8 Highly Migratory Marine Species

Highly migratory marine species travel long distances in the ocean, often moving between continents. They include tuna, turtles, billfish, and swordfish.

Many marine species are migratory, meaning that they move between different waters in search of food, to spawn, or to escape from predators. Some move between the water column, while others are highly migratory. Highly migratory marine species are species that travel long distances across the oceans. They swim thousands of miles crossing international boundaries and even continents.

These fascinating migrations are not limited to a particular species but cut across all groups, from fish, sea mammals, and reptiles to seabirds. Unfortunately, due to their extensive movements, they are prone to overfishing and are among the most threatened species.

Below we will look at some of the highly migratory marine species.

Humpback Whale

Habitat: All oceans of the world Distance covered each year: 16,000 miles

The humpback whale belongs to the baleen whale suborder and gets its name from the hump on its back. They live in all the oceans and can grow up to lengths of 60 feet and 80,000 pounds in weight. Additionally, it’s also a fascinating animal to watch. They are active and often jump out of the water, slapping the surface with their fins. It is also vocal and known for its courtship songs.

These whales are well known for their long-distance migrations. During summer, humpback whales migrate to feed in the cold productive waters near the poles. In the winter, they migrate to the warm waters to mate and give birth. Humpbacks are powerful swimmers and swim up to 16,000 miles yearly.

Interestingly, despite traveling, feeding, and mating in big groups, these whales are typically loners and prefer to travel alone or in small groups of two to three. In these situations, a pod can consist of a mother whale and her baby. Sometimes two or three whales form a temporary alliance.

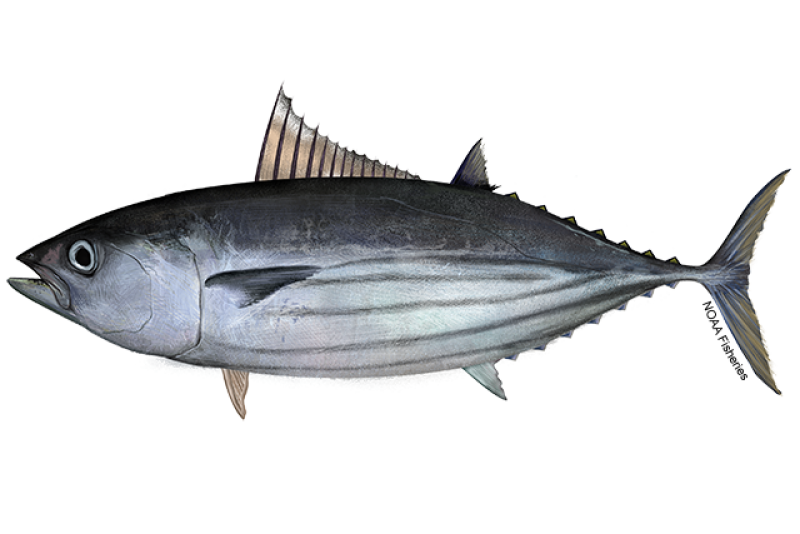

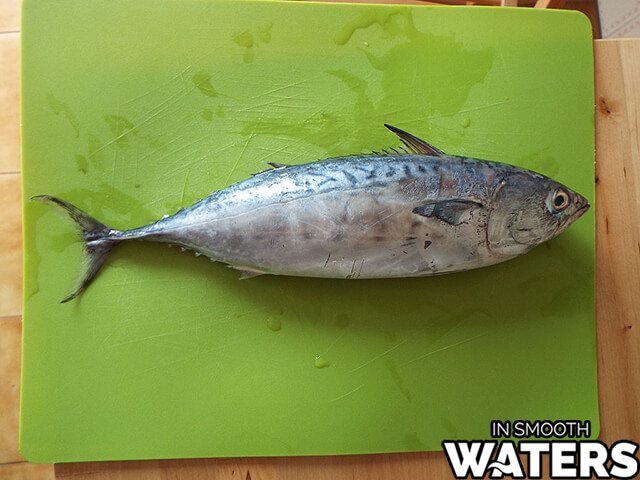

Bluefin Tuna

Habitat: Open waters of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans Distance covered each year: Approximately 10,000 miles

Bluefin tuna is one of the largest tuna species and can grow to lengths of over 10 feet and a weight of over 1,000 pounds.

The bluefin tuna is a highly migratory marine species and travels long distances in search of food and suitable spawning grounds. They swim between the Western Pacific and Eastern Pacific several times a year. Besides, they are fast swimmers, swimming at 43 miles per hour.

Unfortunately, Bluefin tuna is a popular target for commercial and recreational fishermen. This is because of the high price of the meat used to prepare sushi and sashimi.

Leatherback Turtles

Habitat: All oceans except the Arctic and Antarctic Distance covered each year: 12,000 miles

Another highly migratory marine species is the leatherback turtle. The leatherback turtle is a reptile and the largest of all sea turtles. They can grow to lengths of up to 5 feet and weigh up to 1,000 pounds.

Interestingly, they are the only turtles that do not have a hard shell but instead have a leathery carapace. These turtles occur in all oceans except in the Arctic and Antarctic.

Leatherback turtles migrate long distances yearly, swimming over 12,000 miles between their nesting and feeding grounds. They are also highly skilled divers, with a record of almost 4000 feet, thus diving more profoundly than any marine mammal.

Leatherbacks need to eat a lot of jellyfish to survive, and the abundance of jellyfish varies depending on the season and location. Therefore, by migrating, leatherbacks ensure they have enough food throughout the year.

However, migration is a dangerous journey for them. They face many threats, such as bycatch, being eaten by predators, and worse still, their eggs are harvested for human consumption. Sadly, due to these dangers, their population is declining at an alarming rate.

Blue Marlin

Habitat: Occur across tropical and subtropical waters of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans Distance covered each year: Over 12,000 miles

The blue marlin is another highly migratory fish. They are pelagic species and mainly occur in warm tropical waters. It is the largest marlin species growing up to 14 feet in length and about 2000 pounds in weight. Amusingly, females are usually larger than males.

Every year, they swim from their breeding grounds in the tropical waters of the Indian and Pacific oceans to the colder waters of the Atlantic. The fish travel in schools, often numbering in thousands, and cover vast distances of up to 12,000 miles.

Unfortunately, this migratory behavior exposes the blue marlin to several threats, such as overfishing, bycatch, and climate change . Worse, it is currently among the endangered species listed by the ICUN.

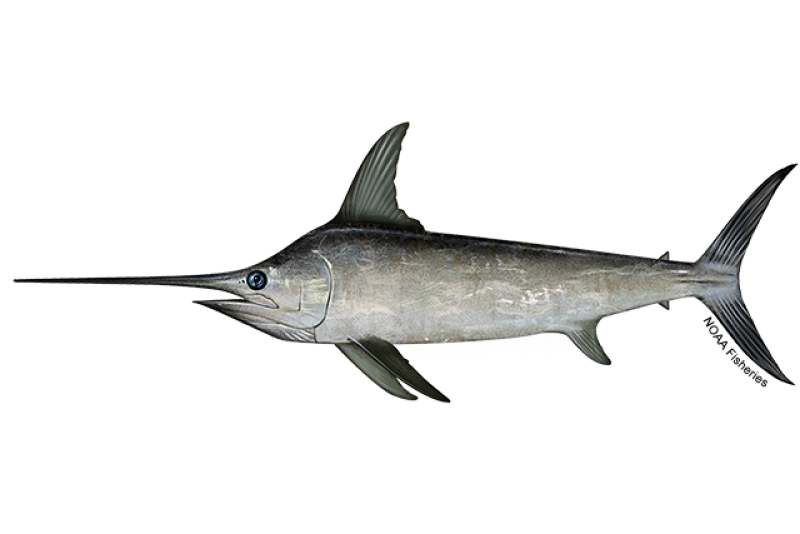

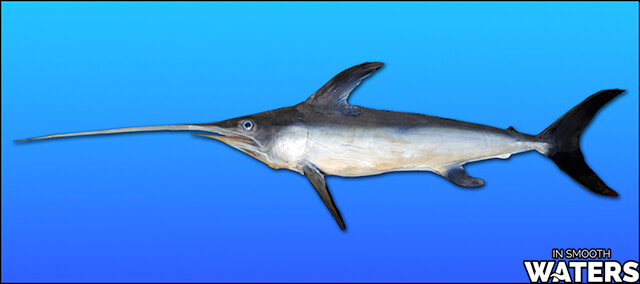

Habitat: Live in tropical and temperate waters Distance covered each year: 3,000 miles

Swordfish are also among the highly migratory marine species. They occur in tropical and temperate waters. They can grow up to 15 feet long and weigh up to 1000 pounds.

They travel long distances yearly for food and suitable breeding grounds, often covering about 3000 miles. They are also fast swimmers, swimming 60 miles per hour. But unlike many fish, swordfish are solo swimmers, meaning they do not swim in schools.

Currently, there has been a decline in the global swordfish population. This is primarily due to overfishing, bycatch, and climate change.

Habitat: Live in all oceans of the world Distance covered each year: 18,000 miles

Adding to our list is the blue whale . The blue whale is a marine mammal believed to be the largest animal ever. They live in every ocean and mainly prefer upwelling cold waters. They can grow up to 98 meters long and weigh up to 1500 pounds.

It is a highly migratory marine species that migrate seasonally between different areas in search of food and mating opportunities—swimming up to 18,000 miles. Their main migration routes are between their Antarctic breeding grounds and Arctic feeding grounds. However, some blue whales also migrate between the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Blue whales are often seen alone or in small groups of 2-3 animals. These groups usually consist of a mother and her calves. Unfortunately, blue whales are also among the most endangered species. During their migration, they face threats such as climate change, bycatch, and being hit by ships, among others.

