- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

John Cabot (or Giovanni Caboto, as he was known in Italy) was an Italian explorer and navigator who was among the first to think of sailing westward to reach the riches of Asia. Though the details of his life and expeditions are subject to debate, by the late 1490s he was living in England, where he gained a commission from King Henry VII to make an expedition across the Atlantic. He set sail in May 1497 and made landfall in late June, probably in modern-day Canada. After returning to England to report his success, Cabot departed on a final expedition in 1498, but was allegedly never seen again.

Giovanni Caboto was born circa 1450 in Genoa, and moved to Venice around 1461; he became a Venetian citizen in 1476. Evidence suggests that he worked as a merchant in the spice trade of the Levant, or eastern Mediterranean, and may have traveled as far as Mecca, then an important trading center for Oriental and Western goods.

He studied navigation and map-making during this period, and read the stories of Marco Polo and his adventures in the fabulous cities of Asia. Similar to his countryman Christopher Columbus , Cabot appears to have become interested in the possibility of reaching the rich gold, silk, gem and spice markets of Asia by sailing in a westward direction.

Did you know? John Cabot's landing in 1497 is generally thought to be the first European encounter with the North American continent since Leif Eriksson and the Vikings explored the area they called Vinland in the 11th century.

For the next several decades, Cabot’s exact activities are unknown; he may have been forced to leave Venice because of outstanding debts. He then spent several years in Valencia and Seville, Spain, where he worked as a maritime engineer with varying degrees of success.

Cabot may have been in Valencia in 1493, when Columbus passed through the city on his way to report to the Spanish monarchs the results of his voyage (including his mistaken belief that he had in fact reached Asia).

By late 1495, Cabot had reached Bristol, England, a port city that had served as a starting point for several previous expeditions across the North Atlantic. From there, he worked to convince the British crown that England did not have to stand aside while Spain took the lead in exploration of the New World , and that it was possible to reach Asia on a more northerly route than the one Columbus had taken.

First and Second Voyages

In 1496, King Henry VII issued letters patent to Cabot and his son, which authorized them to make a voyage of discovery and to return with goods for sale on the English market. After a first, aborted attempt in 1496, Cabot sailed out of Bristol on the small ship Matthew in May 1497, with a crew of about 18 men.

Cabot’s most successful expedition made landfall in North America on June 24; the exact location is disputed, but may have been southern Labrador, the island of Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island. Reports about their exploration vary, but when Cabot and his men went ashore, he reportedly saw signs of habitation but few if any people. He took possession of the land for King Henry, but hoisted both the English and Venetian flags.

Grand Banks

Cabot explored the area and named various features of the region, including Cape Discovery, Island of St. John, St. George’s Cape, Trinity Islands and England’s Cape. These may correspond to modern-day places located around what became known as Cabot Strait, the 60-mile-wide channel running between southwestern Newfoundland and northern Cape Breton Island.

Like Columbus, Cabot believed that he had reached Asia’s northeast coast. He returned to Bristol in August 1497 with extremely favorable reports of the exploration. Among his discoveries was the rich fishing grounds of the Grand Banks off the coast of Canada, where his crew was allegedly able to fill baskets with cod by simply dropping the baskets into the water.

John Cabot’s Final Voyage

In London in late 1497, Cabot proposed to King Henry VII that he set out on another expedition across the north Atlantic. This time, he would continue westward from his first landfall until he reached the island of Cipangu ( Japan ). In February 1498, the king issued letters patent for the second voyage, and that May Cabot set off once again from Bristol, but this time with five ships and about 300 men.

The exact fate of the expedition has not been established, but by July one of the ships had been damaged and sought anchorage in Ireland. Reportedly the other four ships continued westward. It was believed that the ships had been caught in a severe storm, and by 1499, Cabot himself was presumed to have perished at sea.

Some evidence, however, suggests that Cabot and some members of his crew may have stayed in the New World; other documents suggest that he and his crew returned to England at some point. A Spanish map from 1500 includes the northern coast of North America with English place names and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.”

What Did John Cabot Discover?

In addition to laying the groundwork for British land claims in Canada, his expeditions proved the existence of a shorter route across the northern Atlantic Ocean, which would later facilitate the establishment of other British colonies in North America .

One of John Cabot's sons, Sebastian, was also an explorer who sailed under the flags of England and Spain.

John Cabot. Royal Museums Greenwich . Who Was John Cabot? John Cabot University . John Cabot. The Canadian Encyclopedia .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 10 May 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 10 May 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Hunter, D. (2017). John Cabot. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed May 10, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed May 10, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Article by Douglas Hunter

Published Online January 7, 2008

Last Edited May 19, 2017

Early Years in Venice

John Cabot had a complex and shadowy early life. He was probably born before 1450 in Italy and was awarded Venetian citizenship in 1476, which meant he had been living there for at least fifteen years. People often signed their names in different ways at this time, and Cabot was no exception. In one 1476 document he identified himself as Zuan Chabotto, which gives a clue to his origins. It combined Zuan, the Venetian form for Giovanni, with a family name that suggested an origin somewhere on the Italian peninsula, since a Venetian would have spelled it Caboto. He had a Venetian wife, Mattea, and three sons, one of whom, Sebastian, rose to the rank of pilot-major of Spain for the Indies trade. Cabot was a merchant; Venetian records identify him as a hide trader, and in 1483 he sold a female slave in Crete. He was also a property developer in Venice and nearby Chioggia.

Cabot in Spain

In 1488, Cabot fled Venice with his family because he owed prominent people money. Where the Cabot family initially went is unknown, but by 1490 John Cabot was in Valencia, Spain, which like Venice was a city of canals. In 1492, he partnered with a Basque merchant named Gaspar Rull in a proposal to build an artificial harbour for Valencia on its Mediterranean coast. In April 1492, the project captured the enthusiasm of Fernando (Ferdinand), king of Aragon and husband of Isabel, queen of Castille, who together ruled what is now a unified Spain. The royal couple had just agreed to send Christopher Columbus on his now-famous voyage to the Americas. In the autumn of 1492, Fernando encouraged the governor-general of Valencia to find a way to finance Cabot’s harbour scheme. However, in March 1493, the council of Valencia decided it could not fund Cabot’s plan. Despite Fernando’s attempt to move the project forward that April, the scheme collapsed.

