asymmetries.

This trend in tourism employment could be due to Mexico’s internal control of the pandemic because, as reported by Weiss ( 2021 ), the country did not close its borders and was among the few nations that did not require a negative COVID-19 test to enter its territory. Mexico occupied the third place in the list of the most visited countries in 2020, behind Italy and France (De la Rosa 2022 ; Weiss 2021 ). Moreover, in 2021, Mexico received 31.9 million tourists, which made it the second most visited nation that year, behind France (De la Rosa 2022 ; León 2022 ). Consequently, the entry of tourists allowed tourism companies to maintain a considerable number of jobs.

Finally, Fig. 1 b presents no atypical data in terms of confidence ellipses and shows that the depreciation of the Mexican peso stimulates jobs that are directly created by the tourism sector. The results presented in Fig. 1 b suggest the existence of a symmetric relationship between the multilateral real exchange rate and tourism employment.

Materials and methods

Data and sources.

To conduct this study, quarterly time-series data from the first quarter of 2006 to the first quarter of 2021 \(\left(N=61\right)\) were obtained from the following sources: tourism employment \(\left({E}^{T}\right)\) from Datatur (n.d.); the multilateral real exchange rate index with respect to 111 countries \(\left(\pi \right)\) from Banco de México ( 2021 ); and the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP (volume index, \(2013=100\) ), \(\left({Y}^{T}\right)\) , from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI 2021 ). As the multilateral real exchange rate index is provided on a monthly frequency basis, it was averaged into quarterly data.

The time-series data of tourism employment utilized in this study as an indicator of direct tourism employment, according to Datatur (n.d.), exclude induced and indirect employment. This series considers remunerated and subordinated workers, as well as self-employed workers, in tourism activities.

The Census X12 filter was applied to seasonally adjust the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP and the multilateral real exchange rate index. Applying this technique facilitates the detection of outliers, including the modeling of trading day and holiday effects (Hylleberg 2010 ). Meanwhile, the tourism employment series had already been seasonally adjusted by Datatur (n.d.). To avoid generating spurious results while computing the models, I tested the integration order of the series using breakpoint unit root tests (Table 1 ).

The results illustrate that \(\mathrm{ln}{\pi }_{t}\) is an \(I\left(1\right)\) series, whereas the tests provided mixed results for \(\mathrm{ln}{E}_{t}^{T}\) and \(\mathrm{ln}{Y}_{t}^{T}\) as these two series can be considered \(I\left(0\right)\) or \(I\left(1\right)\) in levels, depending on the test specifications. Therefore, I considered the ARDL and NARDL models to be adequate procedures for the purposes of this study.

Empirical design

To elaborate on the design of this study, unlike the previously mentioned classical approach, tourism employment was considered a function of the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP and the multilateral real exchange rate index as specified in Eqs. ( 1 ), ( 2 ), and ( 3 ):

Equation ( 1 ) represents the basic bivariate function. Meanwhile, Eqs. ( 2 ) and ( 3 ) are augmented by introducing the multilateral real exchange rate. Equation ( 3 ) allows for asymmetries in \({Y}^{T}\) , while Eq. ( 2 ) does not.

As mentioned by Sudrajat ( 2008 ), an important way of analyzing the relationship between economic growth and employment is based on Okun’s work. Particularly, Okun’s ( 1962 ) “fitted trend and elasticity” model provides a method to estimate the output elasticity of the employment rate. This study estimated the output elasticity of tourism employment using tourism employment and tourism GDP. Additionally, Eqs. ( 2 ) and ( 3 ) include the multilateral real exchange rate.

The ARDL methodology was selected to conduct the empirical estimation of Eqs. ( 1 ) and ( 2 ) as such an approach can function adequately regardless of whether the series are \(I\left(0\right)\) , \(I\left(1\right)\) , or a combination of both (Nkoro and Uko 2016 ; Phong et al. 2019 ). Meanwhile, Eq. ( 3 ) was approximated using a NARDL model, as NARDL models are based on the beneficial properties of ARDL models and are used to study the asymmetric impacts of the independent variables on the dependent variable (Phong et al. 2019 ). In addition, such models enable the discrimination of different forms and combinations of asymmetries as well as provide an easy estimation based on ordinary least squares (OLS) (Shin et al. 2014 ). Furthermore, once cointegration has been identified, NARDL models can be computed as regular ARDL models (Phong et al. 2019 ).

However, according to Sam et al. ( 2019 ), a prerequisite for applying the traditional F-bounds test proposed by Pesaran et al. ( 2001 ) is that the dependent variable should be an \(I\left(1\right)\) series. \(\mathrm{ln}{E}^{T}\) does not fully satisfy this condition because the breakpoint unit root tests show that such a series could be \(I\left(0\right)\) or \(I\left(1\right)\) in levels, depending on the test specifications (Table 1 ). To avoid generating spurious results derived from the cointegration methodology, the so-called “augmented ARDL bounds test for cointegration” developed by Sam et al. ( 2019 ) was applied. This allows testing for the existence of a levels relationship in the presence of an \(I\left(0\right)\) dependent variable.

All three models were computed using the restricted constant and no trend specification while utilizing series with natural logarithms to measure elasticities. Based on the conditional error correction regression, Eqs. ( 4 ) and ( 5 ) represent the ARDL models, whereas Eq. ( 6 ) represents the NARDL model:

where \({\varepsilon }_{A,t}\) , \({\varepsilon }_{B,t}\) , and \({\varepsilon }_{C,t}\) are the error terms. Meanwhile, \({\delta }_{A,t}\) , \({\delta }_{B,t}\) , and \({\delta }_{C,t}\) are variables designed to help the model correctly simulate the main breaks in the series, and are defined as shown in Eqs. ( 7 ), ( 8 ), and ( 9 ):

In Eq. ( 6 ), \(\mathrm{ln}{Y}_{t}^{T\left(+\right)}\) and \(\mathrm{ln}{Y}_{t}^{T\left(-\right)}\) are partial sums, which, following Shin et al. ( 2014 ), are calculated as shown in Eqs. ( 10 ) and ( 11 ):