Great White Shark

Habitat: Live in the coastal waters of North America, South Africa, and Australia Distance covered each year: Approximately 2,500 miles

White sharks, also known as great white sharks , are one of the most aggressive predators in the ocean. Although they occur in all oceans of the world, they mostly live in the coastal waters of North America, South Africa, and Australia.

They are mostly grey or blue-grey, with a white belly. They also have torpedo-shaped bodies and large, triangular dorsal fins. White sharks can grow up to lengths of 20 feet and can weigh over 5,000 pounds.

They are highly migratory marine species, swimming almost 2,500 miles from their breeding grounds in North America to their feeding grounds in South Africa and back again yearly.

While white sharks are not considered endangered, their numbers are declining. This is mainly due to the illegal hunting of these animals for their fins and teeth. In addition, they are also accidentally caught by fishermen who are targeting other species.

Habitat: Live in the cold, clear waters of the Northern Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Mainly in coastal areas and near freshwater rivers where they can spawn Distance covered each year: Over 1,000 miles

Salmon are highly migratory marine species living in fresh and saltwater environments. They are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It is a popular food fish that is high in omega-3 fatty acids, can grow up to lengths of 5 feet, and can weigh over 100 pounds.

Typically, salmon are anadromous, and migration is essential to their lifecycle. Therefore, they breed in freshwater, and as they mature, they move to the ocean, where they spend most of their life, then migrate back to freshwater to reproduce.

Amusingly, Folklore tracking studies show that salmon fish return to the same spot where they hatched to spawn. However, some stray and spawn in different freshwater systems.

Unfortunately, in recent years, salmon populations have been declining. This is due to overfishing and habitat loss. Climate change is also playing a role in their decline, as warmer water temperatures and changes in the timing of river flows impact salmon migration.

Why is migration important to marine animals?

Migration is important to marine species for reasons such as looking for food and mating. What’s more, migration also helps these species escape from predators and enable them to adapt to different environmental conditions.

What are the benefits of highly migratory marine species?

Highly migratory marine species have many benefits. First, they are a significant food source for thousands of people worldwide. Secondly, they are crucial to the economy and livelihoods of many coastal communities. What’s more, they help keep ecosystems in balance by redistributing nutrients and energy.

What challenges do marine species face while migrating?

There are many challenges that marine species face during migration. These challenges include overfishing, bycatch, and being hit by ships. On top of that, another challenge is climate change. With changes in water temperature, their migration patterns are affected.

How do marine animals migrate?

Some marine animals migrate by swimming long distances in open waters, while others use currents to travel large distances with little effort. Besides, some migrate vertically in the water column, while other species migrate to different areas during different times of the year.

About Ocean Info

At Ocean Info, we dive deep into ocean-related topics such as sealife, exploration of the sea, rivers, areas of geographical importance, sailing, and more.

We achieve this by having the best team create content - this ranges from marine experts, trained scuba divers, marine-related enthusiasts, and more.

Dive into more, the ocean is more than just a surface view

Tombolo vs Sandbar

Although both tombolos and sandbars are natural developments that form in much the same way, there are key differences that set the two apart, both from a physical perspective and how they tie into the life of the marine species that they support.

5 Main Types of Algae in the Ocean

Coral Color: Pigments of The Vibrant Ocean

Adam’s Bridge: A Natural Wonder or a Man-Made Masterpiece?

Ocean Info is a website dedicated to spreading awareness about the ocean and exploring the depths of what covers two-thirds of Earth.

[email protected]

About Us Charity Contact Privacy Policy

Ocean Animals and Plants Exploration Comparisons Listicles Lakes

Save The Planet

Ocean Info © 2024 | All Rights Reserved

The deep blue sea is more amazing than you think...

Discover 5 Hidden Truths about the Ocean

27 Fish that Migrate (A to Z List with Pictures)

Examples of fish that migrate include alewives, American paddlefish, Atlantic cod, Atlantic salmon, and beluga sturgeon.

Migrating fish swim thousands of miles in search of food, spawning grounds, and better living conditions due to seasonal changes. Some species, like salmon, even travel upriver to lay their eggs.

Let’s take a look at some examples of fish that migrate and why they do it.

Examples of Fish that Migrate

1. alewives.

These small, silvery fish migrate in large schools in late spring from the ocean into estuaries and rivers to spawn.

Related Article: 13 Fish that Look Like Dragons

2. American Paddlefish

The American paddlefish is a freshwater fish that is native to North America. It can grow to be over six feet long and weigh over 200 pounds. The American paddlefish migrates in search of food. plankton, which it feeds on, is more abundant in certain areas at different times of the year.

3. Atlantic Cod

The Atlantic cod is a migratory fish that swims in the ocean waters off the coast of North America. Every year, they migrate south to escape the cold weather and find better feeding grounds. In the spring, they return to their northern homes to spawn.

4. Atlantic Salmon

Atlantic salmon are born in freshwater rivers, but they spend most of their lives in the ocean. Around the time they reach sexual maturity, typically after 3-5 years, they return to their natal river to spawn. After spawning, they die.

The journey back to their natal river can be thousands of miles long and is fraught with danger, including predators, parasites, and disease. But the urge to reproduce is strong, and salmon will risk everything to make it back to their birthplace to lay their eggs.

5. Beluga Sturgeon

The Beluga Sturgeon is a large, white fish that can grow up to 20 feet long and weigh over 2,000 pounds. They are found in the cold waters of the Arctic Ocean and migrate to the warmer waters of the Caspian Sea to spawn.

6. Black Sea Salmon

The Black Sea salmon is a species of migratory fish that is found in the Black Sea and the adjacent rivers. Salmon migrate in order to breed and lay their eggs in freshwater rivers. After hatching, the young salmon spend several months in freshwater before migrating to the sea where they spend the majority of their lives.

7. Blue Cod

Found in the waters around New Zealand, blue cod migrate in search of food. Their diet consists mainly of small invertebrates, so they move to areas where these creatures are abundant.

8. Chinook Salmon

The Chinook salmon is the largest species of Pacific salmon. They can grow up to four feet long and weigh over 60 pounds. Every year, Chinook salmon migrate from the ocean upriver to lay their eggs in freshwater streams. After hatching, the young salmon spend a few years in freshwater before migrating back to the ocean to live out the rest of their lives. The Chinook salmon’s annual migration can be over 3,000 km long.

9. Chum Salmon

Chum salmon are found in the northern Pacific Ocean and migrate to spawn in rivers in Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington. Every fall, chum salmon leave the ocean and swim upriver to lay their eggs in freshwater gravel beds.

10. Coho Salmon

Every fall, coho salmon migrate from the Pacific Ocean back to their freshwater birthplace to spawn. The journey can be over 1,000 miles long and requires them to swim upstream through rivers and creeks.

11. European Eel

The European eel is a long, snake-like fish that can be found in rivers and lakes all across Europe. Every year, millions of eels migrate from their homes in freshwater to the Atlantic Ocean to mate and lay eggs.

12. European Sea Sturgeon

These fish can grow up to 20 feet long and live in the Atlantic Ocean. Every spring, they migrate from the Mediterranean Sea into the Black Sea to spawn.

13. Green Sturgeon

The green sturgeon is a large fish that can live up to 60 years. It is found in the Pacific Ocean from Alaska to central California. Every year, adult green sturgeons migrate upstream to spawn in rivers. After spawning, they return to the ocean.

14. Hawaiian Freshwater Goby

The Hawaiian freshwater goby is a small fish that is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. It is found in streams and rivers on all of the main islands, except for Kahoʻolawe.

These fish migrate in search of food and better living conditions. During the wet season, the gobies move to higher elevations in search of food. As the water level lowers in the dry season, the fish move to lower elevations where there is more water.

15. Herring

Herring migrate in large schools, sometimes consisting of millions of fish. They travel to find food or to escape predators. Herring have a special sense called lateral line which allows them to sense movement in the water around them. This sense helps them stay together in large groups while they are migrating.

16. Lake Sturgeon

These giant freshwater fish can grow up to 7 feet long and live for over 100 years! They are bottom-feeders and eat things like insects, crayfish, and small fish.

Every spring, sturgeon migrate upstream to lay their eggs in rivers and streams. After spawning, they head back downstream to the lakes where they spend the rest of the year.

17. Mekong Giant Catfish

The Mekong giant catfish lives in the Mekong River in Southeast Asia. It can grow to be over 10 feet long and weigh up to 660 pounds. The fish is endangered and is only found in this one river.

During the dry season, the water level in the Mekong River drops significantly. This forces the fish to migrate to deeper waters in order to find food and avoid being stranded on land.

18. North American Eel

Eels are a type of fish that spend most of their lives in freshwater rivers and lakes, but they must return to the ocean to spawn.

Some eels travel as far as 3,700 miles from North America to the Sargasso Sea in order to mate and lay their eggs.

19. Red Tuna

Red tuna migrate to different areas in search of food. As the water temperatures change, so does the location of their prey. In order to follow their food source, red tuna must migrate to where the food is plentiful.

20. Russian Sturgeon

The Russian sturgeon is a species of fish that is found in the Black and Caspian seas. They can grow to be up to six feet long and weigh over 200 pounds. These fish migrate in order to spawn. They travel from the Black sea into the River Danube where they lay their eggs.

These fish travel up the Chesapeake Bay to spawn in the spring. They follow the same path every year, moving from the Atlantic Ocean into freshwater rivers and streams.

22. Shortnose Sturgeon

The shortnose sturgeon is a threatened species of fish that can be found in the eastern United States. Every year, they migrate up the Hudson River to spawn in the spring. They travel back down the river in the fall.

