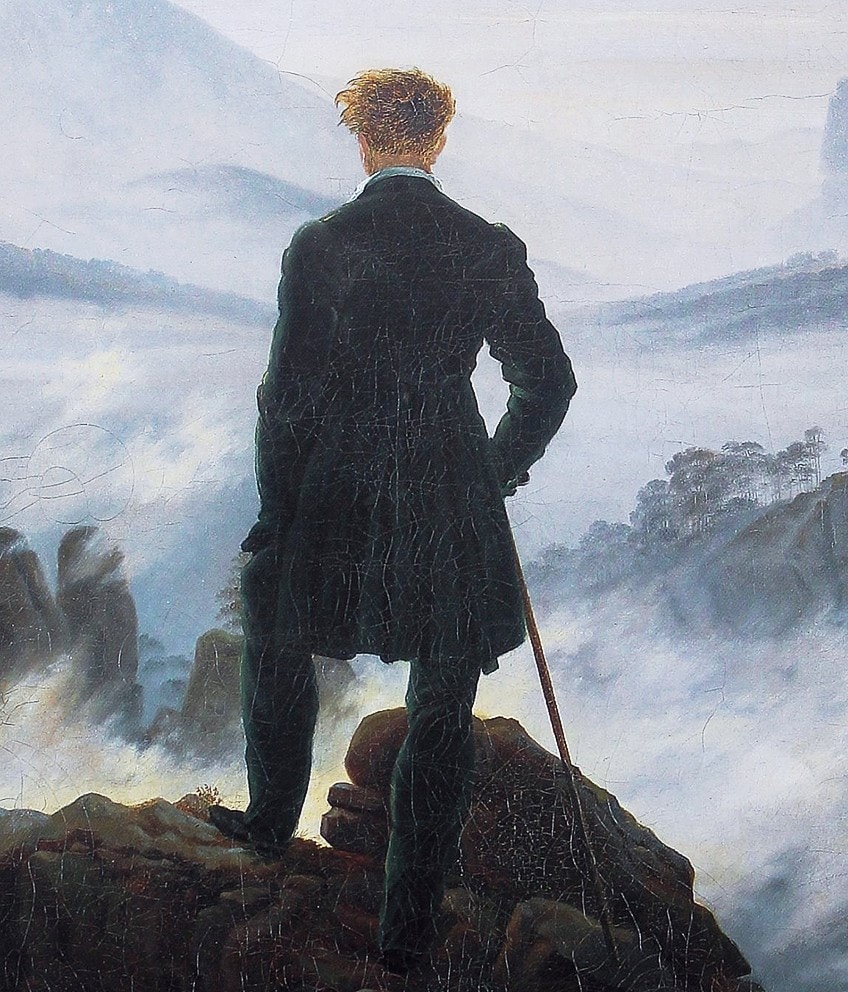

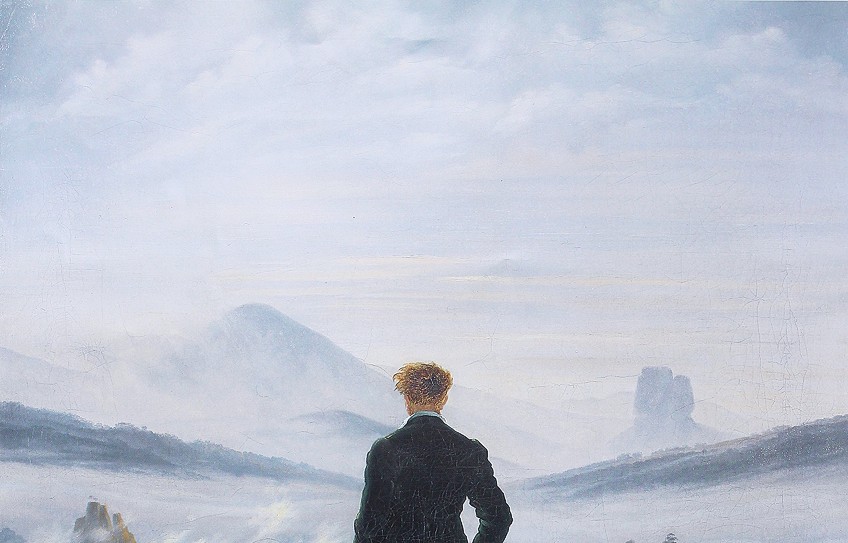

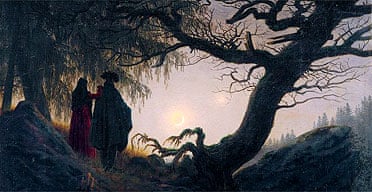

A Closer Look at Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich

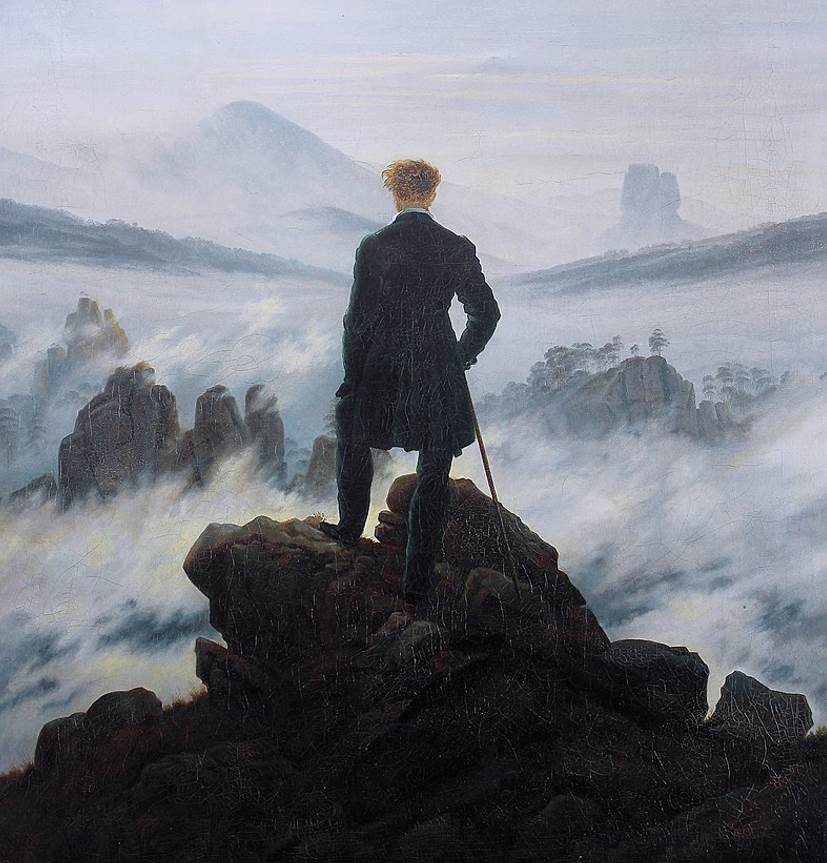

In this post, I take a closer look at Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich. It is an iconic work of Romanticism that features a man standing on the edge of the rocky terrain, looking out over the foggy landscape. I cover:

Key Facts and Ideas

Color and light, composition, key takeaways, want to learn more, thanks for reading.

(Before diving into this post, make sure to pick up a copy of my free Landscape Painting Starter Kit .)

- It is also referred to as Wanderer Above the Mist or Mountaineer in a Misty Landscape .

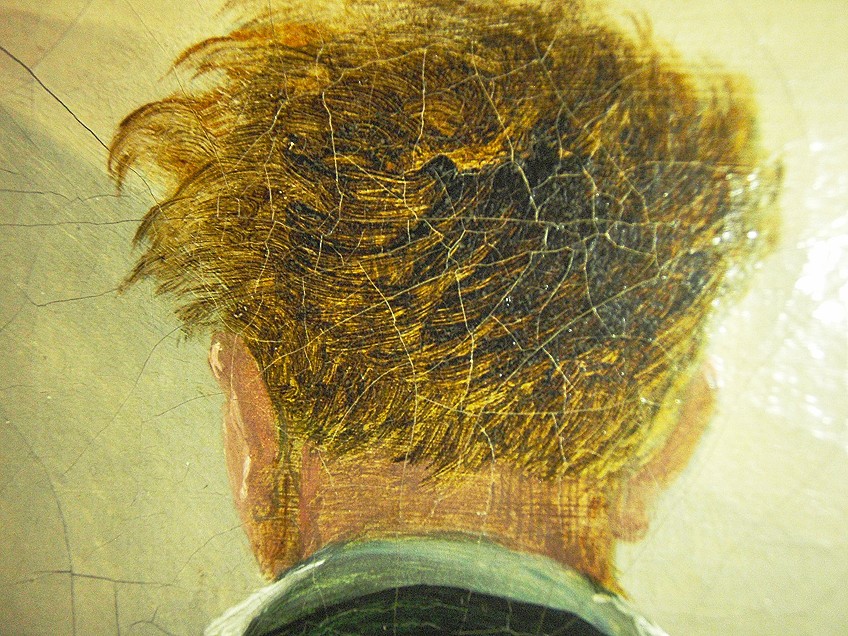

- The identity of the man is uncertain. Some have suggested it is a self-portrait of the artist himself, pointing to similarities in appearance, such as the red hair. Historian Joseph Koerner provides a more likely interpretation that it is a certain individual, Colonel Friedrich Gotthard von Brincken. In his book, Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape , he writes:

“Von Brincken was probably killed in action in 1813 or 1814, which would make the 1818 Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog a patriotic epitaph”. Via Sothebys

- The landscape is based on the Elbe Sandstone Mountains in Saxony and Bohemia. It is not an exact depiction of the landscape, rather an amalgamation of various parts. Friedrich would travel the mountains and create sketches. Then, back in the studio, he would construct his own interpretation of the landscape.

- It is considered an iconic work of Romanticism , which is characterized by a deep appreciation of nature.

The sun is the primary light source. The silhouette of the foreground suggests it is overhead and out in front.

