Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 22 September 2016

Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: a dynamic framework

- Kalina Christoff 1 , 2 ,

- Zachary C. Irving 3 ,

- Kieran C. R. Fox 1 ,

- R. Nathan Spreng 4 , 5 &

- Jessica R. Andrews-Hanna 6

Nature Reviews Neuroscience volume 17 , pages 718–731 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

673 Citations

493 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive control

- Schizophrenia

In the past 15 years, mind-wandering has become a prominent topic in cognitive neuroscience and psychology. Whereas mind-wandering has come to be predominantly defined as task-unrelated and/or stimulus-unrelated thought, we argue that this content-based definition fails to capture the defining quality of mind-wandering: the relatively free and spontaneous arising of mental states as the mind wanders.

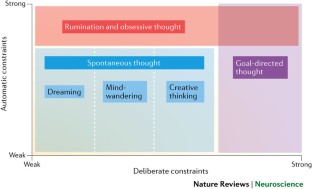

We define spontaneous thought as a mental state, or a sequence of mental states, that arises relatively freely due to an absence of strong constraints on the contents of each state and on the transitions from one mental state to another. We propose that there are two general ways in which the content of mental states, and the transitions between them, can be constrained.

Deliberate and automatic constraints serve to limit the contents of thought and how these contents change over time. Deliberate constraints are implemented through cognitive control, whereas automatic constraints can be considered as a family of mechanisms that operate outside of cognitive control, including sensory or affective salience.

Within our framework, mind-wandering can be defined as a special case of spontaneous thought that tends to be more deliberately constrained than dreaming, but less deliberately constrained than creative thinking and goal-directed thought. In addition, mind-wandering can be clearly distinguished from rumination and other types of thought that are marked by a high degree of automatic constraints, such as obsessive thought.

In general, deliberate constraints are minimal during dreaming, tend to increase somewhat during mind-wandering, increase further during creative thinking and are strongest during goal-directed thought. There is a range of low-to-medium level of automatic constraints that can occur during dreaming, mind-wandering and creative thinking, but thought ceases to be spontaneous at the strongest levels of automatic constraint, such as during rumination or obsessive thought.

We propose a neural model of the interactions among sources of variability, automatic constraints and deliberate constraints on thought: the default network (DN) subsystem centred around the medial temporal lobe (MTL) (DN MTL ) and sensorimotor areas can act as sources of variability; the salience networks, the dorsal attention network (DAN) and the core DN subsystem (DN CORE ) can exert automatic constraints on the output of the DN MTL and sensorimotor areas, thus limiting the variability of thought; and the frontoparietal control network can exert deliberate constraints on thought by flexibly coupling with the DN CORE , the DAN or the salience networks, thus reinforcing or reducing the automatic constraints being exerted by the DN CORE , the DAN or the salience networks.

Most research on mind-wandering has characterized it as a mental state with contents that are task unrelated or stimulus independent. However, the dynamics of mind-wandering — how mental states change over time — have remained largely neglected. Here, we introduce a dynamic framework for understanding mind-wandering and its relationship to the recruitment of large-scale brain networks. We propose that mind-wandering is best understood as a member of a family of spontaneous-thought phenomena that also includes creative thought and dreaming. This dynamic framework can shed new light on mental disorders that are marked by alterations in spontaneous thought, including depression, anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

176,64 € per year

only 14,72 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

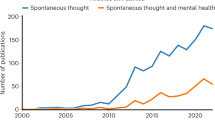

Recent advances in the neuroscience of spontaneous and off-task thought: implications for mental health

Aaron Kucyi, Julia W. Y. Kam, … Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli

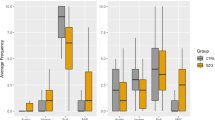

Introspective and Neurophysiological Measures of Mind Wandering in Schizophrenia

S. Iglesias-Parro, M. F. Soriano, … A. J. Ibáñez-Molina

Prediction of stimulus-independent and task-unrelated thought from functional brain networks

Aaron Kucyi, Michael Esterman, … Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli

James, W. The Principles of Psychology (Henry Holt and Company, 1890).

Google Scholar

Callard, F., Smallwood, J., Golchert, J. & Margulies, D. S. The era of the wandering mind? Twenty-first century research on self-generated mental activity. Front. Psychol. 4 , 891 (2013).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Andreasen, N. C. et al. Remembering the past: two facets of episodic memory explored with positron emission tomography. Am. J. Psychiatry 152 , 1576–1585 (1995).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Binder, J. R., Frost, J. A. & Hammeke, T. A. Conceptual processing during the conscious resting state: a functional MRI study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 11 , 80–93 (1999).

Stark, C. E. & Squire, L. R. When zero is not zero: the problem of ambiguous baseline conditions in fMRI. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98 , 12760–12766 (2001).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Christoff, K. & Gabrieli, J. D. E. The frontopolar cortex and human cognition: evidence for a rostrocaudal hierarchical organization within the human prefrontal cortex. Psychobiology 28 , 168–186 (2000).

Shulman, G. L. et al. Common blood flow changes across visual tasks: II. Decreases cerebral cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 9 , 648–663 (1997). This meta-analysis provides convincing evidence that a set of specific brain regions, which later became known as the default mode network, becomes consistently activated during rest.

Raichle, M. E. et al. A default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98 , 676–682 (2001). This highly influential theoretical paper coined the term 'default mode' to refer to cognitive and neural processes that occur in the absence of external task demands.

Singer, J. L. Daydreaming: An Introduction to the Experimental Study of Inner Experience (Random House, 1966).

Antrobus, J. S. Information theory and stimulus-independent thought. Br. J. Psychol. 59 , 423–430 (1968).

Antrobus, J. S., Singer, J. L., Goldstein, S. & Fortgang, M. Mind wandering and cognitive structure. Trans. NY Acad. Sci. 32 , 242–252 (1970).

CAS Google Scholar

Filler, M. S. & Giambra, L. M. Daydreaming as a function of cueing and task difficulty. Percept. Mot. Skills 37 , 503–509 (1973).

Giambra, L. M. Adult male daydreaming across the life span: a replication, further analyses, and tentative norms based upon retrospective reports. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 8 , 197–228 (1977).

PubMed Google Scholar

Giambra, L. M. Sex differences in daydreaming and related mental activity from the late teens to the early nineties. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 10 , 1–34 (1979).

Klinger, E. & Cox, W. M. Dimensions of thought flow in everyday life. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 7 , 105–128 (1987). This is probably the earliest experience sampling study of mind-wandering in daily life, revealing that adults spend approximately one-third of their waking life engaged in undirected thinking.

Giambra, L. M. Task-unrelated-thought frequency as a function of age: a laboratory study. Psychol. Aging 4 , 136–143 (1989).

Teasdale, J. D., Proctor, L., Lloyd, C. A. & Baddeley, A. D. Working memory and stimulus-independent thought: effects of memory load and presentation rate. Eur. J. Cogn. Psychol. 5 , 417–433 (1993).

Giambra, L. M. A laboratory method for investigating influences on switching attention to task-unrelated imagery and thought. Conscious. Cogn. 4 , 1–21 (1995).

Klinger, E. Structure and Functions of Fantasy (John Wiley & Sons, 1971). This pioneering book summarizes the early empirical research on daydreaming and introduces important theoretical hypotheses, including the idea that task-unrelated thoughts are often about 'current concerns'.

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The restless mind. Psychol. Bull. 132 , 946–958 (2006). This paper put mind-wandering in the forefront of psychological research, advancing the influential hypothesis that executive resources support mind-wandering.

Killingsworth, M. A. & Gilbert, D. T. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330 , 932 (2010).

Mason, M. F. et al. Wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science 315 , 393–395 (2007). This influential paper brought mind-wandering to the forefront of neuroscientific research, arguing for a link between DN recruitment and stimulus-independent thought.