23. Siberian Sturgeon

The Siberian sturgeon is a type of fish that is found in the rivers and lakes of Siberia. Every year, these fish migrate upstream to lay their eggs in the shallow waters near the shore. The journey can be as long as 1,000 miles.

One reason why the Siberian sturgeon migrate is to avoid the cold winters in Siberia. The water temperatures in the rivers and lakes can drop to below freezing, and the sturgeon need to migrate to warmer waters to survive.

24. Sockeye Salmon

Sockeye salmon are anadromous fish, meaning they live in the ocean but return to freshwater to spawn. Every year, sockeye salmon migrate from the ocean back to their natal streams in Alaska and British Columbia. The journey can be over 2,000 miles long and is one of the longest migrations of any vertebrate animal.

25. Steelhead Trout

Steelhead trout are a type of salmon that is found in the Pacific Ocean. Every year, they migrate upriver to lay their eggs. The journey can be up to 3,000 miles long.

Steelhead trout migrate in order to find the best possible spawning grounds. Since they lay their eggs in rivers, they need to find stretches of river that are clean and have a good water supply. They also need to find areas where there are lots of other steelhead trout so that their eggs will have a good chance of surviving.

26. White Sturgeon

The white sturgeon is a freshwater fish that can grow to be up to 20 feet long and weigh over 1,000 pounds. They are found in rivers and lakes all across North America, from Alaska all the way down to California.

Every year, between late fall and early winter, the white sturgeon migrate upstream to spawn in the shallower waters of rivers and streams. After spawning, they return back downstream to the deeper waters where they spend the rest of the year.

27. White Tuna

White tuna are found in all oceans, but they migrate to different areas at different times of year. In the spring and summer, they move to cooler waters near the poles. In the fall and winter, they move to warmer waters near the equator. They do this to follow their food source – small fish that are also migrating.

There are many different types of fish that migrate. Some migrate to breed, some to find food, and others to escape predators. Migration can be a difficult journey, and many fish don’t survive the trip. But for those that do, migration provides an important way to keep populations healthy and ensure the continuation of their species.

Hi, I’m Garreth. Living in South Africa I’ve had the pleasure of seeing most of these animals up close and personal. When I was younger I always wanted to be a game ranger but unfortunately, life happens and now at least I get to write about them and tell you my experiences.

Advertisement

The Fastest Fish in the Ocean Can Swim at Nearly 70 MPH

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

While there are tons of fish in the sea, only a few hold the title of the fastest fish in the ocean. You might wonder how the fastest fish swim at such high speeds.

The key to a fish's speed is a streamlined shape. It's usually fish with a pointed snout and broad, propulsive tail that are able to move through the open with minimal resistance.

So, which fish are the fastest? Let's take a look!

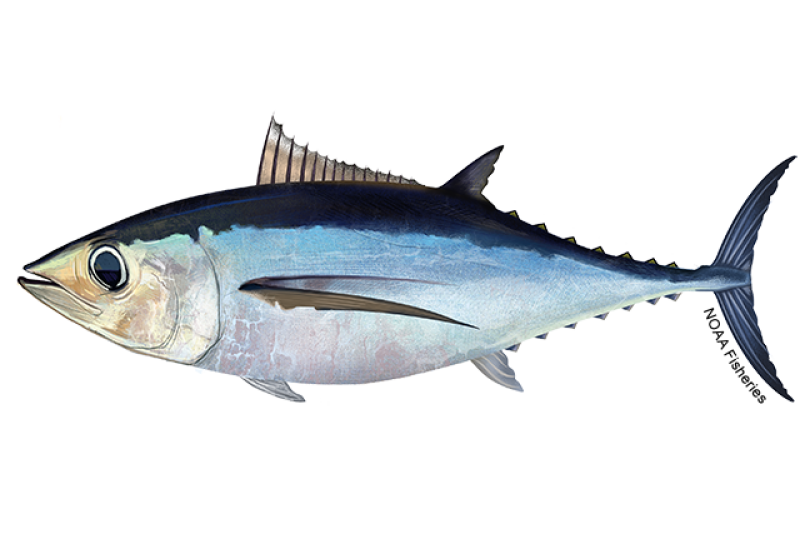

- Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

- Striped Marlin

- Black Marlin

- Fourwing Flying Fish

1. Sailfish

The sailfish stands out as the fastest fish in the world, a title it proudly holds thanks to its remarkable adaptations and evolutionary prowess. In fact, the sailfish can reach top speeds of 68 mph (110 km/h).

Inhabiting the warm waters of the Indian and Pacific oceans, the sailfish features a streamlined shape that epitomizes hydrodynamic efficiency. Its powerful muscles that contract rapidly, propelling it through the water at velocities that top out during short periods of high-speed pursuit.

Fins Fit for Speedy Evasion

What really sets the species apart from other fish are its numerous fins arrayed with precision along its sleek body. The sail-like dorsal fin, from which it derives its name, along with dorsal fins projecting from the back and pectoral fins on the sides, play a crucial role in maneuverability and stability.

Meanwhile, the tail fin and anal fins provide the forward propulsion needed to reach top speeds.

Beneath its sleek exterior, bony spines add to its structural integrity, allowing for bursts of speed that captivate and intrigue marine biologists and enthusiasts alike.

These aquatic speedsters have an alternate use for their sail-like dorsal fin. While it helps them cut through water with minimal resistance, they also sometimes raise it to intimidate predators. Nature loves a multi-tool.

2. Swordfish

Diving deeper into the ocean, the swordfish emerges as another one of the fastest fish out there. The maximum speed of a swordfish is about 60 mph (94 km/h).

Known for its iconic elongated bill, resembling a sword, this species cuts through the water with precision and agility. The swordfish's large, powerful muscles enable quick bursts that propel the fish forward, allowing it to navigate through the water at speeds that leave observers in awe.

Swordfish can withstand particularly cold water temperatures because of a specialized organ located near their brain, known as a countercurrent heat exchange mechanism.

This special organ literally heats their brain and eyes, allowing them to think clearly in colder waters. It also helps them effectively see and hunt their prey.

In tropical and subtropical waters around the world, the wahoo is a name that evokes with speed and agility. This striking fish is celebrated for its ability to reach speeds that make it a formidable predator and a sought-after prize among sport fishermen. The maximum speed for a wahoo is about 48 mph (77 km/h).

The wahoo's slender, torpedo-shaped body is perfectly adapted for high-speed pursuits, allowing it to dart through the water with incredible acceleration. Its streamlined form minimizes drag, enabling the wahoo to slice through the ocean currents as it chases down its prey with ruthless efficiency.

One fascinating feature of the wahoo is its series of sharp, serrated teeth , capable of slicing through its catch (typically smaller fish and squid) with ease.

4. Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

Among the giants of the sea, the Atlantic bluefin tuna commands attention not only for its size but also for its ability to swim faster than many of its oceanic counterparts. In fact, it's the fastest tuna in the world, reaching top speeds of 44 mph (70 km/h).

This species combines brute strength with a hydrodynamic silhouette, and its muscular body is supported by a series of finlets on the dorsal and ventral sides, reducing drag and allowing for swift, efficient movement.

An intriguing aspect of the bluefin tuna is that they must keep swimming in order to get enough oxygen from the water. Like some shark species, Atlantic bluefin tuna must keep swimming forward with their mouth opens to keep their blood oxygenated; they don't have the ability while they're stopped.

Additionally, Atlantic bluefin tunas have a countercurrent exchanger that allows them to regulate body temperature in cooler waters. This allows them to hunt efficiently in cold water, much like swordfish.

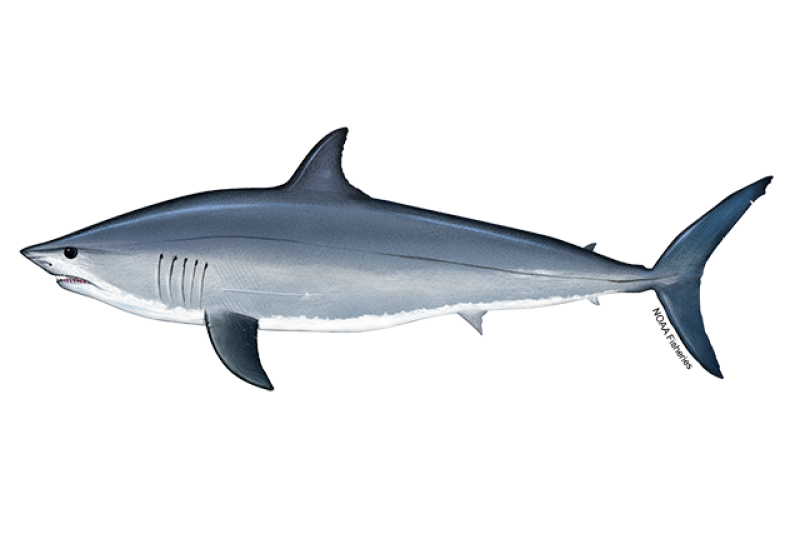

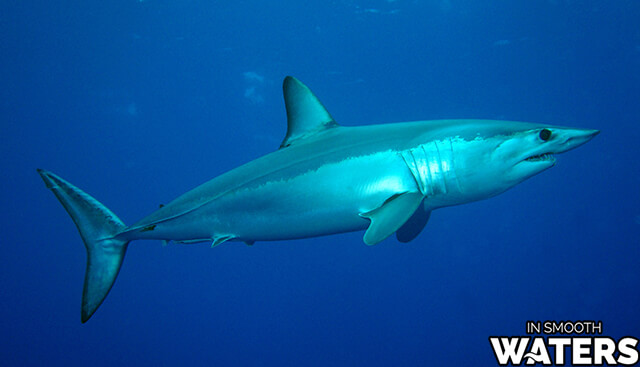

5. Mako Shark

The mako shark, found in tropical and temperate waters around the world, is the fastest known species of shark, reaching a maximum speed of 46 mph (74 km/h).

