Our Organisation

Our Careers

Tourism Statistics

Industry Resources

Media Resources

Travel Trade Hub

News Stories

Newsletters

Industry Events

Business Events

Tourism statistics

- Share Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on WhatsApp Copy Link

Explore the research that Tourism Australia provides to consumers and industry.

- International statistics

- Domestic statistics

International performance

Aviation data

International tourism snapshot

International travel sentiment tracker

Domestic performance

Domestic travel sentiment tracker

Subscribe to our Industry newsletter

Discover more.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience. Find out more .

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the Traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Owners of the land, sea and waters of the Australian continent, and recognise their custodianship of culture and Country for over 60,000 years.

*Disclaimer: The information on this website is presented in good faith and on the basis that Tourism Australia, nor their agents or employees, are liable (whether by reason of error, omission, negligence, lack of care or otherwise) to any person for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking or not taking (as the case may be) action in respect of any statement, information or advice given in this website. Tourism Australia wishes to advise people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent that this website may contain images of persons now deceased.

International tourist figures still millions below pre-COVID levels as slow recovery continues

For two years, Marcela Ribeiro worked three jobs to save for her dream holiday to Australia.

Like millions of people across the globe, the 35-year-old from Brazil had long wanted to explore the country's world-famous destinations, specifically the Great Barrier Reef, World Heritage-listed rainforest and sandy beaches.

"I worked really, really hard, many jobs, to get here," Ms Ribeiro said.

"The flights were very expensive, so I have to watch everything I spend. I can't afford to eat out in the restaurants every day."

It's been a similar story for William Grbava from Canada and Amelia Mondido from the Philippines, who last week arrived in Australia for a holiday.

"It's expensive here, much more than we were expecting. We have only been able to factor in a short stop in Sydney," Mr Grbava said.

"We just had a beer and a pizza in Circular Quay for $50.

"What I really wanted to do was drive up the coast to Brisbane, through Byron Bay and those beautiful towns. That's what I did when I was younger. But with the cost of fuel and car rental, it wasn't possible."

Industry yet to recover to pre-COVID levels

It's been more than four years since Australia's borders suddenly closed to the rest of the world and became one of the most isolated destinations on the globe.

COVID-19 wreaked havoc across the country's economy, but nowhere was the pain as instant or more devastating as in the tourism industry.

In 2019, 8.7 million tourists visited Australia from overseas in an industry that was worth $166 billion.

New figures from Tourism Research Australia show there were only 6.6 million international visitors last year, a deficit of more than 2 million compared to 2019 levels.

Victoria experienced the largest loss in international visits at 33 per cent, followed by Queensland at 24 per cent and New South Wales at 22 per cent.

Nationally, Chinese visitor numbers — which made up the bulk of visitors to Australia pre-pandemic — slumped to 507,000 last year, down from 1.3 million in 2019.

Figures for the month of February show more than 850,000 people visited Australia, an increase of 257,000 for the same time in 2023, but 7.5 per cent less than pre-COVID levels.

Gui Lohmann from Griffith University's Institute for Tourism said there were a number of reasons for the slow return of international visitors.

"The airfares are significantly high and we are under an inflationary situation with labour and food costs," Professor Lohmann said.

"It could be challenging for Australia to reach above 8 million international visitors in the scenario we are in at the moment."

Professor Lohmann said cost-of-living pressures were also at play in the return of international tourists, as was a "reset" in European thinking.

"Many Europeans believe a long-haul trip is quite damaging to the environment and they're also flying less generally," he said.

"Their domestic airline routes no longer exist [and] have been replaced by train trips."

He said China's ongoing economic problems, the war in Ukraine and United States' election were also having an impact.

"It's a much more complicated world we are facing after the pandemic," he said.

A long road to recovery

Oxford Economics has forecast it could take until 2025-26 before Australian tourism returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Tourism Australia, a government agency that promotes holidays, said the strongest markets since borders reopened had been New Zealand, the United States and the United Kingdom.

"We always knew that the recovery of international travel to Australia would take time, and we have continued to see the steady return of international visitors to our shores," a spokeswoman said.

Maneka Jayasinghe, a tourism expert at Charles Darwin University, said affordability was a key factor in attracting visitors Down Under.

She said the state and federal governments should consider subsidising travel to Australia.

"Measures to reduce costs, such as discounted hotel prices, tourism package deals and food vouchers could be of importance to encourage visitors to Australia," Dr Jayasinghe said.

"Tourism operators were badly hit during COVID so may not be in a financially viable position to provide further perks to visitors, especially the small-scale operators in smaller states and territories and those operating in remote areas."

She said re-establishing links with traditional tourism markets, including Japan, was also a potential solution.

"Countries with a rapidly growing middle class, such as India, could have high potential to grow. Some of the south-east Asian countries, such as Vietnam and Indonesia, could also be attractive due to their proximity to Australia."

Dutch tourists Tim Erentsen and Laleh Maleki estimated it would cost them around $16,000 for their three-week holiday in Australia, where they are visiting Sydney, the Whitsundays and Cairns.

"It has been expensive, especially the flights," Mr Erentsen said.

Ms Maleki said the couple had travelled extensively throughout Europe and the US and the cost of hotels and food in Australia was comparable.

"We thought if we were coming all this way and spending the money to get here, we should stay a bit longer, which is adding to the cost," Ms Maleki said.

But despite that extra cost, she said the trip had been worth it.

"We love the nature, it feels very safe here. The food is so good and the people are very friendly."

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

This couple has spent months burning fuel and money to power a campsite no-one can visit.

The surprise group of people driving a resurgence of the cruise industry

- Immigration

- Rural Tourism

- Tourism and Leisure Industry

- Travel and Tourism (Lifestyle and Leisure)

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Fares fall as Australian air travel returns to pre-Covid capacity, Flight Centre says

Higher seat availability has resulted in lower airfares, group says, but cost-of-living pressures continue their impact on holiday plans

- Get our morning and afternoon news emails , free app or daily news podcast

Airlines have finally shaken off the lingering effects of Covid, with capacity back to pre-pandemic levels for the first time, according to data from Flight Centre.

Global seat availability climbed back over 100% of 2019 levels in April, with travellers enjoying lower air fares as a result.

“An analysis of key international routes for Australian travellers found fares on some international routes out of Australia dropped by up to 25%,” said Flight Centre Corporate’s managing director, Melissa Elf. “With more and more capacity and competition being introduced to the market, it’s a trend we’ll continue to see throughout the rest of the year.”

Australia’s international capacity is expected to tick up from 95% to 98% next month, while domestic capacity has been hovering between 98 and 100% for the last few months.

Elf said there are promising signs that air fares will continue to fall beyond the short term, with major carriers – including Delta, Singapore Airlines and China Southern – recently announcing new routes to Australia.

In the first quarter of 2024, flights to Australia’s most popular travel destination Indonesia were down 21% from the previous year at $798 return on average. Available seats to the holiday spot were at 115% of pre-pandemic capacity.

Sign up for Guardian Australia’s free morning and afternoon email newsletters for your daily news roundup

Capacity to Japan, Qatar and Papua New Guinea are also above pre-Covid levels, while the UK is back even. Routes to Hong Kong and the US have the biggest room for recovery, at just 63% and 70% of pre-pandemic capacity respectively.

International and domestic seat capacity across Qantas and Jetstar recovered to 90% of pre-pandemic levels in the second half of 2023, an increase of 25% on the previous year, the group said.

Despite falling air fares, rising cost-of-living pressures elsewhere are forcing more Australians to holiday within their own state or cancel travel plans altogether.

In a survey of 1,500 Australians conducted by Pure Profile for the travel industry’s peak body, 70% planned to go away for a holiday during the autumn school break, including 41% within their own state, up from 36% during summer.

after newsletter promotion

A further 21% will holiday interstate and 8% were planning to go overseas.

The Tourism and Transport Forum’s chief executive, Margy Osmond, said it was pleasing to see Australians supporting the local economy and tourism operators.

“But we’re concerned the sector is still feeling the impact of cost-of-living pressures with many families taking shorter holidays than originally planned, staying with friends or relatives to save money or recently cancelling their travel plans altogether,” she said.

Just over half of respondents said cost-of-living pressures had affected their decision to travel, with a quarter saying they would go away for shorter than originally planned as a result.