To test the statistical significance of the asymmetries in Eq. ( 6 ), following Shin et al. ( 2014 ), the chi-square statistic of the Wald test was utilized. The null hypotheses of symmetry used to test long- and short-run relationships, following Olayeni’s ( 2019 ) examples, are shown in Eqs. ( 12 ) and ( 13 ), respectively, whereas Eq. ( 14 ) describes the joint test:

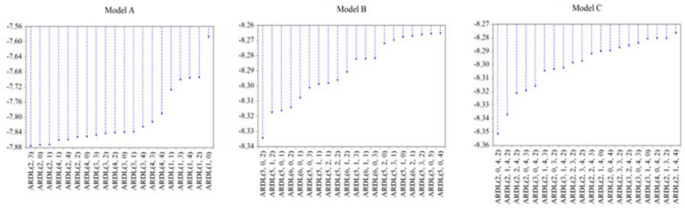

To determine the optimal number of lags, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used (Fig. 2 ). In Models A and C, a maximum of four lags was allowed. In Model B, a maximum of six lags was allowed.

Akaike information criteria (top 20 models)

The AIC results show that the optimal specifications are ARDL \(\left(\mathrm{2,3}\right)\) for Model A; ARDL \(\left(\mathrm{5,0},2\right)\) for Model B; and NARDL \(\left(\mathrm{2,0},\mathrm{4,2}\right)\) for Model C (Fig. 2 ). These results imply that, in the empirical estimation of Eqs. ( 5 ) and ( 6 ), it is necessary to use the term \(\mathrm{ln}{\pi }_{t}\) in the long-run path, instead of its lagged form, whereas the values related to \(\Delta \mathrm{ln}{\pi }_{t-i}\) are omitted from the short-run path of both equations.

Finally, as ARDL and NARDL models can be computed using the OLS methodology, the Quandt–Andrews unknown breakpoint test was applied to test for structural changes in the models. To estimate the NARDL model and its dynamic multiplier, the EViews NARDL add-in was employed, as per the instructions provided by Olayeni ( 2019 ).

Results and discussion

This study analyzed the effect of tourism GDP and the real exchange rate on the generation of tourism employment. To conduct the econometric analysis, correct specification tests were first applied to the ARDL and NARDL models (Table 2 ).

To complement the tests in Table 2 , the Quandt–Andrews unknown breakpoint test was applied (Table A1, Appendix), and it was found that all three models strictly satisfied the condition of no structural change. The stability of the models was verified by applying CUSUM and CUSUM of Squares tests to each model (Figures A1, A2, and A3).

Once it was verified that the models satisfied the correct specification tests, the conditional error correction regressions were computed (Table 3 ). The estimations in Table 3 were performed according to the optimal number of lags provided by the AIC (Fig. 2 ).

To test for level relationships, the augmented ARDL bounds test for cointegration was applied. It was found that all three models successfully satisfied the conditions imposed by this test (Table 4 ).

However, as remarked upon in the note accompanying Table 3 , the p value associated with \(\mathrm{ln}{E}_{t-1}^{T}\) is incompatible with t-bounds distribution. Nevertheless, as all three models were estimated using the restricted constant and no trend method (Case II), I used the critical values corresponding to the unrestricted constant and no trend method (Case III) to perform the test shown in Table 4 ; according to Sam et al. ( 2019 ), Case II is subsumed under Case III.

According to Shin et al. ( 2014 ), the F-bounds test depends on the number of variables entering the long-run relationship. However, when measuring asymmetries, it is not clear what the appropriate value of \(k\) should be as there is a dependency between partial sums. In this study, the partial sums were considered as different regressors, as shown in Table 4 , with \(k=3\) in Model C.

After confirming that the models fulfilled the correct specification tests and that the variables were cointegrated, the long-term coefficients and error correction terms were obtained (Table 5 ).

Negative signs in the error correction terms indicate convergence to equilibrium, while positive signs indicate divergence (Nkoro and Uko 2016 ). In Models A, B, and C, the rates of equilibrium adjustment are 6.83%, 6.49%, and 22.87%, respectively (Table 5 ).

According to Model A, when the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP increases by 1%, direct tourism employment increases by 1.47%. Meanwhile, according to Model B, when the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP increases by 1%, tourism employment increases by 1.26%. In both cases, the linear specifications show that tourism employment is elastic to changes in tourism GDP (Table 5 ). Model B also illustrates that the depreciation of the Mexican peso has positive effects on tourism employment: for each 1% increase in the multilateral real exchange rate index, tourism employment increases by 0.40% (Table 5 ). In the short term, both Models A and B show that tourism GDP growth stimulates the tourism sector’s capacity to create jobs. However, Model B shows that the real exchange rate has no effect on direct tourism employment (Table 3 ).

Before analyzing the results of Model C, it is important to corroborate the statistical existence of asymmetries by testing the null hypotheses in Eqs. ( 12 ), ( 13 ), and ( 14 ) using the Wald test (Table 6 ).

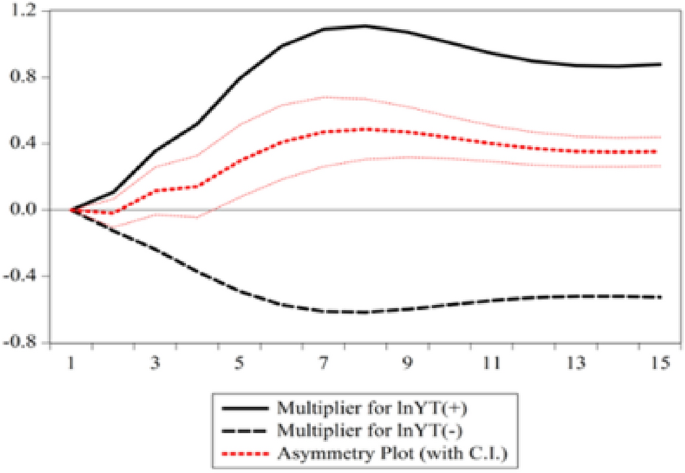

The Wald test rejects the null hypothesis of long-term symmetric adjustment in Eq. ( 12 ); however, it does not reject the null hypothesis in Eq. ( 13 ); thus, there is no evidence of asymmetries in the short term (Table 6 ). Figure 3 shows the multiplier effect of tourism GDP on tourism employment with its shocks.