Cabot disappeared from the historical record until June 1494, when he resurfaced in another marine engineering plan dear to the Spanish monarchs. He was hired to build a fixed bridge link in Seville to its maritime centre, the island of Triana in the Guadalquivir River, which otherwise was serviced by a troublesome floating one. Though Columbus had reached the Americas, he believed he had found land on the eastern edge of Asia, and Seville had been chosen as the headquarters of what Spain imagined was a lucrative transatlantic trade route. Cabot’s assignment thus was an important one, but something went wrong. In December 1494, a group of leading citizens of Seville gathered, unhappy with Cabot’s lack of progress, given the funds he had been provided. At least one of them thought he should be banished from the city. By then, Cabot probably had left town.

Cabot in England

Following the demise of Cabot’s Seville bridge project, the marine engineer again disappeared from the historical record. In March 1496 he resurfaced, this time as the commander of a proposed westward voyage under the flag of the King of England, Henry VII. Although there is no documentary proof, during Cabot’s absence from the historical record, between April 1493 and June 1494, he could have sailed with Columbus’s second voyage to the Caribbean. Most of the names of the over 1,000 people who accompanied Columbus weren’t recorded; however, Cabot could have been among the marine engineers on the voyage’s 17 ships who were expected to construct a harbour facility in what is now Haiti. Had Cabot been present on this journey, Henry VII would have had some basis to believe the would-be Venetian explorer could make a similar voyage to the far side of the Atlantic. It would help explain why Henry VII hired Cabot, a foreigner with a problematic résumé and no known nautical expertise, to make such a journey.

On 5 March 1496, Henry awarded Cabot and his three sons a generous letters patent, a document granting them the right to explore and exploit areas unknown to Christian monarchs. The Cabots were authorized to sail to “all parts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns,” with as many as five ships, manned and equipped at their own expense. The Cabots were to “find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.” The Cabots would serve as Henry’s “vassals, and governors lieutenants and deputies” in whatever lands met the criteria of the patent, and they were given the right to “conquer, occupy and possess whatsoever towns, castles, cities and islands by them discovered.” With the letters patent, the Cabots could secure financial backing. Two payments were made in April and May 1496 to John Cabot by the House of Bardi (a family of Florentine merchants) to fund his search for “the new land,” suggesting his investors thought he was looking for more than a northern trade route to Asia.

First Voyage (1496)

Cabot’s first voyage departed Bristol, England, in 1496. Sailing westward in the north Atlantic was no easy task. The prevailing weather patterns track from west to east, and ships of Cabot’s time could scarcely sail toward the wind. No first-hand accounts of Cabot’s first attempt to sail west survive. Historians only know that it was a failure, with Cabot apparently rebuffed by stormy weather.

Second Voyage (1497)

Cabot mounted a second attempt from Bristol in May 1497, using a ship called the Matthew . It may have been a happy coincidence that its name was the English version of Cabot’s wife’s name, Mattea. There are no records of the ship’s individual crewmembers, and all the accounts of the voyage are second-hand — a remarkable lack of documentation for a voyage that would be the foundation of England’s claim to North America.

Historians have long debated exactly where Cabot explored. The most authoritative report of his journey was a letter by a London merchant named Hugh Say. Written in the winter of 1497-98, but only discovered in Spanish archives in the mid-1950s, Say’s letter (written in Spanish) was addressed to a “great admiral” in Spain who may have been Columbus.

The rough latitudes Say provided suggest Cabot made landfall around southern Labrador and northernmost Newfoundland , then worked his way southeast along the coast until he reached the Avalon Peninsula , at which point he began the journey home. Cabot led a fearful crew, with reports suggesting they never ventured more than a crossbow’s shot into the land. They saw two running figures in the woods that might have been human or animal and brought back an unstrung bow “painted with brazil,” suggesting it was decorated with red ochre by the Beothuk of Newfoundland or the Innu of Labrador. He also brought back a snare for capturing game and a needle for making nets. Cabot thought (wrongly) there might be tilled lands, written in Say’s letter as tierras labradas , which may have been the source of the name for Labrador. Say also said it was certain the land Cabot coasted was Brasil, a fabled island thought to exist somewhere west of Ireland.

Others who heard about Cabot’s voyage suggested he saw two islands, a misconception possibly resulting from the deep indentations of Newfoundland’s Conception and Trinity Bays, and arrived at the coast of East Asia. Some believed he had reached another fabled island, the Isle of Seven Cities, thought to exist in the Atlantic.

There were also reports Cabot had found an enormous new fishery. In December 1497, the Milanese ambassador to England reported hearing Cabot assert the sea was “swarming with fish, which can be taken not only with the net, but in baskets let down with a stone.” The fish of course were cod , and their abundance on the Grand Banks later laid the foundation for Newfoundland’s fishing industry.

Third Voyage (1498)

Henry VII rewarded Cabot with a royal pension on December 1497 and a renewed letters patent in February 1498 that gave him additional rights to help mount the next voyage. The additional rights included the ability to charter up to six ships as large as 200 tons. The voyage was again supposed to be mounted at Cabot’s expense, although the king personally invested in one participating ship. Despite reports from the 1497 voyage of masses of fish, no preparations were made to harvest them.

A flotilla of probably five ships sailed in early May. What became of it remains a mystery. Historians long presumed, based on a flawed account by the chronicler Polydore Vergil, that all the ships were lost, but at least one must have returned. A map made by Spanish cartographer Juan de la Cosa in 1500 — one of the earliest European maps to incorporate the Americas — included details of the coastline with English place names, flags and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.” The map suggests Cabot’s voyage ventured perhaps as far south as modern New England and Long Island.

Cabot’s royal pension did continue to be paid until 1499, but if he was lost on the 1498 voyage, it may only have been collected in his absence by one of his sons, or his widow, Mattea.

Despite being so poorly documented, Cabot’s 1497 voyage became the basis of English claims to North America. At the time, the westward voyages of exploration out of Bristol between 1496 and about 1506, as well as one by Sebastian Cabot around 1508, were probably considered failures. Their purpose was to secure trade opportunities with Asia, not new fishing grounds, which not even Cabot was interested in, despite praising the teeming schools. Instead of trade with Asia, Cabot and his Bristol successors found an enormous land mass blocking the way and no obvious source of wealth.

- Newfoundland and Labrador

Further Reading

Douglas Hunter, The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot and a Lost History of Discovery (2012).

