Sign up to get the latest WWF news delivered straight to your inbox

Top 10 facts about Jaguars

1. They have a mighty name

The word 'jaguar' comes from the indigenous word 'yaguar', which means 'he who kills with one leap'. You’ll find out why later...

2. Their territory is shrinking

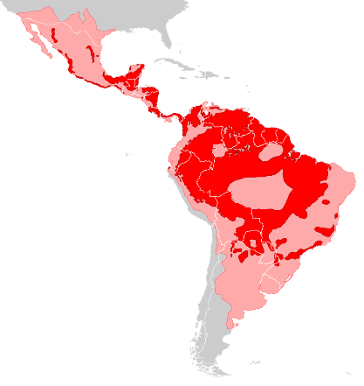

Jaguars used to be found from the south-west USA, throughout South America to the central-southern part of Argentina. Now, they’ve been virtually eliminated from half of their historic range.

There are around 173,000 jaguars left in the world today, and most of these big cats are found in the Amazon rainforest and the Pantanal, the largest tropical wetland. Their stronghold is in Brazil – it may hold around half of the estimated wild numbers.

3. They’re on the chunky side

The jaguar is the third biggest cat in the world - after the tiger and the lion - and is the largest cat in the Americas. They can grow up to 170cm long, not including their impressive tails which can be up to 80cm.

Male jaguars can weigh 120kg (that’s almost 19 stone), while female jaguars can weigh much less, up to 100kg. But their sizes can vary a lot between regions - jaguars in central America can be roughly half the size of jaguars in the Pantanal. They need that bulk behind them to take on big prey, including giant caiman.

4. They’ve got spotty spots

To the untrained eye, jaguars can be mistaken for leopards as they look similar, but you can tell the difference from their rosettes (circular markings): Jaguars have black dots in the middle of some of their rosettes, whereas leopards don’t. Jaguars also have larger, rounded heads and short legs.

Jaguars can be “melanistic", where they appear almost as if they are black jaguars. However, this is a commonly misidentified term as melanistic jaguars (and leopards) are known as “black panthers”.

5. Jaguars are excellent swimmers

Unlike many domestic cats, jaguars don’t avoid water. They have adapted to living in wet environments, and can be found swimming in lakes, rivers and wetlands. They are confident swimmers, known to cross large rivers.

6. Jaguars roar

Both males and females roar, which helps bring them together when they want to mate.

A jaguar's usual call is called a 'saw' because it sounds like the sawing of wood - but with the saw only moving in one direction.

When jaguars greet each other, or reassure one another, they make a noise like a nasally snuffling.

7. They’ll eat almost anything

Jaguars are opportunistic hunters and can prey upon almost anything they come across. Capybaras, deer, tortoises, iguanas, armadillos, fish, birds and monkeys are just some of the prey that jaguars eat. They can even tackle South America’s largest animal, the tapir, and huge predators like caiman.

Jaguars are nocturnal as well as diurnal big cats. They hunt both in the day and at night, traveling long distances.

8. They kill with a powerful bite

Jaguars have a more powerful bite than any other big cat. Their teeth are strong enough to bite through the thick hides of crocodilians and the hard shells of turtles.

They need powerful teeth and jaws to take down prey three to four times their own weight - usually killing it with a bite to the back of the skull rather than biting the neck or throat like other big cats.

Like other cats, their tongues have sharp-pointed bumps, called papillae, which are used to scrape meat off bones.

9. Their cubs grow quickly

When breeding, a pair of jaguars may mate up to 100 times a day. That’s exhausting.

Pregnancy lasts around 14 weeks, then the female usually gives birth to two jaguar cubs (though she can have up to four).

Jaguar cubs weigh about the same as a loaf of bread when they’re born, but they soon grow. At two years old, males can be 50% heavier than their female siblings.

10. Jaguars face growing threats

Deforestation rates are high in Latin America, both for logging and to clear space for cattle ranching. This results in many new threats to jaguars, from the loss of their home to isolating their populations, making breeding harder. Less habitat also means jaguars’ prey is reduced - over a quarter of their range is thought to have depleted numbers of wild prey. This leads them to hunt livestock and be killed by people.

They’re also vulnerable to poaching, despite this being illegal. Though demand for their skins has declined since the mid-1970s, jaguar paws, teeth and other parts are still sought after, both locally and internationally for traditional medicine and ornaments.

We've worked in the Amazon for over 40 years - creating and managing protected areas of habitat, working with local communities to monitor jaguars, working with cattle ranchers to improve existing ranches and prevent new deforestation, and promoting sustainable development that has minimal impact on vital jaguar habitat.

We’re also working with partners to help prevent the demand, poaching and trafficking of jaguars and other species.

Help us keep this unique bear thriving – adopt a giant panda now.

Watch our YouTube video about Jaguars

12 Fierce Facts About Jaguars

From their strong bite to their love of water, learn all about these amazing big cats.

- Chapman University

- Animal Rights

- Endangered Species

Jaguars , known for their distinctive yellow-orange fur and unique spots, are found in small pockets of forested habitats throughout South, North, and Central America. Designated as “Near Threatened” by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species , they are the largest cats in the Americas and also the only living representative of the genus Panthera.

It was much easier to find these big cats a century ago when their territory extended as far north as New Mexico and Arizona in the United States and as far south as Argentina. Due to threats like deforestation and habitat degradation, however, they’ve lost 46% of their historic range. Today, the majority of jaguar populations are condensed to the Amazon basin and are continuing to decrease.

Here are a few facts you may not have known about the elusive jaguar.

- Common Name : Jaguar

- Scientific Name : Panthera onca

- Average Lifespan in the Wild : 12 to 15 years

- Average Lifespan in Captivity : Up to 20 years

- IUCN Red List Status : Near Threatened

1. Jaguars Have the Strongest Bite of the Cat Kingdom (Relative to Size)

These majestic cats have a stocky, heavy build with robust canines and a massive head, allowing them a more powerful bite than any other large cat relative to its size. Studies comparing the bite forces of nine different cat species revealed that, while a jaguar’s bite force is only three-quarters as strong as a tiger’s bite force, jaguars have the stronger bites since they are considerably smaller (up to 170 cm long, not including their tails, which can grow up to 80 cm). A jaguar’s jaw can bite straight through the skull of its prey, and can even pierce the thick skin of a caiman with ease.

2. They Love the Water

Unlike most cats, Jaguars don’t mind getting wet. They are very strong swimmers and their habitat is usually characterized by the presence of water bodies. Jaguars also need dense forest cover and a sufficient prey base in order to survive, but on occasion are also found in swamp areas, grasslands, and even dry scrub woodlands. Out of all the big cat species, jaguars are the most commonly associated with water.

3. Male Territories Are Twice the Size of Female Territories

In Mexico, male jaguars maintain an annual home range of about 100 square kilometers, while females occupy around 46 square kilometers. Males also cover more ground within a 24-hour period, about 2,600 meters to the female's 2,000 meters during the dry season. Males put more time into marking territory and defending their home ranges against other males, using methods like vocalization, scraping trees, and scent marking.

4. Jaguars Are Loners

Jaguars tend to roam their land by themselves, marking their territory to let other jaguars know what is theirs. Female jaguars raise their cubs by themselves, and the young jaguars begin to hunt on their own at around two years old.

5. They’re Often Mistaken for Leopards

Jaguars and leopards are often mistaken because they are both tawny-colored, spotted, big cats. The most obvious difference between the two is in the spots, or rosettes. If you look closely, jaguar spots are actually more fragmented and encircle smaller spots. Scientists believe that these spots help break up their outlines in the dense forest or grass, giving them more opportunities to hide from their prey. Jaguars also have a stockier build with shorter legs, a broad head, and hail from the Americas, while leopards are found in Africa and Asia.

6. Jaguars Hunt During Both Day and Night

Jaguars tend to be solitary creatures, living an elusive lifestyle that is both diurnal and nocturnal. Thanks to their night vision, jaguars are able to sneak up on their nocturnal prey armed with incredibly strong jaws and built-in camouflaging spots. A 2010 study found that in Belize, 70% of jaguar activity occurred at night, while in Venezuela it was anywhere from 40% to 60%.

