- Português Br

- Journalist Pass

Alzheimer’s and dementia: Understand wandering and how to address it

Dana Sparks

Share this:

Wandering and becoming lost is common among people with Alzheimer's disease or other disorders causing dementia. This behavior can happen in the early stages of dementia — even if the person has never wandered in the past.

Understand wandering

If a person with dementia is returning from regular walks or drives later than usual or is forgetting how to get to familiar places, he or she may be wandering.

There are many reasons why a person who has dementia might wander, including:

- Stress or fear. The person with dementia might wander as a reaction to feeling nervous in a crowded area, such as a restaurant.

- Searching. He or she might get lost while searching for something or someone, such as past friends.

- Basic needs. He or she might be looking for a bathroom or food or want to go outdoors.

- Following past routines. He or she might try to go to work or buy groceries.

- Visual-spatial problems. He or she can get lost even in familiar places because dementia affects the parts of the brain important for visual guidance and navigation.

Also, the risk of wandering might be higher for men than women.

Prevent wandering

Wandering isn't necessarily harmful if it occurs in a safe and controlled environment. However, wandering can pose safety issues — especially in very hot and cold temperatures or if the person with dementia ends up in a secluded area.

To prevent unsafe wandering, identify the times of day that wandering might occur. Plan meaningful activities to keep the person with dementia better engaged. If the person is searching for a spouse or wants to "go home," avoid correcting him or her. Instead, consider ways to validate and explore the person's feelings. If the person feels abandoned or disoriented, provide reassurance that he or she is safe.

Also, make sure the person's basic needs are regularly met and consider avoiding busy or crowded places.

Take precautions

To keep your loved one safe:

- Provide supervision. Continuous supervision is ideal. Be sure that someone is home with the person at all times. Stay with the person when in a new or changed environment. Don't leave the person alone in a car.

- Install alarms and locks. Various devices can alert you that the person with dementia is on the move. You might place pressure-sensitive alarm mats at the door or at the person's bedside, put warning bells on doors, use childproof covers on doorknobs or install an alarm system that chimes when a door is opened. If the person tends to unlock doors, install sliding bolt locks out of his or her line of sight.

- Camouflage doors. Place removable curtains over doors. Cover doors with paint or wallpaper that matches the surrounding walls. Or place a scenic poster on the door or a sign that says "Stop" or "Do not enter."

- Keep keys out of sight. If the person with dementia is no longer driving, hide the car keys. Also, keep out of sight shoes, coats, hats and other items that might be associated with leaving home.

Ensure a safe return

Wanderers who get lost can be difficult to find because they often react unpredictably. For example, they might not call for help or respond to searchers' calls. Once found, wanderers might not remember their names or where they live.

If you are caring for someone who might wander, inform the local police, your neighbors and other close contacts. Compile a list of emergency phone numbers in case you can't find the person with dementia. Keep on hand a recent photo or video of the person, his or her medical information, and a list of places that he or she might wander to, such as previous homes or places of work.

Have the person carry an identification card or wear a medical bracelet, and place labels in the person's garments. Also, consider enrolling in the MedicAlert and Alzheimer's Association safe-return program. For a fee, participants receive an identification bracelet, necklace or clothing tags and access to 24-hour support in case of emergency. You also might have your loved one wear a GPS or other tracking device.

If the person with dementia wanders, search the immediate area for no more than 15 minutes and then contact local authorities and the safe-return program — if you've enrolled. The sooner you seek help, the sooner the person is likely to be found.

This article is written by Mayo Clinic Staff . Find more health and medical information on mayoclinic.org .

- Answers to common questions about whether vaccines are safe, effective and necessary Consumer Health: Treating and living with HIV and AIDS

Related Articles

Diseases & Diagnoses

Issue Index

- Case Reports

Cover Focus | June 2022

Wandering & Sundowning in Dementia

Preventive and acute management of some of the most challenging aspects of dementia is possible..

Taylor Thomas, BA; and Aaron Ritter, MD

Alzheimer disease (AD) and related dementias are complex disorders that affect multiple brain systems, resulting in a wide range of cognitive and behavioral manifestations. The behavioral symptoms often have clinical analogs in idiopathic psychiatric disorders and are frequently referred to as neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of dementia. Many therapeutic strategies for NPS are borrowed from treatment of idiopathic psychiatric disorders. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) commonly used to treat major depressive disorder may also be prescribed for depressive symptoms in AD. This strategy has been deemed the “therapeutic metaphor” and has shown varying degrees of success in clinical trials. 1

Clinicians face significant challenges, however, when there is no suitable metaphor to guide treatment for behaviors that emerge solely in dementia. This is particularly problematic for 2 of the most burdensome behavioral manifestations of dementia—sundowning (the worsening of symptoms in the late afternoon and early evening) and wandering. Despite being among the most impactful behaviors in dementia, there is very little research evidence to guide therapeutic approaches. This review provides a brief update of the current literature regarding wandering and sundowning in dementia. Using evidence-based approaches from the research literature, where available, and best practices adopted from our own clinical practice when little evidence exists, we outline a practical treatment algorithm that can be used in the clinic when facing either of these common and problematic behaviors.

Wandering Frequency, Consequences & Causes

Wandering is a complex behavioral phenomenon that is frequent in dementia. Approximately 20% of community-dwelling individuals with dementia and 60% of those living in institutionalized settings are reported to wander .2 Most definitions of wandering incorporate a variety of dementia-related locomotion activities, including elopement (ie, attempts to escape), repetitive pacing, and becoming lost. 3 More recently, the term “critical wandering” or “missing incidents” have been used to draw distinctions between elopement and pacing vs wandering and becoming lost. 4 Critical wandering episodes have a high mortality rate of 20%, placing this symptom among the most dangerous behavioral manifestations of dementia. 5

The risk of wandering increases with severity of cognitive impairment, with the highest rate in those with Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores of 13 or less. 6 Individuals who frequently wander (ie, multiple times per week) almost always have at least moderate dementia. Few studies have compared wandering rates among people with different types of dementia. 7 Experience from our clinical practice suggests that wandering is most common in AD—where spatial disorientation and amnesia are common clinical features—but can also occur in moderate to advanced stages of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Lewy body dementia (LBD). The presence of comorbid NPS (eg, severe depression, sleep disorders, and psychosis) may increase the likelihood of wandering. 8

Causes of wandering are not well understood. Some hypothesize wandering emerges from disconnection among brain regions responsible for visuospatial, motor, and memory functions. A positron-emission tomography (PET) study of 342 individuals with AD, 80 of whom were considered wanderers, found a distinct pattern of hypometabolism in the cingulum and supplementary motor areas among wanderers. Correlations between specific brain regions and the type of wandering (eg, pacing, lapping, or random) were also seen. 9

A relatively larger body of research informs psychosocial perspectives on wandering with 3 scenarios identified in which wandering behaviors commonly emerge, including 1) escape from an unfamiliar setting; 2) desire for social interaction; and 3) exercise behavior triggered by restlessness or lack of activity. Other factors that increase wandering behavior include lifelong low ability to tolerate stress, an individual’s belief that they are still employed at a job, and a repeated desire to search for people (eg, dead family members) or places (eg, a home where they no longer reside). 10

Managing Wandering

There is little empiric evidence to inform treatment approaches to wandering in dementia. Nonpharmaceutical interventions that promote “safe walking” instead of aimless wandering are preferred initial approaches. Several “low tech” options with low associated costs and negligible side effects have some evidence for use, including exercise programs, aromatherapy, placing murals and other paintings in front of exit doors, or hiding door handles. 11 More recently, the explosion of discrete and affordable wearable devices that have global positioning system (GPS) tracking ability have significantly expanded the number of “high-tech” options available to address elopement. These include GPS tagging, bed and door alarms, and surveillance systems. Few have been tested in prospective, placebo-controlled studies, however, making it hard to make firm conclusions regarding efficacy. 12 The ethical implications of using these technologies—including potential infringements on privacy, dignity, and autonomy of individuals—are seldom considered in clinical trials or clinical practice. 13

