November 24, 2010

A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy One

New research underlines the wisdom of being absorbed in what you do

By Jason Castro

We spend billions of dollars each year looking for happiness, hoping it might be bought, consumed, found, or flown to. Other, more contemplative cultures and traditions assure us that this is a waste of time (not to mention money). ‘Be present’ they urge. Live in the moment, and there you’ll find true contentment.

Sure enough, our most fulfilling experiences are typically those that engage us body and mind, and are unsullied by worry or regret. In these cases, a relationship between focus and happiness is easy to spot. But does this relationship hold in general, even for simple, everyday activities? Is a focused mind a happy mind? Harvard psychologists Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert decided to find out.

In a recent study published in Science, Killingsworth and Gilbert discovered that an unnervingly large fraction of our thoughts - almost half - are not related to what we’re doing. Surprisingly, we tended to be elsewhere even for casual and presumably enjoyable activities, like watching TV or having a conversation. While you might hope all this mental wandering is taking us to happier places, the data say otherwise. Just like the wise traditions teach, we’re happiest when thought and action are aligned, even if they’re only aligned to wash dishes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The ingredients of simple, everyday happiness are tough to study in the lab, and aren’t easily measured with a standard experimental battery of forced choices, eye-tracking, and questionnaires. Day to day happiness is simply too fleeting. To really study it’s causes, you need to catch people in the act of feeling good or feeling bad in real-world settings.

To do this, the researchers used a somewhat unconventional, but powerful, technique known as experience sampling. The idea behind it is simple. Interrupt people at unpredictable intervals and ask them what they’re doing, and what’s on their minds. If you do this many times a day for many days, you can start to assemble a kind of quantitative existential portrait of someone. Do this for many people, and you can find larger patterns and tendencies in human thought and behavior, allowing you to correlate moments of happiness with particular kinds of thought and action.

To sample our inner lives, the team developed an iPhone app that periodically surveyed people’s thoughts and activities. At random times throughout the day, a participant’s iPhone would chime, and present him with a brief questionnaire that asked how happy he was (on a scale from 1-100), what he was doing, and if he was thinking about what he was doing. If subjects were indeed thinking of something else, they reported whether that something else was pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant. Responses to the questions were standardized, which allowed them to be neatly summarized in a database that tracked the collective moods, actions, and musings of about 5000 total participants (a subset of 2250 people was used in the present study).

In addition to awakening us to just how much our minds wander, the study clearly showed that we’re happiest when thinking about what we’re doing. Although imagining pleasant alternatives was naturally preferable to imagining unpleasant ones, the happiest scenario was to not be imagining at all. A person who is ironing a shirt and thinking about ironing is happier than a person who is ironing and thinking about a sunny getaway.

What about the kinds of activities we do, though? Surely, the hard-partiers and world travelers among us are happier than the quiet ones who stay at home and tuck in early? Not necessarily. According to the data from the Harvard group’s study, the particular way you spend your day doesn’t tell much about how happy you are. Mental presence - the matching of thought to action - is a much better predictor of happiness.

The happy upshot of this study is that it suggests a wonderfully simple prescription for greater happiness: think about what you’re doing. But be warned that like any prescription, following it is very different from just knowing it’s good for you. In addition to the usual difficulties of breaking bad or unhelpful habits, your brain may also be wired to work against your attempts stay present.

Recent fMRI scanning studies show that even when we’re quietly at rest and following instructions to think of nothing in particular, our brains settle into a conspicuous pattern of activity that corresponds to mind-wandering. This signature ‘resting’ activity is coordinated across several widespread brain areas , and is argued by many to be evidence of a brain network that is active by default. Under this view our brains climb out of the default state when we’re bombarded with input, or facing a challenging task, but tend to slide back into it once things quiet down.

Why are our brains so intent on tuning out? One possibility is that they’re calibrated for a target level of arousal. If a task is dull and can basically be done on autopilot, the brain conjures up its own exciting alternatives and sends us off and wandering. This view is somewhat at odds with the Killingsworth and Gilbert’s findings though, since subjects wandered even on ‘engaging’ activities. Another, more speculative possibility is that wandering corresponds to some important mental housekeeping or regulatory process that we’re not conscious of. Perhaps while we check out, disparate bits of memory and experience are stitched together into a coherent narrative – our sense of self.

Of course, it’s also possible that wandering isn’t really ‘for’ anything, but rather just a byproduct of a brain in a world that doesn’t punish the occasional (or even frequent) flight of fancy. Regardless of what prompts our brains to settle into the default mode, its tendency to do so may be the kiss of death for happiness. As the authors of the paper elegantly summarize their work: “a human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind.”

On the plus side, a mind can be trained to wander less. With regular and dedicated meditation practice, you can certainly become much more present, mindful, and content. But you’d better be ready to work. The most dramatic benefits only really accrue for individuals, often monks, who have clocked many thousands of hours practicing the necessary skills (it’s not called the default state for nothing).

The next steps in this work will be fascinating to see, and we can certainly expect to see more results from the large data set collected by Killingsworth and Gilbert. It will be interesting to know, for example, how much people vary in their tendency to wander, and whether differences in wandering are associated with psychiatric ailments. If so, we may be able to tailor therapeutic interventions for people prone to certain cognitive styles that put them at risk for depression, anxiety, or other disorders.

In addition to the translational potential of this work, it will also be exciting to understand the brain networks responsible for wandering, and whether there are trigger events that send the mind into the wandering or focused state. Though wandering may be bad for happiness, it is still fascinating to wonder why we do it.

Are you a scientist? Have you recently read a peer-reviewed paper that you want to write about? Then contact Mind Matters co-editor Gareth Cook, a Pulitzer prize -winning journalist at the Boston Globe, where he edits the Sunday Ideas section. He can be reached at garethideas AT gmail.com

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Alcohol is dangerous. So is ‘alcoholic.’

How old is too old to run?

America’s graying. We need to change the way we think about age.

Harvard psychologists Matthew A. Killingsworth (right) and Daniel T. Gilbert (left) used a special “track your happiness” iPhone app to gather research. The results: We spend at least half our time thinking about something other than our immediate surroundings, and most of this daydreaming doesn’t make us happy.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Wandering mind not a happy mind

Steve Bradt

Harvard Staff Writer

About 47% of waking hours spent thinking about what isn’t going on

People spend 46.9 percent of their waking hours thinking about something other than what they’re doing, and this mind-wandering typically makes them unhappy. So says a study that used an iPhone Web app to gather 250,000 data points on subjects’ thoughts, feelings, and actions as they went about their lives.

The research, by psychologists Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert of Harvard University, is described this week in the journal Science .

“A human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind,” Killingsworth and Gilbert write. “The ability to think about what is not happening is a cognitive achievement that comes at an emotional cost.”

Unlike other animals, humans spend a lot of time thinking about what isn’t going on around them: contemplating events that happened in the past, might happen in the future, or may never happen at all. Indeed, mind-wandering appears to be the human brain’s default mode of operation.

To track this behavior, Killingsworth developed an iPhone app that contacted 2,250 volunteers at random intervals to ask how happy they were, what they were currently doing, and whether they were thinking about their current activity or about something else that was pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant.

Subjects could choose from 22 general activities, such as walking, eating, shopping, and watching television. On average, respondents reported that their minds were wandering 46.9 percent of time, and no less than 30 percent of the time during every activity except making love.

“Mind-wandering appears ubiquitous across all activities,” says Killingsworth, a doctoral student in psychology at Harvard. “This study shows that our mental lives are pervaded, to a remarkable degree, by the nonpresent.”