Christoff, K., Gordon, A. M., Smallwood, J., Smith, R. & Schooler, J. W. Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 , 8719–8724 (2009). This paper is the first to use online experience sampling to examine the neural correlates of mind-wandering and the first to find joint activation of the DN and executive network during this phenomenon.

Callard, F., Smallwood, J. & Margulies, D. S. Default positions: how neuroscience's historical legacy has hampered investigation of the resting mind. Front. Psychol. 3 , 321 (2012).

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The science of mind wandering: empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66 , 487–518 (2015). This comprehensive review synthesizes the recent research characterizing mind-wandering as task-unrelated and/or stimulus-independent thought.

Christoff, K. Undirected thought: neural determinants and correlates. Brain Res. 1428 , 51–59 (2012). This review disambiguates between different definitions of spontaneous thought and mind-wandering, and it argues that current definitions do not capture the dynamics of thought.

Irving, Z. C. Mind-wandering is unguided attention: accounting for the 'purposeful' wanderer. Philos. Stud. 173 , 547–571 (2016). This is one of the first philosophical theories of mind-wandering; this paper defines mind-wandering as unguided attention to explain why its dynamics contrast with automatically and deliberately guided forms of attention such as rumination and goal-directed thinking.

Carruthers, P. The Centered Mind: What the Science of Working Memory Shows Us About the Nature of Human Thought (Oxford Univ. Press, 2015).

Simpson, J. A. The Oxford English Dictionary (Clarendon Press, 1989).

Kane, M. J. et al. For whom the mind wanders, and when: an experience-sampling study of working memory and executive control in daily life. Psychol. Sci. 18 , 614–621 (2007). This study of mind-wandering in everyday life is one of the most important investigations into the complex relationship between mind-wandering and executive control.

Baird, B., Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. Back to the future: autobiographical planning and the functionality of mind-wandering. Conscious. Cogn. 20 , 1604–1611 (2011).

Morsella, E., Ben-Zeev, A., Lanska, M. & Bargh, J. A. The spontaneous thoughts of the night: how future tasks breed intrusive cognitions. Social Cogn. 28 , 641–650 (2010).

Miller, E. K. & Cohen, J. D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24 , 167–202 (2001).

Miller, E. K. The prefrontal cortex and cognitive control. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1 , 59–65 (2000).

Markovic, J., Anderson, A. K. & Todd, R. M. Tuning to the significant: neural and genetic processes underlying affective enhancement of visual perception and memory. Behav. Brain Res. 259 , 229–241 (2014).

Todd, R. M., Cunningham, W. A., Anderson, A. K. & Thompson, E. Affect-biased attention as emotion regulation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 365–372 (2012).

Pessoa, L. The Cognitive-Emotional Brain: From Interactions to Integration (MIT Press, 2013).

Jonides, J. & Yantis, S. Uniqueness of abrupt visual onset in capturing attention. Percept. Psychophys. 43 , 346–354 (1988).

Christoff, K., Gordon, A. M. & Smith, R. in Neuroscience of Decision Making (eds Vartanian, O. & Mandel, D. R.) 259–284 (Psychology Press, 2011).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maj, M., Van der Linden, M. & D'Argembeau, A. Mind-wandering: phenomenology and function as assessed with a novel experience sampling method. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 136 , 370–381 (2011).

Spreng, R. N., Mar, R. A. & Kim, A. S. N. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21 , 489–510 (2009). This paper provides some of the first quantitative evidence that the DN is associated with multiple cognitive functions.

Andrews-Hanna, J. R. The brain's default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. Neuroscientist 18 , 251–270 (2012). This recent review describes a large-scale functional meta-analysis on the cognitive functions, functional subdivisions and clinical dysfunction of the DN.

Buckner, R. L. & Carroll, D. C. Self-projection and the brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11 , 49–57 (2007).

Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Schacter, D. L. The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1124 , 1–38 (2008). This comprehensive review bridges across neuroscience, psychology and clinical research, and introduces a prominent hypothesis — the 'internal mentation hypothesis' — that the DN has an important role in spontaneous and directed forms of internal mentation.

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Reidler, J. S., Sepulcre, J., Poulin, R. & Buckner, R. L. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain's default network. Neuron 65 , 550–562 (2010).

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R. & Buckner, R. L. Remembering the past to imagine the future: the prospective brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8 , 657–661 (2007).

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Smallwood, J. & Spreng, R. N. The default network and self-generated thought: component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1316 , 29–52 (2014).

Corbetta, M., Patel, G. & Shulman, G. L. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron 58 , 306–324 (2008). This paper outlines an influential theoretical framework that extends an earlier model by Corbetta and Shulman that drew a crucial distinction between the DAN and VAN.

Vanhaudenhuyse, A. et al. Two distinct neuronal networks mediate the awareness of environment and of self. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 570–578 (2011).

Smallwood, J. Distinguishing how from why the mind wanders: a process–occurrence framework for self-generated mental activity. Psychol. Bull. 139 , 519–535 (2013). This theoretical paper presents an important distinction between the events that determine when an experience initially occurs from the processes that sustain an experience over time.

Toro, R., Fox, P. T. & Paus, T. Functional coactivation map of the human brain. Cereb. Cortex 18 , 2553–2559 (2008).

Fox, M. D. et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102 , 9673–9678 (2005). This paper provides a unique insight into the functional antagonism between the default and dorsal attention systems.

CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Keller, C. J. et al. Neurophysiological investigation of spontaneous correlated and anticorrelated fluctuations of the BOLD signal. J. Neurosci. 33 , 6333–6342 (2013).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27 , 2349–2356 (2007). This paper is the first to name the salience network and characterize its functional neuroanatomy.

Kucyi, A., Hodaie, M. & Davis, K. D. Lateralization in intrinsic functional connectivity of the temporoparietal junction with salience- and attention-related brain networks. J. Neurophysiol. 108 , 3382–3392 (2012).

Power, J. D. et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 72 , 665–678 (2011).

Cole, M. W. et al. Multi-task connectivity reveals flexible hubs for adaptive task control. Nat. Neurosci. 16 , 1348–1355 (2013).

Vincent, J. L., Kahn, I., Snyder, A. Z., Raichle, M. E. & Buckner, R. L. Evidence for a frontoparietal control system revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 100 , 3328–3342 (2008).

Niendam, T. A. et al. Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 12 , 241–268 (2012).

Spreng, R. N., Stevens, W. D., Chamberlain, J. P., Gilmore, A. W. & Schacter, D. L. Default network activity, coupled with the frontoparietal control network, supports goal-directed cognition. Neuroimage 53 , 303–317 (2010). This paper demonstrates how the DN couples with the FPCN for personally salient, goal-directed information processing.

Dixon, M. L., Fox, K. C. R. & Christoff, K. A framework for understanding the relationship between externally and internally directed cognition. Neuropsychologia 62 , 321–330 (2014).

Dosenbach, N. U. F. et al. A core system for the implementation of task sets. Neuron 50 , 799–812 (2006).

Dosenbach, N. U. F. et al. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 11073–11078 (2007).

Dosenbach, N. U. F., Fair, D. A., Cohen, A. L., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12 , 99–105 (2008).

Yeo, B. T. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106 , 1125–1165 (2011). This seminal paper uses resting-state functional connectivity and clustering approaches in 1,000 individuals to parcellate the brain into seven canonical large-scale networks.

Najafi, M., McMenamin, B. W., Simon, J. Z. & Pessoa, L. Overlapping communities reveal rich structure in large-scale brain networks during rest and task conditions. Neuroimage 135 , 92–106 (2016).

McGuire, P. K., Paulesu, E., Frackowiak, R. S. & Frith, C. D. Brain activity during stimulus independent thought. Neuroreport 7 , 2095–2099 (1996).

McKiernan, K. A., D'Angelo, B. R., Kaufman, J. N. & Binder, J. R. Interrupting the 'stream of consciousness': an fMRI investigation. Neuroimage 29 , 1185–1191 (2006).