7. They’ve Inspired Myths and Legends

Spending their lives stalking the forests of the Americas with their sleek, mysterious frame, it's no wonder that the jaguar has earned a prominent place in mythology and legend. In the Tupi-Guarani languages of South America, jaguar comes from the word "yaguara," which translates into “wild beast that overcomes its prey in a bound.” While references to jaguars throughout history in South America have been well documented, the cats also have a lesser known place in prehistoric Native American cultures such as the Pueblo, Southern Athabaskan, and Northern Pima tribes of the American Southwest.

8. They Roar

Lions, tigers, and jaguars have an elastic ligament called an epihyoideum behind their nose and mouth instead of a bony element like a domestic cat, giving them the ability to roar but not purr.

A male jaguar roar is louder than a female's—as females have softer vocalizations unless they are in heat—but the two call and respond to each other using a specific series of calls during mating season. Sadly, this is often taken advantage of by poachers, who have developed methods to mimic the unique call.

9. They Are Opportunistic Hunters

Jaguars will eat almost anything. They have a wide variety of prey species including mammals, reptiles, and birds (both wild and livestock). Mostly hunting on the ground, they have also been known to climb trees and jump on their prey from above. It is estimated that 50% of their kills are larger prey, consumed over four days, which they do in order to preserve energy.

10. Jaguars' Tongues Help Them Eat

Aside from their incredibly strong bite, jaguars have rough tongues with spiny papillae that help them consume meat and lick the bones of their prey. Papillae also allow them to adequately clean themselves.

11. Black Jaguars Are Common

The result of a single dominant allele, about 10% of jaguars have evolved to have black (or melanistic) coats, though scientists aren't completely sure why. A study in 2020 found that 25% of the jaguars that lived in dense forests in Costa Rica were melanistic, much more than the global average, suggesting that the mutation occurs due to camouflage advantages.

The study also found that black jaguars were more active during the full moon. While from a distance it may seem like these jaguars are completely black in color, they actually have a base coat of black fur with dark black spots that are more visible from certain angles.

Fun fact: In big cats, the black panther is not a distinct species but rather a general name used to refer to any black-colored member of the Panthera animal group name, usually leopards, jaguars, and mountain lions.

12. They’ve Already Lost Half of Their Historic Range

Historically, the jaguar ranged from the southwestern United States and the Mexican border through the Amazon basin and into the Rio Negro of Argentina. Today, jaguars have been virtually eliminated from most of the northern regions such as Arizona and New Mexico, as well as Sonora state in Mexico, northern Brazil, Uruguay, and the grasslands of Argentina.

The IUCN found that jaguars occupied only about 46% of their historic range in 2002, and by 2008 that number was estimated to have grown to 51%. The Amazon basin rainforest currently holds 57% of the global jaguar population. Remote wildlife cameras in Arizona have documented several jaguars periodically from 2011 to 2017, notably three males named “Macho B,” “El Jefe,” and “Sombra.”

Save the Jaguar

- Support anti-poaching legislation by signing petitions and spreading the word about threats to jaguars.

- Donate to the organizations that support global conservation work, such as the World Wildlife Fund's symbolic jaguar adoption program.

- Contribute to the conservation of jaguar forest habitats, especially the Amazon, by purchasing products that have been sustainably sourced. For example, look for the FSC-certified label on your wood products.

Sanderson, Eric W., et al. “ Planning to Save a Species: The Jaguar as a Model .” Conservation Biology , vol. 16, 2002, pp. 58-72.,doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00352.x

Hartstone-Rose, Adam, et al. “ Bite Force Estimation and the Fiber Architecture of Felid Masticatory Muscles .” Anat Rec, vol. 295, 2012, pp. 1336-1351., doi:10.1002/ar.22518

Quigley, H., et al. “ Panthera Onca (Errata Version Published in 2018) .” The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017 , 2017, doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15953A50658693.en

Nuñez-Perez, Rodrigo, and Brian Miller B. “ Movements and Home Range of Jaguars (Panthera onca) and Mountain Lions (Puma concolor) in a Tropical Dry Forest of Western Mexico .” In: Reyna-Hurtado R., and C. Chapman (eds) Movement Ecology of Neotropical Forest Mammals. Springer, 2019, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-03463-4_14

Jaguar . San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

Dougoud, Michael, et al. “ The Phenomenon of Growing Surface Interference Explains the Rosette Pattern of Jaguar .” Tissues and Organs, 2017.

Harmsen, Bart J., et al. “ Jaguar and Puma Activity Patterns in Relation to Their Main Prey .” Mammalian Biology , vol. 76, 2011, pp. 320-324., doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2010.08.007

Hayward, Matt W., et al. “ Prey Preferences of the Jaguar Panthera Onca Reflect the Post-Pleistocene Demise of Large Prey .” Front Ecol Evol , vol. 3, 2016, doi:10.3389/fevo.2015.00148

Pavlik, Steve. “ Rohonas and Spotted Lions: The Historical and Cultural Occurrence of the Jaguar, Panthera Onca, among the Native Tribes of the American Southwest .” Wicazo Sa Review , vol. 18, 2003, pp. 157-175., doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0006

“ Panthera Onca Jaguar .” University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

de Azevedo, Fernando Cesar Cascelli, and Dennis Lewis Murray. “ Spatial Organization and Food Habits of Jaguars (Panthera Onca) in a Floodplain Forest .” Biological Conservation , vol. 137, 2007, pp. 391-402., doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.02.022

Jaguars . World Wildlife Fund.

Mooring, Michael S., et al. “ Natural Selection of Melanism in Costa Rican Jaguar and Oncilla: A Test of Gloger’s Rule and the Temporal Segregation Hypothesis .” Tropical Conservation Science , vol. 13, 2020, doi:10.1177/1940082920910364

“ Jaguar .” San Diego Zoo.

- What's the Difference Between Jaguars and Leopards?

- 18 Magnificent Types of Hawks and Where to Find Them

- 8 Fast Facts You Didn't Know About Cheetahs

- Surprising Facts About Our Favorite Big Cat Species

- Morocco’s Tiny Sand Cats Reveal Behavior Never Before Seen in Wild Cats

- 10 Incredible Glass Frog Facts

- 20 of the World's Most Venomous Snakes

- 11 Incredible Facts About Bull Sharks

- Why the Snow Leopard Population Is Decreasing

- 12 Fascinating Facts About the Amazon River

- 14 Fascinating Facts About Monkeys

- 11 Interesting Facts About Wolves

- 11 Interesting Coatimundi Facts

- 9 Gorgeous Snake Species Around the World

- 8 Fascinating Facts About Bobcats

- 8 Intriguing Facts About the Green Lynx Spider

- Know Before You Go

- South America

Jaguar Facts | Brazil Wildlife Guide

Jaguars & wildlife of brazil's pantanal.

Send Me Travel Emails

Get the Inside Scoop on the

World of Nature Travel

Our weekly eNewsletters highlights new adventures, exclusive offers, webinars, nature news, travel ideas, photography tips and more. Sign up today!

Look for a special welcome message in your inbox, arriving shortly! Be sure to add [email protected] to your email contacts so you don’t miss out on future emails.

Get Weekly Updates

Our weekly eNewsletter highlights new adventures, exclusive offers, webinars, nature news, travel ideas, photography tips and more.

Request Your 2023 Catalog

Discover the World's Best

Nature Travel Experiences

Together, Natural Habitat Adventures and World Wildlife Fund have teamed up to arrange nearly a hundred nature travel experiences around the planet, while helping to protect the magnificent places we visit and their wild inhabitants.

Get Weekly Updatess

Our weekly eNewsletter highlights new adventures, exclusive offers, webinars, nature news, travel ideas, photography tips and more. Sign up today!

Send Us a Message

Have a question or comment? Use the form to the right to get in touch with us.

We’ll be in touch soon with a response.

Refer a Friend

Earn rewards for referring your friends! We'd like to thank our loyal travelers for spreading the word. Share your friend's address so we can send a catalog, and if your friend takes a trip as a first-time Nat Hab traveler, you'll receive a $250 Nat Hab credit you can use toward a future trip or the purchase of Nat Hab gear. To refer a friend, just complete the form below or call us at 800-543-8917. It's that easy! See rules and fine print here.

We've received your friend's information.

View Our 2023 Digital Catalog

View Our 2024/2025

Digital Catalog

Thanks for requesting access to our digital catalog. Click here to view it now. You’ll also receive it by email momentarily.

