COVID skewed journey-to -work census data. Here’s how city planners can make the best of it

Associate Professor, Director Australian Urban Observatory, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University

Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University

Professor of Urban Policy and Director, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University

Senior Research Fellow, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University

Disclosure statement

Melanie Davern receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and funded by RMIT University as a Vice Chancellor's Senior Research Fellow.

Alan Both receives funding from an NHMRC-UKRI (APP1192788) research grant.

RMIT University receives funding from a range of research and industry organisations for projects on which Jago Dodson works.

Tiebei (Terry) Li does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

RMIT University provides funding as a strategic partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Australian cities are slowly recovering from the COVID pandemic. Travel across cities is almost back to pre-pandemic levels. Google Mobility show only a 14% drop in travel to work across Victoria and 12% drop across New South Wales compared to pre-COVID results.

However, the disruption of COVID will reverberate through transport planning for years to come. The 2021 census – when people were asked about how they got to work – coincided with COVID lockdowns in our two biggest cities. The distortion of commuting patterns at that time creates problems for anyone who wishes to use these data.

Data on where people work, how they get to work and how far they travel represent a powerful tool for transport planners and policymakers. Transport has a critical influence on the liveability of cities , health , sustainability and quality of life .

So what can we do about these COVID-skewed transport data? In this article we propose some ideas to ensure the census results remain useful for city planning.

Why do the census responses matter?

The Australian Bureau of Statistics runs the census and has collected transport method and workplace data every five years since 1976 . In 2016, it improved these data to include distance travelled to work and commuting method .

In that year, 9.2 million commuters travelled an average distance of 16.5km to work. Of these people, 79% used a private vehicle, 14% took public transport and 5.2% cycled or walked. A further 500,000 people worked at home and 1 million employed persons did not go to work on census day.

The level of detail the census provides isn’t available with other methods. This is why the journey-to-work questions are so important.

But many of us were in lockdown in 2021

On census night, Australia’s two biggest cities, Melbourne and Sydney, were in lockdown , as were large regional cities across Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland (and the lockdown in Brisbane had ended only two days before ). People were asked : “How did the person get to work on Tuesday 10 August 2021?”

Planners and researchers are expecting some unusual results because of the lockdowns. We don’t know if people recorded their workplace as if the lockdown wasn’t in place, or treated their home as their workplace. While a higher-than-expected number of “worked at home” responses might signal the latter, we can’t know for certain.

The 2021 census data won’t provide a reliable record of “normal” commuting patterns, nor an accurate record of commuting changes over time. It’s not even clear if work attendance and commuting patterns will ever return to their pre-COVID state.

What can we do about the census data?

So the big question is how can decision-makers usefully work with the data to correct for the distortion of COVID lockdowns? We offer the following suggestions.

Look at cities that weren’t in lockdown

One option is to use the broad transport patterns from the least-locked-down parts of Australia, such as Adelaide or Perth. We can use their results and changes in transport mode over time to help estimate the results across other cities.

Link to previous census results

Another option would be to look at previous census results on journey to work for cities and try to match or predict what would have been expected in 2021 for different transport modes and distances. A benefit of this model is that previous results are available at local neighbourhood level and bring in the local influences of transport types and distances.

Another idea would be to look at the occupations that people list on their census forms, then match occupation types to transport modes used in previous census results.

Match to household travel survey data

Transport departments collect household-level travel data across a number of cities including Sydney and Melbourne to understand how far people travel and what transport modes they use. These surveys could be used to model area-based differences in journey-to-work patterns based on more up-to-date commuting results than older census data.

Investigate other travel datasets

The use of big data has come a long way since 2016. Today we have a number of other public and private travel data sets that could be used. These include Google Mobility results, traffic light counts, road sensors and Myki/Opal/go card travel data.

These data sets could be linked or modelled with census results to get a better estimate of results in locked-down areas.

Quarterly and annual COVID surveys could also help to understand how transport has changed throughout the pandemic.

Assess against other government data

Data linkage is another area that the Australian Bureau of Statistics has been working over the years. An example is the Multi-Agency Data Integration Project , which has been designed to help gain further insights from census data. The Australian Tax Office holds employment and work-related vehicle claims that might also be helpful to identify transport modes and travel demands by area.

Strict privacy rules apply to these data, but government agencies working together could lead to better commuting data for cities affected by lockdowns in 2021.

All these options have strengths and weaknesses. None is as good as the complete set of census data unaffected by lockdowns. However, they are worth considering when 2021 journey-to-work results are released on October 12.

Transport planners and researchers are ingenious. They will likely find ways to correct for the above problems to assess and understand transport patterns across Australian cities. Now is the time for discussion and ideas about these issues and the unusual census results to ensure transport planning is based on data that are both sound and up-to-date.

- Transport policy

- Transport planning

- Transport data

- Census 2021

- COVID lockdowns

- Better Cities

Communications and Events Officer

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Data Impact blog

The 2021 census, the pandemic, and journeys to work – part 2.

What might the future hold?

Ordinarily, the second most common mode of travel is about what people use other than driving cars, and can be useful for considering the potential and practicality of schemes to reduce car usage. This is complicated in the 2021 results by co-dominance of working from home. We could ask the question of how long lasting this apparent switch to working from home will be? Is it a pandemic response that will revert to previous levels over time, or does it represent a paradigmatic shift? It’s useful to remember the context.