Gilbert, S. J., Dumontheil, I., Simons, J. S., Frith, C. D. & Burgess, P. W. Comment on 'wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought'. Science 317 , 43b (2007).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maquet, P. & D'Argembeau, A. Neural correlates of ongoing conscious experience: both task-unrelatedness and stimulus-independence are related to default network activity. PLoS ONE 6 , e16997 (2011).

Fox, K. C. R., Spreng, R. N., Ellamil, M., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Christoff, K. The wandering brain: meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of mind-wandering and related spontaneous thought processes. Neuroimage 111 , 611–621 (2015). This paper presents the first quantitative meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on task-unrelated and/or stimulus-independent thought, revealing the involvement of the DN and other large-scale networks that were not traditionally thought to play a part in mind-wandering.

Ingvar, D. H. 'Hyperfrontal' distribution of the cerebral grey matter flow in resting wakefulness; on the functional anatomy of the conscious state. Acta Neurol. Scand. 60 , 12–25 (1979). This paper by David Ingvar, a pioneer of human neuroimaging, provides the original observations that a resting brain is an active one and highlights the finding that prefrontal executive regions are active even at rest.

Christoff, K., Ream, J. M. & Gabrieli, J. D. E. Neural basis of spontaneous thought processes. Cortex 40 , 623–630 (2004).

D'Argembeau, A. et al. Self-referential reflective activity and its relationship with rest: a PET study. Neuroimage 25 , 616–624 (2005).

Spiers, H. J. & Maguire, E. A. Spontaneous mentalizing during an interactive real world task: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 44 , 1674–1682 (2006).

Wang, K. et al. Offline memory reprocessing: involvement of the brain's default network in spontaneous thought processes. PLoS ONE 4 , e4867 (2009).

Dumontheil, I., Gilbert, S. J., Frith, C. D. & Burgess, P. W. Recruitment of lateral rostral prefrontal cortex in spontaneous and task-related thoughts. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 63 , 1740–1756 (2010).

Posner, M. I. & Rothbart, M. K. Attention, self-regulation and consciousness. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 353 , 1915–1927 (1998).

Duncan, J. & Owen, A. M. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends Neurosci. 23 , 475–483 (2000).

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S. & Cohen, J. D. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol. Rev. 108 , 624–652 (2001).

Banich, M. T. Executive function: the search for an integrated account. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 18 , 89–94 (2009).

Prado, J., Chadha, A. & Booth, J. R. The brain network for deductive reasoning: a quantitative meta-analysis of 28 neuroimaging studies. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 3483–3497 (2011).

McVay, J. C. & Kane, M. J. Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008). Psychol. Bull. 136 , 188–197 (2010). This paper presents the theoretically influential control failure hypothesis, which is opposed to the thesis that executive function supports mind-wandering.

Kane, M. J. & McVay, J. C. What mind wandering reveals about executive-control abilities and failures. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 348–354 (2012).

Levinson, D. B., Smallwood, J. & Davidson, R. J. The persistence of thought: evidence for a role of working memory in the maintenance of task-unrelated thinking. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 375–380 (2012).

Salthouse, T. A., Fristoe, N., McGuthry, K. E. & Hambrick, D. Z. Relation of task switching to speed, age, and fluid intelligence. Psychol. Aging 13 , 445–461 (1998).

Maillet, D. & Schacter, D. L. From mind wandering to involuntary retrieval: age-related differences in spontaneous cognitive processes. Neuropsychologia 80 , 142–156 (2016).

Axelrod, V., Rees, G., Lavidor, M. & Bar, M. Increasing propensity to mind-wander with transcranial direct current stimulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 3314–3319 (2015).

Schooler, J. W. et al. Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15 , 319–326 (2011).

Smallwood, J., Beach, E. & Schooler, J. W. Going AWOL in the brain: mind wandering reduces cortical analysis of external events. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20 , 458–469 (2008).

Kam, J. W. Y. et al. Slow fluctuations in attentional control of sensory cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 460–470 (2011).

Gelbard-Sagiv, H., Mukamel, R., Harel, M., Malach, R. & Fried, I. Internally generated reactivation of single neurons in human hippocampus during free recall. Science 322 , 96–101 (2008). This pioneering study aimed to identify the neural origins of spontaneously recalled memories, finding strong evidence for the initial generation in the MTL.

Ellamil, M. et al. Dynamics of neural recruitment surrounding the spontaneous arising of thoughts in experienced mindfulness practitioners. Neuroimage 136 , 186–196 (2016). This study is the first to reveal a sequential recruitment of the DN MTL , DN CORE , and FPCN immediately before, during and subsequent to the onset of spontaneous thoughts.

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Reidler, J. S., Huang, C. & Buckner, R. L. Evidence for the default network's role in spontaneous cognition. J. Neurophysiol. 104 , 322–335 (2010).

Kucyi, A. & Davis, K. D. Dynamic functional connectivity of the default mode network tracks daydreaming. Neuroimage 100 , 471–480 (2014).

Foster, D. J. & Wilson, M. A. Reverse replay of behavioural sequences in hippocampal place cells during the awake state. Nature 440 , 680–683 (2006).

Karlsson, M. P. & Frank, L. M. Awake replay of remote experiences in the hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 12 , 913–918 (2009).

Carr, M. F., Jadhav, S. P. & Frank, L. M. Hippocampal replay in the awake state: a potential substrate for memory consolidation and retrieval. Nat. Neurosci. 14 , 147–153 (2011).

Dragoi, G. & Tonegawa, S. Distinct preplay of multiple novel spatial experiences in the rat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 9100–9105 (2013).

Dragoi, G. & Tonegawa, S. Preplay of future place cell sequences by hippocampal cellular assemblies. Nature 469 , 397–401 (2011).

Ólafsdóttir, H. F., Barry, C., Saleem, A. B. & Hassabis, D. Hippocampal place cells construct reward related sequences through unexplored space. eLife 4 , e06063 (2015).

Stark, C. E. L. & Clark, R. E. The medial temporal lobe. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27 , 279–306 (2004).

Moscovitch, M., Cabeza, R., Winocur, G. & Nadel, L. Episodic memory and beyond: the hippocampus and neocortex in transformation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67 , 105–134 (2016).

Romero, K. & Moscovitch, M. Episodic memory and event construction in aging and amnesia. J. Mem. Lang. 67 , 270–284 (2012).

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D. & Maguire, E. A. Using imagination to understand the neural basis of episodic memory. J. Neurosci. 27 , 14365–14374 (2007).

Buckner, R. L. The role of the hippocampus in prediction and imagination. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61 , 27–48 (2010).

Hassabis, D. & Maguire, E. A. The construction system of the brain. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364 , 1263–1271 (2009).

Schacter, D. L. et al. The future of memory: remembering, imagining, and the brain. Neuron 76 , 677–694 (2012).

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R. & Buckner, R. L. Episodic simulation of future events: concepts, data, and applications. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1124 , 39–60 (2008).

Moscovitch, M. Memory and working-with-memory: a component process model based on modules and central systems. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 4 , 257–267 (1992). This paper introduces the influential component process model of memory.

Teyler, T. J. & DiScenna, P. The hippocampal memory indexing theory. Behav. Neurosci. 100 , 147–154 (1986).

Moscovitch, M. The hippocampus as a “stupid,” domain-specific module: implications for theories of recent and remote memory, and of imagination. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 62 , 62–79 (2008).

Bar, M., Aminoff, E., Mason, M. & Fenske, M. The units of thought. Hippocampus 17 , 420–428 (2007). This paper introduces a novel hypothesis on the associative processes underlying a train of thoughts, originating in the MTL.

Aminoff, E. M., Kveraga, K. & Bar, M. The role of the parahippocampal cortex in cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 , 379–390 (2013).

