Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Sundowning: late-day confusion, i've heard that sundowning may happen with dementia. what is sundowning and how is it treated.

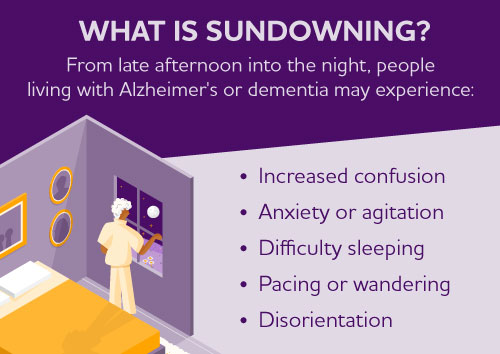

The term "sundowning" refers to a state of confusion that occurs in the late afternoon and lasts into the night. Sundowning can cause various behaviors, such as confusion, anxiety, aggression or ignoring directions. Sundowning also can lead to pacing or wandering.

Sundowning isn't a disease. It's a group of symptoms that occurs at a specific time of the day. These symptoms may affect people with Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia. The exact cause of sundowning is not known.

Factors that may worsen late-day confusion

- Spending a day in a place that's not familiar.

- Low lighting.

- Increased shadows.

- Disruption of the body's "internal clock."

- Trouble separating reality from dreams.

- Being hungry or thirsty.

- Presence of an infection, such as a urinary tract infection.

- Being bored or in pain.

- Depression.

Tips for reducing sundowning

- Keep a predictable routine for bedtime, waking, meals and activities.

- Plan for activities and exposure to light during the day to support nighttime sleepiness.

- Limit daytime napping.

- Limit caffeine and sugar to morning hours.

- Turn on a night light to reduce agitation that occurs when surroundings are dark or not familiar.

- In the evening, try to reduce background noise and stimulating activities. This includes TV viewing, which can sometimes be upsetting.

- In a strange or not familiar setting, bring familiar items, such as photographs. They can create a more relaxed setting.

- In the evening, play familiar, gentle music or relaxing sounds of nature, such as the sound of waves.

Some research suggests that a low dose of melatonin may help ease sundowning. Melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone that induces sleepiness. It can help when taken alone or in combination with exposure to bright light during the day.

It's possible that a medicine side effect, pain, depression or other condition could contribute to sundowning. Talk with a healthcare professional if you suspect that a condition might be making someone's sundowning worse. A urinary tract infection or sleep apnea could be contributing to sundowning, especially if it comes on quickly.

Jonathan Graff-Radford, M.D.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Alzheimer's prevention: Does it exist?

- Todd WD. Potential pathways for circadian dysfunction and sundowning-related behavioral aggression in Alzheimer's disease and related dementia. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2020; doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00910.

- Sleep issues and sundowning. Alzheimer's Association. http://www.alz.org/care/alzheimers-dementia-sleep-issues-sundowning.asp. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Managing personality and behavior changes in Alzheimer's. National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/managing-personality-and-behavior-changes-alzheimers. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Francis J. Delirium and confusional states: Prevention, treatment, and prognosis. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Graff-Radford J (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. April 7, 2022.

- Tips for coping with sundowning. National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/tips-coping-sundowning. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Reiter RJ, et al. Brain washing and neural health: Role of age, sleep and the cerebrospinal fluid melatonin rhythm. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2023; doi:10.1007/s00018-023-04736-5.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Alzheimer's Disease

- Assortment of Products for Independent Living from Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Day to Day: Living With Dementia

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Healthy Aging

- Give today to find Alzheimer's cures for tomorrow

- Alzheimer's sleep problems

- Alzheimer's: New treatments

- Alzheimer's 101

- Understanding the difference between dementia types

- Alzheimer's disease

- Alzheimer's drugs

- Alzheimer's genes

- Alzheimer's stages

- Antidepressant withdrawal: Is there such a thing?

- Antidepressants and alcohol: What's the concern?

- Antidepressants and weight gain: What causes it?

- Antidepressants: Can they stop working?

- Antidepressants: Side effects

- Antidepressants: Selecting one that's right for you

- Antidepressants: Which cause the fewest sexual side effects?

- Anxiety disorders

- Atypical antidepressants

- Caregiver stress

- Clinical depression: What does that mean?

- Corticobasal degeneration (corticobasal syndrome)

- Depression and anxiety: Can I have both?

- Depression, anxiety and exercise

- What is depression? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

- Depression in women: Understanding the gender gap

- Depression (major depressive disorder)

- Depression: Supporting a family member or friend

- Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Did the definition of Alzheimer's disease change?

- How your brain works

- Intermittent fasting

- Lecanemab for Alzheimer's disease

- Male depression: Understanding the issues

- MAOIs and diet: Is it necessary to restrict tyramine?

- Marijuana and depression

- Mayo Clinic Minute: 3 tips to reduce your risk of Alzheimer's disease

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Alzheimer's disease risk and lifestyle

- Mayo Clinic Minute: New definition of Alzheimer's changes

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Women and Alzheimer's Disease

- Memory loss: When to seek help

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- Natural remedies for depression: Are they effective?

- Nervous breakdown: What does it mean?

- New Alzheimers Research

- Pain and depression: Is there a link?

- Phantosmia: What causes olfactory hallucinations?

- Positron emission tomography scan

- Posterior cortical atrophy

- Seeing inside the heart with MRI

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Treatment-resistant depression

- Tricyclic antidepressants and tetracyclic antidepressants

- Video: Alzheimer's drug shows early promise

- Vitamin B-12 and depression

- Young-onset Alzheimer's

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Sundowning Late-day confusion

Let’s celebrate our doctors!

Join us in celebrating and honoring Mayo Clinic physicians on March 30th for National Doctor’s Day.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Alzheimers Dement (Amst)

What do we know about strategies to manage dementia-related wandering? A scoping review

Noelannah a. neubauer.

a Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Peyman Azad-Khaneghah

Antonio miguel-cruz.

b School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia

Associated Data

Three of five persons with dementia will wander, raising concern as to how it can be managed effectively. Wander-management strategies comprise a range of interventions for different environments. Although technological interventions may help in the management of wandering, no review has exhaustively searched what types of high- and low-technological solutions are being used to reduce the risks of wandering. In this article, we perform a review of gray and scholarly literature that examines the range and extent of high- and low-tech strategies used to manage wandering behavior in persons with dementia. We conclude that although effectiveness of 49 interventions and usability of 13 interventions were clinically tested, most were evaluated in institutional or laboratory settings, few addressed ethical issues, and the overall level of scientific evidence from these outcomes was low. Based on this review, we provide guidelines and recommendations for future research in this field.

- • Twenty categories of high and low-tech wander-management strategies were identified.

- • Most strategies were only evaluated in institutional or laboratory settings.

- • Overall level of scientific evidence from the outcomes of these strategies was low.

- • Research is required to demonstrate the efficacy of high- and low-tech strategies.

1. Introduction

The rates of cognitive impairment are on the rise worldwide as our world population ages. In 2016, 46.6 million people globally were living with dementia, and this number is projected to increase to 75 million by 2030 [1] . As a result, the already high economic burden of $818 billion in 2015 has been estimated to have increased to $1 trillion by 2018. These staggering numbers have led to the establishment of more than 30 national dementia strategies worldwide as nations begin to work together to transform dementia care and support [2] .