The clouds and fog seem to be diffusing the light, meaning it is not a strong and direct light like the midday sun on a clear day. This is considered to be a “good” light to paint under, as it provides enough light for you to clearly see all the colors, but not so much as to wash the colors out. (I provide a cheat sheet on how to paint under different types of light in my Landscape Painting Starter Kit ).

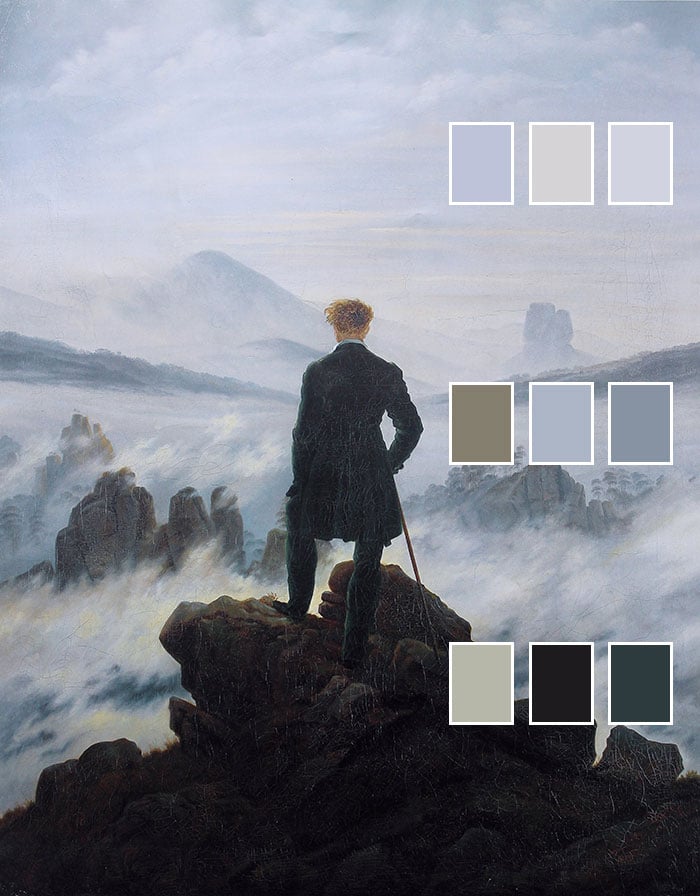

The colors are restrained, with mostly weak blues, pinks, and yellows. The painting relies much more on value contrast (the contrast between light and dark elements) than hue or saturation contrast. Refer to the grayscale image of the painting below.

As you can see, there is a sharp contrast between light and dark elements. This is because most of the colors are at the extremes of the value scale (the colors are either really light or really dark; there are hardly any mid-tones).

Notice how the darks represent the man, rocks, and other “solid” objects; whilst the lights represent the clouds, sky , and fog. So not only is there a contrast between light and dark, but also between solid and transient.

The values in the painting also get gradually lighter as you recede into the distance, starting with the dark, imposing rocks in the foreground, and ending with the barely visible mountains in the background. The colors also get a touch cooler in temperature . This creates a sense of atmospheric perspective or depth.

Unlike most landscape paintings, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog has portrait dimensions (taller than it is wide). This reiterates the upright stance of the man around the center.

The stance of the man is an important feature of the painting in and of itself. He is leaning primarily on one leg and there is a slight shift in his body to counter this. This is known as contrapposto , which is Italian for “opposite” or “counter”. It is considered a natural and visually pleasing stance (think about what the painting would look like if he was standing straight and rigid).

Most of the painting is taken up by negative space (sky, clouds, and fog). But, there is a sense of balance against the small but powerful areas of positive space (rocks, trees, and man).

Another interesting observation is the open plane of the composition . Other than the foreground at the bottom, there is no use of framing. This helps convey the vastness of the landscape.

In this painting, hard edges are used for the rocks in the foreground and the man. This gives a sense of clarity and closeness. Much softer edges are used for the transient fog, clouds, and sky.

Notice how all the edges get softer as you recede into the distance, yet the relationships stay intact. By relationships, I mean how hard one edge is compared to another.

For example, if you look at the foreground, the edges used for the rocks are harder than the edges used for the fog.

Now, look at the distant mountains. In general, this area is much softer than the foreground. But, the relationships are the same-the edges of the mountains are harder than the fog, clouds, and sky.

The key point here is that relationships matter , much more than the absolute hardness of an edge.

I also draw your attention to the different techniques Friedrich used to alter the hardness of the edges.

One technique is gently blending one color into the next. This softens the edge between two color shapes. The more the colors are blended, the softer the edge.

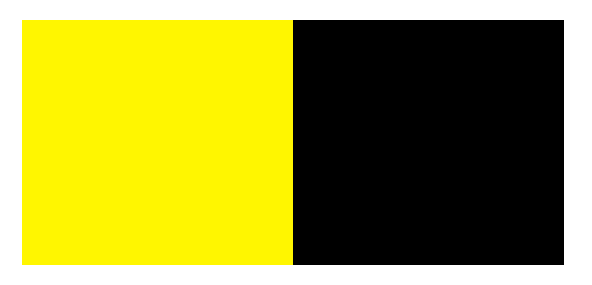

The other technique relies on the use of contrast, in particular, color contrast. The idea is this: the sharper the contrast between two shapes, the harder the edge. For example, take the following two shapes:

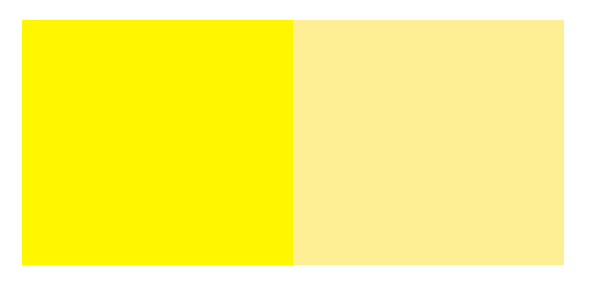

The contrast is sharp and the edge is hard. Watch what happens if I reduce the color contrast between the two shapes.

The transition between the two colors is just as abrupt, but the edge appears much softer.

Below are two more examples using colors from the painting. The first with colors from the foreground-a sharper contrast and a harder edge. The second with colors from the background-a weaker contrast and a softer edge.

- You are not limited to painting only what you see. You can always mix and match different parts to create your own unique composition like Friedrich did in this painting.

- The perspective of the painting has a powerful influence on the focal point. Despite the man being positioned center stage in this painting, the main focus appears to be the vast landscape. We get a chance to see what the man is seeing.

- The light on an overcast day is “good” light to paint under, as it tends to be diffused and balanced.

- You can use color gradations to give a sense of atmospheric perspective.

- A large area of “quiet” negative space can be balanced against a small area of “active” positive space.

- Edge relationships matter, much more than the absolute hardness of the edges.

You might be interested in my Painting Academy course. I’ll walk you through the time-tested fundamentals of painting. It’s perfect for absolute beginner to intermediate painters.

I appreciate you taking the time to read this post and I hope you found it helpful. Feel free to share it with friends.

Happy painting!

Draw Paint Academy

About | Supply List | Featured Posts | Products

Dan Scott is the founder of Draw Paint Academy. He's a self-taught artist from Australia with a particular interest in landscape painting. Draw Paint Academy is run by Dan and his wife, Chontele, with the aim of helping you get the most out of the art life. You can read more on the About page .

35 comments on “A Closer Look at Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich”

Excellent, really helpful. Thanks

Very interesting and informative. Thank you

Great article Dan. Very informative and thought provoking Thank you

Thanks ever so much for all your valuable hits. I genuinely appreciate it.

You are always worth reading. You make me think. Thank you.

This is a particularly helpful and interesting post. Many points to follow up and practice. Thank you

I always look forward to your emails and tips. Credit information and I learn from it every time.

This overview, like so many of your pointers, takes me a long way toward understanding what my own paintings are about. There is so much yet to know if I want to create a good painting intentionally. It makes me appreciate it very much to discover I occasionally succeed accidentally. Thanks so very much for helping us all along!

Very helpful and insightful!

So much important information here. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks for the lesson on contrapposto.

This really made me go back and study the painting. I hope I can make use of the valuable information.

You draw my attention to so many different elements and explain them so simply. Thank you.

Wow! I am learning so much and gaining enthusiasm for art! Thank you so much!

Great analysis. I enjoyed…..and learned a lot. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you, Dan, for your inspirational analysis of this painting. I have been grappling with inserting a human figure in the foreground of a snowy winter landscape. I now see a way through to doing it!

I have never seen this painting before but you made it come alive for me. Thank you for the analysis and the painting tips.

Dan, sempre fico esperando seus e-mails sobre as análises de pinturas. Gostaria que você fizesse uma análise de uma pintura de Vermeer. Obrigado

Really appreciate the takeaways.

Dan thanks for pointing out how to compose and look at the colors. I am not a painter at all but I pay more attention in the real life nature and see what you just brought out.

Very clear and concise! Thank you for the wonderful post!👍👏🏼

Loved this painting and I have learned from it because of your walking me thru it

Hi Dan, I like this work, even without the figure it is a nice study in painting scenery. Including my arch nemesis “ROCKS”. Another success story from the Start cott vault. Thanks, Dave M.😎🇦🇺

Ii appreciate this type of newsletter. It’s different and informative. Thank you for it!

I love these…you’ve shown things I wouldn’t have noticed.

Very helpful, thank you.

So helpful. Struggling with edges and this explains the technique. Thank you

Valuable insights . Thank you.

Can’t go over value and contrast too much. Thanks Dan

Thank you for this thoughtful post. I found the discussion of the human pose as integrated into the more dominant landscape very useful!

This beautiful& romantic painting helps set the mood for Valentine’s Day this upcoming Friday. Thanks!

Thank you once again.

That was really nice, thank you! I would just add that this genre of painting used the landscape as a symbol for spiritualism and added elements of Greek and Roman influence. That specific contraposto stance symbolized virtue and extreme spirituality during the Renaissance.

Hi As I have never formally studied art I am finding your analyses of art fascinating. Thanks heaps!

