ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

The underground railroad.

During the era of slavery, the Underground Railroad was a network of routes, places, and people that helped enslaved people in the American South escape to the North.

Social Studies, U.S. History

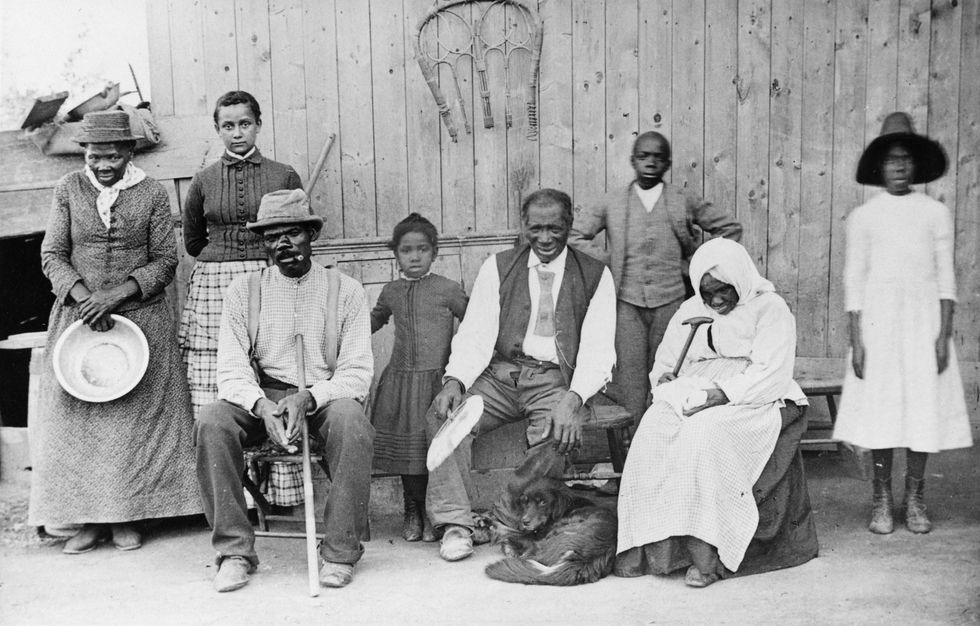

Home of Levi Coffin

Historic image of the home of American Quaker and abolitionist Levi Coffin located in Cincinnati, Ohio, with a group of African Americans out front.

Photography by Cincinnati Museum Center

During the era of slavery , the Underground Railroad was a network of routes, places, and people that helped enslaved people in the American South escape to the North. The name “ Underground Railroad ” was used metaphorically, not literally. It was not an actual railroad, but it served the same purpose—it transported people long distances. It also did not run underground, but through homes, barns, churches, and businesses. The people who worked for the Underground Railroad had a passion for justice and drive to end the practice of slavery —a drive so strong that they risked their lives and jeopardized their own freedom to help enslaved people escape from bondage and keep them safe along the route.

According to some estimates, between 1810 and 1850, the Underground Railroad helped to guide one hundred thousand enslaved people to freedom. As the network grew, the railroad metaphor stuck. “Conductors” guided runaway enslaved people from place to place along the routes. The places that sheltered the runaways were referred to as “stations,” and the people who hid the enslaved people were called “station masters.” The fugitives traveling along the routes were called “passengers,” and those who had arrived at the safe houses were called “cargo.”

Contemporary scholarship has shown that most of those who participated in the Underground Railroad largely worked alone, rather than as part of an organized group. There were people from many occupations and income levels, including former enslaved persons . According to historical accounts of the Railroad, conductors often posed as enslaved people and snuck the runaways out of plantations. Due to the danger associated with capture, they conducted much of their activity at night. The conductors and passengers traveled from safe-house to safe-house, often with 16-19 kilometers (10–20 miles) between each stop. Lanterns in the windows welcomed them and promised safety. Patrols seeking to catch enslaved people were frequently hot on their heels.

These images of the Underground Railroad stuck in the minds of the nation, and they captured the hearts of writers, who told suspenseful stories of dark, dangerous passages and dramatic enslaved person escapes . However, historians who study the Railroad struggle to separate truth from myth . A number of prominent historians who have devoted their life’s work to uncover the truths of the Underground Railroad claim that much of the activity was not in fact hidden, but rather, conducted openly and in broad daylight. Eric Foner is one of these historians. He dug deep into the history of the Railroad and found that though a large network did exist that kept its activities secret, the network became so powerful that it extended the limits of its myth . Even so, the Underground Railroad was at the heart of the abolitionist movement. The Railroad heightened divisions between the North and South, which set the stage for the Civil War .

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Untold Stories of American History

Explore the lives of little-known changemakers who left their mark on the country

History | July/August 2022

South to the Promised Land

Before the Civil War, numerous enslaved people made the treacherous journey to Mexico in a bold quest for freedom that historians are now unearthing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ce/60/ce6064ef-205d-4e53-8d41-194398e24e14/social.jpg)

A trail wends through the notoriously inhospitable brush country along the U.S.-Mexico border known as the Nueces Strip.

By Richard Grant

Photographs by Scott Dalton

Diana Cardenas, a high school English teacher from Pharr, Texas, stands in her small family cemetery between the Rio Grande and the new border wall. Stylishly dressed and coiffed, wilting slightly in the heat and humidity, she holds up a photograph of her grandmother. “Her name was Adela Jackson, and we were close,” she says. “She loved to come here, and tell me stories about our family history, and all the runaway slaves we helped and took across the river into Mexico.”

Until recently, the southbound Underground Railroad, as some scholars call it, has been largely overlooked, mainly because it left so few traces in surviving records. No one who escaped slavery by going to Mexico wrote a firsthand account of the experience, as Frederick Douglass and others did about escaping north. Nor were they interviewed by researchers, or recruited by antislavery organizations. And though the journeys of enslaved people to Mexico are of the utmost importance, the scale of the southern migration was more modest, numbering between 3,000 and 10,000 people, compared with an estimated 30,000 to 100,000 who fled north of the Mason-Dixon line.

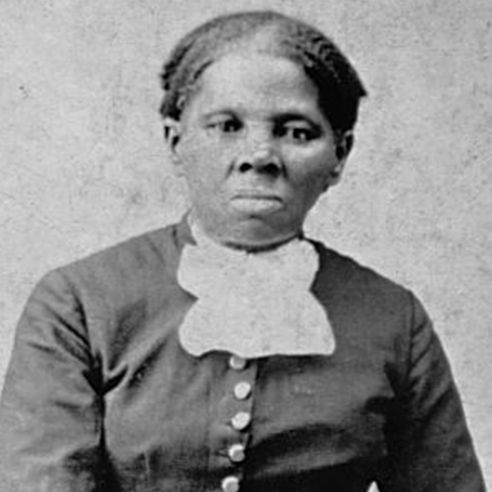

But in recent years scholars have begun to uncover a wealth of information about the southbound freedom-seekers. For example, they’ve learned that while there was no organized network of assistance, no celebrated “conductors” like Harriet Tubman guiding them to the next safe haven, slaves escaping to Mexico did sometimes receive help along the way.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/4a/794a082b-a625-4e4a-a9cd-9bf63e615665/julaug2022_c10_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Diana Cardenas’ great-great-great-grandfather, who died in obscurity, was among the staunchest allies of slaves escaping south. “He was a white man from Alabama named Nathaniel Jackson,” says Cardenas. “He married a slave that he freed, Matilda Hicks, and they came out here in covered wagons in 1857. She already had three children by another man, and she had seven more with Nathaniel.”

Cardenas produces a faded, blurry, copied photograph, a family heirloom, showing a woman she believes is Matilda Hicks, her great-great-great-grandmother, tall and thin and wearing a white dress.

“Nathaniel bought 5,535 acres of land right here by the river and established the Jackson Ranch,” says Cardenas. “There were Black, white and mixed-race people all living together, raising cattle in a place that was very remote, where they could be left alone. The runaways knew they could get help here—food, clothing and work if they wanted it. Nathaniel was a nice, generous, courageous man, a humanitarian. He would cross them into Mexico in boats.”

The history of southbound runaways, preserved in scattered fragments, presents scholars with enormous challenges of research and interpretation. Perhaps no one has done more to advance our understanding than a historian named Alice Baumgartner. In 2012, as a Rhodes scholar studying violence on the U.S.-Mexico border in the early and mid-19th century, she was hunting through state and municipal archives in northern Mexico. She found plenty of documents about cattle rustling and Lipan Apache raids, but she also came across records of a completely unexpected kind of violence—between American slave catchers crossing the Rio Grande and Mexicans who fought against them.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/47/42471836-7102-4834-ab1c-12bbe11650cc/julaug2022_c09_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

“It really caught my attention, because I didn’t know that enslaved people were escaping into Mexico, and I never would have suspected that Mexican citizens and officials were protecting them,” says Baumgartner, now an assistant professor of history at the University of Southern California .