Christoff, K., Keramatian, K., Gordon, A. M., Smith, R. & Mädler, B. Prefrontal organization of cognitive control according to levels of abstraction. Brain Res. 1286 , 94–105 (2009).

Dixon, M. L., Fox, K. C. R. & Christoff, K. Evidence for rostro-caudal functional organization in multiple brain areas related to goal-directed behavior. Brain Res. 1572 , 26–39 (2014).

McCaig, R. G., Dixon, M., Keramatian, K., Liu, I. & Christoff, K. Improved modulation of rostrolateral prefrontal cortex using real-time fMRI training and meta-cognitive awareness. Neuroimage 55 , 1298–1305 (2011).

Dixon, M. L. & Christoff, K. The decision to engage cognitive control is driven by expected reward-value: neural and behavioral evidence. PLoS ONE 7 , e51637 (2012).

Yin, H. H. & Knowlton, B. J. The role of the basal ganglia in habit formation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7 , 464–476 (2006).

Burguière. E., Monteiro, P., Mallet, L., Feng, G. & Graybiel, A. M. Striatal circuits, habits, and implications for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 30 , 59–65 (2015).

Mathews, A. & MacLeod, C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1 , 167–195 (2005).

Gotlib, I. H. & Joormann, J. Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 6 , 285–312 (2010).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E. & Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3 , 400–424 (2008).

Watkins, E. R. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychol. Bull. 134 , 163–206 (2008). This comprehensive review and theory article links the psychological literature on task-unrelated or stimulus-independent thought to the clinical literature on rumination and other forms of repetitive thought, proposing multiple factors that govern whether repetitive thought is constructive or unconstructive.

Giambra, L. M. & Traynor, T. D. Depression and daydreaming; an analysis based on self-ratings. J. Clin. Psychol. 34 , 14–25 (1978).

Larsen, R. J. & Cowan, G. S. Internal focus of attention and depression: a study of daily experience. Motiv. Emot. 12 , 237–249 (1988).

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Ford, J. M. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 8 , 49–76 (2012).

Anticevic, A. et al. The role of default network deactivation in cognition and disease. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 584–592 (2012).

Hamilton, J. P. et al. Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and new integration of baseline activation and neural response data. Am. J. Psychiatry 169 , 693–703 (2012).

Kaiser, R. H. et al. Distracted and down: neural mechanisms of affective interference in subclinical depression. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10 , 654–663 (2015).

Kaiser, R. H., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Wager, T. D. & Pizzagalli, D. A. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 72 , 603–637 (2015). This meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity studies in major depressive disorder provides quantitative support for functional-network imbalances, which reflect heightened internally focused thought in this disorder.

Kaiser, R. H. et al. Dynamic resting-state functional connectivity in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 41 , 1822–1830 (2015).

Spinhoven, P., Drost, J., van Hemert, B. & Penninx, B. W. Common rather than unique aspects of repetitive negative thinking are related to depressive and anxiety disorders and symptoms. J. Anxiety Disord. 33 , 45–52 (2015).

Borkovec, T. D., Ray, W. J. & Stober, J. Worry: a cognitive phenomenon intimately linked to affective, physiological, and interpersonal behavioral processes. Cognit. Ther. Res. 22 , 561–576 (1998).

Oathes, D. J., Patenaude, B., Schatzberg, A. F. & Etkin, A. Neurobiological signatures of anxiety and depression in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biol. Psychiatry 77 , 385–393 (2015).

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. & van IJzendoorn, M. H. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 133 , 1–24 (2007).

Williams, J., Watts, F. N., MacLeod, C. & Mathews, A. Cognitive Psychology and Emotional Disorders (John Wiley & Sons, 1997).

Etkin, A., Prater, K. E., Schatzberg, A. F., Menon, V. & Greicius, M. D. Disrupted amygdalar subregion functional connectivity and evidence of a compensatory network in generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66 , 1361–1372 (2009).

Ipser, J. C., Singh, L. & Stein, D. J. Meta-analysis of functional brain imaging in specific phobia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 67 , 311–322 (2013).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Boonstra, A. M., Oosterlaan, J., Sergeant, J. A. & Buitelaar, J. K. Executive functioning in adult ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Med. 35 , 1097–1108 (2005).

Willcutt, E. G., Doyle, A. E., Nigg, J. T., Faraone, S. V. & Pennington, B. F. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol. Psychiatry 57 , 1336–1346 (2005).

Kofler, M. J. et al. Reaction time variability in ADHD: a meta-analytic review of 319 studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33 , 795–811 (2013).

Shaw, G. A. & Giambra, L. Task unrelated thoughts of college students diagnosed as hyperactive in childhood. Dev. Neuropsychol. 9 , 17–30 (1993).

Franklin, M. S. et al. Tracking distraction: the relationship between mind-wandering, meta-awareness, and ADHD symptomatology. J. Atten. Disord. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1087054714543494 (2014).

De La Fuente, A., Xia, S., Branch, C. & Li, X. A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from the perspective of brain networks. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7 , 192 (2013).

Castellanos, F. X. & Proal, E. Large-scale brain systems in ADHD: beyond the prefrontal–striatal model. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 17–26 (2012).

Hart, H., Radua, J., Mataix-Cols, D. & Rubia, K. Meta-analysis of fMRI studies of timing in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36 , 2248–2256 (2012).

Hart, H., Radua, J., Nakao, T., Mataix-Cols, D. & Rubia, K. Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 70 , 185–198 (2013).

Fassbender, C. et al. A lack of default network suppression is linked to increased distractibility in ADHD. Brain Res. 1273 , 114–128 (2009).

Cortese, S. et al. Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 169 , 1038–1055 (2012).

Castellanos, F. X. et al. Cingulate-precuneus interactions: a new locus of dysfunction in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 63 , 332–337 (2008).

Uddin, L. Q. et al. Network homogeneity reveals decreased integrity of default-mode network in ADHD. J. Neurosci. Methods 169 , 249–254 (2008).

Tomasi, D. & Volkow, N. D. Abnormal functional connectivity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 71 , 443–450 (2012).

Mattfeld, A. T. et al. Brain differences between persistent and remitted attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Brain 137 , 2423–2428 (2014).

Sun, L. et al. Abnormal functional connectivity between the anterior cingulate and the default mode network in drug-naïve boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 201 , 120–127 (2012).

McCarthy, H. et al. Attention network hypoconnectivity with default and affective network hyperconnectivity in adults diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood. JAMA Psychiatry 70 , 1329–1337 (2013).

Fair, D. A. et al. The maturing architecture of the brain's default network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 , 4028–4032 (2008).

Sripada, C. et al. Disrupted network architecture of the resting brain in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35 , 4693–4705 (2014). By analysing data from more than 750 participants, this paper links childhood ADHD to abnormal resting-state functional connectivity involving the DN.

Fair, D. A. et al. Atypical default network connectivity in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 68 , 1084–1091 (2010).

Anderson, A. et al. Non-negative matrix factorization of multimodal MRI, fMRI and phenotypic data reveals differential changes in default mode subnetworks in ADHD. Neuroimage 102 , 207–219 (2014).

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59 , 2142–2154 (2012).

Van Dijk, K. R. A., Sabuncu, M. R. & Buckner, R. L. The influence of head motion on intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage 59 , 431–438 (2012).

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. & Castellanos, F. X. Spontaneous attentional fluctuations in impaired states and pathological conditions: a neurobiological hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 31 , 977–986 (2007).

Kerns, J. G. & Berenbaum, H. Cognitive impairments associated with formal thought disorder in people with schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 111 , 211–224 (2002).

Videbeck, S. L. Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006).

Hales, R. E., Yudofsky, S. C. & Roberts, L. W. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry 6th edn (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2014).

Haijma, S. V. et al. Brain volumes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis in over 18 000 subjects. Schizophr. Bull. 39 , 1129–1138 (2013).