At the time the country was in under pandemic restrictions, and many were working from home in a way that they had not done before. Yet at the same time, it is also possible that there was a preference for driving (amongst those with the option to do so) due to concerns about the safety (risk of exposure to Covid) of public transport. Public transport usage patterns may have changed, but use of masks and other mitigations have become much less common – a ‘fear of public transport’ narrative does not seem convincing for explaining current 2022 patterns of usage.

Are we seeing a genuine shift to working from home? Anecdotally, it would seem that this might be the case – many people are working at least part of the time from home. Yet it should be remembered that this is only an option for a limited set of people: some employers tackle more presenteeist approaches, and many occupations simply cannot be done from home.

This raises a question of how we might be able to tell whether this is a long-term shift. The census may not be the best instrument to explore this issue. A census, by its nature, asks a limited set of questions, often with a limited and fixed set of response categories. Typical forms only contain space to enter one set of details for an employer – it does not adapt well to record the circumstances of people with more than one job, especially if it is difficult to say which is the ‘main’ job. Similarly, only one transport mode can be entered.

The background to census limitations is that we may see a shift in whole or part away from traditional censuses and towards the use of admin data. However, the journey to work is a good example of a census theme that it is difficult to replicate in admin data. Even if there were good, consistent data about a person’s home, workplace, and employer), we would still be very unlikely to have any information about the mode of travel. Many people have expressed interest in the potential for use of mobile phone location data for observing people’s movement although some very significant hurdles would need to be overcome .

Effects of moving the census in Scotland

The postponement of the census in Scotland has also led to some unusual effects on the data.

Persons who travel to a workplace in Scotland from a residence in England, Wales or Northern Ireland will have been recorded in the census in 2021. Persons living in Scotland and working in England (or elsewhere in the UK) will have been recorded in the 2022 Census in Scotland. This temporal offset makes it impossible to produce simple UK level results.

This is also true of aggregate data: we can’t produce a comprehensive UK data set representing a fixed point in time – we would either have to model the Scottish results backwards, to produce estimates of the equivalent counts in 2021, or model forward the results in the rest of the UK to produce 2022 estimates.

Of course, this is quite possible – producing mid-year population estimates is part of statistical agencies’ normal work. The difference here is that we are looking at larger volumes of data with a wide variety of attributes, and furthermore that we would be modelling (whether forward or back) through a very volatile period. Here, we can return to the idea of commuting and migration flows – these were very strongly affected by the volatility of 2020-2022, and thus making estimates is difficult.

As with origin-destination data, unusual effects can occur in the aggregate data observations that are used as denominators in calculating flow rates. Someone who moved from England to Scotland between April 2021 and March 2022 would be recorded in both the 2021 Census in England and Wales, and the 2022 Census in Scotland. Their counterpart moving the opposite way would be recorded in neither.

How many people might be affected by this? It is hard to say, as the pandemic led to changes in work, and also to changes in where people were living. A constraint was that the housing market was not operating at its full capacity for parts of lockdown, and the markets in England and Wales and in Scotland operate under different regulatory environments.

However, the 2011 Special Workplace Statistics (SWS) and Special Migration Statistics (SMS) allow us to look at what was happening a decade ago. Both datasets are available through the UK Data Service ( https://wicid.ukdataservice.ac.uk/ )

Using the SMS, we can look at migration flows from specific origins to specific destinations. Grouping together by country, we find that in the year prior to the 2011 Census, 40,975 people moved to Scotland from the rest of the UK, and 42,554 moved from Scotland to the rest of the UK (these compare to around 490,000 moving within Scotland).

The totals in each direction are not hugely different, but it remains the case that the effects are opposite: those moving to Scotland would appear twice, and those moving from Scotland would not appear at all. However we can distinguish here between individuals, and their contribution to an aggregate total.

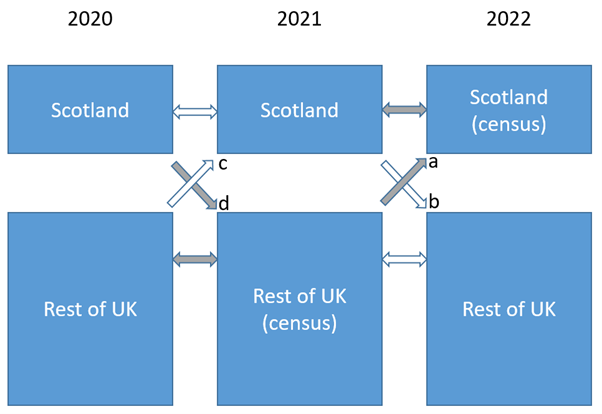

Figure 1 shows hypothetical flows between Scotland and the rest of the UK. Flows are indicated by arrows, and those arrows that are shaded grey are captured in the relevant census. The arrow marked ‘a’ represents those people moving from the rest of UK to Scotland in 2021-22 and (if they completed the form) captured in both censuses. The arrow marked ‘b’ represents those moving in the opposite direction and captured in neither. Does Scotland’s population show a false gain, through arrow ‘a’? No, because the ‘b’ flow has still taken place – people have left Scotland – and whilst they are not captured as individuals, their removal from the aggregate observation for Scotland has still occurred. Similarly, those in arrow ‘c’, who moved to Scotland in the year 2020-21 are not recorded (as migrants), but the change to aggregate stocks is still apparent.