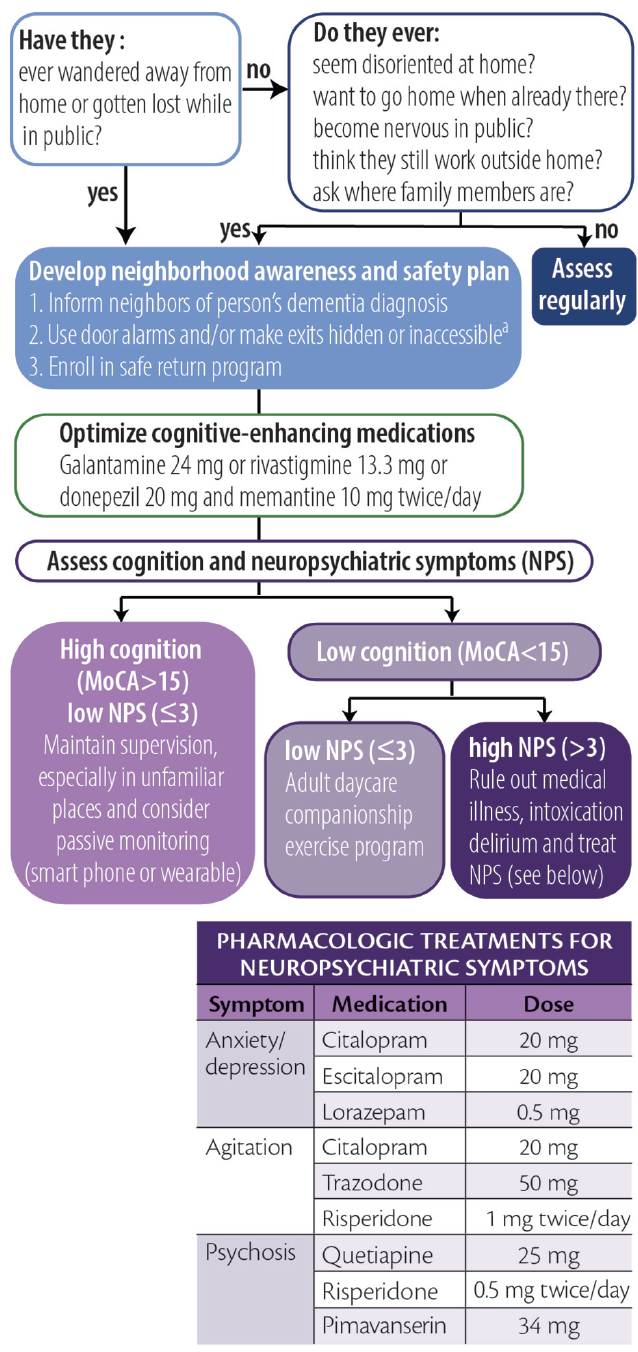

Considering the high prevalence and often deadly consequences associated with wandering, we offer a practical, algorithmic approach to wandering in dementia (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Algorithmic approach to wandering. Abbreviation: MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment. a Persons with dementia should never be left alone behind locked doors.

Click to view larger

Screening for Wandering

To screen for wandering behavior, we ask the following 2 questions of or about all persons with dementia:

1. Have they ever wandered away from their home?

2. Have they ever gotten lost while in public?

If either of these are responded to affirmatively, we make recommendations and stratify risk as described below. If both questions are responded to with “no,” we ask if they:

1. ever seem disoriented at home or in familiar places?

2. ever report a desire to go home even while at home?

3. become excessively nervous while in public?

4. talk about needing to fulfill prior work obligations?

5. ask about the whereabouts of past family or friends?

An affirmative answer to any of these 5 questions may indicate an increased risk for wandering. For those who wander or are at high risk for wandering we provide basic education, recommend increased diligence, and maximize behavioral strategies to improve orientation (eg, display a written calendar and/or a large digital clock with time and date and optimize use of cognitive-enhancing agents when appropriate).

Creating a Wandering Safety Plan

Once a wandering event has occurred, we recommend families develop a neighborhood awareness and safety plan. The Alzheimer’s Association’s website has excellent resources devoted toward developing this plan ( https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering ). At a minimum, the safety plan should include notifying neighbors that the person has dementia, keeping a list of places they are likely to wander to, and having a recent photo readily available for emergency medical and other services. We also educate families about the initial steps to take if wandering occurs, including immediately searching areas favoring the direction of the dominant hand, focusing the search within 1.5 miles of the home, and calling 9-1-1 no more than 15 minutes after a person with dementia has been determined to be missing. Additional recommendations include obtaining medical identification jewelry, installing door alarms, and making locks inaccessible (ie, hiding them or placing them out of reach). Families should be encouraged to enroll in a safe return program (eg, MedicAlert, Project Lifesaver, or Silver Alert) if one is available in their area. It is important to note that people with dementia should never be locked by themselves inside a home.

Managing Risk by Stratified Wandering Type

Cluster analyses show people who wander can largely be grouped into 1 of 3 different types based on cognitive and behavioral characteristics. 14 These groupings are useful for tailoring interventions and can be identified for an individual with combined cognitive test scores and behavioral symptom profiles. We use the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) 15 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q) 16 because they are relatively quick to administer while providing important information and can be simultaneously administered to caregivers (NPI-Q) and patients (MoCA). These assessments can be used to stratify patients as follows.

Group 1: High Cognitive Function, Low Behavioral Disturbances. Individuals who score greater than 15 on the MoCA and have 3 or fewer behavioral symptoms wander infrequently (<1 time/month) and often only in unfamiliar settings. Because wandering is usually triggered by unexpected stressors, the main goal for these individuals is to provide adequate supervision in unfamiliar settings. Those in this group may also still carry a mobile phone with several high-tech options (eg, GPS systems or “find my phone” apps) that may be beneficial.

Group 2: Low Cognitive Function, Low Behavioral Disturbances. Persons with lower cognitive test scores (eg, ≤10 on the MoCA) and fewer than 3 NPS may wander because of boredom or a lack of physical or cognitive stimulation. For this group, we recommend a companion caregiver or adult daycare program to engage the patient in enjoyable activities and incorporate supervised walks or exercise programs during the day. Individuals in this group may benefit from the creation of an outdoor area that may be explored safely.

Group 3: Low Cognitive Function, High Behavioral Disturbances. People in this group require the most proactive approaches because they are likely to be the most frequent wanderers and may be at highest risk for dangerous outcomes. Wandering in this group may be driven by delusions, particularly the persecutory type. 8 We recommend, as a first step, determining whether other factors such as pain, delirium, or intoxication may be contributing to the person’s NPS. If no additional etiologies can be clearly identified, comorbid NPS should be addressed with best clinical practices, borrowing heavily from psychiatry with the “therapeutic metaphor” (See Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia in this issue). Many in this group may require institutionalization or constant supervision from hired caregivers to prevent harm. Nonpharmacologic strategies recommended for this group include taping a 2-foot black threshold in front of each door to serve as a visual barrier, installing cameras and warning alarms for outward facing doors, and installing safety gates around the house.

Sundowning Frequency, Consequences & Causes

Sundowning is the term used to describe the emergence or intensification of NPS occurring in the early evening. This phenomenon, thought to be unique to people with dementia, has long been recognized by researchers and caregivers as being among the most challenging elements of dementia care. 17 Although most frequently seen in AD, sundowning has also frequently been observed in other forms of dementia. Sundowning is among the most common behavioral manifestations of dementia, with rates in institutionalized settings exceeding 80%. 18 The risk of sundowning increases in moderate and severe dementia and because of its close association with sunlight, is more common in the autumn and winter seasons. 19

The impact of sundowning on persons with dementia is immense. Sundowning is among the most common reasons for institutionalization and is associated with faster rates of cognitive decline and increased risk for wandering. 17 Sundowning also increases care partner stress, which, in turn, may increase risk for agitation in patients. 18

The causes of sundowning are likely multifactorial. Sundowning is commonly linked to alterations in circadian rhythms. 19 Autopsy studies of people who had AD show a disproportionate loss of neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which regulates the release of melatonin in response to light. 20 Other research links sundowning to reductions in cholinergic neurotransmission, 21 and at least 1 study showed increased levels of cortisol, which may suggest alterations of the entire hypothalamic-pituitary axis. 21 Sleep disruption, inadequate sunlight exposure, and disrupted routines increase the likelihood of sundowning. 17 Medications with anticholinergic properties and sedatives may also exacerbate sundowning.