Thank you so much for this post! It was really well written and helpful for studying this painting.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Ampersand Gessobord: My Detailed Review and Why I Prefer It Over Canvas

December 11, 2023

A Closer Look at View of Auvers-sur-Oise—La Barrière by Paul Cézanne

June 2, 2023

Claude Monet – Master of Color and Light

September 20, 2021

A Closer Look at Vincent van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night

March 26, 2021

A Closer Look at Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val D’Ognes by Marie Denise Villers

January 5, 2022

How to Paint Hair and Fur

November 28, 2022

“Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818) by Caspar David Friedrich has become an iconic painting depicting the depths of solitude. It is one of the finest examples from the German Romantic art movement and the one that we will discuss in more detail in this article.

Table of Contents

- 1 Artist Abstract: Who Was Caspar David Friedrich?

- 2.1.1 The Man and His Outfit: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog Meaning

- 3.1 Visual Description: Subject Matter

- 3.2 Color, Value, and Light

- 3.3 Texture

- 3.4 Line, Form, and Shape

- 3.5 Space

- 4 In the Presence and Precipice of Greatness

- 5.1 Who Painted Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog?

- 5.2 When Was Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog Made?

- 5.3 Where Is Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog?

Artist Abstract: Who Was Caspar David Friedrich?

Caspar David Friedrich was born on 5 September 1774 and died on 7 May 1840, in Germany in the town of Greifswald. In his early years, he studied under Johann Gottfried Quistorp at the University of Greifswald and was introduced to various other notable artists and ideas around nature and God.

He attended the Copenhagen Academy from 1794 to 1798, after which he relocated to Dresden. He became popular for his landscape paintings that were deeply rooted in aspects of the sublime and spiritual. In Friedrich’s personal life, he experienced numerous deaths of family and friends, and he was remembered as a solitary person.

His artworks influenced many other art styles like Surrealism, Symbolism, and Abstract Expressionism. He was also admired by Adolf Hitler.

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818) by Caspar David Friedrich in Context

Below we will provide a brief contextual analysis exploring the Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog meaning. In German this painting is titled Der Wanderer Über Dem Nebelmeer . We will then provide a formal analysis, discussing the subject matter and Friedrich’s artistic approaches in terms of the art elements like color, texture, line, form, and space, which all set the tone for an ambient and deeply moving subject.

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

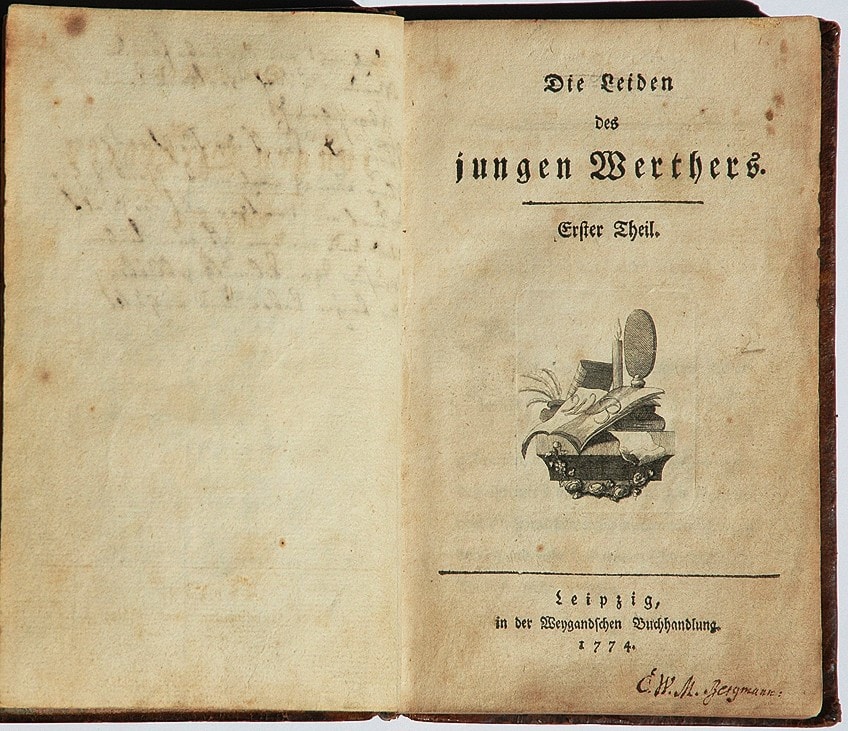

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich was painted during the early 1800s, at a time in Europe when Romanticism was a prevailing style in arts and culture, ranging from literature, visual arts, and music. It was believed that the earlier Sturm und Drang movement was a precursor to the Romantic movement.

Sturm und Drang was a German movement, meaning “Storm and Stress”, active during the latter half of the 1700s. The importance of this movement was the emphasis on emotion and self-expression, and it is commonly described as “subjective”.

It was most prevalent in music and literature and received its name from the Sturm und Drang (1777) play by Friedrich Maximillian Klinger. Additionally, the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was a leading proponent of the movement and became widely known for his publication The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774).

This novel greatly influenced Romanticism, which developed afterward. Romanticism was also categorized as more emotive and subjective and moved away from the intellectualism that came from preceding movements like Neoclassicism during the mid-1700s.

It is important to note that Romanticism developed across European countries like France, Germany, England, and Spain. For the purposes of our article, we will focus on German Romanticism, providing a context for Caspar David Friedrich’s artworks.

In the spirit of freedom, German Romanticism sought self-expression that celebrated the majesty of nature, and landscape art became a conduit for this expression. Furthermore, it was not solely the depiction of nature, but the deep bond between man and nature, veering on the subliminal.

The Man and His Outfit: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog Meaning

The question, “When was Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog made?” is an important one to explore, as we have done briefly above. However, its date points to pertinent periods in history that influenced its meaning, such as the Napoleonic Wars, the impacts of the French insurgency in Germany, and the socio-political aspects that ensued as a result of these.

The figure in “Der Wanderer Über Dem Nebelmeer”, according to some art history sources, could have been Caspar David Friedrich himself, based on the red hair color.

Other scholars, like Joseph Koerner, believe the man could have been Colonel Friedrich Gotthard von Brincken and that this painting was a sort of “patriotic epitaph” created for him after his death. This touches on Friedrich’s preoccupation with the political climate during the early 19th-century, and that he was a German Nationalist, hinted at by the figure’s outfit, which is reminiscent of what is referred to as Altdeutsche Tracht , meaning “’ Old German costume”.

These outfits were commonly worn by Germans during this period as statements against the Napoleonic Wars, which were prevalent in Europe from 1799 to around 1815. This costume, in short, symbolized a sense of nationalism against the invading French.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

Below we will discuss a formal analysis of Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich, first describing the painting and its subject matter and then the artist’s style in terms of several art elements like color, texture, line, form, and space, among others, and how they impact and determine the overall artistic unity of the composition.