Tourism GDP dynamic multiplier

Given the results in Table 5 , Model C demonstrates that tourism employment is inelastic to changes in the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP. If the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP increases by 1%, tourism employment increases by 0.90%. Conversely, if the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP decreases by 1%, tourism employment decreases by 0.52%. Model C also shows that tourism employment responds positively to the depreciation of the Mexican peso. However, a 1% increase in the multilateral real exchange rate index generates only a 0.10% increase in tourism employment (Table 5 ).

Overall, the results suggest that Model C is better equipped to model tourism employment than Models A and B, as Model C has a smaller AIC value (Fig. 2 ). Model C also converges faster to equilibrium than Models A and B; in terms of absolute values, it presents a larger error correction term (Table 5 ).

Conclusions and policy implications

This study documents the impact of both the quarterly indicator of tourism GDP and the multilateral real exchange rate on direct tourism employment. The empirical approach employed consisted of applying the ARDL and NARDL methodologies to estimate the output elasticity of employment in the Mexican tourism sector.

The results indicate that both linear models are consistent with traditional approaches that claim tourism is an employment-intensive sector, as both models exhibit an output elasticity of tourism employment greater than unity. Meanwhile, the nonlinear model shows that tourism employment is inelastic to both positive and negative changes in tourism GDP. However, Model C indicates that tourism employment is more elastic to a positive change in tourism GDP than to a negative change. In other words, Model C shows that, in the long term, expansions in tourism GDP create more employment than is lost due to contractions. Thus, Models A and B could be overestimating the impact of tourism GDP on the creation of direct employment.

Meanwhile, the results in Models B and C show that, in the long term, real exchange rate variations exert a sufficiently strong impact on tourism demand to induce a statistically significant effect on the level of tourism employment, although such an effect is inelastic (Table 5 ). In addition, both models demonstrate that, in the short term, the multilateral real exchange rate has no effect on tourism employment (Table 3 ). This result is congruent with Stabler et al.’s ( 2009 ) observation that tourists may be unaware of their national currency value in the short term, implying that tourism demand is not sufficiently stimulated to produce a change in employment level.

All three models demonstrate that the Mexican tourism sector has a great capacity to generate direct employment during its expansion periods. Moreover, the results of Model C document the resilience of tourism employment during crises. In this sense, it is necessary to consider that the Mexican tourism sector demand was stimulated by the internal control of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading the country to achieve an unusually high position in the ranking of the most visited countries (Weiss 2021 ), while stimulating tourism companies to maintain an important level of occupation. Nevertheless, as mentioned by Paredes ( 2022 ), once travel conditions become normalized, Mexico will probably revert to the same place it had in the rankings before the pandemic.

The results in Fig. 1 a show a negative trend in the relationship between direct tourism employment and tourism GDP from 2020Q2 to 2021Q1, whereas there is a positive and mostly linear relationship for the rest of the study period. This suggests that the asymmetric impact of tourism GDP on tourism employment could have been introduced as an effect of the pandemic. However, it is necessary to conduct further research to confirm this observation.

Although the results of this study are congruent with the well-established notion that tourism contributes to national economies by creating employment, it is important to consider that elasticity analyses do not provide information on the quality of jobs generated. For example, according to Robinson et al. ( 2019 ), tourism also contributes to creating deep social cleavages, economic inequalities, and precarious employment conditions. Ferguson ( 2010 ) mentioned that the tourism sector creates a significant number of unpaid jobs as a result of numerous tourism micro-businesses; for example, it results in unpaid family members working in the hotel and restaurant trade. In the case of Mexico, Wilson ( 2008 ) noted that tourism has increased the number of workers employed in precarious occupational conditions, and made the country more dependent on foreign loans and patronage.

A final consideration of these results is that growth in the tourism sector can create a considerable number of jobs. However, the above-mentioned observations regarding the quality of tourism employment challenge the vision of tourism as a force for alleviating poverty. In this context, as Basnett and Sen ( 2013 ) noted, it is important to carefully consider employment output elasticity when designing economic policies. In this sense, such analyses should be complemented by studies on the effect of tourism on the complementary rates of occupation, such as the underemployment rate, the rate of informal employment, or the rate of critical occupancy conditions.

Limitations

This study estimated the output elasticity of tourism employment; therefore, it is not possible to make conclusions on the quality of employment created by the tourism sector in Mexico. Additionally, the tourism employment time-series data exclude induced and indirect employment, and thus, the models do not consider all types of employment created by the tourism sector. In addition, according to Datatur (n.d.), due to the COVID-19 outbreak, there was a change in the computation methodology of tourism employment; therefore, the results of the second quarter of 2020 correspond to the Telephone Survey of Occupation and Employment (ETOE). Finally, as mentioned in this paper, tourism GDP corresponds to a volume index.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at Mendeley Data at https://doi.org/10.17632/vy6wyfr33k.1

Abbreviations

Aggregate output

Akaike information criterion

Autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity

Autoregressive distributive lag

Breusch–Godfrey

Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey

Error correction mechanism

Gross domestic product

Multilateral real exchange rate

Ordinary least squares

Regression equation specification error test

- Tourism employment

- Tourism GDP

World health organization

Álvarez P (1996) La relación de los servicios y el turismo con el sector externo en México. Comercio Exterior 46:148–157

Google Scholar

Banco de México (2021). Sistema de Información Económica: Índice de Tipo de Cambio Real con Precios Consumidor y con respecto a 111 países - (CR60), https://www.banxico.org.mx/SieInternet/consultarDirectorioInternetAction.do?sector=6&accion=consultarCuadro&idCuadro=CR60&locale=es . Accessed 24 Oct 2021