External Links

Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador A biography of John Cabot from this site sponsored by Memorial University.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography An account of John Cabot’s life from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Recommended

Giovanni da verrazzano, jacques cartier.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert: Elizabethan Explorer

Explorer John Cabot made a British claim to land in Canada, mistaking it for Asia, during his 1497 voyage on the ship Matthew.

(1450-1500)

Who Was John Cabot?

John Cabot was a Venetian explorer and navigator known for his 1497 voyage to North America, where he claimed land in Canada for England. After setting sail in May 1498 for a return voyage to North America, he disappeared and Cabot's final days remain a mystery.

Cabot was born Giovanni Caboto around 1450 in Genoa, Italy. Cabot was the son of a spice merchant, Giulio Caboto. At age 11, the family moved from Genoa to Venice, where Cabot learned sailing and navigation from Italian seamen and merchants.

Discoveries

In 1497, Cabot traveled by sea from Bristol to Canada, which he mistook for Asia. Cabot made a claim to the North American land for King Henry VII of England , setting the course for England's rise to power in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Cabot’s Route

Like Columbus, Cabot believed that sailing west from Europe was the shorter route to Asia. Hearing of opportunities in England, Cabot traveled there and met with King Henry VII, who gave him a grant to "seeke out, discover, and finde" new lands for England. In early May of 1497, Cabot left Bristol, England, on the Matthew , a fast and able ship weighing 50 tons, with a crew of 18 men. Cabot and his crew sailed west and north, under Cabot's belief that the route to Asia would be shorter from northern Europe than Columbus's voyage along the trade winds. On June 24, 1497, 50 days into the voyage, Cabot landed on the east coast of North America.

The precise location of Cabot’s landing is subject to controversy. Some historians believe that Cabot landed at Cape Breton Island or mainland Nova Scotia. Others believe he may have landed at Newfoundland, Labrador or even Maine. Though the Matthew 's logs are incomplete, it is believed that Cabot went ashore with a small party and claimed the land for the King of England.

In July 1497, the ship sailed for England and arrived in Bristol on August 6, 1497. Cabot was soon rewarded with a pension of £20 and the gratitude of King Henry VII.

Wife and Kids

In 1474, Cabot married a young woman named Mattea. The couple had three sons: Ludovico, Sancto and Sebastiano. Sebastiano would later follow in his father’s footsteps, becoming an explorer in his own right.

Death and Legacy

It is believed Cabot died sometime in 1499 or 1500, but his fate remains a mystery. In February 1498, Cabot was given permission to make a new voyage to North America; in May of that year, he departed from Bristol, England, with five ships and a crew of 300 men. The ships carried ample provisions and small samplings of cloth, lace points and other "trifles," suggesting an expectation of fostering trade with Indigenous peoples. En route, one ship became disabled and sailed to Ireland, while the other four ships continued on. From this point, there is only speculation as to the fate of the voyage and Cabot.

For many years, it was believed that the ships were lost at sea. More recently, however, documents have emerged that place Cabot in England in 1500, laying speculation that he and his crew actually survived the voyage. Historians have also found evidence to suggest that Cabot's expedition explored the eastern Canadian coast, and that a priest accompanying the expedition might have established a Christian settlement in Newfoundland.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: John Cabot

- Birth Year: 1450

- Birth City: Genoa

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Explorer John Cabot made a British claim to land in Canada, mistaking it for Asia, during his 1497 voyage on the ship Matthew.

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- John Cabot was inspired by the discoveries of Bartolomeu Dias and Christopher Columbus.

- Cabot's youngest son also became an explorer in his own right

- Death Year: 1500

- Sayled in this tracte so farre towarde the weste, that the Ilande of Cuba bee on my lefte hande, in manere in the same degree of longitude.

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

Find out how Cabot helped kick-start England's transatlantic voyages of discovery

Italian explorer, John Cabot, is famed for discovering Newfoundland and was instrumental in the development of the transatlantic trade between England and the Americas.

Although not born in England, John Cabot led English ships on voyages of discovery in Tudor times. John Cabot (about 1450–98) was an experienced Italian seafarer who came to live in England during the reign of Henry VII. In 1497 he sailed west from Bristol hoping to find a shorter route to Asia, a land believed to be rich in gold, spices and other luxuries. After a month, he discovered a 'new found land', today known as Newfoundland in Canada. Cabot is credited for claiming North America for England and kick-starting a century of English transatlantic exploration.

Why did Cabot come to England?

Born in Genoa around 1450, Cabot's Italian name was Giovanni Caboto. He had read of fabulous Chinese cities in the writings of Marco Polo and wanted to see them for himself. He hoped to reach them by sailing west, across the Atlantic.

Like Christopher Columbus, Cabot found it very difficult to convince backers to pay for the ships he needed to test out his ideas about the world. After failing to persuade the royal courts of Europe, he arrived with his family in 1484, to try to persuade merchants in London and Bristol to pay for his planned voyage. Before he set off, Cabot heard that Columbus had sailed west across the Atlantic and reached land. At the time, everyone believed that this land was the Indies, or Spice Islands.

Why did King Henry VII agree to help to pay for Cabot's expedition?

If Cabot’s predictions about the new route were right, he wouldn’t be the only one to profit. King Henry VII would also take his share. Everybody believed that Cathay and Cipangu (China and Japan) were rich in gold, gems, spices and silks. If Asia had been where Cabot thought it was, it would have made England the greatest trading centre in the world for goods from the east.

What did Cabot find on his voyage?

John Cabot's ship, the Matthew , sailed from Bristol with a crew of 18 in 1497. After a month at sea, he landed and took the area in the name of King Henry VII. Cabot had reached one of the northern capes of Newfoundland. His sailors were able to catch huge numbers of cod simply by dipping baskets into the water. Cabot was rewarded with the sum of £10 by the king, for discovering a new island off the coast of China! The king would’ve been far more generous if Cabot had brought home spices.

What happened to Cabot?

In 1498, Cabot was given permission by Henry VII to take ships on a new expedition to continue west from Newfoundland. The aim was to discover Japan. Cabot set out from Bristol with 300 men in May 1498. The five ships carried supplies for a year's travelling. There is no further record of Cabot and his crews, though there is now some evidence he may have returned and died in England. His son, Sebastian (1474–1577), followed in his footsteps, exploring various parts of the world for England and Spain.

