- BMI Film & TV Award winners

- DVD Exclusive Award nominees

- Emmy Award winners

- Golden Globe Award nominees

- IFMCA Award winners

- Saturn Award nominees

Jerry Goldsmith

- View history

- 1 Biography

- 2 Notable works, awards, and honors

- 3.1 Star Trek credits

- 3.2 See also

- 3.3 External links

Biography [ ]

Jerry Goldsmith began studying piano at the age of six, and was studying composition at age fourteen. He became acquainted with the legendary composer Miklós Rózsa , and attended his classes in film composition at the University of Southern California.

Goldsmith originally intended to become a concert hall composer, but soon realized that the infrequency of concert hall commissions would never satisfy his hunger to write music (much less pay the bills).

In 1950, he was employed as a clerk typist in the music department at CBS . It was there that he was given his first assignments as a composer for radio shows, such as Romance and CBS Radio Workshop . He would stay with CBS until 1960, having already scored some episodes of The Twilight Zone . He was hired by Revue Studios to score their Thriller series, which lead to further television commissions. He composed his first film score for the 1957 western Black Patch , which featured Star Trek: The Original Series guest actors Stanley Adams and Peter Brocco .

In 1962, Goldsmith was awarded his first Oscar nomination for his acclaimed score to the poorly-received John Huston picture Freud . At the same time, he became acquainted with influential film composer Alfred Newman, who, recognizing Goldsmith's talents, influenced Universal into hiring him to score the film Lonely Are The Brave in 1963. From then on, Goldsmith established himself as a leading name in American film music.

Jerry Goldsmith died of cancer in Beverly Hills, California. He was 75 years old.

Notable works, awards, and honors [ ]

Goldsmith won his only Academy Award for scoring the 1976 horror movie The Omen , which featured David Warner . He was also nominated for writing a song from that film called "Ave Satani". He had previously been nominated by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for his work in the acclaimed films A Patch of Blue (1965), The Sand Pebbles (1966, directed by Robert Wise and featuring Jon Lormer and Gil Perkins ), Planet of the Apes (1968, with James Daly , Lou Wagner , Paul Lambert , Billy Curtis , Jane Ross , Felix Silla , and designs by Wah Chang ), Patton (1970, with Carey Loftin and Lawrence Dobkin ), Papillon (1973, with Anthony Zerbe , Bill Mumy , William Smithers , Victor Tayback , Ron Soble , and Peter Brocco ), Chinatown (1974, with Perry Lopez , Roy Jenson , Noble Willingham , cinematography by John A. Alonzo , and stunts by Hal Needham ), and The Wind and the Lion (1975, with Brian Keith and Roy Jenson). He went on to earn nominations for scoring the films The Boys from Brazil (1978, with Walter Gotell , David Hurst , and Michael Gough ), Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), Poltergeist (1982, photographed by Matthew F. Leonetti ), Under Fire (1983, with Joanna Cassidy and Hamilton Camp ), Hoosiers (1986), Basic Instinct (1992), and L.A. Confidential (1997, with James Cromwell , Matt McCoy , and Steve Rankin ). His last nomination came for his work in the animated Disney film Mulan (1998, featuring the voices of Miguel Ferrer and George Takei ).

Goldsmith was additionally nominated for four Emmy Awards, winning all of them. Aside from the theme to Star Trek: Voyager (see below), he also won Emmys for scoring QB VIII (1974, with Michael Gough, Mark Lenard , and produced by Douglas S. Cramer ), the 1975 TV movie Babe , and Masada (1981). His other television scoring credits include episodes of Gunsmoke , Wagon Train , and Perry Mason , multiple episodes of The Twilight Zone and Thriller , and the opening themes for Dr. Kildare , The Man from U.N.C.L.E. , The Waltons , and Barnaby Jones (starring Lee Meriwether ).

Action epics such as Alien (1979) (for which he received a Golden Globe nomination), the Rambo films (1982, 1985, 1988, with Bruce Greenwood , Charles Napier , Steven Berkoff , Kurtwood Smith , and the first film photographed by Andrew Laszlo ), Total Recall (1990, with Ronny Cox , Marc Alaimo , Robert Picardo , Mel Johnson, Jr. , Roy Brocksmith , Lycia Naff , Robert Costanzo , Frank Kopyc , and Michael Champion ), Air Force One (1997, with Dean Stockwell and Robert Duncan McNeill ), and The Mummy (1999, with Erick Avari ) were scored by Goldsmith.

Other films he scored include Seven Days in May (1964, with Whit Bissell and Leonard Nimoy ) (for which he was also nominated for a Golden Globe), The Blue Max (1966, with Jeremy Kemp ), Our Man Flint (1966, with Peter Brocco, Chuck Hicks , and Roy Jenson), In Like Flint (1967, with Steve Ihnat , Yvonne Craig , Dick Dial , and James B. Sikking ), Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970, with Keith Andes and Ken Lynch ) Logan's Run (1976, with stunts by Bill Couch, Sr. , based on the novel by George Clayton Johnson ), The Secret of NIMH (1981, with Wil Wheaton ), Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983, with John Larroquette , Bill Quinn , Peter Brocco, William Schallert , Dick Miller , and Bill Mumy), The Russia House (1990), Six Degrees of Separation (1993, with J.J. Abrams ), Congo (1995, with Carolyn Seymour ), Hollow Man (2000), and The Sum of All Fears (2002, with James Cromwell and Bruce McGill ).

Goldsmith composed the soundtrack of numerous films for director Joe Dante : Gremlins (1984, with Zach Galligan , Keye Luke , Frank Welker , William Schallert, Kenneth Tobey , and Goldsmith himself having a cameo) (for which he won a Saturn Award from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films), Explorers (1985, with James Cromwell and Brooke Bundy ), Innerspace (1987, with William Schallert, Kenneth Tobey, Andrea Martin , and photographed by Andrew Laszlo), The 'Burbs (1989), Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990, with Zach Galligan, John Glover , Keye Luke, Kenneth Tobey, and again Goldsmith's cameo), Matinee (1993, with William Schallert), Small Soldiers (1998, with Kirsten Dunst , Frank Langella , Michael McKean , and Gregory Itzin ), and Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003, with Marc Lawrence , George Murdock , Ron Perlman , and Frank Welker). Also, with the exception of the first Gremlins , all of these films featured Star Trek: Voyager star Robert Picardo , and all of them featured two-time Trek guest actor Dick Miller in the cast.

In addition to his Oscar and Emmy achievements, Goldsmith received nine Golden Globe nominations, seven Grammy Award nominations, four nominations from the BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) Awards, and seventeen Saturn Award nominations (winning one). In 1999, he received a Hollywood Film Award in Outstanding Achievement in Music in Film from the Hollywood Film Festival. He also won an Annie Award for his work on Mulan , received a Golden Palm nomination from the Cannes Film Festival (for Basic Instinct ), received a Golden Satellite Award nomination (for L.A. Confidential ), and won fourteen BMI Film Music Awards, among several other honors.

In June 2016 , it was announced that Goldsmith would be honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame . [1] The star – the 2611th – was dedicated on 9 May 2017 . [2]

Association with Star Trek [ ]

Goldsmith was Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry 's original choice to compose the music for " The Cage ", which would have included the show's theme music . Goldsmith had to decline, however, as he was committed to other projects and he recommended that Alexander Courage (who was mostly an arranger, and often worked with Goldsmith in that capacity) write the score instead. ( Star Trek: The Motion Picture (The Director's Edition) audio commentary)