Basnett Y, Sen R (2013) What do empirical studies say about economic growth and job creation in developing countries? Helpdesk Request. EPS PEAKS, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08a2340f0b652dd0005a6/Growth_and_labour_absorption.pdf

Bhattarai K, Upadhyaya G, Bohara SK (2021) Tourism, employment generation and foreign exchange earnings in Nepal. J Tour Hosp Educ 11:1–21. https://doi.org/10.3126/jthe.v11i0.38232

Article Google Scholar

Bote V (1990) Planificación Económica del Turismo: De una Estrategia Masiva a una Artesanal. Trillas, Mexico

Bouklia-Hassane R, Talahite F (2008) Marché du travail, régulation et croissance économique en Algérie. Rev Tiers Monde 194:413–437. https://doi.org/10.3917/rtm.194.0413

Boullón RC (2009) Las Actividades Turísticas y Recreacionales: El Hombre como Protagonista. Trillas, Mexico

Burggraeve K, De Walque G, Zimmer H (2015) The relationship between economic growth and employment. Econ Rev i:31–50

Caballero P (2011) Estacionalidad turística y temporalidad del empleo ¿Reservas de eficiencia? Cuba: Investig. Econ 17:26–56

Chevillon G, Timbeau X (2006) L’impact du taux de changé sur le tourisme en France. Rev OFCE 98:167–181. https://doi.org/10.3917/reof.098.0167

Chiatchoua C, Lozano C, Macías-Durán JE (2020) Análisis de los efectos del COVID-19 en la economía mexicana. RECEIN Univ La Salle 14:265–290. https://doi.org/10.26457/recein.v14i53.2683

Cota I (2020) La Economía Mexicana se desploma un 17.3% en el Segundo Trimestre de 2020, la peor Caída de su Historia. El País , https://elpais.com/mexico/economia/2020-07-30/la-economia-mexicana-se-desploma-un-173-en-el-segundo-trimestre-de-2020-la-peor-caida-de-su-historia.html . Accessed 20 Oct 2022

Dahdá J (2003) Elementos de Turismo: Economía, Comunicación, Alimentos y Bebidas, Líneas Aéreas, Hotelería, Relaciones Públicas. Trillas, Mexico

Datatur (n.d.). Empleo Turístico. http://www.datatur.sectur.gob.mx/SitePages/ResultadosITET.aspx . Accessed 23 Oct 2021

De la Rosa A (2022) México fue el segundo país más visitado en 2021: OMT. El Economista, https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/empresas/Mexico-fue-el-segundo-pais-mas-visitado-en-2021-OMT-20220329-0012.html . Accessed 25 Nov 2022

Domínguez KI, Vargas EE, Zizumbo L, Velázquez JA (2021) Tourism jobs and quality of work-life. A perception from the hotel industry workers. Cuadernos Admón. 37:e2310718. https://doi.org/10.25100/cdea.v37i69.10718

Ferguson L (2010) Tourism as a development strategy in central America: exploring the impact on women’s lives. CAWN briefing paper: March 2010. Central America Women’s Network, London

Ghose AK (2015) Services-led growth and employment in India. In: Ramaswamy KV (ed) Labour, Employment and Economic Growth in India. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 57–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316156476.004

Chapter Google Scholar

Gurrieri AR, Lorizio M, Stramaglia A (2014) Tourism: A service sector. Entrepreneurship Networks in Italy. Springer, Cham, pp 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03428-7_3

Hartrich S, Martínez D (2020) Accelerating Tourism’s Impact on Jobs. Lessons from Market System Analysis in Seven Countries. International Labour Office, Geneva

Herman E (2011) The impact of economic growth process on employment in European Union countries. Rom Econ J 14:47–67

Hipsher S (2017a) Poverty reduction and wealth creation. Poverty reduction, the private sector, and tourism in mainland Southeast Asia. Palgrave MacMillan, Singapore, pp 55–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5948-3_3

Hipsher S (2017b) Tourism: Job creation, entrepreneurship, and quality of life. Poverty reduction, the private sector, and tourism in mainland Southeast Asia. Palgrave MacMillan, Singapore, pp 231–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5948-3_11

Hylleberg S (2010) Seasonal adjustment. In: Durlauf SN, Blume LE (eds) Macroeconometrics and time series analysis. Palgrave MacMillan, London, pp 210–226. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230280830_24

INEGI (2021) Banco de información económica, https://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/bie/ . Accessed 23 Oct 2021

Ioannides D, Gyimóthy S, James L (2021) From liminal labor to decent work: a human-centered perspective on sustainable tourism employment. Sustainability 13:851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020851

Johnson RA, Wichern DW (2007) Applied multivariate statistical analysis. Prentice Hall-Pearson, Upper Saddle River

Jolliffe L, Farnsworth R (2003) Seasonality in tourism employment: human resource challenges. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 15:312–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110310488140

Knotek ES (2007) How useful is Okun’s Law? Econ. Rev.-Fed Reserve Bank Kans City 92:73–103

Krugman PR, Obstfeld M, Melitz MJ (2023) International economics: theory and practice. Pearson Education, New York

León C (2022) México, el segundo país más visitado del mundo. Revista Fortuna, https://revistafortuna.com.mx/2022/04/14/mexico-el-segundo-pais-mas-visitado-del-mundo/#:~:text=De%20acuerdo%20con%20datos%20del,millones%20900%20mil%20turistas%20extranjeros . Accessed 25 Nov 2022

Liquitaya JD, Lizarazu E (2003) La Ley de Okun en la economía mexicana. Denarius 8:15–39

Mankiw NG (2000) Macroeconomía. Antoni Bosch, Barcelona

Melamed C, Hartwig R, Grant U (2011) Jobs, growth and poverty: what do we know, what don’t we know, what should we know? Overseas Development Institute, London

Neely CJ (2010) Okun’s Law: output and unemployment. Econ. Synop 2010:1–2. https://doi.org/10.20955/es.2010.4