She was particularly struck by the story of Manuel Luis del Fierro of Reynosa, in the state of Tamaulipas, who was startled awake by screaming on the night of August 20, 1850. He threw off the covers, grabbed his rifle and confronted two men in his living room. One was waving a pistol at his wife’s maid, a young Black woman named Mathilde Hennes, who had escaped slavery in Louisiana, made the long, dangerous journey to Mexico, and become a valued member of Del Fierro’s household.

Pointing his rifle at the kidnappers, Del Fierro ordered them to surrender. One got away, but the other—William Cheney of Cheneyville, Louisiana, who claimed Hennes as his property under U.S. law—was arrested by the Reynosa police, imprisoned for nearly a month, and sent home empty-handed.

The incident was not unusual, Baumgartner discovered. She read the correspondence of four councilmen from the Mexican border town of Guerrero, who pursued, shot and killed a slaveholder who had kidnapped a runaway. In 1851, the residents of another village in the state of Coahuila took up arms to stop a slave catcher named Warren Adams from abducting a Black family. Months later, the Mexican Army posted a sizable force and two artillery pieces on the Rio Grande to prevent a group of 200 Texans from crossing the border to seize runaway slaves.

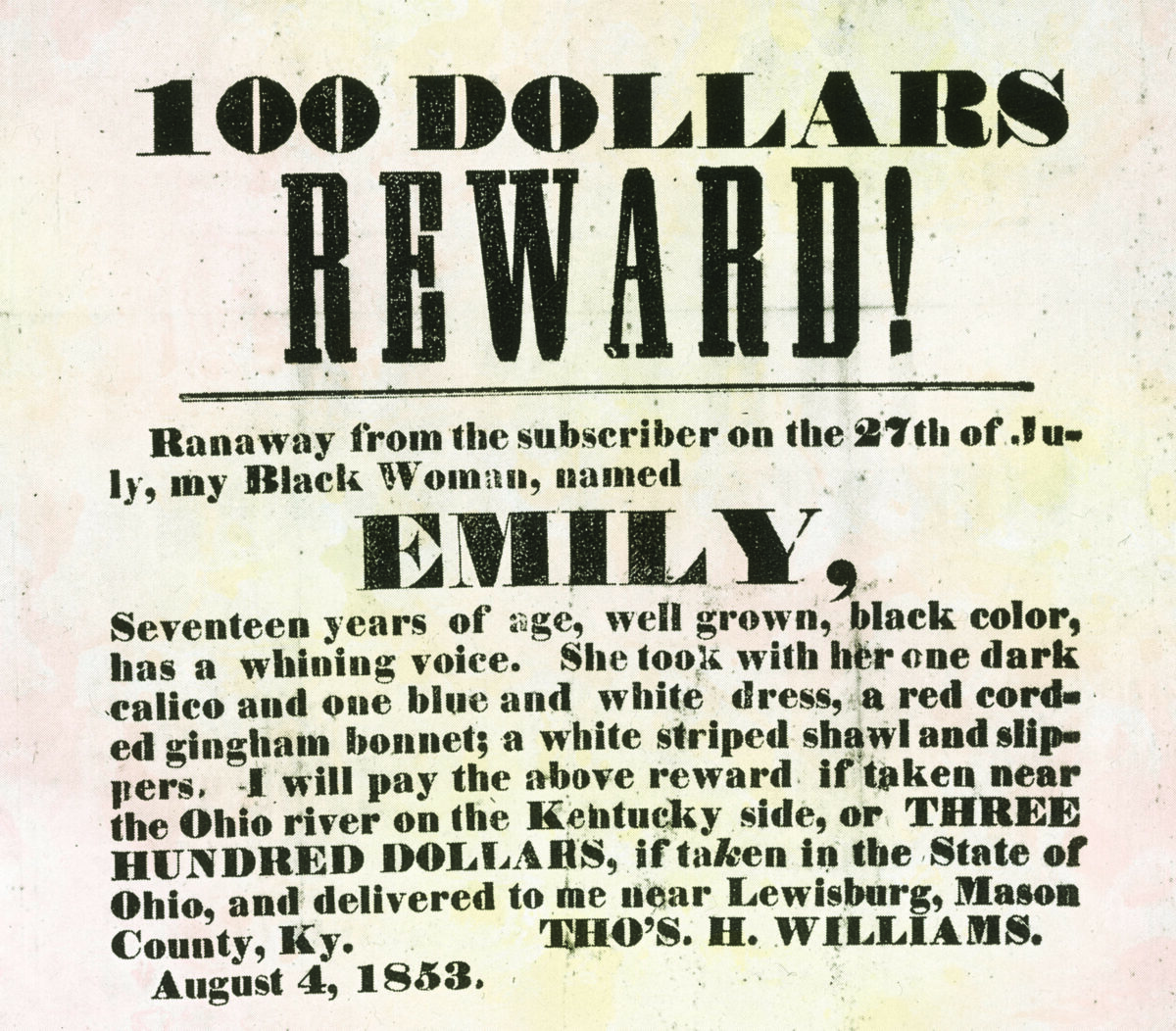

Baumgartner kept uncovering information that surprised and fascinated her. After independence from Spain, in 1821, “Mexico passed these really radical antislavery laws, and Mexicans at all levels of society were serious about enforcing them,” she told me recently. “This was well known by enslaved people on the U.S. side of the border.” Indeed, more than three-quarters of the fugitive slaves caught in Texas between 1837 and 1861, she learned from a database of runaway slave notices, were heading to Mexico.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f8/d8/f8d81b71-f828-46c2-b9e5-bbafba1c60e7/julaug2022_c13_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Baumgartner went on to search 28 archives in three countries—Mexico, the United States and Britain—and wrote the first full-length book about the subject, South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War . The book, published in 2020, was lauded for its groundbreaking historical insights and panoramic sweep. “Masterfully researched,” wrote a reviewer for the New York Times . Publishers Weekly called it “an eye-opening and immersive account.” “Black Perspectives,” the digital publication of the African American Intellectual History Society, argued that it made “a convincing case that Mexico shaped the freedom dreams of enslaved people in states like Texas and Louisiana.”

At the heart of Baumgartner’s study were a few simple questions: “Why were enslaved people escaping to Mexico?” she says. “What did they find there? Why were Mexicans helping them?”

Felix Haywood of San Antonio, a former slave interviewed in 1937 for the Federal Writers’ Project, didn't himself try to escape south, but he heard stories about those who did, and he visited Mexico after the Civil War before returning to Texas. “There wasn’t no reason to run up North,” he told the interviewer. “All we had to do was walk, but walk South, and we’d be free as soon as we crossed the Rio Grande. In Mexico you could be free. They didn’t care what color you was—black, white, yellow or blue.”

The earliest examples of slaves escaping south are from the late 17th century. In the Carolinas, enslaved men and women ran away from the rice plantations to Spanish Florida, where they were able to arm themselves against their former enslavers. In 1693 King Charles II of Spain decreed that all fugitive slaves would be free in Florida. In 1733 a caveat was added: To gain their freedom, fugitives had to convert to Catholicism and declare loyalty to the Spanish crown. In 1750 the same promise was extended to the entire Viceroyalty of New Spain, which included all of present-day Mexico and nearly all of the American West, plus Florida.

After the Louisiana Purchase, in 1803, the de facto border between the United States and New Spain was the Sabine River, in present-day East Texas. (This border was formalized in 1819.) It’s impossible to say how many enslaved people made it across the Sabine, but we know that slaveholders in Louisiana complained about escapes to New Spain. Thomas Mareite, a French historian at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany, has found evidence that 30 slaves from plantations on the Cane River near Natchitoches left for New Spain in October 1804. Nine crossed the Sabine River, and a string of similar escape attempts followed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/54/6d/546de218-7131-483a-9453-81be6045b017/julaug2022_c02_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

In January 1808 a Black man recorded as “Rechar,” presumably Richard, arrived at Trinidad de Salcedo, a small Spanish outpost near present-day Madisonville, Texas. He told his story to the authorities. His family had been split up by enslavers and scattered all over southern Louisiana. Having made his own escape from a plantation in Opelousas, he managed to find and rescue his wife and three of their seven children. He tried, and failed, to rescue the other four, then led his reduced family across more than 100 miles of swampy wilderness and crossed the Sabine River into freedom. (Their fate in Spanish territory is unknown.)