Figure 1 – Flow components for migration between Scotland and the Rest of the UK 2020-21 and 2021-22

Does it matter at the individual level?

Of course, we would like all individuals to be reflected correctly in the data. In ‘normal’ times, we might assume that migrants have broadly similar characteristics: those who moved to Scotland in 2021-22 (arrow ‘a’) were similar to those who moved to Scotland in 2020-21 (arrow ‘c’), and so on. If this were the case, then we might think that the situation is not too bad – the similar sizes of flows means that stocks are not strongly affected, and the similarity of characteristics would that our aggregate observations would be consistent.

However, it is clear that we cannot assume similarity in characteristics of those moving at different stages in the pandemic. Some people remained in work (and those with jobs that could be conducted remotely may have had a broader choice in relocation destinations), whilst others were out of work or furloughed. Variations in the regulation of housing markets in both Scotland and in the rest of the UK will have affected the feasibility of moves, both for owner occupiers and for those renting.

We can also look at the SWS to examine flows of commuters across the border. In the 2011 Census there were around 29,000 people travelling for work from the rest of UK to Scotland, and 17,000 travelling from Scotland to the rest of the UK. This is perhaps more interesting than the migration data, given the bigger imbalance in the numbers.

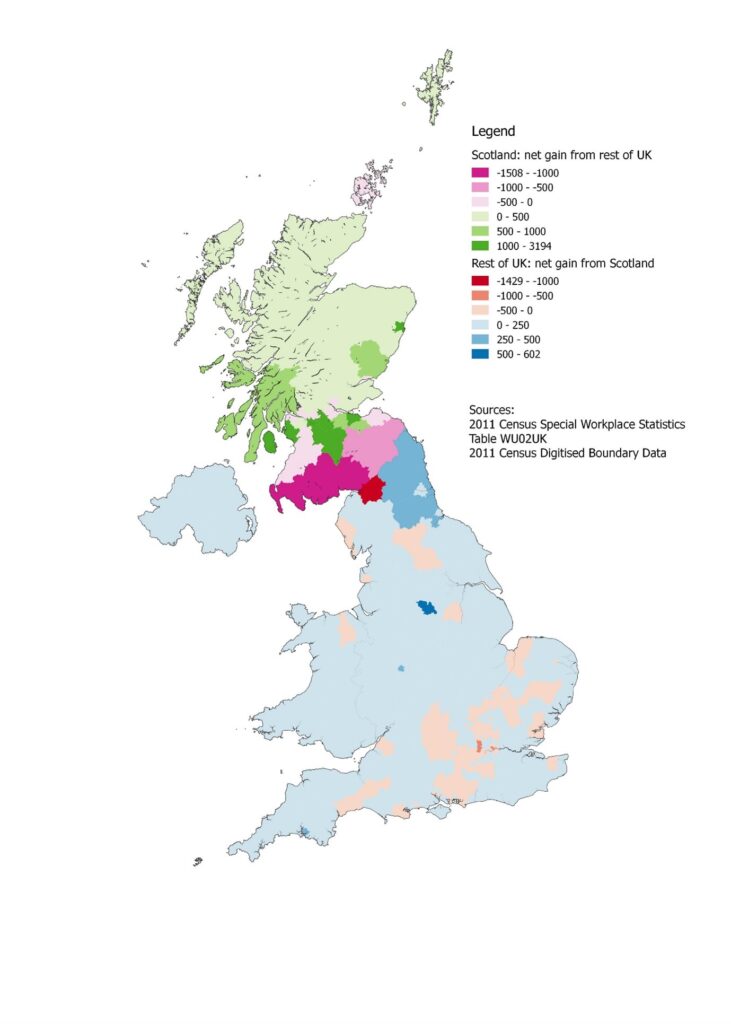

Figure 2 shows the pattern of cross-border commuting balances, using data from 2011. Unsurprisingly, the areas strongly affected are generally close to the border. For Scotland, we see gains in the central belt (that is, there were a larger number of people living in England and working in Edinburgh and Glasgow etc., than living in those locations and working in England). Elsewhere in Scotland we see a net loss of commuters in the Scottish Borders and Dumfries and Galloway areas.

Figure 2 – Net balance of journey to work data between Scotland and the Rest of the UK

Across England, we generally see small net balance, with stronger gains in Northumberland and County Durham. A notable gain is seen in Sheffield, and there are sporadic net losses in some parts of England – this perhaps reflecting weekly commuting patterns rather than daily ones.

Looking to the future

What then should we make of the delay in the census in Scotland?

Analysis of data from 2011 can only take us so far, as we know that this is unlikely to be greatly indicative of the movements taking place in the period 2020 to 2022. Comparisons that may be more interesting will be to look at the levels of working from home as reported in 2022 in Scotland.