Management of Sundowning

The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model provides a framework for understanding and managing sundowning. 22 In this model, sundowning occurs because diurnal alterations in circadian rhythms temporally correlate with increases in pain, hunger, or fatigue that occur later in the day. Disruptions in emotional regulation emerge when a person’s ability to tolerate such stressors is exceeded.

As with wandering, there is little empiric evidence to guide pharmacologic management of sundowning. Melatonin has been studied in several open-label studies and case series with varying levels of success. 23 Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine reduce agitated behaviors, but have not been studied for management of sundowning. 24 Nonpharmacologic interventions (eg, eliminating daytime naps, increasing sunlight exposure, aerobic exercise, and playing music) can reduce sundowning, 17 but it is difficult to make firm conclusions about the efficacy of these measures because most have not been evaluated in prospective, placebo-controlled studies.

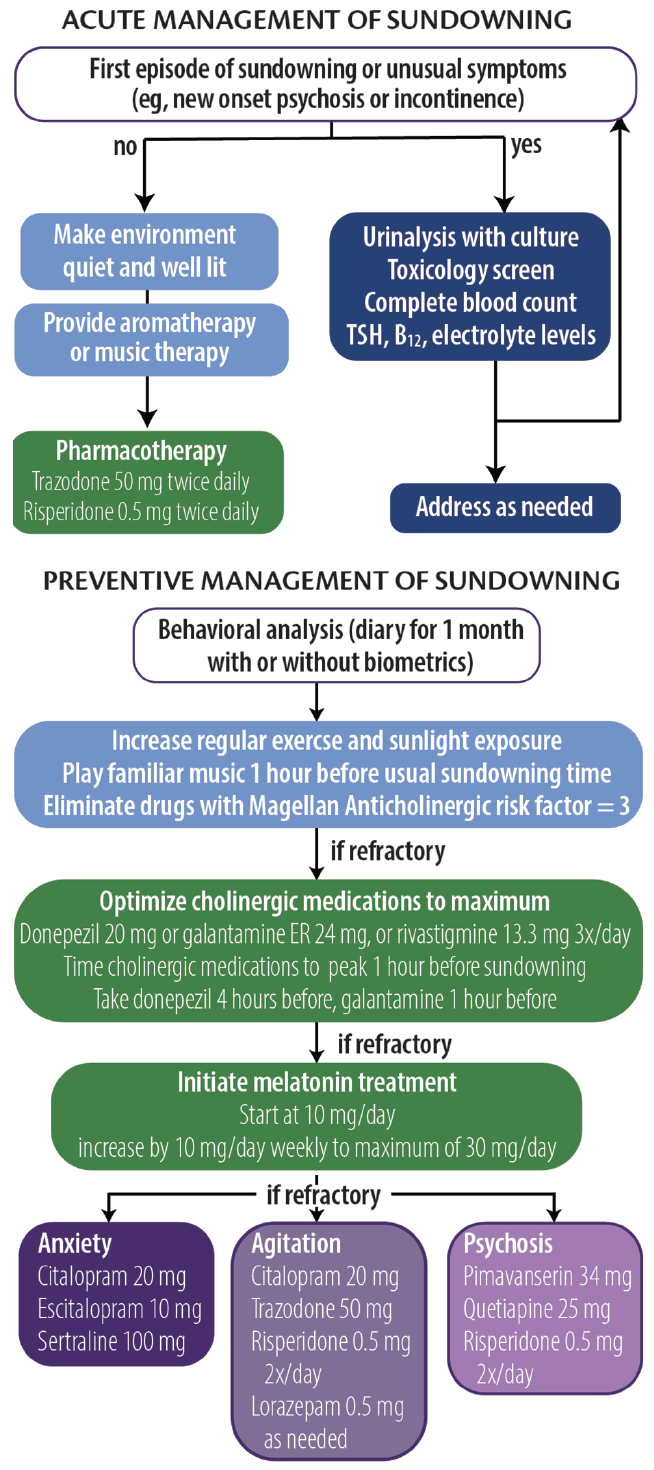

Analogous to headache management, approaches to sundowning can be broadly categorized as acute or preventive (Figure 2). Although preventive approaches may be more effective, caregivers may be able to reduce NPS associated with sundowning when it occurs.

Figure 2. Acute and preventative approaches to sundowning. Abbreviation: TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Acute Management

The PLST model can be used to identify any and all triggers that may contribute to sundowning episodes. For a first or unusual episode, it is recommended that a targeted medical and laboratory evaluation including urine culture, complete blood count, drug toxicology, and levels of electrolytes, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and vitamin B 12 be obtained. During an episode, whenever possible, a quiet, well-lit environment should be provided. Aromatherapy and familiar music at a medium volume may also help reduce anxiety and agitation. For persons at risk of hurting themselves or others, a low-dose psychotropic medication (eg, trazodone 50 mg repeated 1 hour later followed by risperidone 0.5 mg) may be necessary.

Preventive Management

In our clinical experience, prevention strategies may reduce the severity and frequency of sundowning. The first step is to conduct a behavioral analysis of the sundowning behavior. We recommend a daily journal be maintained for at least 1 month to document the types of behavior (eg, agitation, anxiety, psychosis, and disorientation) that occur, time of onset, and any extenuating circumstances that may have contributed to episodes of sundowning. Care partners can also provide information regarding medication administration and sleeping behavior to inform the analysis. The health care professional should analyze the journal, looking for patterns and correlations with other factors (eg, shift changes at care homes or changes to daily routines). The journal can be supported by biometric data from wearable technologies that provide objective measures of physical activity and sleep, which can be helpful in tailoring both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches.

We also recommend increasing the amount of regular exercise and sunlight exposure, preferably in the early afternoon. Caregivers are advised to start playing soothing or familiar music approximately 1 hour before sundowning behavior typically starts. Any medication with Magellan Anticholinergic Risk Scale scores of 3 should be eliminated, which requires scrutiny of medication lists. 25 Optimization of cognitive-enhancing medication doses and timing administration such that mean peak plasma concentrations are reached 1 hour before a person’s typical time of sundowning behavior may be beneficial.

If problematic sundowning behavior still persists, we recommend melatonin supplementation at an initial dose of 10 mg taken at nighttime, followed by a weekly increase by 10 mg to a maximum dose of 30 mg. This regimen is instituted regardless of reported sleep quality. If symptoms persist, the next step is to target NPS based on the individual’s most recent NPI-Q profile. The mantra of “start low and go slow” should guide therapeutic interventions, waiting at least 2 weeks before altering doses. In general, antidepressants are preferred first steps unless safety concerns necessitate more proactive approaches.

1. Cummings J, Ritter A, Rothenberg K. Advances in management of neuropsychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Psychiatry Rep . 2019;21(8):79.

2. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Nuti A, Danti S. Wandering and dementia. Psychogeriatrics . 2014;14(2):135-142.

3. Algase DL, Moore DH, Vandeweerd C, Gavin-Dreschnack DJ. Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging Ment Health . 2007;11(6):686-698.

4. Petonito G, Muschert GW, Carr DC, Kinney JM, Robbins EJ, Brown JS. Programs to locate missing and critically wandering elders: a critical review and a call for multiphasic evaluation. Gerontologist. 2013;53(1):17-25.

5. Rowe MA, Vandeveer SS, Greenblum CA, et al. Persons with dementia missing in the community: is it wandering or something unique? BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:28.

6. Hope T, Keene J, McShane RH, Fairburn CG, Gedling K, Jacoby R. Wandering in dementia: a longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr . 2001;13(2):137-147.

7. Ballard CG, Mohan RNC, Bannister C, Handy S, Patel A. Wandering in dementia sufferers. Int J Geriat Psychiatry . 1991;6:611-614.

8. Klein DA, Steinberg M, Galik E, et al. Wandering behaviour in community-residing persons with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry . 1999;14(4):272-279.

9. Yang Y, Kwak YT. FDG PET findings according to wandering patterns of patients with drug-naïve Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Neurocogn Disord . 2018;17(3):90-99.

10. Hope RA, Fairburn CG. The nature of wandering in dementia: a community-based study. Int J Geriat Psychiatry . 1990;5(4):239-245.

11. Neubauer NA, Azad-Khaneghah P, Miguel-Cruz A, Liu L. What do we know about strategies to manage dementia-related wandering? A scoping review. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:615-628.