The mako's sleek, streamlined body allows it to chase down swift prey, with its powerful caudal fin, shaped like a crescent moon, acting as a propulsive force. The endothermic system of this species also allows it to maintain a body temperature higher than the surrounding water.

Like the bluefin tuna, the mako shark must keep swimming in order to live. It needs water to constantly pass through its gills to create oxygen for in order to breathe. If make sharks stop swimming, they won't survive.

Additionally, mako sharks can remarkably see in the dark . Unlike many other sharks who rely on electroreception to navigate, the mako uses their smell, hearing and vision. These sharks have light-detecting cells and a tapetum lucidum (like cats!) that helps them to see in the dark. This trait combined with their strong sense of touch, allows them to sense tiny pressure changes and movements in the water.

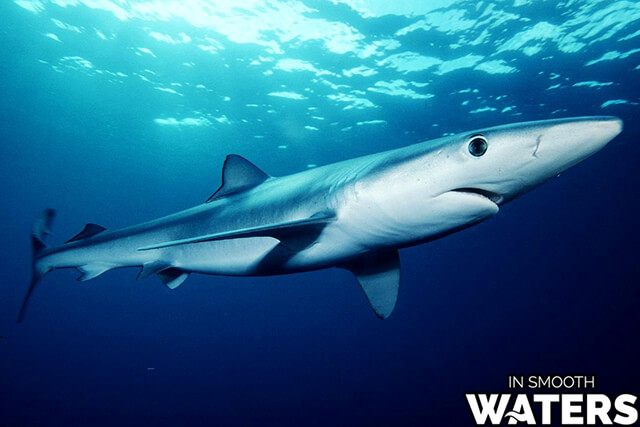

6. Blue Shark

Gliding through the deep waters of temperate and tropical oceans (the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic ocean), this species can reach a maximum speed of 43 mph (69 km/h). Their speed and stamina allow them to traverse vast distances in their quest for food and mating grounds.

These slender, indigo-colored predators are designed for endurance and speed, with long, lithe bodies that cut through the water with minimal resistance.

Their elongated pectoral fins enable them to maintain stability and maneuver with precision, while their powerful tails provide the propulsion necessary for sudden bursts of speed.

Blue sharks' migratory patterns , which are among the longest in the shark world, reflect their search for food and warm waters. Blue sharks have been known to travel across entire ocean basins, a testament to their stamina, adaptability and efficiency.

7. Bonefish

In the shallow, clear waters where the ocean meets the land, the bonefish emerges as a silent sprinter, known for its ability to reach speeds of 40 mph (64 km/h).

The bonefish's torpedo-shaped body and large, powerful tail fin work in unison to propel it forward with bursts of speed, enabling it to escape predators and navigate through its complex, reef-studded habitats with ease.

Bonefish are capable of surviving in shallow, brackish backwaters because they have a special, lung-like air bladder. Essentially, bonefish can suck in air and then hold onto it, allowing them to breathe comfortably in low-oxygen waters.

You'll likely find them moving with the tide, taking advantage of deep water and increased oxygen at low tide and in the shallower flats during high tide where they can hunt for their food.

8. Striped Marlin

Navigating the tropical and temperate regions of the Indo-Pacific Ocean is the striped marlin. Recognized for its striking appearance and formidable speed (with top speeds reaching 50 mph (80 km/h)), the striped marlin is a creature of beauty and power.

Its sleek, streamlined body — equipped with a distinctive bill and pronounced dorsal fin — combines with a flexible spine, allowing it to propel itself forward at high speeds, making it one of the ocean's most efficient predators.

The striped marlin uses its sharp bill to stun prey, a technique that showcases its intelligence and adaptability. While you might think it would impale its victims, it actually stuns them by slashing sideways .

The marlin's speed, combined with this hunting strategy, makes it a master of the marine environment, capable of capturing a wide variety of prey.

9. Black Marlin

Though experts believe the black marlin's swimming speed is around 30 mph (40 km/h), they are capable of reaching much higher speeds in short bursts. The BBC even recorded one reaching 80 mph (128 km/h)!

This impressive species, with its robust, cylindrical body and spear-like upper jaw, is engineered for speed. The black marlin's powerful tail fin, split into two crescents, acts as a propulsive force. Its sleek physique minimizes drag, allowing the black marlin to dash through the water with remarkable efficiency.

This fish has a reputation as one of the most sought-after game fish. Sport anglers from around the world dream of hooking a black marlin, not just for the thrill of the catch but also for the respect earned from battling such a swift and formidable opponent.

10. Fourwing Flying Fish

Soaring above the surface of subtropical waters of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, the fourwing flying fish represents hits top speeds of 37 mph (60 km/h) .

This species has evolved not just to swim but to glide over the water, using its uniquely developed pectoral and pelvic fins as wings.

These "four wings" enable the fish to escape predators by making powerful leaps out of the water, propelling themselves through the air at considerable speeds. The streamlined body of the fourwing flying fish reduces drag both in water and air, reaching impressive heights of nearly 4 feet (2 meters).

It can also glide for very long distances, typically up to 650 feet (200 meters). That said, records have shown that they're able to make consecutive glides of up to 1300 feet (400m).

11. Barracuda

Lurking in the shadows of coral reefs and seagrasses, the barracuda is an intimidating presence in the marine world, known for its sharp snouts and the ability to reach speeds of 36 mph (58 km/h) in short bursts.

With a sleek, streamlined body and a robust tail fin, the barracuda is built for rapid acceleration, allowing it to ambush prey. Its elongated body is perfectly adapted for slicing through the water with minimal resistance, and its large, pointed teeth are ideal for seizing and holding onto slippery fish.

That said, barracudas are curious and often misunderstood nature. Despite their fearsome reputation, they are usually not a threat to humans unless provoked.

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a HowStuffWorks editor.

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

Internet Explorer lacks support for the features of this website. For the best experience, please use a modern browser such as Chrome, Firefox, or Edge.

Highly Migratory Species

Highly migratory fish travel long distances and often cross domestic and international boundaries. These pelagic species live in the water of the open ocean, although they may spend part of their life cycle in nearshore waters. Highly migratory species managed by NOAA Fisheries include tunas, some sharks, swordfish, billfish, and other highly sought-after fish such as Pacific mahi mahi.

These h ighly migratory species are targeted by U.S. commercial and recreational fishermen and by foreign fishing fleets. Because they migrate long distances and live primarily in the open ocean, only a small fraction of the total harvest of these species is taken within U.S. waters.

In the United States, NOAA Fisheries sustainably manages highly migratory species under the Magnuson-Stevens Act in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans:

- Atlantic Highly Migratory Species (including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean)

- West Coast Highly Migratory Species

Responsible management also requires international cooperation through a number of agreements and regional fishery management organizations (or RFMOs) including the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission , International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna , Commission on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, and Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora .

More Information

- Sustainable Fisheries

- International Affairs

- Commercial Fishing

- Recreational Fishing

- HMS Fishing Permits

Species News

NOAA Partners to Remove Kellogg Dam, Providing Passage for Threatened Chinook, Coho, and Steelhead

Necropsy Offers Rare Opportunity to Study White Shark Biology

Cold Water Connection Campaign Reopens Rivers for Olympic Peninsula Salmon and Steelhead

10 Projects Will Support Urban Fish Restoration around Portland, Oregon

2024 Bottom Trawl Survey in Photos

A Look at the Vast Waters and Rich Diversity of Marine Life in the U.S. Pacific Islands

Collecting Data on Diverse West Coast Waters

Top 5 Shark Videos and More

Dolphinfish management strategy evaluation in the u.s. atlantic.

NOAA Fisheries is designing a new management approach for dolphinfish, also known as mahi mahi. We are working with fishing communities to maximize the benefits of this fishery management approach across multiple user groups and regions.

Celebrating Reliable Shark Tagging Citizen Scientists

Meet some of the people who exemplify what it means to be a reliable tagger for NOAA’s Cooperative Shark Tagging Program.

Commercial Fishing Business Cost Survey

Our survey seeks to better understand the costs associated with commercial fishing in the Northeast.

Fisheries Ecology in the Northeast

We study the relationship between marine life and their environment to support sustainable wild and farmed fisheries on the Northeast shelf, creating opportunities and benefits for the economy and ecosystem.

International Collaboration

Fish and other marine animals travel beyond national boundaries.