Killingsworth and Gilbert, a professor of psychology at Harvard, found that people were happiest when making love, exercising, or engaging in conversation. They were least happy when resting, working, or using a home computer.

“Mind-wandering is an excellent predictor of people’s happiness,” Killingsworth says. “In fact, how often our minds leave the present and where they tend to go is a better predictor of our happiness than the activities in which we are engaged.”

The researchers estimated that only 4.6 percent of a person’s happiness in a given moment was attributable to the specific activity he or she was doing, whereas a person’s mind-wandering status accounted for about 10.8 percent of his or her happiness.

Time-lag analyses conducted by the researchers suggested that their subjects’ mind-wandering was generally the cause, not the consequence, of their unhappiness.

“Many philosophical and religious traditions teach that happiness is to be found by living in the moment, and practitioners are trained to resist mind wandering and to ‘be here now,’” Killingsworth and Gilbert note in Science. “These traditions suggest that a wandering mind is an unhappy mind.”

This new research, the authors say, suggests that these traditions are right.

Killingsworth and Gilbert’s 2,250 subjects in this study ranged in age from 18 to 88, representing a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds and occupations. Seventy-four percent of study participants were American.

More than 5,000 people are now using the iPhone Web app .

Share this article

You might like.

Researcher explains the human toll of language that makes addiction feel worse

No such thing, specialist says — but when your body is trying to tell you something, listen

Experts say instead of disability, focus needs to shift to ability, health, with greater participation, economically and socially

When math is the dream

Dora Woodruff was drawn to beauty of numbers as child. Next up: Ph.D. at MIT.

Seem like Lyme disease risk is getting worse? It is.

The risk of Lyme disease has increased due to climate change and warmer temperature. A rheumatologist offers advice on how to best avoid ticks while going outdoors.

- TED Speaker

Matt Killingsworth

Why you should listen.

While doing his PhD research with Dan Gilbert at Harvard, Matt Killingsworth invented a nifty tool for investigating happiness: an iPhone app called Track Your Happiness that captured feelings in real time. (Basically, it pings you at random times and asks: How are you feeling right now, and what are you doing?) Data captured from the study became the landmark paper "A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind" ( PDF ).

As an undergrad, Killingsworth studied economics and engineering, and worked for a few years as a software product manager -- an experience during which, he says, "I began to question my assumptions about what defined success for an individual, an organization, or a society." He's now a Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholar examining such topics as "the relationship between happiness and the content of everyday experiences, the percentage of everyday experiences that are intrinsically valuable, and the degree of congruence between the causes of momentary happiness and of one’s overall satisfaction with life."

Matt Killingsworth’s TED talk

Want to be happier? Stay in the moment

More news and ideas from matt killingsworth, dear ted: “how can i be happier at work”.

Smart advice from TED speakers to help you rediscover your joy on the job

The power of daydreams: 4 studies on the surprising science of mind-wandering

[ted id=1607 width=560 height=315] What makes us happy? It’s one of the most complicated puzzles of human existence — and one that, so far, 87 speakers have explored in TEDTalks. In today’s talk, Matt Killingsworth (who studied under Dan Gilbert at Harvard) shares a novel approach to the study of happiness — an app, Track Your Happiness, […]

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Mind & Body Articles & More

Does mind-wandering make you unhappy, when are we happiest when we stay in the moment, says researcher matt killingsworth ..

What are the major causes of human happiness?

It’s an important question but one that science has yet to fully answer. We’ve learned a lot about the demographics of happiness and how it’s affected by conditions like income, education, gender, and marriage. But the scientific results are surprising: Factors like these don’t seem to have particularly strong effects. Yes, people are generally happier if they make more money rather than less, or are married instead of single, but the differences are quite modest.

Although our goals in life often revolve around these sorts of milestones, my research is driven by the idea that happiness may have more to do with the contents of our moment-to-moment experiences than with the major conditions of our lives. It certainly seems that fleeting aspects of our everyday lives—such as what we’re doing, who we’re with, and what we’re thinking about—have a big influence on our happiness, and yet these are the very factors that have been most difficult for scientists to study.

A few years ago, I came up with a way to study people’s moment-to-moment happiness in daily life on a massive scale, all over the world, something we’d never been able to do before. This took the form of trackyourhappiness.org, which uses iPhones to monitor people’s happiness in real time.

My results suggest that happiness is indeed highly sensitive to the contents of our moment-to-moment experience. And one of the most powerful predictors of happiness is something we often do without even realizing it: mind-wandering.

Be here now

As human beings, we possess a unique and powerful cognitive ability to focus our attention on something other than what is happening in the here and now. A person could be sitting in his office working on his computer, and yet he could be thinking about something else entirely: the vacation he had last month, which sandwich he’s going to buy for lunch, or worrying that he’s going bald.

This ability to focus our attention on something other than the present is really amazing. It allows us to learn and plan and reason in ways that no other species of animal can. And yet it’s not clear what the relationship is between our use of this ability and our happiness.

You’ve probably heard people suggest that you should stay focused on the present. “Be here now,” as Ram Dass advised back in 1971. Maybe, to be happy, we need to stay completely immersed and focused on our experience in the moment. Maybe this is good advice; maybe mind-wandering is a bad thing.

On the other hand, when our minds wander, they’re unconstrained. We can’t change the physical reality in front of us, but we can go anywhere in our minds. Since we know people want to be happy, maybe when our minds wander we tend to go to someplace happier than the reality that we leave behind. It would make a lot of sense. In other words, maybe the pleasures of the mind allow us to increase our happiness by mind-wandering.

Since I’m a scientist, I wanted to try to resolve this debate with some data. I collected this data using trackyourhappiness.org.

How does it work? Basically, I send people signals at random times throughout the day, and then I ask them questions about their experience at the instant just before the signal. The idea is that if we can watch how people’s happiness goes up and down over the course of the day, and try to understand how things like what people are doing, who they’re with, what they’re thinking about, and all the other factors that describe our experiences relate to those ups and downs in happiness, we might eventually be able to discover some of the major causes of human happiness.

This essay is based a 2011 TED talk by Matt Killingsworth.

In the results I’m going to describe, I will focus on people’s responses to three questions. The first was a happiness question: How do you feel? on a scale ranging from very bad to very good. Second, an activity question: What are you doing? on a list of 22 different activities including things like eating and working and watching TV. And finally a mind-wandering question: Are you thinking about something other than what you’re currently doing? People could say no (in other words, they are focused only on their current activity) or yes (they are thinking about something else). We also asked if the topic of those thoughts is pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant. Any of those yes responses are what we called mind-wandering.

We’ve been fortunate with this project to collect a lot of data, a lot more data of this kind than has ever been collected before, over 650,000 real-time reports from over 15,000 people. And it’s not just a lot of people, it’s a really diverse group, people from a wide range of ages, from 18 to late 80s, a wide range of incomes, education levels, marital statuses, and so on. They collectively represent every one of 86 occupational categories and hail from over 80 countries.

Wandering toward unhappiness

So what did we find?

First of all, people’s minds wander a lot. Forty-seven percent of the time, people are thinking about something other than what they’re currently doing. Consider that statistic next time you’re sitting in a meeting or driving down the street.

How does that rate depend on what people are doing? When we looked across 22 activities, we found a range—from a high of 65 percent when people are taking a shower or brushing their teeth, to 50 percent when they’re working, to 40 percent when they’re exercising. This went all the way down to sex, when 10 percent of the time people’s minds are wandering. In every activity other than sex, however, people were mind-wandering at least 30 percent of the time, which I think suggests that mind-wandering isn’t just frequent, it’s ubiquitous. It pervades everything that we do.