Even though slavery existed in New Spain, American runaways were usually granted asylum by the Spanish authorities, because the American form of slavery was regarded as far more brutal and dehumanizing. In New Spain, for example, slaves were subjects of the Spanish crown, not property, and it was illegal to separate husbands and wives or to impose excessive punishments. Rechar declared that “the harshness of American laws” as well as keeping his family together were the reasons for his escape.

In 1821, after Mexico won its independence, it opened the northern frontier state of Tejas (as Texas was then called) to Anglo American settlers. Many of those settlers brought Black slaves and established American-style cotton plantations in present-day East Texas. This set up a conflict with the Mexican government, which banned the importation of enslaved people in 1824, on the principle of liberty for all.

The Anglo colonists ignored the law or imposed lifetime contracts of indentured servitude on their Black workers. The state of Coahuila y Tejas responded by limiting indenture contracts to ten years, and guaranteeing liberty to the children of slaves, in a so-called “free womb” law. In 1835, the Anglo settlers, bristling at these and other laws they regarded as oppressive, rose up in revolt. “It’s controversial, especially in Texas, but the historical profession is coming to a consensus that slavery was an important part of the Texas Revolution,” says Baumgartner.

In 1836, Texas won independence from Mexico and, now an autonomous republic, enshrined slavery in its constitution. Mexico fully abolished slavery the following year. In 1845, Texas joined the United States as a slave state. Then came the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. Defeat forced Mexico to relinquish all or parts of the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Wyoming.

“This was the first time in its history that the U.S. acquired territory where slavery was [previously] abolished by law,” says Baumgartner.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/65/cd/65cdc2e0-c96b-4528-8a40-b878a423e6a5/julaug2022_c99_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

At the same time, Southern politicians attempted to expand slavery by annexing Cuba, where it was firmly entrenched, and by working to overturn the Missouri Compromise, which had prohibited slavery in much of the territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. When these and other efforts failed, secession and Civil War followed.

The idea that Mexico’s antislavery laws not only encouraged African American slaves to cross the southern border but also ignited the Texas Revolution and inflamed the conflict between North and South that led to the American Civil War is the essence of Baumgartner’s groundbreaking argument. “It reorders the way we should think and teach about the slavery expansion crisis,” David Blight, the Yale historian and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of 2018’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom , says. “Indeed, it reorders how to think about the huge question of the coming of the American Civil War.”

In 1849, Mexico’s congress decreed that foreign slaves would become free “by the act of stepping on the national territory.” This soon became common knowledge among enslaved people in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and what would later become Oklahoma. They envisioned what historian Mekala Audain calls a “Mexican Canaan” across the Rio Grande—a promised land where they could be free. They made the arduous journey through Texas. They stowed away on boats leaving from Galveston and New Orleans for Tampico and Veracruz. In the 1850s a dozen slaves were reaching Matamoros, Mexico, every month. Two-hundred-seventy arrived in Laredo, in Tamaulipas (now called Nuevo Laredo, just across the border from Laredo, Texas) in a single year. American diplomats kept pressuring their Mexican counterparts to sign extradition treaties, which would return runaway slaves to their owners, but Mexico flatly refused—in 1850, 1851, 1853 and 1857.

Audain, an associate professor at the College of New Jersey, is currently finishing a book about the experiences of enslaved African Americans in the Texas-Mexico borderlands. “One distinct aspect of escapes in Texas was navigating the terrain,” she says. “Depending on where they began their escapes, there could be limited shade and water, especially as they traveled south of San Antonio. A lack of trees also limited their abilities to camouflage themselves.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9c/64/9c644420-21a8-458f-b830-36262994952d/julaug2022_c05_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

There were several different routes to Mexico. Slaves escaping from Louisiana tended to go via Nacogdoches to Houston and cross the border to Matamoros. Another route went from the vicinity of Austin to San Antonio and then to Laredo in Tamaulipas or Piedras Negras in Coahuila. Using established roads, or keeping them in sight, made it easier to navigate, but increased the likelihood of confrontation and capture.

Most northbound runaways were on foot and unarmed, but many southbound freedom-seekers, especially from Texas, rode horses and carried guns. “It was a reflection of the culture and the most effective strategy,” says Audain. “They could travel faster, defend themselves and hunt for food.” Escaping on horseback probably also helped to neutralize the much-feared bloodhounds and other slave-hunting dogs; the dogs had no clear human scent to follow and likely couldn’t keep up with horses over long distances.

Kyle Ainsworth, a historian and special collections librarian who runs the Texas Runaway Slave Project at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, has calculated from runaway slave notices that 91 percent of Texas escapees were male, with an average age of 28. “Many women were responsible for raising their children,” says Ainsworth. “It was very difficult for enslaved people to run away with young children, although there are definitely a few examples where they tried.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/9f/8d9f63ff-f7df-443d-a6b4-51b0c29bc426/julaug2022_c11_undergroundrailroad_copy.jpg)

Baumgartner has noted the ingenuity many escaping slaves showed. “They forged passes to give the impression they were traveling with the permission of their masters. They disguised themselves as white men, fashioning wigs from horsehair and pitch. They stole horses, firearms, skiffs, dirk knives, fur hats, and in one instance, 12 gold watches and a diamond breast pin.”

Some fugitives were helped by other slaves, free Black people, Mexicans, Germans and other sympathetic white people, but these allies operated independently of one another and risked being tarred, feathered, hanged or shot for helping slaves escape. One former slave who made it to Chihuahua, Mexico, and was later captured, said mail carriers helped him escape, but this appears to be an isolated example.

For the great majority, the journey south was an improvisation, a wayfinding through an unknown and hostile geography. They lived by their wits on a constant knife-edge of danger; for those on foot, the journey could take months. Often pursued by their enslavers, or hunted by slave patrols, with a bounty on their heads that any citizen might attempt to collect, they had to find food and water and contend with the Texas climate—well over 100 degrees in summer and subject to sudden, freezing “blue norther” storms in winter. Native Americans were another threat.

The most dangerous part of the journey was the Nueces Strip—a 100- to 150-mile expanse of remote, thorny, rattlesnake-infested brush country between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. It contained few roads or settlements, which made it hard to navigate and find food, and very little water. There was no slavery this far south in Texas, because the risk of slaves escaping to Mexico was too great. Black people were highly conspicuous and immediately suspected of being fugitives. “The Nueces Strip was also where runaway slaves were most likely to encounter slave catchers, military patrols, Texas Rangers and Indians—all of whom would capture them or worse,” says Ainsworth.

If they reached the Rio Grande near present-day Pharr, Texas, runaways could expect help and kindness from Nathaniel Jackson and his neighbors, but the river ran for more than 1,000 miles along the international border, and most runaways reached it elsewhere. For Audain, the most affecting stories are those that end with drownings in the Rio Grande. “I think of all the effort they put into planning their escapes, walking hundreds of miles across Texas, and managing to avoid kidnappers and patrols,” she says. “They somehow survived these challenges, only for their journeys to end not with freedom, but with death.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0f/00/0f0030cf-d781-4d41-a1c6-e33d10e6172d/julaug2022_c12_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Mareite, the French historian, uses the phrase “conditional freedom” to describe what runaway slaves found in Mexico. Alice Baumgartner compares it to the abridged freedom that runaways found north of the Mason-Dixon line, where the U.S. Constitution, through the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850, provided for their capture and return to slavery. In Mexico, federal law guaranteed freedom to runaways, but they were always at risk from North American slave hunters who crossed the border illegally and broke Mexican antislavery laws.

Most runaways arrived in Mexico with little or no Spanish. A few were able to establish themselves as merchants, carpenters and bricklayers in Matamoros and other cities. For the great majority, however, there were two options. They could find work as servants or day laborers on ranches and haciendas. Or they could risk their lives once again by joining military colonies.

These were fortified outposts established by the Mexican government to defend its northeast borderlands from devastating raids for livestock, captives and plunder by Comanches and Lipan Apaches. In return for such military service, according to a law passed by Mexico’s congress in 1846, foreigners, including runaway slaves, would receive land and full citizenship. Historians know little about the experiences of African Americans in these military colonies, with one significant exception.

At a colony in Coahuila were Black Seminoles, descended from free Black people and slaves who had run away from Georgia and the Carolinas and allied themselves with the Seminole Indians in Florida. They had fought with the tribe in the three Seminole Wars against the U.S. Army. When they were finally defeated, the Seminoles and Black Seminoles were forced onto the Creek reservation in Indian Territory, in present-day Oklahoma, with most arriving by 1842. The Creeks denied the newcomers land and started capturing Black Seminoles and selling them into slavery in Arkansas and Louisiana. By 1849, says Baumgartner, “the Seminoles and their Black allies had had enough.”