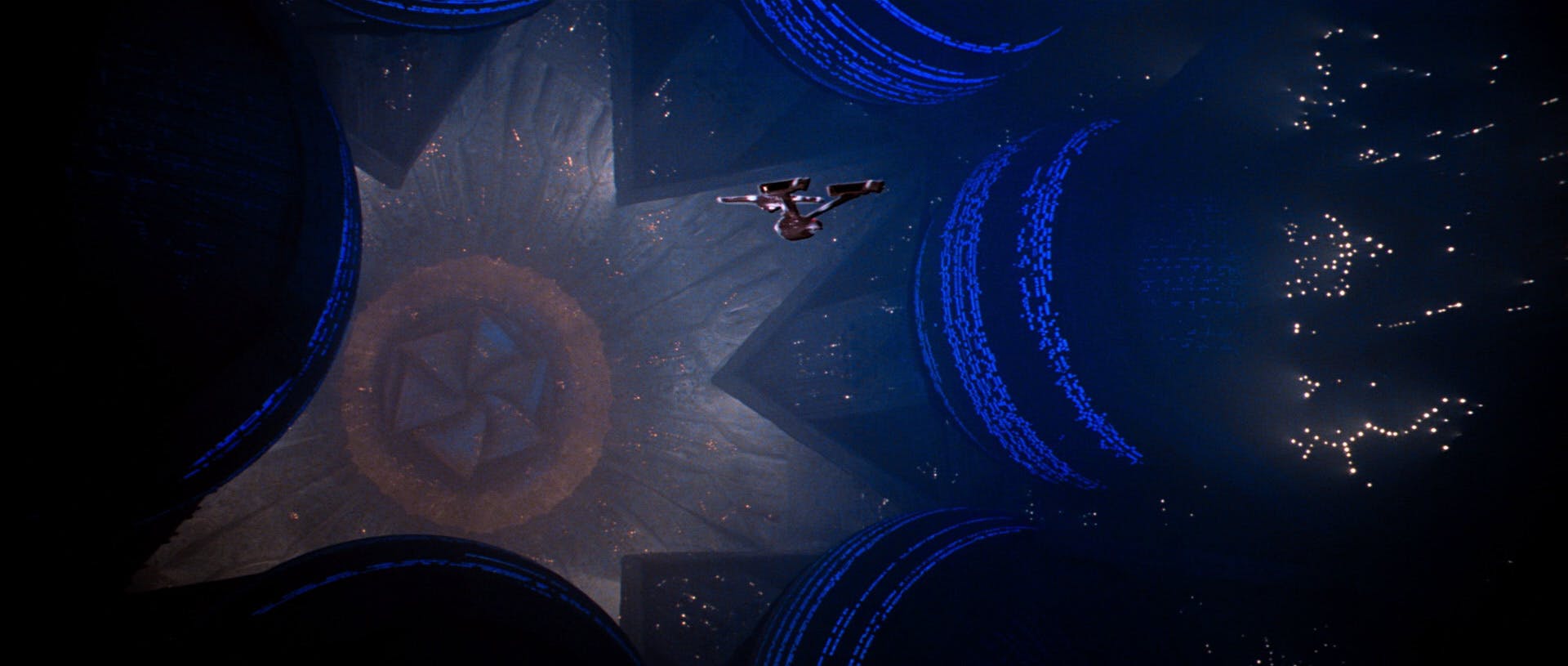

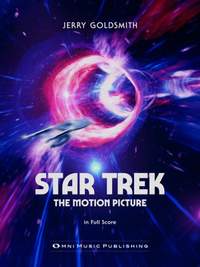

In 1979, Roddenberry offered Goldsmith Star Trek: The Motion Picture and the composer leaped at the opportunity. Here, Goldsmith was tasked with re-inventing a franchise and creating a brand new theme. Goldsmith himself remarked it was the toughest he ever wrote, and it remains a remarkable achievement. The Motion Picture also marked the second time Goldsmith worked with director Robert Wise ; Goldsmith previously scored The Sand Pebbles for Wise in 1966.

Beyond creating a new theme, Goldsmith also created new kinds of soundscapes in Star Trek: The Motion Picture , through the inventive use of unusual instruments, such as the "Blaster Beam". At the behest of Roddenberry, it was later adapted to become the signature theme for Star Trek: The Next Generation .

Goldsmith's other famous tune from the film, the "Klingon Battle Theme" was also reused in later Star Trek productions, most notably in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier and Star Trek: First Contact by Goldsmith himself, and in TNG : " Heart of Glory ", " The Bonding ", and (via stock footage) TNG : " Shades of Gray ".

Some initial music Goldsmith composed for The Motion Picture differed from the final product, particularly the fanfare written for the scene in which the refit USS Enterprise is revealed. The original score did not meet with Robert Wise's satisfaction and Goldsmith was asked to do the score over again. According to Goldsmith, Wise was displeased with the score because "there's no [ Star Trek ] theme." Although Goldsmith was "crushed", he came up with a revised score which did meet with Wise's approval that same night. ( Star Trek: The Motion Picture (The Director's Edition) special features – "A Bold New Enterprise")

Goldsmith's score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture earned him the eleventh of his eighteen Oscar nominations in the category of Best Music, Original Score. The score also earned him nominations from the Golden Globes and the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films.

During the 1980s and '90s, Goldsmith's orchestra often included tuba player Tommy Johnson , best known for the ominous theme music from Jaws . Goldsmith and Johnson collaborated on all of Goldsmith's Trek productions, with the exception of Nemesis , as well as such films as Executive Decision , Air Force One , and Mulan .

In 1989 , Goldsmith scored Star Trek V: The Final Frontier .

In 1992 , Goldsmith was approached by Paramount Pictures to write the main title theme for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine . Goldsmith commented " Yes, I was supposed to do that and I had a conflict and I couldn't ". ( The Music of Star Trek , p97)

In 1994 , he wrote the main title theme for Star Trek: Voyager , for which he won an Emmy Award ( Listen file info ). He later composed the scores for Star Trek: First Contact and Star Trek: Insurrection .

By the early 2000s, Goldsmith's health prevented him from working as much as he once did. He did, however, finish his work on the franchise with Star Trek Nemesis . This film also marked his third collaboration with British director Stuart Baird after Executive Decision (1996, with Andreas Katsulas ) and U.S. Marshals (1998). Nemesis marked their fifth collaboration in general, as Goldsmith composed two previous films on which Baird served as editor: 1976's The Omen and 1981's Outland (with James B. Sikking and Steven Berkoff).

After his death, a tribute was made to him on the special collector's edition DVD of Star Trek: First Contact .

Star Trek credits [ ]

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture

- Star Trek: The Next Generation (main title theme, all episodes)

- Star Trek V: The Final Frontier

- Star Trek: Voyager (main title theme, all episodes)

- Star Trek: First Contact

- Star Trek: Insurrection

- Star Trek Nemesis

- " Remembrance " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " Maps and Legends " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " Absolute Candor " (theme from Star Trek: Voyager )

- " Stardust City Rag " (theme from Star Trek: Voyager )

- " Nepenthe " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " Broken Pieces " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " Et in Arcadia Ego, Part 2 " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " The Star Gazer " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " Fly Me to the Moon " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " Farewell " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact )

- " The Next Generation " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact )

- " Disengage " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact ; Klingon theme)

- " Seventeen Seconds " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact )

- " No Win Scenario " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact )

- " Imposters " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact ; Klingon theme)

- " The Bounty " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact ; theme from Star Trek: Voyager ; Klingon theme)

- " Dominion " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact ; theme from Star Trek: Voyager )

- " Surrender " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact ; Klingon theme)

- " Võx " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact )

- " The Last Generation " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ; theme from Star Trek: First Contact )

- " Temporal Edict " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " No Small Parts " (theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture )

- " We'll Always Have Tom Paris " (theme from Star Trek: Voyager )

- " Grounded " (theme from Star Trek: First Contact )

- " Twovix " (theme from Star Trek: Voyager )

- " Crossroads " (theme from Star Trek: Voyager )

- " Mindwalk " (theme from Star Trek: Voyager )

See also [ ]

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture (soundtrack)

- Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (soundtrack)

- Star Trek: First Contact (soundtrack)

- Star Trek: Insurrection (soundtrack)

- Star Trek Nemesis (soundtrack)

External links [ ]

- Jerry Goldsmith at Wikipedia

- Jerry Goldsmith at the Internet Movie Database

- Interview at EmmyTVLegends.org

- 1 Abdullah bin al-Hussein

- More to Explore

- Series & Movies

Published Dec 7, 2023

Looking Back at the Music of 'Star Trek: The Motion Picture'

How Jerry Goldsmith tackled the majestic score for the Enterprise's first big screen adventure, in theaters 44 years ago today.

StarTrek.com / Charlotte Tegen

"I was miserable," admitted Jerry Goldsmith.

Four months from the December 7, 1979 release date of Star Trek: The Motion Picture , the composer only had a limited amount of footage and had to begin recording in a month. It was hardly an ideal situation, and it would get worse before it got better, but Goldsmith's score would go on to become an iconic part of Gene Roddenberry's creation.

StarTrek.com

The issues during The Motion Picture ’s production were far larger than the music. Paramount had given the film a budget of $46M and locked in the release date while there were still story problems, not to mention visual effects difficulties. Subsequently, the post-production process was manic, and Goldsmith was writing music as fast as he could with what little he had. But when he put his music in front of the orchestra to record, director Robert Wise was less than thrilled.

Recalling his thoughts on the 2001 DVD release of the Director’s Edition of the film, Wise said, "It's not working. I listened to the first couple of pieces and it didn't seem quite right to me. I got visions of sailing ships somehow.."

In the same behind-the-scenes interview, Goldsmith admitted, "I was crushed." Wise went onto explain his problem with the music — there was no theme. Specifically, there was no Star Trek theme.

The composer struggled on, but 10 days later, he played his new creation for the director. Upon hearing the next version, Wise approved and asked, "Why didn't you come up with that in the first place?" With the themes written, Goldsmith revised the cues he had previously recorded, and the score was on its way.