- Airline industry

Most viewed

Australia Recommends 2024

Come and Say G'day

G'day, the short film

Discover your Australia

Travel videos

Deals and offers

Australian Capital Territory

New South Wales

Northern Territory

South Australia

Western Australia

External Territories

The Whitsundays

Mornington Peninsula

Port Douglas

Ningaloo Reef

Airlie Beach

Kangaroo Island

Rottnest Island

Hamilton Island

Lord Howe Island

Tiwi Islands

Phillip Island

Bruny Island

Margaret River

Barossa Valley

The Grampians

Hunter Valley

Yarra Valley

McLaren Vale

Glass House Mountains

Alice Springs

Uluru and Kata Tjuta

The Kimberley

Flinders Ranges

Kakadu National Park

Eyre Peninsula

Karijini National Park

Great Barrier Reef

Blue Mountains

Daintree Rainforest

Great Ocean Road

Purnululu National Park

Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park

Litchfield National Park

Aboriginal experiences

Arts and culture

Festivals and events

Food and drink

Adventure and sports

Walks and hikes

Road trips and drives

Beaches and islands

Nature and national parks

Eco-friendly travel

Health and wellness

Family travel

Family destinations

Family road trips

Backpacking

Work and holiday

Beginner's guide

Accessible travel

Planning tips

Trip planner

Australian budget guide

Itinerary planner

Find a travel agent

Find accommodation

Find transport

Visitor information centres

Deals and travel packages

Visa and entry requirements FAQ

Customs and biosecurity

Working Holiday Maker visas

Facts about Australia

Experiences that will make you feel like an Aussie

People and culture

Health and safety FAQ

Cities, states & territories

Iconic places and attractions

When is the best time to visit Australia?

Seasonal travel

Events and festivals

School holidays

Public holidays

How to get to Australia's most iconic cities

How long do I need for my trip to Australia?

How to travel around Australia

Guide to driving in Australia

How to hire a car or campervan

How to plan a family road trip

How to plan an outback road trip

Uluru Aboriginal Tours, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, NT © Tourism Australia

Beginner's guide to travelling Australia

Are you ready for endless sunshine, beautiful beaches, dramatic deserts and ancient cultures? Start planning your trip with our first-timer's guide to visiting Australia.

Know before you go

Tips to start planning your trip

When is the best time to visit?

How long do I need for my trip?

Find your perfect destination.

Australian states, territories and capital cities

The complete guide to accommodation and hotels in Australia

10 Australian destinations you simply can't miss

Planning essentials.

Getting here: USA to Australia flights

Australian visa and entry requirements FAQs

Getting around

Why Australia is the best place to visit

Experience australia like a local.

A handy guide to the Australian lifestyle

Australia's bucket list food experiences

Make a booking.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience. Find out more . By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the Traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Owners of the land, sea and waters of the Australian continent, and recognise their custodianship of culture and Country for over 60,000 years.

- International (English)

- New Zealand (English)

- Canada (English)

- United Kingdom (English)

- India (English)

- Malaysia (English)

- Singapore (English)

- Indonesia (Bahasa Indonesia)

- Deutschland (Deutsch)

- France (Français)

- Italia (Italiano)

- 中国大陆 (简体中文)

*Product Disclaimer: Tourism Australia is not the owner, operator, advertiser or promoter of the listed products and services. Information on listed products and services, including Covid-safe accreditations, are provided by the third-party operator on their website or as published on Australian Tourism Data Warehouse where applicable. Rates are indicative based on the minimum and maximum available prices of products and services. Please visit the operator’s website for further information. All prices quoted are in Australian dollars (AUD). Tourism Australia makes no representations whatsoever about any other websites which you may access through its websites such as australia.com. Some websites which are linked to the Tourism Australia website are independent from Tourism Australia and are not under the control of Tourism Australia. Tourism Australia does not endorse or accept any responsibility for the use of websites which are owned or operated by third parties and makes no representation or warranty in relation to the standard, class or fitness for purpose of any services, nor does it endorse or in any respect warrant any products or services by virtue of any information, material or content linked from or to this site.

International Visitor Survey monthly snapshot

Tourism Research Australia’s monthly snapshots estimate tourism activity.

Main content

From the January 2024 reference month, TRA will return to publishing International Visitor Survey data on a quarterly basis only, with the data for December 2023 being the final monthly release.

Increased appreciation of the value of tourism data is generating significant additional demand for TRA services. At the same time, there are ongoing challenges with maintaining high quality high frequency data based primarily on survey collections. Ensuring statistical reporting remains robust and fit for purpose into the future is a priority and requires investment in the assessment and development of potential new data sources for use in tourism statistics. Statistical outputs are therefore being reprioritised to balance the timeliness of publications and the quality of releases.

International tourism December 2023

Tourism Research Australia's (TRA's) monthly snapshots estimate tourism activity in the related month. We also produce quarterly and annual international tourism results .

attach_money Spend in Australia

$2.5 billion | 95% of pre-COVID levels

person Number of trips

783,000 | 81% of pre-COVID levels

brightness_2 Nights spent in Australia

26.4 million | 98% of pre-COVID levels

Notes on the data

- This report compares the month of December 2023 with the pre-pandemic month of December 2019.

- international connections and stopovers (including airfares)

- other pre-travel or post-travel spend in the source market or elsewhere outside Australia. For example, luggage, visas, duty-free retail and ground transport.

- Unless stated otherwise, spend is reported as spend in Australia. This standard is developed using the United Nations Statistics Commission's International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008 . This defines inbound expenditure as only expenditure in the economy of reference.

Key results

International visitor spend and nights spent in Australia exceeded pre-COVID levels at 95% and 98% respectively. Trips to Australia were 81% of pre-COVID levels. The December 2023 results show international visitors:

- spent $2.5 billion during their trips

- took 783,000 international trips to Australia

- had 26.4 million nights away.

Top 4 reasons for travel

The top 4 main reasons for travel to Australia in the month of December 2023:

- This was 89% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $580 million, 100% of pre-COVID levels.

- This was 71% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $1.0 billion, 96% of pre-COVID levels.

- This was 79% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $163 million, 103% of pre-COVID levels.

- This was 83% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $601 million, 88% of pre-COVID levels.

Top 5 international visitor markets

Australia’s top 5 international markets in the month of December 2023:

- This was 86% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $174 million, 121% of pre-COVID levels.

- This was 83% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $209 million, 79% of pre-COVID levels.

- This was 85% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $216 million, 97% of pre-COVID levels.

- This was 59% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $410 million, 73% of pre-COVID levels.

- This was 101% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $140 million, 122% of pre-COVID levels.

Regional and capital city visitors and spend

In December 2023, international visitors made 729,000 trips to Australia’s capital cities.

- This was 82% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $2.1 billion, 94% of pre-COVID levels.

In December 2023, international visitors made 230,000 trips to Australia’s regional areas.

- This was 68% of pre-COVID levels.

- Spend was $425 million, 97% of pre-COVID levels.

Total spend

Total spend in December 2023 was $4.4 billion. This was 103% of pre-COVID levels.

Total spend includes purchases made overseas such as:

- international connections and stopovers (including airfares)

- other pre-travel or post-travel spend in the source market or elsewhere outside Australia. For example, luggage, visas, duty-free retail and ground transport.

Data tables

International Visitor Survey results for December 2023 compared to December 2019

- Explore data from our international and national visitor surveys using TRA Online. Find out more on our Services page.

- Read the International Visitor Survey methodology .

- Find previous reports on our Data and research page.

Contact TRA

mail tourism.research@tra.gov.au

Footer content

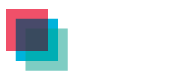

- Solar Eclipse 2024

10 Surprising Facts About the 2024 Solar Eclipse

A total solar eclipse will sweep across North America on Monday, April 8, offering a spectacle for tens of millions of people who live in its path and others who will travel to see it.

A solar eclipse occurs during the new moon phase, when the moon passes between Earth and the sun, casting a shadow on Earth and totally or partially blocking our view of the sun. While an average of two solar eclipses happen every year, a particular spot on Earth is only in the path of totality every 375 years on average, Astronomy reported .

“Eclipses themselves aren't rare, it's just eclipses at your house are pretty rare,” John Gianforte, director of the University of New Hampshire Observatory, tells TIME. If you stay in your hometown, you may never spot one, but if you’re willing to travel, you can witness multiple. Gianforte has seen five eclipses and intends to travel to Texas this year, where the weather prospects are better.

One fun part of experiencing an eclipse can be watching the people around you. “They may yell, they scream, they cry, they hug each other, and that’s because it’s such an amazingly beautiful event,” Gianforte, who also serves as an extension associate professor of space science education, notes. “Everyone should see at least one in their life, because they’re just so spectacular. They are emotion-evoking natural events.”

Here are 10 surprising facts about the science behind the phenomenon, what makes 2024’s solar eclipse unique, and what to expect.

The total eclipse starts in the Pacific Ocean and ends in the Atlantic

The darker, inner shadow the moon casts is called the umbra , in which you can see a rarer total eclipse. The outer, lighter second shadow is called the penumbra, under which you will see a partial eclipse visible in more locations.