The Seminole leader Wild Cat, with the assistance of John Horse, leader of the Black Seminoles, led more than 300 men, women and children, including 84 Black Seminoles, from Indian Territory south to Mexico. In northern Coahuila, the Mexican government granted them a 70,000-acre military colony with work animals, agricultural equipment and financial subsidies. Within months of arriving, Wild Cat went back to Indian Territory and returned with about 40 more Seminole families and most of the remaining Black Seminoles.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f3/69/f369358b-5d31-41ee-a756-6aac7ef74a9a/julaug2022_c14_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Runaway slaves started arriving before the colonists had finished clearing fields and building their wood-frame houses. One man named David Thomas had escaped with his daughter and three grandchildren. In 1850, a group of 17 arrived, asking to join the Black Seminoles. By 1851, there were 356 Black people living at the colony, and three-quarters of them were runaway slaves. At a moment’s notice, all the adult males had to be ready to fight against the Comanches or Apaches, arguably the most formidable Native American warriors on the continent.

In her book, Baumgartner describes an early morning scene at the outset of a military campaign: “bright-kerchiefed heads appeared in the low doorways of the houses; women unhobbled the horses, slipping bits into their mouths. Then the men emerged, a powder horn and a bullet pouch slung across a shoulder, a machete or a horse pistol in hand.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fa/19/fa198001-790c-424e-a12a-c5a5e4eb7476/julaug2022_c04_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

The Black Seminoles, known as Mascogos in Mexico, had a well-earned reputation as superb trackers and fighters. On foot or on horseback, according to the historian Kenneth Porter, who gathered their oral histories in the 1940s, the stronger men would use muskets as clubs. “They beat down buffalo-hide shields, splintered lance shafts, and rammed the iron-shod stocks into their enemies’ astonished faces.” Others used machetes to hack off spear and lance points, and then decapitate their foes. In a battle known in the oral history as “the big fight,” 30 or 40 Black Seminoles defeated a much larger force of Comanches and Apaches, and much of the fighting was hand-to-hand combat.

Descendants of the Black Seminoles and the runaways who joined them are still living in the town of El Nacimiento de los Negros (literally The Birth of the Blacks) in northeast Coahuila. Every year on June 19 they stage a celebration with dancing and barbecues. The women dress up in long, polka-dot pioneer dresses. The children sing songs in an old African American dialect of English that can be found in Negro spirituals. Only recently, according to Baumgartner, did the villagers learn their tradition is connected to Juneteenth, which celebrates the end of slavery in the United States. “In Nacimiento, it’s called Día de los Negros or Day of the Blacks,” she says.

In Porter’s unpublished oral histories, which Baumgartner was thrilled to find in an archive at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, people in El Nacimiento describe cultural traditions that date back to slavery. “Even though they’re in a Catholic country, with a priest posted in their community to make sure they’re good Catholics, they’re still celebrating the marriage ceremony by jumping over the broomstick,” says Baumgartner.

Thanks to Porter, Baumgartner was able to conjure the lives of the Black Seminoles and the runaways in their colony. But she found no detailed source material about other African Americans in Mexico, and has failed to find any other descendants. “Many of them took Spanish names and married into Mexican families,” she says. “And the Mexican government stopped keeping track of anyone’s race in 1821 with official documentation.”

With enslavers, Texas Rangers, bounty hunters and slave catchers all crossing the border to kidnap runaways in Mexico, the last thing Black refugees wanted to do was advertise their presence. They lived as discreetly as possible. “They evaded their enslavers for the same reason they’re evading historians,” says Baumgartner. “It’s hard to get too mad about that.”

A mockingbird calls from a mesquite tree in the graveyard as the sun sets over the Rio Grande. The manicured hand of Diana Cardenas goes back into her folder of photographs and produces a portrait of a handsome, broad-faced Black man in work clothes and a well-worn hat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2e/2a/2e2ac4d4-e201-4b81-a657-c8e8b17c3d15/julaug2022_c03_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

Cardenas stares at the photograph, wishing she knew more about this man, who escaped bondage by fleeing south through Texas yet did not take the final step of crossing the river. “I don’t have his name, but my grandmother told me this man stayed here and married into one of the local Hispanic families,” she says. “He took a Hispanic last name and his children grew up speaking Spanish.”

She doesn’t know how many runaway slaves passed through the Jackson Ranch on their way to Mexico, but from her grandmother’s stories she estimates several dozen at least and perhaps a hundred. “Dozens more stayed and married into local families,” she says. “Not everyone wants to admit it, but there’s a lot of African blood around here, and most of it came from the runaway slaves who stayed.”

A few miles downriver, in another small family cemetery, two women tell the story of a white man named John Webber. “He came to Mexican Texas as a single man and settled near Austin in Webber’s Prairie, which later became Webberville,” says Roseann Bacha-Garza, a historian. “He fell in love with his neighbor’s slave, Silvia Hector, and had children with her. He emancipated her in 1834, married her, and purchased the freedom of their children.”

After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 passed, Webber moved his family to the lower Rio Grande Valley, and bought 8,856 acres of land in 1853. “Like the Jackson Ranch, it became a stopping place for runaway slaves going to Mexico,” says Sofia Bravo, a direct descendant of Webber and Hector’s. Bacha-Garza adds, “John and Silvia built a ferry landing and licensed a ferry that went across to the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. It was useful for his business—he was a trader—and also for ferrying runaways.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/35/36355da3-6944-459b-9f41-296a1ff41110/julaug2022_c07_undergroundrailroad.jpg)

“I’m very proud of my great-great-grandfather,” says Bravo. “It took guts to marry a Black woman and bring her here. He provided for her and her children, and he didn’t care what race you are.” Glancing around the muddy cemetery at the graves of her ancestors, who include Caucasian Spaniards, African Americans and Indigenous Mexicans, she adds, “I’m the same way. We all fit in the same-size hole when we’re dead.”

*Editor's Note, 7/14/2022: An earlier version of this story identified a photograph held by Diana Cardenas as Matilda Hicks, her great-great-great-grandmother. Other family members believe the photo does not show Hicks. The text and caption have been updated.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Richard Grant | | READ MORE

Richard Grant is an author and journalist based in Tucson, Arizona. His most recent book is The Deepest South of All: True Stories from Natchez, Mississippi .

Scott Dalton | READ MORE

Photographer Scott Dalton, a Texas native, works primarily along the U.S.-Mexico border.

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Notes from the Underground Railroad: How Slaves Found Freedom

Passengers on this “railroad” never forgot their life-or-death journey from bondage.

Arnold Gragston struggled against the current of the Ohio River and his own terror the first night he helped a slave escape to freedom. With a frightened young girl as his passenger, he rowed his boat toward a lighted house on the north side of the river. Gragston, a slave himself in Kentucky, understood all too well the risks he was running. “I didn’t have no idea of ever gettin’ mixed up in any sort of business like that until one special night,” he remembered years later. “I hadn’t even thought about rowing across the river myself.”

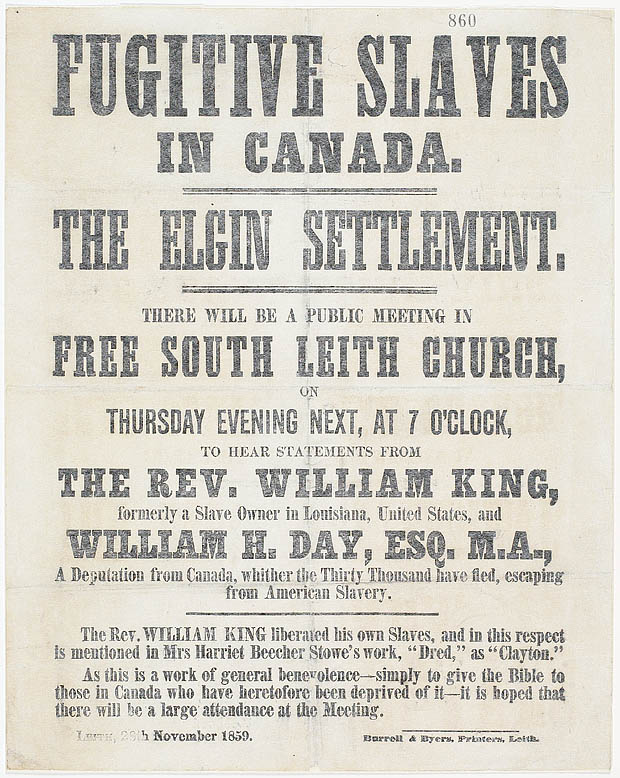

Slaves had been making their way north to freedom since the late 18th century. But as the division between slave and free states hardened in the first half of the 19th century, abolitionists and their sympathizers developed a more methodical approach to assisting runaways. By the early 1840s, this network of safe houses, escape routes and “conductors” became known as the “Underground Railroad.” Consequently, a cottage industry of bounty hunters chasing escaped slaves sprang to life as lines of the railroad operated across the North—from the big cities of the East to the little farming towns of the Midwest. Above all else, the system depended on the courage and resourcefulness of African Americans who knew better than anyone the pain of slavery and the dangers involved in trying to escape.