One significant concern for persons with dementia and their family caregivers is becoming lost when alone or in unfamiliar environments [3] , [4] . This behavior is often indicative of wandering. Wandering has been defined as “a syndrome of dementia-related locomotion behavior having repetitive, frequent, temporally disoriented nature that is manifested in lapping, random, and/or pacing patterns some of which are associated with eloping, eloping attempts, or getting lost unless accompanied” [5] . It can be either an aimless or purposeful behavior [5] , and its severity can be affected by rhythm disturbances [6] , spatial disorientation and visual-perceptual deficits [7] , physical [8] and social [9] environments, or changes in personality and behavior patterns [10] . A more recent definition of wandering also includes critical wandering, the type of wandering that results in older adults to elope with no orientation to time and place. Indeed, critical wandering is what exposes persons with dementia to the potential dangers that is of concern to caregivers [11] .

More than 60% of persons with dementia will wander. The consequences of wandering vary from minor injuries [12] , to high search and rescue costs and death [13] . If not found within 24 hours, up to half of those who wander and get lost will suffer serious injury or death [14] . Wandering behavior also significantly impacts the care and economic burden of family caregivers. For example, caregivers have been found to experience increases in emotional distress and potential civil tort claims and regulatory penalties [15] . The severity of these outcomes has gained attention from caregivers and first responders alike [16] and raises questions about how the adverse outcomes associated with wandering can be managed, and whether managing this behavior can have an influence on improving the stressors that result from caring for a person with dementia [17] .

Early interventions to manage wandering included physical restraints and medications [18] ; however, use of such strategies have been in decline due to unwanted side effects [19] and negative consequences such as poor physical and social functioning [20] . High tech strategies, such as wearable global positioning system (GPS)–enabled devices [21] , and low-tech strategies, such as visual barriers [22] , offer options for mitigating risks while allowing a person with dementia with a degree of autonomy. These strategies may therefore be a preferred approach over restraints and medications [23] . Wander-management technologies may extend the time a person with dementia can live in a community and provide peace of mind to caregivers [21] , [22] , [24] . Although such strategies are more available to consumers, only one review [25] has been conducted to examine what existing interventions for wandering are being used, and whether their effectiveness has been tested in laboratory or community settings. This review, however, only included high-tech solutions, excluding several key strategies, such as door murals and distractions, which may also help with managing this behavior. Although that review presents state of the evidence to support these interventions, it excluded potential vital reviews and studies that fall outside of this focus, limiting the scope of all available solutions within the scholarly and gray literature.

The current review serves as an extension from Neubauer et al. [25] where only high-tech solutions used to manage dementia-related wandering behavior, and only studies evaluating their usability or effectiveness were included. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to identify the range and extent of all wander-management strategies, their product readiness level, and all associated outcomes. This information provides evidence for caregivers and clinicians when they select strategies to manage wandering in persons living with dementia.

2. Methodology

2.1. design.

This is a scoping literature review based on Daudt, van Mossel, and Scott's (2013) [26] modification of Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) [27] methodology. The original Arksey and O'Malley's methodology [27] includes six steps: (1) determine the research question; (2) identify the applicable studies; (3) study selection; (4) chart data; (5) collect, summarize, and report the results; and (6) consultation exercise (optional). Daudt, van Mossel, and Scott's (2013) [26] modification of this methodology involves an interprofessional team in step (2), and in step (3) uses a three-tiered approach to cross-check and select the articles.

2.2. Data sources and search strategy

We examined peer-reviewed and gray literature published between January 1990 and November 2017. Peer-reviewed literature studies were searched in six databases: EMBASE, CINAHL, Ovid Medline, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Scopus. These databases were searched using the following terms identified in the title, abstract, or key words: (physical barrier* OR barrier* OR lock* OR low tech* OR nonpharmacological OR therap* OR exercise OR distraction OR pet therap* OR home modification* OR door mural* or signage OR identification information OR ID card* OR bracelet* OR jewelry OR technolog* OR gerontechnology OR telemonitoring OR telesurveillance OR telehealth OR assistive technology OR GPS OR sensor* OR mobile device OR application OR apps OR radio frequency telemetry OR radio frequency identification OR tracking OR surveillance OR alarms OR tagging OR electronic OR restraints) AND (wander* OR walk* OR sundowning OR escape OR restlessness OR pacing OR exit* OR missing OR stay OR benevolent wandering OR critical wandering OR non-critical wandering) AND (dementia OR Alzheimer's Disease OR cognitive disorders). Gray literature was searched in eight databases: Google, CADTH grey matters, Institute of Health Economics, Clinicaltrials.gov , The University of Alberta Grey Literature Collection, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, National Guidelines Clearinghouse, and Health on the NET Foundation were searched for strategies developed to address wandering in persons with dementia—(dementia) AND (wander* OR elope OR sundowning OR critical wandering OR benevolent wandering OR non-critical wandering) (nonpharmacological OR therap* OR exercise OR distraction OR low tech* OR home modification OR technology OR tech* OR GPS OR RFID OR mobile applications OR iOS OR android OR wifi) ( Appendix A ).

2.3. Studies selection process

Articles were exported to a reference manager where duplicate articles were excluded. Two authors (N.A.N. and P.A.-K.) first screened the titles and abstracts, reviewed the full text of all potential articles, and extracted the data ( Fig. 1 ). Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Where disagreements were unresolved, the third reviewer (A.M.C.) provided input. To determine agreement between raters, 20% of the selected articles were extracted and compared. The level of agreement between the raters was high, that is, average agreement for abstracts 96% (298/310) (average κ score of 0.87, P < .000), and 97% (198/204) average agreement for full papers (overall κ score of 0.91, P < .000). For included articles, reviewers first extracted author initials, citation, and whether the study was eligible for review. If a study was considered ineligible for data extraction, the reason for exclusion was reported ( Fig. 1 ).

Scholarly reviewed literature article search results.

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

- a. address wander-management strategies in the home or supportive care environments for persons with dementia or cognitive decline regardless of whether it was embedded in an environment, was worn, or was implemented as a form of therapy.

- b. address critical or noncritical wandering in older adults with dementia.

- c. include strategies that support independence and address outcomes associated with wandering, regardless of level of development.

- 2. Clinically oriented studies that included only persons with dementia over age 50 years.

- 3. Studies published in any language and available in full text in peer-reviewed journals or conference proceedings from electronic abstract systems.

- 4. Studies that used any type of study design or methodology, with positive or negative results.

- 5. Studies that used lower and higher complexity technologies for wander management such as GPS and door murals.

- 6. Studies published in books or book chapters and conference proceedings.

- 7. For gray literature: were websites suggesting or selling strategies to address dementia-related wandering.

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

- 1. Abstracts or studies that were not available.

- 2. Publications that did not provide adequate information for categorizing the study (e.g., participant characteristics).

2.4. Bias control

The procedure of Neubauer et al. [25] was followed to address bias. By including any language, multiple databases, and data types, we conducted a thorough search, to achieve a high level of sensitivity [28] . Inclusion of studies with positive and negative results addressed publication bias [29] . Inclusion of studies registered in electronic abstract systems served as the first “ quality filter ” and ensured a degree of scientific level of conceptual methodological rigor [30] . Studies published before 1990 were not included because most development of wander-management strategies occurred later [17] , [31] . The use of two pairs of raters during the selection for relevant articles, and a third and fourth rater when there was disagreement, minimized rater-bias that may have arisen from the subjective nature of applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.5. Publications review and data abstraction

Peer-reviewed articles were examined for the following attributes: features of wander-management strategies (i.e., strategy type, specifications, cost, product readiness level) and characteristics of research (i.e., clinical implications, sample size, participant characteristics, level of clinical evidence of outcomes). Gray literature was reviewed for features of wander-management strategies (i.e., strategy type, specifications, cost, device features). Two raters individually extracted data from articles.

2.5.1. Features of wander-management strategies

- (a) Strategy type. Refers to the name and strategy used to manage wandering. Primary categories identified include high tech [32] (e.g., locating, alarms/surveillance, wandering detection, wayfinding belt, distraction/redirection, and locks/barriers) and low tech [32] (e.g., exercise, distraction/redirection, locks/barriers, physical restraints, community, signage, wayfinding, supervision, education, and other).