12. Neubauer NA, Lapierre N, Ríos-Rincón A, Miguel-Cruz A, Rousseau J, Liu L. What do we know about technologies for dementia-related wandering? A scoping review: Examen de la portée: Que savons-nous à propos des technologies de gestion de l’errance liée à la démence? Can J Occup Ther. 2018;85(3):196-208.

13. O’Neill D. Should patients with dementia who wander be electronically tagged? No. BMJ. 2013;346:f3606.

14. Logsdon RG, Teri L, McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Kukull WA, Larson EB. Wandering: a significant problem among community-residing individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(5):P294-P299.

15. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(9):1991]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

16. Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci . 2000;12(2):233-239.

17. Canevelli M, Valletta M, Trebbastoni A, et al. Sundowning in dementia: clinical relevance, pathophysiological determinants, and therapeutic approaches. Front Med (Lausanne) . 2016;3:73.

18. Gallagher-Thompson D, Brooks JO 3rd, Bliwise D, Leader J, Yesavage JA. The relations among caregiver stress, “sundowning” symptoms, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(8):807-810.

19. Madden KM, Feldman B. Weekly, seasonal, and geographic patterns in health contemplations about sundown syndrome: an ecological correlational study. JMIR Aging 2019;2(1):e13302. doi:10.2196/13302

20. Wang JL, Lim AS, Chiang WY, et al. Suprachiasmatic neuron numbers and rest-activity circadian rhythms in older humans. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(2):317-322.

21. Weinshenker D. Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res . 2008;5(3):342-345.

22. Smith M, Gerdner LA, Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. History, development, and future of the progressively lowered stress threshold: a conceptual model for dementia care. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2004;52(10):1755-1760.

23. Cohen-Mansfield J, Garfinkel D, Lipson S. Melatonin for treatment of sundowning in elderly persons with dementia - a preliminary study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr . 2000;31(1):65-76.

24. Gauthier S, Feldman H, Hecker J, et al. Efficacy of donepezil on behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(4):389-404.

25. Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med . 2008;168(5):508-513.

TT reports no disclosures AR's work on this paper was supported by NIGMS P20GM109025

Taylor Thomas, BA

University of Nevada-Las Vegas School of Medicine Las Vegas, NV

Aaron Ritter, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Neurology Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Las Vegas, NV

Treating Dementias With Care Partners in Mind

Dylan Wint, MD

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia

Jeffrey L. Cummings, MD, ScD

This Month's Issue

Jill R. Baron, MD; and Jennifer Villwock, MD

Swati Pradeep, DO; and Jaime M. Hatcher-Martin, MD, PhD

Matthew C. Varon, MD; and Mazen M. Dimachkie, MD

Related Articles

Abdalmalik Bin Khunayfir, MD; and Brian Appleby, MD

Simon Ducharme, MD, MSc, FRCPC

Sign up to receive new issue alerts and news updates from Practical Neurology®.

Related News

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Alzheimers Dement (Amst)

What do we know about strategies to manage dementia-related wandering? A scoping review

Noelannah a. neubauer.

a Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Peyman Azad-Khaneghah

Antonio miguel-cruz.

b School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia

Associated Data

Three of five persons with dementia will wander, raising concern as to how it can be managed effectively. Wander-management strategies comprise a range of interventions for different environments. Although technological interventions may help in the management of wandering, no review has exhaustively searched what types of high- and low-technological solutions are being used to reduce the risks of wandering. In this article, we perform a review of gray and scholarly literature that examines the range and extent of high- and low-tech strategies used to manage wandering behavior in persons with dementia. We conclude that although effectiveness of 49 interventions and usability of 13 interventions were clinically tested, most were evaluated in institutional or laboratory settings, few addressed ethical issues, and the overall level of scientific evidence from these outcomes was low. Based on this review, we provide guidelines and recommendations for future research in this field.

- • Twenty categories of high and low-tech wander-management strategies were identified.

- • Most strategies were only evaluated in institutional or laboratory settings.

- • Overall level of scientific evidence from the outcomes of these strategies was low.

- • Research is required to demonstrate the efficacy of high- and low-tech strategies.

1. Introduction

The rates of cognitive impairment are on the rise worldwide as our world population ages. In 2016, 46.6 million people globally were living with dementia, and this number is projected to increase to 75 million by 2030 [1] . As a result, the already high economic burden of $818 billion in 2015 has been estimated to have increased to $1 trillion by 2018. These staggering numbers have led to the establishment of more than 30 national dementia strategies worldwide as nations begin to work together to transform dementia care and support [2] .

One significant concern for persons with dementia and their family caregivers is becoming lost when alone or in unfamiliar environments [3] , [4] . This behavior is often indicative of wandering. Wandering has been defined as “a syndrome of dementia-related locomotion behavior having repetitive, frequent, temporally disoriented nature that is manifested in lapping, random, and/or pacing patterns some of which are associated with eloping, eloping attempts, or getting lost unless accompanied” [5] . It can be either an aimless or purposeful behavior [5] , and its severity can be affected by rhythm disturbances [6] , spatial disorientation and visual-perceptual deficits [7] , physical [8] and social [9] environments, or changes in personality and behavior patterns [10] . A more recent definition of wandering also includes critical wandering, the type of wandering that results in older adults to elope with no orientation to time and place. Indeed, critical wandering is what exposes persons with dementia to the potential dangers that is of concern to caregivers [11] .

More than 60% of persons with dementia will wander. The consequences of wandering vary from minor injuries [12] , to high search and rescue costs and death [13] . If not found within 24 hours, up to half of those who wander and get lost will suffer serious injury or death [14] . Wandering behavior also significantly impacts the care and economic burden of family caregivers. For example, caregivers have been found to experience increases in emotional distress and potential civil tort claims and regulatory penalties [15] . The severity of these outcomes has gained attention from caregivers and first responders alike [16] and raises questions about how the adverse outcomes associated with wandering can be managed, and whether managing this behavior can have an influence on improving the stressors that result from caring for a person with dementia [17] .

Early interventions to manage wandering included physical restraints and medications [18] ; however, use of such strategies have been in decline due to unwanted side effects [19] and negative consequences such as poor physical and social functioning [20] . High tech strategies, such as wearable global positioning system (GPS)–enabled devices [21] , and low-tech strategies, such as visual barriers [22] , offer options for mitigating risks while allowing a person with dementia with a degree of autonomy. These strategies may therefore be a preferred approach over restraints and medications [23] . Wander-management technologies may extend the time a person with dementia can live in a community and provide peace of mind to caregivers [21] , [22] , [24] . Although such strategies are more available to consumers, only one review [25] has been conducted to examine what existing interventions for wandering are being used, and whether their effectiveness has been tested in laboratory or community settings. This review, however, only included high-tech solutions, excluding several key strategies, such as door murals and distractions, which may also help with managing this behavior. Although that review presents state of the evidence to support these interventions, it excluded potential vital reviews and studies that fall outside of this focus, limiting the scope of all available solutions within the scholarly and gray literature.

The current review serves as an extension from Neubauer et al. [25] where only high-tech solutions used to manage dementia-related wandering behavior, and only studies evaluating their usability or effectiveness were included. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to identify the range and extent of all wander-management strategies, their product readiness level, and all associated outcomes. This information provides evidence for caregivers and clinicians when they select strategies to manage wandering in persons living with dementia.

2. Methodology

2.1. design.

This is a scoping literature review based on Daudt, van Mossel, and Scott's (2013) [26] modification of Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) [27] methodology. The original Arksey and O'Malley's methodology [27] includes six steps: (1) determine the research question; (2) identify the applicable studies; (3) study selection; (4) chart data; (5) collect, summarize, and report the results; and (6) consultation exercise (optional). Daudt, van Mossel, and Scott's (2013) [26] modification of this methodology involves an interprofessional team in step (2), and in step (3) uses a three-tiered approach to cross-check and select the articles.