Polar Bear Tours

African Safaris

Galapagos Tours

Alaska Adventures

U.S. National Parks Tours

Canada & the North

Europe Adventures

Mexico & Central America Tours

South America Adventures

Asia & Pacific Adventures

Antarctica & Arctic Journeys

Adventure Cruises

Photography Expeditions

Women's Adventures

Family Adventures

New Adventures

Questions? Call 800-543-8917

Have a question or comment? Click any of the buttons below to get in touch with us. Hours Mountain Time

- 8 am to 5 pm, Monday - Friday

- 8 am to 3 pm on Saturday

- Closed on Sunday

10 Roaring Facts About Jaguars

By mark mancini | feb 7, 2017.

A few different jaguars have found fame on YouTube over the last few years: In 2013, a National Geographic video of one of the cats taking down an unsuspecting crocodile went viral. And a year later, 4.5 million viewers watched some spectacular footage of one swimming like a champion. But these cats deserve more than just 15 seconds of fame. Here are 10 incredible facts about jaguars that might help you properly appreciate the next hit video.

1. ONLY ONE OR TWO WILD JAGUARS NOW LIVE IN THE UNITED STATES (AS FAR AS WE KNOW).

Wikimedia Commons

These big cats used to have an enormous geographic range, stretching from Argentina to the southwestern United States. In centuries gone by, jaguars were among the top predators in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and southern California. Overhunting, habitat loss, and armed livestock owners completely wiped out the local population in at least three of those states. In 2011, a male was photographed in the Santa Rita Mountains near Tucson, Arizona. Nicknamed El Jefe (Spanish for “the boss”), this cat quickly became a minor celebrity because at the time, no other wild jaguar specimens were known to reside anywhere in the U.S. Then, in 2016, a trail camera in Fort Huachua, Arizona took some snapshots of what looks like a different male. “We are examining photographic evidence to determine if we’re seeing a new cat here, or if this is an animal that has been seen in Arizona before,” Jim deVos, a member of the state’s Game and Fish department, told the press. While there's not yet an official verdict on whether it's El Jefe or there's a new cat in town, you can compare these photos and draw your own conclusions.

2. JAGUARS HAVE DISPROPORTIONATELY STRONG BITES.

"Pound for pound, jaguars pack a stronger punch” than a lion or tiger, says biologist Adam Hardstone-Rose. Back in 2012, Hardstone-Rose co-authored a study that compared the standard bite forces of nine cat species. The data showed that, in terms of sheer power, jaguars can’t compete with tigers, who exert 25 percent more force when chomping down. But proportionately speaking, the smaller felines wield the most powerful bite of any big cat. “The strength of [its] jaw muscles, relative to weight, are slightly stronger than those of other cats. In addition—also relative to weight—its jaws are slightly shorter, which increases the leverage for biting,” Hardstone-Rose explains.

3. THIS MAKES THEM BRUTALLY EFFECTIVE KILLING MACHINES.

Jaguars aren’t finicky. They’ll eat just about any animal they can overpower. Fish, birds, deer, armadillos, peccaries, porcupines, tapirs, capybaras, anacondas, caimans, and nesting sea turtles are just a few of the jaguar’s dinner options. Armadillos, caimans, and sea turtles are all heavily armored creatures whose hides are tough enough to repel most would-be predators, but jaguars aren't daunted: They know where to bite down. Some big cats, like lions, tend to kill by suffocation, biting the windpipe area of the victim’s neck until it asphyxiates. Jaguars take a different approach . When one of these spotted felines goes in for the kill, it generally delivers a swift, powerful bite to the back of target’s head right where the skull meets the spinal cord. With crushing force, the jaguar’s teeth are driven into the neck vertebrae. If all goes well, the bite will efficiently incapacitate the prey animal.

4. JAGUARS WILL TAKE ON BEARS.

To quote Sir David Attenborough , the jaguar is “a killer of killers,” hunting some pretty dangerous game. Consider El Jefe, who has eaten at least one bear. Last year, wildlife biologist Chris Bugbee was leading Mayke, his jaguar-tracking dog, through the famous cat’s territory when they came upon the stripped remains of a young adult black bear. The back of the animal’s skull had been crushed, and some suspicious toothmarks were present. Bugbee also found jaguar scat at the scene. An analysis of the fecal matter revealed strands of black bear hair . According to biologist Alertis Neils—who is also Bugbee’s wife—this is probably the first recorded instance of a jaguar killing a black bear. The ranges of these two species don’t overlap to a great extent, as the former is seldom seen in the U.S. while the latter is considered endangered in Mexico [ PDF ]. Regarding El Jefe’s bear hunt, Neils said , “It was north against south, and south won.”

5. THEY’RE ALSO GREAT SWIMMERS.

All felines can swim, but many would prefer to stay high and dry. Jaguars, in contrast, voluntarily enter rivers and streams so often that they’re considered the most aquatic of the big cats. The cats have been known to pursue fish and caimans underwater. On hot days , they can even be found wallowing in bodies of water to cool off. Well-suited for endurance swims , the felines have been seen traversing rivers that are a mile wide or more. Don’t believe us? Watch this .

6. “BLACK PANTHERS” ARE ACTUALLY LEOPARDS AND JAGUARS.

Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 4.0

Most people assume that the black panther is a distinct species of feline. But the “black panther” is really an umbrella term that applies to individual leopards or jaguars who have a condition known as melanism. Melanistic animals are born with an unusually large amount of dark-colored pigment in their skin, scales, feathers, or fur. This can give them a striking, jet black look from head to toe. Jaguars and leopards with melanism—so-called black panthers—are so dark that, in many cases, you can barely see their spots. At the other end of the spectrum are albino jaguars, which are a good deal rarer than melanistic ones. Nonetheless, a few have been sighted in Paraguay .

7. PREHISTORIC JAGUARS WERE BIGGER THAN MODERN ONES.

The fossil record tells us that jaguars first evolved in Eurasia, where the species—whose scientific name is Panthera onca —has long since gone extinct. The cats then crossed the Bering land bridge and entered the Americas around 1.5 million years ago. The average jaguar was a lot larger in those days, with a wide range. Fossilized jaguar bones have been found in Florida, Maryland, Nebraska, Tennessee, and Washington. From this fossil record, scientists have deduced that prehistoric P. onca were 15 to 20 percent bigger than the animals alive today.

The decrease in body size might have helped jaguars survive the last ice age. For predators back then, the competition was fierce. While prehistoric jaguars were impressively large, they still would’ve been dwarfed by the saber-toothed cat Smilodon fatalis and by another massive feline called the American lion. Both were big-game hunters. So to avoid directly competing with either species, jaguars probably started pursuing smaller animals like peccaries. Some paleontologists suspect that, over time, this trend would’ve forced the jags themselves to get smaller . In the end, the shrinkage paid off: Most of the mega-mammals on which Smilodon and the American lion depended gradually died out. But the jaguars’ relatively diminutive prey animals are still around today. Size matters in nature—but bigger isn’t always better.

8. GUYANA’S COAT OF ARMS INCLUDES TWO JAGUARS.

The South American republic adopted its current coat of arms (pictured above) on February 25, 1966 . Since the jaguar is Guyana’s national animal , it’s fitting that two of them appear in the design. As you can see, the cats come with props. The one on the left is grasping a pick axe, which represents the country’s mining industry . Meanwhile, on the right, we see a cat that’s grasping a sugar cane and a stalk of rice. These symbolize the historic importance of both crops—plus those who farm them—in Guyana.

9. THE JAGUAR IS THE ONLY NATIVE NORTH AMERICAN FELINE THAT ROARS.

This species belongs to the same genus, Panthera, that includes the lion, tiger, leopard, and snow leopard. With the exception of the snow leopard , all of those cats emit deep roars—and so, too, does the jaguar. The same cannot be said of the other felines that roam North America. Mountain lions, bobcats, lynx, ocelots, jaguarundis, and margays emit all kinds of sounds (ranging from low hisses to horrific shrieks ), but none are considered genuine roars. On the flip side, those Panthera cats cannot purr , which is something that many of their smaller relatives—including the tabby who lives in your house—do with gusto. Life is full of tradeoffs.