- (b) Product readiness level (PRL). Assesses the maturity of evolving products during their development. We used the PRL [33] in which nine levels are used and ranged from PRL1 (basic principles observed) to PRL9 (actual system proven in operational environment).

2.5.2. Characteristics of research conducted in wander-management strategies

- (a) Type of study, design of the study, level of clinical evidence, and outcomes in the studies regarding wander-management strategies. Studies were classified into four types, including strategy- and clinical-oriented studies, usability, program-oriented, review, or a combination of them. Study design was categorized using the McMaster assessment of study appraisal [34] , [35] . An adaptation of the modified Sackett criteria proposed by Teasell et al., (2013) [36] was used to determine the level of evidence provided by the clinical-oriented studies. Using this criterion, raters assigned a level of evidence for a given technological intervention based on a seven-level scale. Quality of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was measured by the Physiotherapy Evidence Database ( PEDro ) scale [37] . The PEDro scale has 11 criteria, 10 being the maximum score that a trial can achieve. Scores of 9–10 are considered “excellent” quality; 6–8 indicates “good” quality; 4–5 are “fair” quality; and below 4 is “poor” quality [38] . As the field of wander-management technologies is diverse, we assessed the levels of evidence across three device categories: mobile locator, sensor and alarm, and wayfinding. Data on sample size, experiment length, study strategy (i.e., clinical, usability, combined), study design (i.e., qualitative or quantitative research method), main outcomes of the study, and data collection location (i.e., home, community, facility) were collected.

- (b) Ethical concern associated with the implementation of the wander-management strategy. Refers to the ethical concerns that were addressed regarding the implementation or use of the wander-management strategy. Examples of concerns include but not limited to protecting privacy, dignity, and autonomy of the person with dementia.

2.6. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted by one person (N.A.N.). Due to the diversity of the included articles, a qualitative approach was used, where content analysis was performed on the extracted data highlighted (in bold) previously. Descriptive statistics (i.e., averages and standard deviations [SDs]) were calculated for diversity of the technology specifications, strategy cost, and PRL across the included wander-management strategies, in addition to participant age, number of participants from the included studies, and study length.

The initial search identified 4096 peer-reviewed studies; 118 studies were included in the data-abstraction phase and final analysis (2.9%, 118/4096) ( Fig. 1 ). Most studies (68.6%, 59/86) were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria 1a, 1b, 1c, or all three. Other reasons for exclusion from the final data-abstraction phase were that studies were not available (31.4%, 27/86).

For the gray literature, 130 strategies from 44 commercial websites, 1 dissertation website, 5 self-help websites, 8 Alzheimer's-specific websites, and 1 online magazine were included in the data-abstraction phase and final analysis. All met inclusion criteria (7), that is, were websites suggesting or selling strategies to address dementia-related wandering.

Studies containing high-tech–only strategies were characterized by low journal impact factor (i.e., Source Normalized Impact per Paper mean 0.94, SD 0.59; 95% confidence interval [0.79, 1.08]) and were published in journals located in Q1 (13 studies), Q2 (16 studies), Q3 (5 studies), and Q4 (6 studies) journal quartile per SCImago Journal Rank classification [39] . Studies containing low-tech–only strategies were characterized by low journal impact factor (i.e., Source Normalized Impact per Paper mean 0.99, SD 0.51; 95% confidence interval [0.84, 1.14]) and were published in journals located in Q1 (19 studies), Q2 (16 studies), Q3 (6 studies), and Q4 (2 studies) journal quartile per SCImago Journal Rank classification [39] . Studies containing both high- and low-tech strategies were characterized by low journal impact factor (i.e., Source Normalized Impact per Paper mean 0.99, SD 0.82; 95% confidence interval [0.58, 1.40]) and were published in journals located in Q1 (4 studies), Q2 (7 studies), and Q3 (1 studies) journal quartile per SCImago Journal Rank classification [39] .

Regarding design [34] , [35] , seven high-tech studies were of qualitative design [phenomenology (4) and grounded theory (3)], 21 were of quantitative design [cross-sectional design (10), single-case design (4), case study (3), before-after design (1), randomized controlled trial (1), randomized pre-post (1), and descriptive (1)], and 9 were reviews [systematic review (4) and other review (5)]. Low-tech strategies included two studies that were of qualitative design [grounded theory (2)], 14 were of quantitative design [cross-sectional design (4), case study (4), single-case design (2), retrospective (1), pretest-posttest (1), ABA descriptive design (1), and randomized controlled trail (1)], and 17 were reviews [systematic review (10), Cochrane review (1), and other review (6)]. Publications containing both high- and low-tech strategies included two studies that were of qualitative design [phenomenology (2)], 4 were of quantitative design [cross-sectional design (1), single-case design (1), randomized controlled trail (1), and case study (1)], and 4 were reviews [systematic review (2), Cochrane review (1), and other review (1)] ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

Positive and negative outcomes per type of strategy (high tech vs. low tech) (n = 118) of scholarly literature

NOTE. Three of 61 high-tech, 8/42 low-tech, and 2/15 articles that contained both high- and low-tech strategies did not evaluate the effectiveness of wander-management strategies and only proposed potential strategies. Therefore, outcomes of these included articles could not be provided. Level of evidence according to Sackett criteria proposed by Teasell et al. [36] .

Included peer-reviewed literature came from 20 countries, with over half of the studies being conducted in the USA (58%, 47/118) and the UK (16%, 19/118). Similarly, for the gray literature, strategies were found to originate from 7 countries, with almost 80% of the technologies being from the USA and UK (75% USA, 12% Canada, and 7% UK). Publication year of the included peer-reviewed literature varied, with wander-management strategy publications appearing in the early 1990s, and the total number of publications increasing over the last 27 years. A trend was evident pertaining to the type of strategy being published, where there has been a predominant focus on high- versus low-tech strategies over the last decade.

3.1. Features of wander-management technologies

3.1.1. wander-management strategy—type used and strategy specifications.

A total of 183 high-tech strategies (109 from peer-reviewed and 74 from gray literature) and 143 low-tech strategies (85 from peer-reviewed and 58 from gray literature) were included in this scoping review and included 6 subcategories of high-tech strategies and 14 subcategories of low-tech strategies. The most commonly used high-tech subcategories from the scholarly literature were locating strategies (i.e., GPS, radio frequency, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi; 71.6%, 78/109) and alarm and sensors (i.e., motion and occupancy sensors, monitors, and optical systems; 19.3%, 21/109). The most commonly used high-tech subcategories from the gray literature were also locating technologies (i.e., GPS and radio frequency; 63.5%, 47/74) and alarm and sensors (i.e., motion sensors; 35.1%, 26/74) ( Fig. 2 ). The most commonly used low-tech subcategories from the scholarly literature were distraction/redirection strategies (i.e., doll therapy, music therapy, mirrors in front of exit doors, visual barriers such as cloth on exit doors or door murals, and the integration of purposeful activities such as chores and crafts; 35.3%, 30/85), exercise groups (i.e., walking; 12.9%, 11/85), and identification strategies (i.e., ID cards, labels, and the Safe Return Program; 8.2%, 7/85) ( Fig. 2 ). The most commonly used low-tech subcategories from the gray literature were distraction/redirection strategies (i.e., visual barriers, planning meaningful activities, animal therapy; 25.9%, 15/58), locks/barriers (i.e., door locks; 15.5%, 9/58), and identification strategies (i.e., Safe Return and Medic Alert; 12.1%, 7/58) ( Fig. 2 ).

Number of strategies that were high (n = 183) and low (n = 142) tech.