In a 1937 interview with the Federal Writers’ Project, Gragston recalled that his introduction to the Underground Railroad had occurred only a day before his hazardous trek, when he was visiting a nearby house. The elderly woman who lived there approached him with an extraordinary request: “She had a real pretty girl there who wanted to go across the river, and would I take her?”

The dangers, as Gragston well knew, were great. His master, a local Know-Nothing politician named Jack Tabb, alternated between benevolence and brutality in the treatment of his slaves. Gragston remembered that Tabb designated one slave to teach others how to read, write and do basic math. “But sometimes when he would send for us and [if] we would be a long time comin’, he would ask us where we had been. If we told him we had been learnin’ to read, he would near beat the daylights out of us—after getting somebody to teach us.”

Gragston suspected such arbitrary displays of cruelty were meant to impress his master’s white neighbors and considered Tabb “a pretty good man. He used to beat us, sure; but not nearly so much as others did, some of his own kin people, even.”

Tabb seemed especially fond of Gragston and “let me go all about,” but Gragston realized what would happen if he were caught helping a slave escape to freedom—Tabb would probably shoot him or whip him with a rawhide strap. “But then I saw the girl, and she was such a pretty little thing, brown-skinned and kinda rosy, and lookin’ as scared as I was feelin’,” he said. Her plaintive countenance won out, and “it wasn’t long before I was listenin’ to the old woman tell me when to take her and where to leave her on the other side.”

While agreeing to make the perilous journey, Gragston insisted on delaying until the next night. The following day, images of what Tabb might do wrestled in Gragston’s mind with the memory of the sad-looking fugitive. But when the time came, Gragston resolved to proceed. “Me and Mr. Tabb lost, and as soon as [dusk] settled that night, I was at the old lady’s house.

“I don’t know how I ever rowed the boat across the river,” Gragston remembered. “The current was strong and I was trembling. I couldn’t see a thing there in the dark, but I felt that girl’s eyes.”

Gragston was certain the effort would end badly. He assumed his destination would be like his home in Kentucky, filled “with slaves and masters, overseers and rawhides.” Even so, he continued to row toward the “tall light” the old woman had told him to look for. “I don’t know whether it seemed like a long time or a short time,” he recalled. “I know it was a long time, rowing there in the cold and worryin’.” When he reached the other side, two men suddenly appeared and grabbed Gragston’s passenger—and his sense of dread escalated into horror. “I started tremblin’ all over again, and prayin’,” he said. “Then one of the men took my arm and I just felt down inside of me that the Lord had got ready for me.” To Gragston’s astonishment and relief, however, the man simply asked Gragston if he was hungry. “If he hadn’t been holding me, I think I would have fell backward into the river.”

Gragston had arrived at the Underground Railroad station in Brown County, Ohio, operated by abolitionist John Rankin. A Presbyterian minister, Rankin published an anti-slavery tract in 1826 and later founded the American Anti-Slavery Society. Rankin and his neighbors in Ripley provided shelter and safety for slaves fleeing bondage. Over the years, they helped thousands of slaves find their way to freedom—and Gragston, by his own estimate, assisted “way more than a hundred” and possibly as many as 300.

He eventually made three to four river crossings a month, sometimes “with two or three people, sometimes a whole boatload.” Gragston remembered the journeys more vividly than the men and women he took to freedom. “What did my passengers look like? I can’t tell you any more about it than you can, and you weren’t there,” he told his interviewer. “After that first girl—no, I never did see her again—I never saw my passengers.” Gragston said he would meet runaways in the moonless night or in a darkened house. “The only way I knew who they were was to ask them, ‘what you say?’ And they would answer, ‘ Menare .’” Gragston believed the word came from the Bible but was unsure of its origin or meaning. Nevertheless, it served its purpose. “I only know that it was the password I used, and all of them that I took over told it to me before I took them.”

The dangers increased as Gragston continued his work. After returning to Kentucky one night from a river crossing with 12 fugitives, he realized he had been discovered. The time had come for Gragston and his wife to make the journey themsleves. “It looked like we had to go almost to China to get across that river,” he remembered. “But finally, I pulled up by the lighthouse, and went on to my freedom—just a few months before all of the slaves got theirs.”

The work of the Underground Railroad involved a network of white abolitionists, dedicated slaves like Gragston and free African Americans such as William Still of Philadelphia. The youngest of 18 children, Still was born in 1821, moved to Philadelphia in the mid-1840s and went to work for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society as a mail clerk and janitor. He rose to prominence in the city’s burgeoning abolitionist movement and served as chairman of the General Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia. Still was closely involved in the planning, coordinating and communicating required to keep the Underground Railroad active in the mid-Atlantic region. He became one of the most prominent African Americans involved in the long campaign to shelter and protect runaways.

In The Underground Rail Road , a remarkable book published in 1872, Still recounted the stories of escaped slaves whose experiences were characterized by courage, resourcefulness, pain at forced partings from family members and, above all, a desperate longing for freedom. For Still, aiding runaway slaves—and helping to keep families intact—was a deeply personal calling. Decades earlier, his parents had escaped slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. William’s father, Levin, managed to buy his freedom after declaring as a young man that “I will die before I submit to the yoke.”

William’s mother, Sydney, remained in bondage, but she fled with her four children to Greenwich, N.J., only to be seized by slave-hunters. Sydney and her family were returned to Maryland, but she escaped a second time to New Jersey. She changed her name to Charity to avoid detection and rejoined her husband, but their reunion was tarnished by the knowledge that she was forced to leave two boys behind. Her angry former owner promptly sold them to an Alabama slaveholder. William Still would eventually be united with one of his enslaved brothers, Peter, who escaped to freedom in the North—a miraculous event that after the war inspired William to compile his history, hoping it would promote similar reunions.

The work of the Underground Railroad became the focal point of pro- and anti-slavery agitation after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Part of that year’s grand legislative compromise aimed at halting the slide toward civil war, the law required federal marshals to capture escaped slaves in Northern free states and denied jury trials to anyone imprisoned under the act. Abolitionists and supporters of slavery—each for their own reasons—tended to exaggerate the extent of the railroad’s operations, historian James McPherson observes, but there was no denying its effectiveness. As the decade progressed, the Fugitive Slave Act gave the work of the Underground Railroad new urgency.

Perhaps no one embodied the hunger for freedom more completely than John Henry Hill. A father and “young man of steady habits,” the 6-foot, 25-year-old carpenter was, in Still’s words, “an ardent lover of Liberty” who dramatically demonstrated his passion on January 1, 1853. After recovering from the shock of being told by his owner that he was to be sold at auction in Richmond, Hill arrived at the site of the public sale, where he mounted a desperate struggle to escape. Employing fists, feet and a knife, he turned away four or five would-be captors and bolted from the auction house. He hid from his baffled pursuers in the kitchen of a nearby merchant until he decided he wanted to go to Petersburg, Va., where his free wife and two children lived.

He stayed in Petersburg as long as he dared, leaving only when informed of a plot to capture him. Hill returned to his kitchen hideout in Richmond before learning that Still’s Vigilance Committee had arranged—at the considerable cost of $125—for him to have a private room on a steamship leaving Norfolk for Philadelphia. Four days after departing Richmond on foot, he arrived in Norfolk and boarded ship—more than nine months after escaping from the auction. “My Conductor was very much Excited,” Hill later wrote, “but I felt as Composed as I do at this moment, for I had started…that morning for Liberty or for Death providing myself with a Brace of Pistels.”

On October 4, Hill wrote Still to inform him that he had arrived safely in Toronto and found work. But other matters preoccupied him. “Mr. Still, I have been looking and looking for my friends for several days, but have not seen nor heard of them. I hope and trust in the Lord Almighty that all things are well with them. My dear sir I could feel so much better sattisfied if I could hear from my wife.”

But the Christmas season of 1853 brought good news. “It affords me a good deel of Pleasure to say that my wife and the Children have arrived safe in this City,” Hill wrote on December 29. Although she lost all her money in transit—$35—the family reunion proved deeply moving. “We saw each other once again after so long, an Abstance, you may know what sort of metting it was, joyful times of corst.”