Nkoro E, Uko AK (2016) Autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) cointegration technique: application and interpretation. J Stat Econ Methods 5:63–91

Okun AM (1962) Potential GNP: its measurement and significance. In: Cowles Foundation, paper 190. Reprinted from the 1962 Proceedings of the Business and Economic Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association

Olayeni OR (2019) NARDL: implementation using EViews add-in . Research Gate Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30251.59687

Panosso A, Lohmann G (2012) Teoría del Turismo: Conceptos, Modelos y Sistemas. Trillas, Mexico

Paredes, M. (2022). México es el segundo país del mundo que más atrajo turistas internacionales en 2021. Dinero en Imagen, https://www.dineroenimagen.com/actualidad/mexico-es-el-segundo-pais-del-mundo-que-mas-atrajo-turistas-internacionales-en-2021 . Accessed 25 Nov 2022

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16:289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

Phong LH, Van DTB, Bao HHG (2019) A nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) analysis on the determinants of Vietnam’s stock market. In: Kreinovich V, Thach N, Trung N, Van Thanh D (eds) Beyond traditional probabilistic methods in economics. Springer, Cham, pp 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04200-4_27

Pilat D, Schreyer P (2003) Measuring productivity. OECD Econ Stud 2001(2):127–170. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-v2001-art13-en

Prasad N, Kulshrestha M (2015) Employment generation in tourism industry: an input-output analysis. Ind J Labour Econ 58:563–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-016-0035-2

Ramírez C (1994) La Modernización y Administración de Empresas Turísticas. Trillas, Mexico

Robinson RNS, Martins A, Solnet D, Baum T (2019) Sustaining precarity: critically examining tourism and employment. J Sustain Tourism 27:1008–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1538230

Sam CY, McNown R, Goh SK (2019) An augmented autoregressive distributed lag bounds test for cointegration. Econ Modell 80:130–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.11.001

Sánchez F, Cruz JN (2016) Determinantes económicos de los flujos de viajeros a México. Rev Anal Econ 31:3–36. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-88702016000200001

Santos E (2023) Does inbound tourism create employment? In: Santos E, Ribeiro N, Eugénio T (eds) Rethinking Manageme nt and Economics in the New 20’s. Springer, Singapore, pp 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-8485-3_22

Shin Y, Yu B, Greenwood-Nimmo M (2014) Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In: Sickles R, Horrace W (eds) Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt. Springer, New York, pp 281–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-8008-3_9

Sigala M (2020) Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J Bus Res 117:312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

Stabler MJ, Papatheodorou A, Sinclair MT (2009) The economics of tourism. Routledge, London

Book Google Scholar

Sudrajat LW (2008) Economic growth and employment: analysis the relationship between economic growth and employment in Indonesia period 1993–2003. Institute of Social Studies, The Hague

Tangarife CL (2013) La economía va bien pero el empleo va mal: Factores que han explicado la demanda de trabajo en la industria colombiana durante los años 2002–2009. Perfil Coyuntura Econ 28:39–61

Tejani S (2016) Jobless growth in India: an investigation. Camb J Econ 40:843–870. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bev025

Temitope LA (2013) Does economic growth lead employment in South Africa? J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 5:336–345. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v5i6.409

Tribe J (2011) The economics of recreation. Leisure and Tourism, Routledge, London

Varian HR (1992) Microeconomic analysis. W. W. Norton & Company, New York

Varian HR (1999) Microeconomía Intermedia: Un Enfoque Actual. Antoni Bosch, Barcelona

Walmsley A (2017) Overtourism and underemployment: a modern labour market dilemma . In: 13th International Conference on Responsible Tourism in Destinations. Icelandic Tourism Research Centre, Reykjavik

Weinz W, Servoz L (2011) Poverty reduction through tourism. International Labour Office, Geneva

Weiss S (2021) México brilla como destino turístico. Pese al COVID-19. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/es/m%C3%A9xico-brilla-como-destino-tur%C3%ADstico-pese-al-covid-19/a-56593033 . Accessed 9 Oct 2022

WHO (2020) WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19, https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19 . Accessed 11 Mar 2020

Wilson TD (2008) Economic and social impacts of tourism in Mexico. Lat Am Perspect 35:37–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X08315758

Wolnicki M, Kwiatkowski E, Piasecki R (2006) Jobless growth: a new challenge for the transition economy of Poland. Int J Soc Econ 33:192–206. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290610646225

Yang J, Wu Y, Wang J, Wan C, Wu Q (2021) A study on the efficiency of tourism poverty alleviation in ethnic regions based on the staged DEA Model. Front Psychol 12:642966. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.642966

Download references

Acknowledgements

Fernando Sánchez López is a PhD Candidate from Programa de Posgrado en Economía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and has received a fellowship from CONAHCYT.

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico

Fernando Sánchez López

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

FSL is the only author.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fernando Sánchez López .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 191 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Sánchez López, F. The role of the tourism sector in creating direct employment in Mexico: evidence from linear and nonlinear ARDL frameworks. SN Bus Econ 3 , 213 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-023-00584-4

Download citation

Received : 14 June 2023

Accepted : 19 October 2023

Published : 23 November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-023-00584-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic growth

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World Research Paper

The increasing cases of unemployment in most countries are alarming. Most governments are trying to create various ways of providing jobs for their residents.

One sector that has potential to offer jobs to many people is the tourism industry. This paper is going to review several literature sources in order to describe the relationship and link between tourism and employment in the present world.

Tourism industry is among the leading and most vibrant industries in the current global economy. Projections in the tourism industry indicate that the industry will cover 9 percent of total GDP and offer over 235 million occupations representing 8 percent of the worldwide employment in a few years from now (ILO News par.3).

Evaluated against other segments of the worldwide economy, the tourism sector is among the fastest growing sectors comprising over a third of the overall global services trade (ILO News par.3).

Most governments rely on the tourism sector for job creation. The South African government recognizes the significance of this sector since at least one job becomes created for each 16 tourists who visit the nation (Brand South Africa par.5).