3.1.2. Product readiness level

For the peer-reviewed articles, two were in the analytical and experimental critical functions phase (PRL3), and 21 were either in development and testing phases in laboratory, or validated in relevant environments (PRL 4 and 5), or the technologies were in demonstration or pilot phase (PRL6). The remaining 31 articles contained strategies either prototypes near or planned in an operational system or were mature strategies in which actual systems operated over the full range of expected conditions (PRL9) ( Table 1 ). A total of 19 high-tech articles, 34 low-tech articles, and 11 articles containing both high- and low-tech strategies could not be classified using the PRL scale. Primary reasons were due to the high number of review articles included in this study, in addition to many strategies that were proposed but not evaluated. Articles containing both high- and low-tech solutions were found to have the highest technology readiness level (PRL9), in comparison with high-tech–only articles with an average PRL7 and low-tech–only strategies with an average PRL7.

3.2. Descriptive analysis of studies

3.2.1. characteristics of the research conducted in wander-management technologies.

- (a) Participant characteristics, sample size, length, and location of included studies. Participants of the included studies had a mean age of 75 years (SD 9.7). The age ranged from 23 to 90 years for caregivers and 60 to 103 years for persons with dementia, with a high dispersion in the number of participants (i.e., mean of n = 217 and SD = 77.2). Although all peer-reviewed articles included persons with dementia, only 19 articles (16%, 19/118) specified their underlying degree of dementia and level of cognitive decline. Almost 43% (38/88) of the included clinically oriented studies were small trials with a total number of participants less than 50 (i.e., mean of n = 10.8; SD 10.0), whereas the remaining trials can be described as medium-large (i.e., >50) with a mean of n = 200.5 (SD 338.0). No mean differences were found across low- and high-tech strategy studies for small and medium-large trials ( P > .05). Of the 88 included clinical studies, 29 did not report sample size and therefore were not included in the aforementioned calculations. Fourteen studies involved caregivers; however, only seven reported the relationship between the individual with dementia and caregiver. The most common type of family caregiver was a combination of children and spouse (18.6%), followed by spouse only (17.7%), and children (16.7%). Professional caregivers, search and rescue workers, and nurses were also included, making up nearly half of the reported involved stakeholders (40.3%). Forty-three of the studies reported the ratio of male-to-female dementia clients and caregivers. The average total number of females included in this review was 60 (SD 27), whereas the average total number of males included in this review was 39 (SD 36). Only 11 of the 118 studies reported ethnicity of participants. Of these, two were 100% Caucasian, five were more than 70% Caucasian, four were 100% Asian, and five contained <25% for Latino, African American, and African Caribbean decent. The lengths of the included studies varied (mean 4.8 months; SD 11.5). Only 57 of the 118 studies (48%) reported the location of the study. The setting of tests for the included studies ranged from long-term care (43.9%), community (26.3%), laboratory (10.5%), home (7.0%), hospital (5.3%), assisted living (3.5%), and outdoor environments (3.5%).

Table 2

High-tech main outcomes of scholarly literature

Abbreviations: RFID, radio-frequency identification; GPS, global positioning system; RF, radio frequency.

The outcome variables for low-tech strategies included wandering prevalence/frequency, attempted door testing/exiting/entries, total time seated, number of aggressive events, restlessness, and success facilitating return of the missing person ( Table 3 ). For the measures used to assess the proposed outcome variables, 17 measures were reported, and of these, 76% (13/17) were different. The most commonly used approaches were time between door testing/exiting (4/17) and observations (3/17). Finally, the outcome variables for studies that included low- and high-tech strategies included effectiveness of the intervention, experience and advise using the different strategies, acceptability related to the intervention, distance of wandering, and agitation and irritability ( Tables 2 and and3). 3 ). For the measures used to assess the proposed outcome variables, 16 measures were reported, and of these, 88% (14/16) were different. The most commonly used approaches were interviews (2/16) and observations (2/16).

Table 3

Low-tech main outcomes of scholarly literature

For the overall outcomes, 48.3% (57/118) of the included peer-reviewed literature showed advantages of wander-management strategies in terms of managing wandering in persons with dementia. Forty-eight of the 118 studies reported negative or nonsignificant differences, but positive versus negative outcomes were not significantly different ( P > .05). When separating the number of positive and negative or mixed outcomes by technology complexity, 52% (32/61) of the high-tech strategies, 50% (21/42) of the low-tech strategies, and 27% (4/15) of the studies that included both low- and high-tech strategies demonstrated positive results. Thirteen studies did not include results that evaluated wander-management strategies; therefore, they were not included in calculations. The above indicates that although the implementation of strategies to manage the adverse outcomes associated with wandering is promising, there is significant room for improvement and requires further investigation. Table 1 shows the number of studies classifying the positive and negative outcomes per device type, in addition to details on the total number of participants and study design types.

- (c) Evidence of the clinical outcomes. The level of scientific evidence of the clinical-oriented studies that evaluated wander-management strategies using quantitative methods was low. Regarding the level of scientific evidence for the studies that evaluated high-tech strategies, only one article incorporated an RCT design [13] ; however, details were not explained. Ten papers used a cross-sectional design. All studies were at a level of evidence 5, and results indicated that high-tech strategies have great potential for locating the wanderer quickly; however, many devices do not follow to their claims, which could in part be due to the low quality of effectiveness testing. GPS locating devices consistently demonstrated superior accuracy to radio frequency devices. Family caregivers were perceived significantly more important in the decision-making process than figures outside of the family. Four studies used a single-case study design without a baseline phase, also at a level of evidence 5, indicating that individuals with mild dementia are capable of following vibrotactile signals, that wandering detection devices can contribute toward improved safety by identifying attempts to elope by setting up alarms and sensors, and that locating devices demonstrate promise as a novel and competent healthcare approach in the case of dementia scenarios. Seven studies used qualitative approaches, which cannot be assessed using Sackett's criteria [36] .

Regarding low-tech strategies, only one study incorporated an RCT design. This RCT [40] achieved a PEDro score of 5, with a level of evidence 2, where adapted exercise games (i.e., active activities with a softball) significantly decreased agitated behaviors, such as searching or wandering behaviors (54%, P < .05), whereas escaping restraints had no significant change (40%, P = .07). Four articles used a cross-sectional design with a level of evidence 5, and results indicated that lighting conditions had no effect on disruptive behaviors such as door testing/exiting, and few persons with dementia who exercises in ways other than walking may influence sundown syndrome and sleep quality. Four studies used a single-case study design with a baseline phase and had a level of evidence 4, indicating that cloth barriers reduced entry into restricted areas with a high treatment acceptability, music therapy can increase the amount of time seated by the persons with dementia, and highlighted the need to educate caregivers that all persons with dementia are at risk of getting lost, regardless of whether they have exhibited the risky behavior in the past. Early education would allow caregivers to adopt preventative measures to reduce these impending risks. One study used a pretest-posttest design, with a level of evidence of 4. Results demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating a wall mural painted on the entrance of doorways, through the reduction of door testing behaviors exhibited by the participants. Two articles used qualitative methods, which cannot be assessed using Sackett's criteria [36] .

Regarding studies that included high- and low-tech solutions, one study included an RCT design [41] ; however, the details were not explained. Results from this study highlighted that most devices presently used by family caregivers do not comprise new technology but rather use established items, such as baby monitors, and home modifications that are recommended by an occupational or physical therapist. There was level 5 evidence from two case study [42] , [43] designs indicating that no evidence of benefit from exercise or walking therapies were found, that tracking devices and home alarms and sensors both effectively detected wandering and locating lost patients in uncontrolled, nonrandomized studies, and that IC tag monitoring system needed further improvement for clinical use.