View a replica of John Cabot's ship, which is open to the public in Bristol

Gifts inspired by seafaring in the Tudor and Stuart eras

Learn more about the emergence of a maritime nation

The UK National Charity for History

Password Sign In

Become a Member | Register for free

The Voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot

Classic Pamphlet

- Add to My HA Add to folder Default Folder [New Folder] Add

Discovering North America

Historians have debated the voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot who first discovered North America under the reign of Henry VII. The primary question was who [John or Sebastian] was responsible for the successful discovery . A 1516 account stated Sebastian Cabot sailed from Bristol to Cathay, in the service of Henry VII; environmental hardships had compelled Sebastian to travel to lower latitudes that led to the subsequent discovery of eastern North America. Still, early writers did not provide sufficient details of the expedition creating a number of discrepancies that undermine its validity.

In 1582, Richard Hakluyt printed letters that were granted on March 5, 1496 on behalf of King Henry VII to John Cabot that asked him to discover unknown lands in an effort to annex them for the Crown and monopolize English trade. This account, in contrast, indicated that John Cabot actually led the journey with his son Sebastian as his subordinate. Despite these opposing sources, it was not until the 19th century that historians began rejecting Sebastian as the primary discoverer of North America largely due to Richard Biddle who had published a Memoir of Sebastian Cabot in 1831. This memoir collated the sixteenth century writers with documents asserting Sebastian’s father, John Cabot, was merely a sleeping partner and an elderly merchant who did not go to sea—rendering Sebastian as the leader of the journey. Eventually, important documents emerged from unexamined archives of European states that almost irrefutably debunked Sebastian as the captain...

This resource is FREE for Student HA Members .

Non HA Members can get instant access for £3.49

Add to Basket Join the HA

Department of History

Cabot and bristol's age of discovery.

Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol's Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol, 23 Nov 2016), ISBN 0995619301, 104 pp., 71 illustrations, £11.99 rrp.

Also available as a free ebook from archive.org and the Bristol Record Society . Please note that in the digitised version of the book some images have had to be removed for copyright reasons. Many of the documents referenced in the text can be found in the document transcriptions section of the Cabot Project publications page.

Description

John Cabot's voyage to North America in 1497, on the Matthew of Bristol, has long been famous. But who was Cabot? Why did he come to Bristol? And what did he achieve? In this book, the two leading historians of the Bristol discovery voyages draw on their recent research and new discoveries to tell the story of the voyages of exploration launched from Bristol at this time. The Venetian Zuan Chabotto (John Cabot), lies at the heart of this story. But his three expeditions are set in the context of the discovery enterprises funded and led by Bristol's merchants over many decades. The book is written for the general reader and is richly illustrated to bring the fruits of the University of Bristol's acclaimed Cabot Project to the wider public.

Sample Chapters

Contents page, Introduction and Chapter 4: Cabot book sample (PDF, 1,715kB)

About the Authors

Dr Evan T. Jones is a senior lecturer in economic and social history at the University of Bristol, where he specializes in the maritime history of Bristol in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. He has published on a variety of topics including: trade, shipping, fishing and smuggling. He has been working on the port's discovery voyages since 2002. This interest gradually developed into a major international project, involving colleagues in England, Italy, Canada, the USA and Australia.

Margaret M. Condon is the chief researcher on the Cabot Project. The author of several important articles on the reign of Henry VII, she has long expertise in late medieval administrative history. Now based at the University of Winchester, she has worked with Dr Jones intensively since 2009. Jones and Condon are currently writing a major academic monograph on the Bristol Discovery Voyages, to provide the full account of their research and findings to date.

Availability

The book can be bought direct from the University of Bristol online shop both for UK Delivery and Overseas Delivery . It can also be purchased online from The National Archives Bookshop and can be found in a variety of outlets in Bristol, including the Matthew of Bristol , Bristol Archives and the shops of MShed , Bristol Cathedral and St Mary Redcliffe .

Those wishing to purchase copies for onwards sale, or for educational institutions, should contact Dr Evan Jones direct. Heavy discounts are available for multiple purchases, or for schools, universities and public libraries. This book was directly published by the University of Bristol as part of its commitment to Public Engagement . Any profits will be used to fund the research and associated educational activities of the Cabot Project, the authors taking no royalties from the sales. The University account for the book is 'Cabot Project Publications'.

Also available as a free ebook from archive.org and the Bristol Record Society .

John Cabot’s Voyage of 1497

Founding of newfoundland and cape breton.

There is very little precise contemporary information about the 1497 voyage. If Cabot kept a log, or made maps of his journey, they have disappeared. What we have as evidence is scanty: a few maps from the first part of the 16th century which appear to contain information obtained from Cabot, and some letters from non-participants reporting second-hand on what had occurred. As a result, there are many conflicting theories and opinions about what actually happened.

Cabot’s ship was named the Matthew , almost certainly after his wife Mattea. It was a navicula , meaning a relatively small vessel, of 50 toneles – able to carry 50 tons of wine or other cargo. It was decked, with a high sterncastle and three masts. The two forward masts carried square mainsails to propel the vessel forward. The rear mast was rigged with a lateen sail running in the same direction as the keel, which helped the vessel sail into the wind.

There were about 20 people on board. Cabot, a Genoese barber(surgeon), a Burgundian, two Bristol merchants, and Bristol sailors. Whether any of Cabot’s sons were members of the crew cannot be verified.

The Matthew left Bristol sometime in May, 1497. Some scholars think it was early in the month, others towards the end. It is generally agreed that he would have sailed down the Bristol Channel, across to Ireland, and then north along the west coast of Ireland before turning out to sea.

But how far north did he go? Again, it is impossible to be certain. All one can say is that Cabot’s point of departure was somewhere between 51 and 54 degrees north latitude, with most modern scholars favouring a northerly location.

The next point of debate is how far Cabot might have drifted to the south during his crossing. Some scholars have argued that ocean currents and magnetic variations affecting his compass could have pulled Cabot far off course. Others think that Cabot could have held approximately to his latitude. In any event, some 35 days after leaving Bristol he sighted land, probably on 24 June. Where was the landfall?

Cabot was back in Bristol on 6 August, after a 15 day return crossing. This means that he explored the region for about a month.