2.2. Data sources and search strategy

We examined peer-reviewed and gray literature published between January 1990 and November 2017. Peer-reviewed literature studies were searched in six databases: EMBASE, CINAHL, Ovid Medline, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Scopus. These databases were searched using the following terms identified in the title, abstract, or key words: (physical barrier* OR barrier* OR lock* OR low tech* OR nonpharmacological OR therap* OR exercise OR distraction OR pet therap* OR home modification* OR door mural* or signage OR identification information OR ID card* OR bracelet* OR jewelry OR technolog* OR gerontechnology OR telemonitoring OR telesurveillance OR telehealth OR assistive technology OR GPS OR sensor* OR mobile device OR application OR apps OR radio frequency telemetry OR radio frequency identification OR tracking OR surveillance OR alarms OR tagging OR electronic OR restraints) AND (wander* OR walk* OR sundowning OR escape OR restlessness OR pacing OR exit* OR missing OR stay OR benevolent wandering OR critical wandering OR non-critical wandering) AND (dementia OR Alzheimer's Disease OR cognitive disorders). Gray literature was searched in eight databases: Google, CADTH grey matters, Institute of Health Economics, Clinicaltrials.gov , The University of Alberta Grey Literature Collection, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, National Guidelines Clearinghouse, and Health on the NET Foundation were searched for strategies developed to address wandering in persons with dementia—(dementia) AND (wander* OR elope OR sundowning OR critical wandering OR benevolent wandering OR non-critical wandering) (nonpharmacological OR therap* OR exercise OR distraction OR low tech* OR home modification OR technology OR tech* OR GPS OR RFID OR mobile applications OR iOS OR android OR wifi) ( Appendix A ).

2.3. Studies selection process

Articles were exported to a reference manager where duplicate articles were excluded. Two authors (N.A.N. and P.A.-K.) first screened the titles and abstracts, reviewed the full text of all potential articles, and extracted the data ( Fig. 1 ). Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Where disagreements were unresolved, the third reviewer (A.M.C.) provided input. To determine agreement between raters, 20% of the selected articles were extracted and compared. The level of agreement between the raters was high, that is, average agreement for abstracts 96% (298/310) (average κ score of 0.87, P < .000), and 97% (198/204) average agreement for full papers (overall κ score of 0.91, P < .000). For included articles, reviewers first extracted author initials, citation, and whether the study was eligible for review. If a study was considered ineligible for data extraction, the reason for exclusion was reported ( Fig. 1 ).

Scholarly reviewed literature article search results.

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

- a. address wander-management strategies in the home or supportive care environments for persons with dementia or cognitive decline regardless of whether it was embedded in an environment, was worn, or was implemented as a form of therapy.

- b. address critical or noncritical wandering in older adults with dementia.

- c. include strategies that support independence and address outcomes associated with wandering, regardless of level of development.

- 2. Clinically oriented studies that included only persons with dementia over age 50 years.

- 3. Studies published in any language and available in full text in peer-reviewed journals or conference proceedings from electronic abstract systems.

- 4. Studies that used any type of study design or methodology, with positive or negative results.

- 5. Studies that used lower and higher complexity technologies for wander management such as GPS and door murals.

- 6. Studies published in books or book chapters and conference proceedings.

- 7. For gray literature: were websites suggesting or selling strategies to address dementia-related wandering.

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

- 1. Abstracts or studies that were not available.

- 2. Publications that did not provide adequate information for categorizing the study (e.g., participant characteristics).

2.4. Bias control

The procedure of Neubauer et al. [25] was followed to address bias. By including any language, multiple databases, and data types, we conducted a thorough search, to achieve a high level of sensitivity [28] . Inclusion of studies with positive and negative results addressed publication bias [29] . Inclusion of studies registered in electronic abstract systems served as the first “ quality filter ” and ensured a degree of scientific level of conceptual methodological rigor [30] . Studies published before 1990 were not included because most development of wander-management strategies occurred later [17] , [31] . The use of two pairs of raters during the selection for relevant articles, and a third and fourth rater when there was disagreement, minimized rater-bias that may have arisen from the subjective nature of applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.5. Publications review and data abstraction

Peer-reviewed articles were examined for the following attributes: features of wander-management strategies (i.e., strategy type, specifications, cost, product readiness level) and characteristics of research (i.e., clinical implications, sample size, participant characteristics, level of clinical evidence of outcomes). Gray literature was reviewed for features of wander-management strategies (i.e., strategy type, specifications, cost, device features). Two raters individually extracted data from articles.

2.5.1. Features of wander-management strategies

- (a) Strategy type. Refers to the name and strategy used to manage wandering. Primary categories identified include high tech [32] (e.g., locating, alarms/surveillance, wandering detection, wayfinding belt, distraction/redirection, and locks/barriers) and low tech [32] (e.g., exercise, distraction/redirection, locks/barriers, physical restraints, community, signage, wayfinding, supervision, education, and other).

- (b) Product readiness level (PRL). Assesses the maturity of evolving products during their development. We used the PRL [33] in which nine levels are used and ranged from PRL1 (basic principles observed) to PRL9 (actual system proven in operational environment).

2.5.2. Characteristics of research conducted in wander-management strategies

- (a) Type of study, design of the study, level of clinical evidence, and outcomes in the studies regarding wander-management strategies. Studies were classified into four types, including strategy- and clinical-oriented studies, usability, program-oriented, review, or a combination of them. Study design was categorized using the McMaster assessment of study appraisal [34] , [35] . An adaptation of the modified Sackett criteria proposed by Teasell et al., (2013) [36] was used to determine the level of evidence provided by the clinical-oriented studies. Using this criterion, raters assigned a level of evidence for a given technological intervention based on a seven-level scale. Quality of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was measured by the Physiotherapy Evidence Database ( PEDro ) scale [37] . The PEDro scale has 11 criteria, 10 being the maximum score that a trial can achieve. Scores of 9–10 are considered “excellent” quality; 6–8 indicates “good” quality; 4–5 are “fair” quality; and below 4 is “poor” quality [38] . As the field of wander-management technologies is diverse, we assessed the levels of evidence across three device categories: mobile locator, sensor and alarm, and wayfinding. Data on sample size, experiment length, study strategy (i.e., clinical, usability, combined), study design (i.e., qualitative or quantitative research method), main outcomes of the study, and data collection location (i.e., home, community, facility) were collected.

- (b) Ethical concern associated with the implementation of the wander-management strategy. Refers to the ethical concerns that were addressed regarding the implementation or use of the wander-management strategy. Examples of concerns include but not limited to protecting privacy, dignity, and autonomy of the person with dementia.

2.6. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted by one person (N.A.N.). Due to the diversity of the included articles, a qualitative approach was used, where content analysis was performed on the extracted data highlighted (in bold) previously. Descriptive statistics (i.e., averages and standard deviations [SDs]) were calculated for diversity of the technology specifications, strategy cost, and PRL across the included wander-management strategies, in addition to participant age, number of participants from the included studies, and study length.

The initial search identified 4096 peer-reviewed studies; 118 studies were included in the data-abstraction phase and final analysis (2.9%, 118/4096) ( Fig. 1 ). Most studies (68.6%, 59/86) were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria 1a, 1b, 1c, or all three. Other reasons for exclusion from the final data-abstraction phase were that studies were not available (31.4%, 27/86).

For the gray literature, 130 strategies from 44 commercial websites, 1 dissertation website, 5 self-help websites, 8 Alzheimer's-specific websites, and 1 online magazine were included in the data-abstraction phase and final analysis. All met inclusion criteria (7), that is, were websites suggesting or selling strategies to address dementia-related wandering.

Studies containing high-tech–only strategies were characterized by low journal impact factor (i.e., Source Normalized Impact per Paper mean 0.94, SD 0.59; 95% confidence interval [0.79, 1.08]) and were published in journals located in Q1 (13 studies), Q2 (16 studies), Q3 (5 studies), and Q4 (6 studies) journal quartile per SCImago Journal Rank classification [39] . Studies containing low-tech–only strategies were characterized by low journal impact factor (i.e., Source Normalized Impact per Paper mean 0.99, SD 0.51; 95% confidence interval [0.84, 1.14]) and were published in journals located in Q1 (19 studies), Q2 (16 studies), Q3 (6 studies), and Q4 (2 studies) journal quartile per SCImago Journal Rank classification [39] . Studies containing both high- and low-tech strategies were characterized by low journal impact factor (i.e., Source Normalized Impact per Paper mean 0.99, SD 0.82; 95% confidence interval [0.58, 1.40]) and were published in journals located in Q1 (4 studies), Q2 (7 studies), and Q3 (1 studies) journal quartile per SCImago Journal Rank classification [39] .