- (d) Usability and strategy acceptance. Of the peer-reviewed studies, 12% (13 studies) aimed to study the usability and acceptance of wander-management strategies. Of these, nine (69%, 9/13) examined acceptance of high-tech solutions and 4 (31%, 4/13) examined acceptance of low-tech solutions. Overall acceptability and usability of these strategies were high among participants. For example, one study found that most respondents agreed that the use of locator devices was superior to existing search methods and would improve quality of life of caregivers and persons with dementia, that they were appropriate devices, and that they could operate the device successfully [24] . Those who were more inclined to use wander-management technologies were older adults who had been lost once or more (89%) or who had been diagnosed with mild dementia and had a history of being lost (73%) [44] . For low-tech solutions, cloth barriers, for example, were found to have high treatment acceptability [22] . Low-tech solutions were also seen as strategies that have already been implemented within a person's home, in part due to their affordable nature, and as established strategies that result from professional recommendations from occupational and physical therapists [41] .

- (e) Although the acceptability of certain strategies was high, others did not have the same result. Locator devices used by Yung-Ching & Leung (2012) [44] , for example, were met with resistance. Barriers toward the implementation of wander-management strategies are suggested to be partly related to caregivers' acceptance of the suggestions, which they often perceive as not necessary or that they would not work in their situation. In addition to acceptance of wander-management strategies, barriers on the use of high-tech strategies include concerns about damaging the device, cost of equipment, difficulties in using the strategy, false alarms caused by the device, uncomfortable wear of the device, inaccuracy of the coordinates for locator devices, forgetting to wear the device, and concerns about privacy and stigmatization. Device esthetics was also considered important in purchase consideration [44] . Barriers on the use of low-tech strategies include participants not being aware of the strategy (e.g., mirrors and grids on doors), not enough staff to implement the strategy (e.g., exercise programs), poor product design, unavailability or lack of cooperation, issues with building codes (i.e., locked door strategies), and the implementation of the strategy being challenging due to raised ethical concerns (i.e., doll therapy being seen as demeaning and patronizing).

Table 4

Ethical concerns associated with wander-management strategies

4. Discussion

This review examined the range and extent of all possible strategies used to manage wandering behavior in persons with dementia. We included 118 studies (of 4096) and 130 strategies from the gray literature. Overall, 183 high- and 143 low-tech strategies were included, with the majority (59.5%) of the strategies being derived from the scholarly literature. The percentage of strategies derived from scholarly and gray literature differs from that of Neubauer et al. [25] where most strategies were from the gray literature. This is in part due to the addition of low-tech solutions and studies that do not evaluate the usability or effectiveness of the wander-management strategies to the current review. Of the 296 strategies, there were 183 high- and 143 low-tech solutions. Of these, there were six different subcategories of high- and 14 different subcategories of low-tech strategies, with locating strategies, alarms and sensors, and distraction/redirection strategies were the most common. Of the 118 included studies, less than half (48.3%) evaluated the usability or effectiveness of the strategies.

Only 16% were clinically tested in home or community settings, and 25% were tested in formal care settings. In addition, all testing locations took place in urban settings. The lack of real-world evaluation raises question about the degree of effectiveness of the proposed wander-management strategies, and whether users are able and willing to adopt these solutions. In addition, rural regions were significantly underrepresented, leaving out a significant cohort, which may have presented different and necessary views by caregivers on the use and integration of these interventions in their communities [46] . An increased focus on usability testing in home-based rural and urban settings and the use of user-centered and participatory design approaches would enable real users to identify problems with existing strategy designs, which could enhance adoption and acceptance of wander-management strategies [47] .

Aside from a lack of usability testing and user-centered approaches of wander-management strategies, available solutions were difficult to find and were vastly scattered across the gray literature. Most high-tech solutions were available through an array of commercial websites selling the technology. Two websites, tech.findingyourwayontario.ca and alzstore.com , were the only websites containing strategies from multiple companies. Low-tech solutions were primarily suggested in Alzheimer's-specific websites such as through the Alzheimer Association; however, little information was provided on where or how to access these strategies. In addition, no website provided an in-depth description of all available low- and high-tech wander-management strategies. These findings help to support difficulties caregivers and persons with dementia may face when trying to choose a strategy that works best for their individual needs. A guideline available through different mediums and locations is therefore necessary to simplify this information for a population that is often time constrained due to their caregiving responsibilities [48] .

Although the mass diversity of wander-management strategies may be promising in terms of having multiple options to help serve the unique needs of persons with dementia and their caregivers, only 13% of studies (15/118) in this review included high- and low-tech strategies together. Even fewer (2%; 2/118) compared their effectiveness. This raises the question whether certain high- and low-tech strategies are more effective than others, and if various combinations of wander-management strategies are necessary to meet the unique needs of persons with dementia and their family caregivers. Some persons with dementia, for example, wander inside and outside of their homes [49] , whereas some may only wander in one of these settings. In terms of living arrangements, there are a growing number of persons with dementia who are living at home alone in the community, changing the scope of how one might care for these individuals [50] . When looking at the diverse context of those affected by dementia, income levels, perceptions of risk associated with wandering behavior, culture, and beliefs may all play key roles in the successful adoption of wander-management strategies [46] . These factors, however, have yet to be evaluated within the present literature.

In addition to examining the range and scope of high- and low-tech wander-management strategies in this review, we wanted to identify their level of product readiness, and to characterize the present evidence on the implementation of such interventions. Overall, most peer-reviewed articles described strategies in which they were prototypes that were planned in an operational setting. This signifies the positive state of wander-management strategies in that most have been tested in a relevant environment and are in the process of being deployed in operational environments. Despite the potential advantages of using high- and low-tech strategies to manage wandering, only 52% (61/118) of the studies could be evaluated using the PRL scale because many studies were only proposing the strategy. With 194 different high- and low-tech strategies being included in the scholarly literature alone, this highlights the sheer infancy of present strategies that are being used to manage wandering. Further research in this area is therefore required because of the low percentage of strategies that could be evaluated using the PRL scale.

Mixed outcomes were found for both high- and low-tech strategies, where positive outcomes were found for 52% of the included high-tech strategies and 50% for the low-tech strategies. Overall, the use of nonconstraining strategies provided promise to facilitate persons with dementia to support independence and enable them to engage in meaningful activities, such as walking and remaining engaged within their community [51] . For high-tech strategies, locating technologies, such as GPS and RFID devices, were suggested to have great potential for locating wandering persons with dementia quickly, provides increased confidence and peace of mind of caregivers, and was found to be a preferred option by users. The implementation of alarms and surveillance strategies were also promising. Issues, however, such as cost, over sensitivity, appearance, privacy, stigma, and the need to combine multiple products to meet the variable needs of users, are to be considered. For low-tech interventions, strategies such as door murals, methods of distraction, visual barriers, exercise programs, and therapies (i.e., doll and music therapy) all demonstrated reductions in wandering and exit seeking behaviors. Conflicting evidence, however, was found across all strategies, and scientific rigor was repeatedly mentioned as being poor quality [52] . This raises questions on the feasibility and effectiveness of the adoption of these strategies in formal and community-based settings. Aside from the outcomes that measured caregivers' perceptions on strategies to manage wandering, like the findings of Neubauer et al. [25] , none of the included studies addressed the needs and opinions of persons with dementia, more specifically those with mild dementia. Although addressing the concerns of family caregivers is important, the end outcome of these strategies is to ensure the safety of persons with dementia at risk of getting lost. The involvement of both caregivers and persons with dementia in the design and implementation of wander-management strategies is therefore critical to enable enhanced user satisfaction, adherence, and inevitably improved safety and quality of life of persons with dementia.