Visual Description: Subject Matter

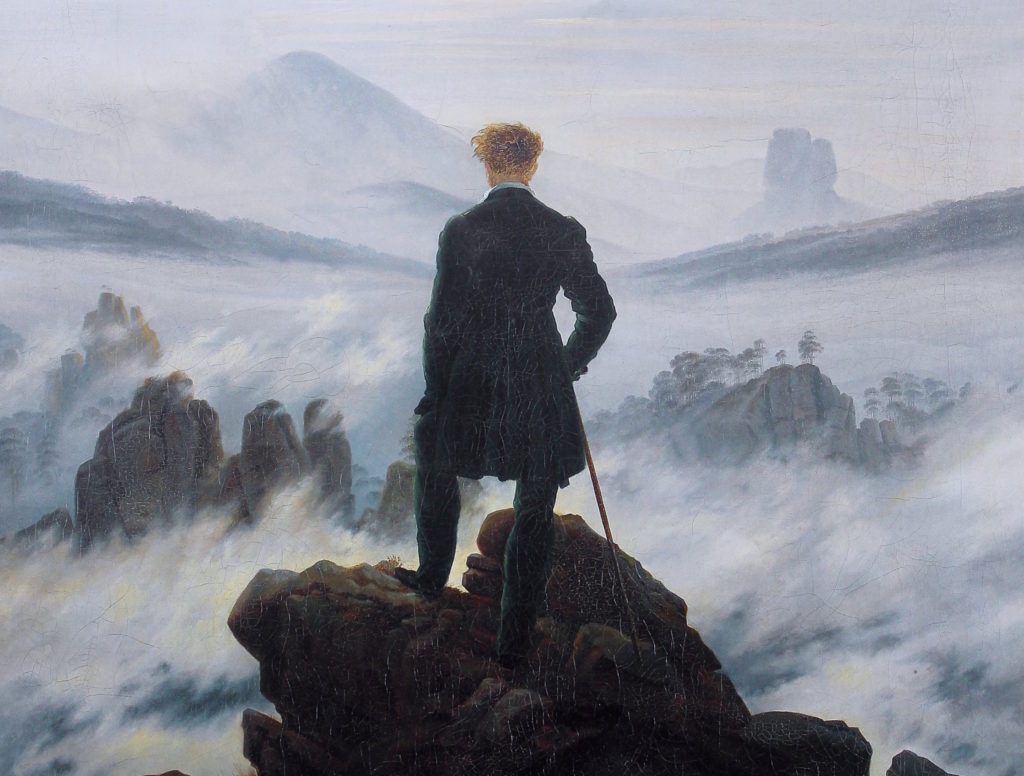

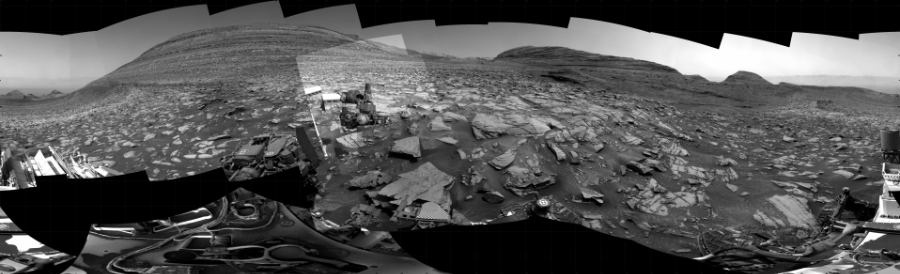

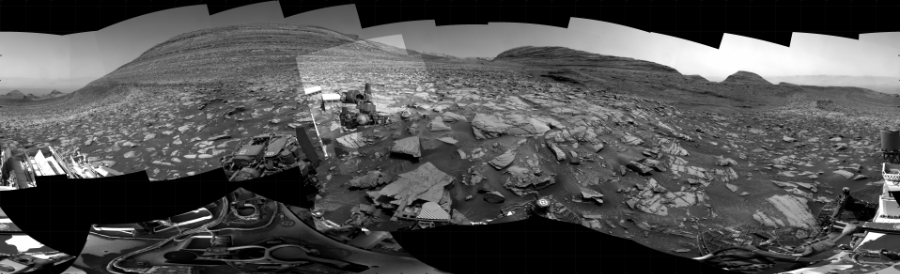

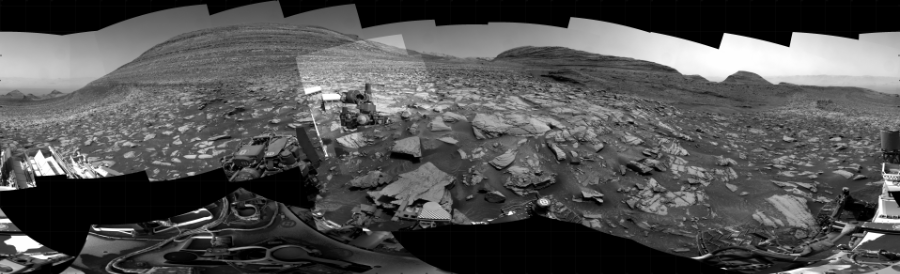

In the first third and foreground of the painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, we see a solitary figure standing on the edge of a protruding rock formation. He looks out over a vast, foggy, landscape of what appears to be a mountainous region in the far distance, in the background of the composition.

An interesting fact about this landscape is that Friedrich reportedly depicted the Elbe Sandstone Mountain region. This mountain range is between Saxony in Germany and Bohemia in the Czech Republic.

Furthermore, Friedrich apparently made sketches of the mountain ranges while he was there in person and repainted certain ranges from his visual documentation. Therefore, it is possibly not the exact depiction of the mountain ranges and their placements. The man stands with his back to us, the viewers, which is a common technique, otherwise referred to as “compositional strategy/device”, that Caspar David Friedrich utilized to depict his figures.

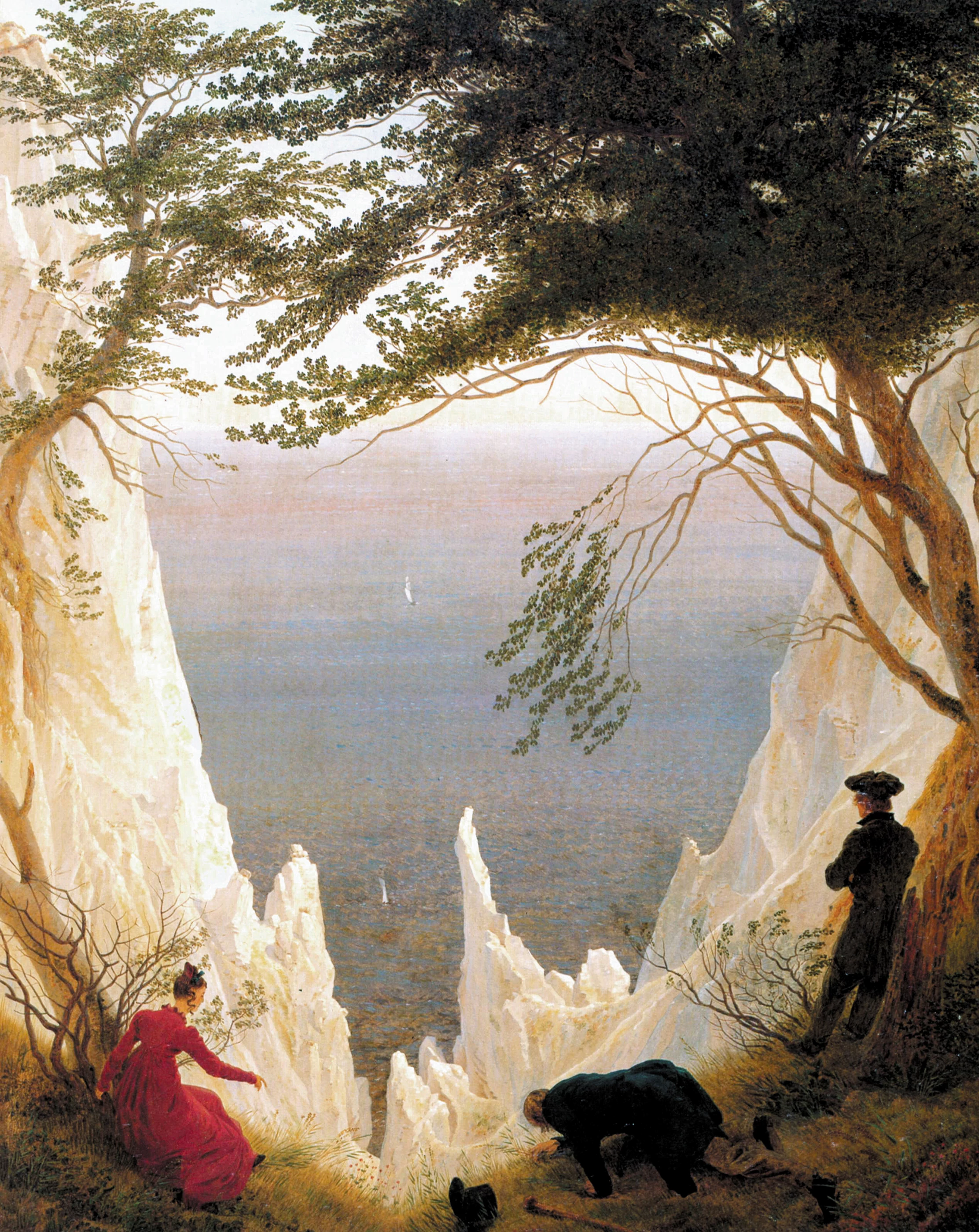

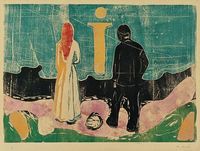

This technique is known as Rückenfigur , which is the German word for “figure from the back”. It is also evident in some of Friedrich’s other paintings, for example, The Monk by the Sea (1808 – 1810), Two Men by the Sea (1817), and Woman at a Window (1822).

In the middle-ground, there are more rocky ridges protruding through their misty veil, right in front of this lonely wanderer. Some of the rocky tops also have trees on them and we can notice what appears to be a canopy of trees also peeping through the misty veil.

The upper third of the composition is composed of the sky above, filled with white clouds that seemingly become part of the mist that covers the mountains in the distance, blanketing the rest of the scenery in the foreground. There is almost a sense of motion and aliveness here as the mist moves inwards and outwards.

If we look at the man, he is wearing an overcoat that has been described as dark green in color. His red hair is short and appears windblown. He is holding a walking stick in his right hand and his left hand seems to be resting on the upper part of his left leg, which is slightly bent and propped up on the rocky promontory, stabilizing his posture as he stands; his right leg is straight.

Color, Value, and Light

If we look at artistic elements like color and value, Friedrich utilized whites, pinks, and blues for the sky above and darker colors for the rocks in the foreground as well as dark green for the man’s coat. The painting’s value consists of a notable contrast between light and dark in this composition.

The foreground is dark, and the background is light. Value is an art element that refers to how light or dark a color appears and is often demonstrated on a grayscale. It also adds highlights to an image, which gives it more color harmony .

In “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog”, we see there is a darker area of color in the foreground, we can say about a third of the composition, and the background, or two-thirds of the rest of the composition, appears lighter.

Furthermore, there is an implied, natural, light source from the sun, although we cannot directly see it because of the mist and clouds. The man is facing this light, which creates a contrasting effect from the way the light falls.

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog is filled with a texture that sets this landscape scene. The best examples include the way Friedrich painted the mist and clouds, which appear like white wisps throughout the upper two-thirds of the composition.

There is an implied texture of lightness, air, and fleetingness here, furthermore, creating a rhythm and movement to the scene.

Additionally, Friedrich also created an implied texture in all the rocky regions, for example, the rocks in the foreground on which the man stands. These have a rougher and craggy texture compared to the mist and fog, which creates another contrasting effect.

Line, Form, and Shape

There is a focus on vertical lines in this composition, notably the figure standing upright and looking out over the horizon. This is a clear shape in our view compared to the other shapes in the distance formed by the fog and mountains.

These shapes are less distinct and appear hazier, further highlighting the man in the foreground.

In the middle ground, there are two horizontal lines created by the surrounding mist and hillside landscape. These appear to converge in the center, almost creating a focal point in the distance and seemingly bringing our focus onto the man in the foreground.

Space

Space is an important aspect of this composition. Friedrich depicted a vast landscape, achieved through highlighting, contrasting, and converging colors, textures, and various lines and shapes. These all create the illusion of three-dimensional landscape space, or depth, we see in front of us.

This depth is further created by what is known as “ atmospheric perspective ”, which is the hazy effect of the landscape in the distance, as well as the scale implied by the figure in the foreground compared to the background.

Space as an art element also includes positive and negative space. Positive space is created by the subject of the composition, and here it would be the figure and the rocky areas in the foreground. Negative space includes the space around the primary subject, which would be the mist and clouds.

In the Presence and Precipice of Greatness

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog is over 200 years old, still impacting modern-day viewers, reminding us of age-old truths that seemingly go beyond being human. Even in our contemporary times, this painting has made its way into popular culture, inspiring film posters, adorning book covers, and becoming a popular motif on items like T-shirts.