The total eclipse starts at 12:39 p.m. Eastern Time, a bit more than 620 miles south of the Republic of Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean, according to Astronomy . The umbra remains in contact with Earth’s surface for three hours and 16 minutes until 3:55 p.m. when it ends in the Atlantic Ocean, roughly 340 miles southwest of Ireland.

The umbra enters the U.S. at the Mexican border just south of Eagle Pass, Texas, and leaves just north of Houlton, Maine, with one hour and eight minutes between entry and exit, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) tells TIME in an email.

Mexico will see the longest totality during the eclipse

The longest totality will extend for four minutes and 28 seconds on a 350-mile-long swath near the centerline of the eclipse, including west of Torreón, Mexico, according to NASA.

In the U.S., some areas of Texas will catch nearly equally long total eclipses. For example, in Fredericksburg, totality will last four minutes and 23 seconds—and that gets slightly longer if you travel west, the agency tells TIME. Most places along the centerline will see totality lasting between three and a half minutes and four minutes.

More people currently live in the path of totality compared to the last eclipse

An estimated 31.6 million people live in the path of totality for 2024’s solar eclipse, compared to 12 million during the last solar eclipse that crossed the U.S. in 2017, per NASA .

The path of totality is much wider than in 2017, and this year’s eclipse is also passing over more cities and densely populated areas than last time.

A part of the sun which is typically hidden will reveal itself

Solar eclipses allow for a glimpse of the sun’s corona —the outermost atmosphere of the star that is normally not visible to humans because of the sun’s brightness.

The corona consists of wispy, white streamers of plasma—charged gas—that radiate from the sun. The corona is much hotter than the sun's surface —about 1 million degrees Celsius (1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit) compared to 5,500 degrees Celsius (9,940 degrees Fahrenheit).

The sun will be near its more dramatic solar maximum

During the 2024 eclipse, the sun will be near “solar maximum.” This is the most active phase of a roughly 11-year solar cycle, which might lead to more prominent and evident sun activity, Gianforte tells TIME.

“We're in a very active state of the sun, which makes eclipses more exciting, and [means there is] more to look forward to during the total phase of the eclipse,” he explains.

People should look for an extended, active corona with more spikes and maybe some curls in it, keeping an eye out for prominences , pink explosions of plasma that leap off the sun’s surface and are pulled back by the sun’s magnetic field, and streamers coming off the sun.

Streamers “are a beautiful, beautiful shade of pink, and silhouetted against the black, new moon that's passing across the disk of the sun, it makes them stand out very well. So it's really just a beautiful sight to look up at the totally eclipsed sun,” Gianforte says.

Two planets—and maybe a comet—could also be spotted

Venus will be visible 15 degrees west-southwest of the sun 10 minutes before totality, according to Astronomy. Jupiter will also appear 30 degrees to the east-northeast of the sun during totality, or perhaps a few minutes before. Venus is expected to shine more than five times as bright as Jupiter.

Another celestial object that may be visible is Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks , about six degrees to the right of Jupiter. Gianforte says the comet, with its distinctive circular cloud of gas and a long tail, has been “really putting on a great show in the sky” ahead of the eclipse.

The eclipse can cause a “360-degree sunset”

A solar eclipse can cause a sunset-like glow in every direction—called a “360-degree sunset”—which you might notice during the 2024 eclipse, NASA said . The effect is caused by light from the sun in areas outside of the path of totality and only lasts as long as totality.

The temperature will drop

When the sun is blocked out, the temperature drops noticeably. During the last total solar eclipse in the U.S. in 2017, the National Weather Service recorded that temperature dropped as much as 10 degrees Fahrenheit. In Carbondale, Ill. for example, the temperature dropped from a peak of 90 degrees Fahrenheit just before totality to 84 degrees during totality.

Wildlife may act differently

When the sky suddenly becomes black as though nighttime, confused “animals, dogs, cats, birds do act very differently ,” Gianforte says.

In the 2017 eclipse, scientists tracked that many flying creatures began returning to the ground or other perches up to 50 minutes before totality. Seeking shelter is a natural response to a storm or weather conditions that can prove deadly for small flying creatures, the report said. Then right before totality, a group of flying creatures changed their behavior again—suddenly taking flight before quickly settling back into their perches again.

There will be a long wait for the next total eclipse in the U.S.

The next total eclipse in the U.S. won’t happen until March 30, 2033, when totality will reportedly only cross parts of Alaska . The next eclipse in the 48 contiguous states is expected to occur on Aug. 12, 2044, with parts of Montana and North Dakota experiencing totality.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

Industry-specific and extensively researched technical data (partially from exclusive partnerships). A paid subscription is required for full access.

Number of international visitors Sydney, Australia 2014-2023

International visitor arrival numbers to Sydney, Australia recovered significantly in the year ended December 2023, reaching over three million visitors. Nevertheless, this still remains behind the figures recorded at the peak of Sydney's international visitor economy in 2019, in which over 4.1 million international visitors took a trip to the city. During the given period, international tourist arrival numbers to Sydney plummeted to their lowest in 2021, at around 97 thousand arrivals.

Number of international visitor arrivals to Sydney, Australia from 2014 to 2023 (in 1,000s)

- Immediate access to 1m+ statistics

- Incl. source references

- Download as PNG, PDF, XLS, PPT

Additional Information

Show sources information Show publisher information Use Ask Statista Research Service

2014 to 2023

year ended December

Release date is date of access.

Other statistics on the topic

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in the UK 2019-2022

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in the UK 2019-2022

Leisure Travel

- Outbound tourism visits from the UK 2019-2022, by purpose

- Median full-time salary in tourism and hospitality industries in the UK 2023

To download this statistic in XLS format you need a Statista Account

To download this statistic in PNG format you need a Statista Account

To download this statistic in PDF format you need a Statista Account

To download this statistic in PPT format you need a Statista Account

As a Premium user you get access to the detailed source references and background information about this statistic.

As a Premium user you get access to background information and details about the release of this statistic.

As soon as this statistic is updated, you will immediately be notified via e-mail.

… to incorporate the statistic into your presentation at any time.

You need at least a Starter Account to use this feature.

- Immediate access to statistics, forecasts & reports

- Usage and publication rights

- Download in various formats

You only have access to basic statistics. This statistic is not included in your account.

- Instant access to 1m statistics

- Download in XLS, PDF & PNG format

- Detailed references

Business Solutions including all features.

Statistics on " Travel and tourism in the United Kingdom (UK) "

- Distribution of travel and tourism expenditure in the UK 2019-2022, by type

- Distribution of travel and tourism expenditure in the UK 2019-2022, by tourist type

- CPI inflation rate of travel and tourism services in the UK 2023

- Inbound tourist visits to the UK 2002-2023

- Inbound tourist visits to the UK 2019-2022, by purpose of trip

- Leading inbound travel markets in the UK 2019-2022, by number of visits

- Leading inbound travel markets in the UK 2023, by growth in travel demand on Google

- Number of overnight stays by inbound tourists in the UK 2004-2022

- International tourist spending in the UK 2004-2023

- Leading inbound travel markets for the UK 2019-2022, by spending

- Leading UK cities for international tourism 2019-2022, by visits

- Number of outbound tourist visits from the UK 2007-2022

- Leading outbound travel destinations from the UK 2019-2022

- Leading outbound travel markets in the UK 2023, by growth in travel demand on Google

- Number of outbound overnight stays by UK residents 2011-2022

- Outbound tourism expenditure in the UK 2007-2022

- Domestic overnight trips in Great Britain 2010-2022

- Domestic tourism trips in Great Britain 2018-2022, by purpose

- Number of domestic overnight trips in Great Britain 2022, by destination type

- Number of tourism day visits in Great Britain 2011-2022

- Total domestic travel expenditure in Great Britain 2019-2022

- Domestic overnight tourism spending in Great Britain 2010-2022

- Expenditure on domestic day trips in Great Britain 2011-2022

- Average spend on domestic summer holidays in the United Kingdom (UK) 2011-2023

- Number of accommodation businesses in the United Kingdom (UK) 2008-2021

- Number of accommodation enterprises in the United Kingdom (UK) 2018-2021, by type

- Turnover of accommodation businesses in the United Kingdom (UK) 2008-2021

- Turnover of accommodation services in the United Kingdom (UK) 2015-2021, by sector

- Number of hotel businesses in the United Kingdom (UK) 2008-2021

- Most popular hotel brands in the UK Q3 2023

- Consumer expenditure on accommodation in the UK 2005-2022

- Attitudes towards traveling in the UK 2023

- Travel frequency for private purposes in the UK 2023

- Travel frequency for business purposes in the UK 2023

- Share of Britons taking days of holiday 2019-2023, by number of days

- Share of Britons who did not take any holiday days 2019-2023, by gender

- Share of Britons who did not take any holiday days 2019-2023, by age

- Leading regions for summer staycations in the UK 2023

- Preferred methods to book the next overseas holiday in the UK October 2022, by age