Regarding design [34] , [35] , seven high-tech studies were of qualitative design [phenomenology (4) and grounded theory (3)], 21 were of quantitative design [cross-sectional design (10), single-case design (4), case study (3), before-after design (1), randomized controlled trial (1), randomized pre-post (1), and descriptive (1)], and 9 were reviews [systematic review (4) and other review (5)]. Low-tech strategies included two studies that were of qualitative design [grounded theory (2)], 14 were of quantitative design [cross-sectional design (4), case study (4), single-case design (2), retrospective (1), pretest-posttest (1), ABA descriptive design (1), and randomized controlled trail (1)], and 17 were reviews [systematic review (10), Cochrane review (1), and other review (6)]. Publications containing both high- and low-tech strategies included two studies that were of qualitative design [phenomenology (2)], 4 were of quantitative design [cross-sectional design (1), single-case design (1), randomized controlled trail (1), and case study (1)], and 4 were reviews [systematic review (2), Cochrane review (1), and other review (1)] ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

Positive and negative outcomes per type of strategy (high tech vs. low tech) (n = 118) of scholarly literature

NOTE. Three of 61 high-tech, 8/42 low-tech, and 2/15 articles that contained both high- and low-tech strategies did not evaluate the effectiveness of wander-management strategies and only proposed potential strategies. Therefore, outcomes of these included articles could not be provided. Level of evidence according to Sackett criteria proposed by Teasell et al. [36] .

Included peer-reviewed literature came from 20 countries, with over half of the studies being conducted in the USA (58%, 47/118) and the UK (16%, 19/118). Similarly, for the gray literature, strategies were found to originate from 7 countries, with almost 80% of the technologies being from the USA and UK (75% USA, 12% Canada, and 7% UK). Publication year of the included peer-reviewed literature varied, with wander-management strategy publications appearing in the early 1990s, and the total number of publications increasing over the last 27 years. A trend was evident pertaining to the type of strategy being published, where there has been a predominant focus on high- versus low-tech strategies over the last decade.

3.1. Features of wander-management technologies

3.1.1. wander-management strategy—type used and strategy specifications.

A total of 183 high-tech strategies (109 from peer-reviewed and 74 from gray literature) and 143 low-tech strategies (85 from peer-reviewed and 58 from gray literature) were included in this scoping review and included 6 subcategories of high-tech strategies and 14 subcategories of low-tech strategies. The most commonly used high-tech subcategories from the scholarly literature were locating strategies (i.e., GPS, radio frequency, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi; 71.6%, 78/109) and alarm and sensors (i.e., motion and occupancy sensors, monitors, and optical systems; 19.3%, 21/109). The most commonly used high-tech subcategories from the gray literature were also locating technologies (i.e., GPS and radio frequency; 63.5%, 47/74) and alarm and sensors (i.e., motion sensors; 35.1%, 26/74) ( Fig. 2 ). The most commonly used low-tech subcategories from the scholarly literature were distraction/redirection strategies (i.e., doll therapy, music therapy, mirrors in front of exit doors, visual barriers such as cloth on exit doors or door murals, and the integration of purposeful activities such as chores and crafts; 35.3%, 30/85), exercise groups (i.e., walking; 12.9%, 11/85), and identification strategies (i.e., ID cards, labels, and the Safe Return Program; 8.2%, 7/85) ( Fig. 2 ). The most commonly used low-tech subcategories from the gray literature were distraction/redirection strategies (i.e., visual barriers, planning meaningful activities, animal therapy; 25.9%, 15/58), locks/barriers (i.e., door locks; 15.5%, 9/58), and identification strategies (i.e., Safe Return and Medic Alert; 12.1%, 7/58) ( Fig. 2 ).

Number of strategies that were high (n = 183) and low (n = 142) tech.

3.1.2. Product readiness level

For the peer-reviewed articles, two were in the analytical and experimental critical functions phase (PRL3), and 21 were either in development and testing phases in laboratory, or validated in relevant environments (PRL 4 and 5), or the technologies were in demonstration or pilot phase (PRL6). The remaining 31 articles contained strategies either prototypes near or planned in an operational system or were mature strategies in which actual systems operated over the full range of expected conditions (PRL9) ( Table 1 ). A total of 19 high-tech articles, 34 low-tech articles, and 11 articles containing both high- and low-tech strategies could not be classified using the PRL scale. Primary reasons were due to the high number of review articles included in this study, in addition to many strategies that were proposed but not evaluated. Articles containing both high- and low-tech solutions were found to have the highest technology readiness level (PRL9), in comparison with high-tech–only articles with an average PRL7 and low-tech–only strategies with an average PRL7.

3.2. Descriptive analysis of studies

3.2.1. characteristics of the research conducted in wander-management technologies.

- (a) Participant characteristics, sample size, length, and location of included studies. Participants of the included studies had a mean age of 75 years (SD 9.7). The age ranged from 23 to 90 years for caregivers and 60 to 103 years for persons with dementia, with a high dispersion in the number of participants (i.e., mean of n = 217 and SD = 77.2). Although all peer-reviewed articles included persons with dementia, only 19 articles (16%, 19/118) specified their underlying degree of dementia and level of cognitive decline. Almost 43% (38/88) of the included clinically oriented studies were small trials with a total number of participants less than 50 (i.e., mean of n = 10.8; SD 10.0), whereas the remaining trials can be described as medium-large (i.e., >50) with a mean of n = 200.5 (SD 338.0). No mean differences were found across low- and high-tech strategy studies for small and medium-large trials ( P > .05). Of the 88 included clinical studies, 29 did not report sample size and therefore were not included in the aforementioned calculations. Fourteen studies involved caregivers; however, only seven reported the relationship between the individual with dementia and caregiver. The most common type of family caregiver was a combination of children and spouse (18.6%), followed by spouse only (17.7%), and children (16.7%). Professional caregivers, search and rescue workers, and nurses were also included, making up nearly half of the reported involved stakeholders (40.3%). Forty-three of the studies reported the ratio of male-to-female dementia clients and caregivers. The average total number of females included in this review was 60 (SD 27), whereas the average total number of males included in this review was 39 (SD 36). Only 11 of the 118 studies reported ethnicity of participants. Of these, two were 100% Caucasian, five were more than 70% Caucasian, four were 100% Asian, and five contained <25% for Latino, African American, and African Caribbean decent. The lengths of the included studies varied (mean 4.8 months; SD 11.5). Only 57 of the 118 studies (48%) reported the location of the study. The setting of tests for the included studies ranged from long-term care (43.9%), community (26.3%), laboratory (10.5%), home (7.0%), hospital (5.3%), assisted living (3.5%), and outdoor environments (3.5%).

Table 2

High-tech main outcomes of scholarly literature

Abbreviations: RFID, radio-frequency identification; GPS, global positioning system; RF, radio frequency.

The outcome variables for low-tech strategies included wandering prevalence/frequency, attempted door testing/exiting/entries, total time seated, number of aggressive events, restlessness, and success facilitating return of the missing person ( Table 3 ). For the measures used to assess the proposed outcome variables, 17 measures were reported, and of these, 76% (13/17) were different. The most commonly used approaches were time between door testing/exiting (4/17) and observations (3/17). Finally, the outcome variables for studies that included low- and high-tech strategies included effectiveness of the intervention, experience and advise using the different strategies, acceptability related to the intervention, distance of wandering, and agitation and irritability ( Tables 2 and and3). 3 ). For the measures used to assess the proposed outcome variables, 16 measures were reported, and of these, 88% (14/16) were different. The most commonly used approaches were interviews (2/16) and observations (2/16).

Table 3

Low-tech main outcomes of scholarly literature

For the overall outcomes, 48.3% (57/118) of the included peer-reviewed literature showed advantages of wander-management strategies in terms of managing wandering in persons with dementia. Forty-eight of the 118 studies reported negative or nonsignificant differences, but positive versus negative outcomes were not significantly different ( P > .05). When separating the number of positive and negative or mixed outcomes by technology complexity, 52% (32/61) of the high-tech strategies, 50% (21/42) of the low-tech strategies, and 27% (4/15) of the studies that included both low- and high-tech strategies demonstrated positive results. Thirteen studies did not include results that evaluated wander-management strategies; therefore, they were not included in calculations. The above indicates that although the implementation of strategies to manage the adverse outcomes associated with wandering is promising, there is significant room for improvement and requires further investigation. Table 1 shows the number of studies classifying the positive and negative outcomes per device type, in addition to details on the total number of participants and study design types.