According to the political narrative that we are now ‘post-pandemic’, Scotland has had an extra year for a potential return to ‘normality’. How many people in Scotland who might have said in 2021 that they were working from home had ‘returned to the office’ by the census in 2022? What are the patterns that we will see in this?

The 2021/22 journey to work data will help is to understand this process, both in Scotland and elsewhere. The migration data will help us to look at the characteristics of those moving (to and within Scotland) in 2021-22, and to compare them to those moving – albeit to different destinations – in 2020-21.

We will await these data with interest.

About the Author

Oliver Duke-Williams is an Associate Professor in Digital Information Studies at the UCL Department of Information Studies, and is deputy director of the Digital Humanities masters programmes there. He is also Census Service Director at the UK Data Service, and a senior advisor in the Centre for Longitudinal Study Information and User Support (CeLSIUS).

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Privacy Overview

Understanding Place of work data

Exploring the concepts and purpose of place of work data, to understand transport needs and commuting needs for the Australian public

People use Place of work ( POWP ) data for a variety of reasons, including when assessing public transport needs, measuring commuting distance and investigating local opportunities for work. The Census is the only data source with this specific information available Australia wide on a small area basis. Place of work information is only applicable to the 12 million people that were engaged in work in the week before the Census (10 August 2021).

POWP data provides information on where employed people aged 15 years or over worked in the week prior to the Census. POWP data is determined from the responses to the ‘Business name’ and ‘Workplace address’ questions on the Census form about the main place of work for the respondent in the last week. It is coded to geographic areas called Destination zones ( DZNs ). The data from POWP, Place of usual residence ( PURP ) and Method of travel to work ( MTWP ) can be cross classified to provide data on journey to work. This can be used to examine the movements of people to and from work, to analyse transport patterns and to assist in planning and development of transport systems.

Method of transport

MTWP provides information on the transport methods employed people used to get to work on the day of the Census. On the Census form, respondents could record multiple responses for method of transport. The majority of people however, only listed one transport method, with 2.0% of respondents listing multiple modes of transport. One exception was walking which is only included where walking was the sole method of transport to work, e.g. a person who caught the train then walked to work would be listed simply as catching the train to work.

The full listing of the combinations for multiple modes of transport used can be found in the 2021 Census dictionary . These can be re-grouped or recoded in different ways depending on the needs of the data user. When comparing MTWP totals against the number of total people employed, the number of people who did not go to work or worked at home on the day of the Census should be considered.

POWP and MTWP may look different in 2021 when compared to previous censuses due to the impact COVID-19 had on working patterns.

A number of regions across the country were in various stages of restrictions on and around Census Night, resulting in a greater number of people working from home. This is likely to have impacted responses to POWP. To see an approximate guide to the restrictions in place around this time, see COVID-19 restrictions by Local Government Areas .

In 2021, an instruction was added to the online form and the Census website to help people in areas affected by COVID-19 restrictions answer the Place of work question. People were instructed to list their employer's usual workplace address if they worked from home due to COVID-19 restrictions. This was to discourage people listing their home address as their workplace address.

Analysis of the proportion of people who listed the same Mesh Block for their usual residence and place of work showed only a slight increase from 2016 (7.3%) to 2021 (8.4%). Given so many people were experiencing COVID-19 restrictions on Census Night, this is a good indicator that in general, people completed the form as instructed.

Interpreting the data

The data items related to POWP have different time references. These should be considered when interpreting the data:

- Place of enumeration refers to the place where a person was counted on Census Night.

- Place of usual residence is where a person usually lives. It may or may not be the location where that person was counted on Census Night.

- Method of travel to work refers to how a person travelled to work on the day of the Census.

- Place of work refers to the address of the main job the respondent had in the week prior to the Census.

This difference in time frames can produce outliers in the data for a variety of reasons.

Example 1: Walked to Brisbane from the Gold Coast

A person spent the night before the Census in Brisbane with a friend and then walked to work in Brisbane city. After work she caught a train back to her parent's home on the Gold Coast (which she regarded as her usual place of residence) on the evening of Census Night, which was the location where she was enumerated.

Example 2: Caught a ferry to Alice Springs from Manly

A person mainly worked in Alice Springs during the week prior to the Census. However, the person could have:

- moved to Manly the day before the Census and taken a ferry to their new place of employment, or

- been a fly-in/fly-out worker who usually lived in Manly and was enumerated at home, but who temporarily visited the Sydney office the day of the Census, before heading back to Alice Springs for work.

Which to use: Place of enumeration or Place of usual residence?

Both Place of enumeration and Place of usual residence are valid ways of determining the origin of a journey, but they tell different stories. Some things to consider when looking at this data are:

- fly-in/fly-out workers and the different ways they may have reported themselves on the form

- enumeration shows an average day of the year (capturing visiting or holiday tendencies) whereas usual residence demonstrates more long-term trends

- usual residence is unlikely to reflect the movements of an average day, especially in inner city areas where numerous visitors may use transport and do not usually live in those specific areas.

Please see Comparing Place of enumeration with Place of usual residence for further information.

Troubleshooting

Why am i not getting any data.

It may be that no people resided in one particular area and worked in another area. This is common when cross-classifying POWP data with other variables such as occupation, industry and MTWP.