Friedrich’s artworks even became tokens of appreciation and propaganda for the German Adolf Hitler. This association marred Friedrich’s reputation as an artist, however, his reputation was eventually restored within the art world.

“Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich depicts a man face-to-face with the vastness of nature, and ultimately, God. He is truly in the presence of greatness, and as we look at him looking at the landscape, even possibly contemplating his life and nature, we are similarly face-to-face with this landscape, contemplating our own place in this magnitude. We too, stand on the precipice of greatness.

Take a look at our Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who painted wanderer above the sea of fog .

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818), also titled Der Wanderer Über Dem Nebelmeer , was painted by the German artist Caspar David Friedrich. It became one of the most popular German Romanticism paintings.

When Was Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog Made?

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich is dated 1818, which was during European art history when art styles shifted from Neoclassicism to Romanticism. This painting, also called Der Wanderer Über Dem Nebelmeer , has been categorized as German Romanticism.

Where Is Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog ?

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818) is housed at the Kunsthalle art gallery in Hamburg, Germany. It was received by the gallery and made part of the collection around 1970.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich.” Art in Context. May 22, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/wanderer-above-the-sea-of-fog-by-caspar-david-friedrich/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 22 May). “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/wanderer-above-the-sea-of-fog-by-caspar-david-friedrich/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich.” Art in Context , May 22, 2022. https://artincontext.org/wanderer-above-the-sea-of-fog-by-caspar-david-friedrich/ .

Similar Posts

“Narcissus” by Caravaggio – Painting of Narcissus Analysis

“Joan of Arc” Painting by Jules Bastien-Lepage – A Formal Analysis

“View of Toledo” El Greco – Analyzing the “Vistas de Toledo” Painting

“Wild Poppies Near Argenteuil” by Claude Monet – An Analysis

“Nymphs and Satyr” by William-Adolphe Bouguereau – Ethereal Art

“Madonna With the Long Neck” – Francesco Mazzola’s Masterpiece

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

The wanderer above the sea of fog

The wanderer above the sea of fog is a Romantic Oil on Canvas Painting created by Caspar David Friedrich in 1818 . It lives at the Kunsthalle Hamburg in Germany . The image is in the Public Domain , and tagged Seascapes . Download See The wanderer above the sea of fog in the Kaleidoscope

Where is the Wanderer?

Friedrich described his approach to landscape painting saying “The artist should paint not only what he has in front of him but also what he sees inside himself.” Friedrich brought this practice to the Wanderer, splicing together a variety of landscapes from the Elbe Sandstone Mountains in Saxony, that he'd previously sketched in person. The distant mountain peak to the left of the figure resembles either the Kaltenberg peak in Austria or the Růžovský vrch, the Rosenberg mountain. Below the mountain a fingered rock craig looks like the million-year-old Bastei rock formation. The strange, vertical pillar in the far distance to the right of the figure is based on the Zirkelstein, a table hill topped by a 130ft tall sandstone rock on the border between Switzerland and the Czech Republic. Below the Zirkelstein is the Gamrig, a rock formation that overlooks the village of Waltersdorf. Even the rocks the titular wanderer stands on was pulled from nature. The boulder’s dramatic silhouette inspired by the jagged sandstones atop the Kaiserkrone , or “imperial crown” another table hill near the Zirkelstein.

Reed Enger, "The wanderer above the sea of fog," in Obelisk Art History , Published May 11, 2016; last modified November 06, 2022, http://www.arthistoryproject.com/artists/caspar-david-friedrich/the-wanderer-above-the-sea-of-fog/.

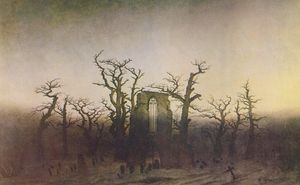

Abbey among Oak Trees

The Life Stages

Mountain with Ascending Mist

Moonrise over the Sea

The Slave Ship

Northern Lights

The Card Game

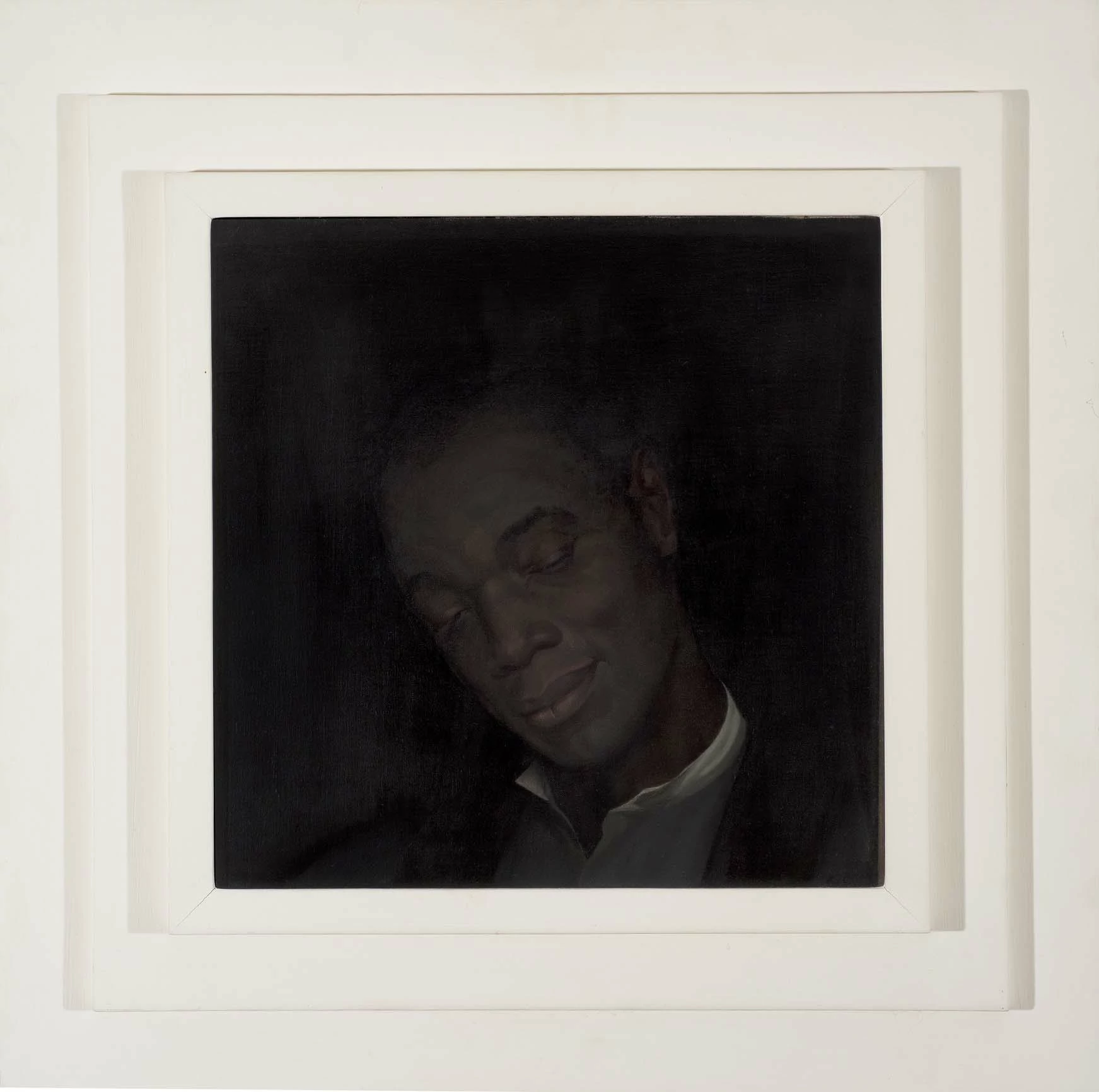

Spiritual (Study of a Negro Head)

Madonna and child with the infant saint john the baptist.

The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis

Chalk Cliffs on Rügen

The Raft of the Medusa

By continuing to browse Obelisk you agree to our Cookie Policy

Caspar David Friedrich

- Chalk Cliffs on Rügen

- Cross in the Mountains

- Cross in the Mountains c. 1806

- Graveyard Under Snow

Landscape with Temple Ruins

- Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon

- Monastery Graveyeard in the Snow

- Moonrise Over the Sea

- Morning in the Riesengebirge

- Seashore by Moonlight

The Abbey in the Oakwood

- The Cross Beside The Baltic

- The Cross in the Mountains

- The Giant Mountains

- Two Men Contemplating the Moon

Two Men Contemplating the Moon c.1819

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

- Winter Landscape With Church

- Landscape with Grave Coffin and Owl

- Date of Creation:

- Alternative Names:

- Wanderer Above the Mist, Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer

- Height (cm):

- Length (cm):

- Art Movement:

- Romanticism

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Hamburg, Germany

- Displayed at:

- Hamburger Kunsthalle

- Wanderer above the Sea of Fog Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Related Paintings

- Bibliography

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog Story / Theme

Elbsandsteingebirge, Germany

Some believe Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog to be a self portrait of Friedrich. The young figure standing in contemplation has the same fiery red hair as the artist. The figure stands in contemplation and self reflection, mesmerized by the haze of the sea fog as if it were a religious and spiritual experience. He wonders in that moment about the unforeseen future. By placing his back toward the viewer he is not shutting them out - rather he enables them to see the world through his own eyes, to share and convey his personal experience. Though some believe this to be a self-portrait tradition recounts that the figure in Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog is a particular person, a high-ranking forestry officer, Col. Friedrich Gotthard von Brincken, of the Saxon infantry. He wears the green uniform of the volunteer rangers, those called into service against Napoleon by King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia. As this man was most likely killed in 1813 or 1814, this painting may also serve as a patriotic tribute. Though Friedrich painted this scene in his studio, he sketched it at the place of inspiration, Elbsandsteingebirge, in Saxony and Bohemia. He was always greatly inspired by German landscape and deeply moved of the beauty he found in his homeland. He depicts the mountains, the trees, and the heavy mist above the sea.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog Analysis