Goldsmith recruited original Star Trek composer Fred Steiner to write several cues based on the material, and November of 1979 saw the belated arrival of some of the film's effects sequences. The score was finally completed on December 2, and five days later, The Motion Picture left drydock.

While reviews were mixed across the board, Goldsmith's score stood out as a towering achievement, one that not only gained him his 12th Oscar nomination (he had previously won for 1976's The Omen ), but also one that would be an integral part of Star Trek' s future legacy.

One of the challenges Goldsmith faced was to compose a symphonic score that was different from John Williams' Star Wars compositions, which hit two years prior. Instead of the leitmotif device Williams utilized, Goldsmith employed his main theme as a backbone, using it to encapsulate an approach that combined the romance and mystery of space exploration. This was a new direction for Goldsmith, venturing into a more romantic idiom of scoring.

"He was definitely a modernist," said composer David Newman in the liner notes for La-La Land’s definitive release of the soundtrack. Newman, who played the violin on The Motion Picture , added, "I think Star Trek was a turning point for him. I think he realized he couldn't be a Planet of the Apes modernist and compose [for] films."

But The Motion Picture is still very much a Jerry Goldsmith score, especially in the way it adds esoteric instruments and electronic augmentation to the traditional orchestra, harking back to previous scores such as Planet of the Apes (1968) and Alien (1979). One of the signature sounds of the film is the blaster beam, the instrument which emits the harsh electronic tones for V'Ger . This was built and performed by Craig Huxley, using "a long piece of aluminum with metal strings strung the whole way over it and amplifiers under each string," as Goldsmith described it.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture

Goldsmith introduces his main theme in a thundering fashion, setting out his intent in the opening credits, which, in the La-La Land liner notes, film score expert Jeff Bond calls "a musical distillation of Roddenberry's utopian vision." In the same notes, Goldsmith himself echoed Roddenberry's original concept of Star Trek as a western, saying that it was no different than "the stirring music you'd play in a western as they're going across the plains... The only difference is you're going across the universe."

Goldsmith's theme conjures up a bold feeling of exploration, cutting a path through the stars with the Enterprise in its wake, while its B-theme suggests not only adventure but the connection between Admiral Kirk and the starship herself. Goldsmith expanded on this in "The Enterprise ," the show-stopping cue that scores the moment when Kirk and the audience first glimpse the brand-new refitted starship.

Almost as a contrast to the Federation's benign mission, the opening sequence introduced Goldsmith's theme for the legendary warrior race of Klingons. Setting a trend for other composers to follow, Goldsmith used the theme to summarize their barbaric and aggressive tendencies, with the Indonesian angklung and plucked strings leading the sharp and angled main melody. Interestingly, Goldsmith would return to this material for his score to Star Trek: First Contact , where it was turned on its head to become a heroic motif for the character of Worf.

Goldsmith's music for V'Ger explores the dynamics between the idea of a living machine — a contradiction in terms — and its quest to meet its creator, with a long-lined undulating melody conveying a mechanical feel but also suggesting that something else lies under the surface. The score also features a haunting ostinato for the Enterprise 's journey through V'Ger , and surprisingly, another motive, which is a minor-mode version of Ilia's theme, foreshadowing the union at the climax of the film.

Ilia's theme, which also appears as the overture —one of the last for a theatrical film for several decades — is the main love theme of the film, a gorgeous but delicate melody representing the Deltan's previous relationship with Commander Decker. Also in tune with V'Ger is the composer's fascinating theme for Spock, a truly alien melody that captures the character's unemotional state as he unsuccessfully attempts to purge his human emotions in the Kolinahr ritual, which Goldsmith juxtaposes with the V'Ger material to indicate their destinies may be intertwined.

An interesting anomaly is the lack of music referring to The Original Series . While Star Trek as a franchise is still musically defined by Alexander Courage's famous opening fanfare, Goldsmith requested to not use any of Courage's music. Although, he later relented and allowed Courage to write an arrangement of his main theme to score two sequences where Kirk narrates the Captain's Log. The result is a pair of brief cues that present the theme in a very subdued manner, a far cry from its use in the original series but appropriate for the seriousness of the Enterprise 's mission.

Getty Images

Jerry Goldsmith returned to the franchise in 1987 when The Next Generation debuted, with the opening credits of the show successfully combining the Courage fanfare and the Goldsmith theme (something the composer would later do himself in 1989 for Star Trek V: The Final Frontier ). He composed music for three additional movies, as well as wrote the main title theme for Star Trek: Voyager . Whether it was for film or television, where Star Trek was concerned, Goldsmith was omnipresent.

Sadly, Jerry Goldsmith passed in 2004. However, his music for Star Trek and particularly The Motion Picture continues to live on, through the wonderful La-La Land soundtrack release, as a concert staple, and in the hearts of Star Trek fans across the universe. For them, there is no comparison.

Get Updates By Email

This article was originally published on September 18, 2019.

Charlie Brigden (he/him) is a writer specialising in film music and is based in Wales in the U.K. He has a rather large tattoo of the TOS Enterprise and can be found on Twitter @moviedrone.

- Behind The Scenes

Jerry Goldsmith (1929-2004)

- Music Department

Additional Crew

IMDbPro Starmeter See rank

- 43 wins & 97 nominations total

- Music Department (uncredited)

- In Production

- theme music composer

- additional themes

- 'star trek first contact end title'

- 'star trek first contact main title i locutus' ...

- 11 episodes

- Original Star Trek Themes by

- composer: "Universal Theme" Universal Animation Studios logo (uncredited)

- music by: "Ambassador" and "Trial Run" from "The Final Conflict" Original Soundtrack

- composer: additional music

- music composer

- composer: themes from "Explorers", "Innerspace" and "Gladiator - Unused Score"

- composer: original themes

- composer: "Universal Theme" (uncredited)

- Composer (music by)

- in remembrance of

- additional interviewee

- scoring tasks (uncredited)

Personal details

- Jerrald K. Goldsmith

- February 10 , 1929

- Los Angeles, California, USA

- July 21 , 2004

- Beverly Hills, California, USA (lung cancer)

- Spouses Carol Heather Goldsmith July 23, 1972 - July 21, 2004 (his death, 1 child)

- Joel Goldsmith

- Other works The song "No One Like You" on the Sarah Brightman CD "Timeless" (Track 1) is a vocal version of the "Theme from Powder" (1995) with lyrics by David Zippel .

- 1 Biographical Movie

- 1 Portrayal

- 1 Interview

- 16 Articles

Did you know

- Trivia He considered Star Trek: First Contact (1996) the best Star Trek film he ever scored.

- Quotes If our music survives, which I have no doubt it will, then it will be because it is good.

- Trademarks Best known for composing the music for the Star Trek franchise

- The Omen ( 1976 ) $25,000

- When did Jerry Goldsmith die?

- How did Jerry Goldsmith die?

- How old was Jerry Goldsmith when he died?

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Add demo reel with IMDbPro

How much have you seen?

Recently viewed

- April 19, 2024 | Exclusive First Look At Artwork From ‘Star Trek: Celebrations’ – IDW’s One Shot Comic For Pride Month

- April 19, 2024 | Podcast: All Access Faces The Strange On ‘Star Trek: Discovery’

- April 18, 2024 | Lost Original USS Enterprise Model From ‘Star Trek’ Returned To Gene Roddenberry’s Son

- April 18, 2024 | Recap/Review: ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Gets The Timing Right In “Face The Strange”

- April 17, 2024 | Watch: Things Get “Odd” In ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Trailer And Clip From “Face The Strange”

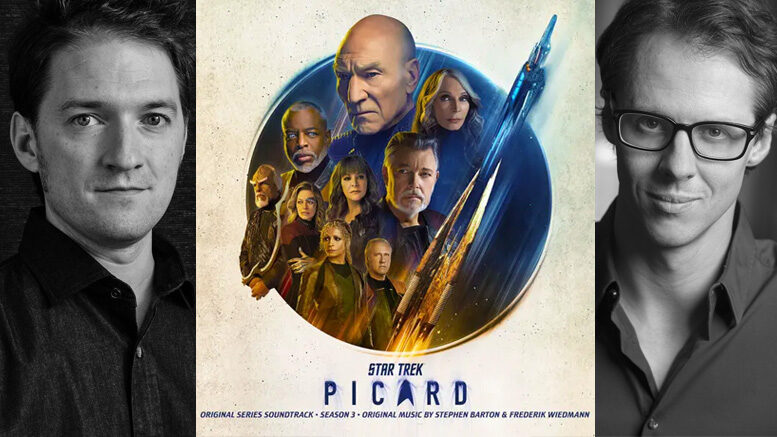

Interview: ‘Picard’ Season 3 Composers On How They Are Reviving Classic Star Trek Music

| March 29, 2023 | By: Jeff Bond 50 comments so far

Paramount+’s recent Star Trek series Discovery and Picard have employed composer Jeff Russo to bring a modern edge to the shows while occasionally tipping a hat toward the thematic material of earlier Trek composers. But for Picard’s third season, showrunner Terry Matalas recruited British composer Stephen Barton, who worked with Matalas on SyFy’s 12 Monkeys , and Frederik Wiedmann (who’s scored everything from numerous DC animated movies to children’s TV shows and video games). The pair were given a specific mission: resurrect the bold, in-your-face orchestral style of the classic Star Trek movies, with major callouts to themes by Jerry Goldsmith, James Horner, Cliff Eidelmann, and even Leonard Rosenman. The result is some of the most exciting Star Trek scoring in years, music that has fans fired up for the imminent soundtrack release. TrekMovie sat down with the composers for an extensive discussion to talk about this classic musical approach and how they tackled it.