I am trying to get a reasonable comparison with other survey data

Be mindful of the geography you are using. If you are trying to compare Census data to other surveys, double check the definition of the geography for each.

My totals don't add up

Be careful when validating against employed totals. Figures may not add up for the following reasons:

- not including the Not stated category of POWP

- not including the Not stated category of MTWP

- if labour force is Not stated, then the POWP of that person is coded Not applicable

- if using 1996 data, Work destination study area ( DZSP ) must be used in conjunction with Work destination zone ( DZNP ) to fully define the DZNs

- the removal of additivity in the process of perturbation.

I am trying to compare Place of work data over different censuses

Place of work data has been produced since 1971, however the DZNs have been redefined after each Census to account for changes and growth within each state and territory. This means data is not comparable across censuses. Other reasons include:

- data was not available at DZNs level prior to 2011, except by customised data request

- changes to the question about Place of work, especially in the instructions for people with no place of work, and in coding persons to Not applicable and Not stated categories

- the 2016 Census was the first time the IFPOWP variable was available. This allows data users to identify not only if a DZN has been imputed, but precisely how much information the respondent had provided about their Place of work. Prior to 2016, Place of work was listed as Not stated for respondents who did not provide enough information.

- prior to 1986, all data was at the LGA level rather than Statistical Local Area (SLA) level. This is because the Australian Statistical Geography Classification was first introduced during the 1986 Census.

- prior to 2001 data on journey to work was available only for those people who lived and worked within study areas. Those who worked outside the study area (but were enumerated within it) were coded as 'Worked outside study area'. People enumerated outside study areas were not included in the data, regardless of where they worked.

I want to cross-tabulate Place of work with other geographies

A table cross-referencing SA2 of origin (Place of usual residence) by SA2 of destination (Place of work) for all of Australia should be avoided due to its size and difficulties in processing. A similar table could be attempted at a state level with additional cross-border SA2s added in. Areas that are smaller than an SA2 should not be cross-tabulated with Place of work, even at a state level.

SA1 and DZNs should only be attempted for specific areas of interest.

It is important to calculate cell counts before attempting a Place of work table as they can very easily exceed the maximum table size recommendation. The recommendation is that they are equal to or less than the target population (i.e. employed persons, or a subset thereof).

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By using this site, you agree to our cookie policy .

official census and labour market statistics

Dataset: ts058 - distance travelled to work, other information.

England and Wales

Contact details for this dataset

More data on nomis, about this dataset.

This dataset provides Census 2021 estimates that classify usual residents aged 16 years and over in employment the week before the census in England and Wales by the distance they travelled to work. The estimates are as at Census Day, 21 March 2021.

Census 2021 took place during a period of rapid change. We gave extra guidance to help people on furlough answer the census questions about work. However, we are unable to determine how furloughed people followed the guidance. Take care when using this data for planning purposes. Read more about specific quality considerations in our https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/methodologies/traveltoworkqualityinformationforcensus2021[Labour market quality information for Census 2021 methodology].

National Park data are created by plotting unique properties as identified by their Unique Property Reference Number or postcodes into National Park boundaries current at December 2022. This differs from the OA best fit methodology used for other geographic level data.

Protecting personal data

Sometimes we need to make changes to data if it is possible to identify individuals. This is known as statistical disclosure control. In Census 2021, we:

- Swapped records (targeted record swapping), for example, if a household was likely to be identified in datasets because it has unusual characteristics, we swapped the record with a similar one from a nearby small area. Very unusual households could be swapped with one in a nearby local authority.

- Added small changes to some counts (cell key perturbation), for example, we might change a count of four to a three or a five. This might make small differences between tables depending on how the data are broken down when we applied perturbation.

Explore in depth

The figures above are only a small sub-set of the data available in this dataset.

Download options

About the variables, distance travelled to work (11 categories).

Description: The distance, in kilometres, between a person's residential postcode and their workplace postcode measured in a straight line. A distance travelled of 0.1km indicates that the workplace postcode is the same as the residential postcode. Distances over 1200km are treated as invalid, and an imputed or estimated value is added.

"Work mainly at or from home" is made up of those that ticked either the 'Mainly work at or from home' box for the address of workplace question, or the "Work mainly at or from home" box for the method of travel to work question.

"Other" includes no fixed place of work, working on an offshore installation and working outside of the UK.

Distance is calculated as the straight line distance between the enumeration postcode and the workplace postcode.

Quality information: As Census 2021 was during a unique period of rapid change, take care when using this data for planning purposes.

Comparability with 2011: Not comparable. It is difficult to compare this variable with the 2011 Census because Census 2021 took place during a national lockdown. The government advice at the time was for people to work from home (if they can) and avoid public transport.

Only those who work at a workplace or depot gave their workplace address. This means that the number of people who answered this question is a significantly smaller proportion of the population than normal.

People who were on furlough (about 5.6 million), could have given details based on their patterns before or during the pandemic, or what they did during the census taking place, including Census Day.

- Total: All usual residents aged 16 years and over in employment the week before the census

- Less than 2km

- 2km to less than 5km

- 5km to less than 10km

- 10km to less than 20km

- 20km to less than 30km

- 30km to less than 40km

- 40km to less than 60km

- 60km and over

- Works mainly from home

- Works mainly at an offshore installation, in no fixed place, or outside the UK

Release calendar

Revisions and corrections.