Zuma, the president of South Africa, is optimistic that the increase in number of tourists is a chief way of dealing with unemployment in the country.

In 2010, the number of tourists visiting South Africa increased by a million, and presently the country is seeking to increase the number of global conferences and sports occasions in an effort to increase tourist arrivals (Brand South Africa par. 5).

Tourists’ consumption expenditures offer direct or indirect employment openings in the tourism industry. Every tourist spending empowers the tourism segment directly as well as other segments which provide input to the tourism industry indirectly to produce employment capacity (ILO News par.2).

Also, tourism has an effect on total employment of a nation through the common impacts of employment on the economy (Onder and Ayse 365).

Service is a fundamental aspect in the tourism segment. Tourism segmnet requires workers to deal with both production and offering services (Onder and Ayse 366). The sector comprises a vast deal of employment areas because of its labor intensive fabrication (ILO News par.6).

The industry has high labor intensity, and this makes the sector a noteworthy source of employment. While there are technological advancements in this industry, such technologies reduce the need for employees modestly because of restricted use of computerization and mechanization in the tourism sector.

Hence, tourism growth has led to generation of numerous job openings both in emerging and developed nations.

Employment in the tourist sector became affected by the global economic crisis. The ILO News revealed that the global economic crisis affected global tourism. (par.3). At the same time, ILO News projected that rampant growth was likely to occur in coming years, thus creating an increased number of jobs (par.3).

As from the second half of 2008, the tourism industry started experiencing a decline, which grew immensely in 2009. Rapid decline in duration of stay and expenditure, tourist travels as well as augmented limitations on business travel expenses caused a momentous reduction of economic activity in the global tourist industry.

However, global employment in the industry rose by 1% between 2008 and 2009 with noteworthy regional disparities with regard to the effect of the crisis on levels of employment (ILO News par.4).

While tourism sector has potential to create many jobs, employees in this sector require diverse skills. The ILO News positions tourism as a supreme job creator that needs different levels of skills (par.5). Such skills can be enhanced through vocational training and education.

The ILO News reveals that most workers in the tourism sector have inadequate professional qualifications, and thus there is a need for further training on key issues such as health (par.5).

This can be steered by the growing impact of technology, environmental concerns as well as demanding customers. Besides, efficiency and competitiveness in the sector rely on professionalism, skills and dedication of the employees.

Different nations advocate for skill development programs in order to enhance the process of job creation in the tourism factor. For instance, Shri Subodh Kant Sahai of India has ordered additional efforts on skill development program in his tourism ministry in order to enhance the process of job creation in the tourism sector (Travel trade journal.com par.1).

People trained under this program were gained over into different prominent chains of hotels where they are currently doing extremely well (Travel trade journal.com par.2). An example of a skill development program in India is the Hunar Se Rozgar scheme.

The proprietor of this program plans to extend the program to incorporate new trade courses such as retail marketing, driving, and reception. The idea behind the provision of these courses is that they can promote job creation features in accordance with the industry demand.

Besides, there exists a direct connection between tourism sector and other industries including lodging, transport, management, travel agents, entertainment, health and finance (Travel trade journal.com par.2).

Tourism can generate three employment forms in states and regional markets including indirect employment, direct employment and induced employment (Mathieson and Geoffrey 77).

Indirect employment comprises employment in other industries that never provide directly to touristic clients, although, they obtain revenue from payments done in touristic dealings with other industries that supply input for tourism segment.

Examples of employees who can be included in the category of indirect employment include persons employed in building an extra unit to expand capacity of a housing facility, or workers employed in a production facility, which creates the material to be erected for transaction in this facility.

Direct employment is the employment that becomes offered in tourism facilities like food, housing, food, travel agents and shipping, which subsist in the tourism industry and provide with needs of tourists directly (Mathieson and Geoffrey 77).

Further, induced employment denotes the supplementary employment that occurs due to reutilization of the proceeds obtained through indirect and direct employment ways. People, whose earnings and life standards rise due to their tourism actions generate new employment openings by spending their earnings in other segments of the economy.

Establishing the exact impact of tourism on employment is a complex task. Homafar et al. give some reasons as to why it is difficult to establish the impact of tourism on employment (35). First, most people who work in the tourist sector can barely be differentiated from those that work in identical or comparable positions unrelated to tourism.

For example, official data relates lodging facilities with food facilities such as restaurants. Besides, employment in diverse sectors of the transport industry obtains representation without regarding to the relationship with tourism.

Again, there exist several small firms that offer tourism services, and the proportions of persons who work in self enterprises hardly obtain consideration while computing the total workforce. As a result, employment figures for tourism segment are not likely to demonstrate the real circumstance.

Further, tourists activities increase in some months and the amount of people employed in tourism services vary significantly from time to time. Onder and Ayse explain that the impact of tourism on employment amplifies depending on expansion in tourism and force (367). Tourism generates both employment and revenue.

Tourism can build employment facilities in both tourist sending areas and tourist receiving areas, in dissimilar ratios since different service departments obtain use in sender nations in order to execute some facilities required ahead of travel.

For instance, insurance, cargo and telephone activities must be carried out prior to travel. However, Onder and Ayse acknowledge that a comparison between job creation in tourists receiver states and tourist sending nations demonstrates that receiver countries benefit more in terms of job creations than sending nations (367).

Some issues employees are facing in the tourist sector include low payments, lack of social security and increased cases of personnel transfer. Tourism is a seasonal activity, which makes the industry prone to be influenced by negative advances in politics and economy (Homafar et al. 36). For instance, low economic situation may cause the sector to pay low wages to employees.

There exist many aspects of tourism in regard to employment. First, the seasonal nature of tourism allows underemployment thus making employment in the sector to be a seasonal phenomenon.

Second, the impact of employment in the tourism industry is normally a veiled one because the industry shifts manpower from other segments and nearly all workers in the industry lack insurance.

Third, the fact that skilled workers obtain permanent employment while unskilled employees obtain impermanent employment causes low, work productivity, which weakens economic growth in the tourism industry.