During the next six years, Hill frequently wrote Still, reflecting on his experiences in Canada, the situation in the United States—and sometimes passing on sad family news. On September 14, 1854, Hill wrote of the death of his young son, Louis Henry, and his wife’s heartache at the boy’s passing. In another letter, Hill fretted about the fate of his uncle, Hezekiah, who went into hiding after his escape and ultimately fled to freedom after 13 months. Hill’s letters are replete with concern for escaped slaves and the volunteer “captains” of the Underground Railroad who risked imprisonment or death to assist runaways. Still acknowledged Hill’s spelling lapses but praised his correspondence as exemplifying the “strong love and attachment” freed slaves felt for relatives still in bondage.

Despite enormous difficulties, some families managed to escape to freedom intact.

Ann Maria Jackson, trapped in slavery in Delaware, made up her mind to flee north with her seven children when she learned alarming news of her owner’s plans. “This Fall he said he was going to take four of my oldest children and two other servants to Vicksburg,” she confided to Still. “I just happened to hear of this news in time. My master was wanting to keep me in the dark about taking them, for fear that something might happen.”

Those fears were well-founded. Upon learning of his planned departure for Mississippi, quick-thinking Jackson gathered her children and headed for Pennsylvania. The presence of slave-hunting spies along the state line complicated the family’s escape, but on November 21 a volunteer reported to Still that Jackson and her children, ranging in age from 3 to 16, were spotted across the state line in Chester County. From Pennsylvania, the family continued north into Canada. The 40 or so years Jackson had spent in slavery were at an end.

“I am happy to inform you that Mrs. Jackson and her interesting family of seven children arrived safe and in good health and spirits at my house in St. Catharines, on Saturday evening last,” Hiram Wilson wrote to Still from Canada on November 30. “With sincere pleasure I provided for them comfortable quarters till this morning, when they left for Toronto.”

Caroline Hammond’s family faced different challenges. Born in 1844, Hammond lived on the Anne Arundel County, Md., plantation of Thomas Davidson. Hammond’s mother was a house slave and her father, George Berry, “a free colored man of Annapolis.”

Davidson, she remembered, entertained on a lavish scale, and her mother was in charge of the meals. “Mrs. Davidson’s dishes were considered the finest, and to receive an invitation from the Davidsons meant that you would enjoy Maryland’s finest terrapin and chicken besides the best wine and champagne on the market.” Thomas Davidson, Hammond recalled, treated his slaves “with every consideration he could, with the exception of freeing them.”

Mrs. Davidson, however, was a different story. She “was hard on all the slaves, whenever she had the opportunity, driving them at full speed when working, giving different food of a coarser grade and not much of it.” Her hostility would soon evolve into something more sinister.

Hammond’s father had arranged with Thomas Davidson to buy his family’s freedom for $700 over the course of three years. Working as a carpenter, Berry made periodic partial payments to Thomas Davidson and was within $40 of completing the transaction when the slaveowner died in a hunting accident. Mrs. Davidson assumed control of the farm and the slaves, Hammond remembered—and refused to complete the transaction Berry had arranged with her late husband. As a result, “mother and I were to remain in slavery.”

The resourceful Berry, however, was undeterred. Hammond recalled that her father bribed the Anne Arundel sheriff for permits allowing him to travel to Baltimore with his wife and child. “On arriving in Baltimore, mother, father and I went to a white family on Ross Street—now Druid Hill Avenue, where we were sheltered by the occupants, who were ardent supporters of the Underground Railroad.”

The family’s escape had not gone unnoticed. Hammond remembered that $50 rewards were offered for their capture—one by Mrs. Davidson and one by the Anne Arundel sheriff, perhaps to protect himself from criticism for the role he played in aiding their escape in the first place. To flee Maryland, Hammond and her family clambered into “a large covered wagon” operated by a Mr. Coleman, who delivered merchandise to the towns between Baltimore and Hanover, Pa.

“Mother and father and I were concealed in a large wagon drawn by six horses,” Hammond recalled. “On our way to Pennsylvania we never alighted on the ground in any community or close to any settlement, fearful of being apprehended by people who were always looking for rewards.”

Once they were in Pennsylvania, life for Caroline and her family got much easier. Her mother and father settled in Scranton, worked for the same household and earned $27.50 a month. Hammond attended school at a Quaker mission.

When the war ended, her family returned to Baltimore. Hammond completed the seventh grade and, just like her mother, became a cook.

As she recounted her experiences as a slave in a 1938 interview with the Federal Writers’ Project, Hammond looked back on a life of 94 years with justified pride and satisfaction.

“I can see well, have an excellent appetite, but my grandchildren will let me eat only certain things that they say the doctor ordered that I should eat. On Christmas Day 49 children and grandchildren and some great-grandchildren gave me a Christmas dinner and $100 for Christmas,” she declared. “I am happy with all the comforts of a poor person not dependent on anyone else for tomorrow.”

Not surprisingly, freedom produced the same bliss and relief for a number of Underground Railroad passengers.

Hill’s correspondence with Still is suffused with the escaped slave’s profound joy in his new life. Even as he mourned the loss of his son, Hill reflected on his contentment. “It is true that I have to work very hard for comfort,” he acknowledged in a letter to Still in 1854, but freedom more than compensated for his grief and hardship.

“I am Happy, Happy.”

Robert B. Mitchell is the author of Skirmisher: The Life, Times and Political Career of James B. Weaver .

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

Western Writers of America Announces Its 2024 Wister Award Winner

Historian Quintard Taylor has devoted his career to retracing the black experience out West.

During Reconstruction Southern Planters Called on the US Army to Enforce an Old Status Quo

In a Louisiana parish, white elites sought military help to deny newly freed Blacks some of their rights.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The underground railroad.

- Diane Miller Diane Miller National Park Service Northeast Region, National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.974

- Published online: 19 October 2022

Africans and their descendants enslaved in the western hemisphere resisted their status in several ways. One of the most consequential methods was self-liberation. While many date the Underground Railroad as starting in the 1830s, when railroad terminology became common, enslaved people began escaping from the earliest colonial period. Allies assisted in journeys to freedom, but the Underground Railroad is centered around the enslaved people who resisted their status and asserted their humanity. Fugitives exhibited creativity, determination, courage, and fortitude in their bids for freedom. Together with their allies—white, Black, and Native American—they represented a grassroots resistance movement in which people united across racial, gender, religious, and class lines in hopes of promoting social change. While some participation was serendipitous and fleeting, the Underground Railroad operated through local and regional networks built on trusted circles of extended families and faith communities. These networks ebbed and flowed over time and space. At its root, the Underground Railroad was both a migration story and a resistance movement. African Americans were key participants in this work as self-liberators and as operators helping others to freedom. Their quest for freedom extended to all parts of what became the United States and internationally to Canada, Mexico, Caribbean nations, and beyond.

- Underground Railroad

- African American

- self-liberation

- Native American

Freedom Seeking in the Colonial and Revolutionary Periods

All of the European colonies established in North America allowed slavery, though the racialized system of African slavery took almost a century to evolve. To thrive in the Americas, colonizing powers needed to secure a labor force. Indentured servants and enslaved indigenous peoples proved to be a short-term solution. Increasingly Africans, both free and enslaved, became integral to the development of the colonies. Colonial powers all adopted slave codes, as early as the 16th and 17th centuries , to control the Black population and ensure a reliable labor force. A 1662 Virginia law, for example, declared that children born to Black women “shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.” 1 These laws limited Black rights and the paths to freedom. While a free Black population existed since the colonial era, by the 18th century most Africans and their descendants in what is now the United States were subject to hereditary enslavement as chattel. Slavery and the legal infrastructure that supported it were designed to dehumanize the enslaved. Through their resilience, enslaved Africans resisted this status from the beginning.

In 1526 , Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón brought several hundred Spanish and a large number of enslaved Africans from Hispaniola to settle near Sapelo Sound in Georgia. Disease and dissent doomed the effort. Emboldened by a mutiny among the Spanish, the enslaved Africans burned the compound while the indigenous Guale attacked the colony. Indeed, the first group of enslaved Africans brought to North America became the first to self-liberate. Settling among the Guale they became an early maroon community, forecasting a pattern of Native and African cooperation. 2 Future Spanish settlement in Florida, however, successfully established slavery. Spanish slave codes allowed for legal protections, church membership, and manumission. The Catholic Church provided sacraments of marriage and baptism; concerned for the souls of their enslaved members, the church discouraged breaking up enslaved families.