Please wait...

- Skip to main content

- Skip to "About this site"

Language selection

- Français

- Search and menus

2016 Census topic: Journey to work

Release date: November 29, 2017 Updated on: December 2, 2019

The 2016 Census of Population Program offers a wide range of analysis, data, reference and geographical information according to topics (subjects) that paint a portrait of Canada and its population.

Data products

- Census Profile, 2016 Census

- Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census

- Data tables, 2016 Census – Journey to work

- Census Program Data Viewer, 2016 Census

- Census Profile Standard Error Supplement, Canada, provinces, territories, census divisions (CDs) and aggregate dissemination areas (ADAs), 2016 Census

Analytical products

- The Daily as reported on November 29, 2017

- Commuters using sustainable transportation in census metropolitan areas

- Results from the 2016 Census: Commuting within Canada's largest cities

- Results from the 2016 Census: Long commutes to work by car

- Commuting in Canada's three largest cities

- Journey to work, 2016 Census of Population

Reference material

- 2016 Census Dictionary: Journey to work

- Journey to work Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2016

- Release and Concepts Overview, 2016 Census of Population: Journey to work

- Guide to the Census of Population, 2016

Geography

Key indicators, selected geographical area: canada.

% using public transit to get to work, 2016

Source: 2016 Census of Population

Average commuting duration, in minutes, 2016

Need journey to work information from previous censuses?

- 2011 Census Program Education and labour (Archived)

- 2006 Census Place of work and commuting to work (Archived)

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Most work is new work, long-term study of U.S. census data shows

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

This is part 1 of a two-part MIT News feature examining new job creation in the U.S. since 1940, based on new research from Ford Professor of Economics David Autor. Part 2 is available here .

In 1900, Orville and Wilbur Wright listed their occupations as “Merchant, bicycle” on the U.S. census form. Three years later, they made their famous first airplane flight in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. So, on the next U.S. census, in 1910, the brothers each called themselves “Inventor, aeroplane.” There weren’t too many of those around at the time, however, and it wasn’t until 1950 that “Airplane designer” became a recognized census category.

Distinctive as their case may be, the story of the Wright brothers tells us something important about employment in the U.S. today. Most work in the U.S. is new work, as U.S. census forms reveal. That is, a majority of jobs are in occupations that have only emerged widely since 1940, according to a major new study of U.S. jobs led by MIT economist David Autor.

“We estimate that about six out of 10 jobs people are doing at present didn’t exist in 1940,” says Autor, co-author of a newly published paper detailing the results. “A lot of the things that we do today, no one was doing at that point. Most contemporary jobs require expertise that didn’t exist back then, and was not relevant at that time.”

This finding, covering the period 1940 to 2018, yields some larger implications. For one thing, many new jobs are created by technology. But not all: Some come from consumer demand, such as health care services jobs for an aging population.

On another front, the research shows a notable divide in recent new-job creation: During the first 40 years of the 1940-2018 period, many new jobs were middle-class manufacturing and clerical jobs, but in the last 40 years, new job creation often involves either highly paid professional work or lower-wage service work.

Finally, the study brings novel data to a tricky question: To what extent does technology create new jobs, and to what extent does it replace jobs?

The paper, “ New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940-2018 ,” appears in the Quarterly Journal of Economics . The co-authors are Autor, the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT; Caroline Chin, a PhD student in economics at MIT; Anna Salomons, a professor in the School of Economics at Utrecht University; and Bryan Seegmiller SM ’20, PhD ’22, an assistant professor at the Kellogg School of Northwestern University.

“This is the hardest, most in-depth project I’ve ever done in my research career,” Autor adds. “I feel we’ve made progress on things we didn’t know we could make progress on.”

“Technician, fingernail”

To conduct the study, the scholars dug deeply into government data about jobs and patents, using natural language processing techniques that identified related descriptions in patent and census data to link innovations and subsequent job creation. The U.S. Census Bureau tracks the emerging job descriptions that respondents provide — like the ones the Wright brothers wrote down. Each decade’s jobs index lists about 35,000 occupations and 15,000 specialized variants of them.

Many new occupations are straightforwardly the result of new technologies creating new forms of work. For instance, “Engineers of computer applications” was first codified in 1970, “Circuit layout designers” in 1990, and “Solar photovoltaic electrician” made its debut in 2018.

“Many, many forms of expertise are really specific to a technology or a service,” Autor says. “This is quantitatively a big deal.”

He adds: “When we rebuild the electrical grid, we’re going to create new occupations — not just electricians, but the solar equivalent, i.e., solar electricians. Eventually that becomes a specialty. The first objective of our study is to measure [this kind of process]; the second is to show what it responds to and how it occurs; and the third is to show what effect automation has on employment.”

On the second point, however, innovations are not the only way new jobs emerge. The wants and needs of consumers also generate new vocations. As the paper notes, “Tattooers” became a U.S. census job category in 1950, “Hypnotherapists” was codified in 1980, and “Conference planners” in 1990. Also, the date of U.S. Census Bureau codification is not the first time anyone worked in those roles; it is the point at which enough people had those jobs that the bureau recognized the work as a substantial employment category. For instance, “Technician, fingernail” became a category in 2000.