10. A NEWBORN CUB WAS NAMED AFTER THE OWNER OF THE NFL'S JACKSONVILLE JAGUARS.

No wild jaguar has set foot in Florida since prehistoric times. But the Jacksonville Zoo and Garden does have an award-winning jaguar display, and it was the first American zoo to ever breed these near-threatened felines on a regular basis. On July 18, 2013, the 50th cub was born at the zoo—the same birthday as the owner of the Jacksonville Jaguars, Shahid Khan. So, when a contest was held to determine what the kitten's name would be, the public chose Khan . In July 2016, Jaguars wide receiver Arrelious Benn and safety Jarrod Wilson dropped by the zoo to help the cat celebrate his third birthday.

Premium Content

Path of the Jaguar

If forward-looking conservationists prevail, this wanderer will live on.

( Update: Big cats can protect humans from the rise of future pandemics. See more in National Geographic News. )

At dusk one evening, deep in a Costa Rican forest, a young male jaguar rises from his sleep, stretches, and silently but determinedly leaves forever the place where he was born.

There's shelter here, and plenty of brocket deer, peccaries, and agoutis for food. He has sensed, too, the presence of females with which he might mate. But there's also a mature male jaguar that claims the forest—and the females. The older cat will tolerate no rivals. The breeze-blown scent of the young male's mother, so comforting to him when he was a cub, no longer binds him to his home. So he goes.

But the wanderer has chosen the wrong direction. In just a few miles he reaches the edge of the forest; beyond lies a coffee plantation. Pushed by instinct and necessity, he keeps moving, staying in the trees along fences and streams. Soon, though, shelter consists only of scattered patches of shrubs and a few trees, where he can find nothing to eat. He's now in a land of cattle ranches, and one night his hunger and the smell of a newborn calf overcome his reluctance to cross open areas. Creeping close before a final rush, he instantly kills the calf with one snap of his powerful jaws.

The next day the rancher finds the remains and the telltale tracks of a jaguar. He calls some of his neighbors and gathers a pack of dogs. The hunters find the young male, but they're armed only with shotguns; anxious, they shoot from too great a distance. The jaguar's massively thick skull protects him from death, but the pellets blind him in one eye and shatter his left foreleg.

Crippled now, unable to find his normal prey in the scrubby forest, let alone stalk and kill it, he's driven by hunger to easier meals. He kills another calf on an adjacent ranch, and then a dog on the outskirts of a nearby town. This time, though, he lingers too long. Attracted by the dog's howls, a group of villagers tree him and, though it takes many blasts, kill him. Jaguars, they say, are nothing but cattle killers, dog killers. They are vermin. They should be shot on sight, anytime, anywhere.

This sad story has been played out thousands of times throughout the jaguar's homeland, stretching from Mexico (and formerly the United States) to Argentina. In recent decades it's happened with even greater frequency, as ranching, farming, and development have eaten up half the big cat's prime habitat, and as humans have decimated its natural prey in many areas of remaining forest.

Alan Rabinowitz envisions a different ending to the story. He imagines that the young jaguar, when he leaves his birthplace, will pass unseen by humans through a near-continuous corridor of sheltering vegetation. Within a couple of days he'll find a small tract of forest harboring enough prey for him to stop and rest a day or two before resuming his trek. Eventually he'll reach a national park or wildlife preserve where he'll find a home, room to roam, plenty of prey, females looking for a mate.

You May Also Like

To save jaguars, he acts like a jaguar

An ‘impenetrable’ wildlife sanctuary in Argentina opens to the world

A surprising must-wear for European monarchs? Weasels.

Rabinowitz is the world's leading jaguar expert, and he has begun to realize his dream of creating a vast network of interconnected corridors and refuges extending from the U.S.-Mexico border into South America. It is known as Paseo del Jaguar—Path of the Jaguar. Rabinowitz considers such a network the best hope for keeping this great New World cat from joining lions and tigers on the endangered species list.

Rabinowitz began his work with the Wildlife Conservation Society and now heads the Panthera Foundation, a conservation group dedicated to protecting the world's 36 species of wild cats. The foundation's current work represents a radical change in Rabinowitz's conservation philosophy from just a decade ago. In the 1990s, having censused jaguars across their range, Rabinowitz and other specialists identified dozens of what they called jaguar conservation units (JCUs): large areas with perhaps 50 jaguars, where the local population was either stable or increasing. At the heart of most of the JCUs were existing parks or other protected areas, which Rabinowitz hoped to expand and secure with surrounding buffer zones. "I felt that the best thing we could hope to do was to lock up these great populations in these fragmented areas," he said.

Within a few years, though, the new science of DNA fingerprinting—studying genetic material to determine family and species relationships—revealed an amazing fact: The jaguar is the only large, wide-ranging carnivore in the world with no subspecies. Simply put, this means that for millennia jaguars have been mingling their genes throughout their entire range, so that individuals in northern Mexico are identical to those in southern Brazil. For that to be true, some of the cats must wander regularly and widely between populations.

Rabinowitz and his colleagues went back to their data to see whether the preserves could still be linked with habitat adequate to support a traveling jaguar. "Lo and behold," Rabinowitz said, "while good jaguar habitat, where the cats can live and breed, has decreased by 50 percent since the 1900s, habitat a jaguar can use to travel through has decreased only by 16 percent. Most of it is intact and contiguous. These places are like little oases—very small patches that jaguars will come to, use a while, and then leave. We were writing these places off because they're not habitat where a permanent jaguar population can live. Now they're turning out to be crucial."

Rabinowitz hopes to convince national governments throughout the jaguar's range to maintain this web of habitat through enlightened land-use planning, such as choosing noncritical areas for major developments and road construction. "We're not going to ask them to throw people off their land or to make new national parks," he said. The habitat matrix could encompass woodlands used for a variety of human activities from timber harvest to citrus plantations. Studies have shown that areas smaller than one and a half square miles can serve as temporary, one- or two-day homes—stepping-stones—for wandering jaguars.

While the habitat making up the proposed network is mostly intact for now, prompt conservation action will be needed to protect it, especially in certain areas of Central America and Colombia, where some jaguar travel paths already are critically tenuous. By studying satellite photographs and airplane surveys, and walking sections of the proposed corridor to follow up on reports from local people, Rabinowitz and his team can identify the segments most in need of protection. He then can go to government decision-makers with hard scientific data, he said. "Our first challenge is looking at corridors where there's just a single tendril. We've got to lock up these areas."

Diana Hadley of the Arizona-based Northern Jaguar Project works to protect the northernmost jaguar population in Mexico, with the long-term goal of seeing the species return to the United States. Hadley said the project and its Mexican partners "fully support" Paseo del Jaguar. "If these magnificent animals are ever to reoccupy appropriate habitat north of the border," she said, "the stepping-stones in the jaguar corridor are essential." Paseo del Jaguar ranks with the world's most ambitious conservation programs, and realizing it will take many years. Rabinowitz is focusing first on Mexico and Central America, where officials in all eight countries have approved the project. Costa Rica has already incorporated protection of the corridor into laws regulating development.

Later he'll tackle South America, where landscapes and political situations are more diverse and challenging. Rabinowitz is encouraged, though, by his audiences' emotional response when he talks about jaguars—a response based on the animal's enduring aura of beauty, strength, and mystery. Indigenous peoples around Mexico's central plateau, and the Maya, farther south, incorporated the jaguar into their art and mythology. Today even mobile-phone-carrying government ministers sitting in urban offices feel what Rabinowitz calls "a powerful cultural thread binding them to their ancestors. Nobody can say that the jaguar is not part of their own heritage," he said. "What better unifying symbol can there be than the jaguar?"

Related Topics

- WILDLIFE CONSERVATION

On the Trail of Jaguar Poachers

This floppy-nosed antelope was nearly gone. 20 years later, it’s thriving.

How these parrots went from the tropical jungle to the concrete jungle

A few jaguars now roam the Arizona borderlands—why that’s a big deal

There are two northern white rhinos left on Earth. Can a controversial approach save them?

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

- History & Culture

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- Photography

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Conservation

Wildlife Management

Will jaguars be reintroduced in the us.

Large predator conservation is going well in the Lower 48. Wolf packs are thriving in Yellowstone and grizzly bear numbers have expanded considerably since they were listed as endangered in 1975. For some folks this is great news; for others, not so much. But one group of scientists believes there’s another large predator that needs rehabilitation: jaguars.