Glahn, D. C. et al. Meta-analysis of gray matter anomalies in schizophrenia: application of anatomic likelihood estimation and network analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 64 , 774–781 (2008).

Fornito, A., Yücel, M., Patti, J., Wood, S. J. & Pantelis, C. Mapping grey matter reductions in schizophrenia: an anatomical likelihood estimation analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Schizophr. Res. 108 , 104–113 (2009).

Ellison-Wright, I. & Bullmore, E. Anatomy of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 117 , 1–12 (2010).

Vita, A., De Peri, L., Deste, G., Barlati, S. & Sacchetti, E. The effect of antipsychotic treatment on cortical gray matter changes in schizophrenia: does the class matter? A meta-analysis and meta-regression of longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol. Psychiatry 78 , 403–412 (2015).

Cole, M. W., Anticevic, A., Repovs, G. & Barch, D. Variable global dysconnectivity and individual differences in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 70 , 43–50 (2011).

Argyelan, M. et al. Resting-state fMRI connectivity impairment in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr. Bull. 40 , 100–110 (2014).

Cole, M. W., Yarkoni, T., Repovs, G., Anticevic, A. & Braver, T. S. Global connectivity of prefrontal cortex predicts cognitive control and intelligence. J. Neurosci. 32 , 8988–8999 (2012).

Baker, J. T. et al. Disruption of cortical association networks in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 71 , 109–110 (2014).

Karbasforoushan, H. & Woodward, N. D. Resting-state networks in schizophrenia. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 12 , 2404–2414 (2013).

Jafri, M. J., Pearlson, G. D., Stevens, M. & Calhoun, V. D. A method for functional network connectivity among spatially independent resting-state components in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 39 , 1666–1681 (2008).

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 , 1279–1284 (2009).

Palaniyappan, L., Simmonite, M., White, T. P., Liddle, E. B. & Liddle, P. F. Neural primacy of the salience processing system in schizophrenia. Neuron 79 , 814–828 (2013).

Mittner, M., Hawkins, G. E., Boekel, W. & Forstmann, B. U. A neural model of mind wandering. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20 , 570–578 (2016). This paper convincingly argues for the introduction of two important novel elements to the scientific study of mind-wandering: employing cognitive modelling and a consideration of neuromodulatory influences on thought.

Fox, K. C. R. & Christoff, K. in The Cognitive Neuroscience of Metacognition (eds Fleming, S. M. & Frith, C. D.) 293–319 (Springer, 2014).

Foulkes, D. & Fleisher, S. Mental activity in relaxed wakefulness. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 84 , 66–75 (1975).

Fox, K. C. R., Nijeboer, S., Solomonova, E., Domhoff, G. W. & Christoff, K. Dreaming as mind wandering: evidence from functional neuroimaging and first-person content reports. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7 , 412 (2013).

De Bono, E. Six Thinking Hats (Little Brown and Company, 1985).

Ellamil, M., Dobson, C., Beeman, M. & Christoff, K. Evaluative and generative modes of thought during the creative process. Neuroimage 59 , 1783–1794 (2012).

Beaty, R. E., Benedek, M., Kaufman, S. B. & Silvia, P. J. Default and executive network coupling supports creative idea production. Sci. Rep. 5 , 10964 (2015).

Fox, K. C. R., Kang, Y., Lifshitz, M. & Christoff, K. in Hypnosis and Meditation (eds Raz, A. & Lifshitz, M.) 191–210 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Fazelpour, S. & Thompson, E. The Kantian brain: brain dynamics from a neurophenomenological perspective. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 31 , 223–229 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to R. Buckner, P. Carruthers, M. Cuddy-Keane, M. Dixon, S. Fazelpour, D. Stan, E. Thompson, R. Todd and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback on earlier versions of this paper, and to A. Herrera-Bennett for help with the figure preparation. K.C. was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) (RGPIN 327317–11) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (MOP-115197). Z.C.I. was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) postdoctoral fellowship, the Balzan Styles of Reasoning Project and a Templeton Integrated Philosophy and Self Control grant. K.C.R.F. was supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. R.N.S. was supported by an Alzheimer's Association grant (NIRG-14-320049). J.R.A.-H. was supported by a Templeton Science of Prospection grant.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, 2136 West Mall, Vancouver, V6T 1Z4, British Columbia, Canada

Kalina Christoff & Kieran C. R. Fox

Centre for Brain Health, University of British Columbia, 2211 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, V6T 2B5, British Columbia, Canada

Kalina Christoff

Departments of Philosophy and Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, 94720, California, USA

Zachary C. Irving

Department of Human Development, Laboratory of Brain and Cognition, Cornell University,

R. Nathan Spreng

Human Neuroscience Institute, Cornell University, Ithaca, 14853, New York, USA

Institute of Cognitive Science, University of Colorado Boulder, UCB 594, Boulder, 80309–0594, Colorado, USA

Jessica R. Andrews-Hanna

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kalina Christoff .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

PowerPoint slides

Powerpoint slide for fig. 1, powerpoint slide for fig. 2, powerpoint slide for fig. 3, powerpoint slide for fig. 4, powerpoint slide for fig. 5.

A mental state, or a sequence of mental states, including the transitions that lead to each state.

A transient cognitive or emotional state of the organism that can be described in terms of its contents (what the state is 'about') and the relation that the subject bears to the contents (for example, perceiving, believing, fearing, imagining or remembering).

Thoughts with contents that are unrelated to what the person having those thoughts is currently doing.

Thinking that is characteristically fanciful (that is, divorced from physical or social reality); it can either be spontaneous, as in fanciful mind-wandering, or constrained, as during deliberately fantasizing about a topic.

A thought with contents that are unrelated to the current external perceptual environment.

A deliberate guidance of current thoughts, perceptions or actions, which is imposed in a goal-directed manner by currently active top-down executive processes.

The emotional significance of percepts, thoughts or other elements of mental experience, which can draw and sustain attention through mechanisms outside of cognitive control.

Features of current perceptual experience, such as high perceptual contrast, which can draw and sustain attention through mechanisms outside of cognitive control.

The process of spontaneously or deliberately inferring one's own or other agents' mental states.

Flexible combinations of distinct elements of prior experiences, constructed in the process of imagining a novel (often future-oriented) event.

A type of dreaming during which the dreamer is aware that he or she is currently dreaming and, in some cases, can have deliberate control over dream content and progression.

The ability to produce ideas that are both novel (that is, original and unique) and useful (that is, appropriate and meaningful).

A method in which participants are probed at random intervals and asked to report on aspects of their subjective experience immediately before the probe.

Different ways of categorizing a thought based on its contents, including stimulus dependence (whether the thought is about stimuli that one is currently perceiving), task relatedness (whether the thought is about the current task), modality (visual, auditory, and so on), valence (whether the thought is negative, neutral or positive) or temporal orientation (whether the thought is about the past, present or future).

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Christoff, K., Irving, Z., Fox, K. et al. Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: a dynamic framework. Nat Rev Neurosci 17 , 718–731 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.113

Download citation

Published : 22 September 2016

Issue Date : November 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.113

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Evidence synthesis indicates contentless experiences in meditation are neither truly contentless nor identical.