The significant variation of included outcomes, participant type, assessment tools, study duration, testing settings, and study design may have influenced the mixed outcomes of the high- and low-tech wander-management strategies. Intervention implementation, for example, ranged from 25 minutes to 1 year, with most (78%) being only applied for 3 months or less. The high variation and short study length indicates a need to determine a duration that is best suited for strategy development and evaluation. Longitudinal field studies are also required to identify the long-term impact of each wander-management strategy, and there remains a critical need for standardized outcomes to compare the effectiveness of strategies to manage wandering. Other measures based on models such as the Technology Acceptance Model [53] and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology [54] are necessary to ensure strategies are designed in a way that take into consideration factors that are essential to user adoption. The level of scientific evidence provided by clinical-oriented studies that used quantitative methods is low as the highest level per Sackett criteria [36] was 2, with most studies containing at level of evidence of 4 or less for both high and low tech included studies. Thus, there is a need for more RCT studies to increase the level of evidence of wander-management strategies for persons with dementia.

Finally, there is a gap in the literature with respect to privacy and ethics of persons affected using wander-management strategies. There has been no approach or recommendations published to address ethical issues. Future studies on privacy versus safety, the influence of stigma, and conflicts of interest between caregivers and persons with dementia need to be further explored.

4.1. Limitations of this review

We could only quantitatively assess the strength of studies that used RCTs (using PEDro scale); as far as we know there is no standardized scale that determines the quality of either quantitative or qualitative non-RCT studies. Although there are tools and guidelines available for performing a critical appraisal of research literature, the result was a proxy measure of quality. Without a scale, comparison of the relative quality of the included studies was not possible.

5. Future research and conclusions

From this review, we can conclude that many high- and low-tech strategies exist to manage the negative outcomes associated with wandering in persons with dementia. There is a general agreement that wander-management strategies can reduce risks associated with wandering, while enabling persons with dementia with a sense of freedom and independence. Further research could determine the factors that may influence intervention adoption and demonstrate the efficacy of high- and low-tech wander-management strategies.

Research in Context

- 1. Systematic review: We conducted an extensive search on gray and scholarly literature databases. Three levels of screening were employed, that is, title screening, abstract screening, and full-text screening.

- 2. Interpretation: We identified six categories of high-tech and 14 subcategories of low-tech strategies that can be used by caregivers and persons with dementia. Although wander-management strategies were believed to mitigate the risks associated with wandering, few addressed ethical issues, few were evaluated in community settings, and the overall scientific evidence from these outcomes was low. Available solutions were scattered across the gray literature and difficult to find.

- 3. Future directions: Rigorous research is required to demonstrate the efficacy of high- and low-tech wander-management strategies and their feasibility in urban and rural community-dwelling environments. A guideline is also necessary to simplify all possible strategy types and to allow stakeholders to choose wander-management strategies based on their individual needs.

Acknowledgments

The first author received support from the Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital through the Dr. Peter N. McCracken Legacy Scholarship, Thelma R. Scambler Scholarship, Gyro Club of Edmonton Graduate Scholarship, and the Alberta Association on Gerontology Edmonton Chapter Student Award.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2018.08.001 .

Supplementary data

Jump to navigation

- Bahasa Malaysia

Medicines for sleep problems in dementia

People with dementia frequently experience sleep disturbances. These can include reduced sleep at night, frequent wakening, wandering at night, and sleeping excessively during the day.

These behaviours cause a lot of stress to carers, and may be associated with earlier admission to institutional care for people with dementia. They can also be difficult for care-home staff to manage.

Non-drug approaches to treatment should be tried first, However, these may not help and medicines are often used. Since the source of the sleep problems may be changes in the brain caused by dementia, it is not clear whether normal sleeping tablets are effective for people with dementia, and there are worries that the medicines could cause significant side effects (harms).

The purpose of this review

In this updated Cochrane review, we tried to identify the benefits and common harms of any medicine used to treat sleep problems in people with dementia.

Findings of this review

We searched up to February 2020 for well-designed trials that compared any medicine used for treating sleep problems in people with dementia with a fake medicine (placebo). We consulted a panel of carers to help us identify the most important outcomes to look for in the trials.

We found nine trials (649 participants) investigating four types of medicine: melatonin (five trials), trazodone (one trial), ramelteon (one trial), and orexin antagonists (two trials). Participants in all the trials had dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. The ramelteon trial, one melatonin trial, and both orexin antagonist trials were commercially funded. Overall, the evidence was moderate or low quality, meaning that further research is likely to affect the results.

Participants in the trazodone trial and most of those in the melatonin trials had moderate-to-severe dementia, while those in the ramelteon and orexin antagonist trials had mild-to-moderate dementia.

The five melatonin trials included 253 participants. We found no evidence that melatonin improved sleep in people with dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. The ramelteon trial had 74 participants. The limited information available did not provide any evidence that ramelteon was better than placebo. There were no serious harms for either medicine.

The trazodone trial had only 30 participants. It showed that a low dose of the sedative antidepressant trazodone, 50 mg, given at night for two weeks, may increase the total time spent asleep each night (an average of 43 minutes more in the trial) and may improve sleep efficiency (the percentage of time in bed spent sleeping). It may have slightly reduced the time spent awake at night after first falling asleep, but we could not be sure of this effect. It did not reduce the number of times the participants woke up at night. There were no serious harms reported.

The two orexin antagonist trials had 323 participants. We found evidence that an orexin antagonist probably has some beneficial effects on sleep. On average, participants in the trials slept 28 minutes longer at night and spent 15 minutes less time awake after first falling asleep. There was also a small increase in sleep efficiency, but no evidence of an effect on the number of times participants woke up. Side effects were no more common in participants taking the drugs than in those taking placebo.

The drugs that appeared to have beneficial effects on sleep did not seem to worsen participants' thinking skills, but these trials did not assess participants' quality of life, or look in any detail at outcomes for carers.

Shortcomings of this review

Although we searched for them, we were unable to find any trials of other sleeping medications that are commonly prescribed to people with dementia. All participants had dementia due to Alzheimer's disease, although sleep problems are also common in other forms of dementia. No trials assessed how long participants spent asleep without interruption, a high priority outcome to our panel of carers. Only four trials measured side effects systematically.

We concluded that there are significant gaps in the evidence needed to guide decisions about medicines for sleeping problems in dementia. More trials are required to inform medical practice. It is essential that trials include careful assessment of side effects.

We discovered a distinct lack of evidence to guide decisions about drug treatment of sleep problems in dementia. In particular, we found no RCTs of many widely prescribed drugs, including the benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, although there is considerable uncertainty about the balance of benefits and risks for these common treatments. We found no evidence for beneficial effects of melatonin (up to 10 mg) or a melatonin receptor agonist. There was evidence of some beneficial effects on sleep outcomes from trazodone and orexin antagonists and no evidence of harmful effects in these small trials, although larger trials in a broader range of participants are needed to allow more definitive conclusions to be reached. Systematic assessment of adverse effects in future trials is essential.

Sleep disturbances, including reduced nocturnal sleep time, sleep fragmentation, nocturnal wandering, and daytime sleepiness are common clinical problems in dementia, and are associated with significant carer distress, increased healthcare costs, and institutionalisation. Although non-drug interventions are recommended as the first-line approach to managing these problems, drug treatment is often sought and used. However, there is significant uncertainty about the efficacy and adverse effects of the various hypnotic drugs in this clinically vulnerable population.

To assess the effects, including common adverse effects, of any drug treatment versus placebo for sleep disorders in people with dementia.

We searched ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois), the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group's Specialized Register, on 19 February 2020, using the terms: sleep, insomnia, circadian, hypersomnia, parasomnia, somnolence, rest-activity, and sundowning.

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared a drug with placebo, and that had the primary aim of improving sleep in people with dementia who had an identified sleep disturbance at baseline.