Full employment may be attained during peak seasons, although the decline in employment during low seasons brings many social costs. Efforts to eradicate these costs may include employing interns or related personnel who are usually free during peak seasons.

Fifth, women in the tourism industry comprise a bigger proportion than women in other industries. The last but not least, the sector offers employment chances mainly to people with similar investment quantities because the capital amount that is essential for generating business dimensions for a single person is less than other industries.

In conclusion, studies on tourism and employment demonstrate that tourism has desirable effects on employment. The industry is labor intensive and thus, creates a vast number of employment facilities.

Tourism facilities profit from labor personnel in both manufacturing and distributing tourism products. Tourists’ payments act as a source of wages to employees in the tourism sector. While there are technological advancements in the tourism industry, they reduce the need for employees modestly owing to restricted use of computerization and mechanization in the tourism sector.

Employees in the tourism sector require training and skill development as the industry requires different levels of skills. Finally, decline in the span of stay and expenditure, tourist travels as well as augmented limitations on business travel affect economic activities in the global tourist industry, including employment.

Works Cited

Brand South Africa. 2011 South Africa’s Year of Job Creation: Zuma. 2011. Web.

This article discusses several initiatives proposed by Zuma, the president of South Africa for enhancing job creation. This piece is relevant to this study as it recognizes the value of tourism in job creation.

The president explains that the country seeks to increase the number of global conferences and sports occasions, with the ultimate objective of creating jobs.

Homafar, Fazele, Habib Honari, Akbar Heidary, Taghi Heidary and Afsane Emami. “The Role of Sport Tourism in Employment, Income and Economic Development.” Journal of Hospitality Management and Tourism 2.3 (2011): 34-37. Print.

This article is a survey on perceptions of managers and tourism ideas about the role of sports induced tourism in employment creation. This piece of work is significant for this study as it demonstrates the relationship between tourism and employment.

ILO News. Employment in the Tourism Industry to Grow Significantly . 2010. Web.

This article represents a discussion of a global forum held by delegates from different countries in order to discuss challenges facing the tourism industry.

This article is significant for the study as it describes the growth of tourism and employment in the industry through the global crisis. The article also highlights the need for training and education in developing employment in the sector.

Mathieson, Alister and Geoffrey Wall. Tourism: Economic, Physical and Social Impact . London, Harlow: Pearson Education, 2010. Print.

This book discusses economic, social and physical impacts of tourism. The book is significant for this study as it describes how tourism can generate different forms of employment.

Onder, Kubra and Ayse Durgun 2010, Effects of Tourism Sector on Employment in Turkey: An Econometric Application. Web.

This article discusses the situation of the tourism industry in Turkey, especially after 1980. The article is significant for this study as it uses an empirical approach to demonstrate the relationship between tourism and employment.

Travel trade journal.com. n. d. Ministry of Tourism: Subodh Kant Inaugurates National Workshop on Hunar Se Rozgar . Web.

This article includes the words of Shri Subodh Kant Sahai, who is a tourism minister in India. The article emphasizes on the need for skill development in the tourism sector.

This piece is significant for this research as it demonstrates that equipping young people with new skills facilitates job creation in the tourism industry.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 12). Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/

"Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World." IvyPanda , 12 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World'. 12 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World." January 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/.

1. IvyPanda . "Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World." January 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World." January 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/.

- International Labour Organisation in Australia

- Labor Market: Equality Promotion

- Legislative Changes Need in the Current Uae Labour Law

- Ohio Alliance to End Sexual Violence Seeking Community Safety

- Trade Unions History and Development

- Health and Safety Laws in the Oil and Gas Sector

- Child Labor Controversy and Regulations

- Merger & Acquisition in the Public Service Commission

- Child Labor in Turkish Cotton Industry

- Tourism in a Goa

- Benefits of Tourism

- Eco Tourism and Hospitality Industry

- Socio Economic Impacts of the “Enclave Tourism” Development

- Assessing the future for high street travel agents in the UK

- The tourism sector in the Australia Capital Territory

Report | Jobs and Unemployment

Updated employment multipliers for the U.S. economy

Report • By Josh Bivens • January 23, 2019

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

When it comes to the ripple effects that spread to the rest of the labor market, one lost dollar of economic output or one lost job is not the same as another.

Each industry has backward linkages to economic sectors that provide the materials needed for the industry’s output, and each industry has forward linkages to the economic sectors where the industry’s workers spend their income. Therefore, in addition to the jobs directly supported by an industry, a large number of indirect jobs may also be supported by that industry. The subtraction (or addition) of jobs and output in industries with strong backward and forward linkages to other economic sectors can cause large ripple effects.

This brief calculates employment multipliers by industry to illustrate the importance of these linkages, updating earlier work by Bivens (2003) and Baker and Lee (1993). Employment multipliers measure how the creation or destruction of output or employment in a particular industry translates into wider employment changes throughout the economy.

Background and findings

Production in a given economic sector involves linkages with other sectors—that is, production in one industry depends on suppliers in other industries ( backward linkages ), while wages earned in the production and supplier sectors are spent in other economic sectors ( forward linkages ). In the case of automobile production, there are backward linkages to industries that produce tires, glass for windshields, and steel for automobile frames (among many others). Forward linkages occur when automobile workers (and suppliers’ employees) spend their income in restaurants and retail stores and at the doctor (to name just a few).

Industries that are heavy users of materials are vital to their suppliers. If an automobile factory were to close, its suppliers in the glass, steel, and rubber industries would have a big hole to fill in demand for their own output. Industries that pay higher wages are vital to their forward-linked industries. If a steel factory closed, surrounding restaurants and retail malls would also have a big hole to fill in demand for their output.

There are two obvious ways to measure how intensive an industry’s backward and forward linkages are to the rest of the economy. The first estimates the ripple effects of a given number of jobs being lost directly in an industry. In this case, the direct job loss is assumed to be, say, 100, and then the resulting backward and forward ripple effects can be estimated. The second takes a given dollar value of final demand for an industry’s output and calculates how much of this final demand spills over into backward- and forward-linked industries. An example would be assessing the impact of a fall of $1 million in final demand for autos (that is, $1 million less being spent on cars by consumers). This fall in final demand would cost jobs directly in the auto production industry, but would also cause demand to fall in supplier industries and in forward-linked industries that rely on automobile workers (and on workers in the supplier industries) to purchase their output. With the right data, researchers can empirically estimate the number of jobs lost in each link of these chains.