- Toby J. Woods

- Jennifer M. Windt

- Olivia Carter

Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences (2024)

The mediating role of default mode network during meaning-making aroused by mental simulation between stressful events and stress-related growth: a task fMRI study

Behavioral and Brain Functions (2023)

The role of memory in creative ideation

- Mathias Benedek

- Roger E. Beaty

- Yoed N. Kenett

Nature Reviews Psychology (2023)

A tripartite view of the posterior cingulate cortex

- Brett L. Foster

- Seth R. Koslov

- Sarah R. Heilbronner

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2023)

Effect of subconscious changes in bodily response on thought shifting in people with accurate interoception

- Mai Sakuragi

- Kazushi Shinagawa

- Satoshi Umeda

Scientific Reports (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

The Wandering Mind: How the Brain Allows Us to Mentally Wander Off to Another Time and Place

A unique human characteristic is our ability to mind wander—these are periods of time when our attention drifts away from the task-at-hand to focus on thoughts that are unrelated to the task. Mind wandering has some benefits, such as increased creativity, but it also has some negative consequences, such as mistakes in the task we are supposed to be performing. Interestingly, we spend up to half of our waking hours mind wandering. How does the brain help us accomplish that? Research suggests that when we mind wander, our responses to information from the external world around us are disrupted. In other words, our brain’s resources are shifted away from processing information from the external environment and redirected to our internal world, which allows us to mentally wander off to another time and place. Even though we pay less attention to the external world during mind wandering, our ability to detect unexpected events in our surrounding environment is preserved. This suggests that we are quite clever about what we ignore or pay attention to in the external environment, even when we mind wander.

How Do Scientists Define Mind Wandering?

Imagine this: you are sitting in a classroom on a sunny day as your science teacher enthusiastically tells you what our brain is capable of doing. Initially, you pay close attention to what the teacher is saying. But the sound of the words coming out of her mouth gradually fade away as you notice your stomach growling and you begin to think about that delicious ice cream you had last night. Have you ever caught yourself mind wandering in similar situations, where your eyes are fixed on your teacher, friends, or parents, but your mind has secretly wandered off to another time and place? You may be recalling the last sports game you watched, or fantasizing about going to the new amusement park this upcoming weekend, or humming your favorite tune that you just cannot get out of your head. This experience is what scientists call mind wandering, which is a period of time when we are focused on things that are not related to the ongoing task or what is actually going on around us (as shown in Figure 1 ).

- Figure 1 - Real-world example of on-task and mind wandering states among students in a classroom.

- In a science class in which the teacher asks a question about the brain, some students may be focused on what is being taught, while others may be thinking about yesterday’s basketball tournament, humming their favorite tune, or thinking about getting ice cream after school. The students thinking about the brain during class would be considered to be “on task,” while students thinking about things unrelated to the brain would be considered to be “mind wandering.”

Our Tendency to Mind Wander

Humans on average spend up to half of their waking hours mind wandering. There are differences across individuals in their tendency to mind wander and many factors that affect this tendency. For instance, older adults on average tend to mind wander less than younger adults. Also, individuals who are often sad or worried mind wander more frequently compared with individuals who are happy and have nothing to worry about. We also mind wander more when we perform tasks that we are used to doing, compared with when we perform novel and challenging tasks. There are also different types of mind wandering. For example, we may sometimes mind wander on purpose when we are bored with what we are currently doing. Other times, our mind accidentally wanders off without us noticing.

What are the Pros and Cons of Mind Wandering?

Since we spend so much time mind wandering, does this mean that mind wandering is good for us or not? There are certainly benefits to mind wandering. For example, one of the things the mind does when it wanders is to make plans about the future. In fact, we are more likely to make plans when we mind wander than we are to fantasize about unrealistic situations. Planning ahead is a good use of time as it allows us to efficiently carry out our day-to-day tasks, such as finishing homework, practicing soccer, and preparing for a performance. When mind wandering, we are also likely to reflect upon ourselves. This process of thinking about how we think, behave, and interact with others around us is a crucial part of our self-identity. Mind wandering has also been tied to creative problem-solving. There are times when we get stuck on a challenging math problem or feel uninspired to paint or make music, and research suggests that taking a break from thinking about these problems and letting the mind wander off to another topic may eventually lead to an “aha” moment, in which we come up with a creative solution or idea.

However, mind wandering can also have negative outcomes. For example, mind wandering in class means you miss out on what is being taught, and mind wandering while doing your homework may result in mistakes. Taken to an extreme, people who are diagnosed with depression constantly engage in their own thoughts about their problems or other negative experiences. In contrast, individuals diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who continually change their focus of attention may have a hard time completing a task. Taken together, whether mind wandering is good or bad depends on when we mind wander and what we mind wander about [ 1 ].

Scientific Measures of Mind Wandering

If you were to conduct an experiment, how would you measure mind wandering? Scientists have come up with several methods, one of which is called experience sampling . As research volunteers are doing a computer task in a laboratory, or as they are doing chores in their day-to-day lives, they are asked at random intervals to report their attention state. That is, they have to stop what they are doing and ask themselves what they were thinking about in the moment: “Was I on-task?” (that is, was I paying attention to the task-at-hand) or “Was I mind wandering?” (that is, did my mind wander off to another time and place). Therefore, experience sampling samples the volunteer’s in-the-moment experience, allowing scientists to understand how frequently people mind wander and how mind wandering affects the way people interact with their environments.

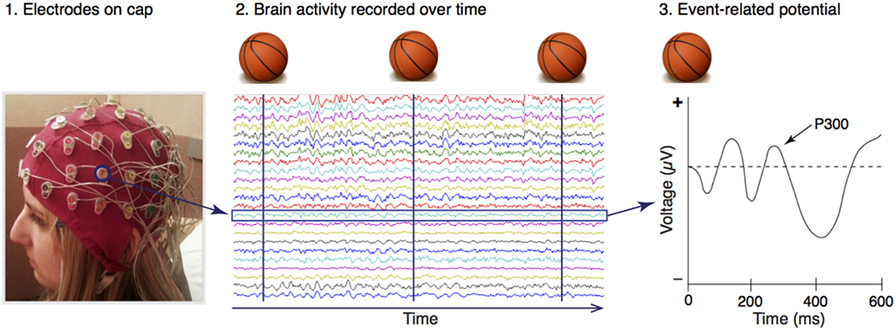

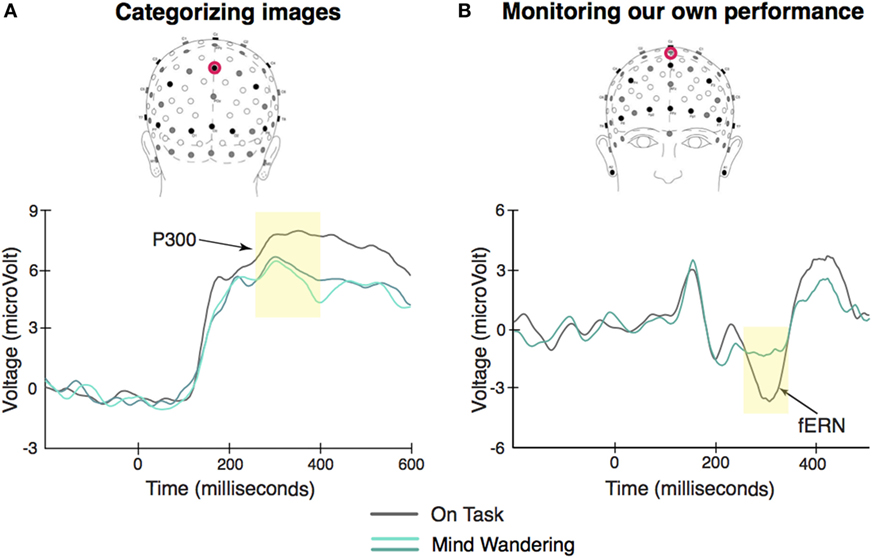

Scientists also study mind wandering by recording electroencephalogram (EEG) , a test that measures the electrical activity of the brain. This electrical activity, which looks like wavy lines during an EEG recording (see Figure 2 , Step 2), is observed in all parts of the brain and is present throughout the day, even when we are asleep. Measurements of the brain’s electrical activity help scientists understand how the brain allows us to think, speak, move, and do all the fun and creative and challenging things that we do! In order to record EEG, scientists place special sensors called electrodes on the scalp of a volunteer ( Figure 2 , Step 1), with each electrode recording activity of numerous neurons (brain cells) in the area under the electrode ( Figure 2 , Step 2). Scientists then examine the brain’s activity in response to images (such as a picture of a basketball in Figure 2 ) or sounds presented to the volunteer. The scientists present the same sound or picture to the volunteer multiple times and take the average of the brain’s activity in response to the image or sound, because that method results in a better EEG signal. The averaged brain activity produces something called an event-related potential (ERP) waveform that contains several high and low points, called peaks and troughs ( Figure 2 , Step 3), which represent the brain’s response to the image or sound over time. Some commonly seen peaks and troughs are assigned specific names as ERP components. For instance, a peak that occurs around 300 ms (only 3/10 of a second!) following the presentation of a picture or a sound is often called the P300 ERP component. Based on decades of research, scientists have shown that these ERP components reflect our brain’s response to events we see or hear. The size of the ERP components (measured in voltage) reflects how strong the response is, while the timing of these ERP components (measured in milliseconds) reflects the timing of the response. Now, PAUSE! I would like you to ask yourself, “Was I paying full attention to the previous sentence just now, or was I thinking about something else?” This is an example of experience sampling. And as you may realize now, when we are asked about our current attention state, we can quite accurately report it.