Newfoundland Joining Canada

Newfoundland resisted joining Canada and was an independent dominion in the early 20th century. Fishing was always the dominant industry, but the economy collapsed in the Great Depression of the 1930s and the people voluntarily relinquished their independence to become a British colony again. Prosperity and self-confidence returned during the Second World War, and after intense debate the people voted to join Canada in 1949.

The “golden era” came in the early 20th century however the sudden collapse of the cod fishing industry was a terrific blow in the 1990s. The historic cultural and political tensions between British Protestants and Irish Catholics faded, and a new spirit of a unified Newfoundland identity has recently emerged through songs and popular culture.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This is a demo store for testing purposes — no orders shall be fulfilled. Dismiss

- Inventors and Inventions

- Philosophers

- Film, TV, Theatre - Actors and Originators

- Playwrights

- Advertising

- Military History

- Politicians

- Publications

- Visual Arts

John Cabot - North American Trail-blazer

Contribution to British Heritage.

Legacy and Success

General information.

- John Cabot en.wikipedia.org

You might also like

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with EHR?

- About The English Historical Review

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Books for Review

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- Appendix II

- < Previous

The Matthew of Bristol and the Financiers of John Cabot's 1497 Voyage to North America *

For their comments on earlier versions of this article, I would like to thank Gwen Seabourne, James Lee, Peter Pope, Sarah Rose and Wendy Childs.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Evan Jones, The Matthew of Bristol and the Financiers of John Cabot's 1497 Voyage to North America, The English Historical Review , Volume CXXI, Issue 492, June 2006, Pages 778–795, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cel106

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Matthew of Bristol is the vessel in which the Genoese explorer, John Cabot, sailed with his Bristol companions on their 1497 voyage of discovery to North America. Yet, despite the fame of the voyage and the ship, little has been known about the Matthew , or about Cabot's relationship with his English backers. This has encouraged the proliferation of mythic representations of the voyage, in which the iconic Matthew is cast as a specially built discovery vessel and Cabot is portrayed as an intrepid and essentially independent explorer – a man worthy to stand alongside Columbus as a ‘proto-American’ pioneer.

This article challenges such representations of the voyage in two ways. First, it reconstructs the history of the ship to 1511 and sets her within the context of the Bristol marine. It is shown that the Matthew was a thoroughly unremarkable product of the Bristol shipping industry, which was simply chartered out of the town's marine for the 1497 expedition. Following this, the Matthew returned to ordinary commercial duties, serving the port's trade with Biscay and southeast Ireland. Second, the article explores Cabot's probable relationship with his financiers. The aim is to demonstrate how far he was from being the independent pioneer of myth. It is suggested, instead, that his backers may have regarded him as little more than hired talent, a skilled navigator whom they employed to help them fulfil their own ambitions. It is also shown that Cabot's relationship with his financiers and their port was such that, had his voyage been a commercial success, Bristol would have gained far more from such success than John Cabot or his heirs.

The article is accompanied by previously unpublished transcriptions from two documents, which throw valuable light on the history of the Matthew .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4534

- Print ISSN 0013-8266

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- By Time Period

- By Location

- Mission Statement

- Books and Documents

- Ask a NL Question

- How to Cite NL Heritage Website

- ____________

- Archival Mysteries

- Alien Enemies, 1914-1918

- Icefields Disaster

- Colony of Avalon

- Let's Teach About Women

- Silk Robes and Sou'westers

- First World War

- Première Guerre mondiale

- DNE Word Form Database

- Dialect Atlas of NL

- Partners List from Old Site

- Introduction

- Bibliography

- Works Cited

- Abbreviations

- First Edition Corrections

- Second Edition Preface

- Bibliography (supplement)

- Works Cited (supplement)

- Abbreviations (supplement)

- Documentary Video Series (English)

- Une série de documentaires (en français)

- Arts Videos

- Archival Videos

- Table of Contents

- En français

- Exploration and Settlement

- Government and Politics

- Indigenous Peoples

- Natural Environment

- Society and Culture

- Archives and Special Collections

- Ferryland and the Colony of Avalon

- Government House

- Mount Pearl Junior High School

- Registered Heritage Structures

- Stephenville Integrated High School Project

- Women's History Group Walking Tour

John Cabot's Voyage of 1497

There is very little precise contemporary information about the 1497 voyage. If Cabot kept a log, or made maps of his journey, they have disappeared. What we have as evidence is scanty: a few maps from the first part of the 16th century which appear to contain information obtained from Cabot, and some letters from non-participants reporting second-hand on what had occurred. As a result, there are many conflicting theories and opinions about what actually happened.

Cabot's ship was named the Matthew , almost certainly after his wife Mattea. It was a navicula , meaning a relatively small vessel, of 50 toneles - able to carry 50 tons of wine or other cargo. It was decked, with a high sterncastle and three masts. The two forward masts carried square mainsails to propel the vessel forward. The rear mast was rigged with a lateen sail running in the same direction as the keel, which helped the vessel sail into the wind.

There were about 20 people on board. Cabot, a Genoese barber(surgeon), a Burgundian, two Bristol merchants, and Bristol sailors. Whether any of Cabot's sons were members of the crew cannot be verified.

The Matthew left Bristol sometime in May, 1497. Some scholars think it was early in the month, others towards the end. It is generally agreed that he would have sailed down the Bristol Channel, across to Ireland, and then north along the west coast of Ireland before turning out to sea.

But how far north did he go? Again, it is impossible to be certain. All one can say is that Cabot's point of departure was somewhere between 51 and 54 degrees north latitude, with most modern scholars favouring a northerly location.

The next point of debate is how far Cabot might have drifted to the south during his crossing. Some scholars have argued that ocean currents and magnetic variations affecting his compass could have pulled Cabot far off course. Others think that Cabot could have held approximately to his latitude. In any event, some 35 days after leaving Bristol he sighted land, probably on 24 June. Where was the landfall?

Cabot was back in Bristol on 6 August, after a 15 day return crossing. This means that he explored the region for about a month. Where did he go?

Version française

Related Subjects

Share and print this article:.

Contact | © Copyright 1997 – 2024 Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site, unless otherwise stated.