Two review authors independently extracted data on study design, risk of bias, and results. We used the mean difference (MD) or risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) as the measures of treatment effect, and where possible, synthesised results using a fixed-effect model. Key outcomes to be included in our summary tables were chosen with the help of a panel of carers. We used GRADE methods to rate the certainty of the evidence.

We found nine eligible RCTs investigating: melatonin (5 studies, n = 222, five studies, but only two yielded data on our primary sleep outcomes suitable for meta-analysis), the sedative antidepressant trazodone (1 study, n = 30), the melatonin-receptor agonist ramelteon (1 study, n = 74, no peer-reviewed publication), and the orexin antagonists suvorexant and lemborexant (2 studies, n = 323).

Participants in the trazodone study and most participants in the melatonin studies had moderate-to-severe dementia due to Alzheimer's disease (AD); those in the ramelteon study and the orexin antagonist studies had mild-to-moderate AD. Participants had a variety of common sleep problems at baseline. Primary sleep outcomes were measured using actigraphy or polysomnography. In one study, melatonin treatment was combined with light therapy. Only four studies systematically assessed adverse effects. Overall, we considered the studies to be at low or unclear risk of bias.

We found low-certainty evidence that melatonin doses up to 10 mg may have little or no effect on any major sleep outcome over eight to 10 weeks in people with AD and sleep disturbances. We could synthesise data for two of our primary sleep outcomes: total nocturnal sleep time (TNST) (MD 10.68 minutes, 95% CI –16.22 to 37.59; 2 studies, n = 184), and the ratio of day-time to night-time sleep (MD –0.13, 95% CI –0.29 to 0.03; 2 studies; n = 184). From single studies, we found no evidence of an effect of melatonin on sleep efficiency, time awake after sleep onset, number of night-time awakenings, or mean duration of sleep bouts. There were no serious adverse effects of melatonin reported.

We found low-certainty evidence that trazodone 50 mg for two weeks may improve TNST (MD 42.46 minutes, 95% CI 0.9 to 84.0; 1 study, n = 30), and sleep efficiency (MD 8.53%, 95% CI 1.9 to 15.1; 1 study, n = 30) in people with moderate-to-severe AD. The effect on time awake after sleep onset was uncertain due to very serious imprecision (MD –20.41 minutes, 95% CI –60.4 to 19.6; 1 study, n = 30). There may be little or no effect on number of night-time awakenings (MD –3.71, 95% CI –8.2 to 0.8; 1 study, n = 30) or time asleep in the day (MD 5.12 minutes, 95% CI –28.2 to 38.4). There were no serious adverse effects of trazodone reported.

The small (n = 74), phase 2 trial investigating ramelteon 8 mg was reported only in summary form on the sponsor's website. We considered the certainty of the evidence to be low. There was no evidence of any important effect of ramelteon on any nocturnal sleep outcomes. There were no serious adverse effects.

We found moderate-certainty evidence that an orexin antagonist taken for four weeks by people with mild-to-moderate AD probably increases TNST (MD 28.2 minutes, 95% CI 11.1 to 45.3; 1 study, n = 274) and decreases time awake after sleep onset (MD –15.7 minutes, 95% CI –28.1 to –3.3: 1 study, n = 274) but has little or no effect on number of awakenings (MD 0.0, 95% CI –0.5 to 0.5; 1 study, n = 274). It may be associated with a small increase in sleep efficiency (MD 4.26%, 95% CI 1.26 to 7.26; 2 studies, n = 312), has no clear effect on sleep latency (MD –12.1 minutes, 95% CI –25.9 to 1.7; 1 study, n = 274), and may have little or no effect on the mean duration of sleep bouts (MD –2.42 minutes, 95% CI –5.53 to 0.7; 1 study, n = 38). Adverse events were probably no more common among participants taking orexin antagonists than those taking placebo (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.99; 2 studies, n = 323).

Call our 24 hours, seven days a week helpline at 800.272.3900

- Professionals

- Younger/Early-Onset Alzheimer's

- Is Alzheimer's Genetic?

- Women and Alzheimer's

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies

- Down Syndrome & Alzheimer's

- Frontotemporal Dementia

- Huntington's Disease

- Mixed Dementia

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Parkinson's Disease Dementia

- Vascular Dementia

- Korsakoff Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Know the 10 Signs

- Difference Between Alzheimer's & Dementia

- 10 Steps to Approach Memory Concerns in Others

- Medical Tests for Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Why Get Checked?

- Visiting Your Doctor

- Life After Diagnosis

- Stages of Alzheimer's

- Earlier Diagnosis

- Part the Cloud

- Research Momentum

- Our Commitment to Research

- TrialMatch: Find a Clinical Trial

- What Are Clinical Trials?

- How Clinical Trials Work

- When Clinical Trials End

- Why Participate?

- Talk to Your Doctor

- Clinical Trials: Myths vs. Facts

- Can Alzheimer's Disease Be Prevented?

- Brain Donation

- Navigating Treatment Options

- Lecanemab Approved for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease

- Aducanumab Discontinued as Alzheimer's Treatment

- Medicare Treatment Coverage

- Donanemab for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease — News Pending FDA Review

- Questions for Your Doctor

- Medications for Memory, Cognition and Dementia-Related Behaviors

- Treatments for Behavior

- Treatments for Sleep Changes

- Alternative Treatments

- Facts and Figures

- Assessing Symptoms and Seeking Help

- Now is the Best Time to Talk about Alzheimer's Together

- Daily Care Plan

- Communication and Alzheimer's

- Food and Eating

- Art and Music

- Incontinence

- Dressing and Grooming

- Dental Care

- Working With the Doctor

- Medication Safety

- Accepting the Diagnosis

- Early-Stage Caregiving

- Middle-Stage Caregiving

- Late-Stage Caregiving

- Aggression and Anger

- Anxiety and Agitation

- Hallucinations

- Memory Loss and Confusion

- Sleep Issues and Sundowning

- Suspicions and Delusions

- In-Home Care

- Adult Day Centers

- Long-Term Care

- Respite Care

- Hospice Care

- Choosing Care Providers

- Finding a Memory Care-Certified Nursing Home or Assisted Living Community

- Changing Care Providers

- Working with Care Providers

- Creating Your Care Team

- Long-Distance Caregiving

- Community Resource Finder

- Be a Healthy Caregiver

- Caregiver Stress

- Caregiver Stress Check

- Caregiver Depression

- Changes to Your Relationship

- Grief and Loss as Alzheimer's Progresses

- Home Safety

- Dementia and Driving

- Technology 101

- Preparing for Emergencies

- Managing Money Online Program

- Planning for Care Costs

- Paying for Care

- Health Care Appeals for People with Alzheimer's and Other Dementias

- Social Security Disability

- Medicare Part D Benefits

- Tax Deductions and Credits

- Planning Ahead for Legal Matters

- Legal Documents

- Get Educated

- Just Diagnosed

- Sharing Your Diagnosis

- Changes in Relationships

- If You Live Alone

- Treatments and Research

- Legal Planning

- Financial Planning

- Building a Care Team

- End-of-Life Planning

- Programs and Support

- Overcoming Stigma

- Younger-Onset Alzheimer's

- Taking Care of Yourself

- Reducing Stress

- Tips for Daily Life

- Helping Family and Friends

- Leaving Your Legacy

- Live Well Online Resources

- Make a Difference

- ALZ Talks Virtual Events

- ALZNavigator™

- Veterans and Dementia

- The Knight Family Dementia Care Coordination Initiative

- Online Tools

- Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Alzheimer's

- Native Americans and Alzheimer's

- Black Americans and Alzheimer's

- Hispanic Americans and Alzheimer's

- LGBTQ+ Community Resources for Dementia

- Educational Programs and Dementia Care Resources

- Brain Facts

- 50 Activities

- For Parents and Teachers

- Resolving Family Conflicts

- Holiday Gift Guide for Caregivers and People Living with Dementia

- Trajectory Report

- Resource Lists

- Search Databases

- Publications

- Favorite Links

- 10 Healthy Habits for Your Brain

- Stay Physically Active

- Adopt a Healthy Diet

- Stay Mentally and Socially Active

- Online Community

- Support Groups

Find Your Local Chapter

- Any Given Moment

- New IDEAS Study

- RFI Amyloid PET Depletion Following Treatment

- Bruce T. Lamb, Ph.D., Chair

- Christopher van Dyck, M.D.