Friedrich executes a unique composition and employs his famous technique in Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. His use of color and lighting is also notable. Composition: Friedrich chose to paint this landscape vertically instead of the much seen horizontal orientation. The upright position of the canvas models the uprightness of the figure in the painting. Use of technique: Once again Friedrich employs the Ruckenfugen technique in which he paints the figure with his back towards the viewer. This makes the figure something of a mystery to the viewer - they are unsure what he is thinking or his reaction to the landscape that they too are taking in. By separating the figure and the viewer, the latter focuses more on the beauty of the surroundings rather than the man's role in nature. Color palette: For this composition Friedrich uses a slightly brighter palette than usual. He mixes blues and pinks across the sky with the mountain and rock in the distance echoing these colors. He paints the figure in a dark green coat - typical German attire. Use of light: The light seems to be coming up from beneath the rock, somehow illuminating the fog. The rock the mysterious figure stands on remains mostly in silhouette form, though some detail is visible at the top near the figures' feet. Tone elicited: As the viewer cannot see the figure's face, the tone is questionable. In line with Friedrich's other works, and the overall Romantic ideal, it seems fitting to believe that this wanderer stands in awe of the spooky nature before him. His poise is one of a confident man, he leans on his cane, and a relaxed hand rests in his pocket.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog Related Paintings

The Lonely Ones, Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch

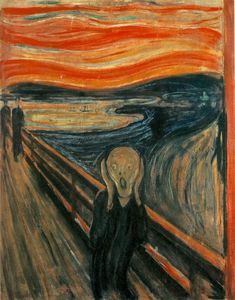

Edvard Munch, The Lonely Ones, 1899: Friedrich influenced only a few artists that followed him. Among his admirers was Symbolist painter Edvard Munch whose work has been explicitly related to Friedrich's. Munch could identify with Friedrich's representative landscapes and in this work a clear reference is seen to Friedrich's Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon . Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893: This is another landscape reference that occurs with Friedrich's Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. Both paintings illustrate the "halted traveler" where the solitary figure experiences an epiphany in the middle of nature. Both artists rejected the traditional horizontal orientation of most landscapes and instead employ a vertical orientation, showing the upright presence of the character. The major differences between the two paintings is that Friedrich's figure, Rückenfigur, keeps his back turned on the viewer while Munch's figure confronts the viewer directly. The viewer then engages with the figure and less attention is paid to the landscape, an ideal crucial to the Romantic artists. Munch also displays a hostile landscape, showing the opposite of the Romantics' linking of humankind and God through nature.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog Artist

Friedrich very rarely included people in his landscape paintings. He painted Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog just around the time more figures started appearing in his work. Some historians believe it is because he got married right around this time, which may have invoked some newfound appreciation for human life and human relations. Like the majority of his work, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog was not fully appreciated during its day. It wasn't until after his death that Wanderer gained significant attention. This is because Friedrich was, for the most part, misunderstood in his time. As an artist, he struggled to gain full comprehension from the public and critics of his time, but he continued to paint according to his own artistic convictions, not for approval. He experienced a significant amount of success during his high days, even being commissioned by the Russian royal family. Thanks to his intense and emotional focus on nature, Friedrich changed the style of landscapes and became a key member of the Romantic Movement. Friedrich helped shaped the movement while in its fledging stage, his personal ideals matching up perfectly with the new art form. Neoclassical artists focused on properly accounting history through close attention to detail while Romantic artists flirted with themes of man's part in nature, divinity found in nature, and emotion. Although many critics are still unable to comprehend Friedrich's allegorical references to Christ and God through landscape, today his work is generally well respected.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog Art Period

Unlike most artists, Caspar David Friedrich took less inspiration for the great masters of art before him and paid more attention to the teachers of his formal education. Consequently, Friedrich had a truly unique style; he could transform landscapes from a mere forest to a wooded wonderland where each branch symbolized something greater, something deeper. The trees were no longer just trees, but beautiful wooden creatures that represented the unwavering strength of Christ. The rays of the sun didn't just serve to illuminate the ground but to show the light of the Holy Father. Romanticism was an art period lasting approximately form the early 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century. Romantic artists flirted with themes of man's self glorification, man's part in nature, divinity found in nature, and emotion. Caspar David Friedrich fits in ideally with the characteristics of Romanticism as he displayed individualism, subjectivity, spirituality and the love of nature. Unfortunately, reception of Friedrich's work deteriorated as he aged. Eventually even his patrons lost interest in his work as Romanticism was being replaced with new, modern ideals. Friedrich died while his art was no longer wanted. Critics thought it too personal to understand, completely disregarding the fact that that was what made the work so original in the first place. However, Symbolist and Surrealist artists, such as Max Ernst, took note of the allegorical meanings that saturated Friedrich's canvases and both groups came to reference Friedrich as a great source of inspiration and foundation for their perspective movements.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog Bibliography

To find out more about Friedrich's contribution to Romanticism please choose from the following recommended sources. • Barber, John. The Road from Eden: Studies in Christianity and Culture. Academica Press, LLC, 2006 • Bèorsch-Supan, Helmut. Caspar David Friedrich. Thames & Hudson, 1974 • Boime, Albert. Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, 1815-1848. University of Chicago Press, 2004 • Hoffman, Werner. Caspar David Friedrich. Thames & Hudson, 2001 • Jensen, Jens Christian. Caspar David Friedrich: life and work. Barron's, 1981 • Koerner, Joseph Leo. Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape. Yale University Press, 1990 • Wintle, Justine. Makers of Nineteen Century Culture: 1800-1914. Routledge, 2002 • Wolf, Norbert. Caspar David Friedrich: 1774-1840: The Painter of Stillness. Taschen, 2003

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

- Caspar David Friedrich

* As an Amazon Associate, and partner with Google Adsense and Ezoic, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, or Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer , to give it it's original German title, is the most famous painting from the career of German Romanticist painter, Caspar David Friedrich. It was finished in 1818 and now resides at the Kunsthalle Hamburg in Hamburg, Germany.

"...Close your physical eye, so that you may see your picture first with the spiritual eye. Then bring what you saw in the dark into the light, so that it may have an effect on others, shining inwards from outside..."

The style of this painting is instantly recognisable as the work of Friedrich, with a foreground figure superimposed against a stunning landscape scene. This style of composition helps the viewer to feel very much a part of the painting which was one of the strengths of this famous German painter. Landscape scenes of Germany continued throughout his career but not always with a figure in the foreground, despite that though, it remains very much a signature of his career. It is common for artists to become famous for just one artwork, despite having produced so much during their lifetime and Friedrich can be considered inseparable to Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. It has also been promoted to be considered one of the finest contributions to the entire Romanticist movement.

In this memorable artwork there is a flurry of mist that drifts across the landscape as the key figure stands tall, looking down on this mountainous setting. He is smartly dressed, suggesting he holds a powerful position but the way in which his back is turned to the viewer, and that we cannot see his face, leaves a mysterious element to this painting. Who is he? What is he doing? The viewer is left to debate what appears before their eyes. We have included a larger image of the painting at the bottom of this page so that you can appreciate even more of the detail added by artist Friedrich.

The figure in this scene is dressed in a smart overcoat, coloured dark green (you may not be able to make out this colour in the photograph), and holds a brown walking stick in his right hand. This suggests age and experience, but he holds it at an angle which oozes strength and confidence. His hair is untidy, suggesting that the wind has unsettled an otherwise groomed individual. He cares not, for his focus is entirely taken by the mass of fog that sweeps across the landscape in front of him. The rocks on which he stands are darkened, allowing the rest of the scene to drift into the correct perspective, with a greater brightness. It also helps to focus the eye on the gentleman in the foreground. He also wears a shirt below his coat and also solid boots which give a picture of comfort and confidence within these challenging conditions.

Artist Friedrich separates the scene into three or four sections, altering the level of brightness on each one in order to build this sense of perspective. Beyond the initial foreground where the dark figure stands in awe, there is then immediately in front of him another section of rock with trees that dots out from above the clouds. There is some vegetation, but generally the scene is of a relatively barren environment, deep into the tall mountains. This section dots jutting shapes vertically up to the sky right across the canvas. Most is partially covered by fog, but a few rocks of the left hand side can be seen without any impediment.

Perhaps due to the perils of translations, this German painting is sometimes given different names in English, beyond the generally accepted name of Wanderer above the Sea of Fog which we have defaulted to. Others have referred to this piece as Wanderer above the Mist or Mountaineer in a Misty Landscape. Whatever the disagreement, the image itself remains the artist's signature artwork and also a key highlight in the achievements of the European Romanticist movement. Other notable members of the group included the likes of Eugene Delacroix, who gifted us the likes of Liberty Leading the People , Death of Sardanapalus and Christ on the Sea of Galilee , as well as British landscape painter JMW Turner who is most famous for The Fighting Temeraire .

Whilst being a major highlight in the collection of the Kunsthalle Hamburg in Germany, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog stands alongside several highly significant paintings including the likes of Madonna by Edvard Munch , Jacob Restaurant by Max Liebermann, Revolution of the Viaduct by Paul Klee , Phryne before the Areopagus by Jean-Léon Gerome and Nana by Edouard Manet . You will also find contributions from the Old Masters, such as Francisco de Goya, Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens, Jacob Isaacksz van Ruisdael and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

Article Author

Tom Gurney in an art history expert. He received a BSc (Hons) degree from Salford University, UK, and has also studied famous artists and art movements for over 20 years. Tom has also published a number of books related to art history and continues to contribute to a number of different art websites. You can read more on Tom Gurney here.

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) Is a Romantic Masterpiece, Evoking the Power of the Sublime">Why Caspar David Friedrich’s Painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) Is a Romantic Masterpiece, Evoking the Power of the Sublime

in Art , History | January 8th, 2024 4 Comments

When Caspar David Friedrich completed Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer , or Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog , in 1818, it “was not well received.” So says gallerist-Youtuber James Payne in his new Great Art Explained video above , which focuses on Friedrich’s most famous painting. In the artist’s lifetime, the Wanderer in fact “marked the gradual decline of Friedrich’s fortunes.” He withdrew from society, and in 1835, “he suffered a stroke that left the left side of his body effectively paralyzed, effectively ending his career.” How, over the centuries since, did this once-ill-fated painting become so iconic that many of us now see it referenced every few weeks?