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The voyages of the Cabots and the English discovery of North America under Henry VII and Henry VIII

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

1,636 Views

5 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by [email protected] on February 13, 2012

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Search Omniatlas

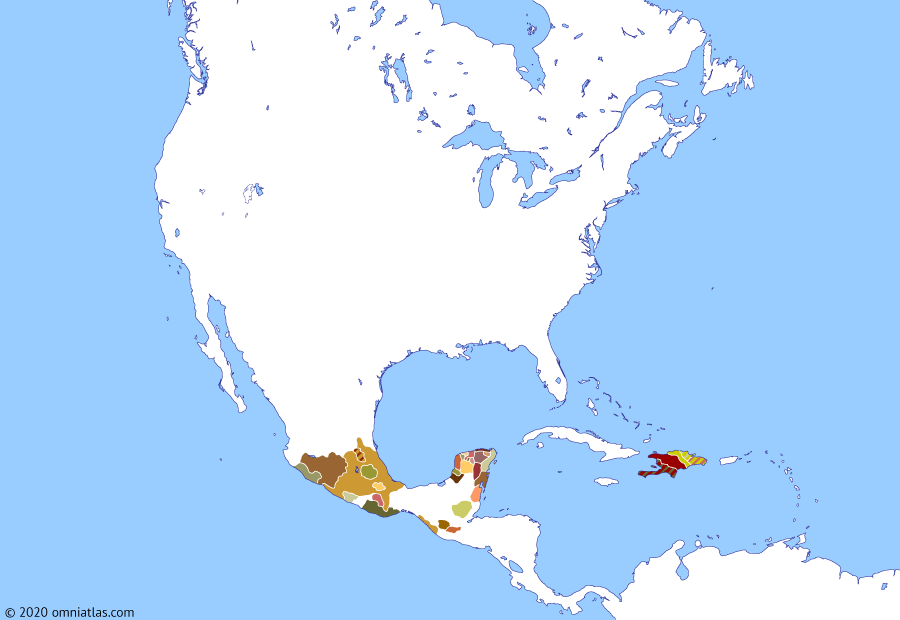

Navigate between maps, north america 1497: john cabot’s expeditions.

?? 1497–Aug 1499 Roldán in revolt against Columbus

May–Aug 1497 John Cabot explores coast of Newfoundland

24 June 1497

Age of columbus, north america, john cabot’s expeditions.

Columbus’ discoveries created excitement in Europe and in 1496 Henry VII of England agreed to sponsor another Italian navigator, John Cabot , in his own explorations. Cabot arrived off the coast of Newfoundland in 1497, possibly—his voyages are poorly documented—returning to explore the coast of North America the following year, but, like Columbus, was disappointed to find no wealthy Asian kingdoms. Meanwhile, Columbus faced renewed problems in Hispaniola when Roldán led a revolt of Spanish settlers and Taíno against his authority (1497–99) .

Main Events

1497–31 aug 1499 roldán’s rebellion ▲.

In 1496 Christopher Columbus left Hispaniola for Spain, leaving his brother Bartholomew in charge of the colony. Dissatisfied with the governance of the Columbus brothers, Francisco Roldán, the mayor of La Isabela, seized this opportunity to lead many of the Spanish settlers and soldiers in revolt in 1497. Basing himself in the semi-independent Taíno chiefdom of Jaragua, Roldán’s actions also encouraged the short-lived revolt of the chiefdoms of Maguá and Higüey the following year. In 1498 Columbus returned, finally bringing an end to the revolt by buying Roldán off with concessions. in wikipedia

? May–6 Aug 1497 John Cabot’s second voyage ▲

In March 1496 the Venetian navigator Giovanni Caboto—John Cabot in English—was granted letters patent by Henry VII of England to explore the seas. After an unsuccessful first voyage, Cabot departed Bristol aboard the Matthew in May 1497, sighting part of North America—most likely Cape Breton Island or one of Newfoundland’s capes—on 24 June. Landing just once to take possession of the land for the king, Cabot proceeded northwards along the coast before returning to arrive back in England in August. in wikipedia

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- . "John Cabot". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . development.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 10 May 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . development.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 10 May 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- (2017). John Cabot. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://development.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://development.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- . "John Cabot." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by , Accessed May 10, 2024, https://development.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by , Accessed May 10, 2024, https://development.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Published Online January 7, 2008

Last Edited May 19, 2017

Early Years in Venice

John Cabot had a complex and shadowy early life. He was probably born before 1450 in Italy and was awarded Venetian citizenship in 1476, which meant he had been living there for at least fifteen years. People often signed their names in different ways at this time, and Cabot was no exception. In one 1476 document he identified himself as Zuan Chabotto, which gives a clue to his origins. It combined Zuan, the Venetian form for Giovanni, with a family name that suggested an origin somewhere on the Italian peninsula, since a Venetian would have spelled it Caboto. He had a Venetian wife, Mattea, and three sons, one of whom, Sebastian, rose to the rank of pilot-major of Spain for the Indies trade. Cabot was a merchant; Venetian records identify him as a hide trader, and in 1483 he sold a female slave in Crete. He was also a property developer in Venice and nearby Chioggia.

Cabot in Spain

In 1488, Cabot fled Venice with his family because he owed prominent people money. Where the Cabot family initially went is unknown, but by 1490 John Cabot was in Valencia, Spain, which like Venice was a city of canals. In 1492, he partnered with a Basque merchant named Gaspar Rull in a proposal to build an artificial harbour for Valencia on its Mediterranean coast. In April 1492, the project captured the enthusiasm of Fernando (Ferdinand), king of Aragon and husband of Isabel, queen of Castille, who together ruled what is now a unified Spain. The royal couple had just agreed to send Christopher Columbus on his now-famous voyage to the Americas. In the autumn of 1492, Fernando encouraged the governor-general of Valencia to find a way to finance Cabot’s harbour scheme. However, in March 1493, the council of Valencia decided it could not fund Cabot’s plan. Despite Fernando’s attempt to move the project forward that April, the scheme collapsed.

Cabot disappeared from the historical record until June 1494, when he resurfaced in another marine engineering plan dear to the Spanish monarchs. He was hired to build a fixed bridge link in Seville to its maritime centre, the island of Triana in the Guadalquivir River, which otherwise was serviced by a troublesome floating one. Though Columbus had reached the Americas, he believed he had found land on the eastern edge of Asia, and Seville had been chosen as the headquarters of what Spain imagined was a lucrative transatlantic trade route. Cabot’s assignment thus was an important one, but something went wrong. In December 1494, a group of leading citizens of Seville gathered, unhappy with Cabot’s lack of progress, given the funds he had been provided. At least one of them thought he should be banished from the city. By then, Cabot probably had left town.