Who do you guys answer to on Picard in terms of scoring? And what was the brief, just in general, when you started?

Stephen Barton: Terry Matalas and I had talked about Trek for a long time, actually, particularly when 12 Monkeys was going on. He’s a veteran of Star Trek —he was a PA on Voyager and then worked as a writer on Enterprise . So he’s kind of come up through the ranks on the Star Trek side. And when I first started working with him, five, six years ago, it was something we chatted about quite early on. I think even when I first met him for lunch on the Paramount lot it was one of the things we chatted about. And add the fact we had a shared past in that sense, in terms of what Trek we had grown up with, which was for both of us a case of parents having seen the original series, but the first time we got a series of our own was really Next Generation and watching it as kids. He’s a little bit older, but I was watching it when I was like five or six. I think for both of us it was very much a defining point in our relationship with television and with media in general. Akiva Goldsman was still very much running Picard season two and Terry was very much involved at the beginning of the season as a writer but about three or four episodes in he split off to really look after season three, which was always going to be his baby.

Terry very much pitched it to us as this idea of, let’s look back to the whole of the franchise and let’s look back, really in-depth at the Horner and the Goldsmith scores. Let’s look back at Dennis McCarthy’s work. Let’s look back at Ron Jones’ work, Cliff Eidelman, and Leonard Rosenman, looking back at all of it, let’s take a step back and look at what it means. And because the other thing was, obviously with Trek there’s been so many iterations and things used from one version into another, sometimes without a sense necessarily of what specifically something means. Even the Alexander Courage theme, this is a general Trek theme now and even was, I think, by the third movie, with the idea that this isn’t a specific thing; this is a wider theme. So, I think that was always what we were talking about.

And then as we got through the season, we were about six episodes in and one of the things we set out to do at the very outset was score it all. We weren’t going to do the typical TV thing of tracking, but the problem is, the shortest episode is 50-something minutes. So it’s 500 and something minutes of television. To most TV shows it would just be, we’re going to track half of this, or track a third of this or have three episodes in the middle which are just edited with some interstitials and things like that. And he was like, “No, no, I want to treat every scene of this like one of the scenes in the feature films.” And so, there are two ways to do that. Either you write a ton of music or… well, that’s basically the only way of doing it, really. So that was kind of the genesis of it. And we got about episode six, and I think I’d been on it for three months, I’d written about five hours of music, and was just dead, and we got to this point where we’re like, do we sacrifice the vision? Do we sacrifice that? Or do we get some help? And mercifully, episode seven to nine had a ton of Freddie’s music in the temp track. Because I think that’s one of the things that Drew Nichols, our editor, tried to do-he tried to temp with not Star Trek music, just to be able to get a lens on it, that was different to just putting Trek music wall to wall, which is obviously incredibly easy to do, because there’s so much of it. So Freddie came in and saved the day and took two episodes over and knocked them out of the park, and actually really allowed me to do what I want to do, which is to land the last 30 minutes of the final episode.

Frederik Wiedmann: I was just looking at the minutes for the final episode and I’m counting 55 minutes of music. In one episode of TV.

Frederik Wiedmann, Drew Nichols, Terry Matalas, and Stephen Barton (center four L-R) during Picard scoring session at WB Eastwood scoring stage

Since you mentioned Ron Jones, did you discuss the whole Rick Berman aesthetic versus what Matalas wanted? Because even though the scoring is different for the first two seasons of Picard , there’s a lot of active music, but this in particular, it’s very upfront in the mix and hits things. It is more of a movie aesthetic or a Ron Jones Next Generation aesthetic, as opposed to what the TNG music turned into by season four or five.

Barton: Yes, we discussed this at length. It wasn’t necessarily always even with the Ron Jones stuff what the music was doing in terms of harmonically or thematically, it was just in the way it’s paced and the way it’s scored. And I went back and watched what for me is the pinnacle of season three of Next Generation —at the end of “Best of Both Worlds, Part One,” the end of season three, which for me was ingrained in my mind in the summer of 1990. You have music that’s very overtly scored, it goes right for the jugular, it’s not holding back at all, but it works and it’s not full of music that you separate from the picture, it just is part of it. And so, scoring like that, that it’s okay to be big and it’s okay to go off to moments. And funny enough, I think in episode three, we had a big homage—there’s a big sequence with the first time Vatic fires the weapon, that’s very much an homage to Ron Jones throughout that whole sequence. It just goes there and it says, let’s turn the burner up to 10 and go maximum in terms of the way it’s scored. It’s okay to be big and it’s okay to make bold statements and okay to play melody. And I think that was very much the focus, because that’s what we loved from the Trek both Terry and I remember; that’s kind of a hallmark of it. And Freddy has a number of massive moments in episode seven that are very, very similar, that were just moments where you play it.

Wiedmann: It’s funny, when I watch old movies, including all Star Trek , I’m always baffled by how little music there is actually, in an episode or a movie, how much space there was back then, that was okay. Even when you watch a James Bond movie from the Sean Connery-era Bond, there is so little score in the entire movie. And when it comes, it’s big. It’s bold, and it has a very distinct purpose. I think the aesthetics have changed a lot over the past 20 years in terms of scoring movies, especially in the sci-fi genre, where there’s a lot more music now, and a lot more subtle stuff in between. What used to be just empty space and ambiance now has something like a little pulse or something going on to keep the tension going, that we just didn’t do back then. And I think one of the big challenges in this particular Trek was how do we make it feel like the old ideas, and the old sonic templates for Star Trek while taking it into this current time of scoring? And I think that the response so far has been fans have absolutely noticed how much we go back to the roots of Star Trek sounds while also kind of giving it this modern edge I think it needed.

You have, I think, at least five or six themes that are preexisting, very specific melodies. And then you provide one major new one, I know that there are other pieces of new material, too, that you guys develop, but you have a theme for the Titan that is in the end title. So first, tell me a little bit about developing that. I was talking to someone who’d seen the early episodes before I had and he said, “They’re playing James Horner music.” And when I heard this theme, I realized the theme is not James Horner’s, but the setting it’s in is very evocative of Horner.

Barton: Yeah, that was 1,000% the goal with that. I think the thing that Horner brought to Trek , which I think some people would say is not in the Goldsmith scores—but I think it is, it’s just a lot more buried—is that kind of nautical thing, the militaristic feeling, but it is a very specific, militaristic thing of very much feeling that these ships are just boats in space. Everything from the very classical horn kind of harmonic series, like we’ve got two horns in pairs going up and down the harmonic series, those sorts of motifs, they have a very English feel, and that was something that Horner was very interested in. He was obviously an anglophile and I had the pleasure of meeting him once, actually, only at Abbey Road one time, but I think that that part of Trek was something we felt had been put aside a little bit. It wasn’t that we wanted to necessarily turn it back to being Wrath of Khan but it’s just acknowledging the fact that whilst this is a ship of exploration, it’s still a military command structure, there’s still danger, and I think that the Horner scores for me (danger being one of his motifs, literally , but we then do use his danger motif), it was one where we talked at length about it as, “This is the strongest of spices,” in terms of its musical presence, and I think that’s why James Horner liked it. It’s just such a bold statement, that to not use it to us was almost disrespectful. We’re not going to plaster it everywhere, but I think when we’re in the nebula, there is obviously a bit of a callback to the Mutara Nebula cues.