British slave codes, however, reduced the enslaved to chattel—movable personal property—and regulated them with harsh codes. Manumission was discouraged. As British planters developed rice cultivation in the Carolinas they imported skilled Africans, who soon learned the differences between the British and Spanish systems. Africans enslaved on the sea islands of the Carolina coast escaped south into Spanish Florida. As early as 1688 , the governor of South Carolina sent an envoy to St. Augustine to negotiate the return of fugitives. 3 In 1738 , Governor Don Manuel de Montiano enforced royal edicts of 1693 and 1733 that granted unconditional freedom to enslaved people escaping from the British southeast. In 1738 , a group of formerly enslaved and free people of color established the legally sanctioned town of Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose or Fort Mose, two miles north of St. Augustine. 4

Tobacco, the staple crop in the Chesapeake region, also required intensive labor performed by Africans, motivating resistance and escapes. Frustrated governors of Virginia and Maryland sought to negotiate with the Shawnees to return the runaways. Virginia governor Spotswood offered bounties of guns and blankets. Maryland’s governor sent delegations to the Shawnees to negotiate the return of fugitive slaves, offering silk stockings and woolen coats. 5 In October 1722 , the Maryland General Assembly discussed the matter of Indians being allowed to harbor runaway slaves, “as the Shuannoes at this Time do and protect them under the pretence of their having set such Slaves free. This Gentlemen we look upon as a Matter of Great Importance.” 6 At the confluence of the north and south branches of the Potomac River, near what is now Cumberland, Maryland, by the 1690s a band of Shawnees established a village, said to be led by King Opessa. The village was deserted before 1738 , when it was already shown on maps as “Shawno Ind. Fields deserted.” Through at least the 1720s, Shawnees living at King Opessa’s Town and neighboring sites offered refuge to fugitive slaves who had fled from their Virginia and Maryland masters. Repeated attempts failed to return any runaways.

In the vast territory that was added to the United States through the Louisiana Purchase, a power struggle among European nations led to control changing from France ( 1682 ) to Spain ( 1762 ), and back to France ( 1800 ) again before being sold in 1803 . Enslaved Africans played an important role in European efforts to establish a productive colony and control the region. The brutal and precarious conditions on the frontier gave rise to a fluid environment in which the enslaved population navigated. Plantations carved out of the wilderness were surrounded by swamps and waterways, proximately located to Indian settlements. Africans resisted their status by running away, often with assistance from nearby Native Americans. The cypress swamps provided a refuge for permanent maroon settlements comprised of escaped Africans. Extensive networks of secret passageways linked these maroon communities with plantations, and the free and enslaved populations regularly communicated with each other. At various times, this fluidity facilitated conspiracies and revolts. 7

The number of slaves who found refuge with Native American tribes during the colonial period must have been substantial, given the number of treaties that included clauses for their return. 8 In seven of eight treaties negotiated with Native American tribes from 1784 to 1786 , clauses were introduced for the return of “negroes and other property.” 9 By the time of the American Revolution, enslaved Africans had been self-liberating for 250 years. The Enlightenment ideals of freedom and liberty percolated in the colonies, giving rise to revolutionary fervor and the Declaration of Independence. This irony was understood by enslaved people, some of whom made their own break for freedom.

Societal disruption and the presence of competing loyalist and patriot factions opened opportunities for self-emancipation; some enslaved people exploited these opportunities to self-liberate. Military service was one of the means by which enslaved people attained freedom. Significantly, both the British and continental armies offered emancipation in return for service. Unable to field a sufficient number of white soldiers, for example, the Rhode Island Assembly in 1778 voted that every enslaved man who enlisted would be immediately discharged from service and absolutely free. 10 Eventually, every state except South Carolina and Georgia enlisted Blacks. In 1775 , Lord Dunsmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation offering freedom to any enslaved person who fought on the side of the British. Not only did this bring hundreds of soldiers to the British army, it also deprived the patriots of their labor. When the British army withdrew in 1783 , thousands of Black loyalists went with them. The British evacuated about three thousand to Nova Scotia, recording their names and descriptions in the Book of Negroes . Ultimately, most Black loyalists went to Britain, and some settled in the Caribbean.

The Freedom Seeker’s Journey

Of all the horrors of slavery, the cruelest was its effect on the spirit of the enslaved. Frederick Douglass, who escaped in 1838 and became a leading antislavery orator, described a period of his enslavement when he became a field hand hired to a notorious “slave breaker.” In his account, Douglass acknowledged that, after a few months, “I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished . . . the dark night of slavery closed in upon me.” 11 In a letter to Douglass published as a preface to the autobiography, abolitionist Wendell Phillips lauded him for describing the wretchedness of slavery by the “cruel and blighting death which gathers over his soul” rather than by the hunger, toil, and punishment he endured. 12 Freedom seekers had to overcome the soul-destroying nature of enslavement to self-liberate; they often also had to leave behind family and everyone they knew and loved. While a number of factors could precipitate self-liberation, it was the compelling need for freedom and self-determination that sustained freedom seekers. When asked by Underground Railroad activist Calvin Fairbank why he wanted his freedom, for example, Lewis Hayden replied “Because I’m a man.” 13

While most freedom seekers were young, single men, women and groups also made the journey. For women, the decision was complicated when they had young children. Harriet Tubman tried several times to rescue her sister, Rachel, who would not leave without her children. To her lasting regret, Tubman was never able to liberate Rachel, who died while enslaved. Another enslaved mother, Margaret Garner, attempted to flee with her husband and four of their children after two had been sold away. They made it across the Ohio River from Kentucky but were soon tracked down. Rather than see her children returned to a life of slavery, Margaret used a butcher knife to kill her two-year-old daughter. She tried to kill the other children but did not succeed. The Garners were returned to their enslaver, disquieting Ohio abolitionists, who did not want the precedent set allowing Kentucky enslavers to reclaim freedom seekers. Margaret’s desperate act illuminated the inhumanity of slavery.

Yet another mother, Ann Maria Jackson, succeeded in escaping from Delaware with seven of her children after another two were sold away. The grief of losing two of his children caused their father, a free Black man named John Jackson, to lose his sanity. Ann Maria, driven by a need to have autonomy to raise her children without fear of separation, decided that escaping was her best option. Bringing children on such a journey could easily compromise the safety of the group if they cried out or could not keep up. Jackson succeeded in escaping to Philadelphia as illustrated in Figure 1 . The consequences of being caught included being tortured, killed, maimed, or sold away.

Figure 1. Ann Maria Jackson arrives with her children at the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee.

On their journeys, freedom seekers had to be courageous, creative, adaptable, and resourceful. Most had to navigate their way to an indeterminate destination. Lucy Delaney recalled her mother using the North Star to guide her escape from Missouri. 14 John Brown used his knowledge of science to navigate using the moss found growing on trees. Concluding that the sun had dried the moss on the south side of the trees, he went in the direction “towards which the long, green moss pointed.” 15 Josiah Henson, shown in Figure 2 , described escaping slavery in 1830 with his wife and children. Thinking that they could find food from people along the way, Henson did not bring a supply. They found the Scioto trail but did not realize it cut through wilderness. Henson’s wife fainted from hunger but revived from the little morsel of food he had remaining. Their second day in the wilderness, the family came upon some Native Americans, who provided bountiful food and a comfortable place to sleep. 16 Knowing who to trust was one of the most important skills for freedom seekers on their journeys.

Figure 2. Josiah Henson, formerly enslaved author, abolitionist, and minister.

Free Black Communities and Vigilance Committees

The revolutionary fervor that compelled the United States to independence did not extend to the enslaved. While northern states enacted laws in the revolutionary period allowing for emancipation, in most states it took decades for slavery to actually end. Vermont abolished slavery by a constitutional amendment in 1777 , while slavery was ended in Massachusetts as a result of a legal decision. In New York and New Jersey, the largest slaveholding states in the north, however, slavery persisted until the mid- 19th century . 17 Nevertheless, a free Black population developed in the north, particularly in cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. These communities became key to the success of the Underground Railroad in the east. Freedom seekers could find refuge and employment amongst these populations, which were also a source of shelter, food, clothing, medical attention, legal aid, money, and transportation.