Cabot in England

Following the demise of Cabot’s Seville bridge project, the marine engineer again disappeared from the historical record. In March 1496 he resurfaced, this time as the commander of a proposed westward voyage under the flag of the King of England, Henry VII. Although there is no documentary proof, during Cabot’s absence from the historical record, between April 1493 and June 1494, he could have sailed with Columbus’s second voyage to the Caribbean. Most of the names of the over 1,000 people who accompanied Columbus weren’t recorded; however, Cabot could have been among the marine engineers on the voyage’s 17 ships who were expected to construct a harbour facility in what is now Haiti. Had Cabot been present on this journey, Henry VII would have had some basis to believe the would-be Venetian explorer could make a similar voyage to the far side of the Atlantic. It would help explain why Henry VII hired Cabot, a foreigner with a problematic résumé and no known nautical expertise, to make such a journey.

On 5 March 1496, Henry awarded Cabot and his three sons a generous letters patent, a document granting them the right to explore and exploit areas unknown to Christian monarchs. The Cabots were authorized to sail to “all parts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns,” with as many as five ships, manned and equipped at their own expense. The Cabots were to “find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.” The Cabots would serve as Henry’s “vassals, and governors lieutenants and deputies” in whatever lands met the criteria of the patent, and they were given the right to “conquer, occupy and possess whatsoever towns, castles, cities and islands by them discovered.” With the letters patent, the Cabots could secure financial backing. Two payments were made in April and May 1496 to John Cabot by the House of Bardi (a family of Florentine merchants) to fund his search for “the new land,” suggesting his investors thought he was looking for more than a northern trade route to Asia.

First Voyage (1496)

Cabot’s first voyage departed Bristol, England, in 1496. Sailing westward in the north Atlantic was no easy task. The prevailing weather patterns track from west to east, and ships of Cabot’s time could scarcely sail toward the wind. No first-hand accounts of Cabot’s first attempt to sail west survive. Historians only know that it was a failure, with Cabot apparently rebuffed by stormy weather.

Second Voyage (1497)

Cabot mounted a second attempt from Bristol in May 1497, using a ship called the Matthew . It may have been a happy coincidence that its name was the English version of Cabot’s wife’s name, Mattea. There are no records of the ship’s individual crewmembers, and all the accounts of the voyage are second-hand — a remarkable lack of documentation for a voyage that would be the foundation of England’s claim to North America.

Historians have long debated exactly where Cabot explored. The most authoritative report of his journey was a letter by a London merchant named Hugh Say. Written in the winter of 1497-98, but only discovered in Spanish archives in the mid-1950s, Say’s letter (written in Spanish) was addressed to a “great admiral” in Spain who may have been Columbus.

The rough latitudes Say provided suggest Cabot made landfall around southern Labrador and northernmost Newfoundland , then worked his way southeast along the coast until he reached the Avalon Peninsula , at which point he began the journey home. Cabot led a fearful crew, with reports suggesting they never ventured more than a crossbow’s shot into the land. They saw two running figures in the woods that might have been human or animal and brought back an unstrung bow “painted with brazil,” suggesting it was decorated with red ochre by the Beothuk of Newfoundland or the Innu of Labrador. He also brought back a snare for capturing game and a needle for making nets. Cabot thought (wrongly) there might be tilled lands, written in Say’s letter as tierras labradas , which may have been the source of the name for Labrador. Say also said it was certain the land Cabot coasted was Brasil, a fabled island thought to exist somewhere west of Ireland.

Others who heard about Cabot’s voyage suggested he saw two islands, a misconception possibly resulting from the deep indentations of Newfoundland’s Conception and Trinity Bays, and arrived at the coast of East Asia. Some believed he had reached another fabled island, the Isle of Seven Cities, thought to exist in the Atlantic.

There were also reports Cabot had found an enormous new fishery. In December 1497, the Milanese ambassador to England reported hearing Cabot assert the sea was “swarming with fish, which can be taken not only with the net, but in baskets let down with a stone.” The fish of course were cod , and their abundance on the Grand Banks later laid the foundation for Newfoundland’s fishing industry.

Third Voyage (1498)

Henry VII rewarded Cabot with a royal pension on December 1497 and a renewed letters patent in February 1498 that gave him additional rights to help mount the next voyage. The additional rights included the ability to charter up to six ships as large as 200 tons. The voyage was again supposed to be mounted at Cabot’s expense, although the king personally invested in one participating ship. Despite reports from the 1497 voyage of masses of fish, no preparations were made to harvest them.

A flotilla of probably five ships sailed in early May. What became of it remains a mystery. Historians long presumed, based on a flawed account by the chronicler Polydore Vergil, that all the ships were lost, but at least one must have returned. A map made by Spanish cartographer Juan de la Cosa in 1500 — one of the earliest European maps to incorporate the Americas — included details of the coastline with English place names, flags and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.” The map suggests Cabot’s voyage ventured perhaps as far south as modern New England and Long Island.

Cabot’s royal pension did continue to be paid until 1499, but if he was lost on the 1498 voyage, it may only have been collected in his absence by one of his sons, or his widow, Mattea.

Despite being so poorly documented, Cabot’s 1497 voyage became the basis of English claims to North America. At the time, the westward voyages of exploration out of Bristol between 1496 and about 1506, as well as one by Sebastian Cabot around 1508, were probably considered failures. Their purpose was to secure trade opportunities with Asia, not new fishing grounds, which not even Cabot was interested in, despite praising the teeming schools. Instead of trade with Asia, Cabot and his Bristol successors found an enormous land mass blocking the way and no obvious source of wealth.

- Newfoundland and Labrador

Further Reading

Douglas Hunter, The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot and a Lost History of Discovery (2012).

External Links

Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador A biography of John Cabot from this site sponsored by Memorial University.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography An account of John Cabot’s life from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Recommended

Giovanni da verrazzano, jacques cartier, sir humphrey gilbert: elizabethan explorer.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

John Cabot (or Giovanni Caboto, as he was known in Italy) was an Italian explorer and navigator who was among the first to think of sailing westward to reach the riches of Asia. Though the details ...