There are virtues and drawbacks to both the output and the employment measures as the bases of employment multipliers (as discussed in the methodology appendix); this paper presents estimates using both measures.

Examples: Employment multipliers by jobs lost or by output lost

Would the closing of a factory that manufactures durable goods and employs 1,000 people have a greater impact on the overall economy than the closing of a retail shopping mall that employs 1,000 people? The direct impacts (1,000 jobs lost) are the same; employment multipliers can show us what the total indirect effects will be. As seen in Table 1 , the number of indirect jobs lost for every 100 direct jobs lost are 744.1 for durable manufacturing and 122.1 for retail trade. Therefore, the estimated total number of indirect jobs lost if the auto factory closed would be 7,441; the estimated indirect job loss if the shopping mall closed would be 1,221.

We use a similar example to look at the question from a different angle: What are the effects on jobs when the demand for output drops by a certain amount? Specifically, would the disappearance of $1 million in final demand for output from factories producing durable goods have the same aggregate jobs impact as the disappearance of $1 million in retail? In this case, the direct jobs lost in durable manufacturing stemming from a $1 million reduction in final demand would be smaller—about two jobs in durable goods manufacturing compared with about 10 jobs in retail. (See Table 2 , “durable manufacturing” and “retail trade” rows.) This is because durable goods production is far more productive than retail and hence fewer direct jobs are needed per dollar of output. However, the backward and forward linkages for durable goods cause this direct output loss to ripple far more widely throughout the job market. The employment multipliers in Table 1 show a total of 16.5 indirect jobs lost per $1 million drop in demand for durable manufacturing, compared with 10.6 indirect jobs lost for the same demand drop in retail. This means that, while direct job loss is much lower in durable manufacturing, total job loss (including both indirect and direct jobs) for a $1 million drop in demand is similar in durable manufacturing and retail (18.3 and 20.5, respectively).

The summary findings for major industry groups are provided in Tables 1 and 2. The appendix describes our methodology in detail, and Appendix Tables A1 and A2 provide the employment multipliers for all 179 industries tracked by the data sources we use in this paper. Finally, an accompanying spreadsheet providing the raw data is being released with this paper for those interested in exploring the multipliers. 2

Employment multipliers per 100 direct jobs, by major private-sector industry group

* Includes materials and capital services supplier jobs

** Includes jobs supported by respending of income from direct jobs and supplier jobs, as well as public-sector jobs supported by tax revenue

Notes: See methods appendix for derivation. The industry-specific multipliers from Appendix Table A1 are weighted and summed across industries within major industry groups to get the multipliers in this table. For the per-100-jobs multipliers, the weight used is hours of work (weights are included in the Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment Requirements Matrices data).

Source: EPI analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Employment Requirements Matrices, the BLS Current Employment Statistics program, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis GDP-by-industry accounts

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Employment multipliers per $1 million in final demand, by major private-sector industry group

Notes: See methods appendix for derivation. The industry-specific multipliers from Appendix Table A2 are weighted and summed across industries within major industry groups to get the multipliers in this table. For the per-$1-million multipliers, the weight used is an output weight (weights are included in the Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment Requirements Matrices data).

Source: EPI analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Employment Requirements Matrices, the BLS Current Employment Statistics program, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis GDP-by-industry accounts

An understanding of employment multipliers—the degree of backward and forward linkages that exists between industries—may often be useful to policymakers and analysts. As an example, the three largest U.S. automobile firms (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler) directly employ substantially less than 200,000 workers in the United States. Yet it was widely (and correctly) considered imperative among policymakers to not let these firms fail and become casualties of the financial crisis of late 2008. This belief from policymakers was driven by the fully rational fear that the substantial backward and forward linkages from auto assembly jobs would be large enough to cause mammoth ripple effects throughout the economy. Without understanding the scope of these effects, this decision would be harder to understand.

This report makes these linkages concrete and measurable by calculating employment multipliers two ways and provides estimates for 179 private-sector industries. It also provides a methodology and accompanying spreadsheet to allow others to experiment with calculations.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by support from the Alliance for American Manufacturing .

Appendix: Data methods for calculating employment multipliers, per dollar and per job

In this report, I estimate two broad categories of indirect job impacts that are spurred by direct employment changes in a given industry: supplier jobs and induced (or respending) jobs (including public-sector jobs). The first category (supplier jobs) defines the backward linkages of an industry. Induced jobs define forward linkages. The total of these influences make up the “employment multiplier.”

I calculate the employment multipliers on two different bases: per each 100 jobs in an industry and per each $1 million of final demand for an industry’s output.

Supplier jobs

Supplier jobs are generally the most intuitive category of indirect employment changes. Put simply, when jobs are lost in one industry, the industries that provide inputs and materials also suffer losses. Take a concrete example: When coal-mining activity shrinks, it leads to a reduction in demand for industries that provide inputs to coal mining, such as those that provide safety equipment, industrial equipment, and/or transportation equipment and services.

Supplier job estimates can be calculated directly from the employment requirements matrices (ERM) provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The BLS ERM shows how many jobs are supported by $1 million in final demand in a given industry, jobs both in the industry directly satisfying the final demand as well as ones supplying inputs. For example, each $1 million in final demand for construction services supports jobs in the construction industry, but also supports jobs in concrete production, bulldozer manufacturing, and accounting services. The ERM tracks how many jobs in these supplier industries are supported by each $1 million in construction services purchased.

Materials supplier jobs

To obtain materials supply jobs per each $1 million in final demand, I sum up all rows in the column vector from the ERM, and then subtract out the direct jobs. For construction, I simply sum all nonconstruction entries in the column vector from the ERM.