- Figure 2 - Recording electroencephalogram (EEG) in humans.

- Step 1. To record EEG, electrodes are attached to a cap that is placed on the scalp of a research volunteer. Step 2. Each wavy line represents the amount of activity recorded by each electrode. Research volunteers are usually presented with some images (e.g., a basketball) or sounds a number of times while their brain activity is being recorded. Step 3. Scientists calculate the average EEG activity across multiple presentations of the same picture/sound. This results in an Event-Related Potential (ERP) waveform, where time (in milliseconds) is plotted on the x-axis and the voltage (in microvolts, indicating the size of the ERP components) is plotted on the y-axis. On the x-axis, 0 indicates the time at which the stimulus (e.g., image of a basketball) was presented. The ERP waveforms contain multiple high and low points, called peaks and troughs. Some of the peaks and troughs are given specific labels. For example, the peak that occurs around 300 ms after an image is presented is often called the P300 ERP component.

What Happens to Our Interaction with the Environment When We Mind Wander?

Scientists have proposed an idea—called the “Decoupling Hypothesis”—stating that during mind wandering, the brain’s resources are shifted away from our surrounding environment and are redirected to our internal world in order to support our thoughts [ 2 ]. This hypothesis assumes that the brain has a certain amount of resources, which means that once mind wandering has used the resources it needs to focus on our thoughts, only a limited amount of brain resources remains for responding to our surrounding environment.

To test this hypothesis, scientists combined experience sampling with EEG to explore how mind wandering affects our interaction with the environment. One of the first studies to test this hypothesis asked research volunteers to categorize a series of images by responding whenever they saw rare targets (e.g., images of soccer balls) among a whole bunch of non-targets (e.g., images of basketballs). Throughout the task, EEG was recorded from the volunteers, and they were also asked at random times to report their attention state as “on task” or “mind wandering.” Based on their EEGs and experience sampling reports, scientists found that the brain’s response to the non-targets was reduced during periods of mind wandering compared with periods of being on task [ 3 ]. This can be seen in Figure 3A , where there is a smaller P300 ERP component during mind wandering (the green lines) compared with the P300 ERP component during the time when the volunteer was on task (the gray line). The data suggest that the brain’s response to events happening in our environment is disrupted when we engage in mind wandering.

- Figure 3 - Mind wandering affects our ability to process events in the environment.

- A. The brain’s processing of external events (e.g., images of basketballs and soccer balls) is reduced during periods of mind wandering. This is indicated by the smaller P300 ERP component during mind wandering (green lines) compared with on-task (gray line). The ERP waveform was recorded from the electrode site circled in red, which is located on the back of the head. B. Mind wandering impairs our ability to monitor our own performance, making it more likely that we will make mistakes. This is shown by the smaller feedback error-related negativity ERP component, a trough occurring around 250 ms, for mind wandering (green line) compared with on-task (gray line). The ERP waveform was recorded from the electrode site circled in red, which is located near the front of the head.

Have you ever noticed that if your mind wanders while you are doing homework, you are more likely to make mistakes? Many experiments have also shown that this happens! This led some scientists to question what is happening in the brain when we make mistakes. They specifically measured something called the feedback error-related negativity ERP component, which gives scientists an idea of how closely we are monitoring the accuracy of our responses when we perform a task. The scientists found that the feedback error-related negativity ERP component was reduced during mind wandering compared with on-task periods, as shown in Figure 3B . This suggests that mind wandering negatively affects our ability to monitor our performance and adjust our behavior, making it more likely that we will make mistakes [ 4 ]. All of these studies provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that when the mind wanders, our responses to what is going on in the environment around us are disrupted.

Does Mind Wandering Impair all Responses to the Environment?

At this point, you may wonder: are all responses to the world around us impaired during mind wandering? This seems unlikely, because we are usually quite capable of responding to the external environment even when we mind wander. For example, even though we may mind wander a lot while walking, most of us rarely bump into things as we walk from place to place. A group of scientists asked the same question and looked specifically at whether we can still pay attention to our environment at some level even when we are mind wandering. To test this question, research volunteers were asked to read a book while they were listening to some tones unrelated to the book. Most of the tones were identical, but among these identical tones was rare and different tone that naturally grabbed the attention of the volunteers. These scientists found that the volunteers paid just as much attention to this rare tone when they were mind wandering compared to when they were on task. In other words, our minds appear to be quite smart about which attention processes to disrupt and which processes to preserve during mind wandering. Under normal circumstances, our minds ignore some of the ordinary events in our environment in order for us to maintain a train of thought. However, when an unexpected event occurs in the environment, one that is potentially dangerous, our brain knows to shift our attention to the external environment so that we can respond to the potentially dangerous event. Imagine walking down the street and thinking about the movie you want to watch this weekend. While doing this, you may not clearly perceive the noise of the car engines or the pedestrians chatting around you. However, if a car suddenly honks loudly, you will hear the honk immediately, which will snap you out of your mind wandering. Therefore, even when the mind is wandering, we are still clever about what we ignore and what we pay attention to in the external environment, allowing us to smartly respond to the unusual, or potentially dangerous, events that may require us to focus our attention back on the external environment.

In summary, the brain appears to support mind wandering by disrupting some of the brain processes that are involved in responding to our surrounding external environment. This ability is important for protecting our thoughts from external distractions and allowing us to fully engage in mind wandering. We are only beginning to understand this mysterious experience of thinking, and scientists are actively researching what goes on in the brain when we mind wander. Increasing our knowledge about mind wandering will help us better understand how to take advantage of its benefits while avoiding the problems linked to mind wandering.

Mind Wandering : ↑ Periods of time when an individual is thinking of something that is unrelated to the task he/she is performing.

Experience Sampling : ↑ A scientific method in which a person is asked to report their experience; that is, whether he or she is paying attention or mind wandering at random intervals in the laboratory setting or in the real world.

Electroenceph-Alogram (EEG—“elec-tro-en-sef-a-lo-gram”) : ↑ Electrical activity of many neurons in the brain that is measured by electrodes placed on the scalp.

Event-Related Potential (ERPs) : ↑ Peaks or troughs in the averaged EEG signal that reflect the brain’s responses to events we see or hear.

P300 : ↑ An ERP component that typically peaks around 300 ms (therefore “300”) after a person sees a picture or hears a sound. It reflects the brain’s processing of the information that is seen or heard. an ERP component that typically peaks around 300 ms (therefore “300”) after a person sees a picture or hears a sound. It reflects the brain’s processing of the information that is seen or heard.