How does mind-wandering relate to happiness? We found that people are substantially less happy when their minds are wandering than when they’re not, which is unfortunate considering we do it so often. Moreover, the size of this effect is large—how often a person’s mind wanders, and what they think about when it does, is far more predictive of happiness than how much money they make, for example.

Now you might look at this result and say, “Ok, on average people are less happy when they’re mind-wandering, but surely when their minds are straying away from something that wasn’t very enjoyable to begin with, at least then mind-wandering will be beneficial for happiness.”

As it turns out, people are less happy when they’re mind-wandering no matter what they’re doing. For example, people don’t really like commuting to work very much; it’s one of their least enjoyable activities. Yet people are substantially happier when they’re focused only on their commute than when their mind is wandering off to something else. This pattern holds for every single activity we measured, including the least enjoyable. It’s amazing.

But does mind-wandering actually cause unhappiness, or is it the other way around? It could be the case that when people are unhappy, their minds wander. Maybe that’s what’s driving these results.

We’re lucky in this data in that we have many responses from each person, and so we can look and see, does mind-wandering tend to precede unhappiness, or does unhappiness tend to precede mind-wandering? This gives us some insight into the causal direction.

As it turns out, there is a strong relationship between mind-wandering now and being unhappy a short time later, consistent with the idea that mind-wandering is causing people to be unhappy. In contrast, there’s no relationship between being unhappy now and mind-wandering a short time later. Mind-wandering precedes unhappiness but unhappiness does not precede mind-wandering. In other words, mind-wandering seems likely to be a cause, and not merely a consequence, of unhappiness.

How could this be happening? I think a big part of the reason is that when our minds wander, we often think about unpleasant things: our worries, our anxieties, our regrets. These negative thoughts turn out to have a gigantic relationship to (un)happiness. Yet even when people are thinking about something they describe as neutral, they’re still considerably less happy than when they’re not mind-wandering. In fact, even when they’re thinking about something they describe as pleasant, they’re still slightly less happy than when they aren’t mind-wandering at all.

The lesson here isn’t that we should stop mind-wandering entirely—after all, our capacity to revisit the past and imagine the future is immensely useful, and some degree of mind-wandering is probably unavoidable. But these results do suggest that mind-wandering less often could substantially improve the quality of our lives. If we learn to fully engage in the present , we may be able to cope more effectively with the bad moments and draw even more enjoyment from the good ones.

About the Author

Matt Killingsworth

Matt Killingsworth, Ph.D., is a Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholar. He studies the nature and causes of human happiness, and is the creator of www.trackyourhappiness.org which uses smartphones to study happiness in real-time during everyday life. Recent research topics have included the relationship between happiness and the content of everyday experiences, the percentage of everyday experiences that are intrinsically valuable, and the degree of congruence between the causes of momentary happiness and of one's overall satisfaction with life. Matt earned his Ph.D. in psychology at Harvard University.

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

Is a Wandering Mind an Unhappy Mind? The Affective Qualities of Creativity, Volition, and Resistance

- First Online: 08 October 2022

Cite this chapter

- Nicolás González 3 ,

- Camila García-Huidobro 3 &

- Pablo Fossa 3

698 Accesses

1 Citations

In recent years, research on mind wandering has increased. Much of this scientific evidence has shown the negative effects of mind wandering, such as everyday accidents, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, concentration, and learning problems in educational processes. Although there is scientific evidence of the positive aspects of mind wandering, this is still scarce in literature. In this chapter, we propose the important role of mind wandering as an affective expression of consciousness, which extends to the processes of creativity, volition, and resistance as inter-functional connections of thought.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Agnoli, S., Vannucci, M., Pelagatti, C., & Corazza, G. E. (2018). Exploring the link between mind wandering, mindfulness, and creativity: A multidimensional approach. Creativity Research Journal, 30 (1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2018.1411423

Article Google Scholar

Alessandroni, N. (2017). Imaginación, creatividad y fantasía en Lev S. Vygotski: una aproximación a su enfoque sociocultural. Actualidades en Psicología, 31 (122), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.15517/ap.v31i122.26843

Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45 , 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to “The Social Psychology of Creativity” . Westview Press.

Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M., & Pratt, M. G. (2016). The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36 , 157–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.10.001

Andrews-Hanna, J., Irving, Z., Fox, K., Spreng, N., & Christoff, K. (2017). The neuroscience of spontaneous thought: An evolving, interdisciplinary field. In K. C. R. Fox & K. Christoff (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of spontaneous thought. (s.f) . Oxford University Press.

Awad, S. H., & Wagoner, B. (2015). Agency and creativity in the midst of social change. In C. W. Gruber, M. G. Clark, S. H. Klempe, & J. Valsiner (Eds.), Constraints of agency (pp. 229–243). Springer.

Awad, S. H., & Wagoner, B. (2017). Introducing the street art of resistance. In N. Chaudhary, P. Hviid, G. Marsico, & J. Villadsen (Eds.), Resistance in everyday life: Constructing cultural experiences (pp. 161–180). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Awad, S. H., Wagoner, B., & Glaveanu, V. (2017). The street art of resistance. In N. Chaudhary, P. Hviid, G. Marsico, & J. Villadsen (Eds.), Resistance in everyday life: Constructing cultural experiences (pp. 161–180). Springer.

Batalloso, J. M. (2019). Autoconocimiento. Sevilla . Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/40525314/AUTOCONOCIMIENTO . Accessed May 04, 2021.

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2013). Fundamentals of creativity. Educational Leadership, 70 , 10–15.

Briñol, P., Blanco, A., & De la Corte, L. (2008). Sobre la resistencia a la Psicología Social. Revista de Psicología Social, 23 (1), 107–126.

Casado, Y., Llamas-Salguero, F., & López-Fernández, V. (2015). Inteligencias múltiples, Creatividad y Lateralidad, nuevos retos en metodologías docentes enfocadas a la innovación educativa. Reidocrea, 4 (43), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.38548

Castillo-Delgado, M., Ezquerro-Cordón, A., Llamas-Salguero, F., & López-Fernández, V. (2016). Estudio neuropsicológico basado en la creatividad, las inteligencias múltiples y la función ejecutiva en el ámbito educativo. Reidocrea, 5 (2), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.39528

Chacón-Araya, Y. (2005). Una revisión crítica del concepto de creatividad. Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 5 (1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.15517/aie.v5i1.9120

Chaudhary, N., Hviid, P., Giuseppina Marsico, G., & Waag Villadsen, J. (2017). Rhythms of resistance and existence: An introduction. In N. Chaudhary, P. Hviid, G. Marsico, & J. Villadsen (Eds.), Resistance in everyday life: Constructing cultural experiences (pp. 1–9). Springer.

Christoff, K. (2012). Undirected thought: Neural determinants and correlates. Brain Research, 1428 , 51–59.

Christoff, K., Irving, Z., Fox, K., Spreng, N., & Andrews-Hanna, J. (2016). Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: A dynamic framework. Nature Reviews, 17 , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.113

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention . HarperCollins.

Delgado, Y., Delgado, Y., Giselle de la Peña, R., Rodríguez, M., & Rodríguez, R. M. (2016). Creativity in Mathematics for first-years students of Anti-Vector Fight/Control. Educación Médica Superior, 30 (2), 1–12.