Vigilance committees formed among free Black communities and their white allies played a critical role in protecting freedom seekers. Beyond providing material and financial assistance, vigilance committees took direct action to rescue captured fugitives and kidnapped free Blacks who had been caught by slave catchers, empowered by the Fugitive Slave Laws of 1793 and 1850 . David Ruggles established the New York Vigilant Committee in 1835 . Initially focused on protecting free Blacks, particularly children, from kidnapping, the Committee evolved to provide assistance to fugitives. In 1838 , Ruggles notably sheltered Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Bailey) when he arrived in New York alone and without a plan. Ruggles summoned his fiancée, Anna Murray, to New York, where she married Douglass in Ruggles’s parlor. Ruggles gave them five dollars and sent them to another Black abolitionist in New Bedford. 18

Figure 3. Portrait of William Still

Inspired by Ruggles’s example, Robert Purvis convinced his associates to follow suit in 1837 when they formed the Vigilant Association of Philadelphia. It reorganized several times, with its last iteration formed in 1852 in response to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 . William Still (Figure 3 ) was appointed chair of the acting committee, which would assist individual cases, raise funds, and record their activities. 19 Still became the leader of the Underground Railroad network in Philadelphia. In 1872 , Still published The Underground Rail Road (Figure 4 ) based on the records of his work with the Vigilance Committee. Still’s work documents the stories of hundreds of freedom seekers, including Harriet Tubman and his long-lost brother, Peter Still. Further, he provided sketches of the network of white and Black abolitionists with whom he worked: Quakers Thomas Garrett and John Hunn; abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, J. Miller McKim, and Lewis Tappan; and African American activists William Whipper, Samuel Burris, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Harriet Tubman. In Boston, African American activist William Cooper Nell declared that “eternal vigilance is the price of liberty, and that they who would be free, themselves must strike the blow.” 20 The Boston Vigilance Committee posted broadsides (Figure 5 ) warning the community to remain alert to slave catchers. Lewis Hayden, who had previously escaped slavery in Kentucky and was one of the most active members of the Vigilance Committee, demonstrated this sentiment in October 1850 in one of the first tests of the new Fugitive Slave Law. William and Ellen Craft had escaped enslavement in Georgia using an elaborate disguise, with Ellen posing as a white male slaveholder traveling by train and ship with her enslaved servant, William. The ruse succeeded, and they made their way to Boston, where Hayden provided shelter. Slave catchers tracked the couple to Hayden’s house seeking their return. William Craft described the scene: “Lewis Hayden and I had a keg of gunpowder under his house in Phillips Street, with a fuse attached ready to light it should any attempt be made to capture us.” 21 After passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 , the Crafts emigrated to England to ensure their freedom

Figure 4. The Underground Railroad.

Figure 5. Fugitive Slave Law Warning Poster, 1851, Boston African American Historic Site.

Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

As the number of slave escapes escalated over the 1830s and 1840s, sectional tensions heightened. Southern slaveholding states pushed for enforcement of fugitive slave laws, while free states passed personal liberty laws to protect freedom seekers who had reached their borders. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 provided a mechanism to enforce the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution and return fugitives to their enslavers, though they may have been caught in free states. The law denied alleged slaves access to fair trials, due process of law, or the right to prove their freedom in court, in violation of several articles of the Bill of Rights. It also subverted the Constitution’s protection of the right to habeas corpus, which ensures that people arrested will be brought to court for a fair trial. In 1842 , the Supreme Court ruled in Prigg v Pennsylvania that states could refuse to allow their officials to enforce the fugitive slave law. A number of northern states based their refusal to assist in rendition of freedom seekers on this ruling. Used as a tool in the antislavery arsenal, Prigg v Pennsylvania led to calls for a new fugitive slave law. 22

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 supplemented the 1793 act by a series of amendments. Federal officials were appointed in each county to enforce the law by issuing arrest warrants and appointing deputies and posse comitatus for capturing fugitives. It required law enforcement officers to assist recapturing freedom seekers and punished anyone found assisting escapes. It also denied appeals once a certificate to remove a fugitive from a free state had been issued. Not even the Supreme Court could issue a writ of habeas corpus once a justice of the peace had issued a certificate of removal after an informal hearing. 23 Alleged fugitives were prohibited from testifying on their own behalf, and jury trials were forbidden. Additionally, if the magistrate ruled in favor of the enslaver, they received a ten-dollar fee, rather than the five-dollar fee they received if they decided for the freedom seeker. Anyone interfering in a rendition faced a thousand-dollar fine, as did federal marshals who failed to safeguard a fugitive. 24 This law inspired a spate of personal liberty laws in northern states designed to protect their Black populations from kidnapping and freedom seekers from rendition back to slavery. Many freedom seekers who had settled in the north made a subsequent journey to Canada, because they were no longer safe in the United States.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 set the stage for a series of dramatic cases and confrontations. On February 15, 1851 , Shadrach Minkins, who had escaped to Boston from Norfolk, was arrested by a federal marshal and taken to the courthouse. He became the first freedom seeker in New England captured under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 . 25 A group of Black men led by Lewis Hayden (Figure 6 ) rushed the courtroom and seized Minkins, shepherding him to safety. The authorities failed to pursue the rescue party. Minkins was hidden in the attic of a widow in the African American community of Beacon Hill, before Hayden got him out of town, and Minkins was able to make his way to safety in Quebec. In September 1851 , Maryland enslaver Edward Gorsuch attempted to seize a group of freedom seekers near Christiana, Pennsylvania. A predawn raiding party at the home of freedom seeker William Parker resulted in Gorsuch’s death and a severe wound to his son. Consequently, the federal government indicted forty-one men, including thirty-six Blacks and five whites, for treason. The trial took place at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, with Supreme Court Justice Robert Grier presiding and Congressman Thaddeus Stevens leading the defense. Castner Hanway, who refused to join the posse or to prevent the attack on the slave catchers, was the first tried. Justice Grier charged the jury that refusing to aid in a rendition did not constitute treason. The jury found Hanway not guilty, and the other indictments were eventually dropped. The Christiana Rebellion was not the most violent episode related to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 , but it garnered national attention due to the high-profile participants. 26

Figure 6. Lewis Hayden (1811–1889).

Another early attempt to enforce the 1850 law occurred in Syracuse in October 1851 , when a fugitive known as Jerry was arrested and placed in custody of US Deputy Marshal Henry Allen. A large crowd gathered at the courthouse attempting to rescue Jerry, who escaped to the streets but was recaptured. Organized by Gerrit Smith, Rev. Samuel J. May, and two Black ministers, Rev. Jermain Loguen and Rev. Samuel Ringgold Ward, a crowd attacked the jail where Jerry was held and succeeded in rescuing him and taking him to Canada. To further embarrass federal officials, deputy marshal Allen was indicted and tried for kidnapping. While he was not convicted, the trial provided a forum for abolitionists to attack slavery and the 1850 law. 27

Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law continued to stoke sectional tensions. One of the most famous and dramatic renditions occurred in 1854 when Anthony Burns was caught in Boston. This time, despite mass meetings and a failed rescue attempt where abolitionists broke down the courthouse door, the federal government returned to Burns slavery. Federal troops were deployed to guard the courthouse and prevent another rescue. They escorted Burns to Long Wharf while fifty thousand people lined the streets and abolitionists strung a coffin over the street with the word “Liberty” inscribed on it. The spectacle of federal troops escorting a freedom seeker back to slavery inspired many citizens to become abolitionists. 28 Massachusetts subsequently passed some of the strongest personal liberty laws in the country. Boston abolitionists ultimately raised funds to purchase Burns’s freedom.

Free states chafed at the federal enforcement of the fugitive slave law. The 1859 capture of Joshua Glover in Wisconsin led to a jurisdictional confrontation between state and federal authority. Glover had escaped slavery in Missouri and settled near Racine. His enslaver obtained a warrant under the Fugitive Slave Law, and Glover was jailed in Milwaukee due to concerns about a potential rescue in Racine. As might be expected, a large crowd gathered in protest, and a hundred men were sent to Milwaukee. They succeeded in rescuing Glover from jail, and he made it safely to Canada, where he died in 1888 . Sherman Booth, a newspaper editor who helped organize the protest, was arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act for aiding and abetting an escape. Federal prosecution of Booth led to defiance by Wisconsin courts over the issue of state habeas corpus jurisdiction versus federal judicial authority. The Wisconsin Supreme Court even defied the US Supreme Court by asking their clerk to make no return to a writ issued by the US Supreme Court. Chief Justice Roger Taney issued a unanimous opinion in the companion cases Abelman v Booth and United States v Booth that a state could not issue a writ of habeas corpus to remove a person from federal custody, establishing the supremacy of federal jurisdiction. 29 The assertion of federal over states’ rights incensed Wisconsin legislators and citizens, leading to discussion about secession from the union over federal enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law.

Geography of the Underground Railroad

Stereotypically, fugitives on the Underground Railroad sought freedom in Canada. While that is certainly true for many, the Underground Railroad was much more dynamic and complex. Self-liberators went in any direction where they could achieve freedom. Before the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 increased the risk of re-enslavement, many freedom seekers settled in states such as Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts, where slavery had been abolished during the late 1700s or early 1800s. When the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 proclaimed the territory north and west of the Ohio River to be free from slavery, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin became destinations for freedom seekers from the trans-Appalachian south.