And so the Titan theme, I think I looked back through a lot of the orchestration, and had access to a fair number of the written scores and I was really looking about how it was constructed. And what was really interesting about Horner’s scores is how he works with limited resources. You get a sense of a very full sound playing, but it isn’t tutti, it’s not wall-to-wall, whereas the Goldsmith scores tend to be very dense, there tends to be a lot going on. And virtually everybody is doing something—during the main title, I don’t think anyone has any bars’ rest in the whole piece, they’re all doing something, whereas the Horner scores are often quite stripped back, very pointillistic, and very focused in their orchestration. There might be quite complicated things, so you have these violin arpeggio figures and I was having to sort of consult on whether they were even playable, because some of them were trying to do some augmented chord stuff that was a little tricky under the fingers. So I think that was the overriding thing with the Titan theme; it was very much an homage to James Horner versus the rest of Trek stuff, the Jerry Goldsmith stuff.

Here is the brilliant @ComposerBarton conducting his Titan theme with all those wonderful nods to Horner in his arrangement. String section only. It’s been stuck in my head for over a year. #StarTrekPicard pic.twitter.com/f5YCKXI6MS — Terry Matalas (@TerryMatalas) March 4, 2023

So did you sit down and discuss or map how you were going to employ all these themes? Because you’ve got Goldsmith’s March theme, which became the Next Generation theme; you have his First Contact theme, and you have that motif that’s actually from Star Trek V [the “Busy Man” motif from the cue of the same name], and the Klingon theme—and it’s obvious how you’re going to use the Klingon theme, but the other themes, you’re using them but not necessarily the way they were used by Goldsmith. So how did you decide where you were going to apply these themes?

Wiedmann: For my episodes, in particular, it was really all Terry’s roadmap. He’s got an incredible knowledge of Star Trek music, going back to the beginning of it, more than anybody I’ve ever met. And Terry gave us this specific and detailed kind of map, with, “This theme here, I want this thing here.” And he and the editor Drew, they kind of created this roadmap for us where things needed to be dealt with, small adjustments based on our creative ideas that the music had to adjust to, as we were writing. But in general, I would give Terry all the credit for placing the moments and the thematic ideas from the old Trek into the right pivotal places.

Barton: The “Busy Man” motif [from Star Trek V: The Final Frontier ] came to represent a lot of the stuff to do with both Commander Data and then also it’s almost like a nostalgia theme. It’s used in a few places where it’s not specific to that, but it’s used in a couple of places where it’s used to introduce the First Contact theme. And that’s been something where, lots of people say, “Oh, it’s the First Contact theme, it represents first contact. And to me, actually, when you look at the way Goldsmith uses it, the most poignant usage of it for me is in the scene where [Lily, the Alfre Woodard character], is seeing Earth from space for the first time. When she points a phaser at Picard and he gets her to put it down, and he says, “Okay, you’re really on a spaceship.” So for me, that theme always represented the love of spaceflight, and for me what I think Goldsmith was so good at doing was finding themes that can play from different perspectives. So, in those sequences, it’s playing both from the perspective of the audience looking through the crew’s eyes, like you’re going back to this great historical event, but also then you’re looking at the perspective of Zefram Cochrane and you’re looking at all these people with the goal of spaceflight ahead of them.

So, for me, that was always the “nostalgia for spaceflight itself” theme. And so that’s a lot of why we use that in the end credits. And also partly because it was one of those ones where we just felt that theme deserves to be heard more. We put it on the end credits because we felt that it just said something in a really nice way; that it said a lot more about what we were trying to say about the season to the audience. Then the Titan theme, I think very much was looking towards the same thing, where the original Jerry Goldsmith march became very much the Enterprise theme and very much represented the ship and its crew, and we knew we needed a theme for the Titan to do the same thing. This is the Titan and its crew, and obviously, there are places we then take that we haven’t shown yet, so very much that has a purpose and that is going somewhere.

Frederik Weidmann during a Picard scoring session

I think there’s some variation, at least one variation early on of the First Contact theme, something where it’s presented in a way that hasn’t been done before. So obviously, you’ve got access to the written scores for all this material, but have you internalized any of it enough so that you can just go ahead and write that? Or do you always need to refer to the written scores?

Barton: Really good question. Some I have internalized, because some of the genesis of that music and some of the influences on that music, I would certainly count as influences my own, particularly in some of the lesser-known influences, some of the English composers particularly. Growing up with a lot of English choral music and things like the Walton Henry V score, that’s not a million miles away at times from some of the stuff Horner was doing in terms of some of the ways it’s built, and particularly the horn writing. I think that’s one of the hallmarks, but it draws from other influences, too. But there’s a very Waltonian thing in there. And it’s funny with the Shakespeare reference, which plays a lot into certain parts of Trek , and I don’t think that’s an accident in the sense of how it’s scored. So I think that stuff comes a lot more naturally. I find the Goldsmith stuff harder to work with in terms of how it’s built, largely because it’s so heavyweight. He built the big sound before anyone else does. When we sometimes think of combos in the ‘90s and 2000s, of doing the big wall of noise and synths and stuff like that, he was doing it well before then. It’s very much that use of the whole spectrum, and the difficult part of that is time. Building those really dense scores takes a while. I can’t really rush it. And we just didn’t have very much time.

Wiedmann: I can tell you that there’s a short synth-only theme from Goldsmith that we’re using in the later episode for a very particular character. And it took me ages to make that sound out of my synthesizer. There’s probably just a patch Jerry had on some old keyboard, but I had to create it to make it feel just like that, and it took me way longer than dissecting an actual orchestral score. It’s a theme played with a very specific synth sound that fans will be able to tell exactly who I’m talking about when they hear it, so I really can’t talk about it because that hasn’t aired yet.

There’s a specific sound in movies you hear a lot for the past decade. Supposedly, Hans Zimmer invented it, but I’m not necessarily sure that he did. It’s this thing we just call the “ Braaam .” It’s this big bass noise that’s in Inception . But I was thinking actually, that this almost goes back to the blaster beam Goldsmith used for V’ger in Star Trek: The Motion Picture . That was actually the first time that kind of approach was used, and so it’s unique and specific to that. And I was thinking, “Oh, this is almost like blaster beam sound,” in some of the Shrike scenes.

Barton: Yes. Very much. I think we had exactly that conversation in February. It’s interesting where things like that become ubiquitous, and particularly in trailers. You could look at it two ways: on one side you could say, “Well, it’s a lazy trope of action writing.” But then you could also look at it as at its core it’s fundamental—you can go back to Carl Orff, Carmina Burana , if you play the orchestral version, not necessarily the two-piano version, it basically starts with that figure, and it’s one of those strong spices. I think the problem is that sometimes the tendency is to just chuck it in like a handful of chili peppers that blows your head off in two seconds. Fabulous, but then 10 minutes later, you’re like, it’s not a particularly good experience, and you’re regretting it. Gordie Howe and I talked about this a great deal on Star Wars as well, on the stuff we’ve been doing together, because if you just plaster the “Force Theme” everywhere, it loses any impact it will ever have. And it’s one of the most precious gems you can be entrusted with. So, I think even when Freddy and I were working out where we have these themes, literally sitting down and asking yourself, how should this be harmonized? Or how should this be accompanied and what’s the arrangement and making it not just a, “press button, Trek theme here,” but actually something that weaves in and out and feels cohesive with the narrative. We did a wonderful session with Craig Huxley, who plays the blaster beam, and we brought him in on the first episode to do some of the sound design around the Shrike.

Blaster Beam on the mixing board from Picard scoring session

Tell me about some of the other new material that you guys produced. And in terms of what you can talk about, there’s a number of dialogue scenes between people where you guys come in very quietly, and I was feeling like I was starting to hear melody, maybe for Roe and Picard. There’s something that plays I think when they’re having their final goodbye. And then you also hear it when Riker and Picard are looking at her Bajoran earpiece, her spycraft. And there’s a big birthing scene in the nebula that has this specific music for it. So how much specific character-centered material did you come up with?

Barton: That’s the family theme, which is what we eventually christened it. We went through many names, it didn’t really quite have a name at first. It’s something that is in the nebula birth sequence, but is hinted at throughout episodes earlier; you kind of hear hints at it. There’s a very, very oblique reference to it the very first time Beverly and Picard catch eye, that very slow string arrangement, but it’s very buried in there. And gradually we unfurled it, and it’s actually very much based off the Star Trek V “Busy Man” motif, but it’s upside down. So the flow takes the first three notes of that and then expands out and that was very much deliberate, and there are reasons for that, actually, that we can’t talk about yet. But there’s a very good reason for that. So the family theme, I think, was the big one, that we unfurl and kind of show for the first time in its full bent. And the other thing that Terry was very adamant about was that he wanted a theme that had a beginning and middle and an end that you play the whole way through. And then, funnily enough, we played it again in Episode Six, pretty much end to end as well.

Did you rerecord the end title, the arrangement of the First Contact theme and the march?