Edwards-Schachter, M. (2015). Qué es la creatividad . https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4861.1043

Fernández Diaz, J. R., Llamas-Salguero, F., & Gutiérrez-Ortega, M. (2019). Creatividad: Revisión del Concepto. Reidocrea, 8 (37), 467–483. https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.58264

Fossa, P. (2017). The expressive dimension of inner speech. Psicología USP, 28 (3), 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-656420160118

Fossa, P. (In press). Lo representacional y lo expresivo: Dos funciones del lenguaje interior . Psicología: Teoría e Pesquisa.

Fossa, P., Awad, N., Ramos, F., Molina, Y., De la Puerta, S. & Cornejo, C. (2018a). Control del pensamiento, esfuerzo cognitivo y lenguaje fisionómico organísmico : Tres manifestaciones

Fossa, P., Gonzalez, N., & Cordero Di Montezemolo, F. (2018b). From inner speech to mind-wandering: Developing a theoretical model of inner mental activity trajectories. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, 53 (1), 1–25.

Fox, K., Andrews-Hanna, J., Mills, C., Dixon, M., Markovic, J., Thompson, E., & Christoff, K. (2018). Affective neuroscience of self-generated thought. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1426 (1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13740

Fox, K., & Beaty, R. (2019). Mind-wandering as creative thinking: Neural, psychological, and theoretical considerations. Behavorial Sciences, 27 , 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.10.009

Franco, C. (2006). Relación entre las variables autoconcepto y creatividad en una muestra de alumnos de educación infantil. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 8 (1), 1–16.

Gardner, H. (1993). Creating minds: An anatomy of creativity seen through the lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Ghandi . Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century . Basic Books.

Garín-Vallverdu, M. P., López-Fernández, V., & Llamas-Salguero, F. (2016). Creatividad e Inteligencias Múltiples según el género en alumnado de Educación Primaria. Reidocrea, 5 (2), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.40068

Glăveanu, V. P. (2013). Rewriting the language of creativity: The five A’s framework. Review of General Psychology, 17 (1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029528

Goldberg, E. (2018). Creativity: The human brain in the age of innovation (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press.

Gruber, H. E., & Wallace, D. (1999). The case study method and evolving systems approach for understanding unique creative people at work. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of Creativity (pp. 93–115). Cambridge University Press.

Irving, Z. C. (2016). Mind-wandering is unguided attention: Accounting for the “purposeful” wanderer. Philosophical Studies, 173 (2), 547–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-015-0506-1

Irving, Z. C., & Thompson, E. (2018). The philosophy of mind-wandering. In K. Christoff & K. Fox (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of spontaneous thought: Mind-wandering, creativity, and dreaming (s.p) . Oxford University Press.

Ivet, B., Zacatelco, F., & Acle, G. (2009). Programa de enriquecimiento de la creatividad para alumnas sobresalientes de zonas marginadas. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 7 (2), 849–876. https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v7i18.1366

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology . Dover Publications.

Kaufman, J. C., & Glăveanu, V. P. (2019). A review of creativity theories: What questions are we trying to answer? In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of creativity (2nd ed., pp. 27–43). Cambridge University Press.

Killingsworth, M., & Gilbert, D. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330 , 932. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192439

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kopp, K., & D’Mello, S. (2016). The impact of modality on mind wandering during comprehension. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 30 (1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3163

Maillet, D., Seli, P., & Schacter, D. (2017). Mind-wandering and task stimuli: Stimulus-dependent thoughts influence performance on memory tasks and are more often past- versus futureoriented. Consciousness and Cognition, 52 , 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2017.04.014

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mills, C., Raffaelli, Q., Irving, Z. C., Stan, D., & Christoff, K. (2018). Is an off-task mind a freely-moving mind? Examining the relationship between different dimensions of thought. Consciousness and Cognition, 58 , 5820–5833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2017.10.003

Molina Valencia, N. (2005). Resistencia comunitaria y transformación de conflictos. Reflexión Política, 7 (14), 70–82.

Mooneyham, B. W., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). The costs and benefits of mind-wandering: A review. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67 (1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031569

Ottaviani, C., & Couyoumdjian, A. (2013). Pros and cons of a wandering mind: A prospective study. Frontiers in Psychology, 4 (524). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00524

Piaget, J. (1923). The language and thought of the child . Routledge Classics.

Poerio, G. L., Totterdell, P., & Miles, E. (2013). Mind-wandering and negative mood: Does one thing really lead to another? Consciousness and Cognition, 22 (4), 1412–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.09.012

Ramírez Villén, V., Llamas-Salguero, F., & López-Fernández, V. (2017). Relación entre el desarrollo Neuropsicológico y la Creatividad en edades tempranas. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, 6 (1), 34–40.

Reimers, F., & Chung, C. (2016). Enseñanza y aprendizaje en el siglo XXI: metas políticas educativas, y currículo en seis países. Fondo de Cultura Económica

Ruby, R., Smallwood, J., Engen, H., & Singer, T. (2013). How self-generated thought shapes mood—the relation between mind-wandering and mood depends on the socio-temporal content of thoughts. PloS one, 8 (10), e77554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077554

Seli, P., Carriere, J. S., Thomson, D. R., Cheyne, J. A., Martens, K. A. E., & Smilek, D. (2014). Restless mind, restless body. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40 (3), 660–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035260

Seli, P., Carriere, D., & Smilek, D. (2015a). Not all mind wandering is created equal: dissociating deliberate from spontaneous mind wandering. Psychological Research, 79 , 750–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0617-x

Seli, P., Smallwood, J., Cheyne, J. A., & Smilek, D. (2015b). On the relation of mind wandering and ADHD symptomatology. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22 (3), 629–636. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0793-0

Seli, P., Risko, E., Smilek, D., & Schacter, L. (2016). Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20 (8), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.05.010

Seli, P., Ralph, B., Konishic, M., Smilek, D., & Schacter, D. (2017a). What did you have in mind? Examining the content of intentional and unintentional types of mind wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 51 , 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2017.03.007

Seli, P., Risko, E., Purdon, C., & Smilek, D. (2017b). Intrusive thoughts: Linking spontaneous mind wandering and OCD symptomatology. Psychological Research, 81 (2), 392–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-016-0756-3

Seli, P., Carriere, J. S., Wammes, J. D., Risko, E. F., Schacter, D. L., & Smilek, D. (2018). On the clock: Evidence for the rapid and strategic modulation of mind wandering. Psychological Science, 29 (8), 1247–1256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618761039

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. (2006). The restless mind. Psychological Bulletin, 132 (6), 946–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946

Smallwood, J., & O’Connor, R. C. (2011). Imprisoned by the past: Unhappy moods lead to a retrospective bias to mind wandering. Cognition and Emotion, 25 (8), 1481–1490. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.545263

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. (2015). The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66 (1), 487–518. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331

Smallwood, J., Baracaia, S., Lowe, M., & Obonsawin, M. (2003). Task unrelated thought whilst encoding information. Consciousness and Cognition, 12 (3), 452–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8100(03)00018-7

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1995). Defying the crowd . Free Press.

Unsworth, K. (2001). Unpacking creativity. Academy of Management Review, 26 (2), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/259123

Valqui Vidal, R. V. (2009). La creatividad: conceptos. Métodos y aplicaciones. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 49 (2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie4922107

Vannucci, M., & Agnoli, S. (2019). Thought dynamics: Which role for mind wandering in creativity. In R. Beghetto & G. E. Corazza (Eds.), Dynamic perspectives on creativity (pp. 245–260). Springer.