- Travel & Tourism market revenue in the United Kingdom 2018-2028, by segment

- Travel & Tourism market revenue growth in the UK 2019-2028, by segment

- Revenue forecast in selected countries in the Travel & Tourism market in 2024

- Number of users of package holidays in the UK 2018-2028

- Number of users of hotels in the UK 2018-2028

- Number of users of vacation rentals in the UK 2018-2028

Other statistics that may interest you Travel and tourism in the United Kingdom (UK)

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in the UK 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Distribution of travel and tourism expenditure in the UK 2019-2022, by type

- Basic Statistic Distribution of travel and tourism expenditure in the UK 2019-2022, by tourist type

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in the UK 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Median full-time salary in tourism and hospitality industries in the UK 2023

- Premium Statistic CPI inflation rate of travel and tourism services in the UK 2023

Inbound tourism

- Basic Statistic Inbound tourist visits to the UK 2002-2023

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourist visits to the UK 2019-2022, by purpose of trip

- Basic Statistic Leading inbound travel markets in the UK 2019-2022, by number of visits

- Premium Statistic Leading inbound travel markets in the UK 2023, by growth in travel demand on Google

- Premium Statistic Number of overnight stays by inbound tourists in the UK 2004-2022

- Premium Statistic International tourist spending in the UK 2004-2023

- Premium Statistic Leading inbound travel markets for the UK 2019-2022, by spending

- Premium Statistic Leading UK cities for international tourism 2019-2022, by visits

Outbound tourism

- Premium Statistic Number of outbound tourist visits from the UK 2007-2022

- Premium Statistic Outbound tourism visits from the UK 2019-2022, by purpose

- Premium Statistic Leading outbound travel destinations from the UK 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Leading outbound travel markets in the UK 2023, by growth in travel demand on Google

- Premium Statistic Number of outbound overnight stays by UK residents 2011-2022

- Premium Statistic Outbound tourism expenditure in the UK 2007-2022

Domestic tourism

- Premium Statistic Domestic overnight trips in Great Britain 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Domestic tourism trips in Great Britain 2018-2022, by purpose

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic overnight trips in Great Britain 2022, by destination type

- Premium Statistic Number of tourism day visits in Great Britain 2011-2022

- Premium Statistic Total domestic travel expenditure in Great Britain 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Domestic overnight tourism spending in Great Britain 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Expenditure on domestic day trips in Great Britain 2011-2022

- Premium Statistic Average spend on domestic summer holidays in the United Kingdom (UK) 2011-2023

Accommodation

- Premium Statistic Number of accommodation businesses in the United Kingdom (UK) 2008-2021

- Premium Statistic Number of accommodation enterprises in the United Kingdom (UK) 2018-2021, by type

- Premium Statistic Turnover of accommodation businesses in the United Kingdom (UK) 2008-2021

- Premium Statistic Turnover of accommodation services in the United Kingdom (UK) 2015-2021, by sector

- Premium Statistic Number of hotel businesses in the United Kingdom (UK) 2008-2021

- Basic Statistic Most popular hotel brands in the UK Q3 2023

- Premium Statistic Consumer expenditure on accommodation in the UK 2005-2022

Travel behavior

- Premium Statistic Attitudes towards traveling in the UK 2023

- Premium Statistic Travel frequency for private purposes in the UK 2023

- Premium Statistic Travel frequency for business purposes in the UK 2023

- Premium Statistic Share of Britons taking days of holiday 2019-2023, by number of days

- Premium Statistic Share of Britons who did not take any holiday days 2019-2023, by gender

- Premium Statistic Share of Britons who did not take any holiday days 2019-2023, by age

- Premium Statistic Leading regions for summer staycations in the UK 2023

- Premium Statistic Preferred methods to book the next overseas holiday in the UK October 2022, by age

- Premium Statistic Travel & Tourism market revenue in the United Kingdom 2018-2028, by segment

- Premium Statistic Travel & Tourism market revenue growth in the UK 2019-2028, by segment

- Premium Statistic Revenue forecast in selected countries in the Travel & Tourism market in 2024

- Premium Statistic Number of users of package holidays in the UK 2018-2028

- Premium Statistic Number of users of hotels in the UK 2018-2028

- Premium Statistic Number of users of vacation rentals in the UK 2018-2028

Further Content: You might find this interesting as well

Love Exploring

The World’s Slowest Express Train and Other Mind-blowing Rail Trivia

Posted: August 18, 2023 | Last updated: December 9, 2023

Facts to send you off the rails

The US has the largest railway network

You might be surprised to hear that the US has the largest railway network in the world , and by a large margin. With a total route length over 155,342 miles (250,000km), it's two-and-a-half times longer than the second-largest network in China. It's the US freight rail network that makes up 80% of the staggering length while passenger rail, run by Amtrak, is comprised of more than 30 train routes connecting 500 destinations across 46 American states.

Glacier Express is the world's slowest express

The slowest express service in the world, Switzerland's Glacier Express takes a whooping eight hours to cover a distance of just 181 miles (291km). That's because the scenic route takes in sights like Oberalp Pass, the highest point of the journey, and the Landwasser Viaduct – a six-arch bridge which stands at 213 feet (65m) and plunges straight into a tunnel that leads through the mountain. The day-long trip covers 91 tunnels, 291 bridges and offers the chance to take in stunning alpine meadows, mountain lakes and chalets.

The steepest railway is also in Switzerland

The steepest cogwheel railway in the world , this train, ferrying passengers up to the summit of Mount Pilatus, is no mean feat. Reaching a maximum gradient of up to 48% it can be a challenging journey as it feels like the train is about to topple over at any second. The track's steep gradient is not its only spine-chilling feature. Clinging on to the mountainside, the train passes through tunnels carved into the mountain which open up to sweeping views of the surrounding landscape.

This is the longest distance you can travel by train...

Crossing two continents, the incredible journey from Porto in Portugal to Singapore is the longest you could possibly do by train alone. Covering an approximate distance of 10,000 miles (16,000km), the route leads from Porto to Warsaw in Poland before traveling east to Beijing in China. From there the journey turns south to Vietnam and reaches Singapore via Cambodia and Thailand. The full journey would cost around $7,000 and would take at least 12 days to complete.

...and the longest direct service

However, if you're after the world's longest direct train service, you'll find it in Russia. With two scheduled trains, an express departing once every two days and a regular service departing daily, the Trans-Siberian route from Moscow to Vladivostok is the longest direct train journey in the world . It covers 5,772 miles (9,289km), crosses eight time zones and takes 166 hours (144 hours on the express) to complete, which is equivalent to almost a full week. The train has 142 stops and passes through 87 cities and towns.

The longest railway tunnel is also the deepest

Gotthard Base Tunnel in Switzerland is not only the longest but also the deepest railway tunnel in the world . It runs for 35.5 miles (57km) with a maximum depth of 8,040 feet (2,450m) – that’s eight times the height of The Shard in London. The tunnel provides a high-speed link under the Swiss Alps between central and southern Europe.

Love this? Follow our Facebook page for more travel inspiration

Middleton Railway is the oldest railway still in operation

Founded in 1758, the Middleton Railway in Leeds, England operates as a heritage railway today but it was originally opened to transport coal from the Middleton pits to Leeds, which led to the city becoming a center for many developing industries. In 1812 it also became the first commercial railway to use steam locomotives successfully. Passenger services on the line didn't begin until 1969 and today visitors can still ride trains and visit the museum.

Strasburg Rail Road is America's oldest

America’s oldest operating railroad, the Strasburg Rail Road first puffed off the buffers in 1832. Today it takes its passengers on a whistle-stop tour through Pennsylvanian Amish country. Four steam locomotives still pull original rolling stock on the 45-minute round trip to and from Paradise, and an audio commentary dispenses nuggets of knowledge on the nation’s oldest continuously operating short line railway.

The busiest train station

Shinjuku Station in Tokyo, Japan is the busiest train station in the world with over 3.6 million passengers passing through daily. The station has more than 200 exits and is made up of five smaller stations. Europe's busiest is Gare du Nord in Paris, France, serving around 214 million passengers every year while Penn Station in New York City is the busiest in North America , with a thousand passengers alighting and departing every 90 seconds.

Check out these beautiful images of the world's train stations

The world's highest railway

Traveling at an extreme altitude, the Qinghai–Tibet railway is the highest line in the world , extending between Golmud and Lhasa. Just five pairs of passenger trains run along these tracks as each has to be specially equipped for high elevation. For example, the locomotives are turbocharged to combat the effects of extreme altitude, the passenger carriages on Lhasa trains have an oxygen supply for each passenger and there's a doctor on every train. The line's highest point (and also the highest in the world that can be reached on a train) is the Tanggula Pass at 16,640 feet (5,071m) above sea level.