Barton: Those two aren’t rerecordings, those two are actually the original recordings. We went back and found the original—I forget what the mixes of them were off the top of my head, whether they were just LCRs or whether they were 5.1, I think I think First Contact was 5.1. And so they’re cleaned up to a degree so it is a bit of almost a remaster, but those two pieces, we didn’t rerecord. But that was largely because of time, because the other thing we inherited was very much a schedule from two seasons of previous TV, and to a degree of budgets as well. So we had one session in LA where we recorded, I think, 41 minutes in three hours—the musicians were just amazing; we could not have done this anywhere else. The L.A. musicians just killed it, but so many of them have played on so many of the scores. I think when [music contractor] Peter Rotter put the call out, we very much said what it is and we went out after people who had played on [the previous Trek movie scores] and said, “This is what we’re trying to do. We’d love you to come play.” So we had some players who I hadn’t seen in a number of years at the session, and we were actually very honored to have Steve Erdody, who’s playing cello. It was I think his last session pretty much not If not his last batch of sessions, but maybe his penultimate; I think Indy V might have been his last.

There are some pretty deep cuts and other things you referenced. For Daystrom Station you are referencing the orbital office complex music from Star Trek – The Motion Picture . And then there’s the whole museum scene where you even referenced Leonard Rosenman’s Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home theme, which I was really impressed by.

Barton: Leonard Rosenman and sneakily, there is the Horner Klingon theme on the top! That cue, I literally kind of sat down and said, “How many references can we get in?” Some of them are all completely obvious. But even there, we looked at how the harmony, for example, of the Voyager theme—because I find that to be one of the most restrained Goldsmith things where, so often where he pulls back, and really, you’re just dealing with two lines—there’s the melody line, and just a counter line, there’s no real harmony and everything’s implied, and I’m saying, “Okay, how can we even reference that and say we want to call back to that and the way it weaves through?” And so even when Jack gets his idea at the end, there’s a callback to the [ Voyager ] synth theme. I think it gave the studio a bit of a nightmare on the cue sheet because it’s like nine segments. And I think on the soundtrack that’s actually just gonna be listed as like eight Star Trek themes in the space of 90 seconds. And it was a challenge to make it make sense as well and not just feel like, “press button, press button…” I think if anyone’s going to criticize us, I think there’s just the thing of something Terry and I chatted a lot about, which is what would Jerry Goldsmith have done on the sequence? He has these great themes, and I think he probably would have gone to the approach of doing a million other things, and they would have pushed him back and said, “Well, we just want to hear the Voyager theme when you see it with Seven, so, please give us that.” But then he would have done it with consummate class. And that’s obviously the highest bar you can get, and I think in 25 years’ time, someone will say whether we reached that or not, but we certainly are not the ones to be the judge of that. So we’re just trying to do as well as we can.

The Fleet Museum brought back a lot of themes

I was getting choked up during the museum sequence. It is very literally fan service but it’s done very well and tastefully, and especially after everything else that has been built up it works beautifully. When I first started watching this I was initially kind of groaning because it seemed like it was diving so deep into, “we’re gonna do the lost son from Wrath of Khan .” And by the time I got to episode three or four, it all just was working so well, that I really felt like, “Okay, now they’ve earned all this.” And it stops becoming just, we’re gonna throw references to the fans, and it becomes much more like affection, and kind of earning all that and using it and in a really moving way. And the scores are a big, huge part of this. And it’s not just all the references, it’s the approach, the dynamic approach of having real action music and having big commercial playouts and all those things we associate with the older movies and shows.

Barton: Freddie has, without spoiling anything, a cue in episode seven that I think is eight minutes long or something, and it’s one idea. We were into the last three, four weeks, and we still have this pile of music to write, but it was one of those ones where you look at the sequence, and there’s no tracking, there’s no editing that can get you through this sequence. And that’s true of all of the back four episodes, seven through 10. I think that was the other thing we were very much thinking about when we were doing a lot of the action music. And Freddy and I chatted for quite a bit about this: the pacing, particularly when he gets to the final episode is like, how would you get bigger? How do you find places to pay this off? Funnily enough, a lot of where we found the answers to that was in the Goldsmith stuff. Because I think one of the Goldsmith hallmarks is his ability to use silence and his ability to write something big and massive. He’s a master of huge textures, but also a master of when to shut up and let something play. And so in all four of the final episodes, I think there are times we both realized you just pull back and you just let a moment be a moment, and you just be confident that we have the performances and we’re not trying to apologize for anything in terms of the production. The other thing we have is the visual effects are so much better now. We’re never trying to tell you something looks awesome because it probably does. And I think that a lot of the reason for modern film scoring and action scoring being the way it is, is because you see something so amazing on the screen. It’s almost like people are like, “Yeah, you don’t really need to add to it.” Whereas what you can do is realize that that’s not the total idea. The idea is, it’s okay to paint big themes around there, provided you do it in the right way and from the right perspective.

Wiedmann: I think this goes back to another question you had earlier, about new themes that I can’t talk about much. But there is a Jack Crusher idea, a musical idea that comes in the later episodes as his relationship with his father becomes more and more distinct. And his performance was so on the spot every single time that it just felt like you don’t want to do anything. So the theme for him in those particular ones is extremely subtle because he just does it all. So it’s really just very subtly supporting what’s going on, but the performance is so strong that you really don’t want to overstep that. There are so many instances of that throughout the whole season. I think that we’re almost like, “Let’s not break it.” Because it’s so good to begin with.

Frederik Wiedmann at a Picard scoring session

Yeah, that’s something I think people who didn’t grow up on it don’t understand about the older movies and television is that the music was the special effects and it was the sound design on a lot of these things. Before you came up with all these layers of Dolby sound and super sophisticated visual effects, the music had to sell all that stuff. And so it wound up doing so much more dramatically than you necessarily have to now. So what can you tell me about the soundtrack?

Barton: I think it’s about two and a half hours. That was a pretty heavy cull down from five hours. But I think we very much also wanted it to stand up as a listening experience in its own right. Gordy and I have Star Wars , we have a three-and-a-half-hour soundtrack. And at that point with these things, I’d be honored if anyone ever listens to it from start to finish. That’s the nicest compliment I think anyone could pay. But I think what we tried to do is to make it make sense. The funniest thing about the soundtrack is we didn’t cut it. And that sounds terrible. Terry cut it. We presented him a draft and we were chatting about it. And then the following morning, he’s like, “Yeah, I stayed up all night and cut this together,” and gave us a spreadsheet. Not only is he incredibly musical, he actually loves sitting at the back of the room while I write. He just loves it and will actually weigh in with suggestions. And most composers, I tell them that and they go white, and they’re like, “Are you kidding? The director’s in the back of the room while you’re writing, are you insane?” But he’s got such a good sensibility for it. And he’s not someone who says, “Yeah, go up, now go down,” or something like that, but he’s like a rather good composition teacher in a way without knowing it. Without having a background in music, he asks questions and says, “Well, is that theme, does that feel satisfying?” One of the things he often talks about is he wants his music to commit. And I think that’s what sets him apart from a lot of filmmakers in terms of how they handle music. He likes the music to go there. He’s like, “Commit to what you’re doing. Commit to shutting up, if you’re shutting up—get out, don’t leave some little pad.” He’s like, “Just shut up. Don’t be afraid to make the bold choices.” So that’s very much his directorial style. So he cut the soundtrack together, literally put it together and we listened through but I think we changed one track.

I’ve been into this music since I was a kid and it’s very much waxed and waned in terms of how much fun it is. This is very fun. And it definitely feels like something I want to listen to outside of the show and it helps drive the show and make it exciting. So, all props to Terry for being someone who wants that. Because it seems like filmmakers over the past few decades have been very conflicted about whether they actually want music as a real contributor, as a character, as opposed to just filling in the silence.

Barton: I think there was a process that filmmaking went through in the 2000s, and particularly with the boom of digital cameras, digital cinema, and the speed at which the process and the difference between the editorial versus where it’s gone to the Avid, and now we have the online and the offline and there’s the whole process of filmmaking. I think people thought we were going through a growing-up period where less music is more, and undoubtedly films were “less music is more,” and undoubtedly films did take the approach that the filmmaker wants that. That’s their prerogative. Now we’re passing through that and we’re getting to a place where it’s okay to be musical again. And I listen to a lot more scores now and hear a lot more scores where I actually like the music. And I think where it goes in the next 10 years will be very interesting. I think we’re starting to come to a place now where all of those languages are okay, provided you know what you’re doing with them. And so people are coming back to it and saying it’s okay to be melodic, it’s okay to have tunes, it’s okay to develop them. It’s okay to have a theme and call it something and have a leitmotif. That’s okay, again.