Vildoso, J. P. (2019). The transference resistances in the psychoanalytic therapy of Freud and some posfreudian conterpounts. Bricolaje . Retrieved from: https://revistas.uchile.cl/index.php/RB/article/view/54237/56976 . Accessed May 04, 2021.

Villena-González, M. (2019). Huellas de una mente errante: un terreno fértil para el florecimiento de la creatividad. In R. Videla (Ed.), Pasos para una ecología cognitiva de la educación (pp. 59–72). Editorial Universidad de la Serena.

Vygotsky, L. (1934a). Conferencias sobre psicología. En Obras Escogidas II . Machado Libros.

Vygotsky, L. (1934b). Pensamiento y Lenguaje. En Obras Escogidas II . Machado Libros.

Vygotsky, L. (1982). Sobre los sistemas psicológicos. Obras Escogidas. Pedagogía .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Psychology Department, Universidad del Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile

Nicolás González, Camila García-Huidobro & Pablo Fossa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicolás González .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

CNRS, Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon, Université Lyon 2, Lyon, France

Nadia Dario

Department of Special Needs Education, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

González, N., García-Huidobro, C., Fossa, P. (2022). Is a Wandering Mind an Unhappy Mind? The Affective Qualities of Creativity, Volition, and Resistance. In: Dario, N., Tateo, L. (eds) New Perspectives on Mind-Wandering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06955-0_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06955-0_13

Published : 08 October 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-06954-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-06955-0

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Reason Our Minds Wander

Why do people spend so many hours per day worrying, daydreaming, or focusing on anything but the present?

You probably aren’t living in the moment. Most people spend their leisure time in imaginary worlds—reading novels, watching television and movies, playing video games and so on. And when there isn’t a book or screen in front of us, our minds wander.

This seems to be the brain’s natural state. Neuroscientists describe the brain regions involved in mind wandering as the “default network,” so-called because it’s usually humming along, shutting down only when something demands conscious attention.

How does all of this mind wandering affect our happiness? In an article published in Science , Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert frame the question like this:

Many philosophical and religious traditions teach that happiness is to be found by living in the moment, and practitioners are trained to resist mind wandering and ‘to be here now.’ These traditions suggest that a wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Are they right?

Killingsworth and Gilbert used an iPhone app to collect data from over two thousand people. The app would prompt their subjects at random times to answer questions about their happiness (How are you feeling right now?”, from “very bad” to “very good”), about their ongoing activities (“What are you doing right now?”, with various options) and about whether their minds were wandering (“Are you thinking about something other than what you’re currently doing?”—and if they answered yes, they also reported whether their imagined experience was unpleasant, neutral, or pleasant.)

Consistent with previous studies, people reported mind wandering about half the time. Mind wandering was frequent for almost every activity they were involved in—the exception was “making love.” (Presumably these subjects waited until they were finished before answering the iPhone prompt.)

The novel finding was that the sages were right: People were less happy when their minds were wandering. In fact, whether or not they were mind wandering had more of an influence on their happiness than the activity they were actually involved in. As Killingsworth and Gilbert say in their title: A wandering mind is an unhappy mind.

It's not just daydreaming that makes us unhappy. Take another form of imaginative escape—the involuntary act of dreaming. The most common dream that people report isn’t anything enjoyable. It’s being chased .

Or consider the fictions we choose to engage with. Often these are positive, corresponding to events and experiences that we would enjoy in everyday life, sometimes by empathizing with an imaginary protagonist who is doing something pleasant. But many popular types of fiction correspond to experiences that are unpleasant or worse. Many of us are drawn to horror—to gruesome stories of zombies, cannibals, serial killers, torture chambers, and the like. Others prefer sadness—the young mother dying of cancer, the child with leukemia; stories of betrayal, loss, real human suffering. We pay for experiences that make us shudder and weep.

David Hume spoke of this “unaccountable pleasure” experienced by audiences of tragedies, and was savvy enough to point out that the negative emotions evoked by tragedy are a feature, not a bug: “The more they are touched and affected, the more they are delighted with the spectacle.”

It’s weird that our minds work this way. From an evolutionary perspective, you might expect that we would be driven to act in ways that have positive adaptive consequences, increasing our odds of survival and reproduction. But where’s the value in spending so much time thinking about unpleasant events that are not real?

Perhaps it’s an evolutionary accident. Our feelings can be insensitive to the difference between the real and the imagined. This is how pornography works—an image can evoke much the same response as the real thing. And so we might be captivated by horrible imagined events because thinking about actual horrible things is of obvious importance—if someone is plotting to kill you, it’s worth thinking about it, however unpleasant—and, to at least some extent, we treat the imaginary as if it were real.

But there might be something else going on. To give a sense of an alternative, think about the recent movie, “Edge of Tomorrow.”

It takes place in a near future in which the Earth is attacked by aliens. Tom Cruise plays a public relations officer with no combat experience who ends up engaged in battle, and is promptly killed. For reasons too complicated to get into here, he finds himself in a time loop, and is reborn before the battle begins, with memories of the events leading up to his death. He is able to learn from his past experience, and so he fights over and over again, getting better each time, until ultimately he defeats the aliens. The movie’s tagline is: Live. Die. Repeat.

The movie is essentially a depiction of a video game experience, where death returns you to a save point. The same idea is the theme of Groundhog Day , in which the character played by Bill Murray relives the same day, learning new skills, and ultimately becoming a better person. And it appeared earlier in the short 1904 book, “The Defence of Duffer’s Drift”, which tells the story of a young lieutenant responsible for defending a river crossing during the Boer War. His story is told as a series of dreams, beginning with a nightmare of military defeat. But in this next dream, he remembers the lessons of the last and does better, and then he dreams again, learning more, until he achieves victory in his final dream. The book was reprinted and used in military training for many years.

The experience of repeated failure is unpleasant, especially if you’re stuck in a time loop. But one can see how it would be an extraordinary power to repeatedly explore one’s options and learn from failure, with no real permanent consequences.

And this is what we do with our imagination. We use simulated worlds to prepare for the real one. In his book, “Why does tragedy give us pleasure?”, the critic A.D. Nuttall nicely summarized this view:

The human race has found a way, if not to abolish, then to defer and diminish the Darwinian treadmill of death. We send our hypotheses ahead, an expendable army, and watch them fall.

In earlier work , I called this the “safe practice” theory. It captures both the lure of the imagination and its negative tilt—we think about unhappy events because these are the events that we most need to prepare for. While we also have the capacity to conjure up enjoyable fantasies—and often do just that—we possess a grimly adaptive mental system that pushes us to think about worse-case scenarios, to obsess about failure and loss, driving us to ruminate about how we would cope if our futures went to hell. Live. Die. Repeat.

Body & Mind

Is a wandering mind an unhappy one.

Hispanic man daydreaming in office

When your teacher told you to stop daydreaming and pay attention, she might actually have helped improve your mood as well as your school performance — if the findings of a new study on mind wandering are anything to go by. The research, published in Science , shows that a wandering mind — whether you’re fantasizing about your sunny honeymoon or ruminating on a brutal divorce — is linked to low mood.

“Unlike other animals, human beings spend a lot of time thinking about what is not going on around them, contemplating events that happened in the past, might happen in the future, or will never happen at all,” the authors of the study, Harvard doctoral student Matthew Killingsworth and psychology professor Daniel Gilbert, write in the new paper. And that unique ability, they found, does not make for a happier species.