Seven Stars is the world's most exclusive train

Japan's Seven Stars is a so-called cruise train that takes travelers on a multi-day tour around the island of Kyushu and is often considered to be among the most exclusive and expensive train journeys in the world . Bagging a ticket on this exquisite service is not as easy as just heading to the booking site – only 28 passengers travel on each journey, so prospective riders must enter a lottery to be invited to purchase a ticket for an upcoming departure.

These are the jaw-dropping rail journeys you'll never forget

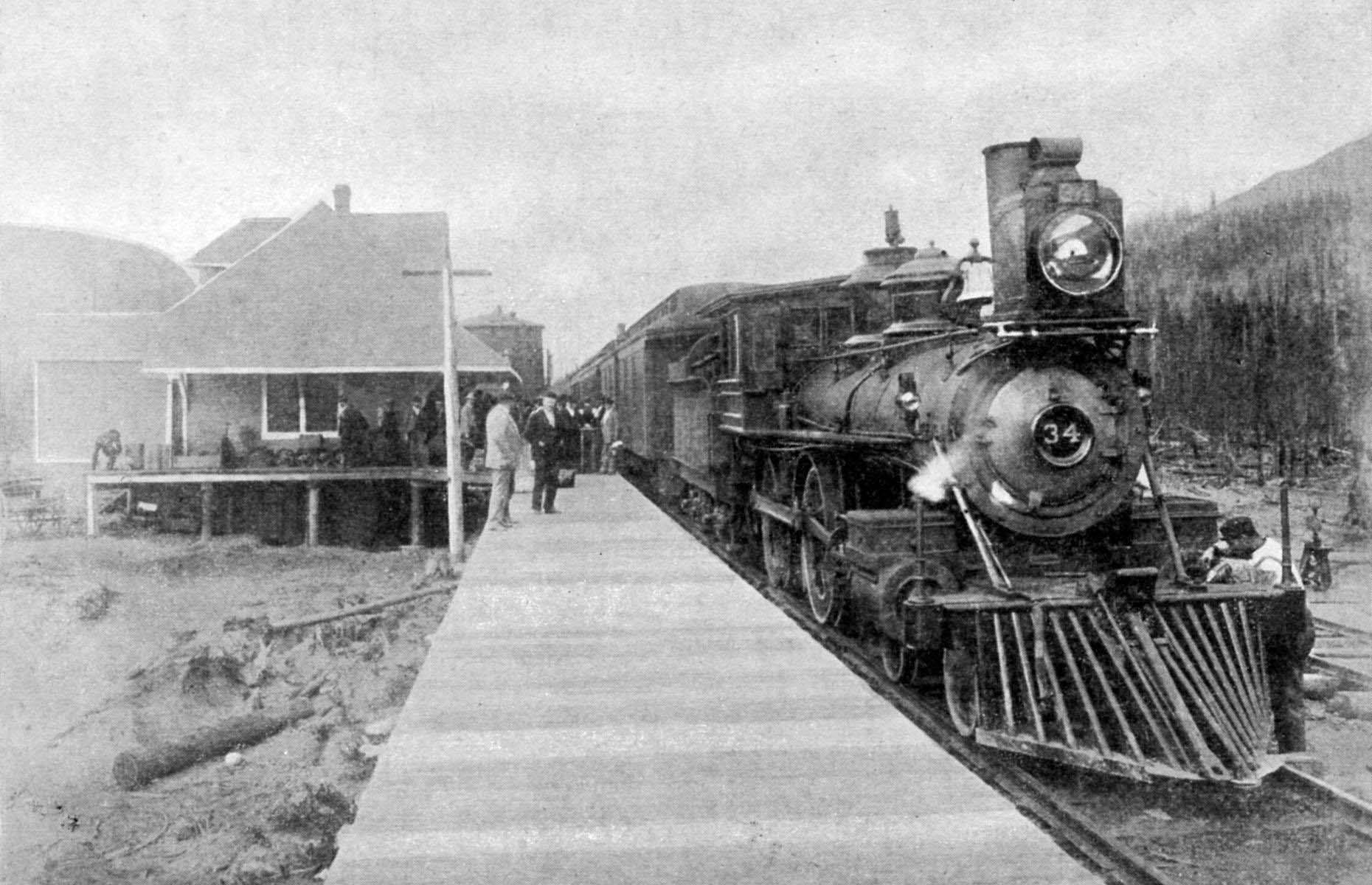

Canada's first transcontinental train

Built between 1881 and 1885, the Canadian Pacific Railway's first line connected eastern Canada with British Columbia – an incredible achievement considering the diverse landscape the train had to traverse. The first train to travel the full route departed Montreal's Dalhousie Station at 8pm on 28 June 1886 and reached the final terminus on the western seaboard, Port Moody, at noon on 4 July. Here, that first train is photographed in Fernie, some 600 miles (900km) east from Port Moody.

Take a look at incredible images that capture the history of train travel

The first train to traverse Australia

Indian Pacific travels on a very special track...

Today the trip aboard the Indian Pacific spans four days, three nights, three time zones and passes through the scenic Blue Mountains as well as across the famous Nullarbor Plain. Here the train travels on the world's longest straight stretch of railroad, which extends for 303 miles (487km).

...and stops at the most remote train station in the world

On this remarkable straight stretch of tracks you'll also find the world's most remote train station . Although Cook was once an important stopping point on the long journey across Australia, today it's more a ghost town with just four residents left. The trains still stop here to refuel and serve as a rest stop for the drivers, but if any passenger was to get off here, they would be about 62 miles (100km) from the nearest road and around 513 miles (826km) away from the nearest city.

These are Australia's eeriest abandoned towns and villages

This is the highest railway bridge in the world

Taking from 2004 to 2022 to be built, this remarkable bridge across the Chenab river in India is the world's highest . Suspended 1,178 feet (359m) above the river – that's 98 feet (30m) higher than the Eiffel Tower – the railway line crossing the bridge connects Udhampur and Baramulla. The full length of the bridge is 1,532 feet (1,315m) and will surely make for a spine-tingling ride.

You can walk across these breathtaking bridges

Can you pronounce the longest train station name?

Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch – you'll find this remarkable train station in Wales in the UK. Exactly 58 letters long, the station serves the village of Llanfairpwllgwyngyll and roughly translates as St Mary's Church in the hollow of white hazel near a rapid whirlpool and the Church of St Tysilio near the red cave in English. As it turns out, the name has no historic significance and is a marketing gimmick from the 1880s to attract tourists that stuck.

You can ride the Hogwarts Express in real life

Dubbed Britain's most scenic train route, the West Highland Line runs from the Scottish city of Glasgow to Fort William before continuing its journey towards the port of Mallaig. After a brief stop in Fort William, the train crosses the Glenfinnan Viaduct – the same bridge the Hogwarts Express crosses in the Harry Potter movies. What's more, the Jacobite Steam Train was used as the Hogwarts Express in the movies and is available to ride during the summer months (roughly April to October).

Discover beautiful train journeys that don't cost a fortune

There are ghost trains running in London

Did you know that several times a week there are empty ghost trains traveling in and out of London? Due to complicated legal procedures required to shut a railway line in the UK, it's cheaper to just run a so-called ghost train down the line every now and then. Currently, there are four services running on otherwise disused lines that don't stop or take on passengers – Overground to Battersea Park, Overground to Enfield via Stratford, Chiltern to West Ealing and Southeastern to Beckenham.