“It’s not just technology that creates new work, it’s new demand,” Autor says. An aging population of baby boomers may be creating new roles for personal health care aides that are only now emerging as plausible job categories.

All told, among “professionals,” essentially specialized white-collar workers, about 74 percent of jobs in the area have been created since 1940. In the category of “health services” — the personal service side of health care, including general health aides, occupational therapy aides, and more — about 85 percent of jobs have emerged in the same time. By contrast, in the realm of manufacturing, that figure is just 46 percent.

Differences by degree

The fact that some areas of employment feature relatively more new jobs than others is one of the major features of the U.S. jobs landscape over the last 80 years. And one of the most striking things about that time period, in terms of jobs, is that it consists of two fairly distinct 40-year periods.

In the first 40 years, from 1940 to about 1980, the U.S. became a singular postwar manufacturing powerhouse, production jobs grew, and middle-income clerical and other office jobs grew up around those industries.

But in the last four decades, manufacturing started receding in the U.S., and automation started eliminating clerical work. From 1980 to the present, there have been two major tracks for new jobs: high-end and specialized professional work, and lower-paying service-sector jobs, of many types. As the authors write in the paper, the U.S. has seen an “overall polarization of occupational structure.”

That corresponds with levels of education. The study finds that employees with at least some college experience are about 25 percent more likely to be working in new occupations than those who possess less than a high school diploma.

“The real concern is for whom the new work has been created,” Autor says. “In the first period, from 1940 to 1980, there’s a lot of work being created for people without college degrees, a lot of clerical work and production work, middle-skill work. In the latter period, it’s bifurcated, with new work for college graduates being more and more in the professions, and new work for noncollege graduates being more and more in services.”

Still, Autor adds, “This could change a lot. We’re in a period of potentially consequential technology transition.”

At the moment, it remains unclear how, and to what extent, evolving technologies such as artificial intelligence will affect the workplace. However, this is also a major issue addressed in the current research study: How much does new technology augment employment, by creating new work and viable jobs, and how much does new technology replace existing jobs, through automation? In their paper, Autor and his colleagues have produced new findings on that topic, which are outlined in part 2 of this MIT News series.

Support for the research was provided, in part, by the Carnegie Corporation; Google; Instituut Gak; the MIT Work of the Future Task Force; Schmidt Futures; the Smith Richardson Foundation; and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- David Autor

- Department of Economics

Related Topics

- Labor and jobs

- Manufacturing

- Innovation and Entrepreneurship (I&E)

- Artificial intelligence

- History of science

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

Related Articles

Does technology help or hurt employment?

Report outlines route toward better jobs, wider prosperity

The urban job escalator has stopped moving

Trading places

Polarized labor market leaving more employees in service jobs

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

Drinking from a firehose — on stage

Read full story →

Researchers 3D print key components for a point-of-care mass spectrometer

Unlocking new science with devices that control electric power

A new computational technique could make it easier to engineer useful proteins

MIT researchers discover “neutronic molecules”

Characterizing social networks

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Regional and local government

- Northern Ireland

Census 2021: Flexible Table Builder update - minor changes and enhancements

An online Table Builder that will allow users to build Census 2021 tables for Northern Ireland on-demand. This update will include data for a number of census topics (approximated social grade, former occupation, and former industry), new census Data Zone geography aggregations (Urban Status and 2011 Travel to Work Areas), and updates to some additional classifications.

Applies to Northern Ireland

https://build.nisra.gov.uk/en/

Official statistics are produced impartially and free from political influence.

Is this page useful?

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. We’ll send you a link to a feedback form. It will take only 2 minutes to fill in. Don’t worry we won’t send you spam or share your email address with anyone.

The Federal Register

The daily journal of the united states government, request access.

Due to aggressive automated scraping of FederalRegister.gov and eCFR.gov, programmatic access to these sites is limited to access to our extensive developer APIs.

If you are human user receiving this message, we can add your IP address to a set of IPs that can access FederalRegister.gov & eCFR.gov; complete the CAPTCHA (bot test) below and click "Request Access". This process will be necessary for each IP address you wish to access the site from, requests are valid for approximately one quarter (three months) after which the process may need to be repeated.

An official website of the United States government.

If you want to request a wider IP range, first request access for your current IP, and then use the "Site Feedback" button found in the lower left-hand side to make the request.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Access demographic, economic and population data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Explore census data with visualizations and view tutorials. ... Commuting (Journey to Work) Commuting data includes where people work (including work from home), when their trip starts, how they get there, and how long it takes. ... Home-Based Workers: 2019-2021 ...

APRIL 6, 2023 — The U.S. Census Bureau today released a report describing trends in working from home before and after the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States in March 2020.The report, Home-Based Workers and the COVID-19 Pandemic, uses 2019 and 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year estimates to compare teleworking sociodemographic, geographic and occupational patterns the year ...

Journey to work. Since 1976, the Census has collected data on the modes of transport Australians use to commute to work. Employed people aged 15 years and over could record up to three methods of travel they used to get to work on the day of the Census. The 2021 Census was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 2021 census - when people were asked about how they got to work - coincided with COVID lockdowns in our two biggest cities. The distortion of commuting patterns at that time creates ...