To study the relationship between mind wandering and happiness, Killingsworth and Gilbert created an iPhone app — available at Trackyourhappiness.org — which contacted participants at random times during the day to ask about their mental state and their mood. About 5,000 people responded, ranging in age from 18 to 88 and living in 83 countries around the world; Killingsworth and Daniel analyzed responses from 2,250 for the study. ( More on Time.com: Why We Conform to the Group: It Gets Your Brain High )

The app asked people three questions, related to happiness (“How are you feeling right now?”), activity (“What are you doing right now?”) and mind wandering (“Are you currently thinking about something other than what you’re currently doing?”). The results showed that people’s minds wandered a lot, regardless of what they were doing: people reported letting their minds wander 46.9% of the time, and at least 30% of the time during every activity except having sex. What’s more, people reported feeling less happy when their minds wandered than when they didn’t — even when the tasks at hand weren’t enjoyable.

“Our main result is that mind wandering on average is associated with less happiness,” says Killingsworth. “Unpleasant mind wandering in particular makes the single biggest difference in happiness [levels]. However even you if took out [negative trains of thought], mind wandering was still associated with less happiness.” ( More on TIME.com: Doodling May Help You Pay Attention )

The direction in which the mind ran off was also found to be unrelated to the person’s current situation and didn’t lift his or her mood, even when thinking about pleasant things. In other words, when people were doing fun things, their minds didn’t necessarily go to pleasant places, nor did people seem to be able to escape unpleasant tasks by drifting into a better mental spot. “When people are engaged in doing unenjoyable tasks, even when they’re thinking about pleasant things, it’s not having a positive impact. That’s surprising to me,” says Killingsworth.

On the other hand, the study did find that negative mind wandering was associated with even more unhappiness. And, in general, the researchers found that what a person was thinking about was a better predictor of happiness than whatever he or she was doing in that moment. ( More on Time.com: Spend Too Much For Those Shoes? Blame Your Genes )

Although previous research has shown that feeling down can lead to mind wandering, this study found that the reverse was true as well: mind wandering often predicted bad moods, rather than following them. “I think there’s lots of evidence that rumination and worrying can cause a lot of stress in and of themselves,” notes Alan Marlatt, co-author of Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention, who was not associated with the study. Marlatt has spent decades studying meditation and other techniques to help focus the mind to fight addictions.

Indeed, in contrast to mind wandering, being able to focus on the present is thought to boost happiness. Most meditation techniques involve learning to “be in the moment,” and numerous studies have linked meditation to greater happiness, better ability to cope with stress and pain and even improvements in physical health. “It gives you more opportunity to stand back and take a moment to choose what to do next, instead of having your mind on auto-pilot and you’re not there,” says Marlatt. The ability to call home the wandering mind, and just “take time to be where you are,” through techniques like focusing on breathing can “make a huge difference,” he says. ( More on TIME.com: Losing Focus? Studies Say Meditation May Help )

But that’s not to say that mind wandering is all bad: innovative ideas and insights often arise through free association. And being able to plan and strategize effectively require a focus on the future, not the now. “There’s no doubt that this capacity is beneficial in a variety of ways and it’s certainly very possible that a lot of creative thinking involves mind wandering,” says Killingsworth.

His research is ongoing, and Killingsworth urges interested participants to visit Trackyourhappiness.org .

“In this electronic age where everyone’s on the phone all the time and [constantly distracted], it’s interesting to use an app to maybe turn that around and ask people to be more mindful instead of just answering the next email,” says Marlatt.

More on Time.com: Why We Strive for Money Over Time — and Why It’s a Mistake How Much Happiness Can Money Buy? About $75,000 Worth Bowl Half Empty? How to Tell If Your Dog Is a Pessimist

Mind is a frequent, but not happy, wanderer: People spend nearly half their waking hours thinking about what isn’t going on around them

People spend 46.9 percent of their waking hours thinking about something other than what they're doing, and this mind-wandering typically makes them unhappy. So says a study that used an iPhone web app to gather 250,000 data points on subjects' thoughts, feelings, and actions as they went about their lives.

The research, by psychologists Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert of Harvard University, is described in the journal Science .

"A human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is an unhappy mind," Killingsworth and Gilbert write. "The ability to think about what is not happening is a cognitive achievement that comes at an emotional cost."

Unlike other animals, humans spend a lot of time thinking about what isn't going on around them: contemplating events that happened in the past, might happen in the future, or may never happen at all. Indeed, mind-wandering appears to be the human brain's default mode of operation.

To track this behavior, Killingsworth developed an iPhone web app that contacted 2,250 volunteers at random intervals to ask how happy they were, what they were currently doing, and whether they were thinking about their current activity or about something else that was pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant.

Subjects could choose from 22 general activities, such as walking, eating, shopping, and watching television. On average, respondents reported that their minds were wandering 46.9 percent of time, and no less than 30 percent of the time during every activity except making love.

"Mind-wandering appears ubiquitous across all activities," says Killingsworth, a doctoral student in psychology at Harvard. "This study shows that our mental lives are pervaded, to a remarkable degree, by the non-present."

Killingsworth and Gilbert, a professor of psychology at Harvard, found that people were happiest when making love, exercising, or engaging in conversation. They were least happy when resting, working, or using a home computer.

"Mind-wandering is an excellent predictor of people's happiness," Killingsworth says. "In fact, how often our minds leave the present and where they tend to go is a better predictor of our happiness than the activities in which we are engaged."

The researchers estimated that only 4.6 percent of a person's happiness in a given moment was attributable to the specific activity he or she was doing, whereas a person's mind-wandering status accounted for about 10.8 percent of his or her happiness.

Time-lag analyses conducted by the researchers suggested that their subjects' mind-wandering was generally the cause, not the consequence, of their unhappiness.

"Many philosophical and religious traditions teach that happiness is to be found by living in the moment, and practitioners are trained to resist mind wandering and to 'be here now,'" Killingsworth and Gilbert note in Science. "These traditions suggest that a wandering mind is an unhappy mind."

This new research, the authors say, suggests that these traditions are right.

Killingsworth and Gilbert's 2,250 subjects in this study ranged in age from 18 to 88, representing a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds and occupations. Seventy-four percent of study participants were American.

More than 5,000 people are now using the iPhone web app the researchers have developed to study happiness, which can be found at www.trackyourhappiness.org .

- Brain-Computer Interfaces

- Social Psychology

- Neural Interfaces

- Computer Programming

- Educational Technology

- Social psychology

- Web crawler

- World Wide Web

- Philosophy of mind

- Rapid eye movement

- Computer vision

- Cognitive dissonance

- Information architecture

Story Source:

Materials provided by Harvard University . Original written by Steve Bradt, Harvard Staff Writer. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Matthew A. Killingsworth, Daniel T. Gilbert. A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind . Science , 2010; 330 (6006): 932 DOI: 10.1126/science.1192439

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Anticoagulant With an On-Off Switch

- Sleep Resets Brain Connections -- At First

- Far-Reaching Effects of Exercise

- Hidden Connections Between Brain and Body

- Novel Genetic Plant Regeneration Approach

- Early Human Occupation of China

- Journey of Inhaled Plastic Particle Pollution

- Earth-Like Environment On Ancient Mars

- A 'Cosmic Glitch' in Gravity

- Time Zones Strongly Influence NBA Results

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

When the Mind Wanders, Happiness Also Strays

By John Tierney

- Nov. 15, 2010

A quick experiment. Before proceeding to the next paragraph, let your mind wander wherever it wants to go. Close your eyes for a few seconds, starting ... now.