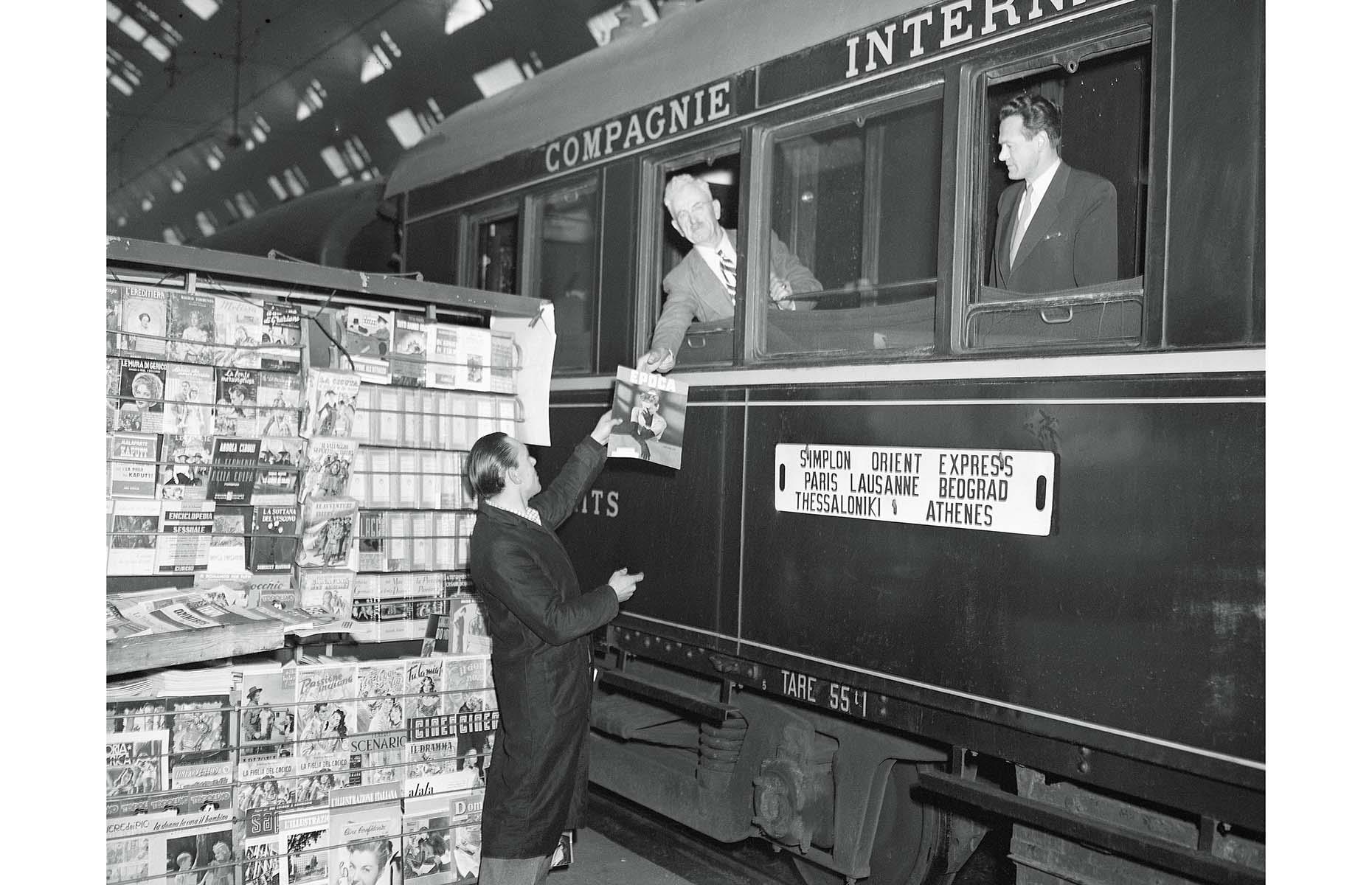

Murder on the Orient Express isn't set on the Orient Express

Bookworms and movie buffs alike might be surprised to hear that Agatha Christie's famous novel isn't exactly true to fact . By the 1920s and 1930s there was a whole host of trains connecting various European cities with Orient Express featuring in their name in addition to the Orient Express itself. The events described in the book take place on the Simplon Orient Express, which departed from Calais via Paris Gare de Lyon while the Orient Express departed Paris Gare de l'Est.

World's oldest travel agent was started thanks to a train journey

The expansion of railways in the UK is what inspired businessman Thomas Cook to create the world's first travel agent . He ran his first trip on 5 July 1841, escorting around 500 people to a teetotal rally in Loughborough from Leicester. After organizing tours of the UK and Europe for World's Fairs, Cook set up shop on Fleet Street in 1865 and began offering travel services. Pictured is a train ready to leave London Victoria on a Thomas Cook vacation to Italy in March 1937.

There are more than 20 countries without a railway network

Although many countries without a railway system are island nations (like Tonga) or among the smallest countries in the world (like San Marino) others, like Oman, Qatar and Kuwait, all lack a railway network mostly because the transport systems there are highly dominated by roads. Others like Malta and Cyprus used to have train lines, but they closed as they proved to be financially unsustainable. Iceland doesn't have a public railway system either, mostly due to harsh weather, however, plans have been made to build a high-speed airport railway.

You could go to the Moon and back on trains

There are approximately 807,783 miles (1.3 million km) of railway tracks on Earth . And while it certainly sounds like a lot, it's hard to imagine how far exactly that is. Put into perspective, the Moon is 238,855 miles (384,400km) away, which means there are enough tracks on Earth to go to the Moon and back, go to the Moon again and come back nearly halfway.

Maglev is the fastest train in the world

Traveling at a mind-boggling speed, Shanghai's maglev (magnetic levitation) train is the fastest passenger train in the world . With a spine-tingling operational speed of 267mph (430km/h), the train connects Shanghai Pudong International Airport with Longyang Road Station in the outskirts of Pudong. Traveling at an average speed of 143mph (230km/h) , the 19-mile-long (30km) journey can be completed within eight minutes.

There's a station without an entrance or an exit

A railway station in Japan exists just so passengers could get off the train and admire the stunning landscape. Located on the Nishikigawa Seiryu line in southern Japan, the Seiryu-Miharashi station has just one small platform only accessible to passengers passing through on the train. The platform looks over the Nishiki River and the surrounding forest, and the passengers have about 10 minutes to take in the views before the train leaves again.

There's a secret station hidden under the Waldorf Astoria

Hidden deep below New York’s Grand Central Station and the Waldorf Astoria, the city’s first skyscraper hotel, there is a secret train platform known as Track 61 . Although the station was allegedly used to secretly transport VIPs including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the platform was actually built as a powerhouse and storage area for unused New York Central Railroad cars and not as a passenger station.

Now take a look at more abandoned stations around the world

More for You

10 Noises Your Dog Makes—and What They Mean

Supreme Court consideration of obstruction law may not be Trump's salvation after all

10 of the biggest box office flops of all time

America pushes forward with harnessing 'limitless' supply of energy beneath our feet: 'The US can lead the clean-energy future'

The bestselling albums in music history—and no, The Beatles aren't #1

Forget sit-ups — it only takes 7 exercises and 20 minutes to sculpt a strong core

How Do I Know If My Dog Is Happy? 12 Signs of a Happy Dog

Biden's new student-loan forgiveness plan just began its 30-day public comment period — and anyone can tell the administration what they think of the relief

14 Movies That Aren’t Classified as ‘Scary’ but Still Give Us the Creeps

Donte DiVincenzo ineligible for MIP despite 81 games played

Peanuts by Charles Schulz

Ukraine May Have Just Crossed Putin's Nuclear Red Line

Here’s the one exercise our mobility coach says to do every single day

How often you bathe your dog depends on its breed

Rafael Nadal crashes out of Barcelona Open and slams 'stupid' rival

Jailed students in Massachusetts sue Department of Elementary and Secondary Education over special ed access

Top 10 Times Bill Hader Broke The SNL Cast

US Firepower Reaches 'Historic' New Location Amid China Tensions

20 animated films that viewers found super scary

Actor & Martial Artist Michael Jai White's Back Workout | Train Like | Men's Health

Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia methodology

- Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia methodology Reference Period January 2024

- Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia methodology Reference Period December 2023

- Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia methodology Reference Period November 2023

- View all releases

Introduction

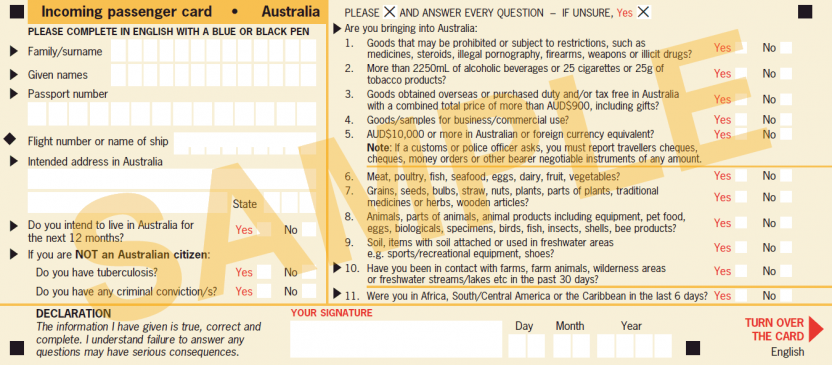

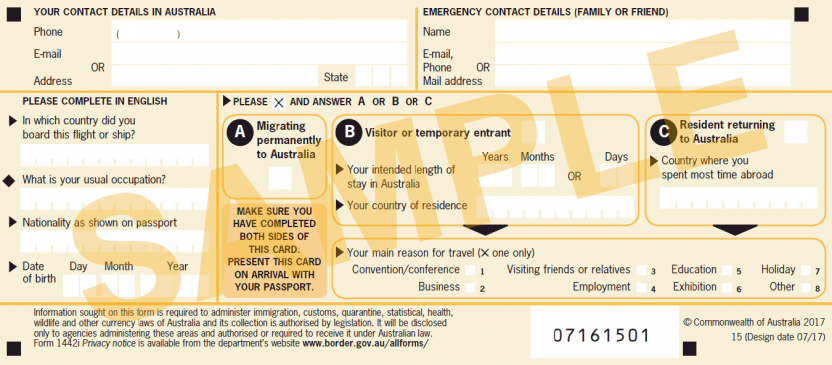

1. This page provides a reference of the various methods and changes that occur from time to time that may impact the quality of OAD statistics. Changes can be due to any part of the end-to-end processing, from passenger data collection to the output of OAD statistics. They can range from the design, provision and collection of the passenger cards through to the administrative systems and updates at Home Affairs. They can also result from better capture of passenger data, methodological improvements or improved processing systems.