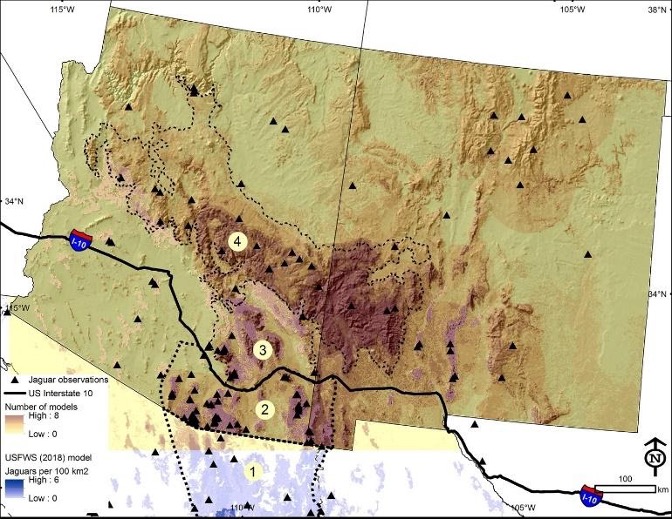

Led by Eric Sanderson of the Wildlife Conservation Society, a group of 16 scientists released a paper in May calling for jaguars to be reintroduced in a 31,800-square-mile tract of land in central Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. The article, published in Conservation Science and Practice , made headlines around the world as public fascination gathered around yet another of North America’s sharp-toothed mammals.

Coverage of the proposal was largely positive, but the idea wasn’t a slam dunk. Ranchers in New Mexico were none too thrilled , and hunters are concerned about jaguars reducing the number of game animals.

This topic is too large to cover sufficiently in one article, but we’ll do our best to give you the outlines. First, let’s look at what the proposal says.

The Proposal Sanderson and his team want jaguars in Arizona and New Mexico because they believe this area constitutes a small portion of the species’ native range. Sanderson believes jaguar reintroduction is a “justice issue,” and the move would help solidify the species’ presence globally.

“If a country extirpates a species, that country is on the hook to bring that species back,” Sanderson said in an interview with MeatEater. “It’s not right or moral for a country to extirpate its wildlife.”

The U.S. currently doesn’t have a breeding population of jaguars. However, they are occasionally seen in southern states, and scientists believe the closest stable population resides in northern Mexico. Sanderson and his team argue that this group is unlikely to populate New Mexico and Arizona naturally due to the loss of habitat to development, border wall infrastructure, and Interstate 10.

“It would be awesome if they could get there on their own,” Sanderson said. “It was with great regret and reluctance that the group of authors turned our minds to reintroduction. [Natural dispersal] is just very unlikely.”

Sanderson and his team chose an area in New Mexico and Arizona that they believe constitutes ideal jaguar habitat. The paper argues that the area contains sufficient water and shelter, along with the kinds of animals jaguars prefer to eat (coues deer being first on the menu).

Reintroduction efforts would likely begin by working with either captive-bred jaguars or translocating individuals from existing wild populations. The paper cites one reintroduction effort currently underway in Argentina that constructed a captive-breeding center to train young jaguars to hunt prey in the relocation area.

John Polisar, another of the paper’s co-authors, called this a “soft release,” and reported to MeatEater that six jaguars have been released in Argentina since January. These jaguars, two mothers with two cubs each, are all still alive, eating well, and not dispersing outside the reserve.

Ultimately, Sanderson says, that area could be home to 60 to 100 jaguars.

You can read the full paper here .

Conflict 1: Why Jaguars? When we asked Sanderson and Polisar why they believe jaguars deserve to be reintroduced, they both cited the species’ historic presence in the area.

“Jaguars are part of the native fauna. Not exotics. Why do we even have a question like this?” Polisar asked. “They are as much a part of the endangered species as mussels, fish, salamanders, lizards.”

Sanderson also pointed out that the area is ecologically unique in the jaguar’s native range. “Species population isn’t about just preserving one population somewhere,” he said. “If you follow that logic to its end, it suggests that we should conserve or restore the jaguar population in all the ecological settings where they occur. And this particular ecological setting is unique in all jaguar range.”

Unfortunately, conservation is often a zero-sum game. The money that could go to relocating and managing jaguars in New Mexico and Arizona would necessarily not be used to conserve other species that are endangered or threatened in the U.S.

“The basic question for everyone is, with so many species currently listed under the [Endangered Species Act] needing our help, and 173,000 jaguars living from Sonora [Mexico] to Argentina, how important is it that we pour millions of dollars into recovering the Jaguar in AZ and NM?” asked Jim Heffelfinger, wildlife science coordinator for the Arizona Game and Fish Department. “I know they are cool, they really are, but we have obligations to so many species.”

When pressed with this particular question, Polisar admitted that complete funding will be difficult to muster, especially from the federal government. But he pointed out that other countries in Central and South America have managed to fund jaguar conservation efforts despite far less prosperous economies.

“I can’t say I know exactly where the funding will come from, but there are a number of people who find this topic inspirational,” he said. “Over 240 media outlets picked up this paper. People find these stories intriguing, this spark of wild that you could put back in.”

Conflict 2: Native Range? The primary justification for jaguar reintroduction rests on the idea that the cats used to live in the proposed recovery area but were extirpated by humans. This sounds easy enough to determine, and the map on the website of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Department shows jaguars extending into New Mexico, Arizona, California, Texas, and Louisiana.

Digging into the weeds, this question starts to look a lot more complicated.

Sanderson and his team report 16 independent jaguar observations between 1890 and 1964 within the recovery area, and 16 observations in areas north, south, and east of the area in Arizona and New Mexico. A female cat with cubs was trapped in 1910 (no extant physical evidence), and another female was shot in 1963 (photographs exist).

The persistence of these observations, Sanderson told us, indicates that jaguars occupied the territory continually and had established a breeding population in the area.

However, most of the evidence for jaguars within the recovery zone comes from personal testimony and has no existing physical evidence (photographs or skin/skull). One of the 16 jaguar instances, for example, is described as a “general observation” made in 1905 and recorded in an 1931 text called “ Mammals of New Mexico .”

“As someone who has fielded ‘jaguar’ calls periodically for 30 years, I would say including those without physical evidence is problematic,” Heffelfinger pointed out.

The evidence of female jaguars with cubs suggests that the cats were breeding within the recovery zone. The question, of course, is whether this evidence proves the species was “native” to the area. If, for example, jaguars established a presence between 1800 and 1900, does that make them native?

Heffelfinger says no. “This wasn’t their historic range. They came up here and dispersed, and there was some reproduction before humans got here, but to me, they’re not a native species.” He also noted that unlike the Native American Tribes south of the border, jaguars don’t figure into the motifs and stories of the tribes in the Southwest. “Sometimes there’s a mention of a tiger, but it’s not part of the Southwest,” he said.

Sanderson points out in the paper that jaguars are “notoriously cryptic,” and the recovery zone was sparsely populated by humans until the second half of the 20 th century. These factors suggest that even one jaguar sighting indicates the presence of a more significant population.

This still might not be enough to convince those opposed to jaguar reintroduction. Sanderson’s paper only includes evidence of jaguars within the recovery zone back to 1890, so if a species must exist for a more extended period to be considered “native,” the jaguar might not make the cut.

Check out Sanderson’s database of jaguar sightings to look at the data for yourself.

Conflict 3: Hunters and Landowners?

Moving jaguars into New Mexico and Arizona will require serious buy-in from the local residents (not to mention state wildlife agencies), and Sanderson’s team welcomes that dialogue.

“We’re not proposing that anyone should do it right away,” Sanderson told us. “We’re proposing that the next step is to have a long period of consultation with the people who live in that area, the government agencies and local communities, and the various interests, including hunting and livestock. Only if that’s a successful consultation would we want to move to the practical considerations.”

Ranchers will be a big part of that conversation, and they’re understandably opposed.

“They want these wolves, they want these jaguars—then they need to get their checkbooks out,” Randell Major, president of the New Mexico Cattle Growers Association, told the Santa Fe New Mexican . “This is a taking of private property. People are trying to make a living out here.”

Both Sanderson and Polisar acknowledged that hunters are also among the groups that need to be consulted. When asked whether hunters should worry about jaguars affecting deer and elk numbers, both scientists admitted the possibility, but neither believed that jaguars would affect cervids in the same way that wolves have. The cat’s reproductive capacity is lower and populations occur at much lower densities.