And now, welcome back for the hypothesis of our experiment: Wherever your mind went — the South Seas, your job, your lunch, your unpaid bills — that daydreaming is not likely to make you as happy as focusing intensely on the rest of this column will.

I’m not sure I believe this prediction, but I can assure you it is based on an enormous amount of daydreaming cataloged in the current issue of Science . Using an iPhone app called trackyourhappiness , psychologists at Harvard contacted people around the world at random intervals to ask how they were feeling, what they were doing and what they were thinking.

The least surprising finding, based on a quarter-million responses from more than 2,200 people, was that the happiest people in the world were the ones in the midst of enjoying sex. Or at least they were enjoying it until the iPhone interrupted.

The researchers are not sure how many of them stopped to pick up the phone and how many waited until afterward to respond. Nor, unfortunately, is there any way to gauge what thoughts — happy, unhappy, murderous — went through their partners’ minds when they tried to resume.

When asked to rate their feelings on a scale of 0 to 100, with 100 being “very good,” the people having sex gave an average rating of 90. That was a good 15 points higher than the next-best activity, exercising, which was followed closely by conversation, listening to music, taking a walk, eating, praying and meditating, cooking, shopping, taking care of one’s children and reading. Near the bottom of the list were personal grooming, commuting and working.

When asked their thoughts, the people in flagrante were models of concentration: only 10 percent of the time did their thoughts stray from their endeavors. But when people were doing anything else, their minds wandered at least 30 percent of the time, and as much as 65 percent of the time (recorded during moments of personal grooming, clearly a less than scintillating enterprise).

On average throughout all the quarter-million responses, minds were wandering 47 percent of the time. That figure surprised the researchers, Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert .

“I find it kind of weird now to look down a crowded street and realize that half the people aren’t really there,” Dr. Gilbert says.

You might suppose that if people’s minds wander while they’re having fun, then those stray thoughts are liable to be about something pleasant — and that was indeed the case with those happy campers having sex. But for the other 99.5 percent of the people, there was no correlation between the joy of the activity and the pleasantness of their thoughts.

“Even if you’re doing something that’s really enjoyable,” Mr. Killingsworth says, “that doesn’t seem to protect against negative thoughts. The rate of mind-wandering is lower for more enjoyable activities, but when people wander they are just as likely to wander toward negative thoughts.”

Whatever people were doing, whether it was having sex or reading or shopping, they tended to be happier if they focused on the activity instead of thinking about something else. In fact, whether and where their minds wandered was a better predictor of happiness than what they were doing.

“If you ask people to imagine winning the lottery,” Dr. Gilbert says, “they typically talk about the things they would do — ‘I’d go to Italy, I’d buy a boat, I’d lay on the beach’ — and they rarely mention the things they would think . But our data suggest that the location of the body is much less important than the location of the mind, and that the former has surprisingly little influence on the latter. The heart goes where the head takes it, and neither cares much about the whereabouts of the feet.”

Still, even if people are less happy when their minds wander, which causes which? Could the mind-wandering be a consequence rather than a cause of unhappiness?

To investigate cause and effect, the Harvard psychologists compared each person’s moods and thoughts as the day went on. They found that if someone’s mind wandered at, say, 10 in the morning, then at 10:15 that person was likely to be less happy than at 10 , perhaps because of those stray thoughts. But if people were in a bad mood at 10, they weren’t more likely to be worrying or daydreaming at 10:15.

“We see evidence for mind-wandering causing unhappiness, but no evidence for unhappiness causing mind-wandering,” Mr. Killingsworth says.

This result may disappoint daydreamers, but it’s in keeping with the religious and philosophical admonitions to “Be Here Now,” as the yogi Ram Dass titled his 1971 book. The phrase later became the title of a George Harrison song warning that “a mind that likes to wander ’round the corner is an unwise mind.”

What psychologists call “flow” — immersing your mind fully in activity — has long been advocated by nonpsychologists. “Life is not long,” Samuel Johnson said, “and too much of it must not pass in idle deliberation how it shall be spent.” Henry Ford was more blunt: “Idleness warps the mind.” The iPhone results jibe nicely with one of the favorite sayings of William F. Buckley Jr.: “Industry is the enemy of melancholy.”

Alternatively, you could interpret the iPhone data as support for the philosophical dictum of Bobby McFerrin : “Don’t worry, be happy.” The unhappiness produced by mind-wandering was largely a result of the episodes involving “unpleasant” topics. Such stray thoughts made people more miserable than commuting or working or any other activity.

But the people having stray thoughts on “neutral” topics ranked only a little below the overall average in happiness. And the ones daydreaming about “pleasant” topics were actually a bit above the average, although not quite as happy as the people whose minds were not wandering.

There are times, of course, when unpleasant thoughts are the most useful thoughts. “Happiness in the moment is not the only reason to do something,” says Jonathan Schooler , a psychologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His research has shown that mind-wandering can lead people to creative solutions of problems, which could make them happier in the long term.

Over the several months of the iPhone study, though, the more frequent mind-wanderers remained less happy than the rest, and the moral — at least for the short-term — seems to be: you stray, you pay. So if you’ve been able to stay focused to the end of this column, perhaps you’re happier than when you daydreamed at the beginning. If not, you can go back to daydreaming starting...now.

Or you could try focusing on something else that is now, at long last, scientifically guaranteed to improve your mood. Just make sure you turn the phone off.

Meditation Helps Keep Our Wandering Minds in Line

Wandering minds are unhappy minds; fortunately, meditation decreases wandering..

Posted December 21, 2011

We spend a lot of time thinking about what is NOT happening, contemplating events that occurred in the past or that might happen in the future. Indeed, this sort of "mind-wandering" is thought to be the default operating mode of our brains.

Although being able to think about what isn't going on around us can help us learn from the past and productively reason about the future, it comes at an emotional cost. Simply put, a wandering mind is an unhappy mind. People report being less happy when their minds are wandering compared to when they are not. But, a new study published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that there is something we can do to decrease the mind-wandering: it's meditation.

As it happens, experienced meditators report less mind wandering while meditating than people without any meditation experience. And, even when meditators are simply asked to not think of anything in particular, their brains also do a better job of keeping them present-focused.

To explore the power of meditation in curbing mind-wandering, a group of experienced meditators and a group of meditation novices were asked to perform several different types of meditations while their brains were scanned using fMRI. The experienced meditators had over 10 years and 10,000 hours of mindfulness meditation experience under their belts. The meditation novices had none. Importantly, each non-meditator was selected to match a meditator in terms of their country of origin, primary language, sex , age, race, education , and employment status. The idea was to compare folks who were pretty similar in all aspects, except for their meditation experience.

Mindfulness plays a central role in many forms of meditation and includes two main components: (i) maintaining attention on your immediate experience and (ii) maintaining an attitude of acceptance toward this experience. Because of this present-centered focus, the researchers had a hunch that people who practiced mindfulness might be better at staying in the present - and not having their minds wander - during their meditative practice. While their brains were scanned, people performed three standardized meditation techniques commonly taught within the mindfulness tradition: Concentration, Loving-Kindness, and Choiceless Awareness. Here are the instructions used for each one:

Concentration: "Please pay attention to the physical sensation of the breath wherever you feel it most strongly in the body. Follow the natural and spontaneous movement of the breath, not trying to change it in any way. Just pay attention to it. If you find that your attention has wandered to something else, gently but firmly bring it back to the physical sensation of the breath."