Atlantic Bigeye Tuna

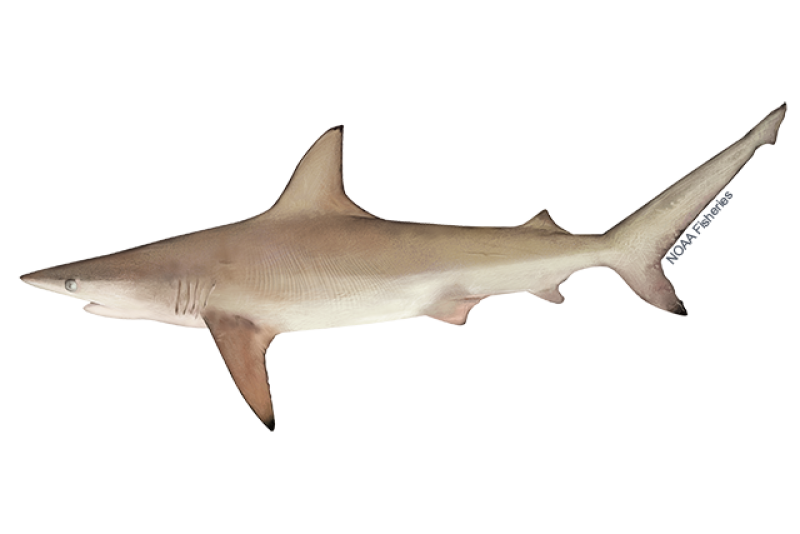

Atlantic Blacktip Shark

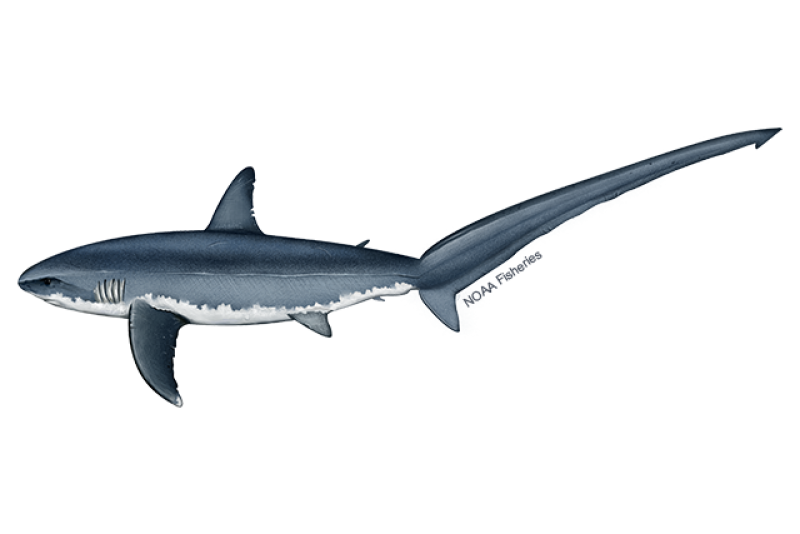

Atlantic Common Thresher Shark

Atlantic Sharpnose Shark

Atlantic Shortfin Mako Shark

Atlantic Skipjack Tuna

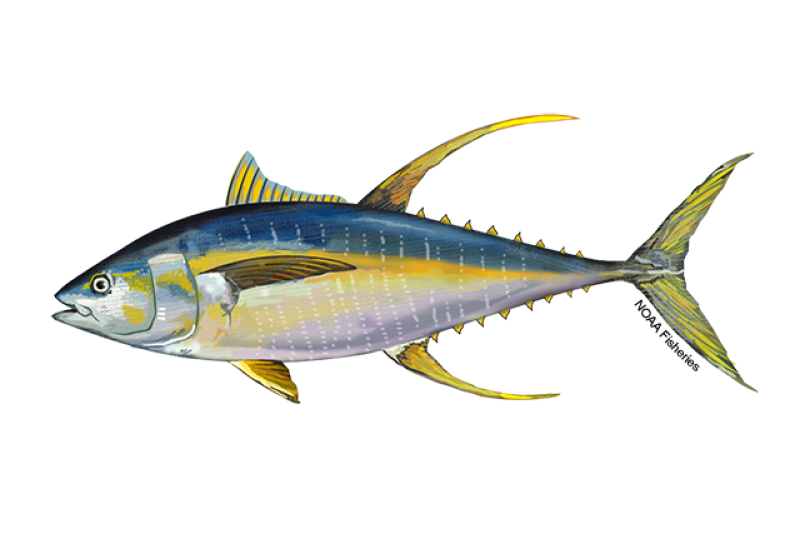

Atlantic Yellowfin Tuna

North Atlantic Albacore Tuna

North Atlantic Swordfish

North pacific swordfish.

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

Pacific albacore tuna.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

'Really amazing': scientists show that fish migrate through the deep oceans

Analysis of underwater photographs has demonstrated what marine biologists have long suspected – seasonal fish migrations

New research has finally demonstrated what many marine biologists suspected but had never before seen: fish migrating through the deep sea.

The study, published this month in the Journal of Animal Ecology , used analysis of deep-sea photographs to show a regular increase in the number of fish in particular months, suggesting seasonal migrations.

Tracking fish in the deep sea is challenging. They are sparsely distributed, the water is nearly devoid of sunlight, and the monitoring equipment has to withstand enormous pressure.

The study used photographs taken by the Deep-ocean Environmental Long-term Observatory System (Delos) , two observatories on the sea bed 1,400m below the surface, off the coast of Angola. The researchers analysed 12,703 photographs – only 502 of which had actually managed to capture a fish – taken over seven-and-a-half years, and found that each year, in late November and June, there was a spike in the number of fish.

“It is certainly not unprecedented but it has never really been demonstrated,” says Rosanna Milligan , an assistant professor at Nova Southeastern University in Florida and the lead author on the paper. “That is what we were able to do with this study.”

“Even after all these years, one of my favourite parts of being a scientist is when you do those first graphs of your results and start to see something emerging from the data,” says David Bailey , a senior lecturer at the University of Glasgow and a co-author on the paper. “That’s one of the greatest thrills of the whole scientific endeavour. It was really, really amazing.”

Even with this new discovery, Milligan and Bailey still say there is a lot they don’t know.

“The natural thing to do is to find out where the fish are coming from and going to when they move around,” says Bailey. “What is going on? What does it mean and what are the fish doing?”

Very little is known about the behaviour of any of the fish photographed. Grenadiers, a family of fish seen in more than 100 of the Delos photos, have long tails that may allow them to move great distances at low speed – but despite being a relatively common deep-sea fish, little information exists on how far they can swim. A 1992 paper , for instance, put acoustic tracking devices in bait and fed them to grenadiers, but the devices only tracked the fish up to 1km away.

Milligan thinks the fish might be migrating to follow dying organisms on the surface. Plankton blooms off the coast of west Africa every year four months before the deep-sea fish migrate into the area. Given that the deep sea is dependent on life at the surface that dies and sinks to the bottom, it is possible that other animals could be gathering to take advantage of the dying plankton, and the deep-sea fish migrate to eat those.

“We just have no idea how these things act,” says Tim O’Hara , a researcher and senior curator of marine zoology at Museums Victoria, Australia, who was not involved in the research. “We are literally groping in the dark. It’s kilometres down in the ocean and we get these tiny bits of information from one or two locations and we’re trying to put together a big picture.”

Milligan and Bailey hope this discovery encourages other researchers to look for similar patterns in the deep oceans.

“Maybe if we had more of this level of surveillance in other places, we would find fish migrations in all kinds of places,” says Bailey. “It’s just that [Angola] is where we happened to be observing in this level of detail for this amount of time … This could be happening all over the place.”

- Marine life

- Seascape: the state of our oceans

Most viewed

Smithsonian Ocean

The great pacific migration of bluefin tuna.

Shortly after their first birthday, Pacific bluefin tuna ( Thunnus orientalis ) complete an impressive feat. From the spawning grounds in the Sea of Japan where they were born, the young tuna embark on a journey over 5,000 miles (8,000 km) long, across the entire Pacific Ocean to the California coast where they spend several years feeding and growing. Until recently, scientists believed only a small portion of juvenile tuna made the journey, but several new studies show that may not be the case—in some years the majority of tuna aged between one and three participate in the trans-Pacific migration.

To get to California, the fish traverse through icy, Arctic waters that sometimes reach temperatures close to 9 degrees Celsius (about 16 degrees Fahrenheit). That’s pretty chilly, even for a fish. But like the closely related Atlantic and southern bluefin, Pacific bluefin tuna have a few special adaptations to help them navigate through the cold water. As one of the few warm-blooded (or endothermic) fish, bluefin tuna retain the heat they produce as they swim. Most fish lose a lot of their body heat as the warm blood circulates through the gills. The thin capillary walls in the gills are perfect for the blood to pick up oxygen, but they also leave the blood exposed to the icy temperatures of the water. For a bluefin, that’s not a problem. Their specialized blood vessel network, also known as a counter-current heat exchange system, aligns the warm veins leaving the muscles right next to the cooler, incoming arteries so that the heat is passed from the veins to the arteries in an efficient loop. The heat stays in the muscle and never gets the chance to be sapped away in the gills.

Once the young tuna reach the shores of California they will remain there for several years, traveling up and down the coast between Mexico and sometimes as far north as Washington State. By the time the tuna reach age seven many return to the Western Pacific to spawn off the coast of Japan.

This migration is a pretty amazing feat, but the Pacific bluefin tuna population is seriously struggling. It may seem like a minor detail, but the fact that more tuna make the trans-Pacific migration than previously thought has huge implications for managing the fishery. A high demand for tuna to supply the sashimi industry means there is extraordinary fishing pressure on the species. Sushi chefs and restaurant owners pay significant money for the fresh fish—at the famous Tsukiji market in Tokyo, a single tuna was sold for 1.8 million dollars in 2013. Although buying at such an outrageous price is more of a marketing scheme to attract new bluefin-eating restaurant customers than a true representation of demand, there is little doubt that the appetite for tuna has taken its toll. Scientists from the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species (ISC) estimated in a 2016 report that only 2.6 percent of the original, pre-fished population remains, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates the population is 25 percent of what it was in the 1950s when the first population data was recorded.

If a high number of Pacific bluefin live their early lives off the coast of California, any catch limits enforced by the United States and Mexico will also impact how many tuna live long enough to swim back to Japan to spawn. Tuna caught by fishermen in the Eastern Pacific, on the West Coast of North America, will never have the chance to reproduce and help the population rebound.