“It seems a valid concern, yet one that does not worry me too much,” Polisar said.

It’s unclear whether these assurances will be enough to convince hunters in Arizona and New Mexico. The paper’s authors admit that they do not have any survey data on how the general public perceives jaguar reintroduction, but it isn’t difficult to find hunters who object to the plan.

“Just what the Gila Elk Herd needs, more predators,” said Josh Darnell in response to a story published by a local news outlet in New Mexico. “The reintroduction of predators in recent history to the Gila has and is taking one of the most fascinating elk herds and decimating it.”

Hunting groups in Arizona have also voiced opposition.

“We’re diametrically opposed to the reintroduction of jaguars,” Don McDowell, Sr., president of the Arizona Deer Association, told MeatEater. “The jaguars we have here are rogue. None of their historic range is in Arizona.”

Heffelfinger told us that scientists don’t have enough information to say what the impact of jaguars will be on cervids in the area. He’s unsure that jaguars will thrive in the recovery area, but even if they did, the cats do not exist in that type of ecosystem anywhere else in the world.

“My gut feeling is that they wouldn’t have the impact of wolves. I don’t have a fear that they’ll devastate wildlife, but my short answer is, I don’t know,” he said.

Last Word Right now, it doesn’t look like jaguars will be reintroduced into the U.S. any time soon.

The jaguar recovery plan published by the USFWS in 2018 called for uninterrupted habitat connectivity, the preservation of habitat in southern Arizona and New Mexico, and jaguar-friendly ranching practices. But the agency did not recommend reintroduction and it did not list Sanderson’s recovery area as potential habitat.

Still, as with wolves and grizzlies, public pressure can bring a species back from the verge of extinction. Only time will tell if there’s enough of that pressure to introduce (or reintroduce) the world’s third-largest cat on American soil.

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Is Washington About to Get Grizzly Bears?

After decades of absence, grizzly bears may be returning to Washington’s North Cascades. The US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is considering a reintroduction plan that aims to put the species back on a large swath of their historical home range. Under the plan, the agency is proposing to reintroduce seven to ten bears over a period of five to ten years, with the goal of establishing a self-sustaining population of 25 animals. Long-term, the...

Should Wolves be Reintroduced to Colorado?

My home state of Colorado is ground zero for the latest battle over wolves. A proposal to reintroduce wolves here has garnered enough signatures to make the ballot this fall. Voters will be asked to approve a measure to bring wolves back to the state. Now there’s a wildlife management storm brewing that has divided the state into passionate but predictable factions. But first, a little history lesson. Will History Repeat Itself? Two decades have...

Should We Bring Seal Hunting Back to the Northeast?

The industrial sealing era of the 1800s decimated our native seal populations, pushing them close to extinction in the US, and putting millennia of indigenous seal-hunting culture in jeopardy. Now, as tens of thousands of grey and harbor seals return to New England waters, it’s drawing the attention of fishermen and biologists alike, often for the wrong reasons. Given their rapid comeback, is there now a reason to resume the hunt, despite all the...

Smithsonian Voices

From the Smithsonian Museums

SMITHSONIAN TROPICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE

Can Humans and Jaguars Coexist? A Wildlife Biologist Uses Technology and Education to Reduce Conflict

From tracking large felines across the continent to helping rural communities protect biodiversity, Panamanian biologist Ricardo Moreno turned his childhood dream into a mission

Vanessa Crooks

:focal(1280x768:1281x769)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9d/bb/9dbb1fae-7825-4f2d-a29c-7351d1c15522/ricardo_moreno_thumb.jpg)

The jaguar ( Panthera onca ) is the biggest feline native to the America continent, and the third largest in the world after the tiger and the lion. They are considered key predators because they maintain a balance in the ecosystem by regulating the population of other species. Jaguars can be found anywhere from southern parts of the U.S. to Argentina. Panama, the bridge between Central and South America, is part of the Mesoamerican biological corridor, or the “jaguar corridor”, and thus an important part of their habitat.

But jaguar populations in the continent are diminishing, and it is now a critically endangered species. The greatest threats to their survival are loss and fragmentation of their habitat, diminishing preys, being struck by vehicles, poaching, illegal captivity, illegal trafficking of pelt and other parts, and misinformation. In Panama, jaguars are also often killed by cattle ranchers, a short-term solution to deter jaguars from preying on their cows.

Wildlife biologist and research associate at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) Ricardo Moreno has dedicated more than 20 years of his career to biodiversity conservation and to the jaguar’s protection. A graduate from University of Panama in 2002 with a degree in Biology, and a Masters in Conservation and Wildlife Management from the Universidad Nacional of Costa Rica, Moreno started researching Panamanian felines, including the jaguar, as early as 1996, and learning about the situation this species faces in the region.

That is why in 2006 he started the Yaguará Panama Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of jaguars and the forests where they live. To reduce the human-jaguar conflict, the foundation focuses on educating and working with people and communities that coexist with jaguars, developing environmentally sustainable alternatives and economic activities that will help preserve the species and habitats.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4b/ee/4beeeb8f-1044-4e97-b25b-1bafee75bcda/hembra_jaguar_con_rastreador_gps.jpg)

“Jaguars are a very important part of the ecosystem. They need to be out there, so that they can fulfill their role in nature,” Moreno points out. “Respect the jaguar’s territory and hunting instinct.”

By using scientific information and technology, such as tracking and monitoring the movements and behaviors of jaguars and other large felines by using GPS collars and camera traps, Moreno and fellow researchers can know where there are potential interactions with humans and therefore where conflicts might arise. As recently as 2019, Moreno and Yaguará finally managed to capture and put a GPS collar on a jaguar in the Darién Province, which Moreno referred to as “a historical moment for science in Panama”.

In farming communities where there are jaguar-cattle conflicts, Yaguará works with cattle ranchers to implement tried-and-true systems such as installing solar-powered electrical fencing for the cattle enclosures, putting water tanks in the pastures so cows don’t wander into the forest (the jaguar’s territory) to drink from rivers and streams, and putting collars with bells and lights on cows to startle and keep jaguars away.

The foundation also collaborates with rural and indigenous communities, such as Quebrada Ancha in the Chagres National Park, to teach them about the jaguar’s role in the ecosystem and how to benefit from their conservation, with activities such as casting jaguars’ pawprints and selling them as souvenirs and managing ecotourism in their area to help prevent destruction of the biodiversity.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e3/86/e386c25f-6fb2-4e03-ac0b-150a853d558d/fot_elliot_brown_yaguara.jpg)

Moreno and Yaguará also spread knowledge and awareness by training environmental developers and creating projects to engage communities in biodiversity protection, offering seminars, webinars, and workshops, publishing scientific papers, and through media campaigns and interviews. Moreno himself has written and co-authored over 120 articles of scientific disclosure, participated in international conferences, and appeared in documentaries for National Geographic, the Smithsonian Channel and more.

His passion and dedication have not gone unnoticed: he was named Emerging Explorer by National Geographic in 2017 and is a Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations. On behalf of Yaguará Panamá Foundation, he received the Environmental Excellence Award from Panama’s Ministry of Environment (MiAmbiente).

He still feels disheartened when he hears news of another jaguar killed, but he continues working and encouraging others to do the same.

“Anything helps, and anyone can do it, planting trees, caring for the environment. We as human beings have the ability to destroy, but we can also build,” he says. “I know change is possible and it’s happening.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/dc/97/dc975a16-0669-4ac7-8208-414b1c0d1147/ricardo_moreno_1.jpg)

Vanessa Crooks | READ MORE

Vanessa Crooks is a bilingual journalist and writer located in Panama City, Panama, working to bring science to all audiences. She is also an illustrator, graphic designer and animator.

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Sweepstakes

Brazil Is Home to One of the Highest Concentrations of Jaguars on the Planet — Here's How to See One From Your Hotel

Make Refúgio Ecológico Caiman your home base, and you’re pretty much guaranteed to lock eyes with one of the majestic cats.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Karen-Catchpole-high-res-Karen-Catchpole-2000-96bc4a9557d44827be95624f221ea866.jpeg)

A jaguar stepped onto the dirt road in front of us and approached our group slowly, the pads of her enormous feet moving inaudibly. Then, in one graceful swoosh, she flicked the tip of her tail and glanced over her shoulder before slinking into the underbrush.