John Cabot (Italian: Giovanni Caboto [dʒoˈvanni kaˈbɔːto]; c. 1450 - c. 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer.His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII, King of England is the earliest known European exploration of coastal North America since the Norse visits to Vinland in the eleventh century. To mark the celebration of the 500th anniversary ...

John Cabot (born c. 1450, Genoa? [Italy]—died c. 1499) was a navigator and explorer who by his voyages in 1497 and 1498 helped lay the groundwork for the later British claim to Canada. The exact details of his life and of his voyages are still subjects of controversy among historians and cartographers.

John Cabot (a.k.a. Giovanni Caboto), merchant, explorer (born before 1450 in Italy, died at an unknown place and date). In 1496, King Henry VII of England granted Cabot the right to sail in search of a westward trade route to Asia and lands unclaimed by Christian monarchs. Cabot mounted three voyages, the second of which, in 1497, was the most ...

John Cabot was a Venetian explorer and navigator known for his 1497 voyage to North America, where he claimed land in Canada for England. ... On June 24, 1497, 50 days into the voyage, Cabot ...

John Cabot (about 1450-98) was an experienced Italian seafarer who came to live in England during the reign of Henry VII. In 1497 he sailed west from Bristol hoping to find a shorter route to Asia, a land believed to be rich in gold, spices and other luxuries. After a month, he discovered a 'new found land', today known as Newfoundland in Canada.

Overview. In 1497 John Cabot (1450?-1499?), an Italian explorer sailing for England, reached land somewhere in the northern part of North America. Although unsuccessful in his attempt to reach Asia, his landfall gave England a territorial claim in the New World that would be the basis for her eventual colonization of parts of that continent.

John Cabot, orig. Giovanni Caboto, (born c. 1450, Genoa?—died c. 1499), Italian navigator and explorer. In the 1470s he became a skilled navigator in travels to the eastern Mediterranean for a Venetian mercantile firm. In the 1490s he moved to Bristol, Eng., and, with support from city merchants, he led an expedition in 1497 to find trade routes to Asia.

Historians have debated the voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot who first discovered North America under the reign of Henry VII. The primary question was who [John or Sebastian] was responsible for the successful discovery. A 1516 account stated Sebastian Cabot sailed from Bristol to Cathay, in the service of Henry VII; environmental hardships ...

by World History Edu · February 6, 2024. John Cabot, born Giovanni Caboto around 1450 in Genoa, Italy, was an Italian explorer and navigator known for his voyages across the Atlantic Ocean under the commission of Henry VII of England. This exploration led to the European discovery of parts of North America, believed to be the earliest since ...

Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol's Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol, 23 Nov 2016), ISBN 0995619301, 104 pp., 71 illustrations, £11.99 rrp. Also available as a free ebook from archive.org and the Bristol Record Society.

The Matthew of Bristol and the financiers of John Cabot's 1497 voyage to North America. By Evan Jones. English Historical Review, Vol.121, No.492 (2006). Abstract: The Matthew of Bristol is the vessel in which the Genoese explorer, John Cabot, sailed with his Bristol companions on their 1497 voyage of discovery to North America.Yet, despite the fame of the voyage and the ship, little has ...

Evidence that a Florentine merchant house financed the earliest English voyages to North America, has been published on-line in the academic journal Historical Research.. The article by Dr Francesco Guidi-Bruscoli, a member of a project based at the University of Bristol, indicates that the Venetian merchant John Cabot (alias Zuan Caboto) received funding in April 1496 from the Bardi banking ...

Like Cabot's first voyage, little is known about his third and final trip to America, except for the fact that it was well-provisioned. Presumably, John Cabot's goals for this mission were to gain ...

Over the years, the exact location of John Cabot's 1497 landfall has been a great subject of debate for scholars and historians. "Discovery of North America, by John and Sebastian Cabot" drawn by A.S. Warren for Ballou's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, April 7, 1855. From Charles de Volpi, Newfoundland: A pictorial Record (Sherbrooke ...

John Cabot, an Italian navigator and explorer, holds a significant place in British heritage due to his pioneering voyage to the coast of North America in 1497. Commissioned by King Henry VII of England, Cabot's expedition marks the earliest-known European exploration of coastal North America since the Norse visits to Vinland in the eleventh ...

I In 1497, John Cabot (Giovanni Cabotto) set off on a voyage to Asia. On his way he, like Christopher Columbus, ran into an island off the coast of North America. As a result, Cabot became the second European to discover North America, thus laying an English claim which would be followed up only after an interval of over one hundred years.

Abstract. The Matthew of Bristol is the vessel in which the Genoese explorer, John Cabot, sailed with his Bristol companions on their 1497 voyage of discovery to North America. Yet, despite the fame of the voyage and the ship, little has been known about the Matthew, or about Cabot's relationship with his English backers.This has encouraged the proliferation of mythic representations of the ...

'New Found Land' just two years after the first voyage of Venetian explorer John Cabot who sailed from Bristol to 'discover' North America in 1497. Cabot led a second, larger, expedition ...

Over the years, the exact location of John Cabot's 1497 landfall has been a great subject of debate for scholars and historians. "Discovery of North America, by John and Sebastian Cabot" drawn by A.S. Warren for Ballou's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, April 7, 1855. From Charles de Volpi, Newfoundland: A pictorial Record (Sherbrooke, Quebec ...

Cabot, John, d. 1498, Cabot, Sebastian, 1474 (ca.)-1557 Publisher London, The Argonaut press Collection university_of_illinois_urbana ... English "This edition of The voyages of the Cabots is the seventh publication of the Argonaut press and is limited to 1050 copies on Japon vellum ... printed by Walter Lewis, M. A., at the University press ...

Historical Map of North America & the Caribbean (24 June 1497 - John Cabot's expeditions: Columbus' discoveries created excitement in Europe and in 1496 Henry VII of England agreed to sponsor another Italian navigator, John Cabot, in his own explorations. Cabot arrived off the coast of Newfoundland in 1497, possibly—his voyages are poorly documented—returning to explore the coast of ...

John Cabot (a.k.a. Giovanni Caboto), merchant, explorer (born before 1450 in Italy, died at an unknown place and date). In 1496, King Henry VII of England granted Cabot the right to sail in search of a westward trade route to Asia and lands unclaimed by Christian monarchs. Cabot mounted three voyages, the second of which, in 1497, was the most ...