Virtual 2021 Census data seminar - Journey to workIncludes information on:1. 2021 Census data insights.2. What Census data tools are available.3. Using Journ...

The following interactive map illustrates how employed Australians travelled to work on Census day in 2011, 2016 and 2021 by Statistical Area Level 3. Further analysis on the modes of transport Australians used to commute to work, and the type of work they did, can be found in Australia's journey to work. The Census of Population and Housing collects data on what modes of transport employed ...

Commuting patterns and characteristics are crucial to planning for improvements to road and highway infrastructure, developing transportation plans and services, and understanding where people are traveling in the course of a normal day. The 1960 Census was the first to ask about how people get to work. In 1970, the Census added a question ...

The census date (March 21, 2021) occurred during the pandemic, and thus many peoples' work was affected. This date was during a phase when a 'stay at home' order was in force. The census aimed to gather data about what people were doing at that time, rather than what they may have been doing had the pandemic not occurred.

People were asked to select one mode of transport that they used for the longest part, by distance, of their usual journey to work. In total, there were an estimated 8.7 million people in England and Wales who worked mainly at, or from, their homes. ... Census 2021 travel to work data use the 2001 travel to work specification, which is a method ...

About this dataset. This dataset provides Census 2021 estimates that classify usual residents in England and Wales by their method used to travel to work (2001 specification). The estimates are as at Census Day, 21 March 2021. Census 2021 took place during a period of rapid change. We gave extra guidance to help people on furlough answer the ...

Each year, the American Community Survey publishes statistics related to commuting in the United States. The charts below show trends for key commuting estimates. These graphics are sourced from Table S0801, available at data.census.gov. The mean one-way travel time in 2021 was 25.6 minutes, lower than 27.6 minutes in 2019.

The 2021/22 journey to work data will help is to understand this process, both in Scotland and elsewhere. The migration data will help us to look at the characteristics of those moving (to and within Scotland) in 2021-22, and to compare them to those moving - albeit to different destinations - in 2020-21. We will await these data with interest.

Place of work information is only applicable to the 12 million people that were engaged in work in the week before the Census (10 August 2021). ... This is because the Australian Statistical Geography Classification was first introduced during the 1986 Census. prior to 2001 data on journey to work was available only for those people who lived ...

The 2021 Census of Population underwent a thorough data quality assessment. The different certification activities conducted to evaluate the quality of the 2021 Census data are described in Chapter 9 of the Guide to the Census of Population, 2021, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-304-X. The data quality assessment was conducted in addition to ...

In preparation for the 2021 Census, Statistics Canada conducted a content consultation from fall 2017 to spring 2018 using an online questionnaire and face-to-face discussions. Consultation respondents and federal stakeholders suggested that the census questionnaire provide more information on labour and journey to work .

3 August 2023. These plans detail the analysis we aim to publish on the topic of travel to work in the first year of the Census 2021 analysis programme, and the proposals we are considering publishing in following years. We will provide updates to these plans after user feedback and further research and testing of the data.

1. Main points. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) collected Census 2021 responses during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, a period of unparalleled and rapid change; the national lockdown, associated guidance and furlough measures will have affected the travel to work topic. We provided extra guidance to respondents affected by the ...

History of commuting / journey to work questions. The question about how people get to work originated with the 1960 Census. The question about where a person worked originated with the 1970 Census The question about how long it took people to get to work originated with the 1980 Census and the time of departure question originated with the ...

This dataset provides Census 2021 estimates that classify usual residents aged 16 years and over in employment the week before the census in England and Wales by the distance they travelled to work. The estimates are as at Census Day, 21 March 2021. Census 2021 took place during a period of rapid change. We gave extra guidance to help people on ...

2016 Census topic: Journey to work. Release date: November 29, 2017 Updated on: December 2, 2019. The 2016 Census of Population Program offers a wide range of analysis, data, reference and geographical information according to topics (subjects) that paint a portrait of Canada and its population.

Also, the date of U.S. Census Bureau codification is not the first time anyone worked in those roles; it is the point at which enough people had those jobs that the bureau recognized the work as a substantial employment category. For instance, "Technician, fingernail" became a category in 2000.

MARCH 18, 2021 — A new report released today by the U.S. Census Bureau shows the average one-way commute in the United States increased to a new high of 27.6 minutes in 2019.The Travel Time to Work in the United States: 2019 report summarizes trends in travel time among U.S. workers between 2006 and 2019 using single-year data from the American Community Survey (ACS).

An online Table Builder that will allow users to build Census 2021 tables for Northern Ireland on-demand. This update will include data for a number of census topics (approximated social grade ...

According to OMB, the delineations reflect the 2020 Standards for Delineating Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) (the "2020 Standards"), which appeared in the Federal Register (86 FR 37770 through 37778) on July 16, 2021, and application of those standards to Census Bureau population and journey-to-work data (for example, 2020 Decennial ...

Almost 140 million people in the United States routinely commuted to work in 2022, and more than 20 million worked from home. Among U.S. workers, 15.2% worked from home in 2022, down from almost 17.9% in 2021 but still far higher than the 5.7% that worked from home before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019.