- Cynthia Lemere, Ph.D.

- David Knopman, M.D.

- Lee A. Jennings, M.D. MSHS

- Karen Bell, M.D.

- Lea Grinberg, M.D., Ph.D.

- Malú Tansey, Ph.D.

- Mary Sano, Ph.D.

- Oscar Lopez, M.D.

- Suzanne Craft, Ph.D.

- About Our Grants

- Andrew Kiselica, Ph.D., ABPP-CN

- Arjun Masurkar, M.D., Ph.D.

- Benjamin Combs, Ph.D.

- Charles DeCarli, M.D.

- Damian Holsinger, Ph.D.

- David Soleimani-Meigooni, Ph.D.

- Donna M. Wilcock, Ph.D.

- Elizabeth Head, M.A, Ph.D.

- Fan Fan, M.D.

- Fayron Epps, Ph.D., R.N.

- Ganesh Babulal, Ph.D., OTD

- Hui Zheng, Ph.D.

- Jason D. Flatt, Ph.D., MPH

- Jennifer Manly, Ph.D.

- Joanna Jankowsky, Ph.D.

- Luis Medina, Ph.D.

- Marcello D’Amelio, Ph.D.

- Marcia N. Gordon, Ph.D.

- Margaret Pericak-Vance, Ph.D.

- María Llorens-Martín, Ph.D.

- Nancy Hodgson, Ph.D.

- Shana D. Stites, Psy.D., M.A., M.S.

- Walter Swardfager, Ph.D.

- ALZ WW-FNFP Grant

- Capacity Building in International Dementia Research Program

- ISTAART IGPCC

- Alzheimer’s Disease Strategic Fund: Endolysosomal Activity in Alzheimer’s (E2A) Grant Program

- Imaging Research in Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Zenith Fellow Awards

- National Academy of Neuropsychology & Alzheimer’s Association Funding Opportunity

- Part the Cloud-Gates Partnership Grant Program: Bioenergetics and Inflammation

- Pilot Awards for Global Brain Health Leaders (Invitation Only)

- Robert W. Katzman, M.D., Clinical Research Training Scholarship

- Funded Studies

- How to Apply

- Portfolio Summaries

- Supporting Research in Health Disparities, Policy and Ethics in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Research (HPE-ADRD)

- Diagnostic Criteria & Guidelines

- Annual Conference: AAIC

- Professional Society: ISTAART

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: DADM

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: TRCI

- International Network to Study SARS-CoV-2 Impact on Behavior and Cognition

- Alzheimer’s Association Business Consortium (AABC)

- Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium (GBSC)

- Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network

- International Alzheimer's Disease Research Portfolio

- Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Private Partner Scientific Board (ADNI-PPSB)

- Research Roundtable

- About WW-ADNI

- North American ADNI

- European ADNI

- Australia ADNI

- Taiwan ADNI

- Argentina ADNI

- WW-ADNI Meetings

- Submit Study

- RFI Inclusive Language Guide

- Scientific Conferences

- AUC for Amyloid and Tau PET Imaging

- Make a Donation

- Walk to End Alzheimer's

- The Longest Day

- RivALZ to End ALZ

- Ride to End ALZ

- Tribute Pages

- Gift Options to Meet Your Goals

- Founders Society

- Fred Bernhardt

- Anjanette Kichline

- Lori A. Jacobson

- Pam and Bill Russell

- Gina Adelman

- Franz and Christa Boetsch

- Adrienne Edelstein

- For Professional Advisors

- Free Planning Guides

- Contact the Planned Giving Staff

- Workplace Giving

- Do Good to End ALZ

- Donate a Vehicle

- Donate Stock

- Donate Cryptocurrency

- Donate Gold & Sterling Silver

- Donor-Advised Funds

- Use of Funds

- Giving Societies

- Why We Advocate

- Ambassador Program

- About the Alzheimer’s Impact Movement

- Research Funding

- Improving Care

- Support for People Living With Dementia

- Public Policy Victories

- Planned Giving

- Community Educator

- Community Representative

- Support Group Facilitator or Mentor

- Faith Outreach Representative

- Early Stage Social Engagement Leaders

- Data Entry Volunteer

- Tech Support Volunteer

- Other Local Opportunities

- Visit the Program Volunteer Community to Learn More

- Become a Corporate Partner

- A Family Affair

- A Message from Elizabeth

- The Belin Family

- The Eliashar Family

- The Fremont Family

- The Freund Family

- Jeff and Randi Gillman

- Harold Matzner

- The Mendelson Family

- Patty and Arthur Newman

- The Ozer Family

- Salon Series

- No Shave November

- Other Philanthropic Activities

- Still Alice

- The Judy Fund E-blast Archive

- The Judy Fund in the News

- The Judy Fund Newsletter Archives

- Sigma Kappa Foundation

- Alpha Delta Kappa

- Parrot Heads in Paradise

- Tau Kappa Epsilon (TKE)

- Sigma Alpha Mu

- Alois Society Member Levels and Benefits

- Alois Society Member Resources

- Zenith Society

- Founder's Society

- Joel Berman

- JR and Emily Paterakis

- Legal Industry Leadership Council

- Accounting Industry Leadership Council

Find Local Resources

Let us connect you to professionals and support options near you. Please select an option below:

Use Current Location Use Map Selector

Search Alzheimer’s Association

Sundowning is increased confusion that people living with Alzheimer's and dementia may experience from dusk through night. Also called "sundowner's syndrome," it is not a disease but a set of symptoms or dementia-related behaviors that may include difficulty sleeping, anxiety, agitation, hallucinations, pacing and disorientation. Although the exact cause is unknown, sundowning may occur due to disease progression and changes in the brain.

Factors that may contribute to trouble sleeping and sundowning

Tips that may help manage sleep issues and sundowning, if the person is awake and upset.

- Mental and physical exhaustion from a full day of activities.

- Navigating a new or confusing environment.

- A mixed-up "internal body clock." The person living with Alzheimer's may feel tired during the day and awake at night.

- Low lighting can increase shadows, which may cause the person to become confused by what they see. They may experience hallucinations and become more agitated.

- Noticing stress or frustration in those around them may cause the person living with dementia to become stressed as well.

- Dreaming while sleeping can cause disorientation, including confusion about what's a dream and what's real.

- Less need for sleep, which is common among older adults.

Share your experiences and find support

Join ALZConnected®, a free online community designed for people living with dementia and those who care for them. Post questions about dementia-related issues, offer support, and create public and private groups around specific topics.

- Encourage the person living with dementia to get plenty of rest.

- Schedule activities such as doctor appointments, trips and bathing in the morning or early afternoon hours when the person living with dementia is more alert.

- Encourage a regular routine of waking up, eating meals and going to bed.

- When possible, spend time outside in the sunlight during the day.

- Make notes about what happens before sundowning events and try to identify triggers.

- Reduce stimulation during the evening hours. For example, avoid watching TV, doing chores or listening to loud music. These distractions may add to the person’s confusion.

- Offer a larger meal at lunch and keep the evening meal lighter.

- Keep the home well lit in the evening to help reduce the person’s confusion.