Friedrich had known popular and critical scorn before. His first major commission, painted in 1808, was “an altarpiece which shows a cross in profile at the top of a mountain, alone and surrounded by pine trees. Hard for us to understand now, but it caused a huge scandal.” This owed in part to the lack of traditional perspective in its composition, which presaged the feeling of boundlessness — overlaid with “rolling mists and fogs” — that would characterize his later work. But more to the point, “landscape had never been considered a suitable genre for overtly religious themes. And of course, normally the crucifixion is shown as a human narrative populated by human figures, not Christ dying alone.”

It’s fair to say that Friedrich did not do things normally, both philosophically — breaking away, with his fellow Romanticists, from the mechanistic Enlightenment consensus about the world — and aesthetically. The Wanderer ( further analyzed in the Nerdwriter video just below ) presents a Weltanschauung in which “landscape was a representation of a divine world order, and man was an individual who watches, contemplates, and feels much more than he calculates and thinks.” To achieve his desired effect, Friedrich assembles an imagined vista out of various elements seen around Dresden, presenting it in a manner that combines characteristics of both landscapes and portraits to “create a powerful sense of space” while directing our attention to the lone unidentified figure right in the center.

The “curious combination of loneliness and empowerment” that results is key to understanding not just the priorities of the Romantics , but the very nature of the aesthetic sublime they reverently expressed. To be sublime is not just to be beautiful or pleasurable, but also to exude a kind of intimidating, even fearsome vastness; how it feels to enter the presence of the sublime can never be fully replicated, let alone explained, but as Friedrich demonstrates, it can effectively be evoked. Hence, as Payne points out, the tendency of current media like movie posters to crib from the Wanderer , in service of the likes of Dunkirk , Oblivion , Into Darkness , and After Earth . Determining whether those pictures live up to the ambitions evident in Friedrich’s artistic legacy is an exercise left to the reader.

Related content:

An Introduction to the Painting of Caspar David Friedrich, Romanticism & the Sublime

The Otherworldly Art of William Blake: An Introduction to the Visionary Poet and Painter

How the Avant-Garde Art of Gustav Klimt Got Perversely Appropriated by the Nazis

Brian Eno on Creating Music and Art As Imaginary Landscapes (1989)

Great Art Explained: Watch 15 Minute Introductions to Great Works by Warhol, Rothko, Kahlo, Picasso & More

Based in Seoul, Colin M a rshall writes and broadcas ts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities , the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema . Follow him on Twitter at @colinm a rshall or on Facebook .

by Colin Marshall | Permalink | Comments (4) |

Related posts:

Comments (4), 4 comments so far.

Stewart Lee’s rumination on the Wanderer

https://youtu.be/Dz9Nad0bxDU?si=9GAMR530KEQHrOjP

I’m interested

Thank you for this very informative video. Casper David Friedrich’s work is intriguing. With as much thought as he gave to his paintings, if he would have journaled, it may have answered many questions. One wonders how an artist’s mind in working as he paints. Again, thank you for illuminating video. A new, old artist to ponder.

Visited the Friedrich exhibit at the Hamburg museum last week and was so in awe of this amazing work. This helps me understand the artist and his time. Thank you for the education!

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Receive our newsletter!

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Access and Info for Institutional Subscribers

Created by Jacob Gibson on Mon, 03/15/2021 - 18:40

Description:

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog , by Caspar David Friedrich depicts a man standing on a rocky cliff face looking out over a landscape obscured by fog. It was painted in 1818 and is representative of Romantic era artwork. When we examine the painting, the middle third is dominated by the Wanderer and the rocks he stands upon, with the adjacent two thirds devoted to the obscured landscape. We've talked about concepts of space in class, and it's significant that so much space in this painting is devoted as equally to an obscure landscape as it is to the Wanderer if not more so. And yet there is a definite sensation we get while looking at this painting that draws the eye and is a sensation we can almost feel in our bones.

The artist puts this into words by saying "A picture must not be invented, it must be felt" (Prodger 90). Friedrich was known for his depiction of landscapes, and this could very well be inspired by or be a real depiction of one. But the artist says that isn't the point. Critics say that we should look at his landscapes not as "decipherable symbols but as carriers of sensation" (90), and that Friedrich didn't want to just faithfully reflect the landscape, "but rather to reflect his soul" (90). This approach to art is definitely reflective of the Romantic era in that so many of the ideas we get from them are so self conscious and self reflective, often using nature as a catalyst for that introspection. We can see evidence of this in the painting because the landscape itself is obscured by fog, while the man isn't. We see only his back, and the viewer gets the impression that for such a thoughtful pose coming from this Wanderer, that contemplation is taking place, but perhaps not merely that over the wonder of the details of the view. " It appears, thus, that Friedrich sought not merely to explore the blissful enjoyment of a beautiful view but rather to have an encounter with the spiritual Self through the contemplation of nature (Gaete 61).

While researching this painting, I kept thinking about "The Thorn" by William Wordsworth. In that poem, Wordsworth uses a focused point of view to establish the landscape around the thorn, before slowly zooming out, giving us more and more details until we can see how human and emotional this all is. It's an exploration of a genuine human experience (albeit a painful one), depicted through the lens of a landscape. I argue that Friedrich is doing something similar here with point of view in this painting. The way that the landscape is depicted here makes sure that the viewer will see how human this painting is. BUT, I don't believe this would happen if Friedrich wasn't able to make good on his desire to depict a sensation rather than a landscape.

The research about this painting wouldn't be complete without some mention of the idea of the sublime in Romantic era poetry and art. This aspect of Romantic era art is deeply connected to nature and how its beauty and treachery can force a perspective change in those who truly experience it. Equal parts agony and ecstasy. This painting surely depicts that feeling of the sublime and its connection to nature in the sensation of the treacherous cliffside the Wanderer stands upon. As someone with a fear of heights, I wonder if other people feel the way I do when I really look at this painting, because I really do feel a slight tingling of fear while looking at this painting when I put myself in as the Wanderer. Yet there is undoubtedly a feeling of wonder over the landscape below, one that I seem to feel even to my bones. I definitely understand now why this painting has become so symbolic of the Romantic era, as it seems to capture so many of the elements of it in a relatively simple painting.

Works Cited: Gaete, Miguel Angel. “From Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog to the ICloud: A Comparative Analysis between the Romantic Concept of the Sublime and Cyberspace.” Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics , vol. 43, no. 2, June 2020, p. 59. EBSCOhost , search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgac&AN=edsgac.A643530332&site=eds-live.

Prodger, Michael. “A Solitude Shared: How Caspar David Friedrich Searched the German Landscape for Reflections of His Soul.” New Statesman , vol. 149, no. 5530–5533, July 2020, p. 90. EBSCOhost , search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsglr&AN=edsglr.A632298532&site=eds-live.

Copyright:

Associated place(s), part of group:, featured in exhibit: , artist: .

- Caspar David Friedrich

Image Date:

- International

- Today’s Paper

- Premium Stories

- Express Shorts

- Health & Wellness

- Board Exam Results

Behind the Art: Why is Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich considered one of the masterpieces of the Romantic movement?

Behind the art: the iconic painting wanderer above the sea of fog was created in 1818 by german romantic artist caspar david friedrich. probably worth millions, it shows a man standing with his back to the viewer on a rocky cliff edge. why is this painting considered one of the masterpieces of the romantic movement.

The iconic painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog was created in 1818 by German romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich. Probably worth millions, it shows a man standing with his back to the viewer on a rocky cliff edge. He is looking out at a landscape that is covered in a thick sea of fog that cuts through other ridges, trees, and mountains and goes on forever. It has been regarded as one of the Romantic movement’s greatest works and one of its most illustrative masterpieces. It is unknown where the artwork came from after it was created; however, by 1939, it was in the gallery of Wilhelm August Luz in Berlin, Germany. In 1970, the Hamburger Kunsthalle in Hamburg, Germany, bought it, and it has been there ever since. But why is it considered a masterpiece and what the is story behind it?

What is the painting about?

What attracts viewers is the visual appeal of the painting . A man stands with his back to the viewer on a rocky precipice in the foreground. He is wearing a dark green overcoat and holding a walking stick in his right hand. The wanderer is looking out over a landscape that is covered in a thick sea of fog, his hair blowing in the wind. The painting is made up of various elements from the Elbe Sandstone Mountains in Saxony and Bohemia. Friedrich sketched them out in the field, but he rearranged them in the same way he usually does in the studio for the painting. As a result, it may not accurately depict the mountain ranges and their locations. Caspar David Friedrich often depicted his figures in this manner, which he referred to as a “compositional strategy/device.” The man stands with his back to the audience and the German word for “figure from the back” is Rückenfigur, which refers to this unique method.

Why did Friedrich paint the Wanderer above the sea of fog?

Friedrich’s paintings are dominated by the sublime power of nature. His personal history may also account for the ominous tension between beauty and terror in his depiction of nature, which was influenced by the landscapes of his native Germany. When he was young, he and his brother were skating on the frozen Baltic Sea when the ice cracked. Caspar fell, and his brother saved his life. It is said that this incident stayed with Friedrich for life and due to his depression, he attempted suicide in Dresden. He always wore a beard to cover the wound from his attempt to cut himself. Friedrich’s statement, “The painter should paint not only what he has in front of him, but also what he sees inside himself,” demonstrates the connection between inspiration and trauma.

It’s possible that Friedrich’s work, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, which he created the year he got married, is about his struggle to control his strong emotions for the sake of his young bride. Based on Caspar David Friedrich’s red hair colour, some art history sources suggest that the figure in this painting was the artist himself. Whereas, some historians claim that the man could be Colonel Friedrich Gotthard von Brincken and that this painting was made as a kind of “patriotic epitaph” for him after he died. This hints at Friedrich’s interest in politics in the early 19th century and suggests that he was a German Nationalist.