Currently, a serious debate on whether to list the Pacific bluefin tuna as an endangered species, rather than the current threatened designation, is underway. And there is a glimmer of hope for the species—in September 2017 international leaders from countries that fish the tuna agreed to a goal of reaching 20 percent of the Pacific bluefin’s historic population by 2034.

So, the next time you are tempted to order a tuna sushi roll, think of its herculean effort to swim across an entire ocean and the challenges these fish face to survive. Currently, the Monterey Seafood Guide and Marine Conservation Society FISHONLINE recommend avoiding all Bluefin tuna—the Albacore tuna is a better choice. Perhaps, a little time and space are just what the Bluefin need and our decision to let them be is the key to their survival.

- Make Way for Whales

- Sharks & Rays

- Invertebrates

- Plants & Algae

- Coral Reefs

- Coasts & Shallow Water

- Census of Marine Life

- Tides & Currents

- Waves, Storms & Tsunamis

- The Seafloor

- Temperature & Chemistry

- Ancient Seas

- Extinctions

- The Anthropocene

- Habitat Destruction

- Invasive Species

- Acidification

- Climate Change

- Gulf Oil Spill

- Solutions & Success Stories

- Get Involved

- Books, Film & The Arts

- Exploration

- History & Cultures

- At The Museum

Search Smithsonian Ocean

Ranking the 10 Fastest Sea Animals in the Ocean

The ocean is filled with amazing creatures, and some of them are incredibly fast. Imagine this: water is much thicker than air, so moving quickly through it is an incredibly tough job.

Even though this is true, many sea animals swim through water at incredible speeds. In fact, some are comparable to how fast a cheetah runs across land. It makes you wonder, how do they do this?

This article will explore the top 10 fastest animals in the ocean. From the quick Bonito to the super-fast Black Marlin, we’ll see how these creatures are adapted to zoom through the water. Let’s begin!

Quick Overview

Top 10 fastest sea animals.

Here’s a fun tidbit: swimming a certain distance uses four times more energy than running the same distance (at least for humans). That’s because water is thicker than air and creates more resistance.

So, when sea animals swim, it’s like us walking through a packed crowd — it’s tough since they’re pushing against the heavy water around them. How do they manage that, and which are the fastest swimmers? Let’s find out.

10. Bonito (40 mph)

Ranking 10th among the fastest sea animals, the Bonito is a medium-sized fish that can reach speeds of up to 40 mph . These fish thrive in warm waters and grow to a size of between 18 and 30 inches.

They have a slim and muscular body, perfectly shaped for fast swimming. Bonito also have powerful tail fins that act like a natural motor, helping them glide effortlessly through the water.

Their speed is not just for hunting; it’s also crucial for escaping danger and their long migrations across the sea. Additionally, these fish are valuable both for commercial fishing and as a catch for sport fishermen.

Interestingly, the term “Bonito” describes several species of medium-sized, ray-finned predatory fish. Some notable examples are Striped Bonito, Atlantic Bonito, and Pacific Bonito.

9. Blue Shark (43 mph)

The Blue Shark, holding the ninth spot on our list, impresses with its 43 mph pace. These sharks, ranging in size from 72 to 144 inches , are found mainly in deep, warm, and cool areas.

Their long bodies and big side fins are perfect for fast swimming. These features allow them to chase food or travel far.

Regarding physical appearance, these sharks stand out with their bright blue color, which is also where they got their name.

What’s really special about these creatures is how they hunt food. Recent studies discovered that blue sharks rely on large, spinning currents, known as eddies, to quickly reach the ocean’s twilight zone .

By riding these currents, blue sharks can conserve energy while traveling to deeper parts of the ocean, where food might be more abundant.

This behavior shows their smart use of ocean dynamics to make hunting more efficient rather than relying only on their speed.

8. Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (44 mph)

The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is an incredible fish that can swim up to 44 mph . It has a body shaped like a torpedo and strong muscles suited for fast swimming.

These fish travel long distances, swimming through the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. They are also big, growing up to 60 to 150 inches long.

The largest Atlantic Bluefin Tuna I’ve seen in person measured an impressive 832 pounds . It was caught off Florida’s Panhandle coast, a few hours from my childhood town in Boca Raton.

I remember that it took six men to lift the tuna from the water using a rope and a pulley. It was definitely one of the largest tuna I came across.

Aside from their size and speed, another amazing thing about these fast sea animals is that they can keep their body warm in different water temperatures.

On top of that, their color is striking, too, sporting a shiny blue back and a white belly.

Fun Fact: Did you know that after disappearing for over 50 years , the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna has made a spectacular comeback to Nordic waters?

This return is a chance for fish enthusiasts to learn more about their migration and behavior in a region they last visited in decades.

7. Pilot Whale (47 mph)

The Pilot Whale, known for swimming as fast as 47 mph , is next in line in our list of fast sea animals. These animals, which can be as long as 240 inches , are actually more similar to large dolphins than to true whales.

Their impressive speed is thanks to their streamlined bodies and powerful flukes, which enable swift and agile movements.

Pilot Whales are social creatures, often found in large pods. They use their speed for efficient hunting and evading predators.

The term “pilot whale” likely comes from the idea that these whales have a leader, or “pilot,” in their groups.

People thought this because they saw pilot whales swimming together in pods, usually following one or a few whales that seemed to lead the way. However, this idea is more folklore rather than a proven scientific fact.

Fun Fact: On July 18, 2023, 97 pilot whales were stranded near Albany, Western Australia. The exact cause of this is unknown and is currently being investigated. Some say it’s acoustic trauma, while other scientists believe a disease may cause it.

6. Wahoo (48 mph)

The Wahoo ranks sixth among our list of ocean speedsters. These fish have the ability to swim at 48 mph thanks to their elongated bodies and streamlined shape.

Found in tropical and subtropical seas worldwide, Wahoos are known for their blue-green backs and silvery sides. Their agility and speed make them a favorite among sport fishermen.

Intriguingly, satellite tagging studies have shown that Wahoos spend most of their time in shallow waters. This behavior is quite special and different.

Unlike other fast-swimming animals, Wahoos don’t usually go deep to find food or escape danger. This shows they have found a special way to live suited to their needs and abilities.

5. Yellowfin Tuna (50 mph)

The Yellowfin Tuna, zipping through the water at 50 mph , snags the title of fifth fastest sea creature. Its body is shaped like a torpedo, sleek and streamlined, which helps it cut through water quickly.

There are many theories as to how Yellowfin Tuna is so fast, but one study I came across credits their muscle structure for their speed.

Unlike other fish with only white, anaerobic fibers , Yellowfin Tuna have red, anaerobic fibers deep in their muscular structure. This design is said to boost their swimming power.

However, the presence of red aerobic fibers is not unique to them. In fact, I have come across other fish that also have these muscular fibers.

Under a microscope, I would describe these red aerobic fibers as long, striated muscle fibers with a reddish tint. This is due to the high content of myoglobin, an oxygen-storing protein.

Going back to the Yellowfin Tuna, another cool thing about them is how they hang out with other sea animals, like dolphins. This shows they like being part of a group, which makes them even more fascinating.

4. Dolphinfish (Mahi Mahi) (58 mph)

The Dolphinfish, also called Mahi Mahi, is a fast sea animal that can swim as fast as 58 mph . Its streamlined body shape helps it move quickly through the water.

Other than their speed, these fish are also known for their striking colors, ranging from golden yellow to bright blue and green. In terms of size, they can grow quite large, up to 63 inches long .

One interesting thing about Dolphinfish is that they grow really quickly. On average, they can grow up to 2.7 inches per week and reach their adult size in about a year.

Furthermore, they reach their sexual maturity as early as five months of age. This exceptional growth rate is among the highest for bony fishes.

Fun Fact: In 2014, a captive Mahi Mahi was recorded to have grown 50 pounds in just nine months . This is an incredibly fast growth rate for any sea animal.

3. Swordfish (62 mph)

The Swordfish, known for reaching speeds as high as 62 mph , stands out as one of the fastest sea animals. A big reason for its remarkable speed is its body shape and long bill.

However, aside from their streamlined figure, Swordfish also have a special gland that releases oil. This creates a slick coating on their skin, which reduces water drag.

Swordfish also have small, tooth-like features called denticles. These structures, combined with the oil, create a water-repelling effect.

This unique combination enables Swordfish to reach speeds that rival the swiftness of a cheetah on land.

Size-wise, Swordfish are big, growing up to 118 inches . Their large size and speed make them incredibly efficient and powerful swimmers in the sea.

2. Sailfish (68 mph)

The Sailfish is known to many as the ocean’s fastest fish, but it is actually just the second fastest. Boasting a speed of around 68 mph , these creatures sport a perfectly shaped body and a long, sword-like bill.

When hunting for prey, Sailfish usually move between the ocean’s surface and deeper, colder layers. They are also fond of hunting in groups.

However, recent studies have shown something new: Sailfish also hunt alone. In a 2023 study , researchers were able to film a Sailfish chasing a small tuna from deep underwater to the surface.

The research also mentioned that a Sailfish needs to consume roughly half a tuna per day to meet its energy needs. This is quite impressive, considering the amount of energy it needs to hunt and swim fast.

Watch this video to learn more about this study on Sailfish:

Fun Fact: There is a study challenging claims about the high-speed swimming abilities of fish. It examines the muscle contraction times in Sailfish, revealing that they swim much slower than previously believed. Debates on this topic are still ongoing.

1. Black Marlin (82 mph)

The Black Marlin, known as the fastest fish in the ocean, can reach speeds of up to 82 mph . BBC News shared a video supporting this claim. It shows just how fast the fishing reel unwinds when a Black Marlin is caught.

The video shows the fishing line unwinding at an estimated 120 feet per second , which is around 82 mph. Some people question if this is a precise way to measure speed, but others believe it’s pretty convincing.