It wasn’t even 8 a.m. and I’d already seen a wild jaguar. And you can too.

The mostly flat, seasonally-flooded Pantanalgrasslands cover more than 81,000 square miles in Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay. According to Dr. Rafael Hoogesteijn, the Conflict Program Director for Panthera's Jaguar Program, there are nine jaguars per 40 square miles in Brazil’s Pantanal — one of the highest densities on the planet. Wildlife never comes with a guarantee, of course, but if you’re going to see a jaguar in the wild your chances are higher here than almost anywhere else on earth.

To further increase your chances of a sighting, visit during dry season (August–December), when the animals congregate around the few remaining water sources and less foliage makes for better visibility. Bed down at Refugio Ecologico Caiman , and you’ll have even better chances of locking eyes with one of these majestic cats. There are many hotels and lodges in the Pantanal, but only Caiman is located on its own nearly 14,000-acre private protected reserve and is home to its own jaguar conservation program.

Like most areas of the Pantanal, the land that Caiman was built on what used to be a cattle ranch (called a fazenda), where jaguars were viewed as pests because they preyed on the herd. Despite laws prohibiting the killing of jaguars, cattle ranchers in the Pantanal still hunt them. In 2004, the owners of Caiman decided to take action, dedicating about ten percent of their 130,000-acre property to conservation. The herds were removed, and the land naturally shifted back to habitat for jaguars. The population of big cats has since flourished: animals can be spotted year-round.

Jaguars are so common in the Caiman preserve that, for safety and mobility, most excursions are done in African-safari style vehicles. All excursions are led by a local guide (often a former cowboy) and a trained biologist.

When not out spotting jaguars, guests can relax in one of three luxurious lodges that comprise the Caiman property. Each small-capacity lodge has its own staff, kitchen, and pool. Large well-furnished living rooms and communal meals lend the feeling of staying in a chic house, while encouraging guests to recap the day’s adventures with other travelers.

One activity you won’t be able to do during your stay: go outside for a jog, unless you want to be chased down by a jaguar — an apex predator, might we add.

Despite the property’s many attractions, jaguars remain the big draw. During my time at the camp, I saw the same jaguar from before three more times from the safari truck, enjoyed a very rare (and heart pounding) sighting of a large male while hiking, and saw another unidentified individual during a night drive. And let me tell you: it never, ever got old.

Jaguar Recovery: Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is this proposal to reintroduce jaguars to the United States? 2. What about the proposal for protected habitat? 3. Why is this petition so important? 4. Are jaguars native to the United States? 5. Why did jaguars decline so drastically in the United States? 6. Can’t we just rely on jaguars wandering north from Mexico? 7. Why does this reintroduction petition target New Mexico’s Gila National Forest? 8. Long term, how many jaguars could this area support? 9. Will reintroduced jaguars be legally protected? 10. Won’t people kill off the jaguars? 11. Do you expect jaguars will wander out of the Gila National Forest and into other areas? 12. Once re-established, what role will these jaguars play in the ecosystem? 13. Will jaguars pose a threat to people? 14. Why are you asking for additional habitat to also be protected? 15. Does your request for additional critical habitat include Tribal lands? 16. How does this petition fit into the fight to combat the global wildlife extinction crisis? 17. Will the actual reintroductions be dangerous to jaguars? 18. Where will the reintroduced jaguars come from? 19. What’s the process for this petition? 20. With limited resources for wildlife reintroduction, and with other species at greater risk of extinction, why prioritize reintroducing jaguars to North America? 21. How do you know this is going to work? 22. How can I help?

1. What is this proposal to reintroduce jaguars to the United States?

In December 2022 the Center for Biological Diversity petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to reintroduce endangered jaguars to the Gila National Forest in New Mexico. Ultimately this could lead to a population of more than 100 jaguars living in the southwestern United States, primarily in an area known as the Mogollon Plateau, a region of mainly public lands between Arizona’s Grand Canyon and the Gila National Forest.

2. What about the proposal for protected habitat?

Our December 2022 petition also asks the federal government to protect about 14.6 million acres in Arizona and New Mexico as "critical habitat” for jaguars. Most of it, about 84%, consists of federal lands. After designation, the federal government would not be allowed to destroy such critical habitat (even if special interests demand).

3. Why is this petition so important?

Jaguars once lived throughout much of the United States but were killed off. They were placed on the endangered list in 1972. While there have been occasional sightings of jaguars in the United States since then, today there’s only one known jaguar living north of Mexico. And, over the past several decades, only males have wandered north. If jaguars are ever going to have a viable U.S. population, we need to protect more of their most important habitat and actively reintroduce them into ideal habitat that scientists have identified.

4. Are jaguars native to the United States?

The jaguar, the third-largest cat species in the world, evolved in North America hundreds of thousands or even millions of years before it expanded its range southward to Central and South America. Paleontologists have identified ancient jaguar remains from states as far afield as Nebraska, Tennessee and Florida. Native Americans depicted large spotted cats in artwork and described them in oral histories hundreds of years before Europeans arrived in North America. As late as the 1700s, jaguars could still be found from the Carolinas to California — including the Southwest.

5. Why did jaguars decline so drastically in the United States?

After Europeans arrived in North America, jaguars were killed for their beautiful spotted pelts and to protect livestock. As forests were cleared and wetlands were drained, jaguars had fewer places to hide. They survived in the Southwest the longest, sheltered in semi-arid, rugged terrain that resisted widespread settlement. But beginning in 1915, Congress appropriated annual funds for the U.S. government to systematically kill carnivores on behalf of the livestock industry. The Fish and Wildlife Service trapped and killed the last resident U.S. jaguar in Arizona in 1964 — two years before changing sentiments led to passage of the first endangered species protection law and eight years before the jaguar was placed on the list of endangered species.

6. Can’t we just rely on jaguars wandering north from Mexico?

It is not known how many jaguars live in northern Mexico, but the two populations, one south of Arizona and one south of Texas, may be in decline. In recent decades a few have wandered over the border and into the United States. Typically these intrepid travelers are males, so it’s not reasonable to expect that a viable population can get established relying on those wanderers. Additionally, the United States has been erecting and expanding physical impediments along the U.S.-Mexico border that make it much more difficult for jaguars and other wildlife to move in through travel corridors. Reintroducing jaguars to the United States will help jump-start a viable population if it can connect to those in Mexico and improve genetic diversity.

7. Why does this reintroduction petition target New Mexico’s Gila National Forest?

Rugged and remote, the 3.3-million-acre Gila National Forest in western New Mexico is one of the largest national forests in the continental United States. It has a low road density, sizable areas where livestock grazing is not permitted, and plenty of deer and elk to serve as a prey base for a jaguar population. Scientists say that it’s one of the best spots to help bring back jaguars. We are also asking the Fish and Wildlife Service to investigate other potential areas for reintroductions in Arizona and New Mexico.

8. Long term, how many jaguars could this area support?

With tolerance and proper protections, we think the southwestern United States could ultimately support a jaguar population of at least 100.

9. Will reintroduced jaguars be legally protected?

Yes. Jaguars are protected under the Endangered Species Act. If it grants our petition, the Fish and Wildlife Service would develop a management rule to guide reintroduction. The Center for Biological Diversity would advocate for robust legal protections as part of that rule. Ultimately the management rule would have to ensure the recovery of the jaguar, a right that the jaguars would continue to maintain and that conservationists could enforce in court.

10. Won’t people kill off the jaguars?

Sadly, poachers kill all types of creatures, even including endangered animals. But jaguars are cryptic, only occasionally vocal, excel in rugged terrain, and are wary of people. With better funding for protecting wildlife in the United States than in other nations supporting jaguars — and with most people inclined to act lawfully — illegal killings should be rare. The Center will advocate for dogged legal prosecution and punishment for anyone illegally killing a jaguar.

11. Do you expect jaguars will wander out of the Gila National Forest and into other areas?

Yes. Jaguars are highly mobile and, most typically, young males tend to set out on their own in search of new territories. Over time, jaguars reintroduced to the Gila National Forest or their offspring will seek new places to live, especially on the Mogollon Plateau and on the sky islands where they can enjoy functional connectivity to jaguars in Mexico.