Romanticism and the legacy of the painting

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is considered a masterpiece of the Romantic movement which is a broad artistic and literary movement that emerged after the Age of Enlightenment. The Romantic movement was a European intellectual, artistic, literary, and musical movement that began toward the end of the 18th century. Romanticism was characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism, paganism, idealization of nature, distrust of science and industrialization. And this was what Caspar David Friedrich’s “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” captures. It shows a man confronting the vastness of nature and ultimately God. He is truly in the presence of greatness, and as we look at him as he looks out over the landscape and maybe even thinks about his life and the natural world. However, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog and Friedrich’s work, in general, were not immediately regarded as masterpieces, despite Friedrich’s respect in German and Russian circles. In the early 20th century, specifically in the 1970s, Friedrich’s reputation improved. Wanderer attracted a lot of attention: used as a source of inspiration for numerous works since and is not just well-known among art historians.

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog is more than 200 years old and still has an impact on viewers today, reminding us of age-old truths that appear to go beyond being human. In fact, critics claim that the subject looking upon a canvas of open possibility, ready to make a choice and find what awaits him, appeals to modern viewers. The Wanderer has appeared on the cover of numerous books, T-shirts, CDs, and coffee mugs. Friedrich’s paintings were even used as propaganda and tokens of appreciation for the German Adolf Hitler. Friedrich’s reputation as an artist was tarnished by this association, but the art world eventually restore it and make it one of the most talked about paintings in history.

What phase 1 voter turnout says about BJP’s chances in Subscriber Only

UPSC Essentials | Daily quiz: environment, geography, & more Sign In to read

Case before SC: Can govt redistribute privately owned property? Subscriber Only

Road ahead for Tesla: Why EV sector is struggling Subscriber Only

Engineering in local language sees uptick in students in UP, Subscriber Only

How Bengaluru’s lakes disappeared Subscriber Only

After wars, deaths, political turmoil, the era of Indira Gandhi Subscriber Only

Faced with coastal Karnataka ‘saffron wall’, Cong counts on welfare Subscriber Only

India’s trade with Israel & Iran, and impact of regional Subscriber Only

Dr Shushruth Gowda, a renowned doctor from Mysuru and KPCC general secretary, left the Congress and joined the BJP after being denied a ticket to contest the Lok Sabha elections. He is the son of late Dr H C Vishnumurthy, a socialist and founder chairman of a hospital in Mysuru. Gowda praised PM Modi's work and vowed to work for BJP candidate Yaduveer Krishnadatta Chamaraja Wadiyar's win.

More Lifestyle

Buzzing Now

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01 Study says it’s likely a warmer world made deadly Dubai downpours heavier

- 02 Richa Chadha calls her character in Heeramandi ‘female Devdas’, says she is scared to get ‘stereotyped as a drunkard woman’

- 03 SRH vs RCB Emotional Rollercoaster: A glimpse of how Pat Cummins bowls perfect T20 over and Patidar completes what Kohli started

- 04 BTS’ RM set to release solo album Right Place, Wrong Person

- 05 UAE announces $544.6 million to repair homes: How the flood-hit country is inching back to normalcy

- Elections 2024

- Political Pulse

- Entertainment

- Movie Review

- Newsletters

- Gold Rate Today

- Silver Rate Today

- Petrol Rate Today

- Diesel Rate Today

- Web Stories

Wanderer above the Sea Fog by Friedrich – Top 8 Facts

By: Author Trace Bradley

Posted on Published: February 28, 2022

If we have to pick one painting that defines the Romantic art movement, then this Romantic painting would be it.

Romantic artists in the first decade of the 19th century put a high emphasis on individuality and conveying personal emotion. This painting by one of the most famous German artists in history embodies this perfectly.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the most interesting facts about Wanderer above the Sea Fog by Caspar David Friedrich , a masterpiece by the artist for several reasons.

1. It was painted in the second decade of the 19th century

Wanderer above the Sea Fog is the most famous painting in the oeuvre of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), the leading German artist of his time. He was born a year earlier than J.M.W. Turner (1775-1841), the English painter who specialized in landscapes and maritime paintings.

The fascinating fact about this notion is that both artists elevated landscape painting into the new Romantic era around the same time. It took a bit longer for Friedrich to reach the same level of recognition as he only received his first major commissions around 1808, shortly settling in Dresden.

He completed this painting in 1818, the same year that he got married and at a time when his career was taking off.

2. It depicts a man standing on top of a mountain peak

The German name of the painting is “Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer” and it’s also known in English as “Wanderer above the Mist or “Mountaineer in a Misty Landscape.”

These titles pretty much explain what is depicted. We can see a mountaineer who is facing the viewer with his back while contemplating the scenery.

Mountain peaks are sticking out of the foggy landscape. Some of the peaks feature trees and a large mountain range can be seen emerging in the top left corner. The fog stretches out indefinitely and eventually merges with the horizon in the top right corner.

3. The painting embodies the spirit of the Romantic art movement

Wanderer above the Sea Fog is not just considered to be a masterpiece in its own right, but also the most famous painting representing the Romantic movement. That’s mainly because it embodies what the movement was about.

Romanticism was a reaction to the Industrial Revolution and the rationality of the Age of Enlightenment. It forced people to look inside themselves and see raw emotions.

In that sense, this painting is considered to be the epitome of self-reflection. You have to imagine what the depicted man thinks because we can’t see his face, only the fact that he is gazing upon this hazy landscape.

This forces you to somehow step into his shoes to feel what he might be feeling.

4. Some depicted mountains can be recognized

Friedrich moved to Dresden in the year 1798 after completing his studies at the prestigious Academy of Copenhagen. This is a major city in the eastern part of Germany, not too far from the modern-day border with the Czech Republic.

The painting depicts distinctive peaks in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, a mountain range that straddles the border of both countries. This range is situated in both the German state of Saxony and the Czech region of North Bohemia and not too far southeast of Dresden.

Friedrich used several mountain peaks and rearranged them to fit into the overall composition. These are:

- The Zirkelstein is in the top right corner.

- Either the Rosenberg or the Kaltenberg is in the top left corner.

- In the foreground, we can see a group of mountains called the Gamrig near the town of Rathen.

- The mountain on which the man stands is a group of mountains called the Kaiserkrone.

5. The painting had a positive influence on mountaineering

Mountaineering as we know it today was still in its infancy at the time that Friedrich completed this defining painting in the history of art.

We can see the man majestically standing on top of the mountain peak. This image wasn’t just important in the development of the Romantic art movement but also in the history of mountaineering.

It conveys a sense of power that comes along with conquering a mountain. It has been described as “an archetypical image of the mountain-climbing visionary.”

It was the start of associating climbing a mountain with something that should be admired, a notion that didn’t exist before.

6. Caspar David Friedrich made a famous comment about this painting

Caspar David Friedrich commented on his masterpiece by saying the following:

The artist should paint not only what he has in front of him but also what he sees inside himself.

This defines Romanticism and led the way for Romantic artists to paint works that aimed to move people rather than solely depict what is there.

This eventually fell out of favor with the rise of Realism artists halfway through the 19th century. Although Friedrich’s works were devalued because of this and he died in obscurity, his works inspired many artists of future generations, including Surrealists and Expressionists .

7. How big is Wanderer above the Sea Fog by Caspar David Friedrich?

Over 2 dozen of books have been published featuring Wanderer above the Sea Fog on their covers. These books were written in a wide variety of genres, ranging from Romantic novels to horror stories.

The popularity of the painting is associated with the sense of emotion that it conveys which can be pretty much everything. This doesn’t mean, however, it was painted at a monumental scale.

The oil on canvas painting has dimensions of 94.8 × 74.8 centimeters (37.3 × 29.4 inches) .

8. Where is the painting located today?

The painting is one of the main attractions of the Hamburger Kunsthalle , a large art museum in the German city of Hamburg in the northern part of the country.

The museum in Hamburg consists of 3 interconnected buildings in the historic heart of the city that were built at different times in history.

These are the main building (1869), the Kuppelsaal (1921), and the Galerie der Gegenwart (1997).

Friedrich’s work can be found in a gallery dedicated to artists of the 19th century and also houses another one of his famous works called “The Sea of Ice” (1824).

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich

What is the meaning behind the painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich?

- Rumination and romance

- Exultation in one man’s insignificance

- A mysterious mist sets a sublime scene

Click here for the podcast version of this post.

A man’s back becomes much more in Wanderer above the Sea of Fog . Like many of Caspar David Friedrich’s works, it combines landscape and portrait. But this one’s his masterpiece. In fact, many art historians consider it the defining work of the Romantic art movement. I agree. This painting distinguishes itself among Friedrich’s other landscape portraits in many ways.

Interplay between figure and setting reveal the most powerful part of this piece. In many Friedrich paintings the figure plays a minimal role. He tended to emphasize landscapes. But in Wanderer above the Sea of Fog we discover a sense of sublime contemplation. There’s more than a mere landscape or figure here. Together, the foggy crag and stalwart figure make magic of meditation.

Friedrich keeps the canvas simple. We see only bluffs, fog, and a man with a walking stick at the forefront. These elements feel close and clear. Friedrich blends foggy wisps into the nebulous background… both earth and sky. We know the mountains and forest loom beyond. But also that they’re not the point. That’s because of our wanderer. He wears traditional clothes and surveys the scene with a thoughtful posture. We see in his stance that the walking stick isn’t a necessity now. He’s not leaning on it. Rather, it’s a prop that represents this man’s journey.

Romanticism

Romantic art sprouted wings in Europe in the early 1800s. This movement revolved around intense emotion. Prevalent examples included awe and fear. Romantics often portrayed these feelings regarding nature’s beauty and the sublime. In today’s world, romance has an amorous meaning. But that wasn’t the case in 1800s Romanticism. In fact, some of the most iconic Romantic artworks focus on a single figure. Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog sets a perfect example.

Rückenfigur