Apart from their speed, though, Black Marlins are also known for their impressive jumps out of the water. These leaps show how strong they are and help them get rid of parasites and avoid predators.

Black Marlins are also popular targets in sport fishing because of their large size and the challenge they offer to anglers. However, fishing for them is carefully regulated in many places.

Watch this video to get a sense of how fast the Black Marlin is:

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Fastest Fish in the World?

The Black Marlin is known as the fastest fish in the world, capable of reaching speeds up to 82 mph (132 km/h). However, other sources point to the Sailfish as the fastest, clocking in at an impressive 68 mph (109 km/h).

Is a Black Marlin Faster Than a Cheetah?

Yes, in water. A Black Marlin can swim up to 82 mph, while a cheetah, the fastest land animal, can run up to 75 mph. However, this comparison is between different mediums (water vs. land).

What Factors Contribute to the Speed of Sea Animals?

The speed of sea animals depends on a few things, like their body shape, muscular strength, the size and shape of their fins, and sometimes special features (such as oil glands in the case of the Sailfish).

So, what do you think about these amazing sea creatures? Did they impress you? Let us know your thoughts and ideas about these fast sea animals by leaving a comment below!

Daniel Bradley

I'm Daniel Bradley, a marine biologist and experienced angler with a deep love for fish and marine ecosystems. Through my blog, I share insights on marine species, conservation issues, and my personal experiences from fishing and exploring marine sanctuaries, aiming to inspire and educate others about the underwater world.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

You may also like, do orcas eat moose, is a seahorse a fish or a mammal, top 8 rarest lobster colors: ranked by rarity, what kind of symmetry does a starfish have, how many arms does a starfish have, do octopuses die after giving birth, octopus suction cups: everything you need to know, how do octopuses change color (and why), do male seahorses give birth (yes, and here’s how), are coconut crabs dangerous to humans, how many arms or tentacles does an octopus have, what is a group of octopuses called, what do octopuses eat (9 favorite foods of octopuses), 11 different jellyfish colors explained, do octopuses have ink (and what is it made of), what is a group of sharks called (4 common terms), octopus brain & intelligence: how smart are octopuses, can you eat coconut crabs (what does it taste like), crayfish vs. lobster: what are the differences, what does a blobfish look like underwater, squid vs. octopus: what are the differences, 18 different types of ocean plants, what is a baby whale called (with pictures & facts), are fish mammals (no, and here’s why), how many arms and tentacles does a squid have, do octopuses make good pets – things you need to know, 26 different types of jellyfish in the ocean, how long do octopuses live (in the wild & in captivity), are there any freshwater octopuses, what is a group of jellyfish called.

The Fastest Fish in the World

It's claimed that some species top 80 mph

- Marine Life Profiles

- Marine Habitat Profiles

- Habitat Profiles

- M.S., Resource Administration and Management, University of New Hampshire

- B.S., Natural Resources, Cornell University

For the average landlubber, fish often seem strange . It isn't easy to measure the speed of fish, whether they're swimming wild in the open sea, tugging on your line, or splashing in a tank. Still, wildlife experts have enough information to conclude that these are likely the world's fastest fish species, all of which are highly prized by commercial and recreational fishermen.

Sailfish (68 mph)

Jens Kuhfs / Getty Images

Many sources list sailfish ( Istiophorus platypterus ) as the fastest fish in the ocean. They are definitely fast leapers, and likely one of the fastest fish at swimming short distances. Some speed trials describe a sailfish clocking in at 68 mph while leaping.

Sailfish can grow to 10 feet long and, though slim, weigh up to 128 pounds. Their most noticeable characteristics are their large first dorsal fin, which resembles a sail, and their upper jaw, which is long and spear-like. Sailfish have blue-gray backs and white undersides.

Sailfish are found in temperate and tropical waters in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. They feed primarily on small bony fish and cephalopods , which include squids, cuttlefish, and octopuses.

Swordfish (60-80 mph)

The swordfish ( Xiphias gladius ) is a popular seafood and another fast-leaping species, although its speed is not well known. One calculation determined that they could swim at 60 mph, while another finding claimed speeds of over 80 mph.

The swordfish has a long, sword-like bill, which it uses to spear or slash its prey. It has a tall dorsal fin and a brownish-black back with a light underside.

Swordfish are found in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, and in the Mediterranean Sea. The film "The Perfect Storm," based on the book by Sebastian Junger, is about a Gloucester, Massachusetts, swordfishing boat lost at sea during a 1991 storm.

Marlin (80 mph)

Marlin species include the Atlantic blue marlin ( Makaira nigricans ), black marlin ( Makaira indica) , Indo-Pacific blue marlin ( Makaira mazara ), striped marlin ( Tetrapturus audax ), and white marlin ( Tetrapturus albidus ). They are easily recognized by their long, spear-like upper jaw and tall first dorsal fin.

The BBC has claimed that the black marlin is the fastest fish on the planet, based on a marlin caught on a fishing line. It was said to have stripped line off a reel at 120 feet per second, meaning the fish was swimming nearly 82 mph. Another source said marlins could leap at 50 mph.

Wahoo (48 mph)

The wahoo ( Acanthocybium solandri ) lives in tropical and subtropical waters in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, and the Caribbean and Mediterranean Seas. These slender fish have bluish-green backs with light sides and bellies. They can grow to 8 feet long, but more commonly reach 5 feet. Scientists studying the wahoo's speed reported that it reached 48 mph in bursts.

Tuna (46 mph)

Although yellowfin ( Thunnus albacares ) and bluefin tuna ( Thunnus thynnus ) appear to cruise slowly through the ocean, they can have bursts of speed over 40 mph. The wahoo study cited above also measured a yellowfin tuna's burst of speed at just over 46 mph. Another site lists the maximum leaping speed of an Atlantic bluefin tuna at 43.4 mph.

Bluefin tuna can reach lengths over 10 feet. Atlantic bluefin are found in the western Atlantic from Newfoundland, Canada, to the Gulf of Mexico , in the eastern Atlantic from Iceland to the Canary Islands, and throughout the Mediterranean Sea. Southern bluefin are seen throughout the southern hemisphere in latitudes between 30 and 50 degrees.

Yellowfin tuna, found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, can top 7 feet in length. Albacore tuna, capable of speeds up to 40 mph, are found in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the Mediterranean Sea. They are commonly sold as canned tuna. Their maximum size is 4 feet and 88 pounds.

Bonito (40 mph)

Ian O'Leary / Getty Images

Bonito, a common name for fish in the genus Sarda , comprises species in the mackerel family, including the Atlantic bonito, striped bonito, and Pacific bonito. Bonito are said to be capable of leaping speeds of 40 mph. Bonito, a streamlined fish with striped sides, grow to 30 to 40 inches.

- Tuna Species Types

- Blue Marlin Facts

- Swordfish: Habitat, Behavior, and Diet

- The Fastest Animals on the Planet

- Shark Species

- The Mako Shark

- Types of Toothed Whales

- Yellowfin Tuna Facts (Thunnus albacares)

- What Is the Biggest Fish in the World?

- Identification of Jellyfish and Jelly-like Animals

- Spinner Dolphin

- Ocean Sunfish Facts

- 19 Types of Whales

- Barracuda: Habitat, Behavior, and Diet

- How Fast Can a Shark Swim?

- Catalogue of Hammerhead Sharks

Wildlife Informer is reader-supported. When you click and buy we may earn an affiliate commission at no cost to you. Learn more.

14 Examples of Migratory Fish Species

Millions of fish from various species will migrate every year. Some migrate to reproduce, while others migrate looking for food. No matter what the reason, many fish will swim thousands of miles throughout rivers and oceans during the process. Let’s take a look at 14 different species of migratory fish.

14 Types of Migratory Fish

Migration is an important and vital part of the animal kingdom, especially for fish. During this time, the aquatic creatures will move from one area to the next. While food and breeding is the most common reason for fish migration, some species will also migrate to stay either warm in the winter or cool in the summer.

Scientific Name: Salmo salar

Salmon is arguably the most well-known migratory fish. The actual migratory pattern, however, will vary from one species of salmon to the next. For example, the North American Atlantic salmon will migrate from their birth rivers in the spring and move to the Labrador Sea.

2. Mekong Giant Catfish

Scientific Name: Pangasianodon gigas

The Mekong giant catfish is much larger than the catfish commonly found in the United States. These impressive creatures can reach lengths of over 9 feet and weight more than 700 pounds.

Even though they may appear scary, they are gentle giants that feed on invertebrates and algae. The Mekong giant catfish is, unfortunately, listed as critically endangered . Because their numbers have diminished, researchers rarely see them in the wild.

3. Skipjack Tuna

Scientific Name: Katsuwonus pelamis

Skipjack tuna is another migratory fish that swims long distances in order to reproduce and find food. They typically love in open oceans, but can sometimes spend their lives in waters near the shore. While not yet listed as endangered, it is feared that the skipjack tuna could potentially slip into that category due to overfishing.

4. Swordfish

Scientific Name: Xiphias gladius

Swordfish migrate seasonally to cooler waters during the summer and then warmer waters in the winter. The exact migration pattern for swordfish varies from one species to the next. The North Atlantic swordfish, for example, migrates from the eastern seaboard in Canada and the United States to the eastern Atlantic in Europe and Africa.

5. Beluga Sturgeon

Scientific Name: Huso huso

Beluga sturgeons can weight over 3,000 pounds, and this large species of fish is actually one of the oldest . Research has shown that sturgeons were around 50 million years before birds!

The beluga sturgeon migrates to freshwater rivers from the sea, where they will spawn. These migrations happen twice a year, during the spring and fall. Unfortunately, this species is listed as critically endangered due to overfishing and loss of its natural habitat.