- (c) Evidence of the clinical outcomes. The level of scientific evidence of the clinical-oriented studies that evaluated wander-management strategies using quantitative methods was low. Regarding the level of scientific evidence for the studies that evaluated high-tech strategies, only one article incorporated an RCT design [13] ; however, details were not explained. Ten papers used a cross-sectional design. All studies were at a level of evidence 5, and results indicated that high-tech strategies have great potential for locating the wanderer quickly; however, many devices do not follow to their claims, which could in part be due to the low quality of effectiveness testing. GPS locating devices consistently demonstrated superior accuracy to radio frequency devices. Family caregivers were perceived significantly more important in the decision-making process than figures outside of the family. Four studies used a single-case study design without a baseline phase, also at a level of evidence 5, indicating that individuals with mild dementia are capable of following vibrotactile signals, that wandering detection devices can contribute toward improved safety by identifying attempts to elope by setting up alarms and sensors, and that locating devices demonstrate promise as a novel and competent healthcare approach in the case of dementia scenarios. Seven studies used qualitative approaches, which cannot be assessed using Sackett's criteria [36] .

Regarding low-tech strategies, only one study incorporated an RCT design. This RCT [40] achieved a PEDro score of 5, with a level of evidence 2, where adapted exercise games (i.e., active activities with a softball) significantly decreased agitated behaviors, such as searching or wandering behaviors (54%, P < .05), whereas escaping restraints had no significant change (40%, P = .07). Four articles used a cross-sectional design with a level of evidence 5, and results indicated that lighting conditions had no effect on disruptive behaviors such as door testing/exiting, and few persons with dementia who exercises in ways other than walking may influence sundown syndrome and sleep quality. Four studies used a single-case study design with a baseline phase and had a level of evidence 4, indicating that cloth barriers reduced entry into restricted areas with a high treatment acceptability, music therapy can increase the amount of time seated by the persons with dementia, and highlighted the need to educate caregivers that all persons with dementia are at risk of getting lost, regardless of whether they have exhibited the risky behavior in the past. Early education would allow caregivers to adopt preventative measures to reduce these impending risks. One study used a pretest-posttest design, with a level of evidence of 4. Results demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating a wall mural painted on the entrance of doorways, through the reduction of door testing behaviors exhibited by the participants. Two articles used qualitative methods, which cannot be assessed using Sackett's criteria [36] .

Regarding studies that included high- and low-tech solutions, one study included an RCT design [41] ; however, the details were not explained. Results from this study highlighted that most devices presently used by family caregivers do not comprise new technology but rather use established items, such as baby monitors, and home modifications that are recommended by an occupational or physical therapist. There was level 5 evidence from two case study [42] , [43] designs indicating that no evidence of benefit from exercise or walking therapies were found, that tracking devices and home alarms and sensors both effectively detected wandering and locating lost patients in uncontrolled, nonrandomized studies, and that IC tag monitoring system needed further improvement for clinical use.

- (d) Usability and strategy acceptance. Of the peer-reviewed studies, 12% (13 studies) aimed to study the usability and acceptance of wander-management strategies. Of these, nine (69%, 9/13) examined acceptance of high-tech solutions and 4 (31%, 4/13) examined acceptance of low-tech solutions. Overall acceptability and usability of these strategies were high among participants. For example, one study found that most respondents agreed that the use of locator devices was superior to existing search methods and would improve quality of life of caregivers and persons with dementia, that they were appropriate devices, and that they could operate the device successfully [24] . Those who were more inclined to use wander-management technologies were older adults who had been lost once or more (89%) or who had been diagnosed with mild dementia and had a history of being lost (73%) [44] . For low-tech solutions, cloth barriers, for example, were found to have high treatment acceptability [22] . Low-tech solutions were also seen as strategies that have already been implemented within a person's home, in part due to their affordable nature, and as established strategies that result from professional recommendations from occupational and physical therapists [41] .

- (e) Although the acceptability of certain strategies was high, others did not have the same result. Locator devices used by Yung-Ching & Leung (2012) [44] , for example, were met with resistance. Barriers toward the implementation of wander-management strategies are suggested to be partly related to caregivers' acceptance of the suggestions, which they often perceive as not necessary or that they would not work in their situation. In addition to acceptance of wander-management strategies, barriers on the use of high-tech strategies include concerns about damaging the device, cost of equipment, difficulties in using the strategy, false alarms caused by the device, uncomfortable wear of the device, inaccuracy of the coordinates for locator devices, forgetting to wear the device, and concerns about privacy and stigmatization. Device esthetics was also considered important in purchase consideration [44] . Barriers on the use of low-tech strategies include participants not being aware of the strategy (e.g., mirrors and grids on doors), not enough staff to implement the strategy (e.g., exercise programs), poor product design, unavailability or lack of cooperation, issues with building codes (i.e., locked door strategies), and the implementation of the strategy being challenging due to raised ethical concerns (i.e., doll therapy being seen as demeaning and patronizing).

Table 4

Ethical concerns associated with wander-management strategies

4. Discussion

This review examined the range and extent of all possible strategies used to manage wandering behavior in persons with dementia. We included 118 studies (of 4096) and 130 strategies from the gray literature. Overall, 183 high- and 143 low-tech strategies were included, with the majority (59.5%) of the strategies being derived from the scholarly literature. The percentage of strategies derived from scholarly and gray literature differs from that of Neubauer et al. [25] where most strategies were from the gray literature. This is in part due to the addition of low-tech solutions and studies that do not evaluate the usability or effectiveness of the wander-management strategies to the current review. Of the 296 strategies, there were 183 high- and 143 low-tech solutions. Of these, there were six different subcategories of high- and 14 different subcategories of low-tech strategies, with locating strategies, alarms and sensors, and distraction/redirection strategies were the most common. Of the 118 included studies, less than half (48.3%) evaluated the usability or effectiveness of the strategies.

Only 16% were clinically tested in home or community settings, and 25% were tested in formal care settings. In addition, all testing locations took place in urban settings. The lack of real-world evaluation raises question about the degree of effectiveness of the proposed wander-management strategies, and whether users are able and willing to adopt these solutions. In addition, rural regions were significantly underrepresented, leaving out a significant cohort, which may have presented different and necessary views by caregivers on the use and integration of these interventions in their communities [46] . An increased focus on usability testing in home-based rural and urban settings and the use of user-centered and participatory design approaches would enable real users to identify problems with existing strategy designs, which could enhance adoption and acceptance of wander-management strategies [47] .

Aside from a lack of usability testing and user-centered approaches of wander-management strategies, available solutions were difficult to find and were vastly scattered across the gray literature. Most high-tech solutions were available through an array of commercial websites selling the technology. Two websites, tech.findingyourwayontario.ca and alzstore.com , were the only websites containing strategies from multiple companies. Low-tech solutions were primarily suggested in Alzheimer's-specific websites such as through the Alzheimer Association; however, little information was provided on where or how to access these strategies. In addition, no website provided an in-depth description of all available low- and high-tech wander-management strategies. These findings help to support difficulties caregivers and persons with dementia may face when trying to choose a strategy that works best for their individual needs. A guideline available through different mediums and locations is therefore necessary to simplify this information for a population that is often time constrained due to their caregiving responsibilities [48] .

Although the mass diversity of wander-management strategies may be promising in terms of having multiple options to help serve the unique needs of persons with dementia and their caregivers, only 13% of studies (15/118) in this review included high- and low-tech strategies together. Even fewer (2%; 2/118) compared their effectiveness. This raises the question whether certain high- and low-tech strategies are more effective than others, and if various combinations of wander-management strategies are necessary to meet the unique needs of persons with dementia and their family caregivers. Some persons with dementia, for example, wander inside and outside of their homes [49] , whereas some may only wander in one of these settings. In terms of living arrangements, there are a growing number of persons with dementia who are living at home alone in the community, changing the scope of how one might care for these individuals [50] . When looking at the diverse context of those affected by dementia, income levels, perceptions of risk associated with wandering behavior, culture, and beliefs may all play key roles in the successful adoption of wander-management strategies [46] . These factors, however, have yet to be evaluated within the present literature.