Wiedmann: One thing this whole experience working on this show taught me is there’s a lot of film music from 25 plus years ago, when you listen to it today, and you go, “This is not really what we’re doing anymore. This doesn’t really go with today’s aesthetic of moviegoers.” But anything that Goldsmith did, however old it may be, I think it holds up like nothing else to today’s standards. There’s nothing old or old-fashioned or cheesy sounding about it. It’s just like, “Holy crap, this is so fucking great.”

Barton: It’s taken 25 years to realize that.

Soundtrack announced

Lakeshore Records has announced they will be releasing the soundtrack for season 3 of Star Trek: Picard , containing 45 tracks . The digital release will arrive on April 20, the day of the season finale in April. You can pre-order the soundtrack on Vinyl for $35.98 , coming on May 12.

Jeff Bond is the author of The Music of Star Trek . He co-produced the 2012 15-disc box set of all the music from the original 196 6 Star Trek series and has written liner notes for releases of all the original Star Trek theatrical films from Star Trek: The Motion Picture to Star Trek: Nemesis .

Related Articles

Discovery , Interview

Interview: Wilson Cruz On How “Jinaal” Sets Up The Rest Of The Season For Culber On ‘Star Trek: Discovery’

Collectibles , Star Trek: Picard , TOS

Star Trek Coffees Launching In May With Several Blends

Interview: Wilson Cruz, Mary Wiseman And Blu Del Barrio On ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Season 5

Interview: Sonequa Martin-Green Talks Burnham’s Journey Into The Final Season Of ‘Star Trek: Discovery’

I would prefer more originality across the board myself

Agreed. It’s one thing to celebrate the franchises music, but this is a patch-work quilt of music written for entirely different scenes, characters, what-have-you. Can come over as leaning too much on prior musical greatness rather than doing something original that stands on its own two legs. It’s great to see the love and reverence for the scores however, and it’s incredibly well done. But it just seems an odd season/show to suddenly decide to celebrate Trek’s filmic music in particular, rather than it being a special Trek Anniversary or something. Too much reliance and memberberries!

Ditto. I don’t know why, but it really bums me out that they’re using the First Contact theme as the end theme — and I *love* that theme. But it just feels out of place and, well, borrowed/recycled here. I’d almost prefer the previous Picard theme (which wasn’t perfect). Or a new theme using some of the FC cues.

It’s kind of like how I felt the TMP theme for TNG. It’s one of my favourite movie themes, yet it never felt like it fit the show to me.

I thought combining the TOS theme and TMP theme to create the TNG theme was inspired. It easily became my favorite Star Trek theme. The classical opening narration continued Space The Final Frontier, and the music swells up. Just brilliant.

with all of these former “12 Monkeys” alum showing up on Picard, the one I would most like to see is Emily Hampshire ($chitt$ Creek)

She would be a wonderful addition. Shaw’s ex-wife, another captain, the event planner for Frontier Day, anything.

That would be awesome. But she’s a regular on” The Rig”, filmed about the same time as Picard. So it’s a slim chance at best.

It would be fantastic her and/or any number of 12 Monkeys alumni in addition to those who’ve already appeared. I just finished that show this week. One of the all time great series finales.

I was very much hoping Matalas would bring Hampshire into Trek as well.

Hopefully, he’ll have the opportunity to create as rich and wonderful character for her in a future show, limited series or movie as he did for Stashwick.

And yes, putting Stashwick and Hampshire back together in a scene would be the chef’s kiss.

Another captain would be nice. I want Shaw to be LGBTQ+.

Yep, also agree. I think she was the first person a lot of people thought of who would be involved in this season, even if it was for an episode.

I’d like to see Amanda Schull!

The score is wonderful. Plenty of legacy and plenty new that fits. I just love it all.

Same here. It’s magnificent.

Completely agree. It’s a fantastic score and I love it.

This was a very interesting read but I have to admit, I read the part where Barton was talking about composing for Star Wars and got very confused because when the interview said “Gordie Howe” my brain went “like the NHL player?”

Ha, you HAVE to be Canadian to know that name!

That’s what leapt to my mind also . ;)

No, American, but one of my headmates is Canadian and passed on his love of hockey to me. So I learned a lot about it, including about former players of some kind of note.

Picard season 3 has a great score so far. Job well done on that part . Just thinking about it even the weaker Trek movies are worth watching just for the score alone sometimes. I can just close my eyes , when one of the bad or boring bits crop up ,and just get enveloped by the music.

Absolutely!

Good point. I find this true as well. Generations and Insurrection , specifically.

My unpopular opinion is that I think that Star Trek III is the most under-rated Star Trek movie. It’s far from the best, but far from the worst. I love the music in that movie.

BTW: I noticed the TVH score played a bit when they showed the Bounty BOP in the previous episode.

To be honest, it’s probably the best “odd” Star Trek movie.

Found Matalas’ burner account!

Kidding aside, while this is an unpopular opinion, it shouldn’t be.

I absolutely love ST III, and have since seeing it in theaters. Sometimes I watch it even without watching WOK first. (But usually watch the two as one long movie).

Horner’s score for Star Trek III is my favorite of all the Trek movies new or old. Don’t get me wrong, Goldsmith’s score for The Motion Picture’s is amazing as is Horner’s work on Wrath of Khan. But, Search for Spock just rises that much more above in my book.

Your post just described my total viewing of TMP lol.

Star Trek 5 has awesome music despite the flaws of the film itself.

Awesome score so far on this show, definitely the best we’ve had in all of New Trek including the alternate timeline movies. I especially like what he’s saying about the Voyager theme in regard to Goldsmith’s restraint, and that it basically just has two lines and little harmony… but what they did with the theme *harmonically* for the museum scene was fan-tas-tic: it was just a few small harmonic tweaks (with a modified repetition of the three-note Voyager motif at the end), but it didn’t just make it weave through the scene, it really opened up the theme itself, made it deeper & more nuanced, and underscored Seven’s emotional state very well in that moment. That scene, in a masterful way, went far beyond fan service, and the composition was a big part of that success. Some absolutely brilliant composing for this season, for sure.

Just a quick word to praise this wonderful interview. It had great questions that elicited substantive and fascinating replies. Thank you!

Seconded. Great questions that really let these artists let loose.

Yes, thirded. Substantive discussion, no softballs.

For some reason, every time I hear a musical reference to the TOS movies, it takes me right out of the show. It’s like the auditory equivalent of seeing half the Titan’s crew wearing Monster Maroons instead of current uniforms. For whatever reason, I don’t think of it as “Star Trek” music, but as a historical signifier. I suppose it’s nothing more than a “me” problem in the end.

I feel the same.

The music is great

I’m am glad we are bringing back some awesome themes vs. the wallpaper music of TNG/VOY. Even the TNG theme was a watered down version of the TMP theme. Apart from the Borg music in TBOB I feel for the musicians as hard to utilize such forgettable music, glad to see they’ve decided to embrace the memorable TOS movie cues.

I love direction they’ve taken with the music this season. It’s fittingly more cinematic than the past few seasons and the rest of NuTrek. Great job!

Fantastic interview by Jeff Bond! I couldn’t have asked for better, just MORE!

Like so much of this season, the music harkens back to such a different and more nostalgic time and I love it! It’s a combination of nearly all the greatest Trek hits rolled into one.

I remember when the first teaser showed up on First Contact day announcing all the TNG actors were coming back and they played a piece of James Horner music in it. Many thought it was odd to include when in reality it was just giving us a taste of what was to come!

What I’ve enjoyed most is not the specific legacy cues, but how new music evokes the tone of certain older elements. It’s clear they wanted a James Horner “style” and they’ve captured it well.

Now we just need Strange New Worlds Season 1 Soundtrack!!

I preordered both the digital and the LP set (I wish there were a CD..) but I noticed the LP doesnt seem to have the 45 tracks as compared to the digital. Maybe I’m wrong.

Every time I talk to my brother about Picard, he says ‘it’s great… But how can they get away with using all that classic music and not even credit those guys?’

How could Horner rip off the same classical piece (sans credit) over and over again in his ‘work’? The opening of ALIENS and a sequence in PATRIOT GAMES are just two instances where he totally riffs on the ‘jog in a circle’ cue from 2001, which uses the Gayne Ballet Suite. And by riff, I don’t mean a bar or two, I mean MINUTES of score.

I am loving all the music in the sh0w, including the nods back to previous soundtracks. Star Wars has a very consistent feel to its music, since it all came from the same guy. I always thought that Star Trek had great themes, they just weren’t emphasized as well as they could be. This season is definitely flipping that around. Great article too. Thanks!

I think that musically they could have evoked trek simply by going deep into melody and percussion with new cues. There’s a bit of what Meyer called ‘getting kissed over the phone’ when music from another project gets tracked in, but it didn’t bother me on TOS, because the music was such a vital component, especially Kaplan’s DOOMSDAY MACHINE stuff as reused in IMMUNITY SYNDROME and OBSESSION.