Loving-Kindness: "Please think of a time when you genuinely wished someone well. Using this feeling as a focus, silently wish all beings well, by repeating a few short phrases of your choosing over and over. For example: May all beings be happy, may all beings be healthy, may all beings be safe from harm."

Choiceless Awareness: "Please pay attention to whatever comes into your awareness, whether it is a thought, emotion , or body sensation. Just follow it until something else comes into your awareness, not trying to hold onto it or change it in any way. When something else comes into your awareness, just pay attention to it until the next thing comes along"

While meditating, brain areas commonly active when our minds wander were relatively less active in experienced meditators compared to controls. But, most interesting, even when the meditators weren't instructed to do any sort of meditation at all their brains looked different. At rest, meditators showed stronger cross-talk among brain areas typically involved in mind wandering and brain areas involved in working memory and self control . As I have blogged about before , working memory helps keep what we want in mind and distracting information out. The meditators seemed to have developed the ability to automatically activate working memory when mind wandering threatened to take over, allowing them to control and dampen thoughts that might take them astray. Meditation practices appear to transform people's experience when they are not doing anything at all into one that resembles a meditative state - a more present-centered state of mind.

Of course, it is possible that the meditation experts didn't learn to curb their wandering mind through meditation, but rather were attracted to meditation in the first place because their minds tended not to wander. However, a host of recent work showing that meditation changes the brain points to its potentially powerful influence on mind wandering.

Mind wandering isn't just a common activity, it's thought to occur in roughly 50% of our awake life. Many philosophical, contemplative and religious practices teach us that happiness comes from living "in the moment." One way this can be accomplished may be through meditative practices that train our brains to rein in our wandering minds.

For more on the links between body and mind, check out my book Choke !

Follow me on Twitter !

Sian Beilock, Ph.D. , is a cognitive scientist and the President of Barnard College at Columbia University. She's an expert on why people choke under pressure and how to fix it.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

A wandering mind is an unhappy mind

Affiliation.

- 1 Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 21071660

- DOI: 10.1126/science.1192439

We developed a smartphone technology to sample people's ongoing thoughts, feelings, and actions and found (i) that people are thinking about what is not happening almost as often as they are thinking about what is and (ii) found that doing so typically makes them unhappy.

- Aged, 80 and over

- Middle Aged

- Regression Analysis

- Young Adult

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘Like a film in my mind’: hyperphantasia and the quest to understand vivid imaginations

Research that aims to explain why some people experience intense visual imagery could lead to a better understanding of creativity and some mental disorders

W illiam Blake’s imagination is thought to have burned with such intensity that, when creating his great artworks, he needed little reference to the physical world. While drawing historical or mythical figures, for instance, he would wait until the “spirit” appeared in his mind’s eye. The visions were apparently so detailed that Blake could sketch as if a real person were sitting before him.

Like human models, these imaginary figures could sometimes act temperamentally. According to Blake biographer John Higgs , the artist could become frustrated when the object of his inner gaze casually changed posture or left the scene entirely. “I can’t go on, it is gone! I must wait till it returns,” Blake would declaim.

Such intense and detailed imaginations are thought to reflect a condition known as hyperphantasia, and it may not be nearly as rare as we once thought, with as many as one in 30 people reporting incredibly vivid mind’s eyes.

Just consider the experiences of Mats Holm, a Norwegian hyperphantasic living in Stockholm. “I can essentially zoom out and see the entire city around me, and I can fly around inside that map of it,” Holm tells me. “I have a second space in my mind where I can create any location.”

This once neglected form of neurodiversity is now a topic of scientific study, which could lead to insights into everything from creative inspiration to mental illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder and psychosis.

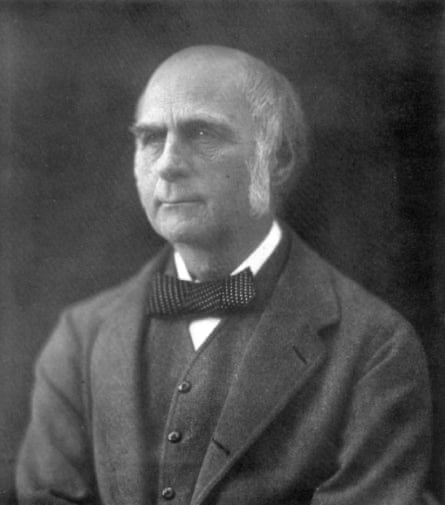

Francis Galton – better known as a racist and the “father of eugenics” – was the first scientist to recognise the enormous variation in people’s visual imagery. In 1880, he asked participants to rate the “illumination, definition and colouring of your breakfast table as you sat down to it this morning”. Some people reported being completely unable to produce an image in the mind’s eye, while others – including his cousin Charles Darwin – could picture it extraordinarily clearly.

“Some objects quite defined. A slice of cold beef, some grapes and a pear, the state of my plate when I had finished and a few other objects are as distinct as if I had photos before me,” Darwin wrote to Galton.

Unfortunately, Galton’s findings failed to fire the imagination of scientists at the time. “The psychology of visual imagery was a very big topic, but the existence of people at the extremes somehow disappeared from view,” says Prof Adam Zeman at Exeter University. It would take more than a century for psychologists such as Zeman to take up where Galton left off.

Even then, much of the initial research focused on the poorer end of the spectrum – people with aphantasia , who claim to lack a mind’s eye. Within the past five years, however, interest in hyperphantasia has started to grow, and it is now a thriving area of research.

To identify where people lie on the spectrum, researchers often use the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ), which asks participants to visualise a series of 16 scenarios, such as “the sun rising above the horizon into a hazy sky” and then report on the level of detail that they “see” in a five-point scale. You can try it for yourself. When you picture that sunrise, which of the following statements best describes your experience?

1. No image at all, you only “know” that you are thinking of the object 2. Vague and dim 3. Moderately clear and lively 4. Clear and reasonably vivid 5. Perfectly clear and as vivid as real seeing

The final score is the sum of all 16 responses, with a maximum of 80 points. In large surveys, most people score around 55 to 60 . Around 1% score just 16; they are considered to have extreme aphantasia; 3%, meanwhile, achieve a perfect score of 80, which is extreme hyperphantasia.

The VVIQ is a relatively blunt tool, but Reshanne Reeder, a lecturer at Liverpool University, has now conducted a series of in-depth interviews with hyperphantasic people – research that helps to delineate the peculiarities of their inner lives. “As you talk to them, you start to realise that this is a very different experience from most people’s experience,” she says. “It’s extremely immersive, and their imagery affects them very emotionally.”

Some people with hyperphantasia are able to merge their mental imagery with their view of the world around them. Reeder asked participants to hold out a hand and then imagine an apple sitting in their palm. Most people feel that the scene in front of their eyes is distinct from that inside their heads. “But a lot of people with hyperphantasia – about 75% – can actually see an apple in the hand in front of them. And they can even feel its weight.”

As you might expect, these visual abilities can influence career choices. “Aphantasia does seem to bias people to work in sciences, maths or IT – those Stem professions – whereas hyperphantasia nudges people to work in what are traditionally called creative professions,” says Zeman. “Though there are many exceptions.”

Reeder recalls one participant who uses her hyperphantasia to fuel her writing. “She said she doesn’t even have to think about the stories that she’s writing, because she can see the characters right in front of her, acting out their parts,” Reeder recalls.

H yperphantasia can also affect people’s consumption of art. Novels, for example, become a cinematic experience. “For me, the story is like a film in my mind,” says Geraldine van Heemstra , an artist based in London. Holm offers the same description. “When I listen to an audiobook, I’m running a movie in my head.”