Abbreviations

Classifications.

1. The classification of countries in this release is the Standard Australian Classification of Countries, 2016 . For more detailed information, refer to the ABS release Standard Australian Classification of Countries, 2016 . The entire historical series has been backcast using this version of the classification.

2. The statistics on country of residence or main destination, and country of embarkation or disembarkation have certain limitations because of reporting on passenger cards. For example many travellers just list the UK on their passenger card rather than stating England, Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland.

State and territory

1. Overseas arrivals and departures data covers Australia and its states and territories, as defined by the Australian Statistical Geography Standard 2016 . Jervis Bay Territory, the Territories of Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Norfolk Island are included as one spatial unit at the State and Territory level under the category of Other Territories.

Historical changes to the State and Territory classification

2. Following the 1992 amendment to the Acts Interpretation Act, the Indian Ocean Territories of Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands were included as part of geographic Australia. To reflect this change, another category was created, known as Other Territories which also included Jervis Bay Territory (previously included with the Australian Capital Territory). Overseas arrivals and departures data for Other Territories commenced from February 1995. 3. Norfolk Island was included in the Other Territories category from July 2017 following the introduction of the Norfolk Island Legislation Amendment Act 2015. Prior to this, Norfolk Island was an external territory and not included within geographic Australia.

Confidentiality

1. The Census and Statistics Act, 1905 provides the authority for the ABS to collect statistical information, and requires that statistical outputs shall not be published or disseminated in a manner that is likely to enable the identification of a particular person or organisation.

2. Some techniques used to guard against identification or disclosure of confidential information in statistical tables are suppression of sensitive cells, random adjustments to cells with very small values and rounding. In these cases data may not sum to totals due to the confidentialisation of individual cells.

3. The statistics in this release have been rounded to the nearest 10 to maintain confidentiality. Where figures have been rounded, discrepancies may occur between sums of component items and totals. All calculations and analysis are based on un-rounded data. Calculations made on rounded data may differ to those published.

Data sources

1. Administrative information on persons arriving in, or departing from, Australia is collected via various processing systems, passport documents, visa information, and incoming passenger cards (see Passenger card image section). Aside from persons travelling as Australian or New Zealand citizens, persons travelling to Australia are required to provide information in visa applications. These administrative data are collected by the Home Affairs under the authority of the Migration Regulations 1994 made under the Migration Act 1958.

2. ABS statistics on overseas arrivals and departures (OAD) are mainly compiled using information from Home Affairs sources. All overseas movement records are stored on Home Affairs' Travel and Immigration Processing System (TRIPS). Each month all OAD movement records and related information, including those matched to an incoming passenger card, are supplied to the ABS and then processed.

3. From July 2017, due to the removal of the outgoing passenger card, the ABS has also used Medicare enrolment data. This is a secondary source of state or territory of residence information for Australian residents and is used for a small proportion of records. For further information see ABS Privacy Impact Assessment Report 'Traveller Information and Medicare Enrolment PIA' released on the 12 September 2017.

Australian resident

For a resident returning it is someone not travelling on a temporary visa and has self identified as an Australian resident when completing an incoming passenger card. From 1 July 2007, Resident departures include all Australian citizens, permanent visa holders, and any New Zealand citizens who can be identified as a resident.

Category of travel

Overseas Arrivals and Departures data are classified according to length of stay (in Australia or overseas), as recorded by travellers on passenger cards, or derived with reference to previous border crossings. There are three main categories of movement and 10 sub-categories:

Permanent movement;

- permanent arrivals (PA)

- permanent departures (PD) - only available prior to July 2007.

Long-term movement - has a duration of stay (or absence) of one year or more;

- long-term resident return (LTRR)

- long-term visitor arrival (LTVA)

- long-term resident departure (LTRD)

- long-term visitor departure (LTVD).

Short-term movement - has a duration of stay (or absence) of less than one year;

- short-term resident return (STRR)

- short-term visitor arrival (STVA)

- short-term resident departure (STRD)

- short-term visitor departure (STVD).

A significant number of travellers on the first leg of their journey (i.e. overseas visitors on arrival to Australia) state exactly 12 months or one year as their intended duration of stay. The majority of these travellers actually stay for less than their intended duration of stay and on their departure from Australia are therefore classified as short-term movements (i.e. less than 12 months) at the second leg of their journey. Accordingly, in an attempt to maintain consistency between an arrival and the corresponding departure, and improve the quality of statistics on the duration of stay measurement, movements of travellers who report their intended duration of stay as being exactly one year automatically have their duration of stay imputed. The duration of stay of these travellers is imputed using the actual recorded duration of stay from donors who have similar characteristics from two years earlier.

- Country of birth

Country of birth refers to the country in which a person was born. For Overseas Arrivals and Departures data, the country of birth is usually collected from a traveller's passport or visa information.

Country of citizenship

Country of citizenship is the nationality of a person. For Overseas Arrivals and Departures data it is usually taken from a traveller's passport or visa information and in some cases from their passenger card.

- Country of embarkation

Country of embarkation is collected from flight information, or, for long-haul flights, from travellers' passenger cards in response to the following question:

- For someone arriving in Australia - In which country did you board this flight or ship?

Country of residence/stay

Country of residence/stay is collected from the country a traveller indicates on their passenger card.

- For overseas visitors to Australia, it is their country of residence prior to travel as recorded on their passenger card or visa.

- For Australian residents, it is the country in which they spent most time abroad (i.e. their country of stay).

Departures SmartGate system

Departures SmartGate is a secure system that automates the checks otherwise conducted by a Border Force officer at Australian airports. Departing travellers use SmartGates to self-process through passport control at Australia's International airports.

Duration of stay

The duration of stay can be accurately measured for most travellers, especially when the second leg of their journey has been completed. For visitors arriving, it is based on their intended length of stay in Australia.

Intended length of stay

On arrival in Australia, all overseas visitors are asked to state their 'Intended length of stay in Australia'.

Long-term arrivals

Long-term arrivals comprise long-term visitor arrivals (LTVA) and long-term resident returns (LTRR).

Long-term departures

Long-term departures comprise long-term resident departures (LTRD) and long-term visitor departures (LTVD).

Long-term resident departures (LTRD)

Australian residents who stay abroad for 12 months or more. For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

Long-term resident returns (LTRR)

Australian residents returning after 12 months or more overseas. For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

Long-term visitor arrivals (LTVA)

Overseas visitors who state that they intend to stay in Australia for 12 months or more (but not permanently). For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

Long-term visitor departures (LTVD)

Overseas visitors departing after a recorded stay of 12 months or more in Australia. For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

Main reason for journey

Overseas visitors/temporary entrants arriving in Australia and Australian residents returning to Australia are asked to state their main reason for journey using the following categories:

- convention/conference;

- visiting friends/relatives;

- employment;

- education; and

For any distribution, the median value is that which divides the relevant population into two equal parts, half falling below the value, and half exceeding it. Thus, the median age is the age at which half the population is older and half is younger.

Median duration

For any distribution, the median value is that which divides the relevant population into two equal parts, half falling below the value, and half exceeding it. Thus, the median duration is the duration at which half the population spent less time and half spent more time.

Overseas arrivals and departures (OAD)

Overseas arrivals and departures (OAD) refer to the recorded arrival or departure of persons through Australian air or sea ports (excluding operational air and ships' crew). Statistics on OAD relate to the number of movements of travellers rather than the number of travellers (i.e. the multiple movements of individual persons during a given reference period are all counted).

Overseas visitor

An overseas visitor is any traveller arriving to or departing from Australia who is not a resident or permanent arrival. An overseas visitor can travel for either a long-term duration of stay (12 months or more) or a short-term duration of stay (less than 12 months).