Barton name-checked an absolute legend who deserves attention- Steve Erdody is one of the most prolific cellists in film music, and in classical circles as well. I love that this interview went to that depth on the creators and talent involved. If anyone is interested in hearing an interview with Steve, and to learn more about his work, check out this page: https://thelegacyofjohnwilliams.com/2021/07/26/stephen-erdody-podcast/

This was just such a great interview from you guys. Well done! Greetings from Germany!

I am a long-time fan of film scores, particularly Star Trek scores. These two composers knocked it out of the park. My ears and heart could not be more pleased.

Star Trek: First Contact (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)

22 November 1996 11 Songs, 44 minutes ℗ 1996 GNP Crescendo Records

More By Jerry Goldsmith

Featured on.

Apple Music Film, TV & Stage

You Might Also Like

Jay Chattaway & Jerry Goldsmith

James Horner

David Arnold

Sol Kaplan & Gerald Fried

Dennis McCarthy

Select a country or region

Africa, middle east, and india.

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Congo, The Democratic Republic Of The

- Guinea-Bissau

- Niger (English)

- Congo, Republic of

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- Tanzania, United Republic Of

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

Asia Pacific

- Indonesia (English)

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Malaysia (English)

- Micronesia, Federated States of

- New Zealand

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Solomon Islands

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- France (Français)

- Deutschland

- Luxembourg (English)

- Moldova, Republic Of

- North Macedonia

- Portugal (Português)

- Türkiye (English)

- United Kingdom

Latin America and the Caribbean

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Argentina (Español)

- Bolivia (Español)

- Virgin Islands, British

- Cayman Islands

- Chile (Español)

- Colombia (Español)

- Costa Rica (Español)

- República Dominicana

- Ecuador (Español)

- El Salvador (Español)

- Guatemala (Español)

- Honduras (Español)

- Nicaragua (Español)

- Paraguay (Español)

- St. Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- St. Vincent and The Grenadines

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turks and Caicos

- Uruguay (English)

- Venezuela (Español)

The United States and Canada

- Canada (English)

- Canada (Français)

- United States

- Estados Unidos (Español México)

- الولايات المتحدة

- États-Unis (Français France)

- Estados Unidos (Português Brasil)

- 美國 (繁體中文台灣)

Jerry Goldsmith’s 10 Most Indelible Scores

By Jon Burlingame

Jon Burlingame

- Dan Wallin, Oscar-Nominated and Emmy-Winning Music Mixer, Dies at 97 1 week ago

- ‘Law & Order’ Composer Mike Post Creates New Bluegrass and Blues Album (EXCLUSIVE) 3 weeks ago

- ‘Shogun’ Composers Spent More Than Two Years Composing Four Hours of Music 1 month ago

In honor of Jerry Goldsmith ‘s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, Jon Burlingame offers ten scores that best capture the late composer’s genius.

1. A Patch of Blue (1965) For the tender relationship between a blind white girl (Elizabeth Hartman) and the kindly black man (Sidney Poitier) she befriends, Goldsmith wrote a haunting, delicate score featuring piano and harmonica.

2. The Sand Pebbles (1966) Goldsmith’s first epic score, for director Robert Wise’s film about a U.S. gunboat in Chinese waters in the 1920s starring Steve McQueen. He evoked an Asian atmosphere with exotic instruments, and his love theme (“And We Were Lovers”) was recorded by artists from Andy Williams to Shirley Bassey.

3. Planet of the Apes (1968) A landmark in film-music history, this unearthly, Bartok- and Stravinsky-influenced soundscape strongly implied that Charlton Heston and his fellow astronauts were marooned on a far-off planet… when, in fact, they were on Earth all along.

4. Patton (1970) Goldsmith’s music illuminated the character of the World War II general (famously portrayed by George C. Scott), cleverly employing echoing trumpets to suggest his conviction that he had been present at every great battle in the history of warfare.

Popular on Variety

5. Papillon (1973) A virtual tone poem, this alternately gorgeous and harrowing score is a forgotten masterpiece of ’70s cinema music: beginning with a charming French waltz, ending with a crashing man-against-the-sea coda. Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman played inmates in the notorious Devil’s Island penal colony.

6. Chinatown (1974) Producer Robert Evans often said that Goldsmith “saved” Roman Polanski’s noirish drama set in 1930s L.A. Goldsmith wrote and recorded it in 10 days after an earlier score was discarded; his modernist ensemble included four pianos and four harps, and that sexy solo-trumpet theme is indelible.

7. The Omen (1976) Goldsmith’s sole Oscar winner was a choral-and-orchestral score for a summer popcorn movie about the Antichrist as a child, complete with Latin lyrics praising Satan. The composer’s music for Gregory Peck being attacked by dogs in a darkened cemetery is among the scariest of the decade.

8. Star Trek : The Motion Picture (1979) Perhaps the most familiar of all Goldsmith themes (used in many of the Enterprise crew’s subsequent film and TV appearances), this score established the heroic, symphonic sound of Kirk, Spock and company still in use today.

9. Poltergeist (1982) This Steven Spielberg-produced haunted-house movie about a little girl abducted into another dimension contains one of Goldsmith’s most brilliant musical ideas: a lullaby as its main theme, designed to remind listeners that a frightened child was at the story’s heart.

10. Basic Instinct (1992) Goldsmith’s most provocative and sensual score, for Paul Verhoeven’s infamous erotic thriller starring Sharon Stone, uses both orchestra and electronics to create moods of intense passion and edge-of-seat suspense.

More From Our Brands

Drake drops new kendrick lamar diss track with ai tupac, snoop dogg verses, inside the hidden world of vip perks at america’s marquee sports arenas, south carolina plans to buy women’s final four center court, be tough on dirt but gentle on your body with the best soaps for sensitive skin, two family guy holiday specials set to premiere on hulu in 2024, verify it's you, please log in.

Den of Geek

The 30 greatest film scores of Jerry Goldsmith

From The Mummy and Gremlins to Star Trek and Total Recall, we salute the work of the late, great Jerry Goldsmith...

- Share on Facebook (opens in a new tab)

- Share on Twitter (opens in a new tab)

- Share on Linkedin (opens in a new tab)

- Share on email (opens in a new tab)

Upon presenting a lifetime achievement award to famed composer Jerry Goldsmith, his equally esteemed contemporary Henry Mancini addressed the assorted Hollywood crowd, claiming “he keeps everyone honest… and frankly he scares the hell out of us.” It was a humorous observation but one laced with truth, for few film composers were as mercurial, dynamic or thrilling as Goldsmith.

Responsible for innumerable classic works, from Chinatown to Total Recall , and a pioneer in the integration of ethnic sounds and electronic samples with a full symphony orchestra, Goldsmith stakes a strong claim to being the greatest film composer who ever lived. Although he sadly passed away in 2004 his formidable legacy lives on, so here are his 30 greatest works that continue to inspire the soul and get the blood pumping.

30. The Mummy (1999)

Composed towards the very end of Goldsmith’s career, this richly engrossing adventure score proved the master of such things still had the magic touch, although Goldsmith himself reportedly hated working on the film. No matter: the intoxicating blend of typically thunderous action music, Egyptian instrumentation, creepy horror material and heartwarming romance made for one of Goldsmith’s late-career masterpieces, one that not only threw back to his earlier classics like The Wind And The Lion but a lost, lamented golden age of film scoring in general.

29. The ‘Burbs (1989)

Every so often, a usually serious film composer is obliged to let their hair down. Goldsmith’s partnership with mischievous director Joe Dante was one of the most unexpectedly fruitful of his career, the two men bouncing riotously silly and inventive musical ideas off one another that helped emphasise the satire of the movies in question; yet they didn’t come sillier than the score for The ‘Burbs . Here, Goldsmith throws out every trick in the book from sly spoofing of his own celebrated Patton score to blaring organ horror and utterly ridiculous electronic effects including breaking glass and wailing cats. It’s unashamedly daft but works brilliantly for the movie, heightening its sense of satirical fun no end.

Ad – content continues below

28. The Boys From Brazil (1978)

Another of Goldsmith’s great abilities was his ability to contort and manipulate pre-existing musical forms, thereby coming up with something truly twisted and unsettling. Franklin J Schaffner’s adaptation of Ira Levin’s novel, detailing the notorious Josef Mengele’s attempts to rekindle the Third Reich, sees Goldsmith brilliantly weaving Wagnerian and Straussian waltz movements around one another, a grandiose, decadent distillation of the Nazi regime’s lust for power that is at once both alluring and terrifying. However, much of the score is occupied by Goldsmith’s signature rumbling suspense material, off-kilter piano and terse strings reinforcing the dire threat of Mengele’s plan; truly one of the composer’s most innovative works.

27. The Edge (1997)