12. Once re-established, what role will these jaguars play in the ecosystem?

Like other large carnivores, jaguars are a keystone species playing crucial roles in shaping the evolution of prey populations like deer and elk, as well as controlling harmful disease outbreaks. In the three decades since wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park, scientists have discovered surprising benefits to other animals and even plants. Jaguars were present for hundreds of thousands if not millions of years in what is now the United States. Returning them to a small portion of their historic range will allow them to again play their natural role and possibly open our eyes to how restored southwestern ecosystems keep themselves in balance.

13. Will jaguars pose a threat to people?

People have coexisted with large carnivores for thousands of years around the world, including jaguars in North America. Jaguars have no desire to interact with people; attacks on humans are exceedingly rare and typically precipitated by jaguars being provoked or harassed by hunters and their dogs. We can coexist with jaguars in the Southwest again with a combination of education, respect and tolerance.

14. Why are you asking for additional habitat to also be protected?

Right now, a little over 700,000 acres in Arizona are protected as “critical habitat” for jaguars. That’s simply not enough if jaguars are going to recover and thrive in the United States. Jaguars tend to be solitary, and each has a relatively large home range. Based on modeling criteria, previous studies and plans, and historic information about the presence of jaguars, we’ve asked that more than 14 million acres be protected for jaguars in Arizona and New Mexico. These geographic areas, including sky islands, will help ensure jaguars can survive in the Southwest and also travel between areas in the U.S. and northern Mexico.

The requested area includes much of the Mogollon Plateau in the two states. In Arizona it also includes portions of the Rincon, Santa Catalina, Galiuro, Winchester, Pinaleno and Santa Teresa mountains, and farther southeast, portions of the Chiricahua, Dos Cabezas, Swisshelm (and in New Mexico) Peloncillo, Animas, San Luis, Big Hatchet and Little Hatchet mountains.

15. Does your request for additional critical habitat include Tribal lands?

It does not. Instead we’ve asked the Fish and Wildlife Service to consult with the White Mountain Apache Tribe and the San Carlos Apache Tribe about what habitat protections might be appropriate on Tribal lands.

16. How does this petition fit into the fight to combat the global wildlife extinction crisis?

One species goes extinct every hour or so, and we’re on track to lose 1 million species in the coming decades. If we’re going to halt the extinction crisis, we have to act boldly and with vision. It isn’t always enough to simply stop forests from being clear cut or wetlands from being drained. We need to act proactively to preserve life on Earth. Reintroducing jaguars to the United States is a prime example of the ambitious, courageous steps we must take to save species before it’s too late.

17. Will the actual reintroductions be dangerous to jaguars?

Anytime you capture and handle wildlife there is potential risk, so we urge utmost care to ensure that no jaguar would be injured. The Fish and Wildlife Service would consult with jaguar experts to develop protocols to protect these cats during the process. Those protocols would be made public as part of the environmental review process.

18. Where will the reintroduced jaguars come from?

It will be vital not to imperil any existing population of jaguars while reintroducing them to the United States. Jaguars are most numerous in the Amazon rainforest in South America. Agreement from any nation donating jaguars should be reciprocated by high standards for protecting the reintroduced population. Conceivably, jaguars could be captured from several populations to maximize genetic diversity. Alternately or supplementally, jaguars already held in captivity, or their cubs, could form the basis for reintroduction. In Argentina a jaguar reintroduction program breeds jaguars in captivity with no human contact. After jaguar pairs breed and cubs are born, a gate is remotely opened to enable the family to enter the wild.

19. What’s the process for this petition?

The first step is the scientific and legal petition that we’ve submitted to the secretary of the Interior and Fish and Wildlife Service. We’re hoping the agency takes this request seriously and begins a process that will include multiple opportunities for public input. We’ll continue to build support for this ambitious effort in communities in the Southwest and nationwide.

20. With limited resources for wildlife reintroduction, and with other species at greater risk of extinction, why prioritize reintroducing jaguars to North America?

The Center for Biological Diversity’s longstanding campaigns to gain legal protections for species at risk of extinction — of all taxa, from plants to fish to invertebrates — have led over time to additional (though still inadequate) resources for research into their plights and for conservation of their habitats. As an animal at the apex of the food web, the jaguar helps maintain the natural balance that sustains a host of other creatures. Moreover, reintroducing jaguars to New Mexico and Arizona — and letting them expand their range to allow movement across the U.S.-Mexico border — will help increase genetic diversity among the largely isolated jaguars in northern Sonora, Mexico, and help save them from extinction.

It’s important to note that in the 1980s, similar questions were raised regarding wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park. Today Yellowstone wolf reintroduction is a conservation milestone, and its success has in many ways rectified and even atoned for the shortsighted extermination of wolves almost a century earlier.

21. How do you know this is going to work?

Jaguars are already being reintroduced into part of their historic range in Argentina, and so far, that reintroduction has been a success. Because jaguars are cryptic, not especially vocal, and hard to locate, overall they’ll be safer from illegal shootings than other animals reviled by the livestock industry — such as Mexican gray wolves, who announce their presence through howling and often inhabit open areas. Ideally, jaguar recovery will be a cooperative endeavor of federal, Tribal and state agencies, with healthy participation from members of the public and a problem-solving approach taken by everyone.

22. How can I help?

The best thing you can do right now is add your voice to our call urging the Fish and Wildlife Service to take up our petition to reintroduce jaguars and expand its protected habitat. As the process moves along, we’ll keep you posted on how you can weigh in.

Get the latest on our work for biodiversity and learn how to help in our free weekly e-newsletter.

The Center for Biological Diversity is a 501(c)(3) registered charitable organization. Tax ID: 27-3943866.

Safari in Your Time Zone

In the brazilian wetlands, we track jaguars and hyacinth macaws on a wildlife conservation tour in the same time zone as new york city..

- Copy Link copied

Jaguar rewilding in Caiman Ecological Refuge, in Brazil’s Pantanal.

Lucas Lahargoue

We’re barely an hour into our adventure in the Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetlands contained mostly to the western edge of Brazil, when our safari guide gets the call from a nearby colleague in the bush: jaguars. Two of them, a mother and a cub. We have five minutes to gather our binoculars and our courage before clambering into the jeep, its three-tiered seats stacked high like a theater on wheels—we don’t want to miss our first sighting of the region’s apex predator.

Truth be told, I’d already had a wildlife fix that day: We had seen capybaras at the entrance to our ecotourism lodge and reserve, Caiman . Just beyond the fence—there to keep jaguars out—a lackadaisical welcoming party of oversized rodents, like guinea pigs the size of Labradors, grazed on grass and barely noted our arrival. (The closest I had ever been to capybaras before was behind a foggy glass at the San Diego Zoo, so I naturally squealed.)

Then there were the pairs of hyacinth macaws—a cousin of a parrot, stunning in their size (more than three feet long, tip of beak to tip of tail) and cobalt-blueness—in the trees above the lodge’s aquamarine pool. These striking birds of paradise often fall victim to an illegal bird trade and destruction of habitat, with an estimated 10,000 “removed from nature” by the 1980s, according to the nonprofit Instituto Arara Azul (Hyacinth Macaw Institute). But Caiman, committed to conservation, has helped to rehabilitate the species by partnering with the institute and creating an ecological refuge—part of the reason I’m here.

Casa Caiman is the childhood home of owner Roberto Klabin.

Photo by Laura Dannen Redman

My home away from home on this May safari is Casa Caiman , the actual childhood home of reserve owner Roberto Klabin. His family has ranched in the Pantanal since 1952, though they made their wealth in the pulp and paper industry. Klabin, now an entrepreneur and environmentalist, has fond memories of being at this sprawling terra-cotta estancia as far back as age 10. He doesn’t recall seeing a jaguar then, but who would, given how solitary and rare the big cat is. Rewilding efforts started in earnest in 2016, but wildfires and droughts still challenge the region’s biodiversity.

Numbers vary but the International Union for Conservation of Nature puts the total number of jaguars in the tens of thousands, making it a “near-threatened” species. More than half of the jaguars are in Brazil, and for the past 10 years, the nonprofit Onçafari has also partnered with Klabin and his Caiman Ecological Refuge to monitor and rehabilitate the mammals so they can live and breed in the natural habitat. Since 2016, three female jaguars have birthed 15 cubs, including the pair we’re tracking.