6. Hawaiian Freshwater Goby

Scientific Name: Lentipes concolor

Despite their small size, the Hawaiian freshwater goby’s migration is a surprisingly long journey. As juveniles, these fish will travel from the sea to freshwater streams and stay there until they reach adulthood.

They use their sucker-like mouths and fins to make their way up slippery rocks until they reach a mountain stream. It is here where they will lay their eggs, which will then float down the stream and into the sea. Once the eggs reach the sea, they will hatch and the cycle will begin again.

Scientific Name: Istiophoridae

Marlins may not be as high on the food chain as sharks, but they are not far behind. They have long, sharp bills and pointed fins.

These fish migrate seasonally from the Gulf of Mexico or the Middle Atlantic to southern Caribbean. Unfortunately, the number of marlins in the wild are starting to decline due to fisherman catching and killing them.

8. American Paddlefish

Scientific Name: Polyodon spathula

The American paddlefish is an unusual-looking creature with a long paddle-like snout. This freshwater fish is a filter feeder whose migration can expand over 2,000 miles.

Despite being a freshwater fish, these interesting creatures can swim through areas where saltwater mixes with freshwater, which is known as brackish water .

Scientific Name: Bramidae

Pomfrets are teardrop-shaped fish and their size varies from one species to the next. The migration pattern of the pomfret depends on the temperature of the waters.

However, that isn’t the only thing that can affect its migration. The climatic conditions of the surface, as well as the density can directly affect when and where the fish migrates.

10. Sailfish

Scientific Name: Istiophorus

Sailfish are typically considered a near-shore species of fish, although they can dive over 300 feet deep. These stunning fish are related to the marlins, and have long spears that extend from their snouts.

It’s body has a deep blue hue with a silver underside, and a bright blue dorsal fin that has a spotted pattern. Sailfish migrate due to water temperature changes, and will head to warmer waters in the fall and cooler waters in the spring.

Scientific Name: Acanthocybium solandri

Wahoos follow the migration pattern of their prey, which are squid, mackerel, round herring, porcupine fish, and butterfish. The wahoo has a steel blue body and pale blue underside, and features a vertical bar-like pattern on its sides. An interesting fact about this pattern is that, after the fish dies, these bars will rapidly fade.

12. Steelhead Trout

Scientific Name: Oncorhynchus mykiss

Steelhead trout are one of the top sport fish in North America. They are not overly large fish, and typically measure less than 45 inches long.

The migration of these fish is triggered when there are more hours during the day, which occurs in the spring. They migrate upstream to spawn, and some steelhead trouts will even migrate more than 500 miles until they reach their desired spawning location.

13. Alewives

Scientific Name: Alosa pseudoharengus

Alewives seasonal migration occurs when the water temperature reaches a certain temperature. At this time, they will return to the river where they were born. They migrate from freshwater rivers all the way to the ocean, and then back to freshwater where they will spawn.

Scientific Name: Alosa sapidissima

The body color of the shad can vary from one species to another, but they typically range from a greenish hue to a dark blue color. They are covered in scales that shade easily and have a forked tail fin.

Shads will begin their migration when the water temperatures start to decrease in later summer to early fall, and they will make their way to warmer waters.

WildlifeInformer.com is your #1 source for free information about all types of wildlife and exotic pets. We also share helpful tips and guides on a variety of topics related to animals and nature.

Long-Distance Ocean Travels

Follow along travel routes of oceanic species.

Biology, Earth Science, Oceanography, Geography

Loading ...

This resource is also available in Spanish .

Each map in this gallery depicts the travel routes of oceanic species. The organisms mapped are whales, sharks, pinnipeds, sea turtles, seabirds, and bluefin tuna. The organisms are mapped by separating them into their various communities across the Pacific, Atlantic, Southern, and Indian oceans.

The Census of Marine Life

For millennia, the ocean has enchanted human imagination with the lure of treasure, monsters, and mystery, all hidden beneath a seemingly endless surface . Centuries of exploration have revealed wonders beneath the waves, but much more remains to be discovered. Facets of oceanography and marine biology remain only partially understood; including questions about the diversity, distribution, and abundance of the life that dwells in the ocean .

A collaboration of scientists working with unprecedented scope has provided a push to answer many of these questions. In the year 2000, the first Census of Marine Life began a 10-year effort to reveal the state of life in the ocean . Enrolling some 2,700 researchers from more than 80 countries, it employed divers, nets, and submersible vehicles, genetic identification, sonars , electronic and acoustic tagging, listening posts, and communicating satellites. The Census spanned all oceanic realms , from coasts , down slopes , to the abyss , from the North Pole across tropics to the shores of Antarctica. It systematically compiled information from new discoveries and historic archives and made it freely accessible. Census explorers found life wherever they looked—a riot of species.

The last decade has improved our understanding of the very small, the very large, and very remote creatures that call the ocean home. Marine life continues to bring forth surprises. In the Caribbean, explorers encountered a clam that thrived between 200 million and 65 million years ago, but thought to have been extinct since the early 1880s. Off Mauritania, they found cold-water corals extending over 400 kilometers (249 miles) at a depth of 500 meters (1,640 feet)—one of the world's longest reefs. Near Chile, they found giant microbial mats covering an area of seafloor the size of Greece. Long-term tracking revealed migratory highways. Combining all this information has created a deeper understanding of new habitats and ecosystems , and also of habitats that have a long history of human contact.

About this Gallery: Long-distance Ocean Travels

This map gallery offers a glimpse into the discoveries of a decade 's investigation into life in all ocean realms from microbes to whales. As modern tracking technology follows animals over ever-longer distances and durations, the last decade has revealed the largest daily migration and the longest seasonal migration yet observed. The eventual goal is to define migratory corridors of the oceans : the "blue highways."

Each map in this gallery was created by combining data collected by tracking multiple organisms of one species. Each map contains multiple tracks and points because multiple organisms are mapped, and different organisms travel different places. By mapping multiple organisms, patterns emerge, allowing researchers to define the "blue highways" that they seek.

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Page Producers

Maps courtesy Census of Marine Life

Individual map credits are as follows:

Pacific Bluefin Tuna

TAGGING OF PACIFIC PREDATORS

LEAD: BLOCK, WWW.TOPP.ORG

Pacific Whales

LEAD: MATE, WWW.TOPP.ORG

Pacific Sea Turtles

LEAD: SHILLINGER (EAST), BENSON (WEST), WWW.TOPP.ORG

Pacific Seabirds

LEAD: SHAFFER, WWW.TOPP.ORG

Pacific Sharks

Pacific Pinnipeds

LEAD: COSTA, WWW.TOPP.ORG

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

BLOCK ET AL. (2005), WWW.TAGAGIANT.ORG

Atlantic Sea Turtles

MCCLELLAN (2007), GODLEY (2004), MACHADO (2010) AGGREGATED AT WWW.SEAMAP.ENV.DUKE.EDU

Atlantic Seabirds

MARTIN ET AL (2010), WWW.SEAMAP.ENV.DUKE.EDU

Southern Pinnipeds

BIUW ET AL. (2007), WWW.BIOLOGY.ST-ANDREWS.AC.UK/SEAOS/

Indian Ocean White Sharks

BONFIL ET AL. (2005), WWW.SHARK-TRACKER.COM

Last Updated

March 8, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Fast But Not Furious: The Top 10 Quickest Fish

There are more than 33,000 species of fish on this planet, but not all of them can be described as speedy. The fastest fish can put up a great fight when you’re trying to catch them. Some of the fastest fish that we detail below can move faster than the average highway speed limit, while others move just as quickly out of the water as they do beneath the surface.

Everything you will learn here

10. Shortfin Mako Shark

9. little tunny, 8. atlantic bluefin tuna, 7. bonefish, 6. blue shark, 4. striped marlin, 3. swordfish, 2. sailfish, 1. black marlin, a few other speedy fish worthy of mention, top 10 fastest fish.

Ready to learn about some of the ocean’s quickest creatures? Here’s a detailed list of the fastest fish under the sea:

This predator lives in the open ocean and reaches lengths of up to 12 feet and weights of about 1,200 pounds. They swim up to 45 miles an hour, moving swiftly to capture their prey. They can withstand cool water because they have a circulatory system that’s similar to the tuna’s. These predators are at the top of the pelagic food chain.

Unfortunately, shortfin mako shark numbers are dwindling. Detrimental fishing practices are causing these fish to become vulnerable to extinction.

The little tunny, also called false albacore, can strip a fishing line while swimming at 40 mph.

This fish may not be the fastest in the ocean, but it’s in the top ten and makes for excellent sport fishing.

Its streamlined body makes it swift in the water. This fish is more compact than other types of tuna. Due to its body composition, this fish has endurance as well as speed.

Although you might think that this fish gets its name from its similarity to the tuna, it doesn’t. “Tunny” comes from a Greek word that means “to rush” or “to dart.” Shaped like a torpedo, this fish moves like a bullet.

The Atlantic bluefin tuna is impressive for several reasons. It is the largest tuna, growing up to 3 feet long within three to five years of age. But when this fish hatches, it is almost microscopic. It grows to be one of the biggest predators in the open ocean.

Atlantic bluefin tuna reach speeds of up to 40 mph and go on long migrations each year. They can also dive up to 3,300 feet below the ocean’s surface. They must keep moving to gather oxygen from the water in order to survive.

All fish are cold-blooded, which means that they take on the temperature of the surrounding environment. Bluefin tuna have a distinct blood vessel configuration, which keeps them warmer than the water around them. This may not help them swim fast, but it allows them to stay warm in cooler parts of the ocean.