In addition to examining the range and scope of high- and low-tech wander-management strategies in this review, we wanted to identify their level of product readiness, and to characterize the present evidence on the implementation of such interventions. Overall, most peer-reviewed articles described strategies in which they were prototypes that were planned in an operational setting. This signifies the positive state of wander-management strategies in that most have been tested in a relevant environment and are in the process of being deployed in operational environments. Despite the potential advantages of using high- and low-tech strategies to manage wandering, only 52% (61/118) of the studies could be evaluated using the PRL scale because many studies were only proposing the strategy. With 194 different high- and low-tech strategies being included in the scholarly literature alone, this highlights the sheer infancy of present strategies that are being used to manage wandering. Further research in this area is therefore required because of the low percentage of strategies that could be evaluated using the PRL scale.

Mixed outcomes were found for both high- and low-tech strategies, where positive outcomes were found for 52% of the included high-tech strategies and 50% for the low-tech strategies. Overall, the use of nonconstraining strategies provided promise to facilitate persons with dementia to support independence and enable them to engage in meaningful activities, such as walking and remaining engaged within their community [51] . For high-tech strategies, locating technologies, such as GPS and RFID devices, were suggested to have great potential for locating wandering persons with dementia quickly, provides increased confidence and peace of mind of caregivers, and was found to be a preferred option by users. The implementation of alarms and surveillance strategies were also promising. Issues, however, such as cost, over sensitivity, appearance, privacy, stigma, and the need to combine multiple products to meet the variable needs of users, are to be considered. For low-tech interventions, strategies such as door murals, methods of distraction, visual barriers, exercise programs, and therapies (i.e., doll and music therapy) all demonstrated reductions in wandering and exit seeking behaviors. Conflicting evidence, however, was found across all strategies, and scientific rigor was repeatedly mentioned as being poor quality [52] . This raises questions on the feasibility and effectiveness of the adoption of these strategies in formal and community-based settings. Aside from the outcomes that measured caregivers' perceptions on strategies to manage wandering, like the findings of Neubauer et al. [25] , none of the included studies addressed the needs and opinions of persons with dementia, more specifically those with mild dementia. Although addressing the concerns of family caregivers is important, the end outcome of these strategies is to ensure the safety of persons with dementia at risk of getting lost. The involvement of both caregivers and persons with dementia in the design and implementation of wander-management strategies is therefore critical to enable enhanced user satisfaction, adherence, and inevitably improved safety and quality of life of persons with dementia.

The significant variation of included outcomes, participant type, assessment tools, study duration, testing settings, and study design may have influenced the mixed outcomes of the high- and low-tech wander-management strategies. Intervention implementation, for example, ranged from 25 minutes to 1 year, with most (78%) being only applied for 3 months or less. The high variation and short study length indicates a need to determine a duration that is best suited for strategy development and evaluation. Longitudinal field studies are also required to identify the long-term impact of each wander-management strategy, and there remains a critical need for standardized outcomes to compare the effectiveness of strategies to manage wandering. Other measures based on models such as the Technology Acceptance Model [53] and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology [54] are necessary to ensure strategies are designed in a way that take into consideration factors that are essential to user adoption. The level of scientific evidence provided by clinical-oriented studies that used quantitative methods is low as the highest level per Sackett criteria [36] was 2, with most studies containing at level of evidence of 4 or less for both high and low tech included studies. Thus, there is a need for more RCT studies to increase the level of evidence of wander-management strategies for persons with dementia.

Finally, there is a gap in the literature with respect to privacy and ethics of persons affected using wander-management strategies. There has been no approach or recommendations published to address ethical issues. Future studies on privacy versus safety, the influence of stigma, and conflicts of interest between caregivers and persons with dementia need to be further explored.

4.1. Limitations of this review

We could only quantitatively assess the strength of studies that used RCTs (using PEDro scale); as far as we know there is no standardized scale that determines the quality of either quantitative or qualitative non-RCT studies. Although there are tools and guidelines available for performing a critical appraisal of research literature, the result was a proxy measure of quality. Without a scale, comparison of the relative quality of the included studies was not possible.

5. Future research and conclusions

From this review, we can conclude that many high- and low-tech strategies exist to manage the negative outcomes associated with wandering in persons with dementia. There is a general agreement that wander-management strategies can reduce risks associated with wandering, while enabling persons with dementia with a sense of freedom and independence. Further research could determine the factors that may influence intervention adoption and demonstrate the efficacy of high- and low-tech wander-management strategies.

Research in Context

- 1. Systematic review: We conducted an extensive search on gray and scholarly literature databases. Three levels of screening were employed, that is, title screening, abstract screening, and full-text screening.

- 2. Interpretation: We identified six categories of high-tech and 14 subcategories of low-tech strategies that can be used by caregivers and persons with dementia. Although wander-management strategies were believed to mitigate the risks associated with wandering, few addressed ethical issues, few were evaluated in community settings, and the overall scientific evidence from these outcomes was low. Available solutions were scattered across the gray literature and difficult to find.

- 3. Future directions: Rigorous research is required to demonstrate the efficacy of high- and low-tech wander-management strategies and their feasibility in urban and rural community-dwelling environments. A guideline is also necessary to simplify all possible strategy types and to allow stakeholders to choose wander-management strategies based on their individual needs.

Acknowledgments

The first author received support from the Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital through the Dr. Peter N. McCracken Legacy Scholarship, Thelma R. Scambler Scholarship, Gyro Club of Edmonton Graduate Scholarship, and the Alberta Association on Gerontology Edmonton Chapter Student Award.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2018.08.001 .

Supplementary data

- Best of Senior Living

- Most Friendly

- Best Meals and Dining

- Best Activities

- How Our Service Works

- Testimonials

- Leadership Team

- News & PR

Dementia and Wandering: Causes, Prevention, and Tips You Should Know

What caregivers can do about wandering

The Joint Commission International considers wandering a sentinel event , which is an event that can result in temporary, severe, or permanent harm or death. [14] The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event. Viewed Aug. 20, 2023. Found on the internet at https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/sentinel-event Maintaining a safe environment can help prevent wandering and injury.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, as the disease progresses, you can make your home safer with tactics that include making doors the same color as walls to camouflage them, installing monitoring devices above doors to detect when they’re opened, installing or planting fences or hedges around patios and yards, and creating indoor areas that are safe to explore. [4] Alzheimer’s Association. Wandering. Found on the internet at https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering

Conduct a wandering risk assessment

A wandering risk assessment evaluates a person’s condition and likelihood of wandering. Several tools can help determine an older adult’s risk of wandering, including the Rating Scale for Aggressive Behavior in the Elderly (RAGE) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), which measures dementia-related behavioral symptoms . [15] American Psychological Association. Neuropsychiatric Inventory. 2011. Foud on the internet at https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/neuropsychiatric-inventory

Consider having a risk assessment done by a health provider, so you can be fully prepared for a wandering incident while someone is in your care.

If you’re unsure if a professional assessment is needed, conducting a basic at-home assessment of your care recipient’s habits can help determine if they may be at risk for wandering behavior. Ask yourself questions, like: [6] MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management [16] Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Elopement. Dec. 1, 2007. Found on the internet at https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/elopement

- How frequently has your care recipient wandered?

- When was the first time your care recipient wandered?

- Do they tend to wander more during the day or night?

- Are common triggers noise or discomfort?

- When your care recipient wanders, is it random, or does it happen at regular intervals?

- Can you identify a motivation for when your care recipient wanders?

- Does your care recipient have a court-appointed legal guardian?

- Is your care recipient dangerous to you or others?

- Has cognitive decline impacted your care recipient’s ability to make decisions?

These questions are excellent for caregivers to be familiar with, so they’re not caught (completely) off-guard if an incident occurs. Answering these questions may provide a reliable assessment of wandering risk. Once you complete this assessment, it should assist in determining if further assessment is needed.

Check out our Wandering Risk Assessment

Unable to display PDF file.

Understand triggers

Recognizing the behaviors or events that may lead to wandering is one of the most critical factors caregivers need to prevent this from occurring. Examples of potential triggers for missing incidents include: [9] ECRI Institute. Continuing Care Risk Management: Wandering and Elopement. April 2014. Found on the internet at https://alnursing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WanderingandElopementPacket.pdf [6] MeetCaregivers. Elopement and Wandering in Seniors. June 27, 2022. Found on the internet at https://meetcaregivers.com/dementia-wandering-prevention-management