Passenger card

Passenger cards are completed by nearly all passengers arriving in Australia. Information including: country of previous residence, intended length of stay, main reason for journey, and state or territory of intended stay/residence is collected. An example of the current Australian passenger card is provided under 'Passenger card images' in the left hand side navigation bar.

Passenger card box type

Due to the removal of the outgoing passenger card from July 2017, box types D, E and F no longer exist. For further information see 2017 within the History of changes section.

a. Country of residence/stay is not collected from the passenger card for permanent arrivals. However, some information is collected from some permanent arrival visas.

Permanent arrivals

Permanent arrivals comprise:

- travellers who arrive on a permanent migrant visas for the first time;

- New Zealand citizens who indicate for the first time an intention to migrate permanently; and

- those who are otherwise eligible to settle (e.g. overseas born children of Australian citizens).

For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

Permanent visa

A visa allowing the holder to remain indefinitely in Australia's migration zone.

Port of clearance

The air or sea port where a traveller is cleared for international travel by the Australian Border Force.

See Australian resident.

Resident returns

See Short-term resident returns (STRR).

The sex ratio relates to the number of males per 100 females.

Short-term arrivals

Short-term arrivals comprise of short-term visitor arrivals (STVA) and short-term resident returns (STRR).

Short-term departures

Short-term departures comprise of short-term resident departures (STRD) and short-term visitor departures (STVD).

Short-term resident departures (STRD)

Australian residents who stay abroad for less than 12 months. For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

Short-term resident returns (STRR)

Australian residents returning after a recorded stay of less than 12 months overseas. For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

Short-term visitor arrivals (STVA)

Overseas visitors who intend to stay in Australia for less than 12 months. For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

Short-term visitor departures (STVD)

Overseas visitors departing after a recorded stay of less than 12 months in Australia. For a list of the categories see category of travel in this glossary.

State or territory of clearance

The state or territory where a traveller is cleared for international travel by the Australian Border Force. Also see port of clearance.

State or territory of residence/stay

State or territory in which overseas visitors lived/stayed or the state or territory in which residents live/lived.

On arrival, overseas visitors are asked on their passenger card for their state or territory of intended address in Australia. Residents returning to Australia are asked on their passenger card for their state or territory of intended address.

Temporary entrants

See temporary visas.

Temporary visas

Temporary entrant visas are visas permitting persons to come to Australia on a temporary basis for specific purposes. Main contributors are tourists, international students, those on temporary work visas, business visitors and working holiday makers.

Permission or authority granted by the Australian government to foreign nationals to travel to, enter and/or remain in Australia for a period of time or indefinitely.

Visa applicant type

Under the Migration Regulations 1994, there are two types of applicants - primary and secondary applicants.

The primary applicant is generally the person whose skills or proposed activities in Australia are assessed by Home Affairs as part of their visa application. They will usually have been specifically identified on the application form as the 'main applicant'.

A secondary applicant is a person whose visa was granted on the basis of being a family member (e.g. spouse, dependent child) of a person who qualified for a primary visa. They will have been identified on the visa application as an 'other' or secondary applicant with the person who met the visa criteria being specifically identified on the visa application as the 'main applicant'.

Visa group - permanent family visas

Persons who have arrived in Australia on a Child, Partner, Parent or Other Family stream visa. These migrants are selected on the basis of their family relationship (spouse, de facto partner, intent to marry, child, parent, other family) with their sponsor who is an Australian citizen, permanent resident, or eligible New Zealand Citizen.

Visa group - permanent other visas

Includes humanitarian and refugee visas as well as all other permanent visa holders.

Visa group - permanent skilled visas

Those categories of the Migration Program where the core eligibility criteria are based on the applicant's employability or capacity to invest and/or do business in Australia. The immediate accompanying families of principal applicants in the skill stream are also counted as part of the skill stream.

This definition of skill stream is used by Home Affairs who administer the Migration Program.

Visa group - temporary other visas

Includes other temporary visas not already stated.

Visa group - temporary student visas

These are overseas students who undertake full-time study in a recognised educational institution.

Visa group - temporary skilled visas

Includes Temporary Work (Skilled) (subclass 457) visa holders who were permitted to travel to Australia to work in their nominated occupation for their approved sponsor for up to four years as well as the Temporary Skill Shortage (TSS) visa (subclass 482).

Visa group - temporary visitor visas

A visitor is any traveller arriving to or departing from Australia who is not a resident. A visitor can be either short-term (less than 12 months) or long-term (12 months or more). Visitor visa holders are non-permanent entrants to Australia whose visa is for tourism, medical treatment, short stay business or visiting relatives.

Visa group - temporary work visas

Known as Working Holiday Makers visa and includes subclasses 417 and 462. Permits young adults from countries with reciprocal bilateral arrangements (with Australia) to undertake short term work or study while holidaying in Australia.

Visitor arrivals - short-term trips

See Short-term visitor arrivals (STVA).

History of changes

July 1998, permanent departures.

1. Prior to July 1998, the number of overseas-born (excluding NZ) permanent departures of Australian residents was overstated.

2. In July 1998, Home Affairs introduced a box type validation edit to the processing system. The edit checked and corrected the box type according to the Visa Class/subclass. With the exception of Australian and NZ citizens, only Australian residents departing permanently (Box F) who hold permanent visas were retained in this box type. For temporary visa holders who incorrectly ticked Box F, their box type was changed to visitor or temporary entrant departing (Box D).

July to December 1998, reason for journey

3. Before the introduction of the redesigned passenger card in July 1998, 5% of short-term visitor arrivals, on average, were recorded as having a reason for journey of 'Other' or 'Not Stated'. This percentage rose to 14% for July, 16% in August and 29% in September 1998 as a result of processing problems. These problems were addressed by Home Affairs, with the percentage of 'Other' and 'Not Stated' dropping to 8% and 7% in October and November respectively.

4. From January 1999, OAD statistics referencing these three months have been revised. The revised data were calculated by estimating the number of persons responding 'Other/Not Stated' using past trends for each country of citizenship and proportionally allocating any persons in excess of the estimated 'Other/Not Stated' total amongst the remaining categories.

July to December 1998, state or territory of residence/stay

5. For the months of August 1998, September 1998 and October 1998, data entry problems experienced by Home Affairs caused an overstatement of the Northern Territory as the main state of stay with a corresponding understatement for the remaining states and territories. In November 1998 these numbers returned to levels more comparable with previous years, with Home Affairs indicating that they had instigated data quality procedures to address this issue.

6. From January 1999, OAD statistics referencing these months have been revised. The revised data were calculated by estimating the number of persons indicating the Northern Territory as their main state of residence/stay using past trends and proportionally allocating any persons in excess of these estimates amongst the remaining states and territories.

7. With the introduction of the new processing system from July 2001, Home Affairs started providing the ABS with data on all missing values for state or territory of residence/stay. From July 2001 to Jun 2004, any missing state or territory of residence/stay were imputed using category of movement and state of clearance.

September 1998, age, country of birth, citizenship and sex

8. A problem was experienced in the processing of OAD data for movement dates between 6 September 1998 and 16 September 1998 following the introduction of changes to Home Affairs' input processing system. This problem may affect around 10% of all September 1998 records used in estimation and result in incorrect details for citizenship, date of birth, sex and country of birth.

September 1999, China and Hong Kong

1. September 1999 overseas arrivals and departures data were revised for movements to and from China and Hong Kong for three variables: country of birth, country of citizenship and country of residence/stay. Changes to 'country of birth' and 'country of citizenship' have been made from data supplied by Home Affairs. Changes to 'country of residence/stay' have been made by assuming the average proportion of country of birth to country of residence/stay for migrants from China and Hong Kong in September 1995 to September 1998.

New Zealand - permanent arrivals or residents

1. Under the Trans-Tasman Agreement, New Zealand (NZ) citizens are not required to have a visa to travel to Australia. As a result, on their arrival in Australia, visa documentation cannot be used to determine whether they are either a permanent migrant or a temporary visitor, or an Australian resident returning from NZ. Analysis undertaken by Home Affairs suggests that a substantial proportion of NZ passport holders tick Box A (migrating permanently to Australia) each time they arrive in the country, causing an overcount of NZ migrants entering Australia. The following edits were applied to arrival movements to correct the overcounting of NZ migrants.

2. From July 2001 to June 2002, Home Affairs coded all NZ citizen arrivals who had ticked Box A (migrating permanently to Australia) and had been to Australia previously (based on Home Affairs records) to residents returning (Box C). However, if these people were visitors previously, this recoding had the effect of incorrectly reducing the number of NZ migrants whilst at the same time incorrectly increasing the number of NZ citizen who were returning residents. This problem was overcome by coding the NZ citizens who had been changed by Home Affairs from Box A to Box C back to Box A.