Feedback Error-Related Negativity : ↑ An ERP component that reflects how much a person is monitoring the accuracy of his/her performance.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

[1] ↑ Smallwood, J., and Andrews-Hanna, J. 2013. Not all minds that wander are lost: the importance of a balanced perspective on the mind-wandering state. Front. Psychol. 4:441. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00441

[2] ↑ Smallwood, J. 2013. Distinguishing how from why the mind wanders: a process-occurrence framework for self-generated mental activity. Psychol. Bull. 139(2013):519–35. doi:10.1037/a0030010

[3] ↑ Smallwood, J., Beach, E., Schooler, J. W., and Handy, T. C. 2008. Going AWOL in the brain: mind wandering cortical analysis of external events. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20:458–69. doi:10.1162/jocn.2008.20037

[4] ↑ Kam, J. W. Y., Dao, E., Blinn, P., Krigolson, O. E., Boyd, L. A., and Handy, T. C. 2012. Mind wandering and motor control: off-task thinking disrupts the online adjustment of behavior. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:329. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00329

How to Tame Your Wandering Mind

Learn to take steps to deal with distraction..

Posted April 24, 2022 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

- Understanding Attention

- Find counselling to help with ADHD

- We can tame our mind-wandering.

- Three tips can help you use mind-wandering to your advantage.

- These include making time to mind-wander and controlling your response to it.

Researchers believe that when a task isn’t sufficiently rewarding, our brains search for something more interesting to think about.

You have a big deadline looming, and it’s time to hunker down. But every time you start working, you find that, for some reason, your mind drifts off before you can get any real work done. What gives? What is this cruel trick our brains play on us, and what do we do about it?

Thankfully, by understanding why our mind wanders and taking steps to deal with distraction, we can stay on track. But first, let’s understand the root of the problem.

Why do our minds wander?

Unintentional mind-wandering occurs when our thoughts are not tied to the task at hand. Researchers believe our minds wander when the thing we’re supposed to be doing is not sufficiently rewarding, so our brains look for something more interesting to think about.

We’ve all experienced it from time to time, but it’s important to note that some people struggle with chronic mind-wandering : Though studies estimate ADHD afflicts less than 3% of the global adult population, it can be a serious problem and may require medical intervention.

For the vast majority of people, mind-wandering is something we can tame on our own—that is, if we know what to do about it. In fact, according to Professor Ethan Kross, director of the Emotion & Self Control Laboratory at the University of Michigan and author of Chatter: The Voice in Our Head, Why It Matters, and How to Harness It , mind-wandering is perfectly normal.

“We spend between a third to a half of our waking hours not focused on the present,” he told me in an email. “Some neuroscience research refers to our tendency to mind-wander as our ‘default state.’”

So why do we do it?

“Mind-wandering serves several valuable functions. It helps us simulate and plan for the future and learn from our past, and it facilitates creative problem-solving,” Kross explained. “Mind-wandering often gets a bad rep, but it’s a psychological process that evolved to provide us with a competitive advantage. Imagine not being able to plan for the future or learn from your past mistakes.”

Is mind-wandering bad for you?

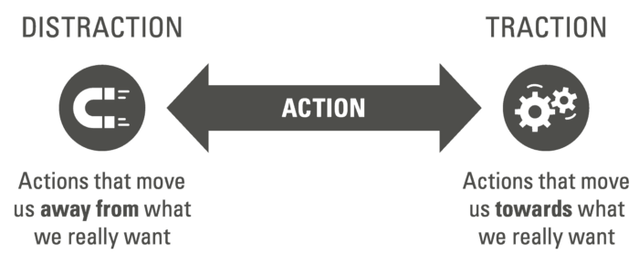

“Like any psychological tool, however, mind-wandering can be harmful if used in the wrong context (i.e., when you’re trying to focus on a task) or inappropriately (i.e., when you worry or ruminate too much),” according to Kross. In other words, mind-wandering is a problem when it becomes a distraction. A distraction is any action that pulls you away from what you planned to do.

If, for instance, you intended to work on a big project, such as writing a blog post or finishing a proposal, but instead find yourself doing something else, you’re distracted.

The good news is that we can use mind-wandering to our advantage if we follow a few simple steps:

1. Make time to mind-wander

Mind-wandering isn’t always a distraction. If we plan for it, we can turn mind-wandering into traction. Unlike a distraction , which by definition is a bad thing, a diversion is simply a refocusing of attention and isn’t always harmful.

There’s nothing wrong with deciding to refocus your attention for a while. In fact, we often enjoy all kinds of diversions and pay for the privilege.

A movie or a good book, for instance, diverts our attention away from real life for a while so we can get into the story and escape reality for a bit.

Similarly, if you make time to allow your mind to drift and explore whatever it likes, that’s a healthy diversion, not a distraction.

The first step to mastering mind-wandering is to plan time for it. Use a schedule maker and block off time in your day to let your thoughts flow freely. You’ll likely find that a few minutes spent in contemplation can help you work through unresolved issues and lead to breakthroughs. Scheduling mind-wandering also lets you relax because you know you have time to think about whatever is on your mind instead of believing you need to act on every passing thought.

It’s helpful to know that time to think is on your calendar so you don’t have to interrupt your mind-wandering process or risk getting distracted later.

2. Catch the action

One of the difficulties surrounding mind-wandering is that by the time you notice you’re doing it, you’ve already done it. It’s an unconscious process so you can’t prevent it from happening.

The good news is that while you can’t stop your mind from wandering, you can control what you do when it happens.

Many people never learn that they are not their thoughts. They believe the voice in their head is somehow a special part of them, like their soul speaking out their inner desires and true self. When random thoughts cross their mind, they think those thoughts must be speaking some important truth.

Not true. That voice in your head is not your soul talking, nor do you have to believe everything you think.

When we assign undue importance to the chatter in our heads, we risk listening to half-baked ideas, feeling shame for intrusive thoughts, or acting impulsively against our best interests.

A much healthier way to view mind-wandering is as brain static. Just as the random radio frequencies you tune through don’t reveal the inner desires of your car’s soul, the thoughts you have while mind-wandering don’t mean much—unless, that is, you act upon them.

Though it can throw us off track, mind-wandering generally only lasts a few seconds, maybe minutes. However, when we let mind-wandering turn into other distractions, such as social-media scrolling, television-channel surfing, or news-headline checking, that’s when we risk wasting hours rather than mere minutes.

If you do find yourself mentally drifting off in the middle of a task, the important thing is to not allow that to become an unintended action, and therefore a distraction.

An intrusive thought is not your fault. It can’t be controlled. What matters is how you respond to it—hence the word respon-sibility.

Do you let the thought go and stay on task? Or do you allow yourself to escape what you’re doing by letting it lead you toward an action you’ll later regret?

3. Note and refocus

Can we keep the helpful aspects of mind-wandering while doing away with the bad? For the most part, yes, we can.

According to Kross, “Mind-wandering can easily shift into dysfunctional worry and rumination. When that happens, the options are to refocus on the present or to implement tools that help people mind-wander more effectively.”

One of the best ways to harness the power of mind-wandering while doing an important task is to quickly note the thought you don’t want to lose on a piece of paper. It’s a simple tactic anyone can use but few bother to do. Note that I didn’t recommend an app or sending yourself an email. Tech tools are full of external triggers that can tempt us to just check “one quick thing,” and before we know it, we’re distracted.

Rather, a pen and Post-it note or a notepad are the ideal tools to get ideas out of your head without the temptations that may lead you away from what you planned to do.

Then, you can collect your thoughts and check back on them later during the time you’ve planned in your day to chew on your ideas. If you give your thoughts a little time, you’ll often find that those super important ideas aren’t so important after all.

If you had acted on them at the moment, they would have wasted your time. But by writing them down and revisiting them when you’ve planned to do so, they have time to marinate and may become less relevant.

However, once in a while, an idea you collected will turn out to be a gem. With the time you planned to chew on the thought, you may discover that mind-wandering spurred you to a great insight you can explore later.

By following the three steps above, you’ll be able to master mind-wandering rather than letting it become your master.

Nir Eyal, who has lectured at Stanford's Graduate School of Business and the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, is the author of Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Support Group

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology